Abstract

Background

Rare variants (<1%) likely contribute significantly to risk for common diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in specific patient subsets, such as those with high familiality. They are, however, extraordinarily challenging to identify.

Methods

To discover candidate rare variants associated with IBD, we performed whole exome sequencing (WES) on six members of a pediatric-onset IBD family with multiple affected individuals. To determine whether the variants discovered in this family are also associated with non-familial IBD, we investigated their influence on disease in two large case-control (CC) series.

Results

We identified two rare variants, rs142430606 and rs200958270, both in the established IBD-susceptibility gene IL17REL, carried by all four affected family members and their obligate-carrier parents. We then demonstrated that both variants are associated with sporadic ulcerative colitis (UC) in two independent datasets. For UC in CC 1: rs142430606 (OR=2.99, Padj=0.028; MAFcases=0.0063, MAFcontrols=0.0021); rs200958270 (OR=2.61, Padj=0.082; MAFcases=0.0045, MAFcontrols=0.0017). For UC in CC 2: rs142430606 (OR=1.94, P=0.0056; MAFcases=0.0071, MAFcontrols=0.0045); rs200958270 (OR=2.08, P=0.0028; MAFcases=0.0071, MAFcontrols=0.0042).

Conclusions

We discover in a family and replicate in two CC datasets two rare susceptibility variants for IBD, both in IL17REL. Our results illustrate that WES performed on disease-enriched families to guide association testing can be an efficient strategy for the discovery of rare disease-associated variants. We speculate that rare variants identified in families and confirmed in the general population may be important modifiers of disease risk for patients with a family history, and that genetic testing of these variants may be warranted in this patient subset.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, familial inflammatory bowel disease, inflammatory bowel disease risk, complex disease genetics, whole exome sequencing

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are chronic inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tract, of which the major forms are Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC) and IBD-unclassified (IBD-U). To date, 163 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and multiple HLA alleles associated with IBD have been discovered (reviewed in (1–4)). Despite this success, all variants identified thus far explain only a relatively small proportion of the overall genetic contribution to IBD risk (13.6% for CD and 7.5% for UC) (4).

Rare variants are likely to be important factors for disease susceptibility in specific patient subsets, such as familial clusters of affected individuals. Despite their expected significance, the identification of rare disease-associated variants that do not segregate in strict Mendelian fashion has been notoriously difficult, because association studies are largely underpowered for their detection, especially after correcting for multiple testing when performing genome-wide studies of association. Although technological advances such as next-generation sequencing have allowed for the rapid cataloguing of rare variants in large numbers of individuals, effective methodological approaches to investigate their association with complex traits remain less well-developed. Traditional methods for the discovery of causative variants in familial aggregates of complex diseases, such as linkage mapping, require large numbers of affected and unaffected individuals from multiple families, and yield regions in which the true causative variant must lie; the identification of the true causal mutation often requires considerable further sequencing and analysis. Other strategies, such as whole exome sequencing (WES) of large numbers of probands from multi-case families, have led to the discovery of genes enriched for rare variants, but the actual contribution of each individual variant to disease risk is not commonly assessed (5–7). Here, in a study of familial IBD, we chose an alternative approach that fully leverages the reduced genetic complexity of familial disease for the discovery of rare high-penetrance variants. We sequenced only a single family with pediatric-onset IBD and identified two rare candidate causative variants, both of which were associated with IBD in two large case-control sets. Our success suggests that this can be is a powerful and efficient strategy to discover rare high-penetrance variants underlying complex human diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects

The family analyzed was ascertained through the Pediatric IBD Program at The University of Chicago (BSK). All study subjects provided written informed consent to participate in a study of IBD genetics that was approved by the local institutional review board. To protect the anonymity of the study subjects, the family pedigree was altered in ways that do not affect the genetic analysis.

Exome capture and sequencing

Germline DNA (1ug) isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes was used as a template for WES for each of six family members. Exome capture was performed with SureSelect Human All Exon V4+UTRs kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). 100 bp paired-end sequence reads were generated using an Illumina HiSeq2000 (Illumina, San Diego, USA). An average of 5.31 Gigabytes of data was generated for each sample.

Variant calling and Quality Control (QC)

The sequence reads were aligned to the human reference genome hg19 using three different alignment algorithms: Bowtie 2 (8); BWA (9); and Novoalign (10). Exon coverage was calculated at 1x, 5x, 10x and 20x using BEDTools (11). Read duplicates were removed using Picardtools MarkDuplicates program (12). The alignment was post-processed by GATK 1.6 for InDel realignment and base quality score recalibration. For each alignment, four different genotype calling algorithms (Atlas2 (13); FreeBayes (14); GATK UnifiedGenotyper (15, 16); and SAMtools (17)) were used for variant detection and genotype calling (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which illustrates our analysis pipeline). Variants with low quality (QUAL <50.0), low coverage (depth <6), and strand bias were filtered from further consideration. To maximize calling accuracy, only variants identified by at least two alignment algorithms and called by at least two genotype calling algorithms were carried forward for analysis. Minor allele frequencies were estimated using all samples in The 1000 Genomes Project database (18) (phase 1, release v3, 20101123; URL: http://browser.1000genomes.org) and the NHLBI GO Exome sequencing project (ESP) database (ESP6500SI-V2-SSA137; URL: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/; 06/2012 accessed). Variants were annotated using ANNOVAR (19). An average of 16,045 high-confidence variants were identified for each individual.

