Abstract

Background

China has the largest population of smokers in the world, yet the quit rate is low. We used data from the 2010 Global Adult Tobacco Survey China to identify factors influencing quit attempts among male Chinese daily smokers.

Methods

The study sample included 3303 male daily smokers. To determine the factors that were significantly associated with making a quit attempt, we conducted logistic regression analyses. In addition, mediation anal yses were carried out to investigate how the intermediate association among demographics (age, education, urbanicity) and smoking related variables affected making a quit attempt.

Results

An estimated 11.0% of male daily smokers tried to quit smoking in the 12 months prior to the survey. Logistic regression analysis indicated that younger age (15–24 years), being advised to quit by a health care provider (HCP) in the past 12 months, lower cigarette cost per pack, monthly or less frequent exposure to smoking at home, and awareness of the harms of tobacco use were significantly associated with making a quit attempt. Additional mediation analyses showed that having knowledge of the harm of tobacco, exposure to smoking at home, and having been advised to quit by an HCP were mediators of making a quit attempt for other independent variables.

Conclusion

Evidence-based tobacco control measures such as conducting educational campaigns on the harms of tobacco use, establishing smoke-free policies at home, and integrating tobacco cessation advice into primary health care services can increase quit attempts and reduce smoking among male Chinese daily smokers.

Keywords: China, Global Adult Tobacco Survey, Smoking, Quit attempt

Introduction

Smoking is the single most preventable cause of premature death worldwide (World Health Organization, 2011), and the health burden imposed by smoking is particularly great in low- and middle-income countries (Mathers and Loncar). China has the largest population of smokers in the world (Li et al., 2011a). The number of smoking related deaths in China was estimated at about 1 million in 2014, and more than 50 million smoking-related deaths are projected to occur from 2012 to 2050 (Levy et al., 2014). Moreover, in addition to exacting a terrible toll in mortality and morbidity, tobacco use has dire economic consequences. In China, the estimated financial cost (in US dollars) attributable to tobacco use quadrupled in just 8 years, from $7.2 billion in 2000 to $28.9 billion in 2008 (Eriksen et al., 2012).

Persuading current smokers to quit is a critical component of tobacco control efforts internationally. Smokers who quit smoking by age 40 reduce their risk of dying early from smoking-related diseases by more than 90% (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Unfortunately, the smoking prevalence among males in China is very high (estimated at 52.9% in 2010) (Giovino et al., 2012). This dire situation is compounded by the low quit ratio among Chinese male smokers, which was 12.6% in 2010 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

Understanding the determinants of smoking cessation is important for choosing interventions that might help smokers to quit. Research has shown that lower nicotine dependency and awareness of tobacco's harm to health are predictors of making a quit attempt (Hagimoto et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2009; Hellman et al., 1991; Borland et al., 2010). Data on the association between education level and quit attempts have been mixed (Zhou et al., 2009; Hellman et al., 1991; Borland et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010, 2011b). The literature is also inconclusive on the impact of age on quit attempts; some studies have suggested that older smokers are more likely to make quit attempts (Li et al., 2010, 2011b), while others have found they are less likely to do so (Borland et al., 2010).

In this study, we used data from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) China to determine factors that were associated with quit attempts among male daily smokers in China.

Methods

Sample

GATS China, a nationally representative household survey of adults aged ≥15 years, was conducted during 2009 through 2010 using a multistage stratified cluster sample design. Details of the GATS methodology have been reported previously (Hsia et al., 2010). In all, 13,354 adults completed interviews, including 6603 males and 6751 females. The overall response rate was 96.0%. The present study focused on quit attempts among daily cigarette smokers, defined as adults who reported smoking every day at the time of the survey. Female smokers were not included because of their relatively low smoking prevalence (2.4%) (Li et al., 2011a).

Measures

Dependent variable

Quit attempts

Current cigarette smokers were asked, “During the past 12 months, have you tried to stop smoking?” Response options were “yes,” “no,” or “refused.” Those who refused to answer were coded as “missing” and were excluded from the analysis.

Independent variables

Three demographic variables (age, education, and urbanicity status) were used in the analysis. Age was grouped in four categories: 15–24, 25–44, 45–59, and 60 years or above. Self-reported education levels were classified into four categories: primary school or less, secondary school or less, high school graduate, and college or above. Urbanicity, a measure of how urbanized an area is, was determined by the urban vs rural status of the counties or districts where the respondent resided at the time of the survey.

