Abstract

FeII, CoII and NiII complexes of two tetraazamacrocycles (1,4,8,11-tetrakis(carbamoylmethyl)-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (L1) and 1,4,7,10-tetrakis(carbamoylmethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane (L2) show promise as paraCEST agents for registration of temperature (paraCEST = paramagnetic Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer). The FeII, CoII and NiII complexes of L1 show up to four CEST peaks shifted ≤ 112 ppm, whereas analogous complexes of L2 show only a single CEST peak at ≤ 69 ppm. Comparison of the temperature coefficients (CT) of the CEST peaks of [Co(L2)]2+, [Fe(L2)]2+, [Ni(L1)]2+ and [Co(L1)]2+ showed that a CEST peak of [Co(L1)]2+ gave the largest CT (−0.66 ppm/°C at 4.7 T). NMR spectral and CEST properties of these complexes correspond to coordination complex symmetry as shown by structural data. The [Ni(L1)]2+ and [Co(L1)]2+ complexes have a six-coordinate metal ion bound to the 1-, 4- amide oxygens and four nitrogens of the tetraazamacrocycle. The [Fe(L2)]2+ complex has an unusual eight-coordinate FeII bound to four amide oxygens and four macrocyclic nitrogens. For [Co(L2)]2+, one structure has seven-coordinate CoII with three bound amide pendents and a second structure has a six-coordinate CoII with two bound amide pendents.

Keywords: macrocycles, NMR spectroscopy, CEST, MRI

Introduction

Paramagnetic transition metal ion complexes have applications as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents. For example, high spin MnII and FeIII complexes have been studied as alternatives to GdIII T1 relaxivity contrast agents.[1] Transition metal ions have also been studied as paraCEST MRI contrast agents (paraCEST = paramagnetic chemical exchange saturation transfer).[2] ParaCEST agents have ligand protons that exchange with bulk water. Exchange rate constants must be sufficiently low to produce distinct proton resonances for paraCEST agent and bulk water, giving rise to the requirement that the rate constant for proton exchange is less than the frequency difference between bulk water and contrast agent protons (kex< Δω).[3] Selective saturation of the contrast agent pool of protons with a radiofrequency pulse in concert with proton exchange results in a decrease in the signal of the bulk water pool of protons.[3a] The paramagnetic metal center of paraCEST agents produces a hyperfine shift in the exchangeable ligand protons to give a large Δω.[4] The large Δω makes it feasible to have rapid rates of proton exchange, while maintaining distinct proton resonances for contrast agent and bulk water. In addition, a large Δω is useful for shifting the CEST effect far from the magnetization transfer effect of tissue.[4a]

Most paraCEST agents reported to date are LnIII complexes.[4–5] Until recently, transition metal ions have been overlooked in the development of paraCEST agents, despite their long history as paramagnetic shift agents.[6] Paramagnetic metal ions that are useful for paraCEST show highly dispersed proton resonances that are often relatively sharp. Such paramagnetic centers have relatively low T1 and T2 relaxivity, yet produce large hyperfine shifts. FeII, CoII and NiII complexes have magnetic properties that produce shift agents and are thus suitable for development as paraCEST agents.[2, 7]

The diverse coordination chemistry of FeII, CoII and NiII opens up new opportunities in the design of ligands for paraCEST agents. For example, ligand donor groups used for transition metal ion paraCEST agents to date include aminopyridines,[2c] alcohols,[7a] benzimidazoles,[2d, 8] pyrazoles[2a] and amides.[2b, e, 9] These ligands all contain OH or NH protons that exchange with water protons to produce the CEST effect. In addition to providing exchangeable protons, macrocyclic ligands for these metal ions must produce complexes with a large degree of kinetic inertness for in vivo studies.[10] Also for CEST considerations, the symmetry of the metal ion complex is important in terms of the shift, intensity and number of CEST peaks. For example, macrocyclic ligands that are based on 1,4,7-triazacyclododecane (TACN) with three pendents give highly inert complexes of FeII, CoII and NiII with six-coordinate metal ion centers.[2b, c, e] These TACN complexes generally give simple proton NMR spectra and a single CEST peak, consistent with the symmetry of the complexes. Tetraazamacrocycles containing four pendent amide groups (L1, L2 in Scheme 1) also form highly inert complexes with these metal ions.[7a] However, these potentially octadentate ligands are anticipated to show unusual geometries with these typically 6-coordinate metal ions. CEST NMR and MRI data from our previous studies suggested that the coordination geometry of the tetraazamacrocyclic complexes (L1 and L2) of CoII or FeII, NiII was variable.[2b, e, 7a] For example, [Co(L1)]2+ produced four highly shifted CEST peaks attributed to four magnetically inequivalent amide protons while [Co(L2)]2+ produced a single moderately shifted CEST peak.[2e] [Fe(L2)]2+ gave proton NMR and CEST spectra that were most consistent with an unusual eight coordinate complex.[7a]

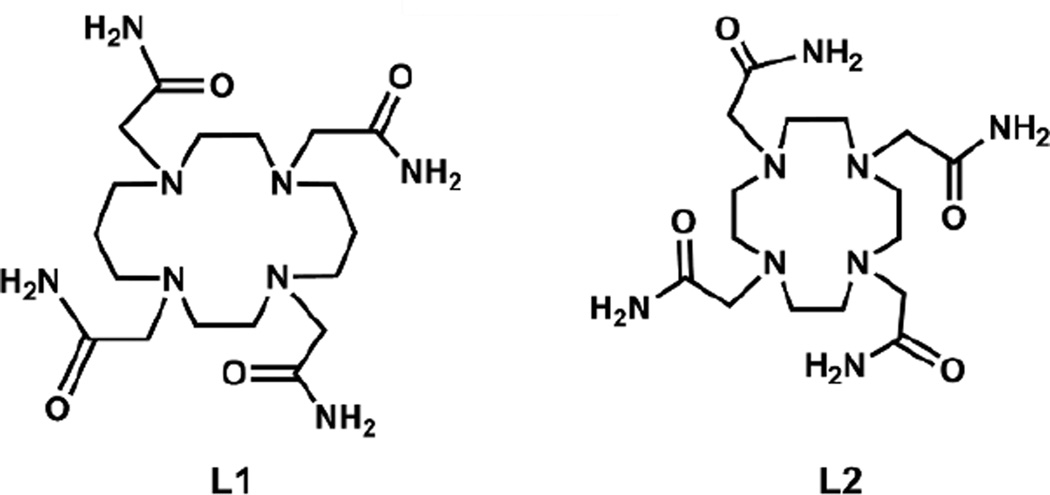

Scheme 1.

Chemical structure of macrocyclic ligands.

Macrocyclic complexes of FeII, CoII, or NiII with amide pendent groups often produce sharp, highly shifted CEST peaks attributed to NH proton exchange. For CoII in particular, CEST peaks may be narrow and intense, in part due to the low T1 relaxivity of these complexes.[2a, e] The moderate proton exchange rate constants of amide NH protons are also responsible, in part, for the relatively sharp CEST peaks observed at physiological temperatures and pH values. These moderate rate constants for proton exchange led us to consider temperature dependent imaging studies. We anticipated that exchange broadening would be limited because rate constants would remain less than Δω, even at higher temperatures for imaging. In addition, the amide CEST peaks that are highly shifted correspond to protons that have large hyperfine shifts from the paramagnetic center. Such proton chemical shifts that have a large hyperfine contribution have a large temperature dependence which is favorable for thermometry.[11] The linear relationship between the CEST peak position and temperature produces a straightforward means to register temperature over a moderate range.

There is much interest in temperature responsive agents for mapping of tissue temperature gradients.[5a, 12] Currently, proton relaxation frequencies (PRF) are the gold standard for temperature mapping by non-invasive methods.[13] However, the proton temperature sensitivity of pure water at 0.01 ppm/°C is not large, and thus there is interest in paraCEST thermometry because of the larger temperature dependent shifts. For example, the first paraCEST agents reported for thermometry applications were LnIII complexes of derivatives of 1,4,7,10-tetrakis(carbamoylmethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane (DOTAM).[14] A CT value of −0.30 ppm/°C was reported for the CEST peak of EuIII-DOTAM–Gly-Phe which is attributed to the CEST effect of water ligand protons.[14a] However, the intensity of the CEST peak decreases substantially at high temperature due to exchange broadening. A related complex, TmIII-DOTAM t-butyl, has an even higher temperature dependence of 0.57 ppm/°C for the exchangeable amide NH protons.[14b] Two FeII complexes suitable for paraCEST thermometry with CT values of 0.23 and 1.02 ppm/°C were reported as the first example of a transition metal ion paraCEST agent for thermometry.[15] The complex with the largest CT value undergoes a change in spin state (spin cross-over) upon heating from S = 0 to S = 2.

