Abstract

Chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis-caused bone destruction, results from an increase of bone-resorbing osteoclasts (OCs) induced by inflammation. However, the detailed mechanisms underlying this disorder remain unclear. We herein investigated that the effect of urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) on inflammatory osteoclastogenesis induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which is a potent stimulator of bone resorption in inflammatory diseases. We found that the uPA deficiency promoted inflammatory osteoclastogenesis and bone loss induced by LPS. We also showed that LPS induced the expression of uPA, and the uPA treatment attenuated the LPS-induced inflammatory osteoclastogenesis of RAW264.7 mouse monocyte/macrophage lineage cells. Additionally, we showed that the uPA-attenuated inflammatory osteoclastgenesis is associated with the activation of plasmin/protease-activated receptor (PAR)-1 axis by uPA. Moreover, we examined the mechanism underlying the effect of uPA on inflammatory osteoclastogenesis, and found that uPA/plasmin/PAR-1 activated the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway through Ca2+/calmodulin dependent protein kinase kinase (CaMKK) activation, and attenuated inflammatory osteoclastogenesis by inactivation of NF-κB in RAW264.7 cells. These data suggest that uPA attenuated inflammatory osteoclastogenesis through the plasmin/PAR-1/Ca2+/CaMKK/AMPK axis. Our findings may provide a novel therapeutic approach to bone loss caused by inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: uPA, plasmin, AMPK, osteoclasts, inflammation

Introduction

Chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis frequently cause the bone destruction. Soluble factors including lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-1 regulate the progression of bone loss by resulting in the differentiation and activation of bone-resorbing osteoclasts (OCs) 1-3. Additionally, OC function is regulated by the receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK) and its ligand (RANKL), and the NF-κB signaling activated by RANKL has proven to be absolutely required for OCs development 4, 5. The NF-κB signaling is also activated by LPS, TNF-α, and IL-1 6-8 and the specific inhibition of NF-κB markedly blocked inflammatory bone destruction 9. However, the mechanism of inflammation-induced bone loss remains poorly understood.

It has been known that urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) is associated with the inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, periodontitis, cancer, and fibrosis, and modulates the development of protective immunity 10-13. uPA is a serine protease that activates plasminogen (Plg) into plasmin, and is considered to be one of the mediators of fibrinolysis 14. uPA-generated plasmin not only degrade fibrin and any extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins but also activate matrix metalloproteinases, growth factors and protease-activated receptor (PAR)-1 15, 16. Recently, it has been reported that PAR-1 can activate adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) through Ca2+/calmodulin dependent protein kinase kinase (CaMKK) 17, and the AMPK acts as a negative regulator during OC differentiation 18. However, the role of uPA, plasmin, PAR-1, and AMPK on inflammatory osteoclastogenesis remain poorly understood. We herein first report that uPA attenuated LPS-induced inflammatory osteoclastogenesis through the plasmin/PAR-1/Ca2+/CaMKK/AMPK axis.

Material and Methods

The animal experiments in this study were approved by the Animal Research Committee of Doshisha Women's College of Liberal Arts (Approval ID: Y13-018, Y14-020).

Animals

The uPA deficient (uPA-/-) mice were kindly provided by Prof. D Collen (University of Leuven, Belgium). Wild type, uPA-/-mice littermates were housed in groups of two to five in filter-top cages with a fixed 12 hours light, 12 hours dark cycle.

Bone destruction by the administration of LPS in mice

25 mg/kg LPS was administered subcutaneously into the shaved back of the male mice. The administration was carried out weekly for up to 4 weeks.

Bone histology

Bone histomorphometry of femurs in male uPA+/+ and uPA-/- mice were performed. Each femur was removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 days, and then demineralized with 10% EDTA for 14 days before embedding in paraffin. Paraffin-embedded tissue was serially sectioned at 4-7-μm distances. Then, the sections were stained with TRAP by using TRAP kit (Sigma- Aldrich, MO, USA).

For the quantitative evaluation of the intensity of TRAP-staining in decalcified sections of femurs from the uPA+/+ and uPA-/- mice, the TRAP-stained images obtained from separate fields on the specimens were analyzed by using ImageJ 1.43u.

Measurement of bone mineral density

Bone mineral density (BMD) was measured as previously described 19. The BMD of femurs from mice at the indicated time was evaluated by using peripheral quantitative computed tomography with a fixed x-ray fan beam of 50-μm spot size, at 1 mA and 50 kVp (LaTheta LCT-100S; Aloka, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell culture

Bone marrow cells were obtained as previously described 19. Bone marrow cells, RAW264.7 mouse monocyte/macrophage lineage cells were maintained in α-MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37℃ in a humidified atmosphere of 5 % CO2 / 95 % air.

OC differentiation assay

Mouse bone marrow cells or RAW264.7 cells were cultured for 3 days with LPS (1 μg/ml) and M-CSF (100 ng/ml) in 48-well plates. Cells were then fixed and stained for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP; a marker enzyme of OCs) as described 19. TRAP-positive multinucleated cells containing three or more nuclei were counted as OCs, under microscopic examination.

