Abstract

Sex variation has been persistently investigated in studies concerning acute myeloid leukemia (AML) survival outcomes but has not been fully explored among pediatric and young adult AML patients. We detected sex difference in the survival of AML patients diagnosed at ages 0-24 years and explored distinct effects of sex across subgroups of age at diagnosis, race-ethnicity and AML subtypes utilizing the United States Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) population based dataset of 4,865 patients diagnosed with AML between 1973 and 2012. Kaplan-Meier survival function, propensity scores and stratified Cox proportional hazards regression were used for data analyses. After controlling for other prognostic factors, females showed a significant survival advantage over their male counterparts, adjusted hazard ratio (aHR, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.09, 1.00–1.18). Compared to females, male patients had substantially increased risk of mortality in the following subgroups of: ages 20-24 years at diagnosis (aHR1.30), Caucasian (1.14), acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) (1.35), acute erythroid leukemia (AEL) (1.39), AML with inv(16)(p13.1q22) (2.57), AML with minimum differentiation (1.47); and had substantially decreased aHR in AML t(9;11)(p22;q23) (0.57) and AML with maturation (0.82). Overall, females demonstrated increased survival over males and this disparity was considerably large in patients ages 20-24 years at diagnosis, Caucasians, and in AML subtypes of AML inv(16), APL and AEL. In contrast, males with AML t(9;11)(p22;q23), AML with maturation and age at diagnosis of 10-14 years showed survival benefit. Further investigations are needed to detect the biological processes influencing the mechanisms of these interactions.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a heterogeneous disease with marked variation in both response to therapy and survival [1,2]. AML is more frequent in adults than in children [3,4]. Prognostic factors identified to date include morphology [5,6], immunophenotype [7,8], molecular and cytogenetic markers [9-12], as well as host factors such as age at diagnosis [13,14], race-ethnicity [15-17], sex [18,19] and socio-economic status [20,21]. AML survival in all age groups, including childhood and young adult patients, has dramatically improved in recent decades [22-26]. Contributing factors to the improved survival include advancements in the diagnosis of AML, as well as refinements in the risk-stratified treatment mainly based on age and AML subtype categorized by morphology and cytogenetics [5,27]. Although not often used for therapeutic risk classification, race-ethnicity is another significant prognostic factor of AML outcome in pediatric and young adult patients in the US; African American and Hispanic patients have a significantly worse outcome than Caucasian counterparts [17]. Besides these factors, sex has been the most frequently investigated patient characteristic of pediatric and young adult AML survival in the literature. However, the exploration of the effect of sex and its interaction with other prognostic factors has been limited. Potential reasons could include the lack of adequate focus or the use of a data set not sufficiently large for optimal characterization. Synthesis of current findings of most studies leads to the speculation that females have survival advantage over their male counterparts, and survival patterns differ between the sexes in different subgroups of age at diagnosis, race-ethnicity and AML subtypes [5-31]. Published reports are limited to explain the reason behind this association and inadequate to characterize the extent of the survival variability by sex in pediatric and young adult AML patients as well as in different subgroups of these patients. Further research is warranted to quantify the effect of sex in different prognostic groups of pediatric and young adult AML patients using a large dataset.

In this study, we have characterized the extent of the association of sex and the survival patterns of AML patients diagnosed between ages 0-24 years in the US, using the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Result (SEER) dataset between 1973 and 2012. We have quantified this association for the overall population as well as for subgroups across age at diagnosis, race-ethnicities and cytogenetic- and morphologic-based AML subtypes. The SEER program of the National Cancer Institute is the most comprehensive and reliable source of population-based information in the US on cancer incidence and survival and provides a large dataset that is ideal for an epidemiological investigation like ours [32,33]. Patients in the SEER dataset are diagnosed over many years and are at varying risk of mortality at the time of diagnosis as survival improved over time. We stratified the analysis by five-year intervals of year of diagnosis to account for the time-varying survival pattern.

Methods

Data Source

This study utilized case listings of pediatric (0-19 years) and young adult (20-24 years, by UN definition [34]) AML patients from 17 SEER registries between 1973 and 2012. The SEER registries locate in geographically diverse regions and collect demographic, clinical treatment and outcome data on cancer patients representing approximately 28% of the US population. The SEER covered population is comparable to the general US population with regards to sex, race-ethnicity, and measures of poverty and education [35]. Detailed descriptions of the SEER data are available in the SEER Program Coding and Staging Manual [36]. We identified 4,879 AML patients aged 0 to 24 years at the time of diagnosis. Excluding 14 children with missing follow-up time, a total of 4,865 subjects were used for the analysis.

Study variables were age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity, number of primaries, receipt of radiation, year of diagnosis, AML subtypes, percentage of families in counties with income below poverty level, geographic region, follow-up time and survival status. The detail descriptions of these variables and categorizations are consistent with our previous publication [37]. Age at diagnosis was recorded in the SEER data as <1, 1-4, 5-9, 10-14, 15-19 and 20-24 years; we used the same categories for this variable. SEER variables “Race recode” and “Origin recode NHIA” were used to form the following mutually exclusive race-ethnicity groups: non-Hispanic Caucasian (Caucasian), non-Hispanic African American (AA), Hispanics and others. Number of primaries was dichotomized into “single/multiple” as only 5.7% of patients in our sample had more than one primary. Receipt of radiation was categorized as “yes/no/unknown”. Year of AML diagnosis was grouped into 5-year intervals: 1973-1977, 1978-1982, 1983-1987, 1988-1992, 1993-1997, 1998-2002, 2003-2007, 2008-2012. Percentage of families with income below poverty was categorized into quartiles, with patients in Quartile 1 and 4 from counties with the lowest and highest 25% of family income below poverty, respectively. SEER registries are located in 5 contract health service delivery areas (CHSDA) in the US: East, Pacific Coast, Northern Plains, Southwest and Alaska. Fourteen patients were from Alaska, and the hazard rate in this region was comparable to that in the Pacific Coast, so we collapsed data from these two regions.