Here we present studies of FeII, CoII and NiII complexes of two different amide–appended tetraazamacrocyclic complexes. Their application as temperature responsive paraCEST agents is studied for the first time (Scheme 1). Towards in vivo studies, several of these complexes are shown to produce CEST contrast in rabbit serum, which demonstrates minimal effect of blood proteins on CEST spectra or CEST MRI contrast. The crystal structures of several of these complexes were obtained in order to better understand the molecular symmetry of the complexes and their corresponding CEST spectra for this new class of paraCEST agents.

Results

Molecular structures

The crystal structures of CoII complexes of L1 and L2, the FeII complex of L2, and the NiII complex of L1 were solved to study the coordination of the potentially octadentate ligands, L1 and L2, to these metal ions. Knowledge of the coordination geometry is important for the analysis of hyperfine proton shifts, solution chemistry and CEST spectra of these complexes.

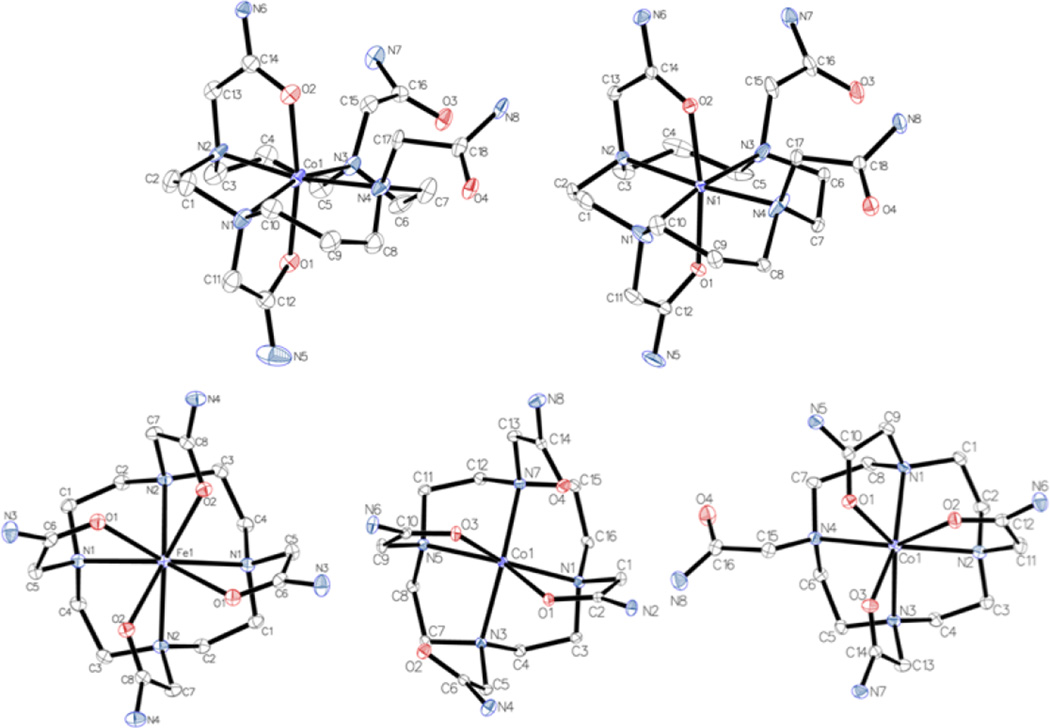

Crystallographic data is given for all obtained structures in Table 1 and selected bond lengths and angles are summarized in Table 2. The structure of [Ni(L1)](H2O)(CF3SO3)2 and [Co(L1)](H2O)(CH3OH)Cl2 are six coordinate complexes with donor groups consisting of the carbonyl oxygens of the 1-, 4- pendent groups and the four nitrogen donor atoms of the tetraazamacrocycle (Figure 1). The amide pendent groups coordinate through the oxygens in trans-configuration to encapsulate the metal ion center and give rise to distorted octahedral NiII and CoII complexes. In these structures, the four cyclam amine nitrogens are not planar and the trans-nitrogen metal angles are less than 180°. For example, the N1-Co-N3 bond angle is 162° and N1-Ni-N3 bond angle is 169°. Pendent amide groups give Ni-O (2.04–2.10 Å) and Co-O (2.05–2.09 Å) bond lengths which are slightly shorter than the macrocyclic amine Ni-N (2.10–2.15 Å) or Co-N (2.14–2.21 Å) bond lengths.

Table 1.

Crystal data and structural refinement details for [Co(L1)]Cl2•H2O•CH3OH, [Ni(L1)](CF3SO3)2•H2O, [Fe(L2)]X2•H2O, [Co(L2–6)]X2 •3H2O, and [Co(L2–7)]X2•CH3OH, where X is a mixture of Cl and Br.

| Identification code | Co(L1)]Cl2•H2O•CH3OH | Ni(L1)](CF3SO3)2•H2O | [Fe(L2)]X2•H2O | [Co(L2–6)]X2•3H2O | [Co(L2–7)]X2•CH3OH |

| Empirical formula | C19H42Cl2CoN8O6 | C20H38F6N8NiO11S2 | C16H36Br1.26Cl0.74FeN8O6 | C16H38Br0.17Cl1.83CoN8O7 | C17H36Cl2CoN8O5 |

| Formula weight | 608.43 | 803.41 | 619.3 | 592.15 | 562.37 |

| Temperature/K | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| Crystal system | triclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic | triclinic | orthorhombic |

| Space group | P-1 | P21/n | C2/c | P-1 | P212121 |

| a (Å) | 9.1935(8) | 15.9119(6) | 18.6290(7) | 8.5825(4) | 9.6937(4) |

| b (Å) | 9.3279(8) | 10.6542(4) | 13.6788(5) | 11.3029(5) | 10.7101(4) |

| c (Å) | 17.5746(15) | 18.6045(7) | 10.5888(4) | 13.7537(6) | 23.1393(10) |

| α (°) | 76.404(3) | 90 | 90 | 96.4863(11) | 90 |

| β (°) | 78.495(3) | 96.6425(8) | 110.5407(8) | 95.1155(10) | 90 |

| γ (°) | 84.948(3) | 90 | 90 | 108.6776(10) | 90 |

| Volume (Å3) | 1434.1(2) | 3132.8(2) | 2526.72(16) | 1244.67(10) | 2402.33(17) |

| Z | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| ρcalcg (cm3) | 1.409 | 1.703 | 1.628 | 1.58 | 1.555 |

| μ(mm−1) | 0.832 | 0.857 | 2.715 | 1.22 | 0.983 |

| F(000) | 642 | 1664 | 1275 | 620 | 1180 |

| Crystal size (mm3) | 0.08 × 0.08 × 0.01 | 0.3 × 0.3 × 0.25 | 0.2 × 0.18 × 0.15 | 0.13 × 0.08 × 0.06 | 0.2 × 0.1 × 0.05 |

| Radiation | MoKα (λ = 0.71073) | MoKα (λ = 0.71073) | MoKα (λ = 0.71073) | MoKα (λ = 0.71073) | MoKα (λ = 0.71073) |

| 2Θ range for data collection (°) | 4.496 to 49.5 | 3.192 to 67.556 | 3.78 to 67.64 | 3 to 67.54 | 3.52 to 67.796 |

| Index ranges | −10 ≤ h ≤ −10, −10 ≤ k ≤ 10, −20 ≤ l ≤ 20 | −24 ≤ h ≤ 24, −16 ≤ k ≤ 16, −28 ≤ l ≤ 28 | −29 ≤ h ≤ 29, −21 ≤ k ≤ 21, −16 ≤ l ≤ 16 | −13 ≤ h ≤ 13, −17 ≤ k ≤ 17, −21 ≤ l ≤ 21 | −15 ≤ h ≤ 15, −16 ≤ k ≤ 16, −35 ≤ l ≤ 35 |

| Reflections collected | 16641 | 84545 | 34340 | 34486 | 46188 |

| Independent reflections | 4874 [Rint = 0.1087, Rsigma = 0.1424] | 12527 [Rint = 0.0270, Rsigma = 0.0158] | 5060 [Rint = 0.0301, Rsigma = 0.0190] | 9918 [Rint = 0.0308, Rsigma = 0.0327] | 9649 [Rint = 0.0387, Rsigma = 0.0368] |

| Data/restraints/par ameters | 4874/1/318 | 12527/0/524 | 5060/0/154 | 9918/0/326 | 9649/0/339 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 0.991 | 1.021 | 1.038 | 1.036 | 1.062 |

| Final R indexes [I>=2σ (I)] | R1 = 0.0754, wR2 = 0.1736 | R1 = 0.0296, wR2 = 0.0755 | R1 = 0.0230, wR2 = 0.0551 | R1 = 0.0322, wR2 = 0.0871 | R1 = 0.0413, wR2 = 0.1130 |

| Final R indexes [all data] | R1 = 0.1300, wR2 = 0.1893 | R1 = 0.0342, wR2 = 0.0790 | R1 = 0.0286, wR2 = 0.0570 | R1 = 0.0413, wR2 = 0.0913 | R1 = 0.0463, wR2 = 0.1165 |

| Largest diff. peak/hole / e Å−3 | 1.11/−0.63 | 0.76/−0.99 | 1.10/−0.35 | 0.84/−0.47 | 1.90/−0.99 |

| Flack parameter | - | - | - | - | 0.123(6) |

Table 2.