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted as previously described 19. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA by using the High Fidelity RT-PCR Kit (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on the IQ5 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) with SYBR Green technology on cDNA generated from the reverse transcription of purified RNA. The 2 step PCR reactions were performed as 92℃ for 1 sec and 60℃ for 10 sec. Plg, and uPA mRNA expression were normalized against GAPDH mRNA expression using the comparative cycle threshold method. We used the following primer sequence: Plg, 5'-TGGCTACATAAGCACACAAG-3' and 5'-ACATTCTGACAGATACACTC-3'; uPA, 5'-CGCCTGCTGTCCTTCAGAAAC-3' and 5'-CAA GATGAGCTGCTCCACCTC-3'; GAPDH, 5'-TGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTGA-3' and 5'-TTGCTGTTGAAGTCGCAGGAG -3'.

Western blot analysis

We studied a Western blot analysis as previously described 20. We detected NFATc1, phospho-AMPK, AMPK, IκBα, or GAPDH by incubation with anti-NFATc1 antibody, anti-phospho-AMPK antibody, anti-AMPK antibody, anti-IκBα antibody, or anti-GAPDH antibody followed incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody to rabbit IgG (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden).

Dual luciferase reporter assay

pGL4.32 (luc2P/NF-κB/Hygro) vector contains five copies of NF-κB response element (NF-κB-RE) that derives transcription of the luciferase reporter gene luc2P (Promega, WI, USA). RAW264.7 cells were co-transfected with pGL4.32 (luc2P/NF-κB/Hygro) vector and the internal control vector pGL4.74 (hRluc/TK) using the Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. At 24 hours post-transfection, the cells were stimulated with described reagents, and then assayed for luciferase activity using the Dual-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean±SEM. The significance of the effect of each treatment (P <0.05) was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the least significant difference test.

Results

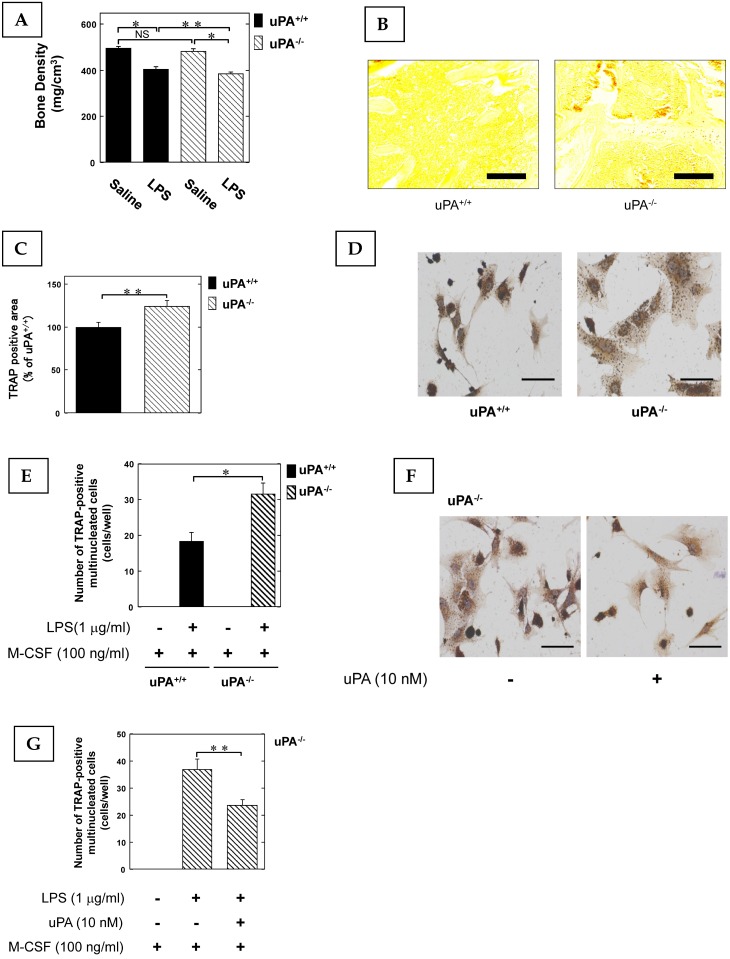

The effect of uPA and uPAR deficiency in inflammatory osteoclastogenesis and bone destruction

To clarify the role of the uPA in inflammatory osteoclastogenesis and bone destruction, we examined the bone mineral density (BMD) in the femurs of uPA deficient mice following the administration of LPS, which not only induces inflammation but also osteoclastic bone resorption 6. The LPS-induced decrease of BMD in the femurs of uPA-/- mice was significantly more potent than in uPA+/+ mice (Fig. 1A). Next, we examined the amount of OCs in the femurs of mice stimulated with LPS using TRAP-staining. The TRAP-positive area in the femurs of uPA-/- mice was significantly larger than that of uPA+/+ mice (Fig. 1B, C). Moreover, we examined the pre-OCs population in bone marrow-derived cells from mice following stimulation with LPS and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF). The TRAP-positive cell number in the bone marrow-derived cells from uPA-/- mice was significantly higher than in uPA+/+ mice (Fig. 1D, E). Additionally, uPA treatment on the bone marrow-derived cells from uPA-/- mice attenuated the increase of TRAP-positive cell number induced by LPS (Fig. 1F, G).