The seven smoking-related variables included in the analyses were defined as follows:

1) Exposure to smoking at home was defined as how often people smoked inside the respondent's home (daily, weekly, monthly or less, or never). For the analysis, those reporting “never” were aggregated with the group reporting “monthly or less.”

2) Nicotine dependency was defined by how soon daily smokers first smoked after waking up (within 5 minutes, 6–30 minutes, 31–60 minutes, >60 minutes).

3) Exposure to tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship (TAPS) was defined as the frequency with which respondents had noticed advertisements or signs promoting cigarettes through various venues in the past 30 days. The venues include advertisements in stores, on television, on radio, on billboards, on posters or promotion materials, in newspapers or magazines, on the Internet, in cinemas, on public transportation, on public walls, at sporting events, at social events, and from other cigarette promotional activities. Based on self-reports, respondents were grouped as either “through one or less venue” or “through two or more venues.”

4) Awareness of tobacco harms was determined by the number of selected diseases (i.e., stroke, heart attack, and lung cancer) that respondents believed smoking could cause.

5) The cost of a pack of 20 manufactured cigarettes was calculated using the amount paid and the number bought for their last purchase of manufactured cigarettes in the past 30 days. Three cost categories (in Chinese Ren Min Bi [RMB] currency) were constructed: less than 4 RMB per pack; 4–19 RMB per pack; and 20 RMB or more per pack.

6) A wealth index was computed using a series of questions asking respondents whether they owned specific household items (Rutstein, 1999). Owning more items contributed to a higher index score. The index was categorized into three groups: low, medium, and high, with each groups comprising roughly a third of the respondents.

7) To determine advice to quit from a health care provider (HCP), respondents were asked the number of times they had seen an HCP during the past 12 months and whether they were advised to quit smoking by an HCP during the visits. Respondents were placed in one of three groups: (a) did not visit an HCP, (b) visited an HCP but were not advised to quit, and (c) visited an HCP and were advised to quit.

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted using SUDAAN 11.0 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA). Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses were used to assess the association between making at least one quit attempt in the past 12 months and the three demographic variables (age, education, and urbanicity), as well as the other smoking related variables of interest. The multistage cluster sampling design was taken into account to calculate the variance of estimates.

In addition, mediation analyses were conducted on those predictor variables that were not found significant in adjusted logistic regression. Those aimed to explore and understand the potential indirect paths by which independent variables might influence the outcome variables through a mediator. Such mediation analyses might also help further understand the relationships among independent variables. The method and SAS macro described by Hayes were applied for data analyses (Hayes, 2013). A parallel multiple mediator model was adopted. We used the same variable coding used in logistic regression for all variables in the mediation analysis except exposure to TAPS, where the original, ungrouped number of TAPS venues was applied as a mediator, since Hayes' program could not handle dichotomous variables as mediators.

Results

Sample characteristics

In all, 3303 male daily smokers were included in the China GATS 2010 data. The demographic distributions and sample sizes are presented in Table 1. One in nine male daily smokers (11.0%) had made at least 1 attempt to quit smoking in the past 12 months. More than half (56.2%) of the male daily smokers were aged 15–44 years, two-thirds (67.7%) had received a secondary education or less, and 58.0% lived in rural areas. Nearly one-quarter (24.1%) smoked within 5 minutes of waking up. Only 11.8% of the smokers had been exposed to TAPS in two or more venues. Approximately one-fifth (19.9%) were aware that smoking could cause all three of the diseases of interest (lung cancer, heart attack, and stroke), while 24.0% were not aware that smoking could cause any of these diseases. About a one-fifth of the men had visited an HCP but had not been advised to quit, while only 9.8% had visited an HCP and been advised to quit within the past 12 months.

Table 1.

Weighted percentages estimated for male Chinese daily smokers by variables of interest, among male Chinese daily smokers, Global Adult Tobacco Survey—China 2010.