Selected bond distances and angles for [Co(L1)]Cl2•H2O•CH3OH, [Ni(L1)](CF3SO3)2•H2O, [Fe(L2)]X2•H2O, [Co(L2–6)]X2 •3H2O, and [Co(L2–7)]X2•CH3OH (X represents a mixture of Cl and Br).

| Select Bond Distances and Bond Angles | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Co(L1)](H2O)(CH3OH)Cl2 | [Ni(L1)](H2O)(CF3SO3)2 | [Fe(L2)]X2•H2O | [Co(L2–6)]X2•3H2O | [Co(L2–7)]X2•CH3OH | |||||

| Bond | Distance (Å) | Bond | Distance (Å) | Bond | Distance (Å) | Bond | Distance (Å) | Bond | Distance (Å) |

| Co1-O1 | 2.086(4) | Ni1-O1 | 2.0994(8) | Fe1-O1 | 2.2791(8) | Co1-O1 | 2.0964(9) | Co1-O1 | 2.093(2) |

| Co1-O2 | 2.058(4) | Ni1-O2 | 2.0437(7) | Fe1-O2 | 2.3184(8) | Co1-O3 | 2.0764(9) | Co1-O2 | 2.355(2) |

| Co1-N1 | 2.159(5) | Ni1-N1 | 2.1204(9) | Fe1-N1 | 2.3688(9) | Co1-N1 | 2.2197(11) | Co1-O3 | 2.113(2) |

| Co1-N2 | 2.157(5) | Ni1-N2 | 2.1019(8) | Fe1-N2 | 2.3611(9) | Co1-N3 | 2.2621(11) | Co1-N1 | 2.202(4) |

| Co1-N3 | 2.152(5) | Ni1-N3 | 2.1455(9) | Co1-N5 | 2.2608(10) | Co1-N2 | 2.341(4) | ||

| Co1-N4 | 2.212(5) | Ni1-N4 | 2.1246(10) | Co1-N7 | 2.2367(11) | Co1-N3 | 2.286(4) | ||

| Co1-N4 | 2.397(4) | ||||||||

| Angle | Degree(°) | Angle | Degree(°) | Angle | Degree(°) | Angle | Degree(°) | Angle | Degree(°) |

| O1-Co1-N1 | 76.93(17) | O1-Ni1-N1 | 79.33(3) | O1-Fe1-O1* | 110.82(4) | O1-Co1-N1 | 75.77(4) | O1-Co1-O2 | 75.69(9) |

| O1-Co1-N2 | 91.97(17) | O1-Ni1-N2 | 91.49(3) | O1-Fe1-O2 | 71.71(3) | O1-Co1-N3 | 90.93(4) | O1-Co1-O3 | 80.62(9) |

| O1-Co1-N3 | 85.20(17) | O1-Ni1-N3 | 89.99(4) | O1-Fe1-O2* | 72.26(3) | O1-Co1-N5 | 151.34(4) | O1-Co1-N1 | 78.83(12) |

| O1-Co1-N4 | 99.06(17) | O1-Ni1-N4 | 95.02(4) | O1-Fe1-N1 | 69.72(3) | O1-Co1-N7 | 127.14(4) | O1-Co1-N2 | 142.27(12) |

| O2-Co1-O1 | 170.18(17) | O2-Ni1-O1 | 171.91(3) | O1-Fe1-N1* | 156.05(3) | O1-Co1-O3 | 85.80(4) | O1-Co1-N3 | 142.62(12) |

| O2-Co1-N1 | 96.30(17) | O2-Ni1-N1 | 95.57(3) | O1-Fe1-N2 | 87.73(3) | O3-Co1-N1 | 154.95(4) | O1-Co1-N4 | 79.78(11) |

| O2-Co1-N2 | 80.34(17) | O2-Ni1-N2 | 81.84(3) | O1-Fe1-N2* | 128.38(3) | O3-Co1-N3 | 117.52(4) | O2-Co1-N4 | 153.72(11) |

| O2-Co1-N3 | 101.67(17) | O2-Ni1-N3 | 95.17(4) | O2-Fe1-O2* | 114.00(4) | O3-Co1-N5 | 76.68(4) | O3-Co1-O2 | 87.24(9) |

| O2-Co1-N4 | 88.64(17) | O2-Ni1-N4 | 91.62(3) | O2-Fe1-N1 | 127.43(3) | O3-Co1-N7 | 99.17(4) | O3-Co1-N1 | 159.45(13) |

| N1-Co1-N4 | 96.11(19) | N1-Ni1-N3 | 169.26(4) | O2-Fe1-N1* | 86.35(3) | N1-Co1-N3 | 80.13(4) | O3-Co1-N2 | 118.14(12) |

| N2-Co1-N1 | 85.83(19) | N1-Ni1-N4 | 94.62(4) | O2-Fe1-N2 | 68.88(3) | N1-Co1-N5 | 126.66(4) | O3-Co1-N3 | 74.34(11) |

| N2-Co1-N4 | 168.96(18) | N2-Ni1-N1 | 85.92(4) | O2-Fe1-N2* | 156.65(3) | N1-Co1-N7 | 79.44(4) | O3-Co1-N4 | 98.03(12) |

| N1-Co1-N3 | 162.03(19) | N2-Ni1-N3 | 95.45(4) | N1-Fe1-N1* | 120.06(4) | N3-Co1-N5 | 77.72(4) | N1-Co1-O2 | 87.30(12) |

| N2-Co1-N3 | 96.79(18) | N2-Ni1-N4 | 173.46(4) | N1-Fe1-N2 | 75.22(3) | N3-Co1-N7 | 129.51(4) | N1-Co1-N2 | 78.97(14) |

| N3-Co1-N4 | 84.73(19) | N3-Ni1-N4 | 85.23(5) | N1-Fe1-N2* | 75.14(3) | N5-Co1-N7 | 78.60(4) | O3-Co1-N4 | 123.67(14) |

| N2-Fe1-N2* | 118.41(4) | N1-Co1-N4 | 78.77(14) | ||||||

| N2-Co1-O2 | 73.15(11) | ||||||||

| N2-Co1-N4 | 124.69(13) | ||||||||

| N3-Co1-O2 | 129.16(12) | ||||||||

| N3-Co1-N2 | 74.93(14) | ||||||||

| N3-Co1-N4 | 76.79(14) | ||||||||

Table Notes: [*] denotes a specific atom in a symmetry related pair of atoms.

Figure 1.

ORTEP plot of the cations of [Co(L1)]Cl2•H2O•CH3OH (top left), [Ni(L1)](CF3SO3)2•H2O (top right), [Fe(L2)]X2•H2O (bottom left), [Co(L2–6)]X2 •3H2O (center), and [Co(L2–7)]X2•CH3OH, (bottom right). Ellipsoid set at 50 %, while hydrogen atoms were removed for clarity (X represents a mixture of Cl and Br).