Figure 1.

The uPA deficiency promotes inflammatory osteoclastogenesis and bone destruction. 25 mg/kg LPS was administered subcutaneously into the shaved back of the male mice. The administration was carried out weekly for up to 4 weeks. (A) The BMD in the femurs of the LPS-administered male uPA+/+ and uPA-/- mice was obtained from pQCT measurement (saline or LPS-administered uPA+/+ mice, n=9; saline or LPS-administered uPA-/- mice, n=8). (B) The TRAP-staining of femurs in the LPS-administered male uPA+/+ and uPA-/- mice. (C) The intensity of TRAP-staining on the decalcified sections in the LPS-administered male uPA+/+ and uPA-/- mice was quantitatively evaluated as described in the Materials and Methods (n=6). (D) Bone marrow-derived cells from the uPA+/+ and uPA-/- mice were cultured for 3 days in the presence of LPS (1 μg/ml) and M-CSF (100 ng/ml). Then, TRAP-staining was performed to detect mature OCs. (E) Mature OCs were identified as multinucleated TRAP-positive cells (n=4). (F) Bone marrow-derived cells from the uPA-/- mice were cultured for 3 days with LPS (1 μg/ml), M-CSF (100 ng/ml), and with or without uPA (10 nM). Then, TRAP-staining was performed to detect mature OCs. (G) Mature OCs in the uPA-/- mice were identified as multinucleated TRAP-positive cells (n=3). The data represent the mean ± SEM. *, P<0.01; **, P<0.05; NS, not significant. Scale bar = 200 μm.

LPS induced uPA and Plg mRNA expression in pre-OCs RAW264.7 cells

We examined the uPA and Plg mRNA expression levels in pre-OCs RAW264.7 cells stimulated by LPS (1 μg/ml). LPS induced both uPA and Plg expression, the maximum effect of LPS was observed at 2 days after stimulation (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, we examined the mechanism of LPS-induced uPA expression by using the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) specific inhibitor (PD98059) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) specific inhibitor (SP600125). Both PD98059 and SP600125 attenuated LPS-induced uPA expression (Fig. 2B). This data suggest that the LPS-induced uPA expression is associated with the MEK and JNK pathways.

Figure 2.

LPS induced uPA and Plg mRNA expression in pre-OCs RAW264.7 cells. (A) RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS for the indicated periods. The uPA, and Plg mRNA expression in RAW264.7 cells stimulated by LPS was evaluated by qRT-PCR (n=3). (B) RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with PD98059 (30 μM) or SB203580 (30 μM) for 30 minutes and then stimulated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 48 hours. The uPA mRNA expression in RAW264.7 cells stimulated by LPS was evaluated by qRT-PCR (n=3). The data represent the mean ± SEM. *, P<0.01; **, P<0.05.

uPA attenuated inflammatory osteoclastogenesis through plasmin/PAR-1

We examined the effect of uPA on inflammatory osteoclastogenesis induced by LPS stimulation. uPA attenuated the increase of TRAP-positive cells (Fig. S1A and B) and nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic, calcineurin-dependent 1(NFATc1) (a hallmark of the osteoclast phenotype) expression (Fig. S1C) induced by LPS in RAW264.7 cells. We also confirmed that uPA attenuated the increase of TRAP-positive cells induced by LPS and M-CSF in bone marrow-derived cells from mice (Fig. S1D). Next, we examined the possible involvement of plasmin in the uPA-attenuated inflammatory osteoclastogenesis stimulated with LPS by using the plasmin specific inhibitor α2-antiplasmin (α2AP). α2AP abrogated the uPA-attenuated increase of TRAP-positive cells and NFATc1 expression induced by LPS in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. S1E-G). Additionally, plasmin attenuated the LPS-induced increase of TRAP-positive cells (Fig. S1E and F) and NFATc1 expression (Fig. S1G) in RAW264.7 cells. We also confirmed that α2AP abrogated the uPA-attenuated increase of TRAP-positive cells, and that plasmin attenuated the LPS-induced increase of TRAP-positive cells, in bone marrow-derived cells from mice (Fig. S1H). Because it has been reported that plasmin can activate PAR-1 21, we examined the possible effect of PAR-1 on the uPA-attenuated inflammatory osteoclastogenesis induced by LPS. The PAR-1 specific antagonist SCH 79797 22 significantly and partially abrogated the uPA-attenuated increase of TRAP positive cells (Fig. S1I and J) and NFATc1 expression (Fig. S1K) induced by LPS in RAW264.7 cells. We also confirmed that SCH 79797 abrogated the uPA-attenuated increase of TRAP positive cells in bone marrow-derived cells from mice (Fig. S1L). We also confirmed that the PAR-1 agonist TFLLRN-NH2 23 significantly and partially attenuated the increase of TRAP-positive cells (Fig. S1M and N) and NFATc1 expression (Fig. S1O) induced by LPS in RAW264.7 cells. We also confirmed that TFLLRN-NH2 attenuated the LPS-induced increase of TRAP-positive cells in bone marrow-derived cells from mice (Fig. S1P).