Identification of candidate IBD variants

To investigate rare variation, we required that variants passing the QC pipeline above: 1) have a minor allele frequency <0.01; 2) be either non-synonymous, a splice site modifier, or create a stop codon; 3) be deleterious as predicted by either SIFT (20) or Polyphen-2 (21); and 4) be shared among all affected children and their obligate carrier parents. Variants were further categorized as likely to influence IBD risk in this family if they were found in genes previously associated with IBD (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which lists known IBD-associated genes), based upon a review of the literature and the catalog of genes associated with IBD, CD, or UC (4, 22).

Sanger sequencing confirmation of IL17REL rare variants

To confirm the genotypes of rs142430606 and rs200958270 in the germline of all six family members, we performed Sanger sequencing. The genomic region containing rs142430606 was amplified using primers synthesized by IDT (Coralville, IA) (forward primer 5’- CACACCCATACCCATGACAC-3’; reverse primer 5’ CCCAACTGGTAGAGAACTGC-3’). The region containing rs200958270 was amplified using: forward primer 5’- CTAAGCTCCAGCCATGCAAGTG-3’; reverse primer 5’-CCTCATGGTGGAGTCAGACTGG-3’). PCR was performed as 50 µL reactions containing Phusion GC Buffer, 200nM dNTP, 3% DMSO, Phusion polymerase (LifeTechnologies, Grand Island, NY), 0.5 µM forward and 0.5 µM reverse primers, and 50 ng DNA. Reactions were carried out in a 48-well plate using a BioRad C1000 Touch Thermo Cycler (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The PCR cycling protocol was: 1 cycle of 98°C for 30 sec; 40 cycles of 98°C for 10 sec, 63°C (rs142430606) or 60°C (rs200958270) for 10 sec, 72°C for 45 sec; 1 cycle of 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products were purified using QIAGEN QIAquick PCR purification kit (Valencia, CA) and Sanger sequenced by The University of Chicago DNA sequencing core facility.

Association analysis of rare familial IL17REL variation in sporadic IBD datasets

To determine whether the IL17REL variants identified by familial WES analysis were also associated with sporadic IBD, we tested for allele frequency differences between cases and controls in two large IBD datasets, described below.

Case-Control dataset 1

The first case-control dataset (CC 1) was comprised of 1477 CD cases, 559 UC cases, and 2614 healthy controls, all of Ashkenazi Jewish (AJ) ancestry. The cases and controls were enrolled at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles; University of Toronto; Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York; Yale University; and Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, New York (23, 24). All participants provided written consent for genetic analysis at each participating site, and IBD patients had diagnoses confirmed at each recruiting site by a health care provider, based on standard criteria including clinical presentation, as well as endoscopic, radiologic and/or pathologic confirmation. Participants were validated as being of full AJ ancestry using principal components analysis of 10,313 independent autosomal markers outside established IBD-associated genomic regions in previous genomic scans of AJ and Non-Jewish European-ancestry individuals (4, 23). DNA samples were genotyped using the Illumina HumanExome beadchip v1.0 (Illumina, Inc, San Diego, CA), with custom content comprised of rare exonic variants and known IBD-associated variants. The IL17REL mutations identified by familial WES analysis in this study were directly genotyped on this platform. Genotyping data were generated at three centers (Philadelphia, PA; Manhasset, NY; and Los Angeles, CA) using the same custom genotyping array and called jointly using GenomeStudio version 2011.1 (Illumina, Inc, San Diego, CA). Quality control was performed using SNP metrics based on fluorescent probe intensities and genotype frequencies following guidelines produced by the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genome Epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium (25), as well as by visual inspection of markers with uncertain genotyping quality. Related samples were identified and removed using pairwise identity-by-descent detection in PLINK (URL: http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/contact.shtml; --genome, pi-hat <0.125) (26). Samples with a discrepancy between self-reported sex and genotypic sex were excluded. The final call rate for both rs142430606 and rs200958270 was 0.999.