Crystal data and refinement parameters for [Fe(L2)]X2•H2O (X = Cl or Br) and for two different structures of the CoII complex, [Co(L2–6)]X2 •3H2O and [Co(L2–7)]X2•CH3OH are given in Table 1, and selected bond lengths and angles in Table 2. The structures of all of the complex cations are shown in Figure 1. [Fe(L2)]2+ is an unusual example of an eight-coordinate FeII complex. The FeII center is bound to four amide pendent carbonyl oxygens and to the four macrocyclic amines. The crystallographically imposed axis of symmetry present in the [Fe(L2)] complex gives rise to two types of Fe-N and Fe-O bonds (Table 2). The bond lengths of the Fe1-O1, Fe1-O2, Fe1-N1, and Fe1-N2 are 2.2791 (8), 2.3184 (8), 2.3688(9), and 2.3611 (9) Å, respectively. The nitrogen atoms of the macrocyclic amines can be considered to form a plane (N4) and the amide oxygens a second square plane (O4). The FeII ion is sandwiched between at 1.196 Å from the N4 plane and 1.278 Å from the O4 plane. The complex cation has a distorted square antiprismatic geometry with the two planes rotated with respect to each other to give a twist angle of −27.90 between O1 and N1, and −27.47 between O2 and N2. [Co(L2–7)]X2•CH3OH has a seven coordinate Co(II) coordinated to three pendent carbonyl oxygens and four nitrogen donors of the macrocyclic ring. The geometry is best described as capped trigonal prismatic with N4 in the capping position. The seven-coordinate complex has a disordered macrocyclic ring, but well-defined pendent groups. [Co(L2–6)]X2•3H2O is six-coordinate with only two pendent amides bound to the metal center. The bonds lengths of Co1-O1 and Co1-O3 are 2.0964(9) and 2.0764(9) respectively, while the bond lengths of Co1-N1, Co1-N3, Co1-N5, and Co1-N7 are 2.2197(11), 2.2621(11), 2.2608(10), and 2.2367(11) Å respectively. While superficially appearing to be bonds, the distances from Co1 to O2 and Co1 to O4 for are 3.372 Å and 2.858 Å respectively, far too long to be considered as such. As expected, with the lower coordination number the bond distances for the six-coordinate complexes are, on average, substantially less than those for the seven-coordinate complex. In comparing the [Co(L1)]2+ complex cation with [Co(L2–6)]2+, it is notable that Co-O bond lengths are similar, but Co-N bond lengths are noticeably shorter for the [Co(L1)]2+ complex compared to [Co(L2–6)]2+. This is striking considering that each complex has the same donor groups bound to the metal center.

Solution characterization

The solution chemistry of the [Fe(L1)]2+ and [Ni(L2)]2+ complexes was studied for comparison to solution data for the other four complexes that were previously communicated.[2b, e, 7a, 10] 1H NMR studies of [Co(L1)]2+, [Ni(L1)]2+, [Co(L2)]2+ and [Fe(L2)]2+ showed that the complexes were inert towards loss of metal ion in solution over several days in the presence of competing cations such as ZnII or CuII, or with high concentrations of anions such as 25 mM carbonate or 0.40 mM phosphate. Similarly, [Ni(L2)]2+ showed no change in absorbance upon incubation with a 5-fold excess of CuII at pH 6.0 over a period of several hours, consistent with a large degree of kinetic inertia to loss of NiII (Figure S1). The [Fe(L1)]2+ complex is the exception. Solutions of the complex slowly changed color and formed precipitates in D2O or in buffered H2O at pH 7.4, suggesting that the complex is not stable under these conditions.

The 1H NMR spectra of FeII and CoII complexes of L1 are sufficiently well resolved to provide information on solution chemistry. The CoII complex in particular has highly dispersed proton resonances with twenty-four paramagnetically shifted resonances in deuterium oxide. This is consistent with solid state structural data which shows twenty-four inequivalent non-exchangeable protons for the [Co(L1)]2+ cation. The proton resonances of [Fe(L1)]2+ are slightly less highly dispersed. Experiments were carried out on this complex in d3-acetonitrile to minimize decomposition (Figure S2). Under these conditions, there are twenty-six paramagnetically shifted proton resonances, including two amide NH protons that would not be observed in D2O. These spectra are most consistent with a single major isomer in solution for the CoII and FeII complexes. The 1H NMR spectrum of [Ni(L1)]2+ has broad macrocyclic proton and pendent CH2 proton resonances. The peak broadening is attributed to the relatively long electronic relaxation times observed for six-coordinate NiII.[7a, 16]

The 1H NMR spectrum of [Ni(L2)]2+ in either DMSO or in D2O also shows broad resonances characteristic of paramagnetic six-coordinate NiII complexes (Figure S3). Amide NH protons, identified by comparison of the two NMR spectra, were observed at approximately 75 ppm as supported by their disappearance upon addition of D2O. The 1H NMR spectra of FeII and CoII complexes of L2, as communicated previously,[2b, e] also feature broad resonances for non-exchangeable macrocyclic protons.

CEST Spectroscopy

CEST spectra are plotted as the percent reduction of the water signal as a function of the frequency of the presaturation pulse. Important features of the CEST spectra for the complexes are summarized in Table 3 and CEST spectra are given in Figures 2, S4, and S5. The chemical shift of the CEST peaks of the complexes versus bulk water (Δω) and the CEST peak intensity, tabulated as saturation transfer, are given. Notably, all of the L2 complexes produced a single CEST peak that ranged from 45 to 69 ppm versus bulk water. In contrast, [Co(L1)]2+ has four major CEST peaks, [Fe(L1)]2+ has two CEST peaks and [Ni(L1)]2+ has one CEST peak ranging from 45 to 112 ppm versus bulk water. The intensities of the CEST effect ranged from 6% to 32% for solutions containing 10 mM paraCEST agent.

Table 3.

Summary of CEST spectra of FeII, CoII and NiII complexes at 11.7 T.

| Complex | Δω (ppm)a |

% CESTb | CT (ppm/°C)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| [Co(L1)]2+ | 112 | 31.5 ± 0.2 | −0.56 |

| [Co(L1)]2+ | 95 | 27.9 ± 0.3 | −0.44 |

| [Co(L1)]2+ | 54 | 19.8 ± 0.2 | −0.43 |

| [Co(L1)]2+ | 45 | 26.6 ± 0. 3 | −0.36 |

| [Ni(L1)]2+ | 76 | 12.7 ± 0.9 | −0.33 |

| Fe(L1)]2+ | 64, 78 | <10%d | - |

| [Fe(L2)]2+ | 50 | 24.0 ± 1.1 | −0.15 |

| [Co(L2)]2+ | 45 | 21.0 ± 0.1 | −0.12 |

| [Ni(L2)]2+ | 69 | 6% | - |

The chemical shift of the furthest downfield shifted amide (NH) exchangeable proton versus the water proton resonance at 37 °C.

% CEST of 10 mM paraCEST agent in 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.3–7.4, B1= 24 µT at 37 °C calculated as (1-Mz/Mo)×100.

Temperature coefficient of 10 mM paraCEST agent in 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.3–7.4, B1= 24 µT.

Low value reflects reactivity of complex in solution.

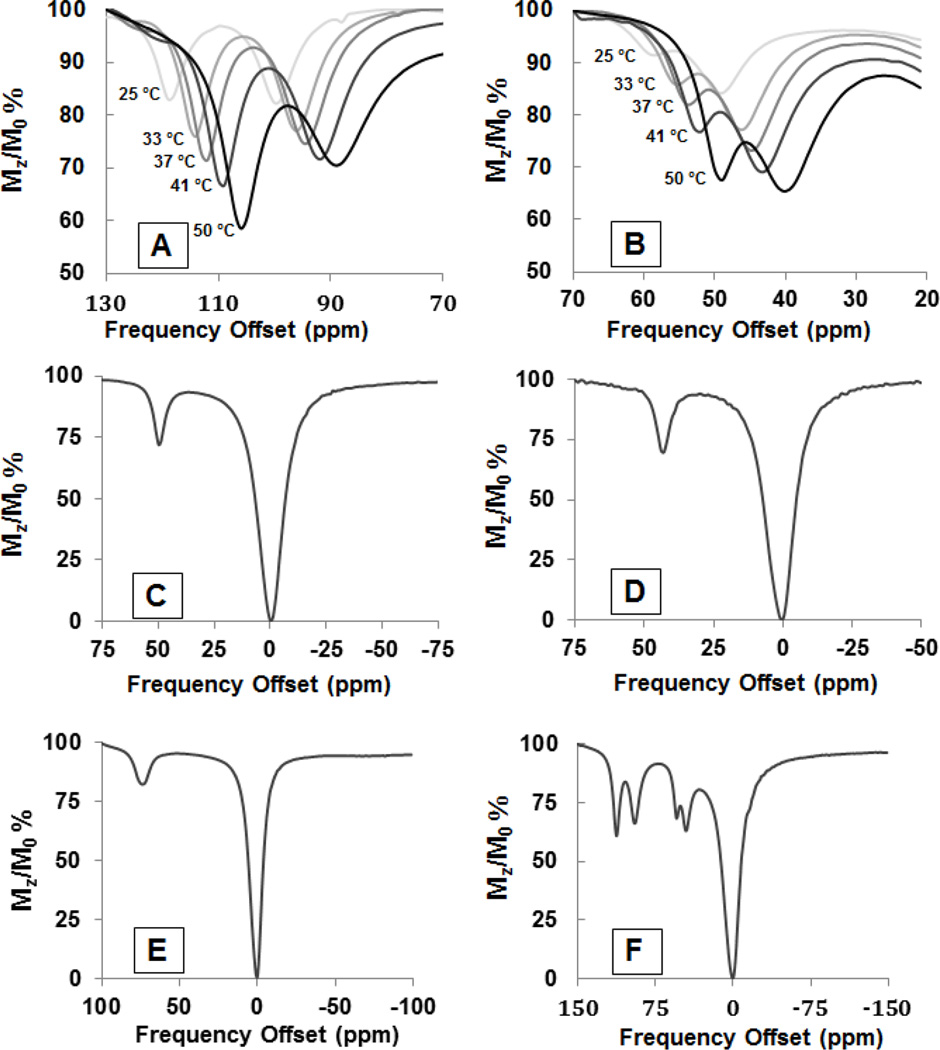

Figure 2.

CEST spectra A and B display overlaid CEST spectra at varying temperatures (25,33,37,41,50 °C of 10 mM [Co(L1)]2+, 20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, B=24µT for 2 seconds. (A shows the two furthest shifted CEST peaks, B shows the two closest peaks to bulk water, and all the CEST peaks moves toward bulk water and increases in intensity as temperature increases). CEST spectra C-F were solutions containing C) 10 mM [Fe(L2)]2+,D) [Co(L2)]2+,E) [Ni(L1)]2+,and F) [Co(L1)]2+ in rabbit serum, pH 7.5, recorded at 11.7 T, with a RF presaturation pulse applied for 2 seconds, B= 24 µT at 37°C.

Temperature dependent CEST experiments were carried out in the 25 to 50 °C range in buffered solutions for the [Co(L1)]2+, [Ni(L1)]2+, [Fe(L2)]2+ and [Co(L2)]2+ complexes as the most promising paraCEST agents. As shown in Figures 2A–B, S6, and S7, the position of the CEST peak changes with temperature. All of the CEST peaks shift closer to the bulk water signal as temperature increases. The slopes of the lines obtained from a plot of frequency offset as a function of temperature give rise to CT values in the range of −0.12 to −0.56 ppm/°C (Table 3) at 11.7 T. As anticipated, lower CT values were associated with less highly shifted exchangeable protons, while larger CT values corresponded to protons with large hyperfine shifts.[17] The furthest shifted non-exchangeable proton resonances for [Co(L1)]2+ give values of −0.68 and −0.53 ppm/°C (Figure S7b). Negative values show that there is a shift towards less positive CEST peak position with increase in temperature.

As shown in Figures 2a–b, S6, and S8, the intensity of the CEST peak of each complex increases as temperature increases. This increase in intensity with temperature corresponds to an increase in rate constants for amide proton exchange as a function of temperature. As shown in Table S1, rate constants for the NH proton exchange in [Fe(L2)]2+ increase monotonically from 240 s−1 at 25 °C to 1020 s−1 at 60 °C. Interestingly, the [Co(L1)]2+ complex shows a different temperature dependent change in CEST intensity for each of the four peaks (Figure S8). The increase in intensity of all peaks is linear over the range of 25–40 °C, but departs slightly from linearity at 50 °C for the two broadest peaks (Figure S7), presumably due to exchange broadening. In contrast, the CEST peaks at 112 ppm and 54 ppm (37 °C) do not broaden appreciably as a function of temperature up to 50 °C.

The complexes [Fe(L2)]2+, [Co(L2)]2+, [Ni(L1)]2+, [Co(L1)]2+ were incubated in rabbit serum and their CEST spectra were recorded (Figure 2C–2F). The CEST peak intensity and position was relatively unchanged in appearance in serum in comparison to that in buffered aqueous solution.[18] These results support the kinetic inertness of the complexes in biological media.

CEST MRI phantoms

CEST imaging data were collected for the most promising paraCEST agent, [Co(L1)]2+, in 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 at 37 °C on a 4.7 T MRI scanner. The two most highly shifted CEST peaks were studied. The peak at 112 ppm gave the largest CEST effect (8.3%) in comparison to the peak at 95 ppm (5.0%) at 37 °C, pH 7.4. The CEST effect was of similar magnitude in blood serum (8.4% and 2.9% for 112 ppm and 95 ppm respectively).

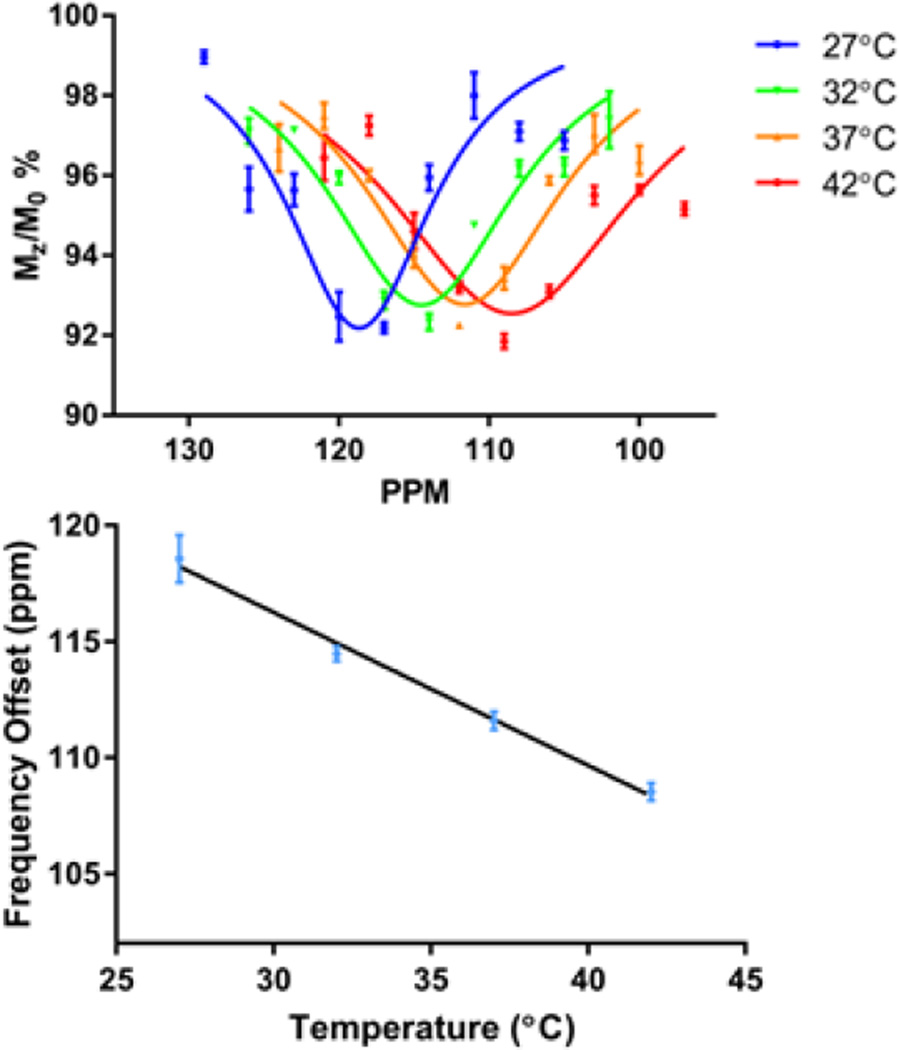

The CEST effect of [Co(L1)]2+ was also measured as a function of temperature on the 4.7 T MRI scanner (Fig 3). These experiments showed that the CEST peak shifted towards the bulk water resonance with increasing temperature. A plot of the frequency of the center of the CEST peak versus temperature gave a linear relationship with a CT value of −0.66 for [Co(L1)]2+. Notably, the intensity of the CEST peak did not increase substantially with temperature, unlike the trend observed at 11.7 T. This is consistent with greater broadening of the CEST peaks at the higher temperatures at the lower field strength of the MRI scanner.

Figure 3.