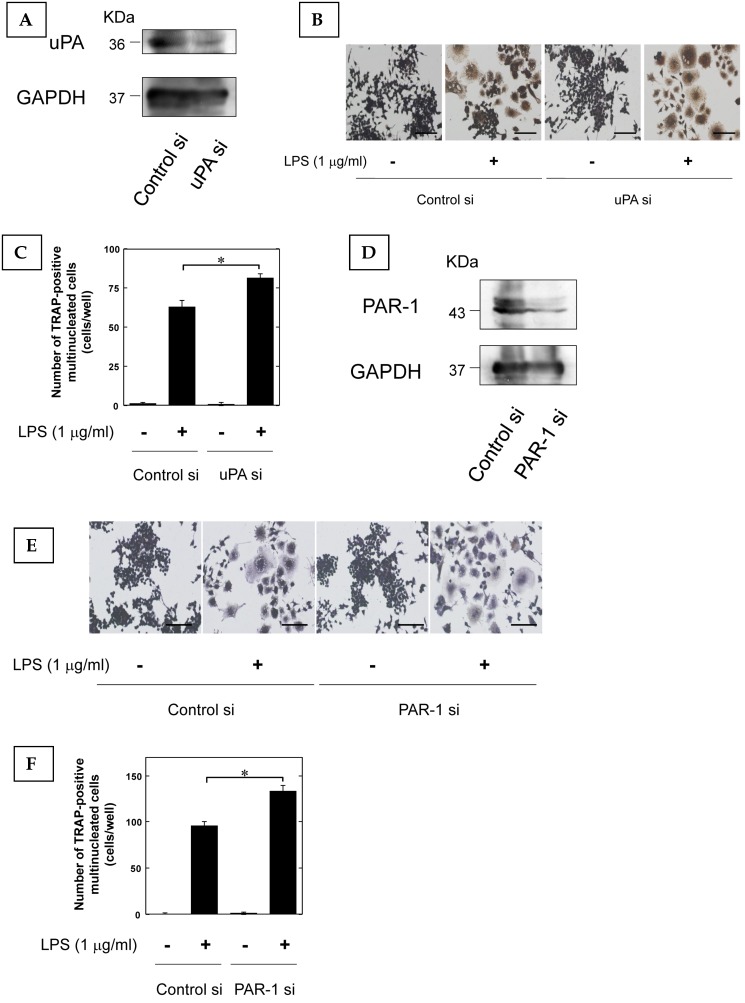

Furthermore, we examined that the effect of LPS-induced osteoclast differentiation on the reduction of uPA and PAR-1 expression by using siRNA. We confirmed that uPA and PAR-1 expression in RAW264.7 cells was attenuated by siRNA (Fig. 3A, and D, respectively). The reduction of uPA and PAR-1 expression promoted the LPS-induced increase of TRAP-positive cells in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 3B and C, Fig. 3E and F, respectively).

Figure 3.

The reduction of uPA and PAR-1 promoted inflammatory osteoclastogenesis. (A) The transfection of RAW264.7 cells with control or uPA siRNA confirms the specific depletion of uPA by Western blot analysis. (B) RAW264.7 cells tranfected with control or uPA siRNA were cultured for 3 days in the absence or presence of LPS (1 μg/ml). Then, TRAP-staining was performed to detect mature OCs. (C) Mature OCs were identified as multinucleated TRAP-positive cells (n=4). (D) The transfection of RAW264.7 cells with control or uPA siRNA confirms the specific depletion of PAR-1 by Western blot analysis. (E) RAW264.7 cells tranfected with control or PAR-1 siRNA were cultured for 3 days in the absence or presence of LPS (1 μg/ml). Then, TRAP-staining was performed to detect mature OCs. (F) Mature OCs were identified as multinucleated TRAP-positive cells (n=4). The data represent the mean ± SEM. *, P<0.01. Scale bar = 200 μm.

The AMPK pathway activated by uPA attenuated inflammatory osteoclastogenesis

Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) acts as a negative regulator during OC differentiation 18. An AMPK activator, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide 1-β-D-ribofuranoside (AICAR) 24, attenuated the increase of TRAP-positive cells (Fig. S2A and B) and NFATc1 expression (Fig. S2C) induced by LPS in RAW264.7 cells. We also confirmed that AICAR attenuated the LPS-induced increase of TRAP-positive cells in bone marrow-derived cells from mice (Fig. S2D). Next, we examined whether AMPK activation is associated with uPA-mediated inflammatory osteoclastogenesis. First, we observed that uPA induced the phosphorylation of AMPK at 60 minutes after the uPA stimulation (Fig. S2E). Additionally, we confirmed that the AMPK inhibitor compound C 25 partially suppressed the uPA-attenuated increase of TRAP-positive cells (Fig. S2F and G) and NFATc1 expression (Fig. S2H) induced by LPS in RAW264.7 cells. We also confirmed that compound C also suppressed the uPA-attenuated increase of TRAP-positive cells in bone marrow-derived cells from mice (Fig. S2I). We also examined the effect of plasmin on the uPA-activated AMPK pathway; the plasmin inhibitor α2AP attenuated the uPA-induced phosphorylation of AMPK (Fig. S2J), and plasmin and a PAR-1 agonist TFLLRN-NH2 induced AMPK phosphorylation (Fig. S2K, and L). Moreover, the PAR-1 antagonist SCH 79797 suppressed the uPA-induced AMPK phosphorylation (Fig. S2M).

