Abstract

AIM: To analyze through meta-analyses the benefits of two types of stents in the inoperable malignant biliary obstruction.

METHODS: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials (RCT) was conducted, with the last update on March 2015, using EMBASE, CINAHL (EBSCO), MEDLINE, LILACS/CENTRAL (BVS), SCOPUS, CAPES (Brazil), and gray literature. Information of the selected studies was extracted in sight of six outcomes: primarily regarding dysfunction, complication and re-intervention rates; and secondarily costs, survival, and patency time. The data about characteristics of trial participants, inclusion and exclusion criteria and types of stents were also extracted. The bias was mainly assessed through the JADAD scale. This meta-analysis was registered in the PROSPERO database by the number CRD42014015078. The analysis of the absolute risk of the outcomes was performed using the software RevMan, by computing risk differences (RD) of dichotomous variables and mean differences (MD) of continuous variables. Data on RD and MD for each primary outcome were calculated using the Mantel-Haenszel test and inconsistency was qualified and reported in χ2 and the Higgins method (I2). Sensitivity analysis was performed when heterogeneity was higher than 50%, a subsequent assay was done and other findings were compiled. Student’s t-test was used for the comparison of weighted arithmetic means regarding secondary outcomes.

RESULTS: Initial searching identified 3660 studies; 3539 were excluded through title, repetition, and/or abstract, while 121 studies were fully assessed and were excluded mainly because they did not compare self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) and plastic stents (PS), leading to thirteen RCT selected, with 13 articles and 1133 subjects meta-analyzed. The mean age was 69.5 years old, that were affected mostly by bile duct (proximal) and pancreatic tumors (distal). The preferred SEMS diameter used was the 10 mm (30 Fr) and the preferred PS diameter used was 10 Fr. In the meta-analysis, SEMS had lower overall stent dysfunction compared to PS (21.6% vs 46.8%, P < 0.00001) and fewer re-interventions (21.6% vs 56.6%, P < 0.00001), with no difference in complications (13.7% vs 15.9%, P = 0.16). In the secondary analysis, the mean survival rate was higher in the SEMS group (182 d vs 150 d, P < 0.0001), with a higher patency period (250 d vs 124 d, P < 0.0001) and a lower cost per patient (4193.98 vs 4728.65 Euros, P < 0.0985).

CONCLUSION: SEMS are associated with lower stent dysfunction, lower re-intervention rates, better survival, and higher patency time. Complications and costs showed no difference.

Keywords: Biliary tract neoplasms, Malignant biliary obstruction, Jaundice, Palliative care, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, Stent, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Core tip: Endoscopic stenting is accepted worldwide as the first choice palliative treatment for malignant biliary obstruction. There are still two types of materials currently being used, which are plastic and metal. Therefore, many doubts are raised as to which one is the most beneficial to the patient. This review gathers the highest quality information available about these two types of stent, giving information in regards to dysfunction, complication, re-intervention rates, costs, survival, and patency time; and intend to help handle clinical practice nowadays, especially in countries where the availability of metallic stents is scarce and cannot be offered to all patients.

INTRODUCTION

Biliary tract neoplasms are uncommon yet important pathologies. Their main symptom (jaundice) can cause important disorders, such as immunosuppression[1-4], and prognosis is usually poor[5]. Despite their rarity, estimates from the SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results) database from North America reveal increased incidence and a maintained poor prognosis[6].

It is estimated that almost 20% of the subclinical jaundice is due to malignant bile duct obstruction[7], divided about 2/3 to 1/3 between pancreatic and other biliary obstructive cancers, respectively[8].

Because of its invasiveness and late symptom appearance and onset in elderly people, the majority of the diagnosed cases are not deemed curable by resection[9-11]. According to INCA (Brazilian’s National Institute of Cancer) pancreatic tumors accounted for 2% of the malignant tumors of Brazil, with an estimate of around 17000 new cases in 2015. Having in mind that only 15%-20% of these neoplasms are resectable, the number of inoperable malignant biliary obstruction (MBO) just in Brazil in 2015 has been estimated at over 13000[12].