[Co(L1)]2+ CEST imaging on 4.7 T MRI scanner in 20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl over a temperature range of 27 to 42 °C (left). The frequency offset of peak CEST showed excellent linearity with temperature (right). Linear regression revealed a temperature dependence of the furthest shift CEST peak of −0.659 ppm/°C (R2 = 0.99)

Discussion

Molecular structures

The coordination number of the complexes studied here ranges from six to eight for the various metal ions and tetraazamacrocycles. The [Co(L1)]2+ and [Ni(L1)]2+ cations feature six-coordinate complexes that have the metal ion bound within the cavity of the 14-membered macrocycle and have two carbonyl oxygens of the 1-,4-amide pendent arms bound in trans-configuration.[19] Two amide pendents are not coordinated to the metal ion. In both complexes, the cyclam ring adopts the commonly observed trans-II conformation. Although there are not many examples, the observed coordination geometry is similar to that in the literature for first row transition metal ion complexes of cyclam with pendent groups. For example, a related structure shows a six coordinate NiII bound to 1,4,8,11-tetrakis(2-carbamoylethyl)-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane, which has the 1,4- pendent amide groups bound, similar to that observed here but with six-membered chelate rings for the pendent amide groups.[20] Other related macrocycles with 1,4-carboxymethyl pendents bind the metal ion in a trans-configuration for CoIII, CuII or in a cis-configuration for CrIII.[21]

FeII and CoII complexes of L2 have the metal ion bound above the cavity formed by the macrocyclic amines. This gives six-, seven- or eight- coordinate complexes depending on the number of pendents bound to the metal ion. All four pendent amide groups of L2 bind to FeII. The crystal structure of [Fe(L2)]X2•H2O (X = Cl, Br) is remarkably similar to that of [Mn(L2)]Cl2•2H2O. Both feature eight-coordinate complexes with a C2/c plane of symmetry in the crystal which gives rise to two identical M-O and two M-N bonds. Both complexes have square antiprismatic geometry with a twist angle of 28° and 23° between the planes for the FeII and MnII complexes, respectively. Both structures have the macrocycle backbone in the λλλλ configuration and the pendents in the Λ configuration. As anticipated, the Fe-N bond lengths in [Fe(L2)]2+ are 2.36–2.37 Å, slightly shorter than those in the MnII analog. Cases of eight coordinate FeII complexes appear to more rare than those of MnII, however. An FeII complex of cyclen with four pyridine pendent groups (1,4,7,10-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane)[22] has four different Fe-N bond lengths.[22] Two 2-pyridylmethyl pendent arms have Fe-N distances of 3.108(5) and 2.998(5) Å, while the other two have Fe-N distances of 2.226(4) and 2.233(6) Å which are typical bond lengths. The same ligand forms a regular eight coordinate complex with MnII. An additional relevant example is the FeII complex of 1,4,7,10-tetrakis(2-hydroxypropyl)-1,4,7,10 tetraazacyclododecane. This complex has a 1H NMR spectrum which is consistent with C4 symmetry and coordination of all pendents in aqueous solution.[7a] Thus, sterically efficient pendent groups such as amides or hydroxyethyl groups produce eight coordinate FeII, while bulkier heterocyclic groups give lower coordination numbers.

The seven coordinate complex cation of [Co(L2–7)]X2•CH3OH features an irregular coordination geometry with one of the pendent groups unbound. This complex is remarkably similar to that of a MnII complex of a cyclen macrocycle with three amide pendents.[23] Both complexes are best described as capped trigonal prismatic structures with the capping nitrogen in the macrocycle being the one lacking the coordinating pendent group. The smaller size of the CoII ion in comparison to FeII or MnII is consistent with the lower coordination number of seven.

The trend towards a decrease in coordination geometry with metal ionic radius is continued for the NiII complex and is also observed for a second CoII complex of L2. [Ni(L2)]Cl2∙4H2O and [Co(L2–6)]X2 •3H2O both have only two coordinated pendent amide groups.[24] Both complexes have a distorted octahedral geometry, where the 1-, 7- oxygens of the amide pendent group and four nitrogen donor atoms of the macrocycle encapsulate the metal ion.[24] An analogous NiII-based tetraazamacrocycle with four pendent acetates has octahedral geometry with two carboxylic groups and four macrocyclic nitrogens coordinating to the metal center.[25]

NMR and CEST spectra

The very different appearance of the proton NMR and CEST spectra for the complexes is attributed to differences in structure and dynamics of the complexes. The solution 1H NMR spectra of [Fe(L1)]2+ and [Co(L1)]2+ are consistent with the asymmetric structure of the complexes being retained in solution. The two 1,4-pendents are bound to the metal ions to give 24 distinct proton resonances. The relatively narrow proton resonances show that the complexes are relatively rigid in solution. In contrast, the 1H NMR spectra of complexes of L2 are all quite broad. [Fe(L2)]2+ has six non-exchangeable proton resonances of roughly equal intensity.[7a] These peaks sharpen somewhat upon cooling the complex in d3-acetonitrile, suggesting that there are dynamic processes. The presence of six distinct proton resonances is consistent with the local C4 symmetry found in the crystal structure and a single diastereomeric form of the twisted square antiprism in solution. A single diastereomer would produce four macrocyclic proton resonances and two resonances for the pendent group. Interconversion with a second diastereomer would broaden the proton resonances. The [Co(L2)]2+ complex has a proton spectrum which has extremely broad overlapping resonances, most likely also due to dynamic processes in solution.[2e] Dynamic processes might involve macrocycle backbone ring flip or exchange of the bound and unbound pendent groups.

Incubation of the complexes of FeII and CoII complexes of L2 and the CoII and NiII complexes of L1 in carbonate and phosphate buffer show that they are less reactive compared to other amide-appended transition metal based paraCEST agents, especially those of the mixed aza- and oxa-macrocycles.[9] This is attributed to the encapsulation of the divalent metal ion by the L2 or L1 macrocycle that may protect the metal ion from binding of anions or displacement by acid. In addition, it is noteworthy that the amide pendents in [Fe(L2)]2+ and [Co(L2)]2+ stabilize the divalent state and prevent oxidation as evidenced by their resistance towards oxidation in air. The CoII and NiII complexes of L1 are also stable towards reaction with anions, cations and acid.

The CEST peaks of the complexes presented here are attributed to amide NH protons. This assignment is based on the lack of water ligands or other exchangeable groups, and the pH dependence of the CEST effect which is characteristic of amide proton exchange.[2c, e, 9] The number of CEST peaks corresponds to the number of inequivalent amide protons which have exchange rate constants suitable for CEST and are shifted sufficiently far from the bulk water peak to be resolved. Notably, the two inequivalent protons on a single amide pendent give rise to resonances that are separated by a 50–70 ppm chemical shift difference. Thus if one resonance falls at 50 to 70 ppm, it likely that one amide proton is buried under the water peak. Several reported amide complexes of NiII, CoII and FeII show two CEST peaks for amide protons with the less shifted peak almost overlapping with water.[2b, d, e]

The lack of symmetry of the FeII, CoII and NiII complexes of L1 as shown in the crystal structures and 1H NMR spectra suggest that as many as four paramagnetically shifted amide NH protons and four CEST peaks may be observed. The actual number of CEST peaks varies from four for [Co(L1)], two for [Fe(L1)]2+ and a single peak for [Ni(L1)]2+. The four intense CEST peaks of the [Co(L1)]2+ complex are shifted 45, 54, 95 and 112 ppm away from the bulk water signal. [Fe(L1)]2+ has two CEST peaks shifted 64 and 78 ppm from bulk water. The remaining two CEST peaks of the FeII complex may be buried under the water proton signal due to their close proximity to the bulk water resonance. Surprisingly, [Ni(L1)]2+ shows a single broad CEST peak at 76 ppm. At this juncture, it is unclear whether this is due to overlapping of CEST peaks or to a change in geometry of the complex in solution in comparison to the solid state. Unfortunately, the 1H NMR spectrum is too broad to give useful information about the solution geometry of the complex.

[Fe(L2)]2+ gives rise to only one CEST peak shifted 50 ppm away from bulk water which presumably represents one set of four equivalent NH protons. The peaks for the other four NH protons are most likely close to the water signal and either not resolved from the water peak or exchanging too rapidly to give a CEST peak. [Co(L2)]2+ also has one CEST peak, which is fewer than anticipated given the lack of symmetry in the molecule as shown in the solid state structures. Unfortunately, the broad nature of the 1H NMR spectrum of the complex makes it difficult to obtain information on the solution geometry of the complex. A single CEST peak is consistent with a six-coordinate complex with pseudo-C2 symmetry and two pendent amides coordinated. In this case, one set of amide CEST peaks would be masked by the water signal. Alternatively, all amide pendent groups may be bound to the metal center in a dynamic equilibrium.[2d, e] [Ni(L2)]2+ similarly demonstrates a single CEST peak which corresponds to the coordination of two pendent amide groups to give a C2 symmetric complex.

The most promising paraCEST agents were studied in rabbit serum, including [Co(L1)]2+, [Ni(L1)]2+, [Fe(L2)]2+ and [Co(L2)]2+. The similarity of the CEST NMR spectra at 11.7 T with that in buffered aqueous solution[2b, e, 7a] suggests that there is no apparent interaction between components of rabbit serum and the paraCEST agents. In contrast, previous studies showed that a NiII -based paraCEST agent reacted with the albumin in blood serum.[9] The most highly shifted CEST peak of [Co(L1)]2+ at 112 ppm gave a similar CEST effect in buffered solution versus blood serum at 4.7 T on a MRI scanner.