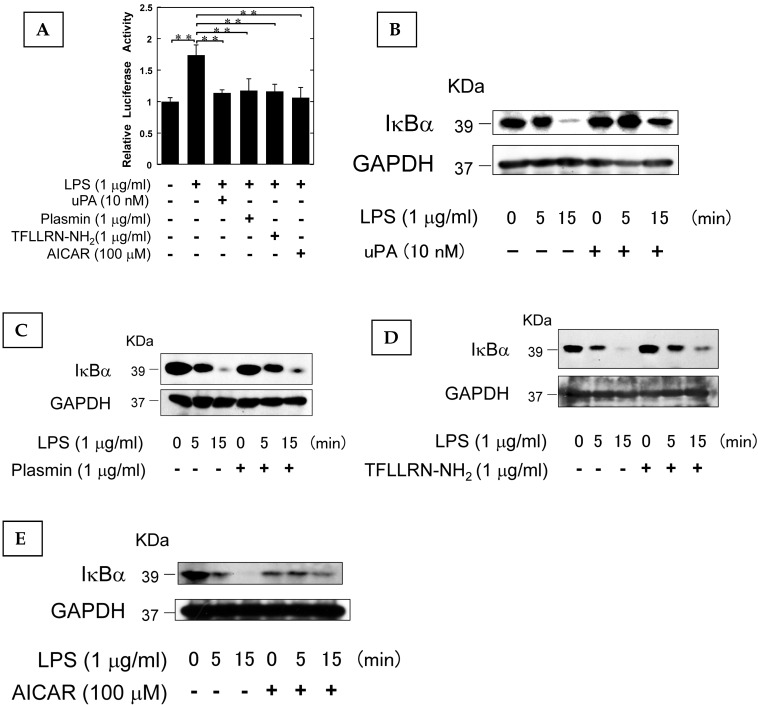

The AMPK pathway activated by uPA attenuated LPS-induced NF-κB activation

It has been reported that AMPK attenuates the NF-κB pathway which plays a pivotal role in the induction of osteoclastogenesis associated with inflammation 26-28. Therefore, we examined the effect of uPA, plasmin, PAR-1, and AMPK on the LPS-induced NF-κB transcriptional activity through the use of a functional promoter assay with NF-κB-responsive element as described in Materials and Methods. uPA, plasmin, TFLLRN-NH2, and AICAR attenuated the LPS-induced NF-κB activation (Fig. 4A). We also confirmed that uPA, plasmin, TFLLRN-NH2, and AICAR attenuated the LPS-induced IκBα degradation (Fig. 4B, C, D, and E, respectively). These data suggest that uPA, plasmin, TFLLRN-NH2, and AICAR attenuated the LPS-activated NF-κB signaling.

Figure 4.

The AMPK pathway activated by uPA attenuated LPS-induced NF-κB activation. (A) RAW264.7 cells were co-transfected with a Fluc reporter plasmind containing NF-κB promoter and the internal control vector pRL-TK. At 24 hours after the transfections, these cells were cultured in the presence or absence of 10 nM uPA, 1 μg/ml plasmin, 1 μg/ml PAR-1 agonist TFLLRN-NH2, or 100 μM AICAR for 30 minutes, and then stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS for 3 hours. Finally, the status of transcriptional activity of the promoter with NF-κB-responsive element was examined (n=3) as described in Materials and Methods. (B) RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with 10 nM uPA for 30 minutes and then stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS for the indicated periods. Degradation of IκBα was evaluated by a Western blot analysis. (C) RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with 1 μg/ml plasmin for 30 minutes and then stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS for the indicated periods. Degradation of IκBα was evaluated by a Western blot analysis. (D) RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with 1 μg/ml PAR-1 agonist TFLLRN-NH2 for 30 minutes and then stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS for the indicated periods. Degradation of IκBα was evaluated by a Western blot analysis. (E) RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with 100 μM AICAR for 30 minutes and then stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS for the indicated periods. Degradation of IκBα was evaluated by a Western blot analysis. The data represent the mean ± SEM. **, P<0.05.

