Abstract

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in the brain have been implicated in the pathophysiological mechanisms in hypertension. The present study determined whether ER stress occurs in subfornical organ (SFO) and hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) in heart failure (HF), and how MAPK signaling interacts with ER stress and other inflammatory mediators. HF rats had significantly higher levels of the ER stress biomarkers (GRP78, ATF6, ATF4, XBP-1, P58IPK and CHOP) in SFO and PVN, which were attenuated by a 4-week intracerebroventricular (ICV) infusion of inhibitors selective for p44/42 MAPK (PD98059), p38 MAPK (SB203580) or JNK (SP600125). HF rats also had higher mRNA levels of tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, cyclooxygenase-2 and NF-κB p65 and lower mRNA level of IκB-α in SFO and PVN, compared with SHAM rats, and these indicators of increased inflammation were attenuated in the HF rats treated with the MAPK inhibitors. Plasma norepinephrine level was higher in HF than SHAM rats, but was reduced in the HF rats treated with PD98059 and SB203580. A 4-week ICV infusion of PD98059 also improved some hemodynamic and anatomic indicators of left ventricular function in HF rats. These data demonstrate that ER stress increases in the SFO and PVN of rats with ischemia-induced HF, and that inhibition of brain MAPK signaling reduces brain ER stress and inflammation and decreases sympathetic excitation in HF. An interaction between MAPK signaling and ER stress in cardiovascular regions of the brain may contribute to the development of HF.

Keywords: Brain, ER stress, mitogen-activated protein kinase, sympathetic activity, hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, subfornical organ, heart failure

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) is characterized by increased sympathetic nerve activity, driven in part by increases in brain inflammation and renin-angiotensin system (RAS) activity in cardiovascular regulatory regions of the brain, including the subfornical organ (SFO) and the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN). Activity of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascade that results in the phosphorylation of three major terminal effector kinases- p44/42 MAPK (also called extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases Erk1/2), p38 MAPK and c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) – also increases in the SFO and PVN in HF.1 Angiotensin II (ANG II) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (PICs) both activate MAPK signaling, which has been implicated in upregulation of AT1-R expression in the SFO and PVN and sympathetic excitation in HF.2, 3 However, the mechanisms by which MAPK activates sympathetic nerve activity remain poorly defined.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an intracellular organelle that plays an important role in the synthesis, folding and translocation of proteins. ER stress is caused by an excessive accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER lumen,4 which evokes the unfolded protein response (UPR) with activation of a series of downstream signal transduction pathways including MAPK signaling.4, 5 In peripheral tissues, ANG II and PICs can also induce ER stress and the UPR.6, 7 ER stress has been implicated in the pathophysiology of a variety of chronic disease states including diabetes mellitus,8 obesity9–11 and cardiovascular diseases.12 More recently, ER stress in the brain has been found to be involved in the regulation of sympathetic drive and cardiovascular function in ANG II-induced hypertension13 and in obesity.14

Since RAS activity and inflammation are both upregulated in the brain of HF rats,15–19 and both can induce ER stress and MAPK signaling in peripheral tissues, we investigated whether indicators of ER stress are upregulated in SFO and PVN in HF rats, and whether MAPK signaling has a role in that process. We also examined the effects of inhibiting brain MAPK signaling on gene expression of the nuclear transcription factor kappa B (NF-κB) and the inflammatory mediators tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and COX-2, circulating norepinephrine (NE) as an indicator of sympathetic nerve activity. Because brain p44/42 MAPK is known to contribute to sympathetic activation in heart failure3 and hypertension,20 and the p44/42 MAPK inhibitor proved particularly effective in reducing indicators of ER stress in the present study, we further examined its effects on anatomical and physiological indicators of heart failure.

METHODS

Animals

Experiments were carried out using adult male Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 275–325g, which were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Indianapolis). The rats were housed in temperature controlled (23 ± 2°C) and light-controlled rooms in University of Iowa Animal Care Facility and fed rat chow ad libitum. All experimental procedures were approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Experimental protocols

Rats underwent coronary artery ligation to induce heart failure (HF) or a sham operation (SHAM).21 All rats underwent echocardiography within 24 hours of surgery to determine left ventricular function. Only animals with large infarctions (ischemic zone >35 % of the circumference of the left ventricle) were assigned to HF treatment groups.

HF rats underwent a 4-week ICV infusion (0.25 μl/hr, 0.6 mmol/L) of the p44/42 MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (HF+PD), the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (HF+SB), the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (HF+SP), or vehicle (VEH; HF+VEH) via osmotic micro-pumps (Alzet, Cupertino, CA), beginning within 24 hours of coronary ligation or sham surgery. SHAM rats receiving ICV VEH (SHAM+VEH) served as control. Four weeks after induction of HF, some rats underwent a second echocardiogram to assess the effects of the treatment protocols on left ventricular (LV) function.

