Abstract

Genomic imprinting is a genetic process where only one allele of a particular gene is expressed in a parent-of-origin dependent manner. Epigenetic changes in the DNA, such as methylation or acetylation of histones, are primarily thought to be responsible for silencing of the imprinted allele. Recently, global CpG methylation changes have been identified in psoriatic skin in comparison to normal skin, particularly near genes known to be upregulated in psoriasis such as KYNU, OAS2, and SERPINB3. Furthermore, imprinting has been associated with multi-chromosomal human disease, including diabetes and multiple sclerosis. This paper is the first to review the clinical and genetic evidence that exists in the literature for the association between imprinting and general skin disorders, including atopic dermatitis and psoriatic disease. Atopy was found to have evidence of imprinting on chromosomes 6, 11, 14, and 13. The β subunit of the IgE receptor on chromosome 11q12-13 may be imprinted. Psoriatic disease may be related to imprinting effects on chromosome 6 for psoriasis and 16 for psoriatic arthritis.

Introduction

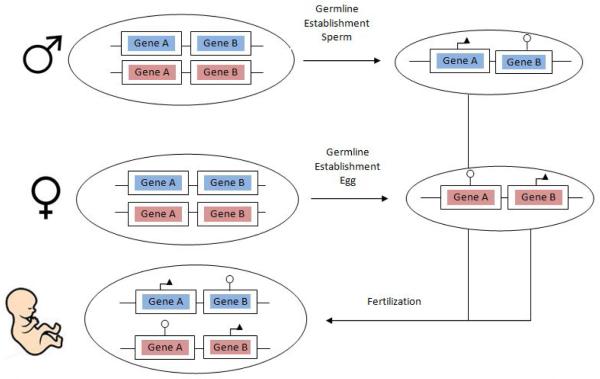

Genomic imprinting occurs when only one allele of a particular gene is expressed in a parent-of-origin dependent manner.[1] (Figure 1) The “imprinted” allele refers to the allele that has been silenced, either the maternal allele or paternal allele. In mammals, imprinting affects only a small fraction of the total number of genes. In humans, it is estimated that there are at least 79 imprinted genes, although some studies suggest the number may be higher up to 300 genes.[2] However, imprinting of certain human genes is a required and normal part of embryologic development.

Figure 1. Schematic for Genomic Imprinting.

Imprinting occurs when there is preferential parental expression of a chromosome or gene. Gene A (e.g. psoriasis gene such as HLA or CARD14) is depicted here to have preferential paternal expression, denoted with an arrow, and maternal silencing denoted with a circle. Gene B (e.g. atopic dermatitis gene such as filaggrin) is depicted here to have preferential maternal expression.

Imprinting is largely thought to occur through the epigenetic mechanisms of DNA and histone methylation, where epigenetics refers to chemical modifications (e.g. methylation) of DNA or DNA-associated proteins that alter gene expression without a change in the genetic code.[3] In imprinting these epigenetic marks are made in the paternal sperm or maternal egg cells and are maintained through mitotic cell divisions in the somatic cells of an organism. The DNA sequences affected by these epigenetic modifications are known as “differentially methylated regions,” or DMR.[4]

Genomic imprinting can be considered a specific subset of the more general phenomenon of allele-specific expression (ASE). ASE occurs when two alleles of the same gene have different levels of expression, ranging from slight differences in expression to one allele expressed while the other is completely silenced. The most common form of ASE is the first situation, in which both alleles of a gene are expressed, but one allele more so than another. In this case the differential gene expression typically results from either genetic or epigenetic changes specific for a particular allele, and expression levels are unrelated to the parental origin of the allele. In contrast, imprinting occurs in the second situation of all-or-none expression and is dependent only on the parental origin of the allele, not on its allelic DNA sequence.