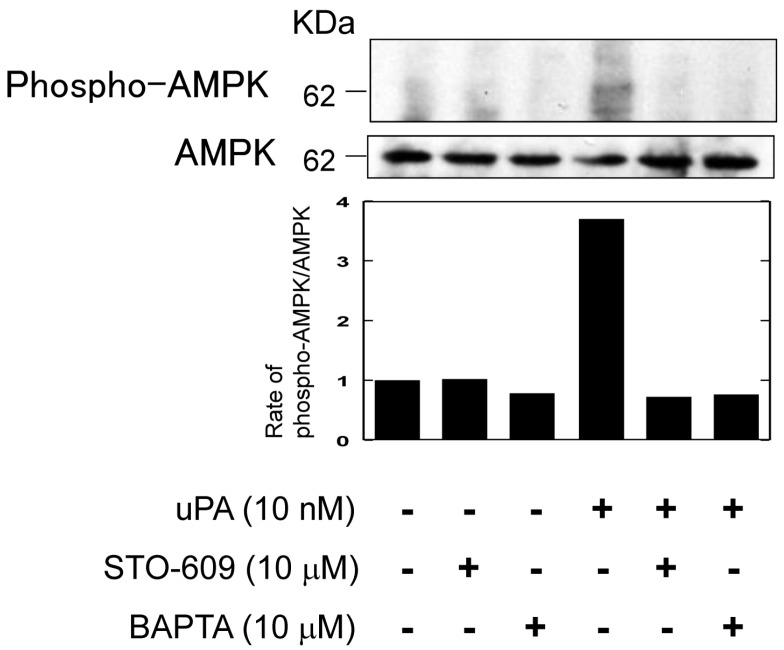

uPA activated AMPK through the Ca2+/CaMKK pathway

It has been reported that the activation of AMPK through PAR-1 is associated with Ca2+/calmodulin dependent protein kinase kinase (CaMKK) 17. Therefore, we examined whether uPA activated AMPK through Ca2+/CaMKK by using a CaMKK specific inhibitor, STO-609 and a Ca2+ chelator, BAPTA. Both STO-609 and BAPTA attenuated the uPA-induced AMPK phosphorylation (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

uPA activated AMPK through the Ca2+/CaMKK pathway. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with a CaKKK specific inhibitor STO-609 (10 μM) or a Ca2+ chelator BAPTA (10 μM) for 30 minutes and then stimulated with 10 nM uPA for 60 minutes. Phosphorylation of AMPK and total amount of AMPK were evaluated by a Western blot analysis. The histogram on the bottom panel shows quantitative representations of phospho-AMPK obtained from densitometry analysis after normalization to the levels of AMPK expression.

Discussion

Inflammation can lead to osteoclastogensis by inducing OC differentiation. However, the mechanisms underlying osteoclastogenesis induced by inflammation are not precisely understood. Although it has been reported that the plasminogen activator/plasmin system is not required for OC formation 29, we found that the uPA deficiency promoted inflammatory bone loss induced by LPS, which not only induces inflammation but also osteoclastic bone resorption 6, 8 (Fig. 1A-C). Additionally, uPA deficiency promoted inflammatory osteoclastogenesis in the bone marrow-derived cells induced by LPS (Fig. 1D, and E), and uPA treatment abrogated uPA-deficiency-promoted inflammatory osteoclastogenesis induced by LPS (Fig. 1F, and G). We herein showed for the first time the inhibitory functions of uPA on the LPS-induced inflammatory osteoclastogenesis (Fig. 1).

Next, we showed that LPS induced uPA expression in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 2A). It has been reported that LPS activates the MEK and JNK pathways, which is associated with the production of TNF-α and IL-6 30, 31. Therefore, we examined the effect of the MEK and JNK specific inhibitors in the LPS-induced uPA expression, and we showed that the LPS-induced uPA expression is associated with that the MEK and JNK pathways (Fig. 2B). Additionally, we showed the uPA treatment attenuated inflammatory osteoclastogenesis induced by LPS (Fig. S1A-D). These data suggest that the LPS-induced uPA may inhibit inflammatory osteoclastogenesis in a negative feedback loop. It has been known that uPA activates Plg into plasmin, and the uPA-generated plasmin can activate PAR-1, and Plg/plasmin and PAR-1 modulate bone metabolism 19, 32, 33. Moreover, plasmin is essential in preventing periodontitis in mice 34, and may be associated with LPS-induced inflammation. We herein showed that plasmin and PAR-1 activation attenuate inflammatory osteoclastogenesis induced by LPS (Fig. S1E-H, M-P), and the inhibition of plasmin and PAR-1 abrogated the attenuation of LPS-induced osteoclastogenesis by uPA (Fig. S1E-L). We also confirmed that the reduction of uPA and PAR-1 by siRNA promoted inflammatory osoteoclastogenesis induced by LPS (Fig. 3). These data suggest that uPA mediated the prevention of inflammatory osteoclastogenesis induced by LPS through plasmin/PAR-1 activation.