The use of palliative methods is essential in these cases and endoscopic biliary stenting is becoming more prevalent, especially in high operative risk cases or very ill patients, because it is minimally invasive[13,14]. The subject of the quality and durability of the palliative methods is becoming more important due to skyrocketing survival in advanced stages biliary tract neoplasms. For instance, Kim et al[15] demonstrated a survival in metastatic biliary tract cancer of about 9 mo in a phase II study of gemcitabine and S-1 combination chemotherapy, in contrast of the 3-4 mo survival of earlier studies.

Two types of stents are routinely used in current practice: plastic stents (PS) and self-expanding metal stents (SEMS). Several randomized clinical trials (RCT) demonstrated that metal stents are associated with longer stent patency but survival is the same as when plastic stents are used. Some studies favored SEMS[16-25] and some favored PS[26,27], although the difference about survival has only been shown in one study, favoring SEMS[28].

The latest meta-analysis regarding metal and plastic stenting in malignant biliary obstruction[29], which involved stents inserted through percutaneous transhepatic drainage and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), published in January 2013 and involving ten RCT, demonstrated the same information about stent patency and re-intervention rates, although it also demonstrated a diminished survival in the PS group. This meta-analysis aims to use the 4 RCT not included in the last study.

Considering the acceptable use of either SEMS or PS in endoscopic stenting for inoperable MBO, this meta-analyses aims to gather applicable information, primarily regarding dysfunction, complication and re-intervention rates; and secondarily costs, survival, and patency time.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

This meta-analysis was registered in the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic review[30], by the number CRD42014015078.

All assessed randomized clinical trials regarding comparisons between SEMS and PS that were endoscopically placed for MBO were collected from these databases: EMBASE, CINAHL (EBSCO), MEDLINE, LILACS and CENTRAL (BVS), SCOPUS, Master’s and Doctorate’s theses and dissertations on the CAPES database (Brazil)[31], and gray literature. Any outcome was considered, from any date of publication until March 2015, with any number of subjects. Publications were accepted in any format, language, or publication status.

Besides searching through the tools mentioned above, we conducted a direct approach by emailing authors, when necessary. The last date the databases were assessed for new releases was March 15, 2015.

The search strategies used for MEDLINE, SCOPUS and EMBASE databases are stated in supplementary material; the Brazilian Master’s and Doctorate’s thesis and dissertations strategy was the word “stent”; CINAHAL, LILACS and CENTRAL strategies were “plastic stent OR metallic stent (filter - randomized controlled trials)”.

Study selection

Initially, studies were excluded because clear information in the title or abstract stated that it did not compare stent techniques or did not study MBO. Furthermore, the abstracts and full articles were assessed and excluded if proven not to be RCT or the comparison was not between SEMS and PS.

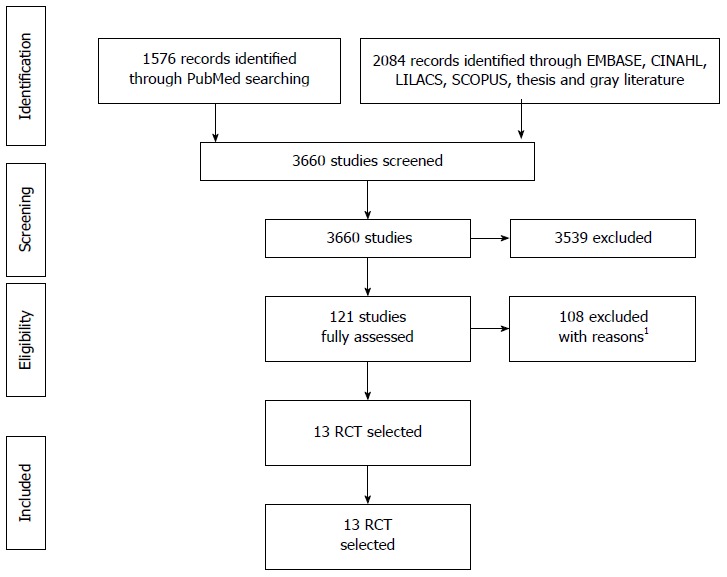

Initial searching identified 3660 studies; 3539 were excluded through title, repetition, and/or abstract (Figure 1). One hundred and twenty-one studies were fully assessed and were excluded mainly because they did not compare PS and SEMS. One of the studies included in the last meta-analysis of Hong et al[29] was not used because it involved only percutaneous transhepatic drainage. Two authors were contacted through email regarding two studies that, later on, proved unfit for this systematic review; the reasons are shown in Supplementary Table 1, in the supplementary material. In addition, there were some studies that were previews of later ones, and thus were also excluded after confirmation. Detailed information about the findings by database and reasons for exclusion can be found in the supplementary material.

Figure 1.

PRISMA’s studies selection fluxogram. 1The reasons for exclusions are displayed on Supplementary Table 1. RCT: Randomized clinical trials.

Table 1.

Neoplasms distribution in individual studies

| Ref. | No. of patients | Bile duct cancer (%) | Pancreatic tumor (%) | Papilae tumor (%) | Gallbladder cancer (%) | Metastatic tumor (%) | Other (%) |

| Walter et al 2014 | 2401 | 0 | 83 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Moses et al 2013 | 85 | 0 | 69 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 15 |

| Mukai et al 2013 | 60 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 28 | 0 |

| Sangchan et al 2012 | 108 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bernon et al 2011 | 22 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Isayama et al 2011 | 120 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Soderlund et al 2006 | 100 | 9 | 78 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 4 |

| Katsinelos et al 2006 | 47 | 17 | 53 | 11 | 0 | 19 | 0 |

| Kaassis et al 2003 | 118 | 15 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Prat et al 1998 | 1051 | 21 | 64 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| Wagner et al 1993 | 20 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Knyrim et al 1993 | 62 | 3 | 69 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 23 |

| Davids et al 1992 | 105 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Not all patients were included in the meta-analysis.

Data extraction

The data were extracted from all the databases mentioned by two independent authors, confirming the same eligible final studies. The eligible studies were confronted after both authors stopped article exclusion.

The dysfunction outcome was accessed through the number of patients who had occlusion, migration, or kinking of the first stent used; therefore any disorder, confirmed or presumed because of cholestasis, that needed a re-intervention.

Re-intervention was any procedure needed for a new drainage of the biliary tree, endoscopic or percutaneous, to replace a dysfunctional stent.

The complication outcome was any disorder attributed to the stent insertion that required a medical intervention at the time of diagnosis, but not obligatorily related to stent dysfunction (pancreatitis, cholangitis, bleeding, perforation, cholecystitis, liver abscess).

The outcome of costs was calculated using the data presented in the studies and converted to Euro (€), regardless of whether they concerned the full treatment, or using stent value and the number of stents exchanged only. Stent patency time was the mean time to stent dysfunction, calculated in days. Overall survival was calculated through the reported mean time of survival in days. If the study used months, each month was considered as having 30 d.

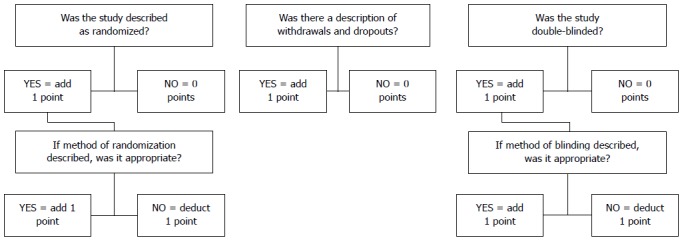

Risk of bias

The biases were individually assessed through the JADAD scale[32] (Figure 2), a tool to assess a RCT quality through evaluation of blinding, randomization, and losses reported. In addition, biases were evaluated regarding intention to treat, prognosis characteristics, regional differences, amount of losses, and follow up; these were not used as exclusion criteria.