| Variable | Unweighted Sample size |

Weighted Percentage (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15–24 | 136 | 13.4 (10.8–16.4) |

| 25–44 | 1239 | 42.8 (39.4–46.3) | |

| 45–59 | 1202 | 30.4 (28.1–32.9) | |

| ≥60 | 726 | 13.4 (11.8–15.1) | |

| Education | Primary or less | 1107 | 22.3 (18.9–26.1) |

| Secondary or less | 1358 | 45.4 (41.3–49.8) | |

| High school | 553 | 22.8 (19.3–26.9) | |

| College or above | 285 | 9.4 (7.2–12.3) | |

| Urbanicity | Urban | 1225 | 42.0 (31.4–53.3) |

| Rural | 2078 | 58.0 (46.7–68.6) | |

| Wealth index | Low | 1234 | 29.4 (23.9–35.4) |

| Medium | 1061 | 34.4 (30.0–39.0) | |

| High | 1008 | 36.3 (29.3–43.8) | |

| Exposure to smoking at home |

Monthly or less | 300 | 8.7 (7.1–10.7) |

| Weekly | 165 | 7.0 (5.0–9.8) | |

| Daily | 2835 | 84.3 (80.9–87.1) | |

| Time to first smoke after awakening |

60 or more minutes | 938 | 31.9 (28.4–35.6) |

| 30–59 minutes | 522 | 17.8 (15.0–21.0) | |

| 6–29 minutes | 881 | 26.2 (23.5–29.1) | |

| Within 5 minutes | 959 | 24.1 (21.1–27.4) | |

| Number of exposures to TAPS | 1 or fewer | 2993 | 88.2 (84.2–91.3) |

| Two or more | 310 | 11.8 (8.7–15.8) | |

| Awareness of tobacco harms* | 0 | 952 | 24.0 (20.4–27.9) |

| 1 | 1164 | 37.4 (34.5–40.4) | |

| 2 | 561 | 18.8 (15.5–22.5) | |

| 3 | 623 | 19.9 (16.4–23.9) | |

| Cigarette cost per pack | ≥20 RMB | 165 | 7.3 (4.6–11.3) |

| 4–19 RMB | 1741 | 68.1 (63.6–72.4) | |

| <4 RMB | 995 | 24.6 (20.5–29.2) | |

| Advised by a HCP to quit in past 12 months |

Did not visit | 2190 | 71.0 (67.1–74.7) |

| Visited, not advised to quit |

705 | 19.1 (16.0–22.6) | |

| Visited, advised to quit |

406 | 9.8 (8.2–11.8) | |

| Made one or more quit attempts in past 12 months |

Yes | 370 | 11.0 (8.7–13.9) |

| No | 2933 | 89.0 (86.1–91.3) |

CI, confidence interval; HCP, health care practitioner; RMB, Ren Min Bi (Chinese currency); TAPS, tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship.

Number of diseases of interest the smokers thought were caused by smoking (stroke, heart attack, and lung cancer).

Logistic regression

The adjusted logistic regression analysis (Table 2) indicates male daily smokers aged 15–24 were more likely to make attempts to quit when compared with those aged 60 years or older (OR = 2.23,95% CI 1.02–4.89) and those aged 25–44 years (OR = 2.18, 95% CI 1.03–4.60). Male daily smokers who were aware that smoking can cause all three diseases of interest were significantly more likely to make a quit attempt than those who were not aware that smoking can cause any of these diseases (OR = 2.58, 95% CI 1.50–4.43). Even smokers who were aware of the connection with smoking for just one of the diseases were significantly more likely to make a quit attempt than those with no awareness (OR = 2.04, 95% CI 1.41–2.97). Smokers who had visited an HCP in the past 12 months and were advised by an HCP to quit smoking were significantly more likely to make a quit at tempt compared with smokers who had not visited an HCP during that time period (OR = 2.90, 95% CI 1.98–4.23) or those who had visited an HCP but had not been advised to quit (OR = 2.24, 95% CI 1.43–3.51). There was no significant difference in making a quit attempt between smokers who did not visit an HCP and those who visited one but were not advised to quit.

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis of the relationship between selected variables and making a quit attempt* among male Chinese daily smokers, Global Adult Tobacco Survey—China 2010.

| Predictor variable | Coding | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted†

OR (95% CI)‡ |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15–24 | 1 | 1.87 (0.79–4.44) | 2.23 (1.02–4.89)§ | 2.18 (1.03–4.60)§ |

| 25–44 | 2 | 0.94 (0.60–1.46) | 1.03 (0.57–1.85) | 1.00 | |

| 45–59 | 3 | 0.95 (0.71–1.27) | 1.09 (0.71–1.69) | 1.07 (0.71–1.59) | |

| ≥60 | 4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.54–1.74) | |

| Education | Primary or less | 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Secondary or less | 2 | 1.30 (0.84–2.02) | 1.32 (0.85–2.03) | ||