Case-Control dataset 2

The second case-control dataset (CC 2) was from the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium (EGAS00000000084), and was comprised of 2869 UC cases and 5984 controls from the 1958 British Birth Cohort and the UK National Blood Service control sets (27). Cases and controls were all non-Hispanic white individuals of European ancestry genotyped on the Affymetrix SNP Array 6.0. Genotypes were assigned using the Chiamo calling algorithm (URL: http://mathgen.stats.ox.ac.uk/genetics_software/chiamo/chiamo.html) (27–30). We imputed a 5MB region on chromosome 22 that included rs142430606 and rs200958270. Prior to pre-phasing, PLINK (26) was used to remove SNPs for: 1) overall proportion of samples missing >0.05 (--mind 0.05); 2) minor allele frequency (MAF) <0.01 (--maf 0.01); or 3) Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium P <0.0001 (--hwe 0.0001). Samples were removed for: 1) proportion of missing genotypes (--geno 0.02); 2) unexplained loss of heterozygosity (--het, |F| > 0.05); or 3) excess identity-by-descent (--genome, pi-hat >0.125). Allele assignment was adjusted to be consistent with The 1000 Genomes Project reference files using strand and position files (URL: http://www.well.ox.ac.uk/~wrayner/strand/).

Following QC, 2692 UC cases and 5783 controls remained for association testing. After pre-phasing using ShapeIt2(31), we performed imputation with IMPUTE2 (32), using all samples in the 1000 Genomes reference panel (phase 3) to infer genotypes for both IL17REL variants. The imputation info scores were 0.78 and 0.79 for rs142430606 and rs200958270, respectively, indicating that the imputation quality was very high.

Statistical analysis

The LD (r2) between rs142430606 and rs200958270 was calculated using ldmax (http://csg.sph.umich.edu/abecasis/GOLD/docs/ldmax.html) and all samples from the 1000 Genomes reference panel.

For CC 1, association between disease status and SNP genotype was evaluated using Fisher’s exact test as implemented in PLINK (--fisher) (26).

For CC 2, we used SNPTEST to test for an additive relationship between disease status and SNP genotype. This test accounts for uncertainty in the imputed genotypes (snptest –frequentist 1 –method score) (33).

For CC 1, we adjusted the association p-value (Padj) to account for multiple testing, because we performed tests of association with both UC and CD. For both CC 1 and CC 2, no additional adjustment to the p-value was required for testing two SNPs, because the linkage disequilibrium between rs142430606 and rs20095827 is very high (r2= 0.92), and so the correlation between the two tests is 0.96. P-values are reported as one-sided.