Imprinting is important because of its association with human disease. Both single chromosome and multi-chromosome diseases have been implicated in imprinting. Examples of single chromosome diseases affected by imprinting include Beckwith-Wiedmann, Prader-Willi, and Angelman syndrome.[5] Moreover, imprinting has been explored for complex diseases involving multiple chromosomes, such as diabetes and multiple sclerosis. Similar to psoriasis, multiple sclerosis susceptibility is associated with genetic polymorphism with the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region on chromosome 6.[6] Through HLA genotyping, it was found that the major susceptibility haplotype HLA-DRB1 had a maternal preference of inheritance.[6] Similarly, a genome-wide association (GWA) study has suggested a paternal bias in inheritance for risk of type of diabetes, related to the imprinting effects of the gene DLK1.[7] Recently, epigenetics has been explored in the realm of common skin disorders, such as atopic dermatitis (AD) and psoriatic disease, which are known to have a genetic basis. Global CpG methylation changes have been identified in psoriatic skin in comparison to normal skin, particularly near genes known to be upregulated in psoriasis such as KYNU, OAS2, and SERPINB3.[8]

This article is the first to review the literature on genomic imprinting in psoriatic disease and AD. We aim to explore whether imprinting may play a role in the pathogenesis of psoriatic disease and AD, possibly leading to new avenues for future research.

Methods

A Pubmed search using the terms (“imprinting” AND (“psoriasis” OR “eczema” OR “atopic dermatitis” OR “psoriatic arthritis”)) was conducted on February 2015. Results included 17 articles. The abstract of each article was reviewed for relevance. References of selected articles were also reviewed . In addition, a Pubmed search using the terms (“imprinting” AND “atopy”) was conducted due to the inclusion of atopic dermatitis in the definition of general atopy. Results included 13 articles, which were screened for relevance via their abstracts.

Results

I. Atopy in Relation to Atopic Dermatitis

A. Clinical Evidence

A number of studies have supported a possible role for imprinting in atopic disease by examining whether the presence of maternal or paternal atopy affects risk of atopy development in children. In 2012, Folsgaard et al. collected the upper airway mucosal lining fluid and quantified levels of 18 cytokine and chemokine mediators of atopy, including IFN-gamma, IL-2, and TNF-α, from 309 asymptomatic neonates.[9] Among them, 241 neonates had either a mother or father with history of atopy, which included atopic dermatitis, asthma, and hay fever. Neonates of atopic mothers and non-atopic fathers had lower levels of mediators in the blood when compared neonates of atopic fathers and non-atopic mothers (P =0.02). Overall, it was found that healthy neonates born to mothers who are atopic have downregulated cytokines and chemokines in the upper airway mucosal lining fluid, and that paternal atopy status did not have any effect on the neonate. The authors suggested that maternal atopy may delay the maturation of the upper airway immune response in neonates, which paradoxically could lead to increased risk of atopy later in life.

In 1996, Johnson et al. analyzed cord blood from 777 newborns for IgE levels and family history of atopy, which included allergies, hay fever, and asthma.[10] Maternal, but not paternal, history of atopic disease was associated with an elevated IgE. Lastly, Ruiz et al. evaluated infantile AD by parental origin of atopy.[11] Of the 39 infants affected by AD, 19 had atopic mothers and 20 had atopic fathers. Of the 19 with atopic mothers, 9 had AD whereas of the 20 with atopic fathers, only 2 were affected (relative risk = 4.7 [95% confidence interval 2.5 to 9.0], P = 0.023). Furthermore, 7 of the 19 infants with atopic mothers had AD before 6 months of age compared to none of the infants with atopic fathers (P = 0.007). The authors concluded that maternal atopy poses a higher risk for infantile AD than paternal atopy.

B. Genetic Evidence

Furthermore, a number of additional atopy studies have investigated possible genetic loci involved in imprinting. Shirakawa et al. studied Japanese families with atopy (allergic asthma and rhinitis) and had findings supportive of imprinting.[12] Four large families had a genetic linkage analysis completed. Of these, two families demonstrated close genetic linkage of atopy and maternal inheritance of the high affinity IgE receptor B chain on chromosome 11q (LOD = 9.35). This suggested possible imprinting of chromosome 11q13 affecting atopy. Similarly, Cookson et al. studied siblings-pairs and found that 62% of sibling-pairs affected by atopy shared the maternal 11q13 allele while only 46% shared the paternal 11q13 allele (P=0.001), suggesting either paternal imprinting at 11q13 or maternal modification of developing immune responses.[13] Furthermore, a parametric and nonparametric multimarker linkage analysis of the Busselton families on the trait of atopy and asthma suggested imprinting effects on chromosome 6 and 14.[14] Demenais et al. used an affected sib-pair (ASP) method to study atopy in the Busselton nuclear families that showed significant excess of sharing of a cluster of paternal alleles as compared with maternal allele on chromosome 13.[15]