| High school | 3 | 1.12 (0.66–1.90) | 1.32 (0.71–2.45) | ||

| College or above | 4 | 1.36 (0.85–2.20) | 1.73 (0.89–3.36) | ||

| Urbanicity | Urban | 1 | 0.69 (0.45–1.06) | 0.64 (0.37–1.11) | |

| Rural | 2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Wealth index | Low | 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Medium | 2 | 0.77 (0.43–1.39) | 0.77 (0.40–1.49) | ||

| High | 3 | 0.75 (0.49–1.14) | 0.98 (0.52–1.86) | ||

| Exposure to smoking at home | Monthly or less | 1 | 1.54 (0.97–2.46) | 1.82 (1.18–2.81)§ | |

| Weekly | 2 | 1.63 (0.96–2.74) | 1.67 (0.98–2.85) | ||

| Daily | 3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Time to first smoke after awakening | 60 or more minutes | 1 | 1.31 (0.82–2.10) | 1.09 (0.67–1.77) | |

| 30–59 minutes | 2 | 0.99 (0.48–2.02) | 0.86 (0.41–1.81) | ||

| 6–29 minutes | 3 | 1.00 (0.67–1.50) | 0.91 (0.59–1.43) | ||

| Within 5 minutes | 4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Exposures to TAPS | 1 or fewer | 1 | 1.53 (0.82–2.87) | 1.46 (0.78–2.72) | |

| Two or more | 2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Awareness of tobacco harms‡ | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1.89 (1.26–2.85)§ | 2.04 (1.41–2.97)§ | ||

| 2 | 2 | 1.53 (0.96–2.42) | 1.65 (1.00–2.72)§ | ||

| 3 | 3 | 2.47 (1.64–3.71)§ | 2.58 (1.50–4.43)§ | ||

| Cigarette cost per pack | ≥20 RMB | 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.67 (0.30–1.49) |

| 4–19 RMB | 2 | 1.60 (0.77–3.35) | 1.50 (0.67–3.35) | 1.00 | |

| <4 RMB | 3 | 2.17 (1.06–4.45)§ | 2.45 (1.02–5.26)§ | 1.64 (1.01–2.66)§ | |

| Advised by a HCP to quit in past 12 months | Did not visit | 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.77 (0.49–1.19) |

| Visit, not advised | 2 | 1.20 (0.78–1.84) | 1.31 (0.84–2.03) | 1.00 | |

| Visit, advised | 3 | 2.44 (1.63–3.63)§ | 2.90 (1.98–4.23)§ | 2.24 (1.43–3.51)§ |

CI, confidence interval; HCP, health care practitioner; OR, odds ratio; RMB, Ren Min Bi (Chinese currency); TAPS, tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship.

0 = did not make any quit attempt, 1 = made at least one quit attempt.

Adjusted for all other variables in the model.

Statistically significant, p < 0.05.

Number of diseases of interest the smokers thought were caused by smoking (stroke, heart attack, and lung cancer).

The frequency of exposure to smoking at home was also a significant factor. Smokers who were exposed to smoking at home monthly or less often were more likely to have made a quit attempt (OR = 1.80, 95% CI 1.17–2.79) than were those who were exposed on a daily basis. Regarding the cost of cigarettes, smokers who spent less than 4 RMB per pack of cigarettes were more likely to make a quit attempt compared with smokers who spent 20 RMB or more per pack (OR = 2.45, 95% CI 1.02–5.26) or smokers who spent 4–19 RMB per pack (OR = 1.64, 95% CI 1.01–2.51). There was no significant difference in making a quit attempt between those who spent more than 20 RMB per pack and those who spent 4–19 RMB.

Mediation analysis

In the logistic regression analyses, education, urbanicity, wealth index, nicotine dependency, and exposure to TAPS were not significant factors for predicting a quit attempt. A mediation analysis was conducted to evaluate whether the association between these five factors and making a quit attempt were mediated by other independent variables. Urbanicity was not evaluated as a mediator, since changes in other variables could not affect the urban–rural status of the areas people lived.