In the SEER data, AML subtypes were classified by the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third Edition (ICD-O-3) / WHO 2008 definitions [27,36]. The AML subtypes as they appeared in the SEER data, along with italicized abbreviations used in this study, are as follows—9840/3: Acute erythroid leukemia (M6 type), AEL; 9861/3: Acute myeloid leukemia, AML-NOS; 9866/3: Acute promyelocytic leukemia (AML with t(15;17)(q22;q12)) PML/RARA, APL; 9867/3: Acute myelomonocytic leukemia, AMML; 9897/3: Acute myeloid leukemia with t(9;11)(p22;q23);MLLT3-MLL, AML t(9); 9910/3: Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia, AMKL; 9871/3: AML with inv(16)(p13.1q22) or t(16;16)(p13.1;q22),CBFB-MYH11, AML inv(16); 9872/3: Acute myeloid leukemia with minimal differentiation, AML min diff; 9873/3: Acute myeloid leukemia without maturation, AML w/o mat; 9874/3: Acute myeloid leukemia with maturation, AML w/ mat; 9895/3: AML with myelodysplasia-related changes (multilineage dysplasia), AML-MRC; 9896/3: Acute myeloid leukemia, t(8;21)(q22;q22) RUNX1-RUNX1T1, AML t(8); 9920/3: Therapy-related (acute) myeloid neoplasm, t-AML. The ICD codes 9840/3, 9861/3, 9866/3, 9867/3, 9897/3 and 9910/3 were reportable since 1978, while the rest of the above were reportable since 2001. In addition, 9865/3: Acute myeloid leukemia with t(6;9)(p23;q34) DEK-NUP214, AML t(6); 9869/3: Acute myeloid leukemia with inv(3)(q21;q26.2) or t(3;3)(q21;q26.2), AML inv(3); RPN1-EVI1; 9898/3: Myeloid leukemia associated with Down Syndrome, AML w/ DS; and 9865/3: Acute myeloid leukemia with t(1;22)(p13;q13), AML t(1) became reportable since 2010. The follow-up time was documented as the duration from the time of diagnosis to death or the last day of the available survival information in the SEER registry. The SEER variable “vital status recode” was used to determine overall mortality.

Statistical Analysis

The distribution of pediatric and young adult AML patients and their overall mortality were summarized by sex and other study variables. Kaplan-Meier survival curve was used to compare the crude probability of survival over time since diagnosis between males and females. A univariable Cox proportional hazard model was used to determine the association of sex and other study variables with the risk of mortality; the model was stratified by the year of diagnosis to account for the time-varying survival pattern. A stratified multivariable Cox proportional hazard model was used to determine the association between sex and mortality in pediatric and young adult AML patients after adjustment for significant prognostic factors identified in the univariable model. In addition to sex, age at diagnosis, race-ethnicity, number of primaries, radiation, AML subtype, percent families with income below poverty in county and geographic region were used in the model. The rationale and the method of the stratified Cox proportional hazards model are previously described [37]. To assess the effect of sex in different subgroups of age at diagnosis, race-ethnicities and AML subtypes of pediatric and young adult AML patients, we performed Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and propensity scores adjusted Cox-proportional hazards model on the dataset of each subgroup [38]. Out of the three above factors, two were used as covariates to estimate propensity scores for the subgroup analysis involving the other factor. For example, race-ethnicity and AML subtypes were used as covariates to estimate propensity scores for the subgroup analysis involving age at diagnosis. Because of the small number of patients in some subgroups, propensity score of covariates was used for the adjustment instead of the covariates themselves. For Kaplan-Meier plots, data were merged for subgroups with homogeneous distributions of the crude probability of survivals. All analyses were two-tailed with the level of significance of 0.05. The statistical software SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for data analyses.

Results

Among 4,865 children and young adult AML patients, there were 2,520 (52%) males and 2,345 (48%) females. Table 1 characterized the study variables by sex. No substantial differences were observed in the distributions of male and female patients over age at diagnosis, race-ethnicity, number of primaries, receipt of radiation, geographic region and county poverty level. The distribution of sexes across AML subtypes were substantially different (p < 0.001). Prevalence of AML-NOS, AMML, AML min diff, AML w/o mat and AML-MRC was higher in males, while that of APL, AML inv(16) and AMKL was higher in females. The distribution of overall mortality was significantly higher in males (52%) than in females (48%), p = 0.006. Five- and ten-year proportion of survivals was higher in females (51% and 48%) than males (46% and 43%).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Pediatric and Young Adult AML Patients in the United States SEER Data, 1973-2012.