In contrast, we identified one genetic study that did not find evidence of imprinting in atopy. Ferreira et al. studied the genetics of 38 unrelated atopic cases and 37 controls.[16] Atopy was defined as a positive skin prick test. The methylation state of the promoter region of MS4A2, a candidate imprinting gene thought to increase the risk of atopy, and of the AluSp repeat, a potential locus of epigenetic regulation of MS4A2, were evaluated. It was found that AluSp was highly methylated regardless of atopy status, and thus not imprinted. The promoter region for MS4A2 had lower levels of methylation when compared to AluSp but there was no evidence of parental imprinting or allele-specific methylation at the promoter site.

II. Atopic Dermatitis

When the literature was examined specifically atopic dermatitis, fewer studies were identified. Cox et al. studied the β subunit for a high-affinity IgE receptor on chromosome 11q12-13 which was associated with AD.[17] A genotype analysis 60 families with a history of AD was conducted. Rsa1 polymorphisms within the receptor gene were associated with AD, with an excess sharing of maternally-derived alleles (P = 0.0002 for allele 2 of Rsa1 intron 2 and P = 0.00034 for allele 1 of Rsa1 exon 7). Transmission of receptor alleles to offspring with AD was found to be almost exclusively through the maternal line. However, Yotsumoto et al. had opposite findings when studying the same β subunit for high-affinity IgE receptor in mice.[18] In measuring the allele specific expression of MS4A2, the gene responsible for the β subunit of the IgE receptor, it was found that both maternal and paternal alleles were expressed equally.

In 2000, Lee et al. performed a genome-wide linkage study on 199 families with at least 2 siblings affected by AD.[19] There was highly significant evidence for linkage on chromosome 3q21 suggestive of paternal imprinting (P = 8.42×10−6).

III. Psoriasis

Two studies were identified examining the possible evidence of imprinting in psoriasis. In 1992, Traupe et al. found that children with fathers with psoriasis are 270g heavier than children from mothers with psoriasis (P<0.004).[20] Offspring from fathers with psoriasis and male “gene carriers” were significantly more often affected than the offspring of mothers with psoriasis and female “gene carriers” (P<0.015 and P<0.007, respectively). 65% of grandchildren with psoriasis had an affected grandfather whereas only 35% had an affected grandmother (P<0.04). Burden et al. conducted a survey and linkage analysis on 1,250 subjects with psoriasis.[21] Analysis was completed on chromosomes 17q, 4q, and 6p. There was evidence of a parental effect: more subjects had an affected father than an affected mother (P= 0.044), as well as strong evidence for linkage on chromosome 6p (LOD=4.63) with greatest evidence of linkage when the allele was of paternal origin (P=0.00083). Genetic anticipation was also studied and found to be most marked if psoriasis was inherited from the father; the mean age of onset in the offspring was 24.1 years younger than in the affected father compared to 10.9 years younger than in the affected mother (P= 0.009).

IV. Psoriatic Arthritis

A. Clinical Evidence

In 2000, Rahman et al. studied 508 patients with psoriatic arthritis, and recorded a detailed family history consisting of a parental history of psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis.[22] Second-degree relative disease history and offspring were also evaluated. Of those with psoriasis, 65% had an affected father and 35% had an affected mother (P= 0.001), while 16.2% of offspring from a father with psoriatic arthritis had psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis compared to 8.3% of offspring from a mother with psoriatic arthritis (P= 0.10). 7% of patients had an affected 2nd degree relative but no affected 1st degree relative. 62% of these had disease from the paternal side of the family. It was suggested that the potential role of a 2nd degree relative supports the hypothesis that the environment is less likely to play a role in diseases pathogenesis, and that genetics play a more prominent role. The results were supportive of excess paternal transmission.

B. Genetic Evidence

In 2003, Karason et al. genotyped and analyzed 178 patients with psoriatic arthritis using a fluorescent labeled microsatellite screening set.[23] The findings supported the recent epidemiological observation that paternal imprinting might play a role in psoriatic arthritis at a molecular genetic level. The linkage analysis, when conditioned for paternal transmission to affected individuals, gave a LOD score of 4.19 (very significant), whereas a LOD score of only 1.03 was observed when conditioned for maternal transmission. A suggestive locus on chromosome 16q was identified. The data indicated that a gene at this locus may be involved in paternal transmission of psoriatic arthritis.