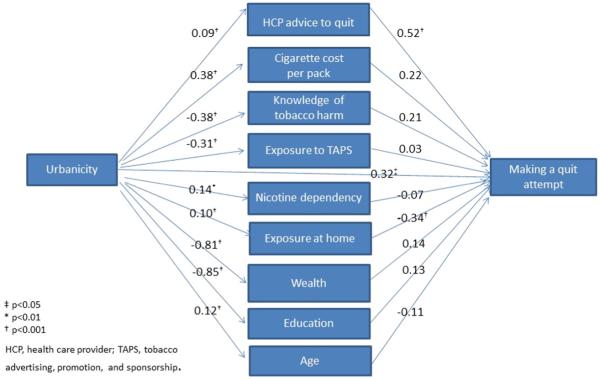

Fig. 1 illustrates the interpretation of the mediation analysis, using the example of urbanicity. Variable coding is the same as in Table 1. The coefficient of regressing education (higher values indicate more education) on urbanicity was −0.85 in step 1, indicating rural residents had lower education levels; the coefficient of regressing making a quit attempt on education (with other variables as controls) was 0.13 in step 2. Thus, the individual indirect effect of urbanicity on making a quit attempt through education was −.85*0.13 = −0.11.

Fig. 1.

Mediation effects of urbanicity on making a quit attempt.

The direct effect was 0.32, representing the effects of urbanicity on making a quit attempt while controlling for all other variables. The individual indirect effects through other variables were calculated similarly and the total indirect effect summed up to −0.24. Hence, the total effect of urbanicity on making a quit attempt was 0.07, the sum of direct and indirect effects. Table 3 shows the individual regression coefficients from the mediation analysis. The direct, indirect, and total effects are summarized in Table 4. A positive coefficient in Table 4 indicates an increase in the likelihood of making a quit attempt when the value of the independent variable increases, and a negative coefficient indicates a decrease when the value of the independent variable increases. The direct effects and indirect effects in Table 4 do not necessarily sum up to the total effects because of different scaling in dichotomous logistics regression.

Table 3.

Results of mediational regression on making a quit attempt among Chinese daily male smokers—Global Adult Tobacco Survey China, 2010.

| Step 1 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator variables (dependent) |

||||||||||

| Variables of interest (independent) |

HCP advice to quit |

Cigarette cost per pack |

Knowledge of tobacco harms |

Exposure to TAPS |

Nicotine dependency |

Smoke exposure at home |

Wealth index |

Urbanicity | Education | Age |

| Education | −0.07* | −0.25* | 0.27* | 0.24* | −0.18* | −0.07* | 0.43* | – | – | −0.26* |

| Urbanicity | 0.09* | 0.38* | −0.38* | −0.31* | 0.14† | 0.10* | −0.81* | – | −0.85* | 0.12* |

| Wealth index | −0.05† | −0.33* | 0.29* | 0.24* | −0.13* | −0.07* | – | – | 0.56* | −0.11* |

| Nicotine dependency | 0.01 | 0.04* | −0.06 | −0.04‡ | – | 0.08* | −0.06 | – | −0.11 | 0.04* |

| Exposure to TAPS | −0.07 | −0.24* | 0.33* | – | −0.15* | −0.06 | 0.43* | – | 0.55* | −0.26* |

| Step 2 |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator variables (independent) |

Outcome |

||||||||||

| Variable of interest | HCP advice to quit |

Cigarette cost per pack |

Knowledge of tobacco harms |

Exposure to TAPS |

Nicotine dependency |

Smoke exposure at home |

Wealth index |

Urbanicity | Education | Age | Making a quit attempt§ |

| Education | 0.53* | 0.24 | 0.21* | 0.03 | −0.07 | −0.33* | 0.07 | – | – | −0.12 | 0.08 |

| Urbanicity | 0.52* | 0.22 | 0.21* | 0.03 | −0.07 | −0.34* | 0.14 | – | 0.13 | −0.11 | 0.32‡ |

| Wealth index | 0.53* | 0.24 | 0.21* | 0.03 | −0.07 | −0.33* | – | – | 0.08 | −0.12 | 0.07 |

| Nicotine dependency | 0.53* | 0.24 | 0.21* | 0.03 | – | −0.33* | 0.07 | – | 0.08 | −0.12 | −0.07 |

| Exposure to TAPS | 0.53* | 0.23 | 0.21* | – | −0.07 | −0.33* | 0.08 | – | 0.09 | −0.12 | −0.02 |

p < 0.001.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.05.

Direct effect of making quit attempt controlling for all other variables. HCP, health care practitioner; TAPS, tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship.

Table 4.

