Abstract

Objective

In temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) pathological high frequency oscillations (pHFOs, 200–600 Hz) are present in the hippocampus, especially the dentate gyrus (DG). The pHFOs emerge during a latent period prior to the onset of spontaneous generalized seizures. We used a unilateral suprahippocampal injection of kainic acid (KA) mouse model of TLE to characterize the properties of hippocampal pHFOs during epileptogenesis.

Methods

In awake head-fixed mice, 4–14 days after KA-induced status epilepticus (SE), we recorded local field potentials (LFP) with 64-channel silicon probes spanning from CA1 alveus to the DG hilus, or with glass pipettes in the DC mode in the CA1 str radiatum.

Results

The pHFOs, are observed simultaneously in the CA1 and the DG, or in the DG alone, as early as 4 days post-SE. The pHFOs ride on top of DC deflections, occur during motionless periods, persist through the onset of TLE, and are generated in bursts. Burst parameters remain remarkably constant during epileptogenesis, with a random number of pHFOs generated per burst. In contrast, pHFO duration and spectral dynamics evolve from short events at 4 days post-SE to prolonged discharges with complex spectral characteristics by 14 days post-SE. Simultaneous dural EEG recordings were exceedingly unreliable for detecting hippocampal pHFOs, hence such recordings may deceptively indicate a “silent” period even when massive hippocampal activity is present.

Significance

Our results demonstrate that hippocampal pHFOs exhibit a dynamic evolution during the epileptogenic period following SE, consistent with their role in transitioning to the chronic stage of TLE.

Keywords: Temporal lobe epilepsy, dentate gyrus, CA1, pHFO, pathological high frequency oscillations, latent period, epileptogenesis, kainic acid

Introduction

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is the most common form of acquired epilepsy and typically develops following precipitating insults including head trauma, infection, ischemia, prolonged febrile seizures or status epilepticus (SE) 1; 2. The insults are often followed by several years (humans) or weeks (rodents) of a seizure-free latent period thought to be a time of proconvulsant functional and anatomical reorganization 2–4. The ensuing TLE is progressive in nature, with increasing seizure frequency and anatomical degeneration 4; 5. Recent chronic EEG studies in KA-treated rats demonstrated that subconvulsant electrographic seizures emerge prior to the onset of spontaneous behavioral seizures that can be used to define the onset of an epileptic phenotype 6. Thus, the onset of behavioral seizures is merely the manifestation of ongoing epileptogenic processes 7 that evolve during the latent period. Although Wilder Penfield emphasized that understanding this “silent period of strange ripening” 8 was a fundamental question of acquired epilepsies, over five decades later, still little is known about the mechanisms of epileptogenesis 9.

Pathological high-frequency oscillations (pHFOs) are transient high-frequency LFP oscillations (200–600 Hz) generated in hippocampal and extrahippocampal regions of TLE patients and in rodent models of TLE 10–13. These oscillations have been observed in hippocampal DG, CA3, CA1 regions and in the entorhinal cortex, and are believed to reflect proconvulsant cellular and network abnormalities that accumulate during the latent period, eventually contributing to seizure generation. Studies from TLE patients have shown that pHFOs are most prominent near regions that initiate seizures, and combined structural MRI and depth electrode recordings have revealed that pHFOs are more pronounced in regions of hippocampal sclerosis 14; 15. In vivo and in vitro studies established that pHFOs are generated in highly localized regions within the hippocampus, exhibit spatial stability throughout epileptogenesis, and continue after the onset of behavioral seizures 12; 16. Current evidence posits that pHFOs originate from pathologically interconnected microcircuits that develop during epileptogenesis and continue to play an important role during the chronic phase of epilepsy when they may contribute to ictogenesis.

Hippocampal pHFOs highly correlate with the development of TLE, are generated near regions of pathological anatomy and seizure genesis, but it is still unclear if pHFO properties such as their duration, frequency spectra, or their occurrence in bursts evolve during the latent period of epileptogenesis. If pHFOs reflect a progressive proconvulsant network reorganization during this period, then their temporal and spectral properties should also evolve during epileptogenesis. We used a unilateral KA mouse model of TLE to investigate the temporal and spectral properties of pHFOs in vivo during the latent period. We found that pHFOs emerge in the hippocampus, as early as 4 days post-SE, and persist throughout the latent period. Interestingly, pHFOs are always generated in bursts, but the burst properties are invariant as epileptogenesis evolves. In contrast, pHFOs increase their duration and change their spectral properties during the same period. Given our data, pHFOs recorded in the hippocampus may be reliable biomarkers for the transition period from brain injury (e.g., SE) to chronic epilepsy, and additionally, they may provide a quantitative measure of the precise epileptogenic state after the precipitating insult, thus aiding the evaluation of TLE progress prior to the onset of spontaneous generalized seizures. Remarkably, using dural EEG recordings, the most common recording method in animal studies of epilepsy, we were unable to identify the pronounced pHFOs obvious in our direct hippocampal recordings, demonstrating that dural EEG in animals may be inadequate for discriminating between stages of epileptogenesis.

Methods

Animals

Adult male C57BL/6 mice were housed on a 12h/12h light/dark cycle and provided with food and water ad libitum. All protocols were approved by the University of California, Los Angeles, Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee (ARC) and comply with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Suprahippocampal kainate mouse model of TLE

We adopted a modified unilateral KA mouse model of TLE developed in the laboratory of Dr. Christian Steinhäuser (University of Bonn) 17, an adaptation on a previously described unilateral intrahippocampal KA injection mouse model of TLE 18. We chose this model of TLE over the pilocarpine mouse model for several reasons: 1) It produced reliable and reproducible SE, with a very low (~10%) mortality rate; 2) The resulting KA-induced lesion is reminiscent of human TLE 17, with unilateral hippocampal sclerosis and seizure onset; 3) In our experience, the C57BL/6 mice exhibit spontaneous seizures following a latent period of ~14 days, although this may be shorter in other strains 17.

Surgery and KA-injection

Surgeries were performed under aseptic conditions on male mice weighing 25–30 g (3–4 months of age), anesthetized with isoflurane (1.5 % in 100% O2, 1.25 l/min) and mounted into a Stoelting instrument stereotaxic frame with blunt ear bars. Body temperature was maintained at 37°C using a rectal probe and a water-circulated heating pad. Further details can be found in the Supplemental Methods section.

In vivo local field potential recordings

Local field potential (LFP) recordings were performed in awake, head-fixed animals at different time points after the KA injection (days: 4, 7, 11 and 14). Recordings were started at 4 days post-SE because mice typically require 2–3 days to fully recover from the effects of KA-induced SE. Mice were positioned head-fixed onto a spherical treadmill without anesthesia. The Kwik-Sil protective layer was removed and either a 64-channel silicone probe 19 or single borosilicate glass pipettes (King Precision Glass, Claremont, CA) filled with 150 mM NaCl, were advanced through the preformed holes to target the hippocampus or the CA1 str radiatum, respectively (either ipsilateral, or bilaterally, 1880 μm axially from dura). Further details of the LFP recordings are described in the Supplemental Methods section.

Tissue preparation and imaging

Following the completion of in vivo electrophysiological recording on day 14, mice were deeply anesthetized with Na-pentobarbital (90 mg/kg, i.p.) and transcardially perfused with PBS (0.12 M, pH 7.1), followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were removed and fixed overnight in 4% PFA at 4°C. After rinsing in PBS, brains were cryoprotected for two days in 30% sucrose solution at 4°C, frozen in OCT compound, and 50 μm coronal sections were cut with a cryostat (Leica Microsystems). Granule cell (GC) dispersion and mossy fiber sprouting, classic markers of epileptogenesis 13; 20, were visualized with a DAPI nuclear stain and immunofluorescent labeling of ZnT-3 21, respectively. Sections were incubated in blocking solution containing 10% normal goat serum in Tris buffered saline (TBS; pH 7.3) and 0.3% Triton X-100 for 2 hrs at RT. Slices were rinsed in TBS for 30 min and incubated at RT overnight in primary monoclonal rabbit anti-ZnT3 (1:1000, Synaptic Systems), followed by incubation in goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 (Invitrogen). Slices were mounted on slides using a DAPI-containing mounting medium (Vector Labs) and coverslipped for imaging. Epifluorescent images were obtained using an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with a CCD camera (QImaging, Surrey BC). Images were compiled and analyzed using ImageJ.

pHFO Analysis

pHFOs were detected by band-pass filtering (FIR filter, Igor Pro 6.37) the recordings between 200 – 600 Hz and by calculating the Hilbert transforms of the band-passed traces. The Hilbert transforms were first smoothed by an 80 ms duration boxcar running average algorithm and these smoothed traces served for the detections of pHFOs. The standard deviation (SD) of the smoothed Hilbert transform was calculated for the period of analysis and an event was considered when the smoothed Hilbert magnitude exceeded a threshold of 2.5×SD for a duration of at least 20 ms, ensuring that at least 4 cycles of a pHFO of 200 Hz were contained within the event (ref 23 Suppl Materials). The termination of the event was defined as the point at which the Hilbert magnitude reverted below the threshold, thus yielding the pHFO duration as the difference between these two time points. The pHFOs corresponding to the detected smoothed Hilbert transforms were then identified and individually inspected on the raw and 200–600 Hz filtered traces (Suppl. Fig. 2). The detected pHFOs were then extracted and used for further analysis. Time-frequency analyses were performed using continuous wavelet transform procedures in Igor Pro. The Morlet mother wavelet was used and scales were chosen to reflect frequencies between 1 and 1000 Hz (ω0 = 6). Z-scored wavelet transforms were calculated at each 1 s−1 frequency band were calculated to represent relative changes in magnitude. Warmer colors represent greater Z-scores.

pHFO Burst Analysis

We utilized single channel burst analysis techniques to assess the temporal patterns of pHFOs during epileptogenesis as described in the Supplemental Methods.

Statistical Analyses

Statistics were calculated using GraphPad Prism 6 (La Jolla, CA) and R 3.1.2. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean. Significance level (α) was set to 0.05. For ANOVAs with significance levels below 0.05, post-hoc paired tests (Bonferroni) were performed and corrected for multiple comparisons. Nonparametric statistical analyses, i.e., the Kruskal–Wallis (K-W) test by ranks were used for datasets where normality of the distribution could not be accurately determined.

Results

Suprahippocampal kainate injection recapitulates previously described mouse models of TLE

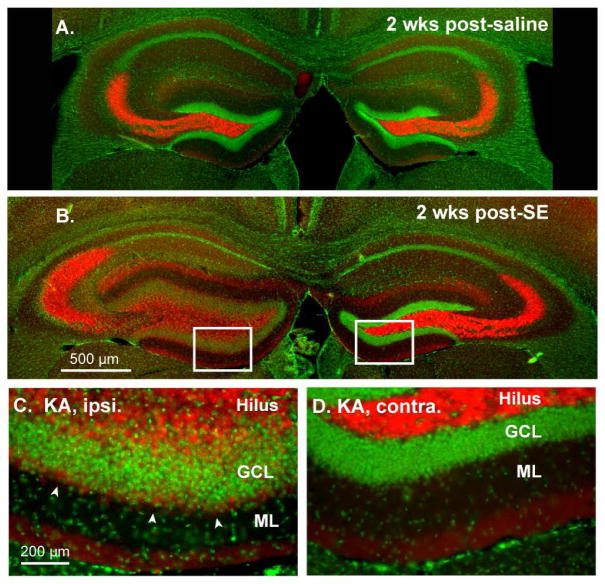

Our unilateral suprahippocampal KA injection mouse model of TLE produced similar histopathology to that previously described 18. Histological analyses of all KA and saline-injected mice were performed 2 wks post-SE. DAPI nuclear labeling of the hippocampi from saline injected mice showed no overt abnormalities, indicating that the saline injection and subsequent repeated electrode insertions over the two-week recording period did not cause significant hippocampal damage (Fig. 1A). In contrast, KA-injected mice exhibited prominent hippocampal sclerosis on the KA-injected side and relatively normal anatomy in the contralateral, uninjected hippocampus (Fig. 1B, left: KA injected, right: uninjected). The KA-injected hippocampus showed significant cell loss in the hilus, CA3 and CA1 regions and prominent GC dispersion, while the contralateral GC layer exhibited normal anatomy (Fig. 1C and D). Strong expression of ZnT-3 in mossy fiber boutons, which reliably labels aberrant mossy fiber synapses (“mossy fiber sprouting”) in the inner third of the molecular layer during epileptogenesis was apparent in the inner molecular layer of the KA-injected hippocampus at two weeks post-SE. The contralateral DG showed no signs of mossy fiber sprouting (Fig. 1C and D, arrows) 18.

Figure 1. Unilateral suprahippocampal KA-injection recapitulates anatomical changes observed in previous models of TLE.

A, DAPI (4′,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole, Dihydrochloride) labeling of cell nuclei (green) and immunofluorescent labeling of mossy fiber boutons with ZnT-3 antibody (red) reveal normal hippocampal anatomy 2 weeks post-saline injection. B, The same labeling revealed significant cell loss in the CA1 and hilar regions on the KA-injected hippocampus (left), prominent GC dispersion, and mossy fiber sprouting (C, arrows) at 2 weeks post-SE. The contralateral, uninjected hippocampus exhibited hilar cell loss but no other overt morphological abnormalities and no detectable mossy fiber sprouting (D). GCL – granule cell layer, ML – molecular layer.

Our immunohistochemical analysis of this model (Fig 1) and observed behavioral seizures (Suppl Fig 3), the suprahippocampal KA injection model of TLE exhibits many characteristics reminiscent of human TLE 17. Importantly, seizures appear to have hippocampal origin, as opposed to other systemic chemoconvulsant models where seizures can initiate in extrahippocampal regions 7; 22.

pHFOs are recorded in both CA1 and DG regions during epileptogenesis

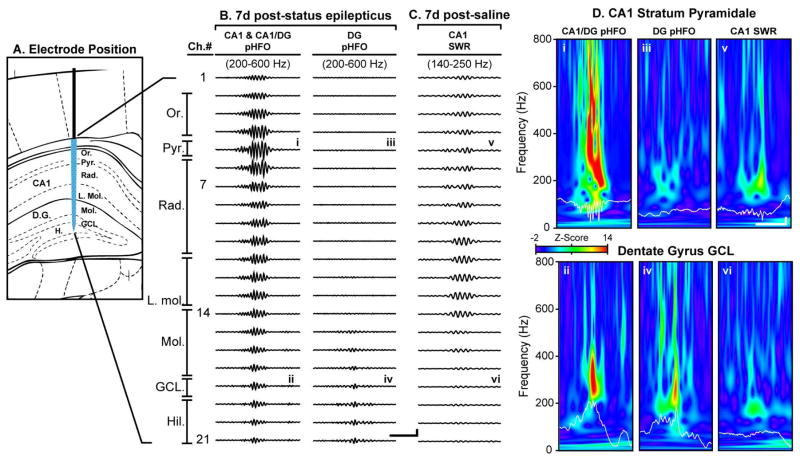

To confirm that the suprahippocampal KA mouse model of TLE also exhibited pHFOs during epileptogenesis we utilized 64 channel multi-electrode silicone probes 19 oriented such that the electrode leads ran through all layers of the CA1 region and into the hilus of the DG (Fig. 2A). Prominent pHFOs were recorded in all mice 7 days post-SE (N = 6) but were not observed in post-saline (N =2) mice. Similar to previous findings in intrahippocampal KA-treated rats 23; 24, we find that pHFOs are generated in both CA1 and DG (Fig. 2B, CA1/DG and DG) regions. Standardized 1000 s epochs were obtained in in four animals at 7 days post-SE. In these recordings we detected a total of 1154 pHFOs with an average frequency of 0.29 ± 0.12 Hz. The largest amplitude pHFOs were present in the CA1 pyramidal cell layer (PCL) and invariably occurred together with pHFOs in the DG (Fig. 2B, CA1/DG pHFOs, i and ii). Although these events were classified as CA1/DG (37 ± 3.9 % of total), they most likely originated in the CA1, as there was a phase reversal of the events in the str. radiatum which then passively propagated from the CA1 to DG. In contrast, 63 ± 3.9 % of the detected pHFOs were observed only within the DG, exhibiting largest amplitudes at the GCL with no corresponding CA1 pHFOs (Fig. 2B, DG only, iii and iv). Additionally, DG only pHFOs exhibited phase reversal at the granule cell layer (GCL) (data not shown). Wavelet analysis of both CA1/DG and DG only pHFOs revealed strong spectral components from 200–600 Hz, characteristic of pHFOs (Fig. 4D). PHFOs were not observed in saline injected mice, though prominent sharp-wave ripples (SWRs) were present in CA1, which possessed spectral components similar to previously reported SWRs (Fig. 2D, v & vi, CA1 SWR) 20; 25.

Figure 2. Spatial distribution of pHFOs and SWR across hippocampal layers.

A, Positioning of the 64-channel silicone probe across the hippocampal layers. The electrode was positioned so that the most superficial leads were outside the hippocampus and the deepest leads targeted the hilus of the dentate gyrus (DG). 21 of 64 channels are shown. B, Two groups of pHFOs were observed in ipsilateral LFP recordings at 7d post-SE: CA1/DG pHFOs and DG-only pHFOs. Example pHFO events are shown for each group in the two left columns. C, No pHFOs were observed in saline-injected mice. However, SWRs were present in the CA1 (note the lower, 140–250 Hz band-pass filter). Note that CA1 SWR do not invade the DG. D, Wavelet transforms and raw LFP records (white trace) for CA1 stratum pyramidale and DG granule cell layer events. The traces are overlaid on the corresponding Z-scored wavelet spectra. D i & ii, CA1/DG pHFO shown in B, column 1. Note the prominent high frequency components (above 200 Hz) in both CA1 and DG wavelets. D iii & iv, DG only pHFO shown in B, column 2. The DG wavelet transform illustrates high frequency components, which are absent in CA1. D v & vi, CA1 SWR recorded from a saline injected mouse. Scale bars are 40 ms and 200 μV.

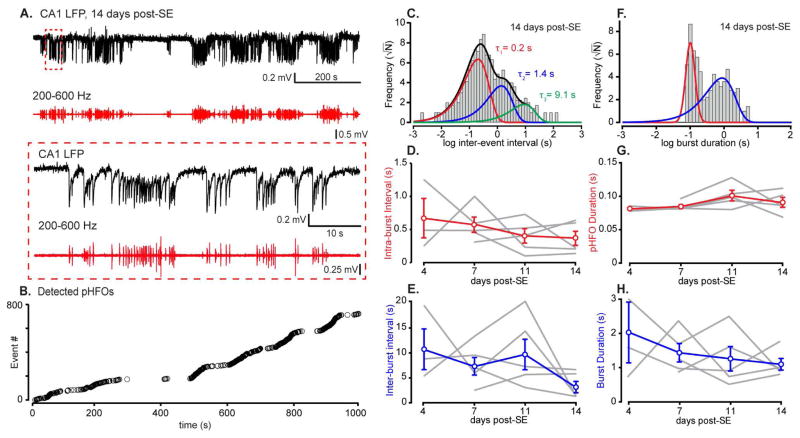

Figure 4. Burst properties of pHFOs.

A, top trace, Raw DC LFP recordings from the CA1 str. radiatum showed prominent periods of pHFO bursting and regions of relative quiescence. Band-pass filtered records (200–600 Hz, A, red trace) and close inspection of LFP records (red box) further illustrated the burst character of pHFOs. B, Detected pHFO events from the 1000 s long record in A show periods of robust pHFO generation (during motionless states) interspersed with periods of pHFO silence, corresponding to times when the animal was moving (also see Suppl. Fig. 4). C, Log-binned pHFO inter-event interval (IEI) histograms exhibited two or three distributions that were well fit with multiple exponential distributions (colored fits) representing intra-burst (red fit), inter-burst (blue fit) and occasionally intra-cluster (green fit) intervals. Intra-burst (D) and inter-burst (E) intervals were 0.52 ± 0.2 s and 7.63 ± 2.5 s, respectively, and showed no significant change from 4 to 14 days post-SE (p > 0.05 for each, one-way ANOVA). F, Burst duration histograms exhibited two distributions, corresponding to the durations of individual pHFOs (left distribution, red fit) and of multi-pHFO bursts (right distribution, blue fit). G & H, Individual pHFO and multi-pHFO durations were consistent throughout the experimental period, with average durations of 90 ± 6.5 ms and 1.43 ± 0.4 s, respectively (p > 0.05 for each, one-way ANOVA).

Properties of pHFOs during epileptogenesis

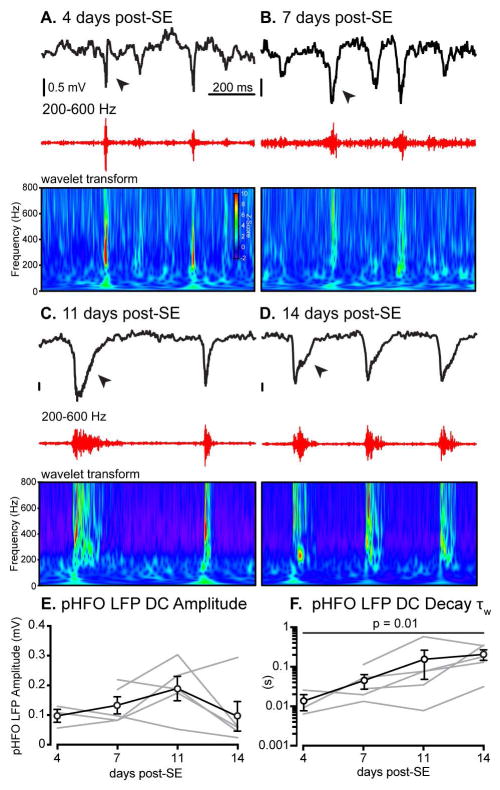

Although pHFOs appear prior to the emergence of chronic seizures, it is unknown if they evolve during the epileptogenesis. To address this, in a different set of 7 KA-injected mice, we recorded DC LFPs in the CA1 str. radiatum using single borosilicate glass electrodes (Fig. 3A–D, black traces) at 4, 7, 11 and 14 days post-SE, during the epileptogenic period. PHFOs were visualized by band-pass filtering between 200–600 Hz (Fig. 3A–D, red traces) and by their spectral characteristics (Fig. 3A–D, wavelet transform). The pHFOs were present at 4 days post-SE in 5 out of 7 KA-injected mice and persisted throughout the two-week recording period (Fig. 3A–D). Previous studies have investigated pHFO properties mostly in AC recordings and high-pass filtered (200–600 Hz) events 13; 23. Recorded in DC mode, pHFOs consistently ride on the top of transient negative LFP deflections (1.33 ± 0.4 mV, Fig. 3A–D, black traces). The amplitude of LFP deflections did not change throughout the epileptogenic period (p = 0.34, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 3E), but the decay time constant of the LFP deflections became more prolonged, from 13.6 ms at 4 days to 206.4 ms at 14 days post-SE (p = 0.01, K-W, Fig. 3A–D, arrows, and 3F). Based on our results in Suppl Fig 5, all subsequent pHFO analyses were done on pHFOs recorded during immobility.

Figure 3. Properties of pHFOs during epileptogenesis.

PHFOs were present in post-SE mice at 4 (n = 3), 7, 11 and 14 days post-SE (n = 5). No pHFOs were detected in saline-injected controls (n = 3). A–D, pHFOs were generated on top of large LFP deflections (black traces, arrows). Band-pass filtered records (200–600 Hz, red traces) revealed pronounced pHFOs near the peak of the LFP deflection and time-frequency analysis with continuous wavelet transform revealed complex spectral dynamics. E, No significant change in LFP DC deflection amplitudes was observed across all time points (133 ± 40 μV, p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA). F, In contrast, the decay time constant of the LFP deflection increased significantly from 13.6 ± 0.6 ms at 4 days post-SE to 206.4 ± 6.0 ms at 14 days post-SE (p = 0.01, K-W).

Temporal dynamics of pHFOs during epileptogenesis

We next assessed the temporal properties of CA1 pHFOs during epileptogenesis. Records from all post-SE animals (N = 5) across all time points revealed that pHFOs are generated in bursts (Fig. 4A and B). To determine if the burst properties of pHFOs evolve during epileptogenesis, we utilized quantification techniques (see Supplemental Methods) customarily used for single channel analyses. The pHFO inter-event interval (IEI) histograms exhibited at least two exponential distributions (Fig. 4C, red and blue fits). Occasionally, three exponentials could be fit (Fig. 4C, green fit). Critical taus (τc) separating the two distributions were calculated from IEI distribution fits and used to define the cut-off IEI for defining pHFO bursts. PHFOs occurred in bursts throughout the epileptogenic period, but intra-burst and inter-burst intervals were steady across all post-SE time points (intra-burst interval: 0.5 ± 0.2 s, inter-burst interval: 7.6 ± 2.5 s, p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 4C–E). We assessed pHFO burst length by constructing histograms containing single event and multi-event pHFO burst durations as defined by the τc (Fig. 4F). These distributions could be fit by the sum of a Gaussian and exponential distribution (Fig. 4F). Single pHFO durations contributed almost exclusively to the narrow peak of each histogram, indicating that individual pHFO durations have a log-normal distribution (Fig. 4F, red fit) consistent across time (90 ± 6.5 ms, p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 4G). The second, right-shifted, distribution represents pHFO burst length (with N > 1 pHFOs/burst), and could be fit with an exponential distribution (Fig. 4F). Similar to the other burst parameters measured, the pHFO burst duration remained stable over the four recording periods (1.4 ± 0.4 s, p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 4H).

Spectral dynamics of pHFOs

Sharp-wave ripples (SWR), with a frequency range of 140–250 Hz, of the hippocampal CA3 and CA1 regions reflect synchronous summated EPSCs/IPSCs generated by the interplay of principal cells and inhibitory interneurons 25; 26. In the epileptic hippocampus, pHFOs can possess overlapping frequency components to that of SWRs, ranging from 200 – 600 Hz, but are likely generated by bursts of population spikes 27; 28.

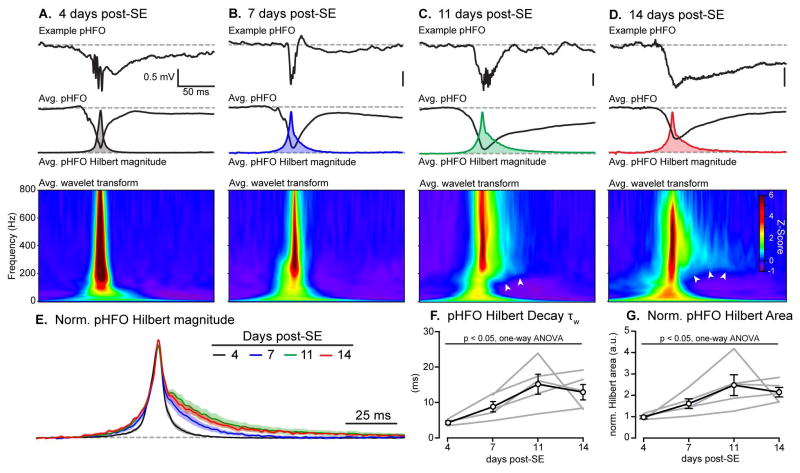

Raw LFP recordings were band-pass filtered from 200–600 Hz and the envelope of the oscillation was calculated using the Hilbert transform (see Methods). The resulting Hilbert magnitude of each pHFO was aligned by its peak, normalized and averaged. The normalized pHFO Hilbert magnitudes were then compared across all four recording days (Fig. 5A–D, colored insets). PHFOs showed a progressive increase in duration from 4 to 14 days post-SE (Fig. 5E), which corresponded to a significant increase in the area of the Hilbert magnitude (p = 0.01, K-W, Fig. 5F). This increase in pHFO duration was due to a prolonged decay of the pHFO Hilbert magnitude, increasing from 4.5 ± 0.5 to 13.1 ± 2.2 ms at 4 to 14 days post-SE, respectively (p = 0.01, K-W, Fig. 5F). This finding was initially at odds with the lack of obvious changes in pHFO duration with burst analysis methods (Fig. 4G). However, pHFO durations reported in Fig 4G were determined by calculating the time between the point at which the 80 ms boxcart smoothed Hilbert magnitude rose above 2.5 × SD and when it dropped back below the same threshold. Consequently, the actual pHFO durations may have been underestimated.

Figure 5. Spectral dynamics of pHFOs evolve during epileptogenesis.

The Hilbert magnitudes of pHFO band-passed (200–600 Hz) events were calculated and aligned by their peaks. All Hilbert magnitudes from a record were then averaged, and the peak of the average trace was normalized to 1. A, The Hilbert magnitude of pHFOs generated 4 days post-SE exhibited sharp onset and fast delay (black trace, Avg. pHFO Hilbert magnitude) with an average weighted decay time constant (τw) of 4.4 ± 0.5 ms. B–D, The pHFO Hilbert magnitude decay τw significantly increased over subsequent recording days (blue, green and red traces), reaching a τw of 13.1 ± 2.2 ms by 14 days post-SE (p = 0.01, one-way ANOVA). A–D, Wavelet transforms, Average Z-score wavelet transforms of pHFOs from 4 to 14 days post-SE reveal sharp pHFOs with broad spectral properties at 4 days post-SE. pHFO spectral properties evolve during epileptogenesis, developing prominent and complex “spectral tails”(white arrows) by 14 days post-SE. E, Overlaid average pHFO Hilbert magnitudes from each recording day demonstrates the significant increase in pHFO decay time constant during epileptogenesis (lines and shaded boundaries are average ± S.E.M.). F & G, Both the decay time constant (F) and Hilbert magnitude area (G) increase significantly from 4 to 14 days post-SE, indicating prolonged pHFO duration during epileptogenesis (p = 0.01, one-way ANOVA).

We next investigated the spectral properties of pHFOs during epileptogenesis using continuous wavelet transform analysis. Average Z-scored wavelet transforms of all detected pHFOs were calculated for all four-time points (Fig. 5A). This analysis revealed that pHFOs at 4 days post-SE have broad frequency components, with peak power at ~200 Hz, and terminated abruptly within 25 ms (Fig. 5A, Avg. wavelet transform). As the latent period progressed, the peak frequency rose to 400–450 Hz and the spectral dynamics of pHFOs appeared to spread out, resulting in a prominent spectral tail with temporally decaying frequency components by 14 days post-SE (Fig. 5A – D, Avg. wavelet transform, arrows).

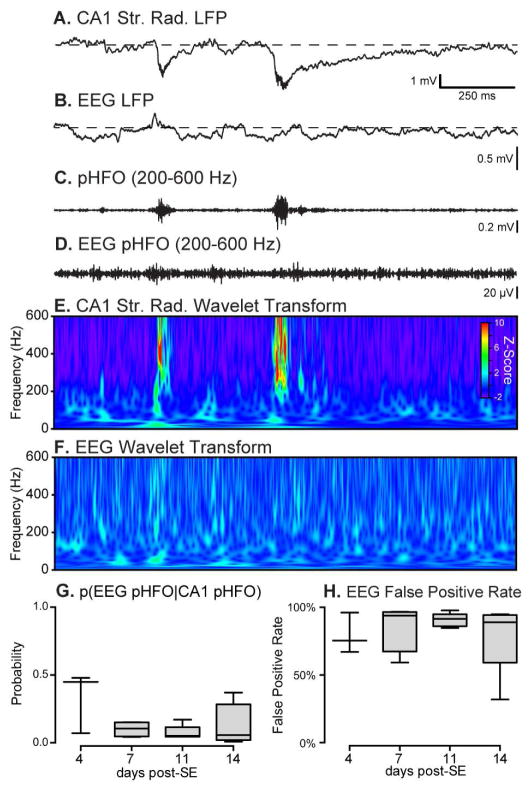

Dural EEGs are unreliable for pHFO monitoring

Since pHFOs are candidate biomarkers of epileptogenesis 27; 29; 30, we sought to determine if hippocampal pHFOs could be reliably recorded with dural EEG recordings, a potentially less invasive way of monitoring epileptogenesis. In simultaneous CA1 LFP and dural EEG recordings we found no reliable EEG characteristic that correlated with hippocampal pHFOs (Fig. 6A–F). The EEG recordings were band-pass filtered in the pHFO range (200–600 Hz) and the probability of detecting an EEG pHFO given the known time points of hippocampal pHFOs was calculated (p(EEG pHFO|CA1 pHFO), Figure 6G). The probability of detecting a corresponding EEG pHFO given the known time points of CA1 pHFOs was very low: 0.14 ± 0.07 (Fig. 6G). We also compared the probability of finding a CA1 pHFO given the detection of a putative pHFO on the dural EEG and found this method to produce very high false positive rates across all time points; average false-positive rate: 84 ± 8% (Fig. 6H). Consequently, in the absence of any reliable dural EEG correlates of hippocampal pHFOs, monitoring epileptogenesis without depth electrodes in the temporal lobe is highly unrealistic.

Figure 6. Dural EEG is unreliable for detecting deep temporal lobe pHFOs.

A & B, Simultaneous CA1 str. radiatum LFP (A) and dural EEG (B) recordings found no unique EEG LFP marker that corresponded with hippocampal pHFOs (arrows). C & D, band passed traces of A & B (200–600 Hz) reveal prominent high-frequency components in the hippocampal LFP but no noticeable events in the dural EEG record. E & F, Wavelet transforms of DG LFP and dural EEG showed prominent high frequency spectral components in the hippocampal LFP but no significant changes in EEG wavelet transform. G, The probability of detecting a pHFO on the EEG recording given the known time points of hippocampal pHFOs was very low throughout epileptogenesis. H, Detecting putative pHFOs on the dural EEG and comparing them to the time points of known hippocampal pHFOs showed a high false positive rate across all recorded time points.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the temporal and spectral properties of pHFOs in the hippocampus during epileptogenesis in a suprahippocampal KA mouse model of TLE. We found that pHFOs are generated as early as 4 days post-SE and exhibit a quantitative evolution during the epileptogenic period. DC LFP recordings reveal that pHFOs ride on transient LFP deflections, with decay time constants that become more prolonged over time. The duration of pHFOs, measured by the Hilbert magnitude of the band-passed (200–600 Hz) recording, also increases over time. This finding was supported by overt changes in the time-frequency properties of pHFOs using continuous wavelet transform analysis. Finally, although pHFOs were prominent in the hippocampus, dural EEG recordings could not reliably detect the hippocampal events.

Progressive nature of pHFOs during epileptogenesis

Our analysis of the spectral-temporal properties of pHFOs reveals that pHFOs not only predict an epilepsy phenotype 16, but they evolve in a consistent manner during epileptogenesis. PHFOs ride on top of LFP deflections, exhibit sharp onset, decay and possess broad spectral components as early as 4 days post-SE. As epileptogenesis progresses, the LFP deflections become more prolonged, with their decay time constants increasing by an order of magnitude, but no increase in amplitude. Moreover, the durations of pHFO Hilbert magnitude decays nearly double by 14 days post-SE. Wavelet analysis identified that peak pHFO frequency also increases and prominent “spectral tails” emerge as the epileptogenesis progresses.

The evolution of pHFOs described in this study is consistent with the current model of epilepsy as a progressive disorder. Studies utilizing excitotoxins, stimulation, or genetic models of epilepsy have all provided strong evidence that epilepsy is a progressive degenerative disorder 31. Our findings that pHFOs, perhaps the earliest known electrophysiological markers of epilepsy, are also progressive in nature is consistent with this current understanding of epilepsy.

PHFOs have been the focus of heavy investigation since they were first described in rodent models and human TLE patients, and are now candidate biomarkers for diagnosing and monitoring epilepsy. Initial reports describing pHFOs demonstrated that the latency to the first pHFO and the number of pHFOs are predictive of the latent period duration and the number of daily seizures during chronic epilepsy 16; 32. Further anatomical evidence from rat models and human TLE patients revealed that pHFOs are more prominent in ictogenic hippocampal regions and regions with accumulated pathological connectivity, such as mossy fiber sprouting in the dentate gyrus 3; 12; 16. Structural MRI studies in TLE patients indicate a negative correlation between pHFO prevalence and overall hippocampal volume, and high-resolution 3D MRI surface mapping have shown that pHFOs are far more likely to be generated in regions of local hippocampal atrophy 33; 34. Finally, surgical removal of pHFO-generating regions of the hippocampus is often successful at mitigating seizures in TLE patients 14; 35; 36.

Mechanisms of pHFO evolution

We find that the pHFO duration and spectral properties show the greatest degree of progression during epileptogenesis. Although the exact mechanisms of pHFO generation in TLE are still under investigation 36; 37, it is clear that they emerge from different network level phenomena than physiological HFOs such as SWRs. The latter are LFP oscillations between 100–200 Hz most prominent in the pyramidal cell layer of CA3 and CA1 regions and are generated by synchronous EPSCs and IPSCs involving perisomatically innervating interneurons 25; 26. In contrast, simultaneous LFP and single cell recordings from dentate gyrus granule cells 38 and CA3 pyramidal neurons 39 have revealed that pHFOs reflect discharges of neuron ensembles and the spectral dynamics of pHFOs emerge from both in-phase and out-of-phase bursting of principal neurons 24. In-phase bursts generate lower frequency pure pHFOs whereas out-of-phase bursting generates oscillation harmonics and pHFOs with high frequency spectral properties. In vitro studies in an acute model of pHFOs found that low extracellular [Ca2+] dramatically reduced the efficacy of perisomatic GABAergic inhibition and was sufficient to convert normal SWRs to pHFOs 40. Furthermore, buffering extracellular [Ca2+] in vivo in epileptic rats modulated the spectral properties of spontaneous pHFOs. In our study, spontaneously generated pHFOs recorded 4 days post-SE exhibited short durations with peak spectral power at approximately 200 Hz. By 14 days post-SE, pHFO durations increased and the peak spectral frequency rose 400–450 Hz (Fig. 5A–D). Therefore, it is possible that the spectral evolution observed in this study reflects the evolution from in- to out-of-phase bursts during epileptogenesis. Given the strong association of pHFOs with anatomical and physiological manifestations of epilepsy, it is possible that the evolution of pHFOs observed in this study reflects the progression of the epileptogenic processes. Consequently, quantitative assessment of pHFOs may be useful for characterizing the severity of epileptic phenotypes and possibly the efficacy of clinical interventions.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

pHFOs (200–600 Hz) were recorded in the hippocampi of awake head-fixed mice 4–14 days after suprahippocampal KA-induced SE.

Two-thirds of the pHFOs were DG-only, the rest could be observed both in the DG and CA1, but could not be recorded with dural electrodes.

The pHFOs occurred in bursts with a random number of events per burst.

The pHFOs showed characteristic temporal and spectral evolution indicating a progression of network alterations during epileptogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health grants 5T32NS058280 to RTJ, R01NS075429 to IM, and the Coelho Endowment to IM.

This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health as follows: 5T32NS058280 to R.T.J., and R01NS075429 and the Coelho Endowment to I.M. We would like to thank Dr. Christian Steinhäuser (Uniklinik Bonn) for his suggestions on the use of the suprahippocampal KA mouse model of TLE, Dr. Sotiris C. Masmanidis (Dept. Neurobiology, UCLA) for help with the use of the 64-channel silicon probes and the Labview software, all members of the ModyLab for stimulating discussions, R. Main Lazaro for animal care, and Albert Barth Sr. for the C++ ball tracking program.

Abbreviations

- TLE

temporal lobe epilepsy

- HS

hippocampal sclerosis

- KA

kainic acid

- HFOs

high-frequency oscillations

- DG

dentate gyrus

- pHFOs

pathological high-frequency oscillations

- s.c

subcutaneous

- i.p

intraperitoneal

Footnotes

Author Contributions: RTJ, AMB, and IM designed experiments. RTJ, AMB, and LDO did the preparation and collected data, and RTJ, AMB, and IM analyzed data. RTJ and IM wrote the manuscript, and IM supervised the research.

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors has any conflict of interest. We have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and declare that our report is consistent with those guidelines.

References

- 1.Hesdorffer DC, Logroscino G, Cascino G, et al. Risk of unprovoked seizure after acute symptomatic seizure: effect of status epilepticus. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:908–912. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.French JA, Williamson PD, Thadani VM, et al. Characteristics of medial temporal lobe epilepsy: I. Results of history and physical examination. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:774–780. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bragin A, Wilson CL, Engel J. Chronic epileptogenesis requires development of a network of pathologically interconnected neuron clusters: a hypothesis. Epilepsia. 2000;41 (Suppl 6):S144–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb01573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engel J. Clinical evidence for the progressive nature of epilepsy. Epilepsy Research Suppl. 1996;12:9–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudek FE, Staley KJ. In: The Time Course and Circuit Mechanisms of Acquired Epileptogenesis. Noebels JL, Avoli M, Rogawski MA, et al., editors. Jasper’s Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies; Bethesda (MD): 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams PA, White AM, Clark S, et al. Development of spontaneous recurrent seizures after kainate-induced status epilepticus. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:2103–2112. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0980-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sloviter RS, Bumanglag AV. Defining “epileptogenesis” and identifying “antiepileptogenic targets” in animal models of acquired temporal lobe epilepsy is not as simple as it might seem. Neuropharmacology. 2013;69:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penfield W. Introduction. Epilepsia. 1961;2:109–110. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg EM, Coulter DA. Mechanisms of epileptogenesis: a convergence on neural circuit dysfunction. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14:337–349. doi: 10.1038/nrn3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bragin A, Engel J, Wilson CL, et al. Hippocampal and entorhinal cortex high-frequency oscillations (100–500 Hz) in human epileptic brain and in kainic acid-treated rats with chronic seizures. Epilepsia. 1999;40:127–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb02065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bragin A, Engel J, Wilson CL, et al. Electrophysiologic analysis of a chronic seizure model after unilateral hippocampal KA injection. Epilepsia. 1999;40:1210–1221. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bragin A, Mody I, Wilson CL, et al. Local generation of fast ripples in epileptic brain. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:2012–2021. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-02012.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staba RJ, Wilson CL, Bragin A, et al. High-frequency oscillations recorded in human medial temporal lobe during sleep. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:108–115. doi: 10.1002/ana.20164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs J, LeVan P, Chander R, et al. Interictal high-frequency oscillations (80–500 Hz) are an indicator of seizure onset areas independent of spikes in the human epileptic brain. Epilepsia. 2008;49:1893–1907. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogren JA, Bragin A, Wilson CL, et al. Three-dimensional hippocampal atrophy maps distinguish two common temporal lobe seizure-onset patterns. Epilepsia. 2009;50:1361–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bragin A, Wilson CL, Engel J. Spatial stability over time of brain areas generating fast ripples in the epileptic rat. Epilepsia. 2003;44:1233–1237. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.18503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bedner P, Dupper A, Huttmann K, et al. Astrocyte uncoupling as a cause of human temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2015 doi: 10.1093/brain/awv067. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volz F, Bock HH, Gierthmuehlen M, et al. Stereologic estimation of hippocampal GluR2/3- and calretinin-immunoreactive hilar neurons (presumptive mossy cells) in two mouse models of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2011;52:1579–1589. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du J, Blanche TJ, Harrison RR, et al. Multiplexed, high density electrophysiology with nanofabricated neural probes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chrobak JJ, Buzsaki G. High-frequency oscillations in the output networks of the hippocampal-entorhinal axis of the freely behaving rat. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:3056–3066. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-09-03056.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McAuliffe JJ, Bronson SL, Hester MS, et al. Altered patterning of dentate granule cell mossy fiber inputs onto CA3 pyramidal cells in limbic epilepsy. Hippocampus. 2011;21:93–107. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Queiroz CM, Gorter JA, Lopes da Silva FH, et al. Dynamics of evoked local field potentials in the hippocampus of epileptic rats with spontaneous seizures. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2009;101:1588–1597. doi: 10.1152/jn.90770.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bragin A, Wilson CL, Engel J. Voltage depth profiles of high-frequency oscillations after kainic acid-induced status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2007;48 (Suppl 5):35–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ibarz JM, Foffani G, Cid E, et al. Emergent dynamics of fast ripples in the epileptic hippocampus. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:16249–16261. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3357-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buzsaki G, Horvath Z, Urioste R, et al. High-frequency network oscillation in the hippocampus. Science. 1992;256:1025–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.1589772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gulyas AI, Freund TT. Generation of physiological and pathological high frequency oscillations: the role of perisomatic inhibition in sharp-wave ripple and interictal spike generation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2014;31C:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engel J, Bragin A, Staba RJ, et al. High-frequency oscillations: what is normal and what is not? Epilepsia. 2009;50:598–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jefferys JGR, Menendez de la Prida LM, Wendling F, et al. Mechanisms of physiological and epileptic HFO generation. Progress in Neurobiology. 2012;98:250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engel J, Pitkanen A, Loeb JA, et al. Epilepsy biomarkers. Epilepsia. 2013;54 (Suppl 4):61–69. doi: 10.1111/epi.12299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zijlmans M, Jiruska P, Zelmann R, et al. High-frequency oscillations as a new biomarker in epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:169–178. doi: 10.1002/ana.22548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pitkanen A, Sutula TP. Is epilepsy a progressive disorder? Prospects for new therapeutic approaches in temporal-lobe epilepsy. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bragin A, Wilson CL, Almajano J, et al. High-frequency oscillations after status epilepticus: epileptogenesis and seizure genesis. Epilepsia. 2004;45:1017–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.17004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogren JA, Wilson CL, Bragin A, et al. Three-dimensional surface maps link local atrophy and fast ripples in human epileptic hippocampus. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:783–791. doi: 10.1002/ana.21703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Staba RJ, Frighetto L, Behnke EJ, et al. Increased fast ripple to ripple ratios correlate with reduced hippocampal volumes and neuron loss in temporal lobe epilepsy patients. Epilepsia. 2007;48:2130–2138. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akiyama T, Otsubo H, Ochi A, et al. Focal cortical high-frequency oscillations trigger epileptic spasms: confirmation by digital video subdural EEG. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2005;116:2819–2825. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobs J, Staba RJ, Asano E, et al. High-frequency oscillations (HFOs) in clinical epilepsy. Progress in Neurobiology. 2012;98:302–315. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menendez de la Prida LM, Trevelyan AJ. Cellular mechanisms of high frequency oscillations in epilepsy: on the diverse sources of pathological activities. Epilepsy Research. 2011;97:308–317. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bragin A, Benassi SK, Kheiri F, et al. Further evidence that pathologic high-frequency oscillations are bursts of population spikes derived from recordings of identified cells in dentate gyrus. Epilepsia. 2011;52:45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foffani G, Uzcategui YG, Gal B, et al. Reduced spike-timing reliability correlates with the emergence of fast ripples in the rat epileptic hippocampus. Neuron. 2007;55:930–941. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aivar P, Valero M, Bellistri E, et al. Extracellular calcium controls the expression of two different forms of ripple-like hippocampal oscillations. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34:2989–3004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2826-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.