To further this analysis, Giardina et al. studied polymorphisms of CARD15 polymorphisms, the gene located on the section of chromosome 16 suggested by Karason et al. to be imprinted.[24] Genotypic and allelic frequencies were studied in 193 Italian psoriatic arthritis patients and 150 controls. However, no significant differences in CARD15 polymorphisms between psoriatic arthritis patients and controls was found, as well as no evidence of genetic linkage. It was suggested that the results obtained by Karason et al. may differ due to his study of a genetically isolated population and potential founder effect.

Discussion

Genetic involvement in both psoriasis and AD has been well studied. For AD, genetic changes affecting the immune response and the skin barrier have been shown to affect the risk of developing the disease. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in the filaggrin gene and genetic variants in the IL-4 immune response have been shown to increase the risk of AD in children.[25, 26] In psoriasis, specific genetic alleles have been associated with the type of psoriasis seen and the age of onset.[26-28] Generalized pustular psoriasis and psoriasis vulgaris are associated with different genetic variants, supporting the strong genetic involvement in pathogenesis.[29]

Few studies have been conducted studying the possible relation between genomic imprinting and psoriasis and AD. Of those in the literature, there still remains conflicting evidence. Atopy has shown evidence of imprinting on chromosomes 6, 11, 14, and 13.[13-15] There still remains debate on whether the β subunit of the IgE receptor on chromosome 11q12-13 is imprinted. Shirakawa et al. and Cox et al. showed a positive maternal transmission(possible paternal imprinting) of the subunit in allergic rhinitis/asthma and AD families, respectively, whereas Yotsumoto et al. and Ferrerira et al., through MS4A2 analyses, did not find evidence of imprinting.[12, 16-18] Possible involvement of imprinting on chromosome 3 in AD has been noted from genome-wide linkage studies.[19]

In contrast, there is stronger evidence for imprinting in psoriatic disease, particularly in relation to chromosome 6 for psoriasis and 16 for psoriatic arthritis.[21, 23] However, the specific analysis of the gene CARD15 on chromosome 16 did not support any genetic linkage to psoriatic arthritis. This does not exclude the possibility of imprinting effects on chromosome 16, since imprinting is rarely localized to a single gene. The findings of Burden et al. suggesting imprinting effects on chromosome 6 for psoriasis opens up a potential future area of study on the HLA region, which resides on chromosome 6 and is linked to increased susceptibility for the disease.[30] Furthermore, previous imprinting studies of HLA-DRB1 in multiple sclerosis, another autoimmune disease, have shown positive results.[6]

Further studies consisting of both clinical evidence and molecular genetic evidence are encouraged. By combining both strategies, optimal results can be obtained. Though contradicting results exist to date, focusing studies on chromosomes 3 for AD and 6 and 16 for psoriatic disease, in particular HLA-C, may result in more significant results. Manipulation of chromosomal inheritance using the Mosaic Analysis with Double Markers (MADM) method, which has been used to study imprinting effects in the brain and liver, in psoriatic mouse models is a potential path to explore.[31] In addition, Burden et al. was the first to present proof of genetic anticipation in psoriasis, with an earlier age of onset if the father was affected when compared to the mother. Future studies may consider looking at whether other factors of disease, such as the type, severity, and responsiveness to treatment of psoriasis, also have a parental bias.