RESULTS

Candidate Rare Variant Discovery in Familial IBD by Whole Exome Sequencing

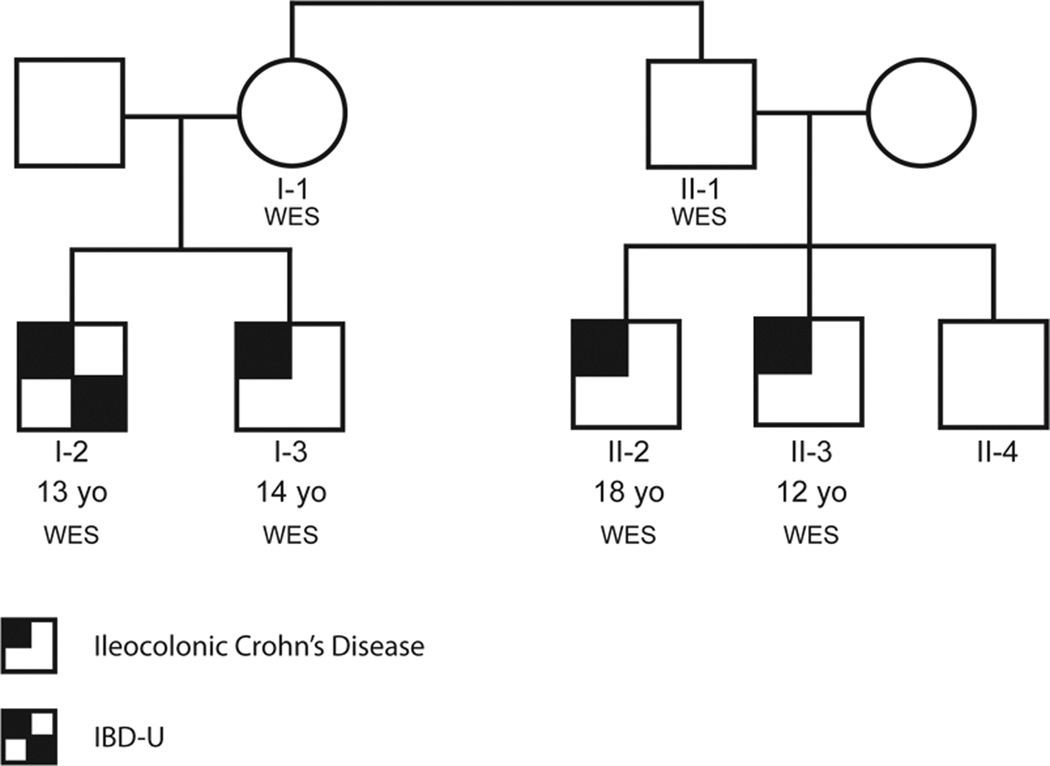

We performed whole exome sequence (WES) analysis on six members of a high-penetrance pediatric IBD family of white, non-Hispanic European ancestry (Figure 1). The four affected individuals are two pairs of siblings who are first cousins (Individuals I-2 and I-3, and II-2 and II-3, respectively), all of whom were diagnosed with pediatric-onset IBD, primarily involving the colon. Individuals I-2 and I-3 were diagnosed at 13 and 14 years of age with colon-only disease (IBD-U) and Crohn’s ileocolitis, respectively. Individual II-2 was diagnosed with ileocecal CD at age 18; Individual II-3 was diagnosed with ileocolonic CD at age 12. Individual II-4 (not sequenced) is the 21 year old sibling of Individuals II-2 and II-3, and was diagnosed after ileo-colonoscopy at age19 with post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome, diarrhea predominant (IBS-D), with normal histology. Individuals I-1 and II-1 are full siblings, aged 56 and 55, respectively, who do not have IBD. Individual I-1 is the mother of affected Individuals I-2 and I-3, and Individual II-1 is the father of affected Individuals II-2 and II-3 and unaffected Individual II-4.

Figure 1. IBD Family pedigree.

Two unaffected siblings (Individuals I-1 and II-1) and their affected children (Individuals I-2 and I-3, who are full siblings, and Individuals II-2 and II-3, who are full siblings) were analyzed by WES. Individual I-2 was diagnosed at 13 years of age as IBD-U, with only colon affected and no terminal ileitis (TI). Reticulum stress was visually normal but biopsies revealed inflammation with active segment of visual inflammation 35–50 cm. Individual I-3 was diagnosed at 14 years of age with ileocolonic CD with granulomas. Individual II-2 was diagnosed with ileocolonic CD at 18 years of age. Individual II-3 was diagnosed with ileocolonic CD at 12 years of age. Individual II-4 is 21 years of age, and was diagnosed at age 19 with post-infectious IBS with normal ileocolonoscopy biopsies.

Following WES and QC, we found that for each individual sequenced, at least 98.6% of the exome was covered at 5x and 80.0% at 20x, with average coverage depth across the exome of 50x or greater (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, which shows exome coverage for each individual sequenced). Variants with low quality scores and those not called by at least two genotype callers using alignments from at least two aligners were removed. Functional categories of the variants identified in each individual are summarized in Table, Supplemental Digital Content 4.

We assumed that the clustering of IBD in this family was at least partially because all affected children share the same rare deleterious variant(s) inherited from their obligate-carrier parents, Individuals I-1 and II-1. Since the parents do not have IBD, we also assumed that this shared variant is incompletely penetrant for IBD.

Among the four affected children, we identified a total of 1622 rare variants, defined as variants with a MAF <0.01 in the 1000 Genomes (18) and ESP databases. Of these, 173 were shared among all four affected children, and 156 were common to all six sequenced individuals (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 5, which lists all 156 rare variants shared by all six family members). Variants were categorized as: non-frameshift insertion/deletions (n=53), non-synonymous single nucleotide variants (SNVs, n=51), frameshift insertion/deletions (n=31), stop gain (n=1), and unannotated (n=20). Of these 156, only 25 variants were predicted to be either deleterious or probably deleterious by either SIFT or Polyphen-2 (Table 1) (20, 21).

Table 1.

List of rare variants predicted to be deleterious that are shared by all members of the family

| Gene | Chr | Position | Ref Allele | Alt Allele | rsID | AA Change | MAF 1000Genomes (EUR) |

MAF ESP6500 (EUR) |

SIFT | Polyphen2 | Zygosity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-1 | I-2 | I-3 | II-1 | II-2 | II-3 | |||||||||||