Recently, it has been reported that PAR-1 can activate AMPK 35, and the AMPK acts as a negative regulator of osteoclastogenesis 18. Additionally, many studies demonstrated that AMPK can inhibit NF-κB activation, and the inhibition of NF-κB signaling by AMPK is associated with several mediators, such as Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), p53, and Forkhead box O (FoxO) 18, 27, 28, 36-39. uPA/plasmin/PAR-1 activated AMPK (Fig. S2E, K, L), and attenuated NF-κB activation induced by LPS (Fig. 4). Additionally, the inhibition of AMPK abrogated uPA-attenuated OC differentiation induced by LPS (Fig. S2F-I). Moreover, we confirmed the uPA activates AMPK through the Ca2+/CaMKK pathway (Fig. 5), which is associated with the PAR-1-activated AMPK 17. These data strongly suggest that uPA negatively regulates the development of inflammatory osteoclastogenesis by AMPK activation through plasmin/PAR-1/Ca2+/CaMKK pathway, resulting in the inactivation of NF-κB which is required for the LPS-induced osteocastogenesis. Thus, the LPS-induced inflammatory osteoclastogenesis seems to be regulated by negative feedback loop through uPA/plasmin//PAR-1/Ca2+/CaMKK/AMPK axis. Injection of LPS to human is associated with the activation of fibrinolytic pathway 40, 41, and it has been reported that LPS induces uPA expression in multiple cells, such as human gingival fibroblasts, lung epithelial cells, pre-B lymphoma cells, cardiomyoblast cells 42-45. Additionally, a recent study demonstrated that fibrin accumulation stimulates the inflammatory response through multiple mechanisms 46, and promotes inflammatory osteoporosis 47. Therefore, uPA induced by various organs may be associated with the negative regulation of inflammatory bone loss by promoting of fibrinolysis. We herein propose that uPA has a protective effect on inflammatory osteoclastogenesis, and our findings may provide new insights into the development of clinical therapeutic approach for inflammatory bone diseases.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grants-in-aid for Scientific Research (C: 25460078 to Y. Kanno).

