Abstract

AIM: To investigate the co-incidence of apoptosis, autophagy, and unfolded protein response (UPR) in hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV) infected hepatocytes.

METHODS: We performed immunofluorescence confocal microscopy on 10 liver biopsies from HBV and HCV patients and tissue microarrays of HBV positive liver samples. We used specific antibodies for LC3β, cleaved caspase-3, BIP (GRP78), and XBP1 to detect autophagy, apoptosis and UPR, respectively. Anti-HCV NS3 and anti-HBs antibodies were also used to confirm infection. We performed triple blind counting of events to determine the co-incidence of autophagy (LC3β punctuate), apoptosis (cleaved caspase-3), and unfolded protein response (GRP78) with HBV and HCV infection in hepatocytes. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software for Windows (Version 16 SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States). P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with Mann-Whitney test to compare incidence rates for autophagy, apoptosis, and UPR in HBV- and HCV-infected cells and adjacent non-infected cells.

RESULTS: Our results showed that infection of hepatocytes with either HBV and HCV induces significant increase (P < 0.001) in apoptosis (cleavage of caspase-3), autophagy (LC3β punctate), and UPR (increase in GRP78 expression) in the HCV- and HBV-infected cells, as compared to non-infected cells of the same biopsy sections. Our tissue microarray immunohistochemical expression analysis of LC3β in HBVNeg and HBVPos revealed that majority of HBV-infected hepatocytes display strong positive staining for LC3β. Interestingly, although XBP splicing in HBV-infected cells was significantly higher (P < 0.05), our analyses show a slight increase of XBP splicing was in HCV-infected cells (P > 0.05). Furthermore, our evaluation of patients with HBV and HCV infection based on stage and grade of the liver diseases revealed no correlation between these pathological findings and induction of apoptosis, autophagy, and UPR.

CONCLUSION: The results of this study indicate that HCV and HBV infection activates apoptosis, autophagy and UPR, but slightly differently by each virus. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the interconnections between these pathways in relation to pathology of HCV and HBV in the liver tissue.

Keywords: Cell fate, Cell death, Hepatocyte, Viral infection, Endoplasmic reticulum stress

Core tip: For the first time, the current study has addressed the co-incidence of apoptosis, autophagy, and unfolded protein response in the liver tissue of hepatitis B and hepatitis C (HBV, and HCV) infected patients. The results showed that all of these events are activated at the same time by HBV and HCV infection in the liver. All of these pathways probably are involved in replication and pathogenesis of HBV and HCV infection; therefore their modulation would probably be beneficial for new therapeutic approaches in these diseases.

INTRODUCTION

The liver is the primary organ infected by, and in which both hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) replicate. HBV and HCV are structurally unrelated and responsible for infection of huge numbers of individuals in the world.

It has been reported that around 2 billion people are infected with HBV, and more than 350 million are chronic carriers according to clinical definitions that identify individuals who have continuous viral and subviral particles in their blood for more than six months[1,2]. Several studies have determined that HBV infection in adulthood might lead to a carrier stage in about 5%-10% of infected individuals. In addition, in up to 30% of these individuals hepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and finally hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) can develop and it is usually considered a progressive chronic liver disease (CLD)[3]. Several groups have investigated the risk of HCC development in different populations and shown that HCC development can be increased up to 100-fold in carrier infected individuals compared with uninfected individuals, which depends on the population and different markers. The risk of developing HCC among carriers with CLD ranges from 10-fold to 100-fold greater compared to uninfected people[2,4]. Approximately 85% of acute HCV infection leads to a chronic situation and 50% of individuals who suffer from HCV chronic infections (about 170 million worldwide) can develop CLD. Approximately 5%-20% of this population can progress to liver cirrhosis in 5-20 years after their infection, and 1%-2% of these patients will probably develop HCC per year[3]. It is strongly believed that this can be considered one of the closest relationships between an environmental agent and a cancer that has so far been identified[3].

Autophagy is a tightly regulated catabolic process, which is essential in many cellular events including development, differentiation, survival, and homeostasis[5-7]. In the past few years, many investigators have focused on the involvement of autophagy in different human diseases and many aspects of this relationship have been described[8-10]. Autophagy is usually considered a very important step for numerous virus life cycles[11], including HBV and HCV[12].

Apoptosis is programmed cell death initiated via two different pathways (1) extrinsic which is activated by ligation of death receptors; and (2) intrinsic which is activated by mitochondrial death-related proteins. These two distinct pathways crosstalk and potentiate each other to ultimately activate the caspase cascade and facilitate controlled proteolysis of cellular components[13-15].

Synthesized and secretory proteins are correctly folded and assembled in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)[16]. During cellular stress, the ER loses its capacity to correct protein folding which results in the accumulation of unfolded and misfolded proteins. Following this, the unfolded protein response (UPR) targets the degradation of the accumulated proteins in the ER, inhibits global protein translation and also activates the transcription of genes that increase the protein folding capacity of the ER including lectins, chaperones, and calcium pumps[17]. Three ER membrane sensors mediate signals from the ER upon activation of the UPR including activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), and protein kinase RNA (PKR)-like ER-localized kinase (PERK)[16]. Each of these molecules activates independently distinct signaling pathways to provide an integrated response to ER stress[18]. Unfolded and misfolded proteins in the ER disrupt binding of the binding immunoglobulin protein (BIP)/glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) with ER stress sensors, leading to their activation. PERK phosphorylates eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) which results in a decrease in mRNA translation with concurrent translation increase of several mRNAs like activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) and the CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) (ATF4 downstream target)[16].

Several previous investigations have shown that HBV[19-24] and HCV[25-27] infection can modulate apoptosis, autophagy, and UPR in different in vitro and non-human in vivo models. However, most of these studies did not use human samples and also have not simultaneously investigated apoptosis, autophagy, and UPR in the same infected tissue or organ. To address these gaps, we used tissue microarray, and fluorescence immunohistochemistry (IHC) in the present study to evaluate apoptosis, autophagy and UPR in human biopsy samples from patients who were infected with HBV or HCV. This study, for the first time, provides an evaluation of these events at the same time in HBV and HCV liver biopsies of infected patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study for immunoflourescence or IHC, or both: LC3β antibody was obtained from Proteintech (18725-1-AP, Chicago, IL, United States). Antibody for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) was obtained from Novus Biologicals (NBP1-22568, Littleton, CO, United States). Cleaved caspase-3 (Asp175) antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (#9661, MA, United States). Anti-Hepatitis C virus NS3 (ab49486), anti-BIP (GRP78) (ab21685) and anti-XBP1 (ab37152) antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, United States). Biotin conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Inc. (West Grove, PA, United States). VECTASTAIN Peroxidase ABC kit was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, United States). Fluorescent-conjugated (Alexa Fluor 488 and 546) secondary antibodies were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, United States). Type B hepatitis and normal liver tissue array (IC03001) was purchased from United States BioMax (Rockville, MD, United States).

Ethical protocol

This retrospective study was approved by local research ethics committee of Health policy research Center (Protocol number HP-101-91). All patients were informed about the study and gave verbal informed consent prior to enrollment.

Selection criteria for HBV and HCV patients

HBV- and HCV-infected individuals (10 in each group) were diagnosed and selected based on the following criteria from the patients who had been referred to Namazi Hospital (Shiraz, Iran): (1) HBV-infected patients: Hepatitis virus surface antigen positive and HBV DNA > 2000 IU/mL in the serum; and (2) HCV-infected patients: HCV antibody positive, which was confirmed by detecting HCV RNA in the serum.

All cases had abnormal levels of liver enzymes including alanine transaminase; 2 × the upper limit of normal range (Normal Range is 7-56 IU/L) in two measurements that were performed three months apart. In all cases other diagnoses were ruled out with appropriate work up and no case had mixed cause of liver function abnormality in this series. DNA was extracted using Qiagen kit (Qiagen, Hiden, Germany), as per manufacturer’s instructions. HBV and HCV genome copy numbers were measured using Qiagen kit (Germany). Patients with other causes of chronic liver disease such as Wilson’s hemochromatosis, drug induced liver disease, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, or alcoholic liver diseases were excluded. Patients were also excluded if pregnant, or if presented with comorbid conditions including diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, or chronic kidney disease.

Liver biopsy and sample preparation

Biopsy of the liver was performed by the radiologist under the guide of ultrasound or computerized tomography (CT) scan using Tru-cut® needles (standard biopsy needle). Biopsies were fixed in formalin, and then processed as routine pathology specimens.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded liver tissues were used for histology and IHC. Briefly, paraffin sections of 4 μm thickness were prepared, deparaffinized, rehydrated and used for staining. Following unmasking of antigens using Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval and citrate buffer (0.1 mol/L citric acid, 0.1 mol/L sodium citrate, pH 6.0) in a Coplin Jar for 30 min, IHC was performed by means of detecting antigens with corresponding primary antibodies followed by biotinylated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs) and an avidin-biotin peroxidase complex technique using ABC kit. The slides were then counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Sigma, H9627), dehydrated and mounted with Permount (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, ON, Canada). For Immunofluorescence staining, after primary antibody incubation, sections were covered with fluorescent-conjugated (Alexa Fluor 488 and 546) secondary antibodies followed by nuclear staining using ProLong® Gold Antifade Mountant with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole DAPI (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, United States).

As a negative control, sections were processed as above but addition of primary antibody was omitted. Images were captured using a Leica CTRMIC 6000 confocal microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu C910013 spinning disc camera (Leica Microsystems, Inc., Concord, ON, Canada). Laser intensity and detector sensitivity settings remained constant for all image acquisitions within each experiment. Images were later analyzed with Volocity software (Perkin-Elmer, Woodbridge, ON, Canada).

Liver tissue microarray and scoring

IHC analysis was performed on commercially available tissue microarray (TMA) (cat. No. IC03001; Biomax Inc., Rockville, MD, United States) consisting of 30 cases of normal liver tissue and 10 cases of HBV-induced hepatitis. For evaluation of IHC staining, semi-quantitative scoring (H-scores) was used to assess positive staining for LC3β protein expression in TMAs according to the method described previously[28]. The H-score was calculated by a semi-quantitative assessment of both staining intensity (scale 0-3) and the percentage of positive cells (0%-100%), which, when multiplied, generated a score ranging from 0 to 300. The intensity score was made on the basis of the average intensity of staining where 0 = negative, 1 = weak, 2 = intermediate and 3 = strong. Statistical analysis was carried out on the H-score data obtained. Scoring of the sections was performed blindly by three independent individuals.

Classification of HBV and HCV patients based on the liver disease stage and grade

HBV and HCV patient liver biopsies were carefully assessed by two pathologists and the stage and grade of their liver disease were classified based on the following definitions:

Grade (necroinflammation grade): 0 = none, 1-6 = mild, 7-12 = moderate, 13-18 = severe; Stage (Ishak Fibrosis Score): 0 = No fibrosis, 1-2 = Fibrous expansion of some and most portal areas (+/-) short fibrous septa, 3-4 = Fibrous expansion of most portal areas with occasional portal to portal (P-P) bridging and Fibrous expansion of portal areas with marked bridging (P-P) as well as portal to central (P-C), 5-6 = Marked bridging (P-P and/or P-C), with occasional nodules (incomplete cirrhosis), and Cirrhosis, probable or definite. The results of HBV and HCV patient classifications are shown in Table 1 (stage) and Table 2 (grade).

Table 1.

Stage of liver disease in hepatitis B and C virus infected patients

| Stage | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| HBV (n) | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| HCV (n) | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

Table 2.

Grade of liver disease in hepatitis B and C virus infected patients

| Grade | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| HBV (n) | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| HCV (n) | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software for Windows (Version 16 SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States). P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with Mann-Whitney test for comparing autophagy marker (punctate LC3β), apoptosis marker (cleaved caspase-3), and UPR marker (BIP) between HBV- and HCV-infected cells and adjacent non-infected cells. Statistical analyses were performed with Kruskal-Wallis test for relation of stage (ordinal variable) and grade (ordinal variable) liver biopsies of HBV and HCV patients with autophagy marker (punctate LC3β), apoptosis marker (cleaved caspase-3), and UPR marker (BIP). Because of our small sample size, we used the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. It is noteworthy to mention that Kruskal-Wallis test is equivalent nonparametric test of “one-way analysis of variance”.

RESULTS

HBV and HCV infection induces autophagy in human liver tissue

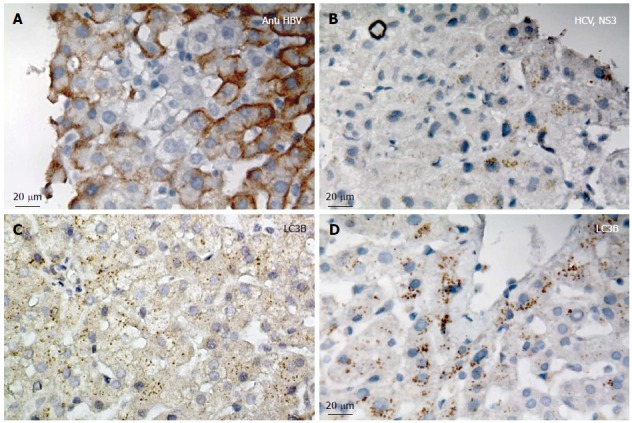

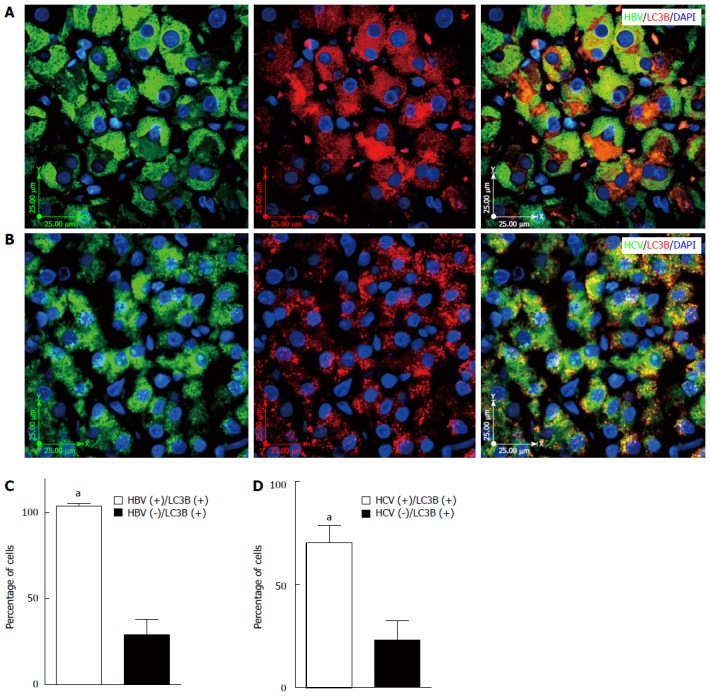

IHC analyses confirmed HBV and HCV infection in different liver tissue samples (Figure 1A and B). LC3β expression was later investigated in different HBV- and HCV-infected liver tissues and LC3β expression was confirmed in all samples (Figure 1C and D). It has been previously shown that lipidated LC3β serves as a reliable marker of autophagy in ICC and IHC[5,29-31]. Because the previous immunochemistry analyses were meant to primarily confirm infection status and globally explore LC3β expression, we also used fluorescent IHC to directly identify autophagy in the liver biopsy cells from HBV and HCV positive patients (Figure 2A and B). Our results show accumulation of autophagosomes in HBV- (Figure 2A) and HCV- (Figure 2B) infected hepatocytes as determined by significantly higher number of LC3β-positive puncta in both HBV- (Figure 2C) and HCV- (Figure 2D) infected cells compared to adjacent non-infected hepatocytes (P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Confirmation of hepatitis B and C virus infection and LC3β expression in liver tissues. A: Immunohistochemistry (IHC) confirms hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in the liver tissue; the image is representative of IHC for HBV infection in all patients; B: IHC confirms hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (Anti NS3 HCV) in the liver tissue; the image is representative of IHC for HCV infection in all patients; C: IHC confirms LC3β expression in HBV infected liver tissue; the image is representative of IHC for all patients; D: IHC confirms LC3β expression in HCV infected liver tissue; the image is representative of IHC for all patients.

Figure 2.

Hepatitis B and C virus infection induces autophagy in liver tissues. A: Fluorescent immunohistochemistry (IHC) confirms co-localization of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and punctate LC3β in the HBV-infected liver tissue; the image is representative of fluorescence IHC for all patients; B: Fluorescencent IHC confirms co-localization of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and punctate LC3β in the HCV infected liver tissue; the image is representative of fluorescence IHC for all patients; C: HBV infection significantly (aP < 0.001 vs HBV-) induces autophagy in the infected hepatocytes compared to non-infected adjacent cells. The graph shows results of the event (HBV infection and punctuated LC3β) in at least 50 cells counted in four different microscopic fields of view from each patient’s sample. D: HCV infection significantly (aP < 0.001 vs HCV-) induces autophagy in the infected hepatocytes compared to non-infected adjacent cells. The graph shows results of the event (HCV infection and punctuated LC3β) in at least 50 cells counted in four different microscopic fields of view from each patient’s sample.

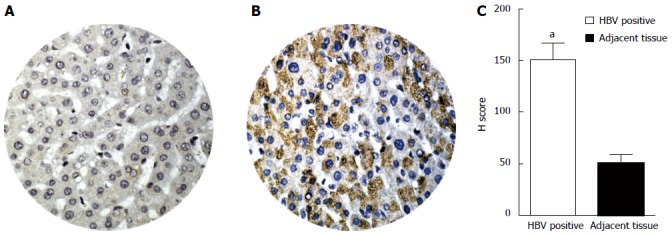

Tissue microarray immunohistochemical profile of LC3β in HBVNeg and HBVPos hepatocytes

Immunostaining for LC3β was performed on the commercially available TMA slide (see Materials and Methods). A total of 40 samples were analyzed. Ten of the samples were type B hepatitis and 30 were normal liver tissue. Normal liver cells, as well as adjacent non-infected cells in the HBV-infected samples, displayed weak LC3β staining (Figure 3A). However, the majority of HBV-infected liver cells exhibit strong positive staining of LC3β (Figure 3B). Evaluation of LC3β protein expression by IHC using H-score showed a significant (P < 0.001) cytoplasmic staining of LC3β compared with the normal liver samples (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Comparison of LC3β expression, determined by immunohistochemistry in HBVPos and HBVNeg liver tissue microarrays. Immunohistochemistry was performed as described in Materials and Methods. H-scores were derived from semi-quantitative assessments of both staining intensity (scale 0-3) and the percentage of positive cells (0%-100%) and, when multiplied, generate a score ranging from 0 to 300. A: Representative image of tissue core from HBVNeg liver showing low expression of LC3β (H-score of 50); B: HBVPos liver tissue showing higher expression of LC3β (H-score of 150); C: The bar graphs show expression levels (H-score) of LC3β in HBVPos and HBVNeg liver tissue microarrays. The bars represent the mean ± SEM. aP < 0.001 vs the normal HBVNeg. HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

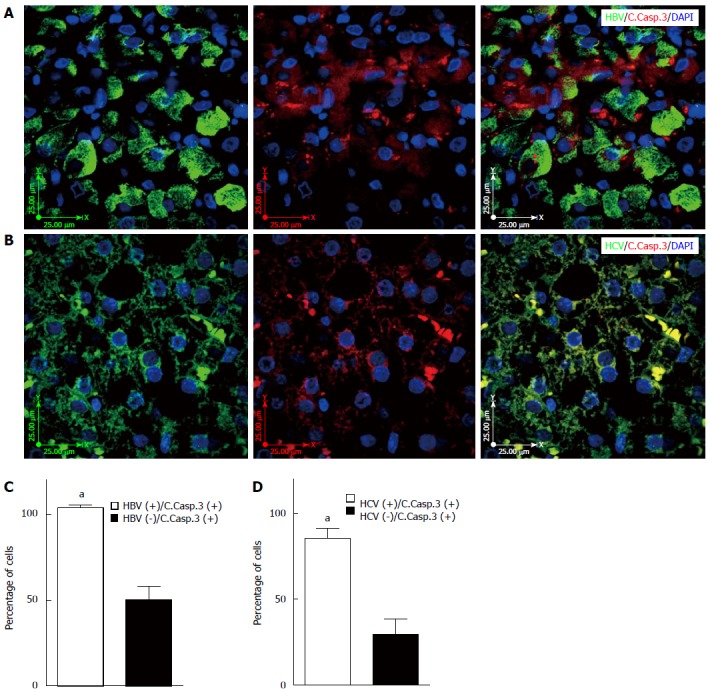

HBV and HCV infection induces apoptosis in human liver tissue

Previous reports have shown that caspase-3 cleavage is one of the most important hallmarks of apoptosis activation in different models[6,32,33]. The results of immunofluorescence staining showed that both HBV and HCV infection induce caspase-3 cleavage in infected hepatocytes (Figure 4A and B). In addition, caspase-3 cleavage was significantly higher in HBV- and HCV-infected cells compared to non-infected adjacent cells (Figure 4C and D) (P < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Hepatitis B and C virus infection induces apoptosis in the infected liver tissue. A: Immunofluorescence double-labeling shows co-localization of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and cleaved caspase-3 in the HBV infected liver tissue; the image is representative of fluorescence immunohistochemistry (IHC) for all patients; B: Immunofluorescence double-staining shows co-localization of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and cleaved caspase-3 in the HCV infected liver tissue; the image is representative of fluorescence IHC for all patients; C: HBV infection significantly (aP < 0.001 vs HBV-) induces apoptosis in the infected hepatocytes compared to non-infected adjacent cells. The graph shows results of the event (HBV infection and cleaved caspase-3) in at least 50 cells counted in four different microscopic fields from each patient’s sample; D: HCV infection significantly (aP < 0.001 vs HCV-) induces apoptosis in the infected hepatocytes compared to non-infected adjacent cells. The graph shows results of the event (HCV infection and cleaved caspase-3) in at least 50 cells counted in four different microscopic fields from each patient’s sample.

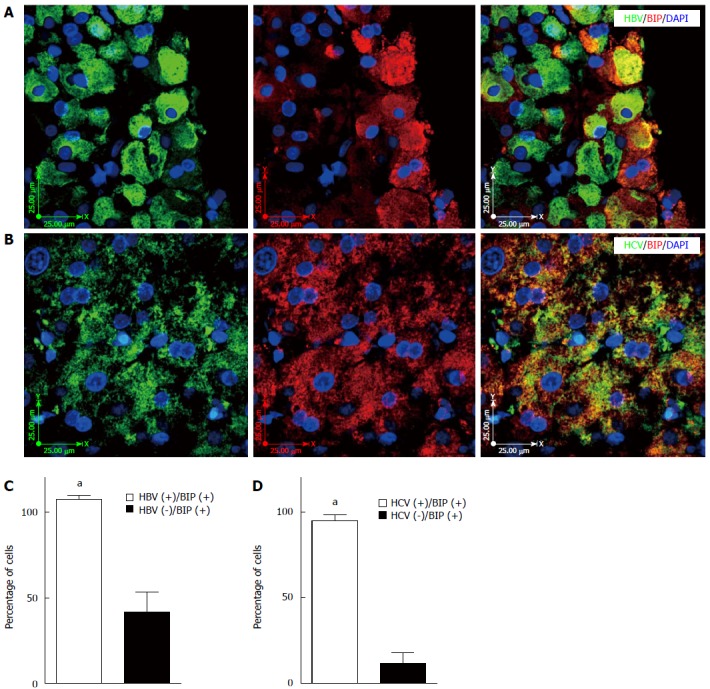

HBV and HCV infection induces UPR in human liver tissue

UPR induces expression of genes encoding proteins, such as BIP, to restore ER homeostasis[29,34]. Therefore, higher expression of BIP is the major biochemical marker of the activation of UPR. Analysis of IHC staining showed significantly higher expression of BIP in HBV (Figure 5A and C) and HCV (Figure 5B and D) infected hepatocytes compared to non-infected adjacent cells (P < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Hepatitis B and C virus infection induces unfolded protein response in the infected liver tissue. A: Fluorescence immunohistochemistry (IHC) confirms co-localization of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and BIP (GRP78) expression in the HBV-infected liver tissue; the image is representative of fluorescence IHC for all patients; B: Fluorescence IHC confirms co-localization of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and BIP (GRP78) expression in the HCV-infected liver tissue; the image is representative of fluorescence IHC for all patients; C: HBV infection significantly (aP < 0.001 vs HBV-) induces UPR in the infected hepatocytes compared to non-infected adjacent cells. The graph shows results of the event,HBV infection and BIP (GRP78) expression in at least 50 cells counted in four different views of fluorescence IHC in each patient’s sample; D: HCV infection significantly (aP < 0.001 vs HCV-) induces UPR in the infected hepatocytes compared to non-infected adjacent cells. The graph shows results of the event (HCV infection and BIP (GRP78) expression) in at least 50 cells counted in four different views of fluorescence IHC in each patient’s sample. UPR: Unfolded protein response.

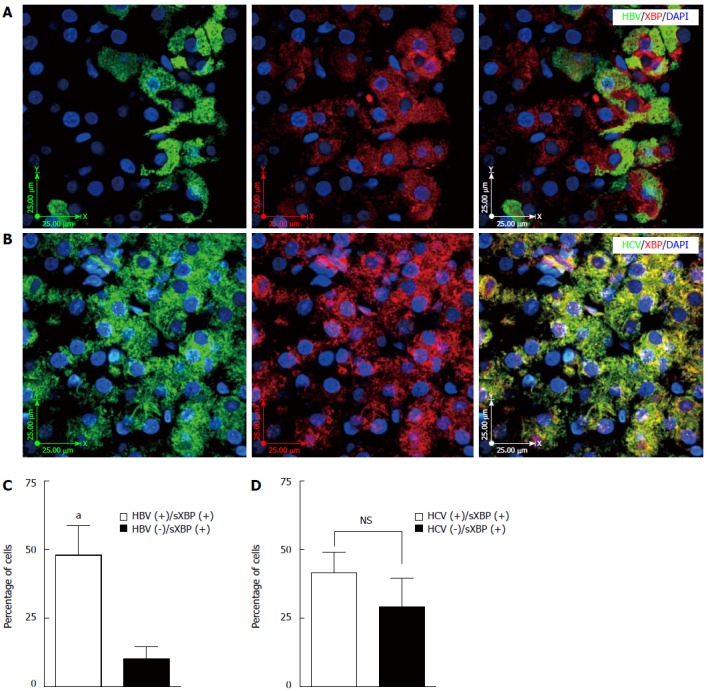

HBV infection induces XBP1 splicing in human liver tissue

IRE1α is a bifunctional enzyme which possesses kinase and RNase activity. One of the primary targets of RNase activity of IRE1α is XBP1, leading to production of spliced XBP1 (sXBP1) during the UPR[13,34]. In our present investigation, we showed that both HBV and HCV infection induced XBP1 expression in infected hepatocytes (Figure 6A and B). Interestingly, HBV infection significantly induced XBP1 splicing (nuclear localized XBP1) compared to adjacent non-infected hepatocytes (Figure 6C) (P < 0.001) while HCV infection increased XBP splicing which is not statistically different compared to non-infected adjacent cells (Figure 6D) (P > 0.05).

Figure 6.

Hepatitis B virus infection induces XBP splicing in the infected liver tissue while hepatitis C virus infection does not induce XBP splicing. A: Fluorescence immunohistochemistry (IHC) confirms co-localization of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and spliced XBP (sXBP) (spliced XBP localized in the nucleus) in the HBV-infected liver tissue; the image is representative of fluorescence IHC for all patients; B: Fluorescence IHC shows that co-localization of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and spliced XBP (sXBP) (spliced XBP localized in the nucleus) is not a dominant event in the HCV-infected liver tissue; the image is representative of fluorescence IHC for all patients; C: HBV infection significantly (aP < 0.001 vs HBV-) induces XBP splicing (spliced XBP localized in the nucleus) in the infected hepatocytes compared to non-infected adjacent cells. The graph shows results of the event [HBV infection and spliced XBP (sXBP) (spliced XBP localized in the nucleus)] in at least 50 cells counted in four different views of fluorescence IHC in each patient’s sample; D: HCV infection does not significantly (P > 0.05) induce XBP splicing in the infected hepatocytes compared to non-infected adjacent cells. The graph shows results of the event [HCV infection and spliced XBP (sXBP) (spliced XBP localized in the nucleus)] in at least 50 cells counted in four different views of fluorescence IHC in each patient’s sample.

Autophagy, apoptosis, and UPR do not correlate with the stage and the grade of liver disease in HBV and HCV patients

Our statistical analysis showed that autophagy, apoptosis, and UPR do not significantly correlate with the stage and the grade of the liver disease in both HBV and HCV patient groups (Tables 1 and 2) (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

In the current study we showed that HBV or HCV infection can significantly induce apoptosis, autophagy, and UPR in infected human patient hepatocytes compared to non-infected adjacent cells. This study importantly represents real clinical sample evaluation of these events in the context of authentic HBV and HCV infection.

HCV infection has a striking tendency towards chronicity, often of significant liver diseases like chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma[35]. Apoptosis (programmed cell death) is a cellular process in which cells systematically kill themselves through activating intracellular death pathways in response to different kinds of stimuli[36]. Although apoptosis has been observed as a crucial mechanism in viral clearance[37], the exact mechanisms of HCV pathogenesis have not yet been fully delineated. There is an accumulating body of evidence that highlights the significant role of hepatocyte apoptosis regulation in HCV pathogenesis[38] and a variety of apoptotic pathways were proposed that might be involved in this mechanism[39]. The HCV core protein alone can greatly affect cellular functions. It can either induce or inhibit the apoptosis process. Apoptosis promotion by the core protein may be the reason for occurrence of hepatitis and liver damage and apoptosis inhibition. On the other hand, core might provide conditions for HCV to establish persistent infection[40].

HBV is also a causative agent of chronic hepatitis and represents one of the major risk factors for development of HCC[41-43]. The hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) has recently garnered much attention regarding its effect on cellular functions, especially apoptosis during HBV infection. Being the smallest protein encoded by HBV genome, HBx is expressed in 70% of patients with HBV-related HCC[44,45], highly conserved in mammalian hepadnaviruses and essential for infection in mammals[46]. HBx has various functions that may participate in HBV pathogenesis[47] and different studies have investigated the role of HBx in multifaceted aspects of apoptosis process. One of the main mechanisms of HBx protein during HBV infection and that contributes to HCC development is its influence on apoptosis. Since the pro-apoptotic functions of HBx were first described[47], a wide range of different studies have evaluated the effect of HBx expression on apoptotic pathway regulation; however, results of such studies are variable. According to studies in multiple cellular contexts, HBx might induce[19,20,47-53], inhibit[54-57] or have no effect[58] on apoptosis.

As previously mentioned, autophagy is often defined as an evolutionarily conserved process that catabolizes intracellular components by delivering them into lysosomes[59-61]. It has been shown that some viruses utilize and induce autophagy in favor of their own replication and survival using their proteins[62-64]. To contribute to different steps of its life cycle like replication, translation, assembly, and lipo-viro-particle release, HCV takes advantage of the autophagic process. However, these effects are partially indirect[65]. Similarly, several studies have been performed aimed at clarifying the involvement of autophagy in establishment of chronic HCV infection[26,66,67] and findings from these studies suggest that autophagy is involved in HCV infection. A subgenomic replicon, corresponding to the HCV NS3-NS5B coding region of HCV genotype 1b, can trigger autophagy[68] which implies autophagy induction via viral nonstructural proteins. In addition, siRNA-targeting ATGs, that inhibit autophagy, abrogates HCV replication[69]. Moreover, HCV infection activates various pattern recognition receptors[70], being able to trigger autophagy[71]. Nevertheless, their exact roles in autophagy induction during HCV infection remains poorly understood.

Some recent studies investigated the interaction between HBV chronic infection and autophagy[72,73]. Autophagy is involved in different stages of HBV development and infection; however, its exact impacts are not fully known. Presumably, autophagy can either increase the replication of HBV DNA or contribute to HBV envelopment[22,74]. Results from electron microscopy, confocal microscopy, and biochemical assays have demonstrated that HBV can enhance autophagy during infection in cell cultures and mouse liver[72]. There is compelling evidence that HBV acts on the early step of phagosome formation and that the degradation rate of autophagic protein is not increased while HBV triggers the formation of early phagosomes[74,75]. Different HBV proteins are involved in the autophagy process. HBx not only is involved in apoptosis induction[19] but also in autophagy process in the course of HBV infection[73]. HBV usurps cellular activities such as autophagy and proliferation in favor of virus replication[22]. Nevertheless, the involved mechanisms for the induction of autophagy and the step of HBV replication affected by autophagy are not completely understood and open to interpretation[72,74].

The UPR has recently been identified as a novel mechanism involved in a wide range of human diseases including viral infections[76,77]. In fact, it has been revealed that a number of viruses utilize UPR to help attenuate anti-viral responses and establishment of infection[78-82]. HCV uses the membranous compartment of the ER as the biogenesis site for its envelope protein and particle assembly[83]. Therefore, there is general agreement on the induction of ER stress by HCV infection which can interfere with the ER function in host cells and upon sensing ER stress, cells activate the UPR signaling pathway[18]. Moreover, there are some well documented data that HCV induces ER stress and UPR in both in vitro and in vivo experimental models[27,84-86]. Virus-induced UPR is demonstrated to trigger apoptosis of the infected hepatocytes and also overwhelming evidence indicates the crucial role of UPR in the HCV replication[68,84,85] and life cycle[27,85-92]. HCV infection apparently activates all three UPR sensors[27,60,84,93]. It was observed in a cell culture system that HCV-induced UPR plays a positive role in RNA replication and efficient propagation of HCV as HCV replication was suppressed when one of three UPR pathways was significantly abrogated[68]. A study by Zheng et al[92] showed that HCV NS4B can activate UPR by induction of XBP1 mRNA splicing and ATF6 cleavage. Our finding shows that there is no significant difference in XBP splicing between HCV-infected and non-infected cells which does not correlate with previous reports that highlighted the role of XBP splicing in HCV infection in hepatocytes. We assume that this difference could be the result of the difference in genetic background of the population study or the lack of enough samples in our study.

Different studies have shown that HBx protein of HBV can trigger UPR. Meanwhile, a major drawback that has prevented us from broadening our in-depth knowledge in a natural infection system has been the lack of a strong and efficient in vitro infectivity model[94]. Cho et al[24] observed that HBx downregulates the cellular ATP level and mitochondrial membrane potential; then ATP reduction induces ER stress. In addition, ATF4, which is a UPR marker, was demonstrated to up-regulate COX2 expression. This kind of UPR induction by HBx might trigger the development of HCC as well as liver inflammation[24]. Moreover, HBx and S proteins both can activate the IRE1/XBP1 branch of the UPR. Li et al[23] demonstrated that the transiently-expressed HBx protein in Hep3B and HepG2 cells caused a high increase (up to 7-fold) in XBP1 promoter activity and also ATF6 cleavage in a dose-dependent manner. This mechanism of HBx in inducing UPR was determined as a potential mechanism, contributing to the replication of HBV in liver cells[23]. Similarly, in another study conducted by Li et al[74], they over-expressed the S protein in Huh7 hepatoma cells and observed the presence of the XBP1 mRNA (both precursor and spliced forms) which suggests the ability of S protein to trigger UPR by the IRE1/XBP1 pathway. XBP1, as a crucial sensor of UPR pathway, is a key protein in the growth and differentiation of hepatocytes as shown by XBP1 knockout mice[95]. It is supposed that HBx might act as a kinase activator that increases the phosphorylation level of the ER stress sensor IRE1, thereby activating the IRE1-XBP1 pathway. On the other hand, HBx is able to interact with the bZIP class of transcription factors and both ATF6 and XBP1 belong to this family so that HBx can activate or co-activate them to enhance trans-activating activities[95]. Furthermore, HBx might be involved in the expression and persistence of HBV since the ATF6 pathway associates with ER chaperone expression and helps the unfolded proteins to refold[91,96]. It should be noted that studies on the UPR at early stages of HBV infection have not yet been addressed and this may be due to the difficulty in investigating HBV infection[97].

In conclusion, our studies confirm previous in vivo and in vitro studies which showed HBV and HCV infection is associated with the induction of apoptosis, autophagy, and UPR in hepatocytes. In the present study, we showed, for the first time, simultaneous induction of apoptosis, autophagy, and UPR after HBV or HCV infection in human liver tissue. Our study highlights the co-incidence of all of these events in the human liver after natural HBV or HCV infection. As apoptosis, autophagy, and UPR are linked together via different regulatory proteins, it will be very important to address which events (apoptosis, autophagy, or UPR) are induced first after HBV or HCV induction. This understanding would be beneficial to design new strategies to control these pathways after HBV or HCV infection to ameliorate the process of liver injury after viral infection. As our study has been done in human samples, these results have great potential impact in HBV- and HCV-infection-initiated liver diseases. Further long term and follow up studies are in process to highlight the effect of these events in the progression of liver diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study is a complementary and Side Project of the PhD thesis of Dr. Payam Peymani (Thesis Number: 92-6907).

COMMENTS

Background

Hepatitis caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has emerged as a major public health problem throughout the world. Dysregulation of apoptosis, autophagy and the unfolded protein response (UPR) has been implicated in a wide spectrum of human diseases including viral infection. These pathways are tightly interconnected and their crosstalk is a key factor for cell-fate determination in response to different stimuli. However, their interplay during HBV and HCV infection remains unclear. In this study the authors investigated induction of autophagy, UPR, and apoptosis in HBV- and HCV-infected human liver tissues to examine the importance of these pathways in HBV- and HCV-induced liver damage. In addition, these studies will pave the way for the development and application of therapeutics that modulate these pathways to affect HBV and HCV replication and the progress of liver damage in patients.

Research frontiers

The authors investigates the importance of apoptosis, autophagy, and UPR in health and diseases. They modulate these pathways to provide new approaches in treatment of different diseases.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The current research showed the co-incidence of apoptosis, autophagy, and UPR in HBV and HCV infected hepatocytes.

Applications

The next step of this research would be to target the modulation of apoptosis, autophagy, UPR in the hepatocytes of HBV/HCV infected patients to prevent the progress of liver damage in these patients.

Peer-review

This is an interesting manuscript about cell fate in hepatocytes after hepatitis B and C virus infection. Also, the manuscript was clearly written and organized.

Footnotes

Supported by University of Manitoba Start-up funds and an award from the Manitoba Medical Service Foundation to Ghavami S; University of Manitoba Start-up Funds to Alizadeh J.

Institutional review board statement: This retrospective study was approved by local research ethics committee of Health policy research Center (Protocol number HP-101-91). All patients were informed about the study and gave verbal informed consent prior to enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data sharing statement: This is an open access work and the researcher can use the data for any further investigations.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: August 30, 2015

First decision: September 29, 2015

Article in press: November 13, 2015

P- Reviewer: Kanda T S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557–2576. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beasley RP, Hwang LY, Lin CC, Chien CS. Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B virus. A prospective study of 22 707 men in Taiwan. Lancet. 1981;2:1129–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90585-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arzumanyan A, Reis HM, Feitelson MA. Pathogenic mechanisms in HBV- and HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:123–135. doi: 10.1038/nrc3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen VT, Law MG, Dore GJ. Hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiological characteristics and disease burden. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:453–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghavami S, Cunnington RH, Gupta S, Yeganeh B, Filomeno KL, Freed DH, Chen S, Klonisch T, Halayko AJ, Ambrose E, et al. Autophagy is a regulator of TGF-β1-induced fibrogenesis in primary human atrial myofibroblasts. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1696. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marzban H, Del Bigio MR, Alizadeh J, Ghavami S, Zachariah RM, Rastegar M. Cellular commitment in the developing cerebellum. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:450. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutierrez MG, Master SS, Singh SB, Taylor GA, Colombo MI, Deretic V. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell. 2004;119:753–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wasik AM, Grabarek J, Pantovic A, Cieślar-Pobuda A, Asgari HR, Bundgaard-Nielsen C, Rafat M, Dixon IM, Ghavami S, Łos MJ. Reprogramming and carcinogenesis--parallels and distinctions. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2014;308:167–203. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800097-7.00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hara T, Nakamura K, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakahara Y, Suzuki-Migishima R, Yokoyama M, Mishima K, Saito I, Okano H, et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Komatsu M, Waguri S, Chiba T, Murata S, Iwata J, Tanida I, Ueno T, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Kominami E, et al. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441:880–884. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanida I, Fukasawa M, Ueno T, Kominami E, Wakita T, Hanada K. Knockdown of autophagy-related gene decreases the production of infectious hepatitis C virus particles. Autophagy. 2009;5:937–945. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.7.9243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alavian SM, Ande SR, Coombs KM, Yeganeh B, Davoodpour P, Hashemi M, Los M, Ghavami S. Virus-triggered autophagy in viral hepatitis - possible novel strategies for drug development. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:821–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghavami S, Yeganeh B, Stelmack GL, Kashani HH, Sharma P, Cunnington R, Rattan S, Bathe K, Klonisch T, Dixon IM, et al. Apoptosis, autophagy and ER stress in mevalonate cascade inhibition-induced cell death of human atrial fibroblasts. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e330. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghavami S, Cunnington RH, Yeganeh B, Davies JJ, Rattan SG, Bathe K, Kavosh M, Los MJ, Freed DH, Klonisch T, et al. Autophagy regulates trans fatty acid-mediated apoptosis in primary cardiac myofibroblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:2274–2286. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qu X, Zou Z, Sun Q, Luby-Phelps K, Cheng P, Hogan RN, Gilpin C, Levine B. Autophagy gene-dependent clearance of apoptotic cells during embryonic development. Cell. 2007;128:931–946. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malhi H, Kaufman RJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in liver disease. J Hepatol. 2011;54:795–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogata M, Hino S, Saito A, Morikawa K, Kondo S, Kanemoto S, Murakami T, Taniguchi M, Tanii I, Yoshinaga K, et al. Autophagy is activated for cell survival after endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:9220–9231. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01453-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chami M, Ferrari D, Nicotera P, Paterlini-Bréchot P, Rizzuto R. Caspase-dependent alterations of Ca2+ signaling in the induction of apoptosis by hepatitis B virus X protein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31745–31755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang X, Liu Y, Zhang Q, Gao L, Han L, Ma C, Zhang L, Chen YH, Sun W. Hepatitis B virus sensitizes hepatocytes to TRAIL-induced apoptosis through Bax. J Immunol. 2007;178:503–510. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sir D, Kuo CF, Tian Y, Liu HM, Huang EJ, Jung JU, Machida K, Ou JH. Replication of hepatitis C virus RNA on autophagosomal membranes. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:18036–18043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.320085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang SW, Ducroux A, Jeang KT, Neuveut C. Impact of cellular autophagy on viruses: Insights from hepatitis B virus and human retroviruses. J Biomed Sci. 2012;19:92. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-19-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li B, Gao B, Ye L, Han X, Wang W, Kong L, Fang X, Zeng Y, Zheng H, Li S, et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) activates ATF6 and IRE1-XBP1 pathways of unfolded protein response. Virus Res. 2007;124:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho HK, Cheong KJ, Kim HY, Cheong J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by hepatitis B virus X protein enhances cyclo-oxygenase 2 expression via activating transcription factor 4. Biochem J. 2011;435:431–439. doi: 10.1042/BJ20102071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honda M, Kaneko S, Shimazaki T, Matsushita E, Kobayashi K, Ping LH, Zhang HC, Lemon SM. Hepatitis C virus core protein induces apoptosis and impairs cell-cycle regulation in stably transformed Chinese hamster ovary cells. Hepatology. 2000;31:1351–1359. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.7985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mack HI, Munger K. Modulation of autophagy-like processes by tumor viruses. Cells. 2012;1:204–247. doi: 10.3390/cells1030204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merquiol E, Uzi D, Mueller T, Goldenberg D, Nahmias Y, Xavier RJ, Tirosh B, Shibolet O. HCV causes chronic endoplasmic reticulum stress leading to adaptation and interference with the unfolded protein response. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeganeh B. Characterization of lung adenocarcinoma in transgenic mice overexpressing calreticulin under control of the Tie-2 promoter 2010, PhD Thesis, University of Manitoba. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/1993/4239.

- 29.Ghavami S, Sharma P, Yeganeh B, Ojo OO, Jha A, Mutawe MM, Kashani HH, Los MJ, Klonisch T, Unruh H, et al. Airway mesenchymal cell death by mevalonate cascade inhibition: integration of autophagy, unfolded protein response and apoptosis focusing on Bcl2 family proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843:1259–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jangamreddy JR, Ghavami S, Grabarek J, Kratz G, Wiechec E, Fredriksson BA, Rao Pariti RK, Cieślar-Pobuda A, Panigrahi S, Łos MJ. Salinomycin induces activation of autophagy, mitophagy and affects mitochondrial polarity: differences between primary and cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:2057–2069. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghavami S, Mutawe MM, Schaafsma D, Yeganeh B, Unruh H, Klonisch T, Halayko AJ. Geranylgeranyl transferase 1 modulates autophagy and apoptosis in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L420–L428. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00312.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghavami S, Hashemi M, Ande SR, Yeganeh B, Xiao W, Eshraghi M, Bus CJ, Kadkhoda K, Wiechec E, Halayko AJ, et al. Apoptosis and cancer: mutations within caspase genes. J Med Genet. 2009;46:497–510. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.066944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaabane W, Cieślar-Pobuda A, El-Gazzah M, Jain MV, Rzeszowska-Wolny J, Rafat M, Stetefeld J, Ghavami S, Los MJ. Human-gyrovirus-Apoptin triggers mitochondrial death pathway--Nur77 is required for apoptosis triggering. Neoplasia. 2014;16:679–693. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chevet E, Hetz C, Samali A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-activated cell reprogramming in oncogenesis. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:586–597. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villano SA, Vlahov D, Nelson KE, Cohn S, Thomas DL. Persistence of viremia and the importance of long-term follow-up after acute hepatitis C infection. Hepatology. 1999;29:908–914. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schuchmann M, Galle PR. Apoptosis in liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:785–790. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zekri AR, Bahnassy AA, Hafez MM, Hassan ZK, Kamel M, Loutfy SA, Sherif GM, El-Zayadi AR, Daoud SS. Characterization of chronic HCV infection-induced apoptosis. Comp Hepatol. 2011;10:4. doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-10-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mankouri J, Dallas ML, Hughes ME, Griffin SD, Macdonald A, Peers C, Harris M. Suppression of a pro-apoptotic K+ channel as a mechanism for hepatitis C virus persistence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15903–15908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906798106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otsuka M, Kato N, Taniguchi H, Yoshida H, Goto T, Shiratori Y, Omata M. Hepatitis C virus core protein inhibits apoptosis via enhanced Bcl-xL expression. Virology. 2002;296:84–93. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bantel H, Schulze-Osthoff K. Apoptosis in hepatitis C virus infection. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10 Suppl 1:S48–S58. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cougot D, Neuveut C, Buendia MA. HBV induced carcinogenesis. J Clin Virol. 2005;34 Suppl 1:S75–S78. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(05)80014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waghray A, Murali AR, Menon KN. Hepatocellular carcinoma: From diagnosis to treatment. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:1020–1029. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i8.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chan HLY, Sung JJY. Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B virus. Proceedings of the Seminars in liver disease. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2006. pp. 153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fung J, Lai CL, Yuen MF. Hepatitis B and C virus-related carcinogenesis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:964–970. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanda T, Yokosuka O, Imazeki F, Yamada Y, Imamura T, Fukai K, Nagao K, Saisho H. Hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx)-induced apoptosis in HuH-7 cells: influence of HBV genotype and basal core promoter mutations. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:478–485. doi: 10.1080/00365520310008719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen HS, Kaneko S, Girones R, Anderson RW, Hornbuckle WE, Tennant BC, Cote PJ, Gerin JL, Purcell RH, Miller RH. The woodchuck hepatitis virus X gene is important for establishment of virus infection in woodchucks. J Virol. 1993;67:1218–1226. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1218-1226.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Su F, Schneider RJ. Hepatitis B virus HBx protein sensitizes cells to apoptotic killing by tumor necrosis factor alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8744–8749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chirillo P, Pagano S, Natoli G, Puri PL, Burgio VL, Balsano C, Levrero M. The hepatitis B virus X gene induces p53-mediated programmed cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8162–8167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim HJ, Kim SY, Kim J, Lee H, Choi M, Kim JK, Ahn JK. Hepatitis B virus X protein induces apoptosis by enhancing translocation of Bax to mitochondria. IUBMB Life. 2008;60:473–480. doi: 10.1002/iub.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee YI, Hwang JM, Im JH, Lee YI, Kim NS, Kim DG, Yu DY, Moon HB, Park SK. Human hepatitis B virus-X protein alters mitochondrial function and physiology in human liver cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15460–15471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309280200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Terradillos O, Pollicino T, Lecoeur H, Tripodi M, Gougeon ML, Tiollais P, Buendia MA. p53-independent apoptotic effects of the hepatitis B virus HBx protein in vivo and in vitro. Oncogene. 1998;17:2115–2123. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim KH, Seong BL. Pro-apoptotic function of HBV X protein is mediated by interaction with c-FLIP and enhancement of death-inducing signal. EMBO J. 2003;22:2104–2116. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang WH, Grégori G, Hullinger RL, Andrisani OM. Sustained activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathways by hepatitis B virus X protein mediates apoptosis via induction of Fas/FasL and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 1/TNF-alpha expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10352–10365. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.23.10352-10365.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marusawa H, Matsuzawa S, Welsh K, Zou H, Armstrong R, Tamm I, Reed JC. HBXIP functions as a cofactor of survivin in apoptosis suppression. EMBO J. 2003;22:2729–2740. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elmore LW, Hancock AR, Chang SF, Wang XW, Chang S, Callahan CP, Geller DA, Will H, Harris CC. Hepatitis B virus X protein and p53 tumor suppressor interactions in the modulation of apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14707–14712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clippinger AJ, Gearhart TL, Bouchard MJ. Hepatitis B virus X protein modulates apoptosis in primary rat hepatocytes by regulating both NF-kappaB and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J Virol. 2009;83:4718–4731. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02590-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Diao J, Khine AA, Sarangi F, Hsu E, Iorio C, Tibbles LA, Woodgett JR, Penninger J, Richardson CD. X protein of hepatitis B virus inhibits Fas-mediated apoptosis and is associated with up-regulation of the SAPK/JNK pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8328–8340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yun C, Um HR, Jin YH, Wang JH, Lee MO, Park S, Lee JH, Cho H. NF-kappaB activation by hepatitis B virus X (HBx) protein shifts the cellular fate toward survival. Cancer Lett. 2002;184:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Degenhardt K, Mathew R, Beaudoin B, Bray K, Anderson D, Chen G, Mukherjee C, Shi Y, Gélinas C, Fan Y, et al. Autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and restricts necrosis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ke PY, Chen SS. Autophagy: a novel guardian of HCV against innate immune response. Autophagy. 2011;7:533–535. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.5.14732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:107–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee HK, Iwasaki A. Autophagy and antiviral immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin LT, Dawson PW, Richardson CD. Viral interactions with macroautophagy: a double-edged sword. Virology. 2010;402:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kudchodkar SB, Levine B. Viruses and autophagy. Rev Med Virol. 2009;19:359–378. doi: 10.1002/rmv.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vescovo T, Refolo G, Romagnoli A, Ciccosanti F, Corazzari M, Alonzi T, Fimia GM. Autophagy in HCV infection: keeping fat and inflammation at bay. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:265353. doi: 10.1155/2014/265353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chiramel AI, Brady NR, Bartenschlager R. Divergent roles of autophagy in virus infection. Cells. 2013;2:83–104. doi: 10.3390/cells2010083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dreux M, Chisari FV. Impact of the autophagy machinery on hepatitis C virus infection. Viruses. 2011;3:1342–1357. doi: 10.3390/v3081342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sir D, Chen WL, Choi J, Wakita T, Yen TS, Ou JH. Induction of incomplete autophagic response by hepatitis C virus via the unfolded protein response. Hepatology. 2008;48:1054–1061. doi: 10.1002/hep.22464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dreux M, Gastaminza P, Wieland SF, Chisari FV. The autophagy machinery is required to initiate hepatitis C virus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14046–14051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907344106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Imran M, Waheed Y, Manzoor S, Bilal M, Ashraf W, Ali M, Ashraf M. Interaction of Hepatitis C virus proteins with pattern recognition receptors. Virol J. 2012;9:126. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Deretic V, Saitoh T, Akira S. Autophagy in infection, inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:722–737. doi: 10.1038/nri3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sir D, Tian Y, Chen WL, Ann DK, Yen TS, Ou JH. The early autophagic pathway is activated by hepatitis B virus and required for viral DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4383–4388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911373107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tang H, Da L, Mao Y, Li Y, Li D, Xu Z, Li F, Wang Y, Tiollais P, Li T, et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein sensitizes cells to starvation-induced autophagy via up-regulation of beclin 1 expression. Hepatology. 2009;49:60–71. doi: 10.1002/hep.22581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li J, Liu Y, Wang Z, Liu K, Wang Y, Liu J, Ding H, Yuan Z. Subversion of cellular autophagy machinery by hepatitis B virus for viral envelopment. J Virol. 2011;85:6319–6333. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02627-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tian Y, Sir D, Kuo CF, Ann DK, Ou JH. Autophagy required for hepatitis B virus replication in transgenic mice. J Virol. 2011;85:13453–13456. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06064-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Favreau DJ, Desforges M, St-Jean JR, Talbot PJ. A human coronavirus OC43 variant harboring persistence-associated mutations in the S glycoprotein differentially induces the unfolded protein response in human neurons as compared to wild-type virus. Virology. 2009;395:255–267. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang S, Kaufman RJ. The impact of the unfolded protein response on human disease. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:857–867. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201110131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Galindo I, Hernáez B, Muñoz-Moreno R, Cuesta-Geijo MA, Dalmau-Mena I, Alonso C. The ATF6 branch of unfolded protein response and apoptosis are activated to promote African swine fever virus infection. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e341. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jheng JR, Lau KS, Tang WF, Wu MS, Horng JT. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is induced and modulated by enterovirus 71. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:796–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Qian Z, Xuan B, Chapa TJ, Gualberto N, Yu D. Murine cytomegalovirus targets transcription factor ATF4 to exploit the unfolded-protein response. J Virol. 2012;86:6712–6723. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00200-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rathore AP, Ng ML, Vasudevan SG. Differential unfolded protein response during Chikungunya and Sindbis virus infection: CHIKV nsP4 suppresses eIF2α phosphorylation. Virol J. 2013;10:36. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stahl S, Burkhart JM, Hinte F, Tirosh B, Mohr H, Zahedi RP, Sickmann A, Ruzsics Z, Budt M, Brune W. Cytomegalovirus downregulates IRE1 to repress the unfolded protein response. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003544. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jones DM, McLauchlan J. Hepatitis C virus: assembly and release of virus particles. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22733–22739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.133017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ke PY, Chen SS. Activation of the unfolded protein response and autophagy after hepatitis C virus infection suppresses innate antiviral immunity in vitro. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:37–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI41474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Joyce MA, Walters KA, Lamb SE, Yeh MM, Zhu LF, Kneteman N, Doyle JS, Katze MG, Tyrrell DL. HCV induces oxidative and ER stress, and sensitizes infected cells to apoptosis in SCID/Alb-uPA mice. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000291. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tardif KD, Mori K, Siddiqui A. Hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicons induce endoplasmic reticulum stress activating an intracellular signaling pathway. J Virol. 2002;76:7453–7459. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.15.7453-7459.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chan SW, Egan PA. Hepatitis C virus envelope proteins regulate CHOP via induction of the unfolded protein response. FASEB J. 2005;19:1510–1512. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3455fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ciccaglione AR, Costantino A, Tritarelli E, Marcantonio C, Equestre M, Marziliano N, Rapicetta M. Activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress response by hepatitis C virus proteins. Arch Virol. 2005;150:1339–1356. doi: 10.1007/s00705-004-0487-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ciccaglione AR, Marcantonio C, Tritarelli E, Equestre M, Vendittelli F, Costantino A, Geraci A, Rapicetta M. Activation of the ER stress gene gadd153 by hepatitis C virus sensitizes cells to oxidant injury. Virus Res. 2007;126:128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Top D, Barry C, Racine T, Ellis CL, Duncan R. Enhanced fusion pore expansion mediated by the trans-acting Endodomain of the reovirus FAST proteins. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000331. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tardif KD, Mori K, Kaufman RJ, Siddiqui A. Hepatitis C virus suppresses the IRE1-XBP1 pathway of the unfolded protein response. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17158–17164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312144200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zheng Y, Gao B, Ye L, Kong L, Jing W, Yang X, Wu Z, Ye L. Hepatitis C virus non-structural protein NS4B can modulate an unfolded protein response. J Microbiol. 2005;43:529–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kroemer G, Mariño G, Levine B. Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell. 2010;40:280–293. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gripon P, Rumin S, Urban S, Le Seyec J, Glaise D, Cannie I, Guyomard C, Lucas J, Trepo C, Guguen-Guillouzo C. Infection of a human hepatoma cell line by hepatitis B virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15655–15660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232137699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Reimold AM, Etkin A, Clauss I, Perkins A, Friend DS, Zhang J, Horton HF, Scott A, Orkin SH, Byrne MC, et al. An essential role in liver development for transcription factor XBP-1. Genes Dev. 2000;14:152–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Isler JA, Skalet AH, Alwine JC. Human cytomegalovirus infection activates and regulates the unfolded protein response. J Virol. 2005;79:6890–6899. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6890-6899.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lazar C, Uta M, Branza-Nichita N. Modulation of the unfolded protein response by the human hepatitis B virus. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:433. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]