Psoriasis and AD are complex, multifactorial diseases which have an inheritance pattern yet to be determined. The studies reviewed here show some evidence that paternal and maternal transmission of both AD and psoriatic diseases may be biased . Based on these reports, if a father has psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, the future child may be more likely to develop the disease than if the mother was affected. However, for AD, if the mother has a history of atopy, the future child may be more likely to be affected than if the father was affected. Further research is needed to substantiate these initial findings, which if shown to be correct could be incorporated into genetic counseling of patients.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01AR065174 and K08AR057763 to WL).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pignatta D, Gehring M. Imprinting meets genomics: new insights and new challenges. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2012;15(5):530–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei Y, et al. MetaImprint: an information repository of mammalian imprinted genes. Development. 2014;141(12):2516–23. doi: 10.1242/dev.105320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Millington GW. Epigenetics and dermatological disease. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9(12):1835–50. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.12.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiota K, et al. Epigenetic marks by DNA methylation specific to stem, germ and somatic cells in mice. Genes Cells. 2002;7(9):961–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Millington GW. Genomic imprinting and dermatological disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31(5):681–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chao MJ, et al. Parent-of-origin effects at the major histocompatibility complex in multiple sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(18):3679–89. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace C, et al. The imprinted DLK1-MEG3 gene region on chromosome 14q32.2 alters susceptibility to type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2010;42(1):68–71. doi: 10.1038/ng.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberson ED, et al. A subset of methylated CpG sites differentiate psoriatic from normal skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(3 Pt 1):583–92. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folsgaard NV, et al. Neonatal cytokine profile in the airway mucosal lining fluid is skewed by maternal atopy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(3):275–80. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1471OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson CC, Ownby DR, Peterson EL. Parental history of atopic disease and concentration of cord blood IgE. Clin Exp Allergy. 1996;26(6):624–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruiz RG, Kemeny DM, Price JF. Higher risk of infantile atopic dermatitis from maternal atopy than from paternal atopy. Clin Exp Allergy. 1992;22(8):762–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1992.tb02816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shirakawa T, et al. Linkage between severe atopy and chromosome 11q13 in Japanese families. Clin Genet. 1994;46(3):228–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1994.tb04231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cookson WO, et al. Maternal inheritance of atopic IgE responsiveness on chromosome 11q. Lancet. 1992;340(8816):381–4. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91468-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauch K, et al. Linkage analysis of asthma and atopy including models with genomic imprinting. Genet Epidemiol. 2001;21(Suppl 1):S204–9. doi: 10.1002/gepi.2001.21.s1.s204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demenais F, Chaudru V, Martinez M. Detection of parent-of-origin effects for atopy by model-free and model-based linkage analyses. Genet Epidemiol. 2001;21(Suppl 1):S186–91. doi: 10.1002/gepi.2001.21.s1.s186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferreira MA, et al. Characterization of the methylation patterns of MS4A2 in atopic cases and controls. Allergy. 2010;65(3):333–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox HE, et al. Association of atopic dermatitis to the beta subunit of the high affinity immunoglobulin E receptor. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138(1):182–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yotsumoto S, Kanzaki T, Ko MS. The beta subunit of the high-affinity IgE receptor, a candidate for atopic dermatitis, is not imprinted. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142(2):370–1. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee YA, et al. A major susceptibility locus for atopic dermatitis maps to chromosome 3q21. Nat Genet. 2000;26(4):470–3. doi: 10.1038/82625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traupe H, et al. Psoriasis vulgaris, fetal growth, and genomic imprinting. Am J Med Genet. 1992;42(5):649–54. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burden AD, et al. Genetics of psoriasis: paternal inheritance and a locus on chromosome 6p. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110(6):958–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahman P, et al. Excessive paternal transmission in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(6):1228–31. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199906)42:6<1228::AID-ANR20>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karason A, et al. A susceptibility gene for psoriatic arthritis maps to chromosome 16q: evidence for imprinting. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(1):125–31. doi: 10.1086/345646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giardina E, et al. Psoriatic arthritis and CARD15 gene polymorphisms: no evidence for association in the Italian population. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122(5):1106–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyagaki T, Sugaya M. Recent advances in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: genetic background, barrier function, and therapeutic targets. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;78(2):89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee YL, et al. Association of STAT6 genetic variants with childhood atopic dermatitis in Taiwanese population. J Dermatol Sci. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li L, et al. The allele T of rs10852936 confers risk for early-onset psoriasis. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;77(2):129–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamari M, et al. An association study of 36 psoriasis susceptibility loci for psoriasis vulgaris and atopic dermatitis in a Japanese population. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;76(2):156–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, et al. Mutation analysis of the IL36RN gene in Chinese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis with/without psoriasis vulgaris. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;76(2):132–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rahman P, et al. High resolution mapping in the major histocompatibility complex region identifies multiple independent novel loci for psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(4):690–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.133561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hippenmeyer S, Johnson RL, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with double markers reveals cell-type-specific paternal growth dominance. Cell Rep. 2013;3(3):960–7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]