Thermometry

The CEST peak positions for the complexes reported here give moderate CT values ranging from −0.56 to −0.33 ppm/°C at 11.7 T for the L1 complexes. At 4.7 T, the furthest shifted CEST peak of [Co(L1)]2+ gives a CT value of −0.66 ppm/°C. This value is 60-fold larger than that of bulk water, used in proton resonance frequency temperature mapping.[13b],[13a] Complexes of L2 have lower CT values in the range of −0.12 or −0.15 ppm/ °C. The smaller values for L2 complexes in comparison to L1 complexes are consistent with the observation that exchangeable protons further shifted from bulk water experience larger temperature sensitivities.[17] The negative CT values here correspond to a shift of the CEST peak to less positive values with increasing temperature.

The change in the CEST peak position is linear over the temperature range of 25 to 50 °C for all complexes studied at 11.7 T. There is little line-broadening of any of the CEST peaks in this temperature range. An absence of line-broadening is desirable to maintain CEST peak intensity at increasing temperature because highly broadened proton resonances are more challenging to saturate in the CEST experiment. Interestingly, the two most highly shifted CEST peaks for [Co(L1)]2+ at 112 and 95 ppm arise from amide protons that have rate constants for proton exchange which are nearly two-fold different (300 ± 40, 540 ± 10 s−1).[26] The more rapidly exchanging proton at 95 ppm has a slight decrease in the CEST peak intensity at the very highest temperature studied (50 °C), consistent with the onset of exchange broadening for this proton. In the absence of peak broadening, the CEST effect increases in intensity with temperature at 11.7 T, suggesting that the detection limit of the paraCEST agent would improve with temperature. Notably, an increase in pH also typically increases the rate constant for proton exchange and this may affect both the intensity of the CEST peak and the temperature at which it broadens. However, a change in pH does not produce a shift in the CEST peak position, unless there is a ligand ionization that affects the coordination sphere or there is loss of the slow exchange condition.[5a, 27]

As field strength decreases, it is more challenging to avoid broadening of the CEST peak with temperature. Notably, the width of the CEST peak of [Co(L1)]2+ at 4.7 T increases with temperature but not at the higher field strength of 11.7 T. Thus even the highly shifted amide proton resonances are exchanging sufficiently fast at high temperatures to affect CEST peak broadening. In comparison, the water protons of EuIII-DOTAM-Gly-Phe exchange sufficiently rapidly at temperatures greater than 40 °C, at neutral pH to lead to substantial exchange broadening of the CEST peak.[14a] This is typical of EuIII paraCEST agents that produce the CEST effect through water proton exchange because rate constants tend to be large (>1000 s−1). Interestingly, a TmIII complex of DOTAM shows CEST peaks attributed to amide NH protons, one of which has a temperature dependence of 0.57 ppm/°C. This CEST peak does not change linewidth with temperature, highlighting the promise in development of amide proton paraCEST agents for thermometry.[14b]

Finally, an alternative method for monitoring temperature is to use the non-exchangeable paramagnetically shifted proton resonances (paraSHIFT) through magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) as demonstrated for several Ln(III) complexes[28]. Using paraSHIFT agents requires the acquisition of a full spectrum on the MRI scanner and needs somewhat higher concentrations for in vivo studies in comparison to paraCEST agents.[27,28] The amide appended-complexes studied here however, with the exception of [Co(L1)]2+, are not suitable as paraSHIFT agents because their non-exchangeable macrocyclic protons are broadened due to dynamic processes. Studies of Co(II) and Fe(II) complexes containing rigid aromatic pendent groups[2c,d, 8] that produce suitable NMR spectra for paraSHIFT applications are underway.

Conclusion

The crystal structures shown here are highly informative for understanding the solution spectroscopy and CEST effects of tetraazamacrocyclic complexes of FeII, CoII and NiII that contain amide pendents. The variation in coordination number from 6 to 8 produces different symmetries of the complexes that give rise to distinct CEST spectra. Complexes of L1 in particular have highly shifted and relatively narrow CEST peaks that are favorable for imaging. The [Co(L1)]2+ complex has two highly shifted CEST peaks that give large temperature dependencies and maintain CEST peak intensity even at >50 °C. Preliminary studies towards in vivo work show that several of the complexes are inert in blood serum under physiologically relevant conditions.

Experimental Section

General

CEST spectra were acquired on a Varian Inova 500 MHz NMR (11.7 T) spectrometer and processed by using ACD NMR processor software, mass spectral data were acquired on a Thermo Finnigan LCQ Advantage Ion Trap LC/MS equipped with a Surveyor HPLC system. An Orion 8115BNUWP Ross Ultra Semi Micro pH electrode connected to a 702 SM Titrion pH meter was used for all pH measurements. Rabbit serum was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Complexes of L1 and L2 were prepared by following previously described procedures.[2b, e, 7a]

Synthetic procedures

[Fe(L1)](CF3SO3)2

Ligand L1 (18.4mg, 0.0429 mmol) and Fe(CF3SO3)2 (15.2 mg, 0.0429 mmol) were added to a round bottom flask and stirred in acetonitrile at 50°C for 24 hours under argon. A sticky amorphous brown solid was collected. Yield: 29.8 mg, 0.0381 mmol, 88.8%. 1H NMR(500MHz, [D3]Acetonitrile, 25°C): δ=236, 218, 216, 208, 144, 123, 99, 97, 94, 90, 85, 72, 69, 65, 60, 51, 26, 24, 20, 14, 7, −2, −15, −19, −20, −34, −37; ESI-MS: m/z(%): 242.2 (100) [M/2]2+.

[Ni(L2)](CF3SO3)2

Ligand L2 (81.9 mg, 0.204 mmol) and Ni(CF3SO3)2 (74.8 mg, 0.210 mmol) was added to a round bottom flask and stirred in acetonitrile at 70°C for 24 hours. The mixture was centrifuged and a yellow liquid was carefully decanted from a purple solid. The purple solid was dried under vacuum. Yield: 91.9 mg, 0.131 mmol, 64.2%. %. 1H NMR(500MHz, [D6]DMSO, 25°C): δ= 141, 109, 75, 64, 45, 17,11; 1H NMR(500MHz, D2O, 25°C): δ=140, 111, 63, 48,15; ESI-MS: m/z: 229.4, 230.3 [M/2]2+, 457.3 [M-H]+, 607.0 [M+(CF3SO3)]+.

CEST NMR spectroscopy

Application of a presaturation pulse of 24 µT (1000 Hz) for 2 seconds over the range +140 ppm to −140 ppm was used to generate CEST spectral data. The percent reduction of the water signal was monitored over 1 ppm increments and plotted against the frequency offset to give a CEST spectrum. CEST experiments were performed over a temperature range of 25–50 °C. Samples contained 10 mM complex, 20 mM HEPES, and 100 mM NaCl in rabbit serum. Samples were placed in a NMR insert, while the outer NMR tube contained d6-DMSO.

The Omega plot method was used to determine proton exchange rate constants (kex).[18] Presaturation pulse power was varied over the range of 8–24 µT and the presaturation pulse was applied to the magnetization on-resonance (Mz) and off-resonance (Mo) for 4 seconds. Data obtained from the plot of the Mz/Mo-Mz versus 1/ω12 (ω1 in rad/s), where the x-intercept (−1/kex), was fit by linear regression to calculate proton exchange rates. Samples contained 10 mM complexes in rabbit serum or 10 mM complex, 20 mM HEPES and 100 mM NaCl.

CEST MRI

CEST MR images were acquired with triplicate samples of Co(L1)]2+ on a 4.7 Tesla preclinical MRI using a 35 mm transceiver coil (ParaVision 4.0, Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA). CEST imaging data was acquired using a steady-state, free precession protocol (SSFP) with a pre-saturation pulse train comprised of three Gauss pulses (12 µT for 1 second each, interpulse delay of 200 µs). The offset frequency of the saturation pulse was alternated between on resonance (Mz) and off resonance (M0) frequencies symmetrically distributed on either side of the bulk water resonance. The SSFP acquisition parameters were: TE/TR = 1.6/3.2 ms, FOV = 3.2×3.2 cm, acquisition matrix of 128×128, slice thickness = 1.5 mm, flip angle = 60, NEX =2, evolutions = 10. To maintain optimal CEST contrast, a centric-encoding scheme was employed with 5 dummy scans to establish the steady-state condition. Images were acquired over a total of 9 frequency offsets for each temperature for [Co(L1)]2+ furthest shifted peak (112 ppm at 37°C).