| Variables | Female (N = 2,345) n (%) |

Male (N = 2,520) n (%) |

χ 2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis, years | ||||

| <1 | 157 (49) | 166 (51) | 1.15 | 0.95 |

| 1-4 | 411 (48) | 446 (54) | ||

| 5-9 | 262 (48) | 285 (52) | ||

| 10-14 | 398 (47) | 450 (53) | ||

| 15-19 | 515 (48) | 553 (52) | ||

| 20-24 | 602 (49) | 620 (51) | ||

| Race | 3.41 | 0.33 | ||

| Caucasian | 1231 (48) | 1329 (52) | ||

| AA | 290 (52) | 273 (48) | ||

| Hispanics | 567 (47) | 644 (53) | ||

| Other | 257 (48) | 274 (52) | ||

| Number of Primaries | 0.004 | 0.95 | ||

| 1 | 2213 (48) | 2376 (52) | ||

| ≥ 2 | 132 (48) | 144 (52) | ||

| Radiation | 0.01 | 0.92 | ||

| No/Refused | 2078 (48) | 2233 (52) | ||

| Yes | 258 (49) | 273 (51) | ||

| CHSDA Regions | 1.39 | 0.71 | ||

| East | 663 (49) | 697 (51) | ||

| Pacific Coast | 1146 (48) | 1252 (52) | ||

| Northern Plains | 338 (50) | 342 (50) | ||

| Southwest | 198 (47) | 227 (53) | ||

| Percent Families Below Poverty | 7.49 | 0.06 | ||

| Q1 | 635(47) | 725 (53) | ||

| Q2 | 560 (50) | 565(50) | ||

| Q3 | 685 (46) | 789 (54) | ||

| Q4 | 465 (51) | 442 (49) | ||

| AML Subtype | 41.79 | <0.001 | ||

| APL | 343 (55) | 285 (45) | ||

| AML-NOS | 1219 (47) | 1362 (53) | ||

| AEL | 35 (50) | 35 (50) | ||

| AML t(6) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | ||

| AMML | 188 (45) | 234 (55) | ||

| AML inv(3) | 1 (100) | 0 | ||

| AML inv(16) | 50 (63) | 29 (37) | ||

| AML min diff | 49 (38) | 80 (62) | ||

| AML w/o mat | 73 (41) | 105 (59) | ||

| AML w/ mat | 121 (51) | 117 (49) | ||

| AML-MRC | 14 (32) | 30 (62) | ||

| AML t(8) | 53 (49) | 55 (51) | ||

| AML t(9) | 20 (39) | 31 (61) | ||

| AML w/ DS | 13 (54) | 11 (46) | ||

| AMKL | 132 (54) | 113 (46) | ||

| AMKL t(1) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | ||

| t-AML | 32 (51) | 31 (49) | ||

| Year of Diagnosis | 3.00 | 0.08* | ||

| 1973-1977 | 141 (50) | 141 (50) | ||

| 1978-1982 | 134 (49) | 141 (51) | ||

| 1983-1987 | 117 (48) | 129 (52) | ||

| 1988-1992 | 152 (50) | 155 (50) | ||

| 1993-1997 | 231 (46) | 272 (54) | ||

| 1988-2992 | 407 (46) | 483 (54) | ||

| 2003-2007 | 544 (48) | 580 (52) | ||

| 2008-2012 | 619 (50) | 619 (50) | ||

| Survival time (months) | 0.32^ | |||

| Median (95% CI‡) | 92 (86-98) | 93 (88-98) | ||

| Mean (SE) | 63.9 (1.7) | 57.3 (1.6) | ||

| Five-year interval survival (months) | ||||

| 0-60 | 0.51 (0.01) | 0.46 (0.01) | ||

| 61-120 | 0.48 (0.01) | 0.43 (0.01) | ||

| Overall Mortality | 7.44 | 0.006 | ||

| Alive | 1228 (52) | 1220 (48) | ||

| Dead | 1127 (48) | 1304 (52) |

p-values are from χ2 test for trend.

p-value is from the log-rank test.

CI: Confidence interval

Table 2 presented the distribution of mortality by sex and study variables, as well as hazard ratios (HR) associated with study variables, estimated using stratified Cox proportional hazards model. Males demonstrated a significantly higher hazard risk of death compared to female counterparts (HR, 95% CI: 1.12, 1.03– 1.21). In terms of age at diagnosis, patients diagnosed during ages 5-9 and 20-24 years exhibited the lowest (0.84, 0.70– 1.02) and the highest (1.13, 0.94– 1.35) risk of mortality compared to those diagnosed during infancy. Hazard risk of mortality increased monotonically in children diagnosed up to 9 years of age and decreased monotonically thereafter. Compared to Caucasians, AA patients had about 30% increased risk of mortality, 1.30, 1.15– 1.47). The hazard risk of mortality was significantly different across AML subtypes. AML min diff, t-AML, AEL, AMML, AML-NOS, AML t(9), AML-MRC, AML w/o mat, AML w/mat and AMKL were subtypes with leading hazard risks of mortality; while AML inv(16), APL, and AML t(8) were relatively associated with favorable survival outcome. In addition, patients with multiple primaries, counties with higher percentage of families below poverty and the Southwest CHSDA region were associated with higher risk of mortality

Table 2. Distribution of Pediatric and Young Adult AML Mortality by Sex and Hazard Risk Associated with Study Variables, SEER 1973-2012.

| Variables | Female (N = 2345) Mortality, n (%) |

Male (N = 2520) Mortality, n (%) |

Hazard Ratio (HR) |

95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Female | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Male | - | - | 1.12 | 1.03, 1.21 | 0.006 |

| Age at Diagnosis, years | |||||

| <1 | 74 (47) | 74 (44) | 1 | - | - |

| 1-4 | 176 (43) | 189 (42) | 0.84 | 0.70, 1.02 | 0.08 |

| 5-9 | 118 (45) | 127 (45) | 0.77 | 0.63, 0.95 | 0.01 |

| 10-14 | 201 (51) | 227 (50) | 0.97 | 0.81, 1.17 | 0.76 |

| 15-19 | 255 (50) | 312 (57) | 1.09 | 0.91, 1.31 | 0.33 |

| 20-24 | 293 (49) | 370 (60) | 1.13 | 0.94, 1.35 | 0.18 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Caucasian | 586 (48) | 703 (53) | 1 | - | - |

| AA | 165 (57) | 161 (59) | 1.3 | 1.15, 1.47 | <.001 |

| Hispanics | 249 (44) | 293 (46) | 1.12 | 1.01, 1.24 | 0.03 |

| Other | 117 (46) | 143 (52) | 1.06 | 0.92, 1.21 | 0.43 |

| Number of Primaries | |||||

| 1 | 1046 (47) | 1216 (51) | 1 | - | - |

| ≥2 | 71 (54) | 84 (58) | 1.26 | 1.07 , 1.49 | 0.005 |

| Radiation | |||||

| No/Refused | 980 (47) | 1139 (51) | 1 | - | - |

| Yes | 135 (52) | 156 (57) | 1 | 0.88, 1.13 | 0.97 |

| AML Subtype | |||||

| APL | 82 (24) | 96 (34) | 1 | - | - |

| AML-NOS | 710 (58) | 798 (59) | 1.93 | 1.65, 2.27 | <.001 |

| AEL | 18 (51) | 25 (71) | 2.21 | 1.58, 3.09 | <.001 |

| AML t(6) | - | 1 (100) | 4.25 | 0.59, 30.43 | 0.15 |

| AMML | 87 (46) | 118 (50) | 1.94 | 1.59, 2.37 | <.001 |

| AML inv (16) | 6 (12) | 6 (20.7) | 0.63 | 0.35, 1.13 | 0.12 |

| AML min diff | 26 (53) | 52 (65) | 2.58 | 1.98, 3.38 | <.001 |

| AML w/o mat | 33 (45) | 51 (48) | 1.98 | 1.52, 2.57 | <.001 |

| AML w/ mat | 54 (45) | 46 (39) | 1.66 | 1.3, 2.13 | <.001 |

| AML-MRC | 5 (36) | 13 (43) | 1.91 | 1.18, 3.11 | 0.009 |

| AML t(8) | 16 (30) | 17 (31) | 1.35 | 0.93, 1.96 | 0.11 |

| AML t(9) | 9 (45) | 9 (29) | 1.88 | 1.16, 3.06 | 0.01 |

| AMKL | 53 (40) | 51 (45) | 1.68 | 1.32, 2.14 | <.001 |

| t-AML | 17 (53) | 16 (52) | 3.99 | 2.73, 5.83 | <.001 |

| CHSDA Regions | |||||

| East | 284 (43) | 324 (47) | 1 | - | - |

| Pacific Coast | 520 (45) | 622 (50) | 1.07 | 0.97, 1.18 | 0.17 |

| Northern Plains | 203 (60) | 220 (64) | 1.04 | 0.91, 1.18 | 0.60 |

| Southwest | 110 (56) | 134 (59) | 1.16 | 0.99, 1.34 | 0.06 |

| Percent Families Below Poverty | |||||

| Q1 | 298 (47) | 401(55) | 1 | - | - |

| Q2 | 270 (48) | 298(53) | 0.94 | 0.84, 1.05 | 0.24 |

| Q3 | 311(45) | 360 (46) | 1.05 | 0.94, 1.17 | 0.35 |

| Q4 | 238 (51) | 241 (55) | 1.21 | 1.08, 1.37 | 0.001 |

| Year of Diagnosis | |||||

| 1973-1977 | 123 (87.2) | 123 (87.2) | |||

| 1978-1982 | 112 (83.6) | 119 (84.4) | |||

| 1983-1987 | 73 (62.4) | 108 (83.7) | |||

| 1988-1992 | 90 (59.2) | 102 (65.8) | |||

| 1993-1997 | 134 (58) | 165 (60.7) | |||

| 1998-2002 | 206 (50.6) | 250 (51.8) | |||

| 2003-2007 | 220 (40.4) | 252 (43.5) | |||

| 2008-2012 | 159 (25.7) | 181 (29.2) |

Table 3 demonstrated the association of sex with mortality after adjusting for other risk factors. The adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) of mortality associated with sex and other prognostic factors were estimated using a multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model stratified by year of diagnosis intervals. The significant difference between the sexes in the unadjusted model persisted after adjustment for the effect of other risk and protective factors on the relationship between sex and overall survival (1.09, 1– 1.18). Adjustment using the propensity scores estimated using covariates age at diagnosis, race-ethnicity and AML subtypes yielded the similar results (1.09, 1.01-1.18), p = 0.03. In addition to sex, age at diagnosis, race-ethnicity and AML subtypes, the hazard risk of mortality varied substantially between geographic regions and percent families below county poverty level.

Table 3. Adjusted Hazard Risk of Mortality (aHR) Estimated by Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards Model, Stratified by Year of Diagnosis.

| Variables | aHR† (95% CI*) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | - | - |

| Male | 1.09 (1.00, 1.18) | 0.04 |

| Age at Diagnosis, years | ||

| <1 | - | - |

| 1-4 | 0.87 (0.72, 1.06) | 0.16 |

| 5-9 | 0.82 (0.66, 1.01) | 0.06 |

| 10-14 | 1.06 (0.87, 1.28) | 0.59 |

| 15-19 | 1.19 (0.99, 1.44) | 0.07 |

| 20-24 | 1.27 (1.05, 1.52) | 0.01 |

| Race-Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | - | - |

| AA | 1.29 (1.14, 1.47) | <.001 |

| Hispanics | 1.09 (0.97, 1.22) | 0.14 |

| Other | 1.01 (0.88, 1.17) | 0.88 |

| Number of Primaries | ||

| 1 | - | - |

| ≥ 2 | 1.10 (0.92, 1.32) | 0.29 |

| Radiation | ||

| No | - | - |

| Yes | 0.93 (0.82, 1.05) | 0.23 |

| AML Subtype | ||

| APL | - | - |

| AML-NOS | 2.05 (1.75, 2.42) | <.001 |

| AEL | 2.37 (1.69, 3.32) | <.001 |

| AMML | 1.99 (1.62, 2.43) | <.001 |

| AML inv(16) | 0.67 (0.37, 1.2) | 0.18 |

| AML min diff | 2.74 (2.09, 3.59) | <.001 |

| AML w/o mat | 2.04 (1.57, 2.66) | <.001 |

| AML w/ mat | 1.81 (1.41, 2.32) | <.001 |

| AML-MRC | 2.08 (1.27, 3.39) | 0.004 |

| AML t(8) | 1.41 (0.97, 2.05) | 0.07 |

| AML t(9) | 2.09 (1.28, 3.41) | 0.003 |

| AMKL | 2.04 (1.58, 2.63) | <.001 |

| t-AML | 4.03 (2.67, 6.08) | <.001 |

| Geographic Region | ||

| East | - | - |

| Pacific Coast | 1.03 (0.9, 1.17) | 0.71 |

| Northern Plains | 1.14 (1.02, 1.27) | 0.02 |

| Southwest | 1.2 (1.03, 1.4) | 0.02 |

| Percent Families Below Poverty | ||

| Q1 | - | - |

| Q2 | 0.94 (0.84, 1.05) | 0.25 |

| Q3 | 1.03 (0.92, 1.16) | 0.60 |

| Q4 | 1.19 (1.04, 1.34) | 0.008 |

aHR: Adjusted Hazard Ratio.

CI: Confidence Interval.

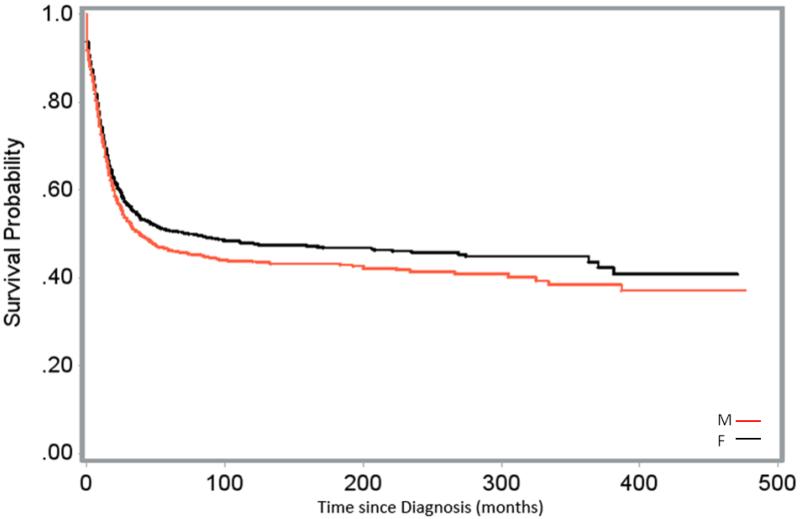

Figures 1-3 demonstrated the effect of sex and its interaction with the established biological prognostic factors of AML on patient survival. Figure 1 displayed the comparisons of the distribution of crude survival over time since diagnosis between male and female pediatric and young adult AML patients. The probability of survival was higher in females over the months after diagnosis. The survival distribution between the two sexes by age at diagnosis and race-ethnicity were shown in Figure 2a and 2b, respectively. Males showed a higher probability of survival than females in patients diagnosed with AML during infancy; survival was similar between the sexes in patients diagnosed at ages 1-14 years; female patients diagnosed at 15-24 years of age showed a substantially higher probability of survival than their male counterparts. Caucasian and Hispanic female patients showed a post-diagnosis higher probability of survival compared to their male counterparts; there was no difference in the post-diagnosis survival probability between female and male AA patients.

Figure 1.

Survival of Male (M) and Female (F) Pediatric and Young Adult AML Patients, SEER Data, 1973-2012.

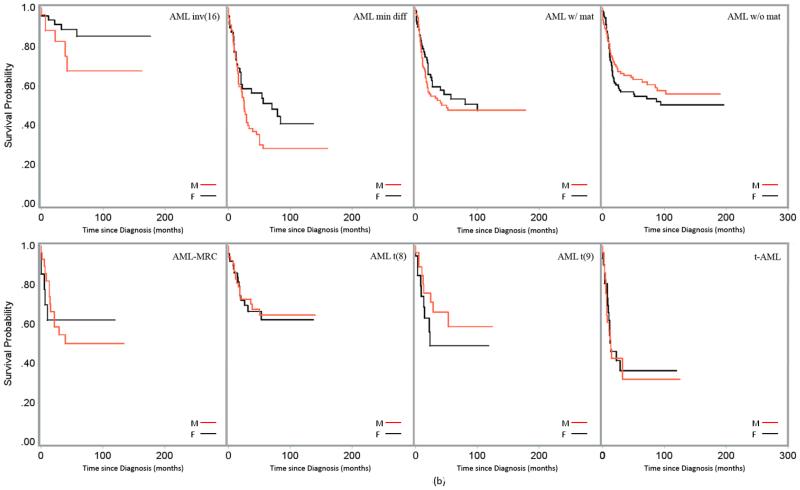

Figure 3.

(a). Survival of Male (M) and Female (F) Pediatric and Young Adult AML Patients Across Subgroups of Age at Diagnosis, SEER Data, 1973-2012. Survival (unadjusted) by AML subtype was displayed in Figures 3(a) and 3(b).

(b) Survival of Male (M) and Female (F) Pediatric and Young Adult AML Patients Across Subgroups of Age at Diagnosis, SEER Data, 1973-2012. Survival (unadjusted) by AML subtype was displayed in Figures 3(a) and 3(b).

Figure 2.

(a). Survival of Male (M) and Female (F) Pediatric and Young Adult AML Patients Across Subgroups of Age at Diagnosis, SEER Data, 1973-2012.

(b). Survival of Male (M) and Female (F) Pediatric and Young Adult AML Patients Across Subgroups of Race-ethnicity, SEER Data, 1973-2012.

Figures 3a and 3b demonstrated the distribution of post-diagnosis crude probability of survival of male and female AML patients of ages at diagnosis 0-24 years by AML subtypes. Female patients showed a substantially superior probability of survival among patients with subtypes APL, AEL, AMML, AMKL, AML inv(16), AML min diff, AML w/o mat and AML-MRC; while male patients in subtypes AML with mat and AML t(9) exhibited a superior probability of surviving. No substantial difference between the sexes was observed in patients with AML-NOS.

Table 4 presented the propensity score adjusted hazard risk of mortality of male patients compared to female counterparts across subgroups of age at diagnosis, race-ethnicity and AML subtypes. On average, the risk of mortality in males were 30% higher than that in female patients diagnosed in their early 20s; in other groups of age at diagnosis, the risk between males and females were comparable with males having slightly elevated risk except the ages 10-14 at diagnosis. In Caucasians (1.14, 1.02– 1.27) and patients of other races/ethnicities (1.27, 0.99– 1.63), male patients’ risk of mortality was substantially higher than that of females. Female APL patients had significantly better survival probability than male counterparts (1.35, 1-1.83). Although statistically not significant, female patients in subgroups of AML inv(16) (aHR 2.57), AEL (aHR 1.39), and AML min diff (aHR 1.47), AMKL (aHR 1.21) and t-AML (aHR 1.19) showed a considerably superior survival outcome compared to their male counterparts. Males, on the other hand, demonstrated a better survival outcome if they had AML w/ mat (aHR 0.82) or AML t(9) (aHR 0.57).

Table 4. Propensity Score Adjusted Cox-proportional Hazards Model to Compare Risk of Mortality between Male and Female Pediatric and Young Adult AML Patients Across Subgroups of Age at Diagnosis, Race-Ethnicity and AML Subtypes; SEER Data, 1973-2012.

| Subgroups | *aHR (Reference = Female) | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis, years | |||

| <1 | 1.04 | 0.74, 1.45 | 0.84 |

| 1-4 | 1.08 | 0.88, 1.33 | 0.45 |

| 5-9 | 1.01 | 0.78, 1.31 | 0.92 |

| 10-14 | 0.93 | 0.77, 1.12 | 0.43 |

| 15-19 | 1.05 | 0.89, 1.25 | 0.54 |

| 20-24 | 1.30 | 1.12, 1.52 | <0.001 |

| Race-Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 1.14 | 1.02, 1.27 | 0.02 |

| AA | 0.98 | 0.79, 1.22 | 0.86 |

| Hispanics | 1.00 | 0.85, 1.19 | 0.96 |

| Other | 1.27 | 0.99, 1.63 | 0.07 |

| AML Subtype | |||

| APL | 1.35 | 1.00, 1.83 | 0.05 |

| AML-NOS | 1.06 | 0.96, 1.17 | 0.29 |

| AEL | 1.39 | 0.72, 2.67 | 0.33 |

| AMML | 1.07 | 0.81, 1.42 | 0.63 |

| AML inv(16) | 2.57 | 0.79, 8.36 | 0.12 |

| AML min diff | 1.47 | 0.91, 2.37 | 0.11 |

| AML w/o mat | 1.13 | 0.73, 1.76 | 0.58 |

| AML w/ mat | 0.82 | 0.55, 1.21 | 0.31 |

| AML-MRC | 1.10 | 0.38, 3.19 | 0.86 |

| AML t(8) | 0.90 | 0.45, 1.81 | 0.76 |

| AML t(9) | 0.57 | 0.22, 1.47 | 0.24 |

| AMKL | 1.21 | 0.82, 1.79 | 0.33 |

| t-AML | 1.19 | 0.60, 2.38 | 0.62 |

aHR: Propensity Score Adjusted Hazard Ratio

Discussion

The risk of mortality in pediatric and young adult AML patients substantially varies by distinct cytogenetic, molecular, clinical features and biologic characteristics [5-31]. As previously mentioned, increased understanding of the disease etiology and therapeutic responses contributed to the dramatic improvement in patient survival in the past two to three decades. Age at diagnosis, race-ethnicity, cytogenetic and molecular features are the major factors in the prognosis of pediatric and young adult AML survival. We confirmed the prognostic values of these factors in patients of our study. We also confirmed survival variation associated with socioeconomic status and geographic region, as recently reported by Petridou et al. [20]. The principal findings of our study are: i). significant effect of sex on the survival of pediatric and young adult AML patients in the US; and ii). variation of survival between the sexes among subgroups by age at diagnosis, race-ethnicity and AML subtype.

While studies reported mixed results [19,28,39-41], females in our study showed a substantially increased survival benefit than their male counterparts in patients diagnosed between 0-24 years of age. We detected a differential effect of sex over the age groups at diagnosis. Female patients diagnosed at ages <1, 1-4 and 15-19 years demonstrated modest survival advantage, and those diagnosed at age 20-24 years exhibited the largest survival benefit over male counterparts. This sex effect reversed in patients diagnosed between ages 10-14 years. Male patients diagnosed between ages 10-14 years exhibited survival benefit over female counterparts. Compared to males, the relative hazard risk of females increased in patients diagnosed at age groups of 5-9 and 10-14 years with its peak at age of diagnosis of 10-14 years. It appears that in general, females had survival benefit over males, but this trend was attenuated in patients diagnosed at 5-9 and 10-14 years, which might have been associated with the earlier onset of puberty in females. Puberty usually begins between 8-15 years of age and ends between 12-17 in females; and, in males, it occurs later, beginning between 10-14 and ending between 14-18 years [42]. We reported the survival difference by sex and age at diagnosis for the first time in adolescent and young adult AML patients. The variation of the sex effect at the onset of puberty or at the sexual maturation in our study was consistent with the observation of Shahabi et al. in which they detected minimal sex effect at birth, but at puberty, with acquisition of sexual maturity, sex differences started to appear and ultimately peaked during young adulthood in a number of non-sex specific cancer survival [43]. Interaction of sex hormone and biological changes during growth in this developmental period might have contributed to the observed survival difference.

We also detected significant variation in survival between males and females across race-ethnicities. In Caucasians, risk of mortality increased by14% among males, whereas the risk of mortality between males and females was almost equivalent in AA and Hispanic patients (aHR 0.98 and 1, respectively). The risk of mortality of males diagnosed between 0-24 years of age in the other race/ethnicity group exceeded that of females in the same group by 27%. This group comprises of patients with diverse race-ethnicities. To our knowledge, no studies reported the interaction of sex and race-ethnicity on the survival of pediatric and young adult AML.

In this study, we detected survival variation by sex across the AML subtypes. In male patients, there was a substantial increased risk of death associated with the APL and AML-inv(16) subtypes, (aHR 1.35 and 2.57, respectively); moderately increased risk associated with AML min diff and AEL (aHR 1.47 and 1.39, respectively); and slightly increased risk associated with the subtypes AMKL, t-AML, AML w/o mat, AML-MRC and AML-NOS. The survival outlook was more optimal for males having AML t(9), AML with mat or AML t(8). Report on the sex-specific AML subtype survival has been scant, especially in the pediatric and young adult population. Chang et. al. reported that in children and adolescent, female patients with AML t(8), inv(16), or a normal karyotype had better prognosis than males with the same genetic profiles [28]. Findings from the adult literature showed that female AML-MRC patients conferred survival advantage [44,45], outcome was superior in female APL patients [46]. Molecular, genetic and other biological disease features might have contributed to the survival differences between the sexes over AML subtypes [47,48].

Like most epidemiological studies, the current study was not without limitations. First, SEER data were routinely collected in the course of long follow-up time and observational in nature. We applied precaution during the data analysis and used propensity score adjustment and stratified analysis to reduce the bias in estimates due to unmeasured confounders of observational studies. For example, survival improved dramatically over time, causing the baseline hazard to differ during the study period of 1973-2012. Analyses stratified by five-year intervals of diagnosis eliminated this problem. There was limited information on treatment in the SEER data [49-51]. Also, event-free survival, an important oncologic outcome, was missing in the SEER data. However, we utilized the strength of observational studies and used a very large dataset.

In conclusion, our study detected differential survival patterns between male and female pediatric and young adult AML patients. Overall, females demonstrated a considerable survival benefit, with major differences in patient subgroups of ages 20-24 years at diagnosis; Caucasian by race-ethnicity; APL, AEL, AML inv(16), and AML min diff by AML subtype. In contrary to the overall trend, males in subgroups of 10-14 years of age at diagnosis; AML t(9) and AML w/mat by subtype had better outcome than their female counterparts. Interactions of age, race-ethnicity and AML disease types and other unknown biological factors influencing treatment response might have given rise to these associations. Future research could focus on better understanding of interactions of these processes and elucidating their mechanisms.

Highlights.

Overall,female pediatric and young adult AML patients had better survival than males.

Patients diagnosed at 20-24 years and Caucasians showed largest survival difference.

AML subtypes APL,AML min diff,AML inv(16),AEL showed the largest survival disparity.

Males had better survival in subgroups AML t(9),AML w mat,diagnosis age 10-14 years.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their special appreciation to the reviewers for their valuable comments and critique. This study was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) COBRE Grant 8P20GM103464-9 (PI: Shaffer) and an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH under Grant no. U54-GM104941 (PI: Binder-Macleod).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authorship Contribution Statement

All authors contributed significantly to the preparation of this manuscript, and all approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Md Jobayer Hossain, PhD contributed to conception and design; acquisition and analysis of data; interpretations; and drafting and final approval of the submitted manuscript.

Li Xie, ScM contributed to design; data analysis and interpretations; and drafting and final approval of the submitted manuscript.

Reference

- 1.Foran JM. New prognostic markers in acute myeloid leukemia: perspective from the clinic. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010:47–55. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.47. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubnitz JE, Gibson B, Smith FO. Acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008 Feb;55(1):21–51. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2007.11.003. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deschler B, Lübbert M. Acute myeloid leukemia: epidemiology and etiology. Cancer. 2006 Nov 1;107(9):2099–107. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie Y, Davies SM, Xiang Y, Robison LL, Ross JA. Trends in leukemia incidence and survival in the United States (1973-1998) Cancer. 2003 May 1;97(9):2229–35. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, Gralnick HR, Sultan C. Proposals for the classification of the acute leukaemias. French-American-British (FAB) co-operative group. Br J Haematol. 1976 Aug;33(4):451–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1976.tb03563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, Gralnick HR, Sultan C. Proposal for the recognition of minimally differentiated acute myeloid leukaemia (AML-MO) Br J Haematol. 1991;78:325–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1991.tb04444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casasnovas RO, Slimane FK, Garand R, Faure GC, Campos L, Deneys V, Bernier M, Falkenrodt A, Lecalvez G, Maynadié M, Béné MC. Immunological classification of acute myeloblastic leukemias: relevance to patient outcome. Leukemia. 2003 Mar;17(3):515–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan DH. Phenotypic heterogeneity in acute leukemia. Clin Chim Acta. 1992;206:9–23. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(92)90004-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mistry AR, Pedersen EW, Solomon E, Grimwade D. The molecular pathogenesis of acute promyelocytic leukaemia: implications for the clinical management of the disease. Blood Rev. 2003 Jun;17(2):71–97. doi: 10.1016/s0268-960x(02)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damm F, Heuser M, Morgan M, Yun H, Grosshennig A, Göhring G, Schlegelberger B, Döhner K, Ottmann O, Lübbert M, Heit W, Kanz L, Schlimok G, Raghavachar A, Fiedler W, Kirchner H, Döhner H, Heil G, Ganser A, Krauter J. Single nucleotide polymorphism in the mutational hotspot of WT1 predicts a favorable outcome in patients with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Feb 1;28(4):578–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0342. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0342. Epub 2009 Dec 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manola KN. Cytogenetics of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Eur J Haematol. 2009 Nov;83(5):391–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01308.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01308.x. Epub 2009 Jun 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tarlock K, Meshinchi S. Pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: biology and therapeutic implications of genomic variants. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015 Feb;62(1):75–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2014.09.007. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2014.09.007. Epub 2014 Oct 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Webb DK, Harrison G, Stevens RF, Gibson BG, Hann IM, Wheatley K, MRC Childhood Leukemia Working Party Relationships between age at diagnosis, clinical features, and outcome of therapy in children treated in the Medical Research Council AML 10 and 12 trials for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2001 Sep 15;98(6):1714–20. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Razzouk BI, Estey E, Pounds S, Lensing S, Pierce S, Brandt M, Rubnitz JE, Ribeiro RC, Rytting M, Pui CH, Kantarjian H, Jeha S. Impact of age on outcome of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: a report from 2 institutions. Cancer. 2006 Jun 1;106(11):2495–502. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21892. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Appelbaum FR, Gundacker H, Head DR, Slovak ML, Willman CL, Godwin JE, Anderson JE, Petersdorf SH. Age and acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2006 May 1;107(9):3481–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3724. Epub 2006 Feb 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubnitz JE, Lensing S, Razzouk BI, Pounds S, Pui CH, Ribeiro RC. Effect of race on outcome of white and black children with acute myeloid leukemia: the St. Jude experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007 Jan;48(1):10–5. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Children’s Oncology Group. Aplenc R, Alonzo TA, Gerbing RB, Smith FO, Meshinchi S, Ross JA, Perentesis J, Woods WG, Lange BJ, Davies SM. Ethnicity and survival in childhood acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Blood. 2006 Jul 1;108(1):74–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4004. Epub 2006 Mar 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radhi M, Meshinchi S, Gamis A. Prognostic factors in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2010 Oct;5(4):200–6. doi: 10.1007/s11899-010-0060-z. doi: 10.1007/s11899-010-0060-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meshinchi S, Arceci RJ. Prognostic factors and risk-based therapy in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Oncologist. 2007 Mar;12(3):341–55. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-3-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petridou ET, Sergentanis TN, Perlepe C, Papathoma P, Tsilimidos G, Kontogeorgi E, Kourti M, Baka M, Moschovi M, Polychronopoulou S, Sidi V, Hatzipantelis E, Stiakaki E, Iliadou AN, La Vecchia C, Skalkidou A, Adami H. Socioeconomic disparities in survival from childhood leukemia in the United States and globally: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2015 Mar;26(3):589–97. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu572. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu572. Epub 2014 Dec 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel MI, Ma Y, Mitchell B, Rhoads KF. How do differences in treatment impact racial and ethnic disparities in acute myeloid leukemia? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015 Feb;24(2):344–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0963. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaspers G, Creutzig U. Pediatric AML: long term results of clinical trials from 13 study groups worldwide. Leukemia. 2005;19:2025–146. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ravindranath Y, Chang M, Steuber CP, Becton D, Dahl G, Civin C, Camitta B, Carroll A, Raimondi SC, Weinstein HJ, Pediatric Oncology Group Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) studies of acute myeloid leukemia (AML): a review of four consecutive childhood AML trials conducted between 1981 and 2000. Leukemia. 2005 Dec;19(12):2101–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith FO, Alonzo TA, Gerbing RB, Woods WG, Arceci RJ, Children’s Cancer Group Long-term results of children with acute myeloid leukemia: a report of three consecutive Phase III trials by the Children’s Cancer Group: CCG 251, CCG 213 and CCG 2891. Leukemia. 2005 Dec;19(12):2054–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woods WG, Franklin AR, Alonzo TA, Gerbing RB, Donohue KA, Othus M, Horan J, Appelbaum FR, Estey EH, Bloomfield CD, Larson RA. Outcome of adolescents and young adults with acute myeloid leukemia treated on COG trials compared to CALGB and SWOG trials. Cancer. 2013 Dec 1;119(23):4170–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28344. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28344. Epub 2013 Sep 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gramatges MM, Rabin KR. The adolescent and young adult with cancer: state of the art--acute leukemias. Curr Oncol Rep. 2013 Aug;15(4):317–24. doi: 10.1007/s11912-013-0325-5. doi: 10.1007/s11912-013-0325-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning RD, Borowitz MJ, Porwit A, Harris NL, Le Beau MM, Hellström-Lindberg E, Tefferi A, Bloomfield CD. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009 Jul 30;114(5):937–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. Epub 2009 Apr 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang M, Raimondi SC, Ravindranath Y, Carroll AJ, Camitta B, Gresik MV, Steuber CP, Weinstein H. Prognostic factors in children and adolescents with acute myeloid leukemia (excluding children with Down syndrome and acute promyelocytic leukemia): univariate and recursive partitioning analysis of patients treated on Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) Study 8821. Leukemia. 2000 Jul;14(7):1201–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Döhner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Büchner T, Burnett AK, Dombret H, Fenaux P, Grimwade D, Larson RA, Lo-Coco F, Naoe T, Niederwieser D, Ossenkoppele GJ, Sanz MA, Sierra J, Tallman MS, Löwenberg B, Bloomfield CD, European LeukemiaNet Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2010 Jan 21;115(3):453–74. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235358. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235358. Epub 2009 Oct 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linabery AM, Ross JA. Trends in childhood cancer incidence in the U.S. (1992-2004) Cancer. 2008 Jan 15;112(2):416–32. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rubnitz JE, Razzouk BI, Lensing S, Pounds S, Pui CH, Ribeiro RC. Prognostic factors and outcome of recurrence in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2007 Jan 1;109(1):157–63. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Cancer Institute [Accessed June 16, 2015];About the SEER program. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/about.

- 33.National Cancer Institute [Accessed June 16, 2015];Population characteristics. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/registries/characteristics.html.

- 34.Geiger AM, Castellino SM. Delineating the age ranges used to define adolescents and young adults. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Jun 1;29(16):e492–3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.5602. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.5602. Epub 2011 Apr 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park HS, Lloyd S, Decker RH, Wilson LD, Yu JB. Overview of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database: evolution, data variables, and quality assurance. Curr Probl Cancer. 2012 Jul-Aug;36(4):183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2012.03.007. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2012.03.007. Epub 2012 Apr 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adamo M, Dickie L, Ruhl J. SEER Program Coding and Staging Manual 2015. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: Jan, 2015. pp. 20850–9765. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hossain MJ, Xie L, Caywood EH. Prognostic factors of childhood and adolescent acute myeloid leukemia (AML) survival: Evidence from four decades of US population data. Cancer Epidemiology. 2015 Jul. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.06.009. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel MI, Ma Y, Mitchell BS, Rhoads KF. Age and genetics: how do prognostic factors at diagnosis explain disparities in acute myeloid leukemia? Am J Clin Oncol. 2015 Apr;38(2):159–64. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31828d7536. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31828d7536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burke MJ, Gossai N, Cao Q, Macmillan ML, Warlick E, Verneris MR. Similar outcomes between adolescent/young adults and children with AML following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014 Feb;49(2):174–8. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.171. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.171. Epub 2013 Nov 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canner J, Alonzo TA, Franklin J, Freyer DR, Gamis A, Gerbing RB, Lange BJ, Meshinchi S, Woods WG, Perentesis J, Horan J. Differences in outcomes of newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia for adolescent/young adult and younger patients: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2013 Dec 1;119(23):4162–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28342. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28342. Epub 2013 Sep 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee PA. Normal ages of pubertal events among American males and females. J Adolesc Health Care. 1980 Sep;1(1):26–9. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0070(80)80005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shahabi S, He S, Kopf M, et al. Free testosterone drives cancer aggressiveness: evidence from US population studies. PLoS One. 2013 Apr 24;8(4):e61955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahfouz RZ, Jankowska A, Ebrahem Q, Gu X, Visconte V, Tabarroki A, Terse P, Covey J, Chan K, Ling Y, Engelke KJ, Sekeres MA, Tiu R, Maciejewski J, Radivoyevitch T, Saunthararajah Y. Increased CDA expression/activity in males contributes to decreased cytidine analog half-life and likely contributes to worse outcomes with 5-azacytidine or decitabine therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2013 Feb 15;19(4):938–48. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1722. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1722. Epub 2013 Jan 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nösslinger T, Tüchler H, Germing U, Sperr WR, Krieger O, Haase D, Lübbert M, Stauder R, Giagounidis A, Valent P, Pfeilstöcker M. Prognostic impact of age and gender in 897 untreated patients with primary myelodysplastic syndromes. Ann Oncol. 2010 Jan;21(1):120–5. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp264. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp264. Epub 2009 Jul 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xin L, Wan-jun S, Zeng-jun L, Yao-zhong Z, Yun-tao L, Yan L, Chang-chun W, Qiao-chuan L, Ren-chi Y, Ming-zhe H, Jian-xiang W, Lu-gui Q. A survival study and prognostic factors analysis on acute promyelocytic leukemia at a single center. Leuk Res. 2007 Jun;31(6):765–71. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2006.07.028. Epub 2006 Sep 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ravandi F, Cortes JE, Jones D, Faderl S, Garcia-Manero G, Konopleva MY, O’Brien S, Estrov Z, Borthakur G, Thomas D, Pierce SR, Brandt M, Byrd A, Bekele BN, Pratz K, Luthra R, Levis M, Andreeff M, Kantarjian HM. Phase I/II study of combination therapy with sorafenib, idarubicin, and cytarabine in younger patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Apr 10;28(11):1856–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4888. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4888. Epub 2010 Mar 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strom SS, Estey E, Outschoorn UM, Garcia-Manero G. Acute myeloid leukemia outcome: role of nucleotide excision repair polymorphisms in intermediate risk patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010 Apr;51(4):598–605. doi: 10.3109/10428190903582804. doi: 10.3109/10428190903582804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katz SJ. Cancer Care Delivery Research and the National Cancer Institute SEER Program: Challenges and Opportunities. JAMA Oncol. 2015 Aug 1;1(5):677–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0764. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park HS, Lloyd S, Decker RH, Wilson LD, Yu JB. Limitations and biases of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Curr Probl Cancer. 2012 Jul-Aug;36(4):216–24. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2012.03.011. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2012.03.011. Epub 2012 Apr 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu JB, Gross CP, Wilson LD, Smith BD. NCI SEER public-use data: applications and limitations in oncology research. Oncology (Williston Park) 2009 Mar;23(3):288–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]