At the conclusion of the treatment protocols, some animals were anesthetized with urethane and a Millar catheter (Millar, Houston, TX) was inserted in the right carotid artery and advanced into the LV to measure LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) and the maximal rate of rise of LV systolic pressure (LV dP/dt max). These animals were then euthanized to collect heart and lungs for anatomical studies. Others were decapitated or transcardially perfused while deeply anesthetized to collect brain tissues for molecular and immunofluorescent studies.

Real-time PCR and ELISA studies

Real-time PCR was performed on SFO, PVN and cortical tissues from all 5 groups (n=6 in each group) to measure gene expression of the ER stress biomarkers glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), activating transcription factor (ATF)-6, RNA-activated protein kinase p58IPK and C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, COX-1 and COX-2, and the NF-κB components p65 and IκB-α.

Trunk blood from rats in all 5 groups (n=6 in each group) was assayed by ELISA for plasma concentration of NE, a general indicator of the level of sympathetic activation.

Western blot and immunofluorescent studies

Further studies were conducted to determine the effect of inhibiting p44/42 MAPK signaling on ER stress-related proteins in SFO and PVN. Western blot was used to measure the protein levels of GRP78, X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) and ATF4 in the SHAM+VEH, HF+VEH and HF+PD rats (n=6 in each group). Immunofluorescent staining was used to examine the expression of GRP78, XBP-1 and ATF4 in the HF+VEH and HF+PD rats (n=6 in each group).

Hemodynamic and anatomical assessment

The presence of myocardial scar was confirmed visually in all HF groups. In the SHAM+VEH, HF+VEH and HF+PD groups, the heart weight to body weight (BW), right ventricular (RV) weight to BW and wet lung weight to BW ratios were determined.

Specific Materials and Methods

Further description of materials and methods is available in the online data supplement (http://hyper.ahajournals.org).

Statistical Analysis

The significance of differences among groups was analyzed by 2-way repeated-measure ANOVA followed by post hoc Fisher’s test. For other unpaired data, a Student’s t-test was used for comparison between groups. p< 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Echocardiographic assessment of heart failure

Echocardiographic assessments within 24 hours after coronary artery ligation demonstrated that LVEF was reduced and LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) was increased in rats with HF, compared with SHAM (Table S1). The HF animals assigned to each treatment group 24 hours after coronary artery ligation were well-matched with regard to % ischemic zone and LV ejection fraction (LVEF). Repeat echocardiograms obtained in some HF+VEH rats at 4 weeks revealed that LVEF did not change significantly but LV volume/mass ratio increased as heart failure progressed (Table S1).

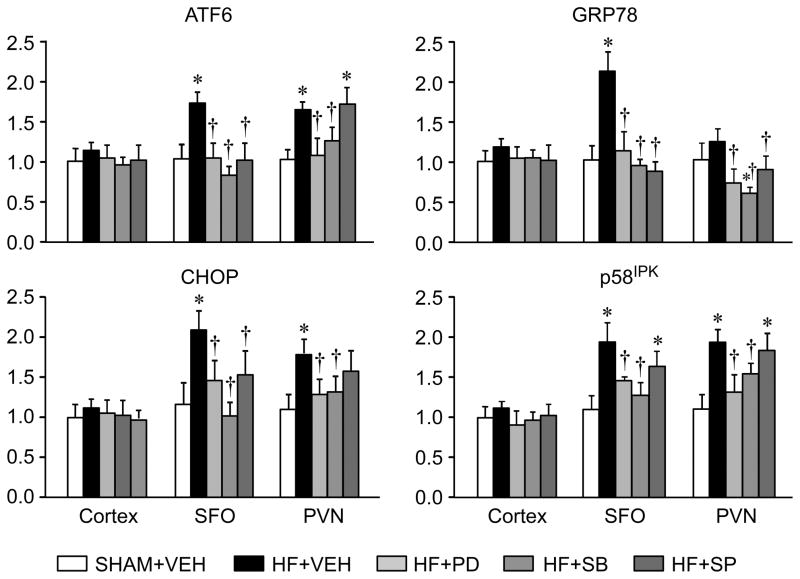

Effects of MAPK inhibitors on gene expression of ER stress markers

HF+VEH rats had significantly higher mRNA levels for the ER stress biomarkers GRP78, ATF6, p58IPK and CHOP in SFO and PVN 4 weeks after coronary ligation, compared with SHAM+VEH rats (Figure 1). HF+PD and HF+SB rats had significantly lower mRNA levels of these ER stress biomarkers in both nuclei, with SB203580 being most effective in SFO and PD98059 most effective in PVN. HF+SP rats had lower mRNA levels of GRP 78, ATF6, and CHOP, but not p58IPK, in SFO and PVN. There were no differences across treatment groups in the gene expression of these ER stress biomarkers in cerebral cortex.

Figure 1.

Quantitative analysis by real-time PCR showing the mRNA expression of ER stress biomarkers GRP78, ATF6, P58IPK and CHOP in subfornical organ (SFO), hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and cerebral cortex in heart failure (HF) rats treated ICV for 4 weeks with the p44/42 MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (HF+PD), the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 HF+SB), the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (HF+SP) or vehicle (VEH, HF+VEH) and VEH-treated SHAM (SHAM+VEH) rats. Values are mean ± SEM (n=6 for each group) and expressed as a fold change relative to SHAM+VEH control. * p<0.05, vs SHAM+VEH; † p< 0.05, HF+PD, HF+SB, and HF+SP vs HF+VEH.

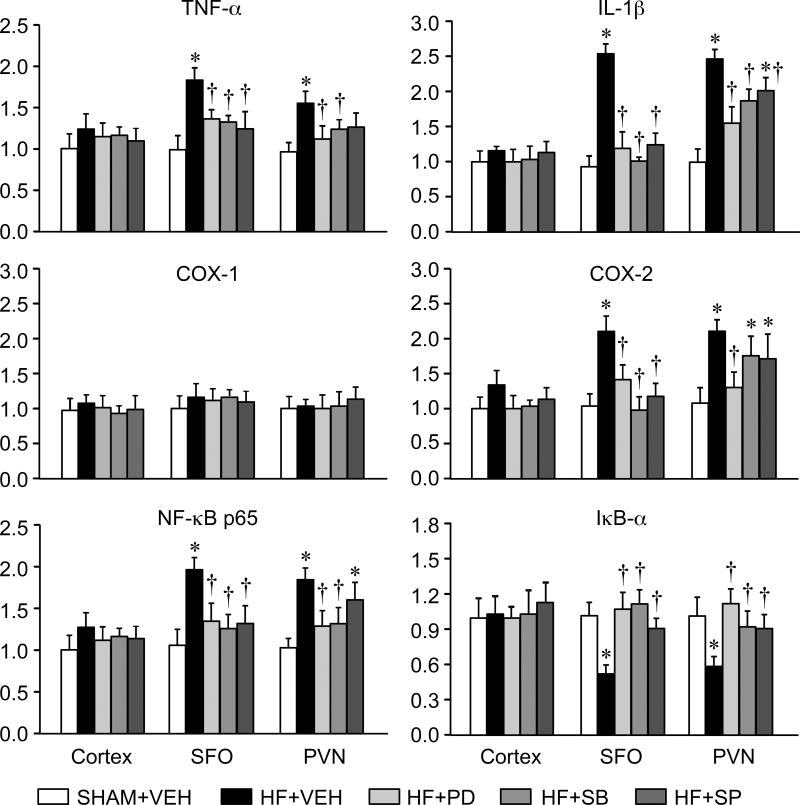

Effects of MAPK inhibitors on gene expression of inflammatory mediators

The HF+VEH rats had higher mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and COX-2 in SFO and PVN, compared with the SHAM-VEH rats (Figure 2). HF+PD, HF+SB and HF+SP rats all had lower mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and COX-2 in SFO and PVN than HF+VEH rats. There was no difference in COX-1 mRNA across groups. HF+VEH rats also had higher NF-κB p65 mRNA levels and lower IκB-α mRNA levels in SFO and PVN, compared with SHAM+VEH rats. These two components of NF-κB were normalized in the HF+PD and HF+SB rats. There were no differences across treatment groups in the gene expression of these inflammatory mediators in cerebral cortex.

Figure 2.

Quantitative analysis by real-time PCR showing the mRNA expression of the inflammatory mediators TNF-α, IL-1β, COX-1, COX-2, NF-kB p65 and IkB-α in subfornical organ (SFO), hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and cerebral cortex in heart failure (HF) rats treated ICV for 4 weeks with the p44/42 MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (HF+PD), the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (HF+SB), the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (HF+SP) or VEH (HF+VEH) and VEH-treated SHAM rats (SHAM+VEH). Values are mean ± SEM (n=6 for each group) and expressed as a fold change relative to SHAM+VEH control. * p<0.05, vs SHAM+VEH; † p< 0.05, HF+PD, HF+SB, and HF+SP vs HF+VEH.

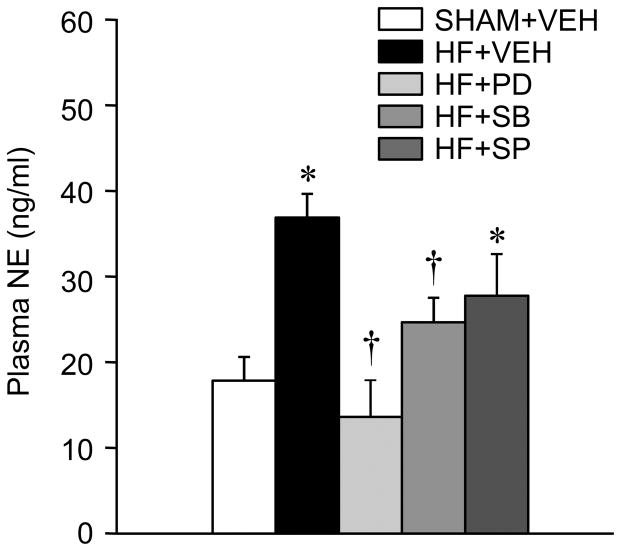

Effects of MAPK inhibitors on plasma NE

Plasma NE levels were higher in HF+VEH compared with SHAM+VEH rats (Figure 3). In HF+PD and HF+SB rats, the plasma concentrations of NE were significantly lower than those in the HF+VEH rats. The reduction in plasma NE levels in HF+SP rats did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 3.

Plasma NE level in VEH-treated SHAM (SHAM+VEH) rats and heart failure (HF) rats treated ICV for 4 weeks with the p44/42 MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (HF+PD), the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (HF+SB), the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (HF+SP) or VEH. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. * p<0.05, vs SHAM+VEH; † p<0.05, HF+PD, HF+SB, and HF+SP vs HF+VEH.

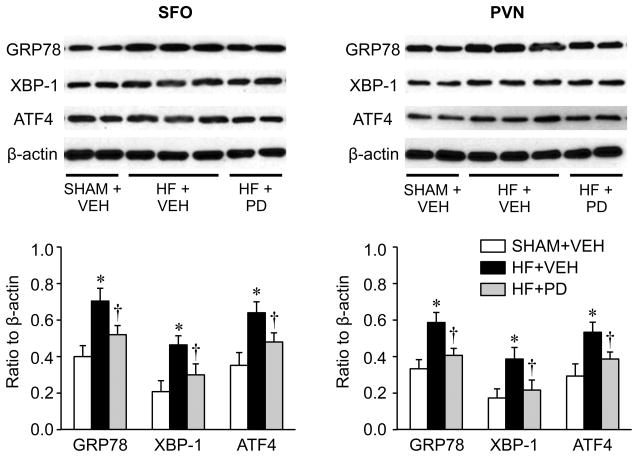

Effects of the p44/42 MAPK inhibitor on ER stress proteins

To validate the significance of real-time PCR data, Western blot was used to measure the protein levels of several ER stress biomarkers, GRP78, XBP-1 and ATF4, in the SFO and PVN in the SHAM+VEH, HF+VEH and HF+PD rats (Figure 4). These data confirmed the increased expression of ER stress in the SFO and PVN of the HF+VEH rats, compared with the SHAM+VEH rats, and a lower level of ER stress biomarkers in HF+PD rats.

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis showing the expression of ER stress biomarkers GRP78, XBP-1 and ATF4 in subfornical organ (SFO) and hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) in VEH-treated SHAM (SHAM+VEH) rats and heart failure (HF) rats treated for 4 weeks with ICV p44/42 MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (HF+PD) or VEH (HF+VEH). Values are expressed as means ± SEM and normalized to β-actin (n=6 in each group). * p<0.05, vs SHAM+VEH; † p< 0.05, HF+PD vs HF+VEH. Representative Western bands are shown above the bar group.

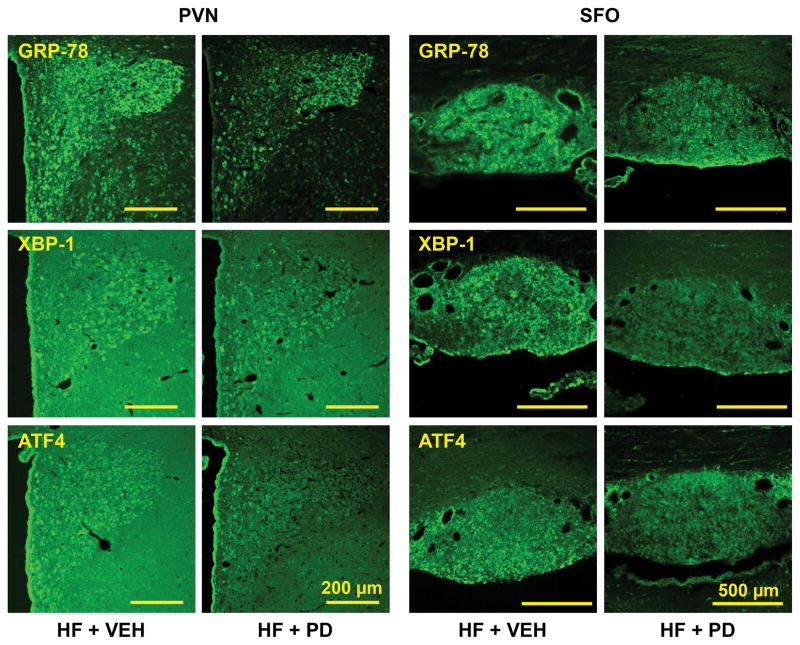

Confocal immunofluorescent images revealed intense expression of GRP78 immunoreactivity in the SFO and PVN (Figure 5) in HF rats. The ER stress biomarkers XBP-1 and ATF4 were also expressed in the SFO and PVN, but to a lesser extent. In the PVN, these ER stress biomarkers were expressed in dorsal parvocellular, medial parvocellular, ventrolateral parvocellular and magnocellular regions, the four commonly recognized subdivisions. In the SFO, they were evenly expressed throughout the nucleus. In HF+PD rats, the expression of GRP78, XBP-1 and ATF4 in SFO and PVN was reduced.

Figure 5.

Laser confocal images showing the immunofluorescent staining of ER stress biomarkers GRP78, XBP-1 and ATF4 in subfornical organ (SFO) and hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) in VEH-treated heart failure (HF+VEH) rats and HF rats treated ICV for 4 weeks with the p44/42 MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (HF+PD).

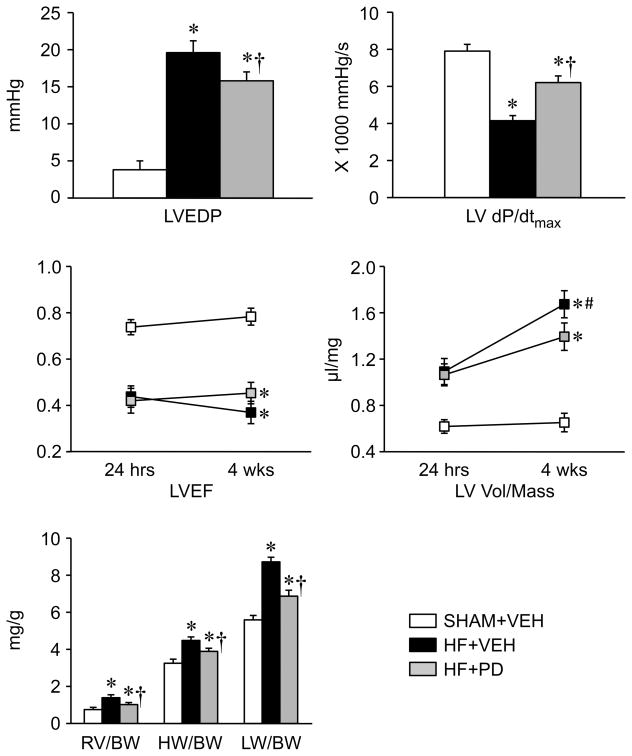

Effects of the p44/42 MAPK inhibitor on indicators of HF

Echocardiography revealed no significant improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) or LV volume/mass ratio in HF rats treated with PD, compared with HF rats treated with VEH (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Echocardiographic, hemodynamic and anatomical measurements in VEH-treated SHAM (SHAM+VEH) rats and heart failure (HF) rats treated ICV for 4 weeks with the p44/42 MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (HF+PD) or VEH (HF+VEH). Values are expressed as means ± SEM. * p<0.05, vs SHAM+VEH; † p<0.05, HF+PD vs HF+VEH, # p<0.05, 24 hrs vs 4 wks. LVEF: left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction; BW: body weight; RV: right ventricular weight; HW: heart weight; LW: Lung weight; LVEDP: LV end-diastolic pressure; LV dP/dt max: maximum rate of rise of LV pressure; LV vol/mass: the ratio of LV volume to LV myocardial mass.

Hemodynamic assessment at the completion of the experiments revealed that HF+VEH rats had a higher LV end diastolic pressure (LVEDP), and a lower LV peak systolic pressure (LVPSP) and maximal rate of rise of LV systolic pressure (LV dP/dt max), than SHAM+VEH rats. HF+PD rats had increased LV dP/dt max, decreased LVEDP compared with HF+VEH rats, but these values were still significantly different from those in SHAM+VEH rats (Figure 6). LVPSP was not significantly different in HF+PD versus HF+VEH rats (Table S1).

The anatomic assessment exhibited that the heart /BW, RV/BW and lung /BW ratios were substantially higher in HF+VEH compared with SHAM+VEH rats, but were significantly reduced in the HF+PD rats (Figure 6).

DISCUSSION

We previously reported that the expression of phosphorylated p44/42 MAPK, p38 MAPK and JNK is upregulated in the SFO and PVN in HF,2, 3 and that increased activity of MAPK signaling in the brain plays an important role in the neurohumoral activation in HF rats.3 In part, this appears to be related to MAPK-mediated upregulation of brain RAS activity.2, 22 The present study sought to determine whether brain MAPK signaling in HF stimulates the activity of other central mechanisms that may contribute to sympathetic excitation. We observed increases in biomarkers of ER stress and inflammation in the SFO and PVN of HF rats that were significantly attenuated in HF rats treated with a continuous ICV infusion of selective inhibitors for each of the major MAPK signaling pathways. Among these, inhibitors of the p44/42 and p38 MAPK signaling pathways were most effective. Peripheral indicators confirmed an associated reduction in plasma NE, a general indicator of sympathetic activity, and improvements in cardiac remodeling and cardiac function. These new findings, taken together with our previous results,2, 3, 23 suggest that brain MAPK signaling contributes significantly to the excitatory neurochemical milieu driving sympathetic activity in HF.

Emerging evidence suggests a role for brain ER stress in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases. Young et al.13, 24 reported that ER stress in the SFO plays an important role in mediating the progression of ANG II-induced hypertension in mice. Chan et al. 25 reported that ER stress is upregulated in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of spontaneously hypertensive rats and contributes to the development of hypertension. However, the presence of ER stress is not uniformly associated with sympathetic activation. One study in DOCA-salt mice reported that ER stress does not contribute to the blood pressure response even though it does mediate the DOCA-induced saline intake.26 Another reported an increase in mRNA for biomarkers of ER stress but no increase in ER stress proteins in SFO and PVN of DOCA-salt mice, and no effect of ICV treatment with the ER stress inhibitor tauroursodeoxycholic acid on the development of hypertension.27 Thus, the contribution of ER stress to sympathetic excitation may vary depending upon the experimental model studied.

The excitatory milieu of the HF brain might be considered highly conducive to the induction of ER stress. Increased RAS activity, inflammation, and reactive oxygen species – all present in cardiovascular regulatory regions of the brain in that setting17–19, 28- are all reported to induce ER stress.7, 13, 29–32 The present study confirms that ER stress is present in the SFO and PVN of rats with ischemia-induced HF, but its contribution to the augmented sympathetic activity in this model remains to be determined.

The present study also highlights an underappreciated relationship between MAPK signaling and ER stress. While MAPK signaling is known to occur downstream from ER stress,4, 5 many of the factors that drive ER stress are products of MAPK signaling. Phosphorylated MAPKs act upon the transcription factors activator protein-1 and NF-κB,33, 34 which can upregulate the expression of angiotensinogen, the precursor of ANG II, and the ANG II type 1 receptor, as well as the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β and COX-2. 35–38 Thus, inhibition of MAPK signaling in HF may interrupt a feed-forward mechanism driving ER stress and its downstream consequences. The observation that the MAPK inhibitors reduce the expression of the inflammatory mediators TNF-α, IL-1β and COX-2 and markers of ER stress in the PVN and SFO in HF rats is consistent with that hypothesis. Inhibition of MAPK signaling also normalized the NF-κB activity in the SFO and PVN, suggesting that MAPK-driven NF-κB activity contributes to the production of cytokines in the HF brain.

Chronic ICV treatment of HF rats with either the p44/42 MAPK or the p38 MAPK inhibitor significantly reduced circulating NE levels, a general indicator of the level of sympathetic nerve activity. Because central inhibition of p44/42 MAPK signaling is known to have beneficial effects in heart failure3 and angiotensin II-induced hypertension,20 we examined the effects of central inhibition of MAPK activity on cardiac function. Consistent with previous studies of the effects of central interventions that reduce sympathetic drive,39–41 there was no improvement in echocardiographically defined LVEF or LV volume/mass ratio. However, LVEDP, wet lung/BW and RV/BW ratios were reduced and LV max dP/dt was improved, likely reflecting reduced sympathetic drive to the kidneys and the vasculature with accompanying reductions in preload and afterload. Similar improvements of LV function were observed in prior studies in which targeted interventions in brain renin-angiotensin system activity reduced sympathetic activity in HF rats.40–43

Perspectives

The present study extends understanding of the role of brain MAPK signaling in HF. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence that MAPK signaling drives ER stress and the UPR in cardiovascular regulatory regions of the brain in HF, likely by affecting transcriptional upregulation of renin-angiotensin system activity and the production of proinflammatory cytokines. Interrupting this apparent feed-forward central circuit by targeting brain MAPK signaling – and particularly p44/42 or p38 MAPK signaling - may simultaneously treat multiple central mechanisms that contribute to the augmented sympathetic nerve activity in HF.

How to achieve inhibition of brain MAPK signaling remains problematic. Microparticle approaches providing sustained circulating drug levels and nanoparticle approaches to facilitating passage across the blood-brain barrier offer promise. In addition, advantage might be taken of the vascular vulnerability of circumventricular organs like the SFO, whose activity influences intraparenchymal nuclei regulating sympathetic drive. Because of the many similarities in the central neurochemical abnormalities and neural mechanisms in HF and hypertension, the findings of this study may also provide important new insights into potential therapeutic interventions in hypertension.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is New?

Expression of ER stress biomarkers including GRP78, ATF6, P58IPK, CHOP, XBP-1 and ATF4 is upregulated in SFO and PVN, two key cardiovascular autonomic regions of the brain, in rats with heart failure.