Image processing was carried out using in-house software algorithms developed in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA). Prior to normalization, the 10 evolution images were averaged to improve signal-to-noise ratios. All images were then normalized to the mean intensity of a buffer/salt phantom. CEST values were determined as the ratio of signal from the on-resonance scans (Mz) and off-resonance scans (M0). To determine the offset frequency of peak CEST as a function of temperature, the CEST values (Mz/M0) were plotted against the on-resonance ppm and fit to a Lorentzian curve in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

X-ray Diffraction Data

The vapor diffusion method was used for crystallization of these complexes. Complexes were dissolved in a small vial in methanol which was placed in a larger vial containing hexanes. Single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were selected and mounted on glass capillary on a Bruker SMART APEX2 CCD diffractometer installed at a rotating anode source (Mo Kα, λ = 0.71073 Å). The crystals were cooled to 90(2) K during data collection using an Oxford Cryosystems (Cryostream 700) nitrogen gas-flow apparatus. The data were collected by the rotation method with a 0.5° frame width (ω scan) and a 5, 120, 5, 30, and 15 second exposure time per frame, respectively. Five sets of data, with 360 frames in each set, were collected for each crystal, nominally covering complete reciprocal space.

Using the Olex2 crystal structure analysis program[29], the structures were solved with the olex2.solve structure solution program using the Charge Flipping method and were refined with the SHELXL refinement package using Least-Squares minimization.[30]

In the crystal structure of [Co(L1)]Cl2•H2O•CH3OH, the oxygen atom in one methanol molecule is disordered over two positions. A solvent mask (OLEX2) was applied to the structure which masks a heavily disordered region which contains approximately 32 e−/Å3 which is likely due to disordered methanol and water molecules. The Uij thermal parameters of the atoms O1 & O2, C12 & C14, C13 & C15, and O5 & O5A were pairwise constrained using EADP. Also the bond lengths of both O5 and O5A to C19 were constrained to be the same using SADI. In the structure of [Co(L2–7)]X2•CH3OH, the macrocycle ring exhibits a two-fold disorder. The occupancies of the two disordered parts were constrained to sum to 1. The Uij thermal parameters of each atom which is disordered was constrained to match that of its disordered counterpart. In [Co(L2–6)]X2•3H2O, [Co(L2–7)]X2•CH3OH, and [Fe(L2)]X2•H2O there exists a disorder of the counter ions wherein bromine atoms are substituted for the chlorine atoms. The occupancies of the two disordered atoms were constrained to sum to 1. This disorder was modeled in the cobalt structures without constraints or restraints, while for the iron complex, the atoms Cl1 and Br1 were constrained to have the same Uij thermal parameters as well as the same xyz coordinates using EADP and EXYZ, respectively. [Ni(L1)](CF3SO3)2•H2O exhibits a partial disorder of the macrocycle, which is modeled without constraint.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

JRM thanks the NSF (CHE-1310374) for support. JAS thanks Roswell Park's NCI Support Grant (P30CA16056) and the Roswell Park Alliance Foundation (JAS) and the NIH (R03CA175858) for funding.

Footnotes

Associated Content

Supporting Information: Methods, NMR spectra, phantom images, additional crystal structures and CEST spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.a) Lauffer RB. Chem. Rev. 1987;87:901–927. [Google Scholar]; b) Richardson N, Davies JA, Raduchel B. Polyhedron. 1999;18:2457–2482. [Google Scholar]; c) Gaughan TMFGT, Hagen J, Wedeking PW, Sibley P, Wilson LJ, Lee DW. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1988;15:31–36. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(88)90157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Drahos B, Lukes I, Toth E. Eur. J. Chem. 2012:1975–1986. [Google Scholar]; e) Gale EM, Mukherjee S, Liu C, Loving GS, Caravan P. Inorg Chem. 2014;53:10748–10761. doi: 10.1021/ic502005u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Tsitovich PB, Spernyak JA, Morrow JR. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:13997–14000. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Olatunde AO, Dorazio SJ, Spernyak JA, Morrow JR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012 doi: 10.1021/ja307909x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Dorazio SJ, Tsitovich PB, Siters KE, Spernyak JA, Morrow JR. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:14154–14156. doi: 10.1021/ja204297z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Dorazio S, Olatunde A, Tsitovich P, Morrow J. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2013:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00775-013-1059-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Dorazio SJ, Olatunde AO, Spernyak JA, Morrow JR. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:10025–10027. doi: 10.1039/c3cc45000g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) van Zijl PC, Yadav NN. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65:927–948. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Vinogradov E, Sherry AD, Lenkinski RE. J. Magn. Reson. 2013;229:155–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Viswanathan S, Kovacs Z, Green KN, Ratnakar SJ, Sherry AD. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:2960–3018. doi: 10.1021/cr900284a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Terreno E, Castelli DD, Aime S. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2010;5:78–98. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) McVicar N, Li AX, Suchy M, Hudson RH, Menon RS, Bartha R. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70:1016–1025. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ali MM, Liu G, Shah T, Flask CA, Pagel MD. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:915–924. doi: 10.1021/ar8002738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Bertini I, Luchinat C, Parigi G, Pierattelli R. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:1536–1549. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wicholas ML, Drago RS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969;91:5963–5970. [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Dorazio SJ, Morrow JR. Inorg. Chem. 2012;51:7448–7450. doi: 10.1021/ic301001u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tsitovich PB, Burns PJ, McKay AM, Morrow JR. J Inorg Biochem. 2014;133:143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsitovich PB, Morrow JR. Inorg Chim Acta. 2012;393:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olatunde AO, Cox JM, Daddario MD, Spernyak JA, Benedict JB, Morrow JR. Inorg Chem. 2014 doi: 10.1021/ic5006083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorazio SJ, Tsitovich PB, Gardina SA, Morrow JR. J Inorg Biochem. 2012;117:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters JA, Huskens J, Raber DJ. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 1996;28:283–350. [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Zhang S, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17572–17573. doi: 10.1021/ja053799t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Li AX, Wojciechowski F, Suchy M, Jones CK, Hudson RH, Menon RS, Bartha R. Magn. Reson. Med. 2008;59:374–381. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Stevens TK, Milne M, Elmehriki AA, Suchy M, Bartha R, Hudson RH. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2013;8:289–292. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Ehses P, Fidler F, Nordbeck P, Pracht ED, Warmuth M, Jakob PM, Bauer WR. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:457–461. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wlodarczyk W, Boroschewski R, Hentschel M, Wust P, Monich G, Felix R. J Magn Res Imag. 1998;8:165–174. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880080129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Li AX, Wojciechowski F, Suchy M, Jones CK, Hudson RH, Menon RS, Bartha R. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:374–381. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Stevens TK, Milne M, Elmehriki AA, Suchy M, Bartha R, Hudson RH. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2013;8:289–292. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhang S, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17572–17573. doi: 10.1021/ja053799t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park JG, Jeon Ie R, Harris TD. Inorg Chem. 2015;54:359–369. doi: 10.1021/ic5025586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertini I, Turano P, Vila AJ. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:2833–2932. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertini I, Luchinat C. NMR of Paramagnetic Molecules in Biological Systems. Ann Arbor: Benjamin/Cummings; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dixon WT, Ren J, Lubag AJM, Ratnakar J, Vinogradov E, Hancu I, Lenkinski RE, Sherry AD. Magn. Reson. Med. 2010;63:625–632. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boeyens JCA, Cook L, Duckworth PA, Rahardjo SB, Taylor MR, Wainwright KP. Inorg Chim Acta. 1996;246:321–329. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freeman GM, Barefield EK, Vanderveer DG. Inorg Chem. 1984;23:3092–3103. [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Tonei DM, Ware DC, Brothers PJ, Plieger PG, Clark GR. Dalton Trans. 2006:152–158. doi: 10.1039/b512798j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ware DC, Tonei DM, Baker L-J, Brothers PJ, Clark GR. Chem. Commun. 1996:1303–1304. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu S-L, Liu H, Zhu H-P, Liu Q-T. Plyhedron. 2000;19:431–435. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang S, Westmoreland TD. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:719–727. doi: 10.1021/ic8003068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagata MK. B.A. thesis. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University; 2013. p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riesen A, Zehnder M, Kaden TA. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1986;69:2067–2073. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dorazio SJ, Bruckner C. J Chem Ed. 2015;92:1121–1124. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rancan G, Delli Castelli D, Aime S. Magn Reson Med. 2015 doi: 10.1002/mrm.25589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.a) Pakin SK, Hekmatyar SK, Hopewell P, Babsky A, Bansal N. NMR Biomed. 2006;19:116–124. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Coman D, Trubel HK, Rycyna RE, Hyder F. NMR Biomed. 2009;22:229–239. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dolomanov OV, Bourhis LJ, Gildea RJ, Howard JAK, Puschmann H. J Appl Crystallogr. 2009;42:339–341. doi: 10.1107/S0021889811041161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheldrick GM. Acta Cryst Sect A. 2008;64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.