| BCLAF1 | 6 | 136590698 | C | T | rs62431287 | p.R697H | NA | NA | D | P | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| CABYR | 18 | 21736505 | T | C | rs138431678 | p.V329A | 0.0040 | 0.0036 | D | NA | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| CPXM1 | 20 | 2781101 | A | C | NA | p.S40A | NA | NA | T | P | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| FKRP | 19 | 47259734 | G | C | NA | p.E343Q | NA | NA | D | D | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| GPRIN2 | 10 | 46999151 | T | C | rs3127820 | p.W91R | NA | NA | D | B | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| GPRIN2 | 10 | 46999178 | A | C | rs7090312 | p.T100P | NA | NA | D | P | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| HRNR | 1 | 152187562 | A | C | rs61814936 | p.H2181Q | NA | NA | D | NA | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| IL17REL | 22 | 50436488 | G | A | rs142430606 | p.P262L | 0.0066 | 0.0069 | T | D | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| IL17REL | 22 | 50438279 | T | C | rs200958270 | p.E151G | 0.0040 | 0.0042 | D | D | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| KCNJ18 | 17 | 21319543 | G | A | rs80335301 | p.V297I | NA | NA | D | P | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| KCNJ18 | 17 | 21319786 | G | A | rs78547883 | p.E378K | NA | NA | D | P | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| KCNJ18 | 17 | 21319868 | G | T | rs73979902 | p.S405I | NA | NA | D | B | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| MAGEC1 | X | 140993852 | C | G | rs176038 | p.T221S | NA | NA | D | NA | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| MAGEC1 | X | 140993859 | T | A | rs6634333 | p.S223R | NA | NA | D | NA | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| MAGEC1 | X | 140993864 | T | C | rs34836042 | p.F225S | NA | NA | D | NA | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| MLL3 | 7 | 151945204 | G | A | rs4024453 | p.S772L | NA | NA | D | P | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| MLL3 | 7 | 151970856 | T | A | rs10454320 | p.T316S | NA | NA | T | P | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| NSFL1C | 20 | 1433259 | G | A | rs145945037 | p.L191F | 0.0053 | 0.0040 | D | D | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| PABPC1 | 8 | 101721812 | G | A | rs200409148 | p.R374C | NA | NA | D | D | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| PCMTD1 | 8 | 52733228 | G | A | rs73592211 | p.R253C | NA | NA | D | P | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| PDE4DIP | 1 | 144871755 | A | T | rs1778159 | p.V1736E | NA | NA | D | B | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| PIGU | 20 | 33233137 | G | A | NA | p.T66I | NA | NA | D | D | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| RRBP1 | 20 | 17600347 | C | G | NA | p.E769D | NA | NA | T | D | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| TCEB3CL | 18 | 44555312 | G | C | rs2510019 | p.S301C | NA | NA | D | P | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| TGM6 | 20 | 2413163 | G | C | rs138807504 | p.G621R | 0.0013 | 0.0023 | D | P | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

Indicates heterozygous

Indicates homozygous

All SNP are non-synonymous

NA, not available; B, benign; D, deleterious; P, probably deleterious; T, tolerated

To prioritize among these 25 variants, we determined the subset found in IBD-associated genes (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which lists known IBD-associated genes). This reduced the list to only two variants, both located within IL17REL, and separated by 1791 nucleotides. The rare allele of the first variant, rs200958270 (c.452a>g), was observed once in 536 European chromosomes in the 1000 Genomes database and results in a glutamic acid to glutamine change at amino acid 151, a position highly conserved in mammals. The rare allele of the second variant, rs142430606 (c.785a>t), was also observed only once, on the same chromosome as the rare allele of rs200958270, and results in a proline to leucine change at position 262, a residue that is also highly conserved (34). All six family members were heterozygous for both variants. The genotypes of both variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing with 100% concordance.

Rare Variant Association Testing in Non-Familial IBD

Although these IL17REL variants are very rare, they are not unique to this family, suggesting that they may predispose to IBD not only in this high-penetrance family, but in other patients with IBD as well. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the allele frequencies of both IL17REL variants in two large independent IBD case-control (CC) sets.

In the first (CC 1), we directly genotyped both variants in 1477 CD cases, 559 UC cases, and 2614 healthy controls, all of AJ ancestry, using a custom Illumina BeadChip. We found that rs142430606 was significantly associated with UC (OR=2.99, Padj=0.028; MAFcases=0.0063, MAFcontrols=0.0021), and rs200958270 was marginally associated (OR=2.61, Padj=0.082; MAFcases=0.0045, MAFcontrols=0.0017) (Table 2). The risk alleles were also more common in CD cases than controls, but neither association was statistically significant (rs142430606: OR=1.29, Padj=0.54; rs200958270: OR=1.58, Padj=0.39). Linkage disequilibrium between these two SNPs was too great (r2=0.92) to determine whether one or the other variant, or both variants independently, is driving the association and is putatively functional.

Table 2. Association results between IBD and the familial-IBD predisposing IL17REL variants in CC 1.

Association results for rs142430606 and rs200958270 in CD (1477 cases and 2614 controls) and UC (559 UC cases and 2614 controls). All cases and controls are of AJ ancestry.

| Crohn’s Disease | Ulcerative Colitis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Case MAF |

Control MAF |

OR (SE) |

Punadj (exact) |

Padj (exact)* |

Case MAF |

Control MAF |

OR (SE) |

Punadj (exact) |

Padj (exact)* |

| rs142430606 | 0.0027 | 0.0021 | 1.29 (0.47) |

0.32 | 0.54 | 0.0063 | 0.0021 | 2.99 (0.48) |

0.014 | 0.028 |

| rs200958270 | 0.0027 | 0.0017 | 1.58 (0.49) |

0.22 | 0.39 | 0.0045 | 0.0017 | 2.61 (0.56) |

0.042 | 0.082 |

Padj is the P-value after adjusting for performing tests in both Crohn’s Disease and UC

We then investigated the association between these variants and UC in an independent case-control dataset (CC 2) from the Wellcome Trust Case-Control Consortium 2 (WTCCC2) project. Following QC, we analyzed 2692 UC cases and 5783 controls. Using data from The 1000 Genomes Project, we imputed the 5Mb region surrounding the variants, and then tested both SNPs for association with UC. The imputation info score was 0.78 for rs142430606, and 0.79 for rs200958270, indicating that each variant was imputed with high confidence. Again, we found that both rs142430606 (OR=1.94, P=0.0056; MAFcases=0.0071, MAFcontrols=0.0045) and rs200958270 (OR=2.08, P=0.0028; MAFcases=0.0071, MAFcontrols=0.0042) were associated with UC (Table 3). Importantly, these results retained significance after incorporating the uncertainty inherent in testing associations using imputed genotypes.

Table 3. Association results between UC and the familial-IBD predisposing IL17REL variants in CC 2.

Replication results for rs142430606 and rs200958270 in UC (2692 cases and 5783 controls). All cases and controls are of European non-Hispanic ancestry.

| Ulcerative Colitis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Case MAF | Control MAF | OR (SE) | p-value |

| rs142430606 | 0.0071 | 0.0045 | 1.94 (0.51) | 0.0056 |

| rs200958270 | 0.0071 | 0.0042 | 2.08 (0.55) | 0.0028 |

Taken together, our data identifies two novel rare risk alleles for inflammatory bowel disease and further implicate IL17REL as an important susceptibility locus for these common and debilitating conditions.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we discovered two rare deleterious variants in IL17REL by WES of a multiplex family with early-onset IBD. By assuming a significant shared genetic component of susceptibility among affected family members, we propose that these variants are associated with increased risk for IBD in this family. We then demonstrated an association between these variants and IBD in two independent case-control studies of sporadic UC. Because the variants are in strong linkage disequilibrium, they reflect a single association signal, and so, it is not possible to determine which variant is likely to be causal. Although we identified 24 other rare deleterious variants shared among all six sequenced family members, we prioritized for association testing the variants in IL17REL because prior evidence indicated that variation in this gene is associated with IBD risk.

It is of interest to note that the IL17REL mutations we found are significantly associated with UC but not CD, and that although the affected individuals in the family sequenced were diagnosed with CD, all had predominant features of colitis. IL17REL is a homolog of IL17RE, a member of the IL17R family that functions in the IL17 pathway to initiate the Th2-mediated immune response (35),(36). Reynolds et al. studied dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in Il17c−/− mice and noted intestinal wall thickening and increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the Il17c–deficient mice as compared to WT controls (37). They further demonstrated that ectopic expression of Il17c in YAMC, a colon epithelial cell line endogenously expressing Il17re, resulted in increased expression of Occludin, Claudin1 and Claudin4, genes involved in tight junction function, thereby suggesting that the IL17C–IL17RE complex may play a role in maintaining mucosal barrier integrity. The two IL17REL risk alleles encode residues (Gln151 and Leu262) in regions of highly conserved secondary structure, suggesting that they may alter protein function, perhaps by interfering with oligomerization of IL17REL with other IL17R family members, such as IL17C. In light of the likely role of IL17REL in the IL17 pathway, it is tempting to speculate that Individual I-1 did not develop IBD because she is the only family member sequenced who also carries a variant in IL23R, rs11209026, which has previously been shown to protect against IBD by negatively regulating IL17 signaling (28).

Although the genetic analysis of families has led to the identification of many rare or familial variants that are completely or nearly completely penetrant, the discovery of rare incompletely penetrant variants remains challenging and inefficient (38–44), largely because the unbiased canvassing of the entire exome or genome results in the performance of an enormous number of tests of association. As a result, the p-value threshold for significance must be adjusted to account for this large number of tests, with the inevitable consequence that even extremely large studies are underpowered to detect rare variants. As an alternative strategy, we used WES of a single family to guide the discovery of two rare variants, which we then tested for association with IBD in two large case-control datasets. Thus, by taking advantage of family structure and prior knowledge of IBD etiology, our strategy successfully identified two new rare variants associated with UC. This method of using families to substantially reduce the number of hypotheses tested in genetic studies of rare variation may be of importance not only for IBD, but also for other genetically complex disorders. Recently, a similar strategy was attempted unsuccessfully for autism spectrum disorder, but successfully for breast cancer (45, 46). It is important to note that whereas there are precedents for moderate- and high-penetrance susceptibility alleles for breast cancer in genes such as BRCA1, BRCA2 and CHEK2, few such examples exist for autism spectrum disorder, and they are similarly lacking in IBD.

As was recently demonstrated, it is unlikely that rare variants contribute significantly to the missing heritability for most complex disorders (47). For specific patient subsets, however, rare variants are likely to be exceedingly important, as in patients with germline high-penetrance BRCA mutations. Additionally, the discovery of moderate- and high-penetrance mutations has shed considerable mechanistic light on the etiology of diseases such as breast cancer. Thus, there is a compelling rationale for investigating highly familial occurrences of complex diseases. The critical question is how to distinguish families that are genetically loaded because of high-penetrance susceptibility alleles from those that are genetically loaded because of a high polygenic burden of common variants and those that are apparently genetically loaded because of shared exposures. For most complex traits, the occurrence of familial aggregates of affected individuals due to chance is not uncommon. IBD is diagnosed across the entire age spectrum and is more common in AJ’s than in non-Jews. Therefore, a non-AJ family in which multiple individuals are diagnosed with IBD under the age of 15 and all affected individuals share the same disease phenotype -- non-UC IBD with features of colitis -- is unusual and potentially suggestive of a family in which the IBD-predisposing genetic contribution to risk is not polygenic, but is instead the result of a small number of higher penetrance risk variants.

One intriguing future study would be to investigate the role of the IL17REL variants we identified in the context of the previously identified polygenic risk for IBD. Because our data suggests that the relative importance of the IL17REL variants is high in this family, it might be predicted that the burden of IBD-associated common variation would be lower in affected individuals than is typically observed in non-familial patients. Similarly, it might be predicted that controls harboring the rare IL17REL alleles would have an even lower burden of common variation than those homozygous for the common alleles.

Although both IL17REL variants we identified are of moderate-penetrance, a provocative hypothesis emerging from our study is that they may identify a subset of IBD patients at risk for high-penetrance familial disease. Suggesting this is the example of the role of the CHEK2*1100delC variant in familial breast cancer risk. Several large studies have demonstrated that in patients not selected for a family history of breast cancer, the OR for this variant ranges from 1.41–3.6. In contrast, in breast cancer patients with at least one other affected family member, the OR was 4.8–5, and in those with both a first- and a second-degree relative, it was 7.3 (48–50). In the two IBD CC datasets we investigated, the OR for each of the IL17REL variants was 1.94–2.99 for cases unselected for family history. Given that these variants were originally discovered by WES of a family selected for analysis because of high-penetrance IBD, it would be of tremendous interest to determine whether the odds ratios for these variants differed as a function of family history of IBD, and to calculate the lifetime risk for IBD in carriers of the IL17REL risk alleles stratified by family history. It may be that IL17REL mutation status could potentially be of great clinical utility for unaffected individuals with a family history of IBD.

In conclusion, these results demonstrate that families with uncommon presentations of common diseases, such as pediatric-onset IBD, may provide important clues to the existence of moderate- or high-penetrance rare variants associated with complex diseases. They suggest that our novel approach of intersecting WES analysis of high-penetrance families with association testing in large case-control datasets represents a powerful, efficient, and relatively low-cost strategy to discover rare disease-associated variants, a category of genetic variation currently refractory to investigation in most human diseases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HD0433871, CA129045 and CA40046 to KO; U01 DK62429, U01 DK62422, R01 DK092235 to JHC); SUCCESS (IP, JHC); the American Cancer Society – Illinois Division (KO); the New York Crohn’s Foundation (IP); and the Cancer Research Foundation (KO). We are also grateful for the financial support of the Barnett and Alscher families of Chicago (BSK). The Center for Research Informatics is funded by the Biological Science Division and The Institute for Translational Medicine/CTSA (NIH UL1 RR024999) at The University of Chicago.

We thank MP Tierney and T Mangatu for their superb technical assistance; E Bartom for development of the WES analysis pipelines; M Jarsulic for technical assistance with the pipelines; and J Andrade for many invaluable discussions. We are especially grateful for the contributions of the many participating patients, without whom this work would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson CA, Boucher G, Lees CW, et al. Meta-analysis identifies 29 additional ulcerative colitis risk loci, increasing the number of confirmed associations to 47. Nat Genet. 2011;43:246–252. doi: 10.1038/ng.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franke A, McGovern DP, Barrett JC, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn's disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1118–1125. doi: 10.1038/ng.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goyette P, Boucher G, Mallon D, et al. High-density mapping of the MHC identifies a shared role for HLA-DRB1*01:03 in inflammatory bowel diseases and heterozygous advantage in ulcerative colitis. Nat Genet. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ng.3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119–124. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Do R, Stitziel NO, Won HH, et al. Exome sequencing identifies rare LDLR and APOA5 alleles conferring risk for myocardial infarction. Nature. 2015;518:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature13917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Purcell SM, Moran JL, Fromer M, et al. A polygenic burden of rare disruptive mutations in schizophrenia. Nature. 2014;506:185–190. doi: 10.1038/nature12975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott-Van Zeeland AA, Bloss CS, Tewhey R, et al. Evidence for the role of EPHX2 gene variants in anorexia nervosa. Molecular psychiatry. 2014;19:724–732. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novoalign Reference Manual. 2014 Available at: http://www.novocraft.com/documentation/novoalign-2/novoalign-reference-manual/.

- 11.Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:841–842. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Picardtools MarkDuplicates Program. Available at: http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/

- 13.Challis D, Yu J, Evani US, et al. An integrative variant analysis suite for whole exome next-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garrison E, Marth G. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 15.DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Genomes Project C, Abecasis GR, Auton A, et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christodoulou K, Wiskin AE, Gibson J, et al. Next generation exome sequencing of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease patients identifies rare and novel variants in candidate genes. Gut. 2013;62:977–984. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenny EE, Pe'er I, Karban A, et al. A genome-wide scan of Ashkenazi Jewish Crohn’s disease suggests novel susceptibility loci. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang W, Hui KY, Gusev A, et al. Extended haplotype association study in Crohn's disease identifies a novel, Ashkenazi Jewish-specific missense mutation in the NF-kappaB pathway gene, HEATR3. Genes Immun. 2013;14:310–316. doi: 10.1038/gene.2013.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grove ML, Yu B, Cochran BJ, et al. Best practices and joint calling of the HumanExome BeadChip: the CHARGE Consortium. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Consortium UIG. Barrett JC, Lee JC, et al. Genome-wide association study of ulcerative colitis identifies three new susceptibility loci, including the HNF4A region. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1330–1334. doi: 10.1038/ng.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duerr RH, Taylor KD, Brant SR, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 2006;314:1461–1463. doi: 10.1126/science.1135245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rioux JD, Xavier RJ, Taylor KD, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for Crohn disease and implicates autophagy in disease pathogenesis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:596–604. doi: 10.1038/ng2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silverberg MS, Cho JH, Rioux JD, et al. Ulcerative colitis-risk loci on chromosomes 1p36 and 12q15 found by genome-wide association study. Nat Genet. 2009;41:216–220. doi: 10.1038/ng.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delaneau O, Marchini J, Zagury JF. A linear complexity phasing method for thousands of genomes. Nat Methods. 2012;9:179–181. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, et al. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat Genet. 2012;44:955–959. doi: 10.1038/ng.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, et al. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:906–913. doi: 10.1038/ng2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franke A, Balschun T, Sina C, et al. Genome-wide association study for ulcerative colitis identifies risk loci at 7q22 and 22q13 (IL17REL) Nat Genet. 2010;42:292–294. doi: 10.1038/ng.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu B, Jin M, Zhang Y, et al. Evolution of the IL17 receptor family in chordates: a new subfamily IL17REL. Immunogenetics. 2011;63:835–845. doi: 10.1007/s00251-011-0554-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaffen SL. Structure and signalling in the IL-17 receptor family. Nature reviews Immunology. 2009;9:556–567. doi: 10.1038/nri2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reynolds JM, Martinez GJ, Nallaparaju KC, et al. Cutting edge: regulation of intestinal inflammation and barrier function by IL-17C. Journal of immunology. 2012;189:4226–4230. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Auer PL, Teumer A, Schick U, et al. Rare and low-frequency coding variants in CXCR2 and other genes are associated with hematological traits. Nat Genet. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ng.2962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beaudoin M, Goyette P, Boucher G, et al. Deep resequencing of GWAS loci identifies rare variants in CARD9, IL23R and RNF186 that are associated with ulcerative colitis. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonnefond A, Clement N, Fawcett K, et al. Rare MTNR1B variants impairing melatonin receptor 1B function contribute to type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2012;44:297–301. doi: 10.1038/ng.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diogo D, Kurreeman F, Stahl EA, et al. Rare, low-frequency, and common variants in the protein-coding sequence of biological candidate genes from GWASs contribute to risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Gudbjartsson DF, et al. A study based on whole-genome sequencing yields a rare variant at 8q24 associated with prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1326–1329. doi: 10.1038/ng.2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johansen CT, Wang J, Lanktree MB, et al. Excess of rare variants in genes identified by genome-wide association study of hypertriglyceridemia. Nat Genet. 2010;42:684–687. doi: 10.1038/ng.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rivas MA, Beaudoin M, Gardet A, et al. Deep resequencing of GWAS loci identifies independent rare variants associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1066–1073. doi: 10.1038/ng.952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inoue E, Watanabe Y, Egawa J, et al. Rare heterozygous truncating variations and risk of autism spectrum disorder: Whole-exome sequencing of a multiplex family and follow-up study in a Japanese population. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015 doi: 10.1111/pcn.12274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiiski JI, Pelttari LM, Khan S, et al. Exome sequencing identifies FANCM as a susceptibility gene for triple-negative breast cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:15172–15177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407909111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gusev A, Lee SH, Trynka G, et al. Partitioning heritability of regulatory and cell-type-specific variants across 11 common diseases. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95:535–552. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cybulski C, Wokolorczyk D, Jakubowska A, et al. Risk of breast cancer in women with a CHEK2 mutation with and without a family history of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3747–3752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meijers-Heijboer H, van den Ouweland A, Klijn J, et al. Low-penetrance susceptibility to breast cancer due to CHEK2(*)1100delC in noncarriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Nat Genet. 2002;31:55–59. doi: 10.1038/ng879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weischer M, Bojesen SE, Ellervik C, et al. CHEK2*1100delC genotyping for clinical assessment of breast cancer risk: meta-analyses of 26,000 patient cases and 27,000 controls. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:542–548. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.