Author contribution

YK conceived and designed the experiments. YK, AI, EK, HK, KI, OM were involved in the experiments. YK analyzed the data. YK, AI and OM wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Lam J, Abu-Amer Y, Nelson CA. et al. Tumour necrosis factor superfamily cytokines and the pathogenesis of inflammatory osteolysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:ii82–83. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.suppl_2.ii82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baroukh B, Saffar JL. Identification of osteoclasts and their mononuclear precursors. A comparative histological and histochemical study in hamster periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 1991;26:161–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1991.tb01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature. 2003;423:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature01658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wada T, Nakashima T, Hiroshi N. et al. RANKL-RANK signaling in osteoclastogenesis and bone disease. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, Sarosi I, Yan XQ. et al. RANK is the intrinsic hematopoietic cell surface receptor that controls osteoclastogenesis and regulation of bone mass and calcium metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1566–1571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abu-Amer Y, Ross FP, Edwards J. et al. Lipopolysaccharide-stimulated osteoclastogenesis is mediated by tumor necrosis factor via its P55 receptor. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1557–1565. doi: 10.1172/JCI119679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi N, Kadono Y, Naito A. et al. Segregation of TRAF6-mediated signaling pathways clarifies its role in osteoclastogenesis. EMBO J. 2001;20:1271–1280. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Islam S, Hassan F, Tumurkhuu G. et al. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide induces osteoclast formation in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;360:346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jimi E, Aoki K, Saito H. et al. Selective inhibition of NF-kappa B blocks osteoclastogenesis and prevents inflammatory bone destruction in vivo. Nat Med. 2004;10:617–624. doi: 10.1038/nm1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mondino A, Blasi F. uPA and uPAR in fibrinolysis, immunity and pathology. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deppe H, Hohlweg-Majert B, Hölzle F. et al. Content of urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) and its inhibitor PAI-1 in oral mucosa and inflamed periodontal tissue. Quintessence Int. 2010;41:165–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baran M, Möllers LN, Andersson S. et al. Survivin is an essential mediator of arthritis interacting with urokinase signalling. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:3797–3808. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Nardo CM, Lenzo JC, Pobjoy J. et al. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator and arthritis progression: contrasting roles in systemic and monoarticular arthritis models. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R199. doi: 10.1186/ar3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braaten JV, Handt S, Jerome WG. et al. Regulation of fibrinolysis by platelet-released plasminogen activator inhibitor 1: light scattering and ultrastructural examination of lysis of a model platelet-fibrin thrombus. Blood. 1993;81:1290–1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ragno P. The urokinase receptor: a ligand or a receptor? Story of a sociable molecule. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1028–1037. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5428-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trejo J. Protease-activated receptors: new concepts in regulation of G protein-coupled receptor signaling and trafficking. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:437–442. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.052100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Yang L, Rezaie AR. et al. Activated protein C protects against myocardial ischemic/reperfusion injury through AMP-activated protein kinase signaling. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1308–1317. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee YS, Kim YS, Lee SY. et al. AMP kinase acts as a negative regulator of RANKL in the differentiation of osteoclasts. Bone. 2010;47:926–937. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanno Y, Ishisaki A, Kawashita E. et al. Plasminogen/plasmin modulates bone metabolism by regulating the osteoblast and osteoclast function. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:8952–8960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.152181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanno Y, Into T, Lowenstein CJ. et al. Nitric oxide regulates vascular calcification by interfering with TGF- signalling. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:221–230. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuliopulos A, Covic L, Seeley SK. et al. Plasmin desensitization of the PAR1 thrombin receptor: kinetics, sites of truncation, and implications for thrombolytic therapy. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4572–4585. doi: 10.1021/bi9824792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahn HS, Foster C, Boykow G. et al. Inhibition of cellular action of thrombin by N3-cyclopropyl-7-[[4-(1-methylethyl)phenyl]methyl]-7H-pyrrolo[3, 2-f]quinazoline-1,3-diamine (SCH 79797), a nonpeptide thrombin receptor antagonist. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:1425–1434. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Syeda F, Grosjean J, Houliston RA. et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 induction and prostacyclin release by protease-activated receptors in endothelial cells require cooperation between mitogen-activated protein kinase and NF-kappaB pathways. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11792–11804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corton JM, Gillespie JG, Hawley SA. et al. 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside. A specific method for activating AMP-activated protein kinase in intact cells? Eur J Biochem. 1995;229:558–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y. et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1167–1174. doi: 10.1172/JCI13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krum SA, Chang J, Miranda-Carboni G. et al. Novel functions for NFκB: inhibition of bone formation. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:607–611. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hattori Y, Suzuki K, Hattori S. et al. Metformin inhibits cytokine-induced nuclear factor kappaB activation via AMP-activated protein kinase activation in vascular endothelial cells. Hypertension. 2006;47:1183–1188. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000221429.94591.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang C, Li L, Zhang ZG. et al. Globular adiponectin inhibits angiotensin II-induced nuclear factor kappaB activation through AMP-activated protein kinase in cardiac hypertrophy. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222:149–155. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daci E, Udagawa N, Martin TJ. et al. The role of the plasminogen system in bone resorption in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:946–952. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Du SL, Yuan X, Zhan S. et al. Trametinib, a novel MEK kinase inhibitor, suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α production and endotoxin shock. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;458:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.01.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee YS, Lan Tran HT, Van Ta Q. Regulation of expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 by JNK in Raw 264.7 cells: presence of inhibitory factor(s) suppressing MMP-9 induction in serum and conditioned media. Exp Mol Med. 2009;41:259–268. doi: 10.3858/emm.2009.41.4.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song SJ, Pagel CN, Campbell TM. et al. The role of protease-activated receptor-1 in bone healing. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:857–868. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62306-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen K, Murphy CM, Chan B. et al. Activated protein C (APC) can increase bone anabolism via a protease-activated receptor (PAR)1/2 dependent mechanism. J Orthop Res. 2014;32:1549–1556. doi: 10.1002/jor.22726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sulniute R, Lindh T, Wilczynska M. et al. Plasmin is essential in preventing periodontitis in mice. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:819–828. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stahmann N, Woods A, Carling D. et al. Thrombin activates AMP-activated protein kinase in endothelial cells via a pathway involving Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase beta. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:5933–5945. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00383-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Z, Kahn BB, Shi H. et al. Macrophage alpha1 AMP-activated protein kinase (alpha1AMPK) antagonizes fatty acid-induced inflammation through SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:19051–19059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salminen A, Hyttinen JM, Kaarniranta K. AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits NF-κB signaling and inflammation: impact on healthspan and lifespan. J Mol Med (Berl) 2011;89:667–676. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0748-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu X, Mahadev K, Fuchsel L. et al. Adiponectin suppresses IkappaB kinase activation induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha or high glucose in endothelial cells: role of cAMP and AMP kinase signaling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E1836–1844. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00115.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Indo Y, Takeshita S, Ishii KA. et al. Metabolic regulation of osteoclast differentiation and function. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:2392–2399. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Deventer SJ, Büller HR, ten Cate JW. et al. Experimental endotoxemia in humans: analysis of cytokine release and coagulation, fibrinolytic, and complement pathways. Blood. 1990;76:2520–2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suffredini AF, Harpel PC, Parrillo JE. Promotion and subsequent inhibition of plasminogen activation after administration of intravenous endotoxin to normal subjects. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1165–1172. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198905043201802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bodet C, Andrian E, Tanabe S. et al. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans lipopolysaccharide regulates matrix metalloproteinase, tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase, and plasminogen activator production by human gingival fibroblasts: a potential role in connective tissue destruction. J Cell Physiol. 2007;212:189–194. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shetty SK, Marudamuthu AS, Abernathy D. et al. Regulation of urokinase expression at the posttranscription level by lung epithelial cells. Biochemistry. 2012;51:205–213. doi: 10.1021/bi201293x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niiya K, Shinbo M, Ozawa T. et al. Modulation of urokinase-type plasminogen activator gene expression by inflammatory cytokines in human pre-B lymphoma cell line RC-K8. Thromb Haemost. 1995;74:1511–1515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng YC, Chen LM, Chang MH. et al. Lipopolysaccharide upregulates uPA, MMP-2 and MMP-9 via ERK1/2 signaling in H9c2 cardiomyoblast cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;325:15–23. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-0016-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davalos D, Akassoglou K. Fibrinogen as a key regulator of inflammation in disease. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34:43–62. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cole HA, Ohba T, Nyman JS. et al. Fibrin accumulation secondary to loss of plasmin-mediated fibrinolysis drives inflammatory osteoporosis in mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2222–2233. doi: 10.1002/art.38639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures.