Abstract

Environmental stimuli associated with drug use can take on conditioned properties capable of promoting drug-seeking behaviors during abstinence. This study investigated the relative importance of the amount of reinforced responding, number of cocaine-stimulus pairings, total cocaine intake, and reinforcing effectiveness of the self-administered dose of cocaine to the conditioned reinforcing effectiveness of cocaine-associated stimuli (CS). Male rats were trained to self-administer cocaine (0.1 [small] or 1.0 mg/kg/inf [large]) under a fixed ratio schedule of reinforcement. A progressive ratio (PR) schedule was used to quantify the reinforcing effectiveness of each dose of cocaine, as well as the conditioned reinforcing effectiveness of the CS following treatment with saline or the dopamine D2-like receptor agonist pramipexole (0.1-3.2 mg/kg). The large dose of cocaine maintained larger final ratios and greater levels of cocaine intake, whereas the small dose resulted in more cocaine-CS pairings. The total amount of responding was comparable between groups. During PR tests of conditioned reinforcement, pramipexole increased responding for CS presentations in both groups; however, the final ratio completed was significantly greater in large- as compared to small-dose group. In addition to highlighting a central role for dopamine D2-like receptors in modulating the effectiveness of cocaine-paired stimuli to reinforce behavior, these results suggest that conditioned reinforcing effectiveness is primarily determined by the reinforcing effectiveness of the self-administered dose of cocaine and/or total cocaine intake, and not the total amount of responding or number cocaine-stimulus pairings. These findings have implications for understanding how different patterns of drug-taking might impact vulnerability to relapse.

Keywords: Conditioned Reinforcement, Dopamine D2-like Receptors, Pramipexole, Cocaine Self-Administration

1. Introduction

Drug abuse is a serious public health problem characterized by high rates of relapse, even after repeated attempts to abstain from drug use. Mounting evidence suggests that dopamine D2-like (D2, D3 and D4) receptors mediate, at least in part, a variety of abuse-related behaviors, including those impacting vulnerability to relapse (Newman et al 2005; Heidbreder et al. 2005; Everitt et al. 2008; Heidbreder and Newman 2010). Although numerous factors likely contribute to relapse, it is now well established that previously neutral environmental stimuli can take on powerful conditioned properties that might serve to promote relapse-related behaviors in laboratory animals (Davis and Smith, 1976; de Wit and Stewart, 1983; Goldberg et al., 1979) and humans (O’Brien et al. 1977; Childress et al. 1988; Volkow et al. 2006). Over the past 40 years, procedures have been developed to investigate factors important to relapse, with reinstatement procedures used widely to model relapse in laboratory animals (e.g., de Wit and Stewart 1983; Epstein et al. 2006; Bossert et al. 2013). These most commonly use non-contingent drug infusions (primes) and/or response contingent presentations of stimuli previously paired with drug self-administration (e.g., brief presentations of lights, tones, etc.) to increase (i.e., reinstate) an extinguished drug-taking response. In addition to investigating neural circuits believed to be important to relapse, reinstatement models have also been used to investigate the neuropharmacology of relapse by assessing the effectiveness of receptor-specific drugs to modulate the reinstatement response.

While the capacity of a drug to reduce the reinstatement of responding in animals suggests that it could reduce relapse in humans, it is also important to evaluate the effectiveness of receptor-specific drugs to stimulate extinguished responding. In addition to providing some degree of target validation (i.e., if an antagonist at some receptor inhibits reinstatement, then an agonist at the same receptor might be predicted to stimulate reinstatement), this type of approach also provides the opportunity to characterize the relative importance of specific receptors, or receptor systems, that are involved in mediating the conditioned properties of drug-associated stimuli that might function to promote relapse. Indeed, convergent evidence suggests that dopamine D2-like receptors (among others) play an important role in mediating the reinstatement of responding by drug-associated stimuli (i.e., D3 receptor-preferring antagonists inhibit reinstatement and D3 receptor-preferring agonists enhance reinstatement; Vorel et al. 2002; Cervo et al. 2003; Gilbert et al. 2005; Collins and Woods 2009; Collins et al. 2012a).

Based on the premise that the strength of the conditioned reinforcing properties of drug-associated stimuli is proportional to their likelihood of promoting relapse-related behaviors, we have recently developed a reinstatement-like procedure that uses a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement to quantify the conditioned reinforcing effectiveness of drug-associated stimuli (Collins et al. 2012a). Those studies also investigated the role of dopamine D2-like receptors in mediating the conditioned reinforcing effects of cocaine-associated stimuli, and although they provided evidence to support a role for dopamine D3 (and/or D2) receptors in modulating the conditioned reinforcing effectiveness of cocaine-associated stimuli, the degree to which conditioned reinforcing effectiveness is influenced by the pharmacological, behavioral, or reinforcement history of a subject remains unclear.

The current study was aimed at identifying the specific aspect(s) of a cocaine-reinforcement history that impacts the conditioned reinforcing effectiveness of cocaine-associated stimuli, and thus their capacity to promote relapse-related behaviors in rats. Specifically, these studies investigated how differences in the (1) total amount of responding, (2) number of cocaine-stimulus pairings, (3) total cocaine intake, and (4) reinforcing effectiveness of the self-administered dose of cocaine impact the strength of relapse-related behaviors in rats pretreated with saline or pramipexole.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Subjects

Twelve adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (275-300 g) were obtained from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN), and individually housed for the duration of the study in a temperature- and light-controlled vivarium (24°C; 14/10hr light/dark cycle). Rats were maintained with free access to tap water and Purina rat chow. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and the Eighth Edition of the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 2010).

2.2 Surgery

Rats were surgically prepared with a chronic indwelling catheter in the left femoral vein as previously described (Collins et al. 2012a; Collins et al. 2012b) under 2% isoflourane anesthesia. Catheters were passed under the skin and attached to a vascular access button (VAB95BS; Instech Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). Rats were allowed 5-7 days to recover, and catheters were flushed daily with 0.2 ml of heparinized saline (100 U/ml) during recovery.

2.3 Apparatus and Stimuli Conditions

Experimental sessions were conducted in standard operant conditioning chambers (30.5 cm W×24 cm D×21 cm H; Med Associates Inc., St. Albans, VT) housed inside sound attenuating cubicles. Each chamber was equipped with two response levers located 6.8 cm above the grid floor and 1.3 cm from the right or left wall (ENV-110M; Med Associates Inc.). Visual stimuli were provided by two sets of green, yellow, and red LED lights (ENV-222M; Med Associates Inc.), one located above each of the two levers, and a white house light (ENV-221M; Med Associates Inc.) located at the top center of the opposite wall. Auditory stimuli were provided by a multiple tone generator connected to a speaker (ENV-223, ENV-224DM; Med Associates Inc.) mounted in the upper left corner of the back wall of the chamber. Illumination of the yellow LED above the active lever (left or right counterbalanced across rats) served as the discriminative stimulus (SD). The cocaine-associated stimulus (CS) was coincident with the start of the cocaine infusion and lasted 5-s. The CS consisted of the illumination of the green, yellow and red LEDs above the active lever, illumination of the houselight, and presentation of a 4 kHz tone at 15 dB above background. Drug solutions were delivered by a variable speed syringe pump (PHM-107; Med Associates Inc.) through Tygon® tubing connected to a stainless steel fluid swivel (375/22; Instech Laboratories Inc.) and spring tether (VAB95T; Instech Laboratories Inc.) which was held in place by a counterbalanced arm.

2.4 Fixed Ratio: Training Procedures

Two groups of rats (n=6/group) were randomly assigned to self-administer either a small (0.1 mg/kg/inf) or large (1.0 mg/kg/inf) dose of cocaine, and these dosing assignments remained in place for the duration of self-administration phase of the study (i.e., each rat self-administered only 0.1 or 1.0 mg/kg/inf cocaine). Initially, responding was reinforced according to a schedule of continuous reinforcement during daily 90-min sessions (see Figure 1 for a schema depicting training and testing conditions). During this phase of the study each response on the active lever resulted in a 0.5-sec infusion paired with a 5-sec presentation of the light-tone CS. These conditions remained in place for a minimum of 7 sessions and a maximum of 12 sessions and until rats earned at least 60 infusions of 0.1 mg/kg/inf or 10 infusions of 1.0 mg/kg/inf cocaine during two consecutive sessions. Responses during the CS presentation were recorded, but had no scheduled consequence (i.e., a 5-sec timeout [TO]). The response requirement was gradually increased from 1 to 3 to 5 to 10 with each fixed ratio (FR) in place for 5 consecutive sessions. Responses on the inactive lever were recorded, but had no scheduled consequence. One rat failed to acquire responding for 0.1 mg/kg/inf cocaine and was removed from the study.

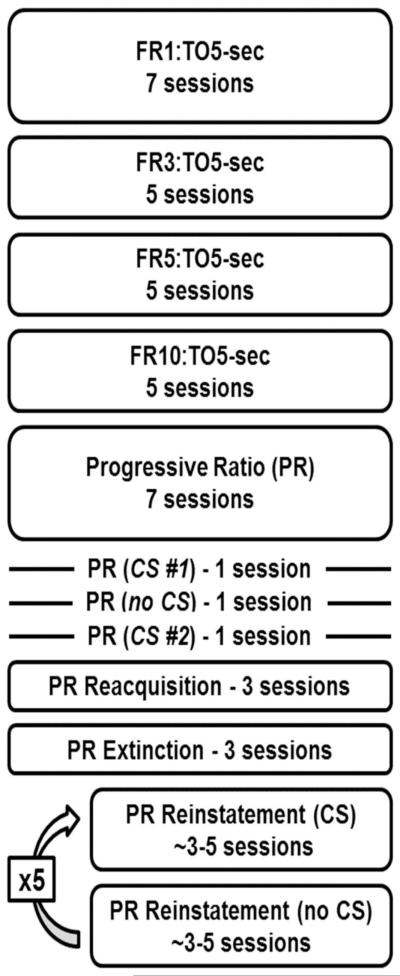

Fig. 1.

Schema depicting the order and duration of training and testing conditions. Both groups of rats completed all experimental procedures. Cycles of PR reinstatement with and without response contingent presentation of the CS were conducted 5 times, with the effects of pramipexole (0.1, 0.32, 1 and 3.2 mg/kg; IP) and saline examined in random order.

2.5 Progressive Ratio: Training Procedures

After 5 sessions of responding under a FR10:TO 5-sec schedule of reinforcement, all rats were transitioned to a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement as previously described (Collins et al., 2012a). Under this procedure, ratios incremented exponentially (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 15, 20, 25, 32, 40, 50, 62, 77, 95, 118, 145, 178, 219, 268, 328, 402, 492, 603, 737, 901, 1102, etc.) based on the equation (Ratio=[5e^(inf#* 0.2)]-5) described by Richardson and Roberts (1996). Sessions lasted a maximum of 4 hrs, but were terminated if a ratio was not completed within 45 min (i.e., 45-min limited hold).

Completion of the ratio requirement resulted in the delivery of the assigned unit dose of cocaine (0.1 or 1.0 mg/kg/inf) paired with a 5-sec presentation of the light-tone CS. These conditions remained in place for 7 consecutive sessions. To test for the importance of the CS to the reinforcing effectiveness of the cocaine-CS complex, a single-session test (no CS) was performed in which the SD was presented and ratio completion resulted in the delivery of the assigned unit dose of cocaine in the absence of the CS. Subsequently, the CS was returned to the contingency and rats could respond for the cocaine-CS complex for three additional sessions.

2.6 Progressive Ratio: Extinction and Responding for Cocaine-associated Stimuli

After recovery of baseline levels of PR responding, all rats were subjected to extinction conditions in which the SD (i.e., yellow LED above active lever) was presented, but responding did not produce cocaine infusions or presentation of the CS. Although responding no longer produced cocaine or the CS, the 45-min limited hold remained in place and lever presses continued to progress the ratio requirement and extend the duration of the session. Extinction conditions remained in place for at least 3 sessions and until the total number of responses had fallen to <20% of baseline (i.e., mean of last 3 sessions in which cocaine was available) for two consecutive sessions. Once extinction criteria were met, rats entered the final phase of the study during which illumination of the SD signaled the start of the session and completion of PR response requirements resulted in either the 5-sec presentation of the previously cocaine-paired stimuli (CS condition), or had no scheduled consequence (no CS condition; the SD remained illuminated). Rats were not allowed to self-administer cocaine for the remainder of the experimental procedures.

During this phase of the study, the effectiveness of the CS to maintain PR responding was evaluated following treatment with saline or the clinically-used dopamine D3-preferring, D2-like receptor agonist, pramipexole (0.1, 0.32, 1.0 and 3.2 mg/kg; intra-peritoneal [IP]). Each treatment (saline or pramipexole) was evaluated under both the CS condition and the no CS condition, with the CS condition always tested first. Each condition was in place for at least 3 consecutive sessions and until responding met the following stability criteria: (1) the total number of ratios completed in 2 consecutive sessions did not differ by more than two; and (2) no increasing or decreasing trend in the number of ratios completed. Thus each dose of pramipexole was tested for at least 6 consecutive sessions. The order in which pramipexole doses and saline were administered was determined at random.

2.7 Drugs

Pramipexole dihydrochloride was purchased from Tocris (Minneapolis, MN, USA), and cocaine hydrochloride was provided by the Drug Supply Program at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Bethesda, MD). Both pramipexole and cocaine were dissolved in sterile, physiologic saline. Cocaine was administered intravenously (IV) in a volume of 0.1 ml/kg, whereas pramipexole was administered IP in a volume of 1 ml/kg.

2.8 Data Analysis

Cocaine self-administration data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.) of the number of reinforced responses, the mean (± S.E.M.) number of cocaine-CS pairings, and the mean (± S.E.M.) cocaine intake (mg/kg/session). Unpaired, two-tailed t-tests were used to compare the total amount of responding, total number of cocaine-CS pairings, total cocaine intake, and final ratio completed for cocaine between the small-dose and large-dose groups of rats. In order to determine if removing the CS from the contingency affected the reinforcing effectiveness of cocaine, paired, two-tailed t-tests were used to compare the number of infusions earned, and the final ratio completed, during the CS #1 and no CS conditions, and the CS #1 and CS #2 conditions (within group, between condition). Unpaired, two-tailed t-tests were used to compare the number of infusions earned, and the final ratio completed, between the small- and large-dose groups during the CS #1 and no CS conditions (between group, within condition).

Data from the pramipexole portion of the experiment are presented as the mean (± S.E.M.) of the final ratio completed and the total session duration for both the CS and no CS conditions. Two-way, repeated measure ANOVAs with post-hoc Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests were used to determine if the final ratio completed or total session duration varied as a function of cocaine history and pramipexole dose (repeated measure), or as a function of stimulus condition (CS versus no CS) and pramipexole dose (repeated measure). The maximum final ratio completed and session duration for each rat (regardless of dose) during the pramipexole phase was used as the Emax for each endpoint. The Emax served as the 100% effect level, with data from remaining doses normalized to this effect level for individual rats. Data points spanning the 20% and 80% effect levels were then analyzed by linear regression to determine the log dose necessary to produce a 50% effect (ED50). Emax and ED50 values obtained for the small- and large-dose groups were compared with unpaired, two-tailed t-tests. Six rats contributed to the data for the large-dose group, and 5 rats contributed to the data for the small-dose group. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (La Jolla, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1 Acquisition of responding

Five of the six rats that self-administered 0.1 mg/kg/inf cocaine acquired responding by the end of the 12-day period (defined by 2 consecutive sessions in which at least 60 infusion were earned), with a mean of 7.6 ± 1.2 sessions required to satisfy this criterion. All six of the rats that self-administered 1.0 mg/kg/inf cocaine acquired responding (defined as 2 consecutive sessions in which at least 10 infusions were earned), with a mean of 5.7 ± 0.6 sessions required to satisfy this criterion. Moderate levels of responding were observed on the inactive lever during the first few sessions for both groups of rats; however, all rats made >80% of responses on the active lever by the end of the acquisition period.

3.2 Cocaine self-administration history

As shown in Figure 2, increasing the FR requirement (from 1 to 10) resulted in a persistent increase in the amount of responding in both groups of rats with cocaine intakes of approximately 10 and 16 mg/kg/session for the small-dose and large-dose groups, respectively. Compared with the large-dose group, rats from the small-dose group made 6.4-fold more cocaine-reinforced responses and were exposed to 6.4-fold more cocaine-CS pairings during the FR phase of the study (9737.4 ± 1709.1 versus 1532.2 ± 78.7 responses, and 1947.6 ± 251.0 versus 306.7 ± 13.3 cocaine-CS pairings); however, rats from the large-dose group self-administered 1.6-fold more cocaine than rats from the small-dose group (306.7 ± 13.3 versus 194.8 ± 25.8 mg/kg). Consistent with larger unit doses of cocaine functioning as more effective reinforcers, the mean final ratio maintained by 1.0 mg/kg/inf of cocaine (281.8 ± 77.9) during the PR phase of the study was 8.5-times greater than that maintained by 0.1 mg/kg/inf of cocaine (33.6 ± 1.6).

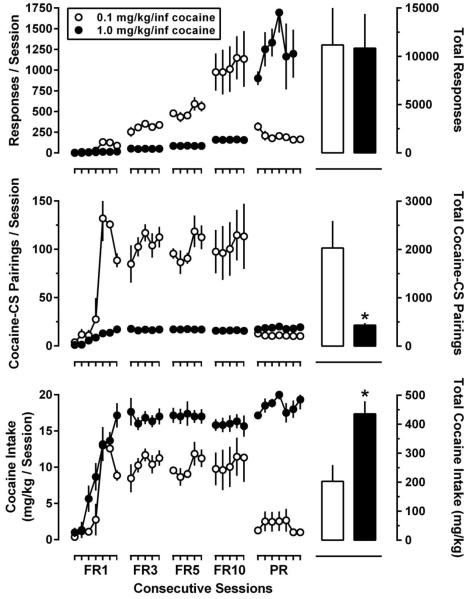

Fig. 2.

Cocaine self-administration in rats responding for one of two unit doses of cocaine [0.1 mg/kg/inf (open symbols; small-dose group; n=5) or 1.0 mg/kg/inf (closed symbols; large-dose group; n=6)]. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. of the total number of reinforced responses (top panel), the total number of cocaine-CS pairings (middle panel), and the total cocaine intake (mg/kg) for each session (bottom panel). Data plotted on the left ordinate represent mean ± S.E.M. of the totals for each daily 90-min session in which cocaine infusions were delivered according to a FR (1, 3, 5, 10) or PR schedule of reinforcement. Data plotted on the right ordinate represent the mean ± S.E.M. of the total number of reinforced responses (top panel), cocaine-CS pairings (middle panel), and cocaine intake (mg/kg; bottom panel) for the duration of the self-administration phase of the study (i.e., FR1, FR3, FR5, FR10, and PR). *, p < 0.05. Significant differences in the total amount of reinforced responding, cocaine-CS pairings, or cocaine intake as determined by unpaired, two-tailed t-tests.

The sum total for cocaine-reinforced responses, cocaine-CS pairings, and cocaine intake during the FR and PR phases of the experiment are shown in Figure 2 (bar graphs). Even though the total amount of responding did not differ between the small- and large-dose groups, significant differences between the two groups were observed with respect to cocaine-CS pairings and cocaine intake. Specifically, rats that self-administered 0.1 mg/kg/inf of cocaine were exposed to 4.7-times more discrete cocaine-CS pairings while earning 2.1-times less cocaine than rats that self-administered 1.0 mg/kg/inf of cocaine. Once larger response requirements were imposed (FR3, FR5, FR10, PR), responding on the inactive lever was rarely observed, with >95% of responding occurring on the active lever, regardless of dosing condition.

3.3 Importance of the CS to the maintenance of responding

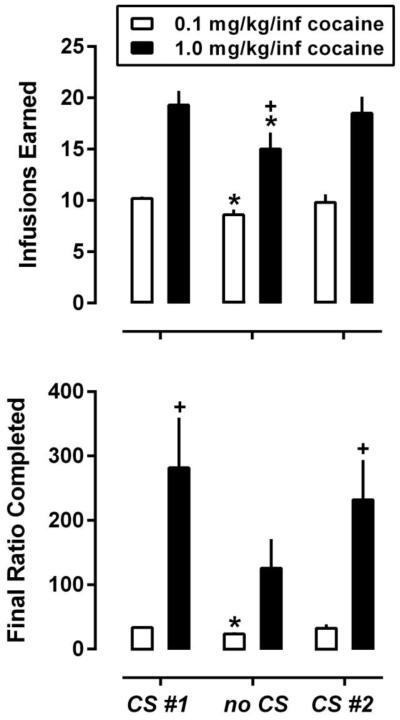

As shown in Figure 3, removing the CS from the contingency significantly reduced the number of cocaine infusions earned, regardless of the unit dose of cocaine available for infusion (P<0.05 for both groups). Although decreases in the number of infusions were observed in both the small- and large-dose groups of rats, a significant reduction in the final ratio completed was only observed in the small-dose group (P<0.05). Upon reintroduction of the CS, baseline performance was recovered in both the small- and large-dose groups. Omission of the CS did not affect the already low levels of inactive lever responding (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

PR performance during sessions in which infusions of 0.1 mg/kg (open bars) or 1.0 mg/kg (closed bars) were delivered in conjunction with the CS (CS #1 and CS #2) or in the absence of CS presentation (no CS). Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. number of infusions earned (top panel) and mean ± S.E.M. of the final ratio completed (bottom panel) for the small-dose (n=5) and large-dose (n=6) groups during the final session that met stability criteria. *, P<0.05; difference from cocaine CS #1 as determined by paired, two-tailed t-test (within group, between condition). +, P<0.05; difference from small-dose group as determined by unpaired, two-tailed t-test (between group, within condition).

3.4 Conditioned reinforcing effects of the CS: interactions with pramipexole

When cocaine and the CS were removed from the contingency, responding decreased rapidly with all rats meeting extinction criteria within 3 sessions. Although the duration of extinction sessions decreased over days, there were no differences in the mean durations of extinction sessions for rats that previously self-administered 0.1 mg/kg/inf (61.9 ± 5.0 min) or 1.0 mg/kg/inf cocaine (60.1 ± 2.1 min). Response contingent presentation of the CS (following saline treatment) maintained moderate levels of PR responding in both the small- and large-dose groups of rats (~20 responses and ~4 CS presentations). Removal or the CS from the contingency decreased responding in both groups (~5 responses and ~2 ratios completed). Pretreatment with pramipexole resulted in both groups of rats exhibiting high rates of CS-maintained responding. As shown in Figure 4 (upper left panel), pramipexole dose dependently increased the final ratio completed for CS presentation, an effect that was also dependent upon the unit dose of cocaine with which the CS was previously paired (pramipexole dose: F[4,36]=8.1, P<0.0001; cocaine dose: F[1,9]=15.8, P<0.01). A similar dose-dependent effect of pramipexole was observed on the final session duration (Figure 4; lower left panel); however, this effect did not differ as a function of the unit dose of cocaine with which the CS was previously paired (pramipexole dose: F[4,36]=18.8, P<0.0001). The majority of sessions for the small-dose group were terminated by the limited hold elapsing (i.e., they failed to complete a ratio within 45 min), whereas when the large-dose group was treated with 0.32 or 1.0 mg/kg of pramipexole all but two sessions were terminated at the predetermined, maximum session duration of 240 min (i.e., rats did not contact the 45-min limited hold). For both groups of rats, responding on the inactive lever remained low throughout tests of conditioned reinforcement, with >95% of responding occurring on the cocaine-associated lever, regardless of dosing condition.

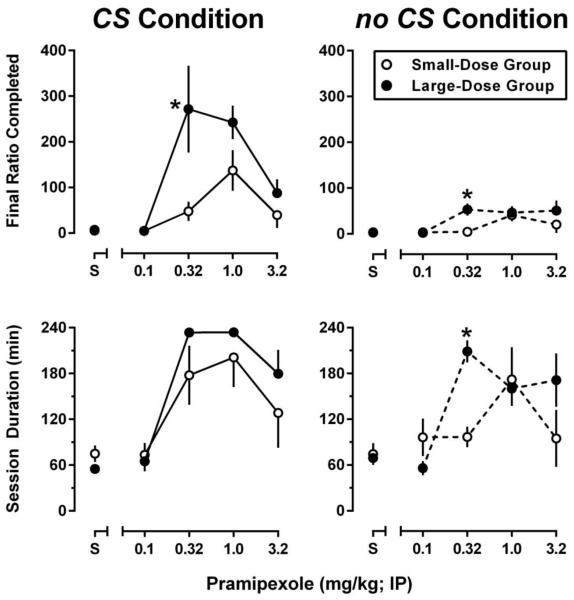

Fig. 4.

PR performance during sessions in which rats were pretreated with saline or pramipexole (0.1-3.2 mg/kg; IP) and completion of ratio requirements resulted in either a 5-sec timeout coincident with the presentation of the cocaine-associated stimuli (CS condition), or an un-signaled 5-sec timeout (no CS condition). Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. of the final ratio completed (top panels) and session duration (bottom panels) for rats from the small-dose (open symbols; 0.1 mg/kg/inf; n=5) and large-dose (closed symbols; 1.0 mg/kg/inf; n=6) groups during the final session that met stability criteria. *, P<0.05. Significant differences in the final ratio completed or session duration between the small- and large-dose groups of rats as determined by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures and post-hoc Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests.

In order to test whether the high levels of responding observed during the CS condition were due to the conditioned reinforcing effects of the CS, the effects of pramipexole were also evaluated during sessions in which the SD was presented, but ratio completion failed to result in CS presentation (Figure 4; right panels). Although pramipexole continued to produce dose dependent increases in responding (i.e., final ratio completed) in both groups of rats (pramipexole dose: F[4,36]=5.7, P<0.01), there was no main effect of training dose of cocaine. When compared to the final ratio completed under the CS condition (within group, between condition) there was a significant main effect of both CS condition and pramipexole dose in both the small- (CS: F[1,8]=6.7, P<0.05; pramipexole dose: F[4,32]=6.5, P<0.001) and large-dose groups (CS: F[1,10]=31.6, P<0.001; pramipexole dose: F[4,40]=8.3, P<0.001); however, a CS×pramipexole dose interaction was observed only in the large-dose group of rats (interaction: F[4,40]=4.2; P<0.01). Unlike the decreases in final ratio completed, removal of the CS from the contingency did not significantly impact the total session duration; however, a main effect of pramipexole dose was still observed in both the small- (pramipexole dose: F[4,32]=4.4, P<0.01), and large-dose groups (pramipexole dose: F[4,32]=4.4, P<0.01). Omission of CS presentations did not affect responding on the inactive lever.

Interactions between pramipexole and the conditioned reinforcing effects of the CS were further characterized by identifying the largest ratio completed by each rat under the CS and no CS conditions, and setting this value as their 100% effect level (Emax), thus allowing for normalization and analysis of the pramipexole dose-response curves by linear regression. Although the potency (ED50) for pramipexole to enhance CS-maintained responding did not differ significantly between groups, the unit dose of cocaine did impact the magnitude (Emax) of the conditioned reinforcing effects of the CS, with the CS that was previously paired with 1.0 mg/kg/inf cocaine maintaining significantly larger ratios than the CS that was previously paired with 0.1 mg/kg/inf cocaine (Table 1). Omitting the CS significantly reduced the maximum ratio completed (irrespective of pramipexole dose) in both the small- and large-dose groups of rats, and the maximal ratio completed under the no CS condition did not differ between groups. Finally, within group comparisons of potency across CS condition revealed a reduction in the potency of pramipexole only when the CS was omitted for the small-dose group of rats.

Table 1.

Potency and effectiveness of pramipexole to stimulate PR responding for presentation of the CS.

| Small-dose Group | Large-dose Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Ratio Completed (S.E.M.) |

ED50

mg/kg (95% CL) |

Maximum Ratio Completed (S.E.M.) |

ED50

mg/kg (95% CL) |

|

| Condition | ||||

| CS | 149.6 (35.7) | 0.35 (0.18-0.51) | 358.2 (77.7)b | 0.21 (0.18-0.24) |

| no CS | 44.4 (15.9)a | 0.55 (0.51-0.59)a | 80.7 (15.2)a | 0.27 (0.17-0.35)b |

, P<0.05; difference from CS condition as determined by paired t-test (within group, between condition).

, P<0.05; difference from small-dose group as determined by unpaired, two-tailed t-test (between group, within condition).

4. Discussion

It is now well established that dopamine systems play a crucial role in mediating the conditioned effects of stimuli associated with food and drug (e.g., Horvitz, 2009; Ranaldi, 2014; Schultz, 2001). The current experiment builds on a series of studies investigating the relationship between the conditioned reinforcing effects of stimuli associated with drug reinforcement and dopamine D2-like (D2, D3, and D4) receptors in rats with various pharmacologic and reinforcement histories (Bertz et al., 2014; Collins and Woods, 2009, 2007; Collins et al., 2012a). Consistent with these reports, and others investigating the impact of pharmacologic and reinforcement histories on the reinstatement of extinguished responding (Zhang et al. 2004; Fuchs et al. 2005; Kippin et al. 2006), the current study provides direct evidence to suggest that the effectiveness of conditioned stimuli to reinforce behavior is more strongly related to pharmacological factors (i.e., reinforcing effectiveness of the self-administered dose and total drug intake) than it is to behavioral factors (i.e., amount of reinforced responding and number of reinforcer-stimulus pairings). In addition, and consistent with our previous findings (Collins and Woods 2009; Collins et al. 2012a), the current study provides clear evidence that activation of dopamine D2-like receptors has a dual effect to (1) enhance the conditioned reinforcing effectiveness of the CS and (2) induce low levels of perseverative behavior previously associated with drug reinforcement.

Previous studies suggest that a variety of factors (access duration, dose, total responding, total drug intake, etc.) are positively correlated with the effectiveness of non-contingent infusions (primes) of cocaine to reinstate a response previously reinforced by cocaine (Deroche et al. 1999; Mantsch et al. 2004; Perry et al. 2006; Knackstedt and Kalivas 2007; Keiflin et al. 2008). However, less is known about the factors that determine the effectiveness of cocaine-associated stimuli to reinstate or reinforce responding. This study extends previous work (Collins et al. 2012a), to test the notion that the conditioned reinforcing effectiveness of cocaine-associated stimuli is positively correlated with reinforcing effectiveness of the primary reinforcer with which they were paired. Accordingly, rats self-administered one of two unit doses of cocaine (either 0.1 or 1.0 mg/kg/inf) and the effectiveness of the cocaine-associated stimuli to maintain responding was evaluated during periods in which cocaine was no longer available. These conditions established two groups of rats with distinct behavioral and reinforcement histories that differed with respect to the number of cocaine-CS pairings (small-dose group > large-dose group), the reinforcing effectiveness of the unit dose of cocaine (large-dose group > small-dose group), and total cocaine intake (large-dose group > small-dose group), while the total amount of cocaine-reinforced responding was comparable between groups. Accordingly, it is possible to make the following predictions: (1) if the total amount of reinforced responding is the determining factor, then the conditioned reinforcing effectiveness of the CS should be equivalent in the small- and large-dose groups; (2) if the total number of cocaine-stimulus pairings is the determining factor, then the conditioned reinforcing effectiveness of the CS should be greater in the small-dose group; (3) if the reinforcing effectiveness of the unit dose of cocaine is the determining factor, then the conditioned reinforcing effectiveness of the CS should be greater in the large-dose group; and (4) if the total cocaine intake is the determining factor, then the conditioned reinforcing effectiveness of the CS should be greater in the large-dose group.

4.1 Total amount of responding as a determinant of conditioned reinforcing effectiveness

Several lines of evidence suggest that the effectiveness of drug-associated stimuli to reinstate or reinforce responding is not related to the total amount of reinforced responses that occurred during drug self-administration. For instance, Fuchs et al. (2005) reported that stimuli paired with moderate doses of cocaine (that maintained moderate levels of responding) were more effective at reinstating responding that stimuli that were paired with small doses of cocaine (that maintained high levels of responding). Kippin et al. (2006) reported differential levels of reinstatement in two groups of rats that had virtually identical histories of cocaine-reinforced responding but differed with respect to whether or not they received supplemental, non-contingent cocaine outside of the self-administration session. Furthermore, by constraining responding for various doses of heroin, Zhang et al. (2004) generated several groups of rats that had similar histories of responding for drug but differed in the magnitude of the reinstatement response when heroin-associated stimuli were presented contingent upon responding. The current study confirms and extends these general findings by demonstrating that even though the total amount of reinforced responding was similar between the large- and small-dose groups, treatment with the dopamine D2-like receptor agonist pramipexole resulted in the CS being a more effective conditioned reinforcer in the large-dose as compared to small-dose groups of rats. However, it should be noted that even though the total amount of responding was comparable between groups, the distribution of these responses across the different phases of self-administration was quite different, with the small-dose group making more responses under FR conditions, and the large-dose group making more responses under PR conditions.

4.2 Total number of cocaine-CS pairings as a determinant of conditioned reinforcing effectiveness

The majority of reinstatement studies establish drug self-administration by using FR schedules of reinforcement, and thus the number of drug-stimulus pairings is usually proportional to the total amount of reinforced responding. Indeed, this was the case for the studies by Zhang et al. (2004), Fuchs et al. (2005), and Kippin et al. (2006) described in section 4.1, and therefore similar conclusions can be drawn with regard to the impact of the number of drug-stimulus pairing on the effectiveness of conditioned stimuli to reinstate and reinforce responding. In the current study the small-dose group was exposed to 4.7-times more discrete cocaine-CS pairings than the large-dose group, yet treatment with the dopamine D2-like receptor agonist pramipexole revealed that the conditioned reinforcing effectiveness of the CS was 2.4-fold greater in the large-dose as compared to small-dose group. These results provide additional strong evidence to suggest that the number of cocaine-CS pairings is not the primary determinant of conditioned reinforcing effectiveness of cocaine-associated stimuli. However, a more direct approach to testing this relationship might be to keep the unit dose of cocaine constant while manipulating the frequency with which the CS is paired with cocaine infusions (i.e., with every infusion, or with every third or fourth infusion).

4.3 Reinforcing effectiveness of the primary reinforcer as a determinant of conditioned reinforcing effectiveness

Larger unit doses of drug are more effective reinforcers than smaller unit doses of the same drug (e.g., Richardson and Roberts, 1996; Rodefer and Carroll, 1999). Thus, it follows that stimuli associated with larger unit doses of drug would take on greater conditioned reinforcing effects and be more effective at reinstating an extinguished drug-taking response. By limiting the number of infusions that could be earned, regardless of unit dose, Zhang et al. (2004) showed that stimuli associated with larger doses of heroin are more effective at reinstating responding than stimuli associated with smaller unit doses. However, these relationships are not always observed. For instance, Fuchs et al. (2005) reported that the relationship between the unit dose of self-administered cocaine and the amount of responding observed during reinstatement tests with the cocaine-paired stimuli was inverted U-shaped in female rats, and relatively flat in male rats. However, those studies evaluated reinstatement under an FR1 schedule of reinforcement which resulted in “low” and “high” levels of reinstatement differing by as little as 25 responses. By using a PR schedule and stimulating responding with the dopamine D2-like receptor agonist pramipexole, the current study provided a more quantitative assessment of conditioned reinforcement, and additional clear evidence to suggest that the conditioned reinforcing effectiveness of drug-associated stimuli is proportional to the reinforcing effectiveness of the drug reinforcer with which it was paired.

4.4 otal drug intake as a determinant of conditioned reinforcing effectiveness

Collectively, the results of several studies support the notion that total drug intake is at least partially involved in determining the effectiveness of drug-associated stimuli to reinstate or reinforce a response that was previously reinforced by drug. As discussed above (sec 4.1), Kippin et al. (2006) reported that increasing the total dose through supplemental, non-contingent cocaine administration increased the effectiveness of cocaine-associated stimuli to reinstate responding. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2004) reported a positive correlation between intake and reinstatement, however, because they manipulated intake by constraining the number infusions that could be earned it is impossible to separate the relative importance of the reinforcing effectiveness of the unit dose from total drug intake (this is also limitation of the current study). Results of studies by Fuchs et al. (2005) and Feltenstein et al. (2012) provide contradictory evidence, and argue against total drug intake as being the primary determinant of the effectiveness of conditioned stimuli to reinstate or reinforce a response that was previously reinforced by drug.

4.5 Conclusions

The current study provides further evidence supporting a crucial role for dopamine D2-like (D2, D3, and D4) receptors in mediating the conditioned reinforcing properties of drug-paired stimuli, and suggest that the effectiveness of these conditioned reinforcers is related to the magnitude of the primary reinforcer with which they were paired, and not the total amount of reinforced responding or the number of drug-CS pairings. Assuming that conditioned reinforcing effectiveness of drug-associated stimuli is positively correlated with the likelihood of their promoting relapse-related behaviors, these studies have implications for understanding how different patterns of drug use might impact vulnerability to relapse. Interestingly, patients treated with pramipexole for symptomatic relief of Parkinson’s disease or restless-leg syndrome are at increased risk for developing a wide variety of impulse control disorders, such as compulsive gambling, compulsive shopping, and hyper-sexuality (Driver-Dunkley et al. 2003; Voon et al. 2007; Weintraub 2008; Holman 2009). In light of the current findings, it is possible that these aberrant, goal-directed behaviors result from a dopamine D2-like receptor mediated enhancement of the conditioned reinforcing effects of environmental stimuli associated with these behaviors; however, further research is required to identify the mechanisms responsible for the development and maintenance of these impulse control disorders.

5. Acknowledgements

CPF is supported by a National Institute on Drug Abuse Senior Scientist Award (K05 DA017918).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

6. References

- Bertz JW, Chen J, Woods JH. Effects of pramipexole on the acquisition of responding with opioid-conditioned reinforcement in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014;232:209–221. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3659-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossert JM, Marchant NJ, Calu DJ, Shaham Y. The reinstatement model of drug relapse: recent neurobiological findings, emerging research topics, and translational research. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;229:453–476. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3120-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervo L, Carnovali F, Stark JA, Mennini T. Cocaine-seeking behavior in response to drug-associated stimuli in rats: involvement of D3 and D2 dopamine receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1150–1159. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress AR, McLellan AT, Ehrman R, O’Brien CP. Classically conditioned responses in opioid and cocaine dependence: a role in relapse? NIDA Res Monogr. 1988;84:25–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Cunningham AR, Chen J, Wang S, Newman AH, Woods JH. Effects of pramipexole on the reinforcing effectiveness of stimuli that were previously paired with cocaine reinforcement in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012a;219:123–135. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2382-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Narasimhan D, Cunningham AR, Zaks ME, Nichols J, Ko M-C, Sunahara RK, Woods JH. Long-lasting effects of a PEGylated mutant cocaine esterase (CocE) on the reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012b;37:1092–1103. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Woods JH. Influence of conditioned reinforcement on the response- maintaining effects of quinpirole in rats. Behav. Pharmacol. 2009;20:492–504. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328330ad9b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Woods JH. Drug and reinforcement history as determinants of the response-maintaining effects of quinpirole in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007;323:599–605. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.123042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis WM, Smith SG. Role of conditioned reinforcers in the initiation, maintenance and extinction of drug-seeking behavior. Pavlov. J. Biol. Sci. 1976;11:222–236. doi: 10.1007/BF03000316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit H, Stewart J. Drug reinstatement of heroin-reinforced responding in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1983;79:29–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00433012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroche V, Le Moal M, Piazza PV. Cocaine self-administration increases the incentive motivational properties of the drug in rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:2731–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver-Dunkley E, Samanta J, Stacy M. Pathological gambling associated with dopamine agonist therapy in Parkinson’s. Neurology. 2003;2:60–61. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000076478.45005.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Preston KL, Stewart J, Shaham Y. Toward a model of drug relapse: an assessment of the validity of the reinstatement procedure. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;189:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0529-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Belin D, Economidou D, Pelloux Y, Dalley JW, Robbins TW. Review. Neural mechanisms underlying the vulnerability to develop compulsive drug-seeking habits and addiction. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2008;363:3125–35. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, Ghee SM, See RE. Nicotine self-administration and reinstatement of nicotine-seeking in male and female rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;121:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Evans KA, Mehta RH, Case JM, See RE. Influence of sex and estrous cyclicity on conditioned cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;179:662–672. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JG, Newman AH, Gardner EL, Ashby CR, Heidbreder CA, Pak AC, Peng X-Q, Xi Z-X. Acute administration of SB-277011A, NGB 2904, or BP 897 inhibits cocaine cue-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in rats: role of dopamine D3 receptors. Synapse. 2005;57:17–28. doi: 10.1002/syn.20152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SR, Spealman RD, Kelleher RT. Enhancement of drug-seeking behavior by environmental stimuli associated with cocaine or morphine injections. Neuropharmacology. 1979;18:1015–1017. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(79)90169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder CA, Gardner EL, Xi Z-X, Thanos PK, Mugnaini M, Hagan JJ, Ashby CR. The role of central dopamine D3 receptors in drug addiction: a review of pharmacological evidence. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2005;49:77–105. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder CA, Newman AH. Current perspectives on selective dopamine D3 receptor antagonists as pharmacotherapeutics for addictions and related disorders. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010;1187:4–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman AJ. Impulse control disorder behaviors associated with pramipexole used to treat fibromyalgia. J. Gambl. Stud. 2009;25:425–431. doi: 10.1007/s10899-009-9123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz JC. Stimulus-response and response-outcome learning mechanisms in the striatum. Behav. Brain Res. 2009;199:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiflin R, Vouillac C, Cador M. Level of operant training rather than cocaine intake predicts level of reinstatement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197:247–61. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippin TE, Fuchs RA, See RE. Contributions of prolonged contingent and noncontingent cocaine exposure to enhanced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;187:60–67. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0386-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knackstedt LA, Kalivas PW. Extended access to cocaine self-administration enhances drug-primed reinstatement but not behavioral sensitization. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007;322:1103–1109. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.122861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantsch JR, Yuferov V, Mathieu-Kia A-M, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Effects of extended access to high versus low cocaine doses on self-administration, cocaine-induced reinstatement and brain mRNA levels in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;175:26–36. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1778-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council . Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. eighth National Academy Press; Washington DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Newman AH, Grundt P, Nader MA. Dopamine D3 receptor partial agonists and antagonists as potential drug abuse therapeutic agents. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:3663–3679. doi: 10.1021/jm040190e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CP, Testa T, O’Brien TJ, Brady JP, Wells B. Conditioned narcotic withdrawal in humans. Science (80) 1977;195:1000–1002. doi: 10.1126/science.841320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Morgan AD, Anker JJ, Dess NK, Carroll ME. Escalation of i.v. cocaine self-administration and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats bred for high and low saccharin intake. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;186:235–245. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0371-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranaldi R. Dopamine and reward seeking: the role of ventral tegmental area. Rev. Neurosci. 2014;25:621–630. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2014-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson NR, Roberts DC. Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1996;66:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodefer JS, Carroll ME. Concurrent progressive-ratio schedules to compare reinforcing effectiveness of different phencyclidine (PCP) concentrations in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;144:163–174. doi: 10.1007/s002130050990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Reward signaling by dopamine neurons. Neuroscientist. 2001;7:293–302. doi: 10.1177/107385840100700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang G, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, Childress A, Jayne M, Ma Y, Wong C. Cocaine cues and dopamine in dorsal striatum: mechanism of craving in cocaine addiction. Neuroscience. 2006;26:6583–6588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1544-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon V, Potenza MN, Thomsen T. Medication-related impulse control and repetitive behaviors in Parkinson’s disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2007;20:484–492. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32826fbc8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorel SR, Ashby CRJ, Paul M, Liu X, Hayes R, Hagan JJ, Middlemiss DN, Stemp G, Gardner EL. Dopamine D3 receptor antagonism inhibits cocaine-seeking and cocaine-enhanced brain reward in rats. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:9595–9603. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09595.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub D. Dopamine and impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 2008;64:93–100. doi: 10.1002/ana.21454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Zhou W, Tang S, Lai M, Liu H, Yang G. Motivation of heroin-seeking elicited by drug-associated cues is related to total amount of heroin exposure during self-administration in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2004;79:291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]