Mediated effects on making a quit attempt—Global Youth Tobacco Survey China, 2010.

| Variables of interest |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Urbanicity | Wealth index |

Nicotine dependency |

Exposure to TAPS |

|

| Coefficient & 95% CI | |||||

| Total effect | 0.15* | 0.07 | 0.13 | −0.12* | 0.08 |

| Direct effect | 0.08 | 0.32* | 0.07 | −0.07 | −0.02 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.07 | −0.24* | 0.05 | −0.04* | 0.12 |

| Individual indirect effect through mediator variables: | |||||

| Age | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| Education | – | −0.11 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.05 |

| Wealth index | 0.03 | −0.11 | – | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| Exposure to smoke at home |

0.02* | −0.03* | 0.02* | −0.03* | 0.02 |

| Nicotine dependency | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | – | 0.01 |

| Exposure to TAPS | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.00 | – |

| Knowledge of tobacco harms |

0.06* | −0.08* | 0.06* | −0.01* | 0.07* |

| Cigarette cost per pack | −0.06 | 0.08 | −0.08 | 0.01 | −0.05 |

| HCP advice to quit | −0.04* | 0.05* | −0.03* | 0.00 | −0.04 |

CI, confidence interval; HCP, health care practitioner; NA, not applicable; TAPS, tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship.

Statistically significant, p < 0.05.

The summary results of the mediation analysis are found in Table 4. Exposure to smoking at home was a significant mediator for education, urbanicity, wealth index, and nicotine dependency on making a quit attempt among male smokers. Knowledge of tobacco harms was a significant mediator for education, urbanicity, wealth index, and nicotine dependency and exposure to TAPS. An HCP's advice to quit was a significant mediator for education, urbanicity, and wealth index.

Rural smokers were more likely than urban smokers to make a quit attempt, controlling for other variables (direct effect =0.32). They were significantly less likely to make a quit attempt because of not having as much awareness of tobacco harms (−0.08) or having more exposure to smoking at home (−0.03), but were significantly more likely to make a quit attempt if they had received advice to quit from an HCP (0.05). The overall or total effects (0.07), however, were not significant.

The direct effect of education on making a quit attempt (0.15) was not significant, but the total effect was significant. Among male smokers, as education levels increased, they were more likely to make a quit attempt because of possessing either greater knowledge of tobacco's harms or less exposure to smoking at home; additionally, they were less likely to make a quit attempt because they had received less quit advice from the HCP. The total indirect effects for education (0.07) were not significant.

The total effect (−0.12) and total indirect effects (−0.04) of nicotine dependency, measured by time to first smoke after waking up, were significant. Less nicotine dependency, or a longer time to first smoke after waking up, was associated with a higher likelihood of a quit attempt because of having more knowledge of tobacco harms and less exposure to smoking at home.

Discussion

The findings from this study suggest that Chinese male daily smokers who were aged 15–24 years had less exposure to smoking at home, had more knowledge of the harms caused by tobacco, spent less on cigarettes, received advice to quit from an HCP, or were more likely than their counterparts to have made at least one quit attempt during the past 12 months. No association was observed between education level and nicotine dependency, and making a quit attempt. However, the mediation analyses suggested that their effects could be mediated by exposure to smoking at home, knowledge of harms caused by tobacco use, and HCP advice to quit (for education level only).

Many of the young smokers aged 15–24 may still be experimenting with smoking, thus were less addicted and more likely to quit, particularly those aged 15–17, who were counted as adults in the GATS survey and included in the current study. The fact that Chinese male smokers initiated daily smoking quite late in life (20.9 years of age) further enhanced this effect. All these could partially explain our observation that smokers aged 15–25 were more likely to make a quit attempt than older smokers.

The current study found that male daily smokers in China who spent less than 4 RMB per pack were twice as likely to make a quit attempt as those who spent 20 RMB or more per pack and were 1.6 times as likely as those who spent 4–19 RMB per pack. The price of cigarettes varies widely in China, with a possible range from 1.5 RMB to more than 150 RMB per pack (Tobacco market of China), a distribution that contrasts sharply with many other countries, where price ranges are narrow across brands. This wide price range in China enables smokers to buy cigarettes at many different price points (White et al., 2014). A recent study in China found that about three-fourths of the smokers reported low cost as a major reason to buy cheaper cigarettes, particularly for smokers with a lower income level (Huang et al., 2014). Spending less per pack on cigarettes was also found to be associated with lower education, older age, and rural residence in our study. Other research reported that smokers with low socioeconomic status (SES) in Denmark were more likely to report the high cost of cigarettes as the motive for their intention to quit (Pisinger et al., 2011). It is likely that Chinese male smokers who buy the least expensive cigarettes, presumably of low SES with little resources otherwise, are more likely to make a quit attempt in an effort to reduce nonessential spending. Previous studies suggest that high cigarette price increases the likelihood of smoking cessation in countries with different income levels (Ross et al., 2011; Hyland et al., 2006; Kostova et al., 2014). These studies generally used aggregated cigarette prices following the price elasticity of demand approach to mitigate the endogeneity issue, or used indirect measures of cigarette price, such as smokers' choice to purchase discounted brands, or low-tax/untaxed cigarettes. Unlike countries such as the US, where taxes on cigarettes are regulated by Federal, state, and local government and prices could vary substantially across states, tobacco production and sales in China is monopolized by the China National Tobacco Corporation, and consequently, the cigarette price for the same brand is highly homogenous across the country. Our hypothesis may not extend to smokers at higher levels of SES as they could switch to cheaper cigarettes (Hyland et al., 2005, 2006). In addition, cessation behaviors could be country-specific, influenced by many environmental factors unaccounted for in this study such as social development and tobacco control policies. Research in some other countries indicates a lack of association between SES and quit attempts (Reid et al., 2010).

This study also documented variations in quit attempts according to whether a smoker was advised to quit by an HCP. A previous report suggested that Chinese smokers who visited a doctor or HCP between two surveys (about 12–18 months apart) were more likely to make a quit at tempt than were those who did not visit a doctor or HCP (Yang et al., 2011). Our results indicated that male daily smokers who visited an HCP but were not advised to quit did not differ significantly in whether they made a quit attempt from those who had not visited an HCP in the past 12 months. Thus, simply visiting a doctor or HCP was not an influencing factor for Chinese male daily smokers to make a quit attempt; what mattered most was to receive quit advice from their HCP during the visit. Smokers who visited an HCP and were advised to quit were almost three times as likely to make a quit attempt as those who did not visit an HCP at all, and were about twice as likely to make a quit attempt as those who visited an HCP but were not advised to quit.

Chinese smokers have traditionally underestimated the health risk caused by smoking (Persoskie et al., 2014), and the results of the current study demonstrate that having knowledge of tobacco harms is associated with quit attempts. Brief cessation advice by HCPs has been recommended as a cost-effective public health intervention to help smokers quit (Ministry of Health, People's Republic of China, 2012); hence, it is important for HCPs to provide patients who smoke with information on the harms of tobacco use and to give cessation advice.

The outcomes from mediation analyses supported the results of the logistic regression in showing that indirect effects were commonly mediated through knowledge of tobacco harms, exposure to smoking at home, and receiving advice to quit from an HCP. We found that smokers in rural areas were more likely to make a quit attempt because of the indirect infiuence of other variables. One plausible explanation is that HCPs might believe that patients from rural areas are in greater need of medical advice and be more likely to give it to them, as this effect is mediated by receiving advice to quit from an HCP. Mediation analysis also indicated that male smokers with a higher level of education tended to be advised to quit less by an HCP, an area potentially requiring intervention. Further understanding of these potential indirect paths could help tailor the delivery of interventions to increase quit attempts and cessation.

Our study has the following limitations. First, the data were crosssectional and, thus, the results cannot be interpreted as causal. Second, the current mediation analysis method does not allow inclusion of survey weights or consideration of complex sample structure for proper variance estimation. Therefore, the results from the mediation analysis are exploratory and require more research in order to be validated. Finally, we did not include exposure to secondhand smoke at work in our analysis, as this would have reduced our sample to those who were employed at the time of the survey, a limitation that would have greatly decreased sample size. In addition, previous studies have indicated a positive association between having smoking restrictions at home and making a quit attempt (Borland et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010, 2011b), but not between having a smoke-free policy at work and making a quit attempt (Hellman et al., 1991; Borland et al., 2010).

In conclusion, our results underscore the importance of raising awareness of the harms of tobacco use, of HCPs' delivering cessation advice, and of promoting-smoke-free homes to increase quit attempts among male smokers in China. Evidence-based tobacco control measures, as laid out in the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (World Health Organization, 2003), include conducting educational campaigns on awareness of the harms of tobacco use, establishing smoke-free policies, and integrating tobacco cessation advice into primary health care services; these measures have the potential to increase quit attempts and reduce smoking among male Chinese daily smokers.

Acknowledgments

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC) or the Global Adult Tobacco Survey partner organizations. Technical assistance is provided by the US CDC, the World Health Organization, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and RTI International. Program support is provided by the CDC Foundation.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Contributor-ship statement

LZ was the lead author and responsible for the overall contents of the manuscript. YS contributed to the initial concept of the study. LX assisted in literature review and refining the analysis. KP and SA provided key review for the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript.

Transparency document

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

References

- Borland R, Yong HH, Balmford J, et al. Motivational factors predict quit attempts but not maintenance of smoking cessation: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Project. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010;12:S4–S11. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention a. GTSS data http://www.cdc.gov/TOBACCO/Global/gtss/index.htm (Accessed Nov 14, 2013)

- Eriksen M, Mackay J, Ross H. The tobacco atlas. 4th ed. American Cancer Society; New York, NY; Atlanta, GA: 2012. World Lung Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Giovino GA, Mirza SA, Samet JM, et al. Tobacco use in 3 billion individuals from 16 countries: an analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional household surveys. Lancet. 2012;380:668–679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61085-X. (Erratum in Lancet 2012;380:1908 and Lancet 2013;382:128) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagimoto A, Nakamura M, Morita T, et al. Smoking cessation patterns and predictors of quitting smoking among the Japanese general population: a 1-year follow-up study. Addiction. 2009;105:164–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation and conditional process analysis. The Guilford Press; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hellman R, Cummings KM, Haughey BP, et al. Predictors of attempting and succeeding at smoking cessation. Health Educ. Res. 1991;6:77–86. doi: 10.1093/her/6.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia J, Yang GH, Li Q, et al. Methodology of the Global Adult Tobacco Survey in China, 2010. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2010;23:445–450. doi: 10.1016/S0895-3988(11)60005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Zheng R, Chaloupka F, et al. Chinese smokers’ cigarette purchase behaviours, cigarette prices and consumption: findings from the ITC China survey. Tob. Control. 2014;23:i67–i72. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Bauer J, Li Q, et al. Higher cigarette prices influence cigarette purchase patterns. Tob. Control. 2005;14(2):86–92. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Laux F, Higbee C, et al. Cigarette purchase patterns in four countries and the relationship with cessation: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob. Control. 2006;15(Suppl. 3):iii59–iii64. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostova D, Tesche J, Perucic A, et al. Exploring the relationship between cigarette prices and smoking among adults: a cross-country study of low- and middle-income nations. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014;16(Suppl. 1):S10–S15. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D, Rodriguez-Buno RL, Hu TW, et al. The potential effects of tobacco control in China: projections from the China SimSmoke simulation model. BMJ. 2014;348:g1134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Borland R, Yong HH, et al. Predictors of smoking cessation among adult smokers in Malaysia and Thailand: findings from the International Tobacco Control Southeast Asia Survey. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010;12:S34–S44. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Hsia J, Yang G. Prevalence of smoking in China in 2010. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011a;364:2469–2470. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1102459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Feng G, Jiang Y, et al. Prospective predictors of quitting behaviours among adult smokers in six cities in China: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) China Survey. Addiction. 2011b;106:1335–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03444.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:E442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, People’s Republic of China . Report on health hazards caused by smoking in China. People’s Health Press; Beijing, China: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Persoskie A, Mao Q, Chou WYS, et al. Absolute and comparative cancer risk perceptions among smokers in two cities in China. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014;16:899–903. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisinger C, Aadahl M, Toft U, et al. Motives to quit smoking and reasons to relapse differ by socioeconomic status. Prev. Med. 2011;52:48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid JL, Hammond D, Boudreau C, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in quit intentions, quit attempts, and smoking abstinence among smokers in four western countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010;12:S20–S33. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross H, Blecher E, Yan L, et al. Do cigarette prices motivate smokers to quit? New evidence from the ITC survey. Addiction. 2011;106(3):609–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutstein S. Wealth versus expenditure: comparison between the DHS wealth index and household expenditures in four departments of Guatemala. Calverton, Maryland; ORC Macro (unpublished): 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco market of China http://www.etmoc.com/market/Brandprice.asp (Accessed Nov 13, 2013)

- US Department of Health and Human Services . The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- White JS, Li J, Hu TW, et al. The effect of cigarette prices on brand-switching in China: a longitudinal analysis of data from the ITC China Survey. Tob. Control. 2014;23:i54–i60. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva, Switzerland: 2003. updated 2004, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Hammond D, Driezen P, et al. The use of cessation assistance among smokers from China: findings from the ITC China Survey. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Nonnemaker J, Sherrill B, et al. Attempts to quit smoking and relapse: factors associated with success or failure from the ATTEMPT cohort study. Addict. Behav. 2009;34:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]