Chronic central inhibition of MAPK signaling reduces markers of ER stress and inflammation in PVN and SFO of rats with heart failure.

Chronic central inhibition of MAPK signaling decreases sympathetic nerve activity and reduces the peripheral manifestations of heart failure.

What Is Relevant?

In addition to its known effects to upregulate the brain renin-angiotensin system, MAPK signaling augments the expression of ER stress and inflammatory mediators in cardiovascular regions of the brain in heart failure.

Similar mechanisms may contribute to neurogenic hypertension.

Summary

MAPK signaling contributes to ER stress and inflammation in cardiovascular regions of the brain in heart failure. Inhibition of brain MAPK signaling reduces sympathetic activation and the progression of cardiac dysfunction in heart failure. Brain MAPK signaling is a potential novel therapeutic target in heart failure.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Kathy Zimmerman, RDMS/RDCS/FASE, for diligent and expert assistance in the performance of the echocardiograms.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This material is based upon work supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development (to RBF) and the University of Iowa (to RBF), and by RO1HL096671(to RBF), R01HL073986 (to RBF) and S10 OD019941 (to RMW) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None

References

- 1.Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers Gibson T, Xu BE, Karandikar M, Berman K, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: Regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:153–183. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei SG, Yu Y, Zhang ZH, Weiss RM, Felder RB. Mitogen-activated protein kinases mediate upregulation of hypothalamic angiotensin II type 1 receptors in heart failure rats. Hypertension. 2008;52:679–686. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.113639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei SG, Yu Y, Zhang ZH, Weiss RM, Felder RB. Angiotensin II-triggered p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates sympathetic excitation in heart failure rats. Hypertension. 2008;52:342–350. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.110445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darling NJ, Cook SJ. The role of MAPK signalling pathways in the response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843:2150–2163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xue X, Piao JH, Nakajima A, Sakon-Komazawa S, Kojima Y, Mori K, Yagita H, Okumura K, Harding H, Nakano H. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) induces the unfolded protein response (UPR) in a reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent fashion, and the UPR counteracts ROS accumulation by TNF-alpha. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33917–33925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505818200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J, Wang G, Wang Y, Liu Q, Xu W, Tan Y, Cai L. Diabetes- and angiotensin II-induced cardiac endoplasmic reticulum stress and cell death: Metallothionein protection. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:1499–1512. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eizirik DL, Cardozo AK, Cnop M. The role for endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetes mellitus. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:42–61. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hummasti S, Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation in obesity and diabetes. Circ Res. 2010;107:579–591. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.225698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozcan U, Cao Q, Yilmaz E, Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Ozdelen E, Tuncman G, Gorgun C, Glimcher LH, Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes. Science. 2004;306:457–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1103160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tripathi YB, Pandey V. Obesity and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stresses. Front Immunol. 2012;3:240. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minamino T, Kitakaze M. ER stress in cardiovascular disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:1105–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young CN, Cao X, Guruju MR, Pierce JP, Morgan DA, Wang G, Iadecola C, Mark AL, Davisson RL. ER stress in the brain subfornical organ mediates angiotensin-dependent hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3960–3964. doi: 10.1172/JCI64583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cakir I, Cyr NE, Perello M, Litvinov BP, Romero A, Stuart RC, Nillni EA. Obesity induces hypothalamic endoplasmic reticulum stress and impairs proopiomelanocortin (POMC) post-translational processing. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:17675–17688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.475343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu Y, Zhang ZH, Wei SG, Chu Y, Weiss RM, Heistad DD, Felder RB. Central gene transfer of interleukin-10 reduces hypothalamic inflammation and evidence of heart failure in rats after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2007;101:304–312. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.148940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei SG, Zhang ZH, Yu Y, Weiss RM, Felder RB. Central actions of the chemokine stromal cell-derived factor 1 contribute to neurohumoral excitation in heart failure rats. Hypertension. 2012;59:991–998. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.188086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Francis J, Zhang ZH, Weiss RM, Felder RB. Neural regulation of the proinflammatory cytokine response to acute myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H791–797. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00099.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan J, Wang H, Leenen FH. Increases in brain and cardiac AT1 receptor and ACE densities after myocardial infarct in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H1665–1671. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00858.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zucker IH, Xiao L, Haack KK. The central renin-angiotensin system and sympathetic nerve activity in chronic heart failure. Clin Sci. 2014;126:695–706. doi: 10.1042/CS20130294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu Y, Xue BJ, Zhang ZH, Wei SG, Beltz TG, Guo F, Johnson AK, Felder RB. Early interference with p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus attenuates angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;61:842–849. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Francis J, Weiss RM, Wei SG, Johnson AK, Felder RB. Progression of heart failure after myocardial infarction in the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R1734–1745. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.5.R1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei SG, Yu Y, Zhang ZH, Felder RB. Angiotensin II upregulates hypothalamic AT1 receptor expression in rats via the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1425–1433. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00942.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei SG, Zhang ZH, Yu Y, Felder RB. Central SDF-1/CXCL12 expression and its cardiovascular and sympathetic effects: The role of angiotensin II, TNF-alpha, and MAP kinase signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:H1643–1654. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00432.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young CN, Li A, Dong FN, Horwath JA, Clark CG, Davisson RL. Endoplasmic reticulum and oxidant stress mediate nuclear factor-kappa B activation in the subfornical organ during angiotensin II hypertension. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2015;308:C803–812. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00223.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chao YM, Lai MD, Chan JY. Redox-sensitive endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy at rostral ventrolateral medulla contribute to hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2013;61:1270–1280. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jo F, Jo H, Hilzendeger AM, Thompson AP, Cassell MD, Rutkowski DT, Davisson RL, Grobe JL, Sigmund CD. Brain endoplasmic reticulum stress mechanistically distinguishes the saline-intake and hypertensive response to deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt. Hypertension. 2015;65:1341–1348. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia H, de Queiroz TM, Sriramula S, Feng Y, Johnson T, Mungrue IN, Lazartigues E. Brain ACE2 overexpression reduces DOCA-salt hypertension independently of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;308:R370–378. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00366.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang YM, Ma Y, Elks C, Zheng JP, Yang ZM, Francis J. Cross-talk between cytokines and renin-angiotensin in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus in heart failure: Role of nuclear factor-kappa B. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:671–678. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okada K, Minamino T, Tsukamoto Y, Liao Y, Tsukamoto O, Takashima S, Hirata A, Fujita M, Nagamachi Y, Nakatani T, Yutani C, Ozawa K, Ogawa S, Tomoike H, Hori M, Kitakaze M. Prolonged endoplasmic reticulum stress in hypertrophic and failing heart after aortic constriction: Possible contribution of endoplasmic reticulum stress to cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Circulation. 2004;110:705–712. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000137836.95625.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu H, Zhao S, Zhang Y, Wu J, Peng H, Fan J, Liao J. Reactive oxygen species-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction contribute to polydatin-induced apoptosis in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cne cells. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:3695–3703. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denis RG, Arruda AP, Romanatto T, Milanski M, Coope A, Solon C, Razolli DS, Velloso LA. TNF-alpha transiently induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and an incomplete unfolded protein response in the hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 2010;170:1035–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santos CX, Nabeebaccus AA, Shah AM, Camargo LL, Filho SV, Lopes LR. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and NOX-mediated reactive oxygen species signaling in the peripheral vasculature: Potential role in hypertension. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:121–134. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turjanski AG, Vaque JP, Gutkind JS. MAP kinases and the control of nuclear events. Oncogene. 2007;26:3240–3253. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang F, Steelman LS, Lee JT, Shelton JG, Navolanic PM, Blalock WL, Franklin RA, McCubrey JA. Signal transduction mediated by the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway from cytokine receptors to transcription factors: Potential targeting for therapeutic intervention. Leukemia. 2003;17:1263–1293. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsatsanis C, Androulidaki A, Venihaki M, Margioris AN. Signalling networks regulating cyclooxygenase-2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:1654–1661. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siebenlist U, Franzoso G, Brown K. Structure, regulation and function of NF-kappa B. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1994;10:405–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.10.110194.002201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cowling RT, Gurantz D, Peng J, Dillmann WH, Greenberg BH. Transcription factor NF-kappa B is necessary for up-regulation of type 1 angiotensin II receptor mRNA in rat cardiac fibroblasts treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha or interleukin-1 beta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5719–5724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brasier AR, Jamaluddin M, Han Y, Patterson C, Runge MS. Angiotensin II induces gene transcription through cell-type-dependent effects on the nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB) transcription factor. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;212:155–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kang YM, Zhang ZH, Xue B, Weiss RM, Felder RB. Inhibition of brain proinflammatory cytokine synthesis reduces hypothalamic excitation in rats with ischemia-induced heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H227–236. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01157.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Francis J, Weiss RM, Wei SG, Johnson AK, Beltz TG, Zimmerman K, Felder RB. Central mineralocorticoid receptor blockade improves volume regulation and reduces sympathetic drive in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H2241–2251. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.5.H2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Francis J, Wei SG, Weiss RM, Felder RB. Brain angiotensin-converting enzyme activity and autonomic regulation in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H2138–2146. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00112.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang BS, Leenen FH. Blockade of brain mineralocorticoid receptors or Na+ channels prevents sympathetic hyperactivity and improves cardiac function in rats post-MI. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2491–2497. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00840.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lal A, Veinot JP, Ganten D, Leenen FH. Prevention of cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction in transgenic rats deficient in brain angiotensinogen. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.