Figure 2.

JADAD scale.

Although no restrictions were made for language in the present study, it has a publication bias since the search databases used required that studies have abstracts in English or Portuguese. Therefore, studies in other languages that did not have at least an abstract in English were not assessed. The differences between the study population, type of cancer, and type and diameter of stent were considered as possible biases.

Statistical analysis

Regarding meta-analysis, the difference was calculated as the risk difference for dichotomic variables with a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test with a 95%CI, and as the mean difference with fixed effect using inverse variance, with a 95%CI, for continuous variables. The semi-quantitative measures were described as the weighted arithmetic mean using the patient number of each study, with standard deviation, and Student’s t-test analysis. All data were addressed as intention to treat analysis (ITT).

RevMan 5 software (Review Manager version 5.3.5 - Cochrane Collaboration, Copyright © 2014) was used for meta-analysis of stent dysfunction, complication, and re-intervention rates. Student’s t-test was used for the comparison of weighted arithmetic means regarding costs, survival, and stent patency, as we could not extract the standard deviation of this data from most of the studies selected. The heterogeneity was evaluated through a χ2 test (I2, or χ2), and modified up to 50% with sensitive analysis, when possible and necessary.

Additional analysis

The studies were further divided between proximal (MPBO) and distal (MDBO) obstruction, and JADAD ≥ 3 and JADAD < 3 for meta-analysis.

RESULTS

Studies characteristics

A total of 13 RCT were selected, with 1133 patients (mean age of 69.5 years old) affected mostly by bile duct (MPBO) and pancreatic tumors (MDBO). Apart from the most common causes of biliary obstruction, 5 papers had description of metastatic tumors causing this obstruction, probably caused by extrinsic compression. Moses et al[27] had around 10% of metastatic cancer from a primary location of colon and lung; Mukai et al[17] had about 30% of metastatic cancer as cause for obstruction while Soderlund et al[20] found 7%, although no information about the primary site was described for neither; Katsinelos et al[21] describes compressive lymph nodes as cause for 19% of the obstructions, while Prat et al[26] had 12%. The preferred SEMS diameter used was the 10 mm (30 Fr) and the preferred PS diameter used was 10 Fr. Detailed data regarding the etiology of the MBO can be found in Table 1. Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 have information about outcomes and specific stent used and can be found in the supplementary material. All the extractable data used in the calculations are exposed in Supplementary Table 4.

Table 2.

Costs evaluation - per patient in Euros

|

Costs (€) |

||||||

|

PS |

SEMS |

|||||

| Ref. | No pts | PS cost (mean) | Total | No pts | SEMS cost (mean) | Total |

| Walter et al, 2014 | 73 | 6906 | 504138 | 146 | 6437 | 939802 |

| Mukai et al, 2013 | 30 | 17170.19 | 515105.7 | 30 | 8935.68 | 268070.4 |

| Soderlund et al, 2006 | 51 | 953.1372549 | 48610 | 49 | 940 | 46060 |

| Katsinelos et al, 2006 | 24 | 737.5 | 17700 | 23 | 1308.695652 | 30100 |

| Kaassis et al, 2003 | 59 | 1216.805085 | 71791.5 | 59 | 1208.116949 | 71278.9 |

| Prat et al, 1998 | 33 | 5547 | 183051 | 34 | 4643 | 157862 |

| Wagner et al, 1993 | 10 | 3511.31 | 35113.1 | 10 | 2552.57 | 25525.7 |

| Knyrim et al, 1993 | 31 | 3067.75 | 95100.25 | 31 | 2045.17 | 63400.27 |

| MEAN (per patient) | 4728.648071 | 4193.977147 | ||||

| SD | 5434.740692 | 2905.677081 | ||||

| P = 0.0985 | ||||||

SEMS: Self-expanding metal stents; PS: Plastic stents.

Table 3.

Time for stent dysfunction - mean time per author in days

| Time for dysfunction in days | ||

| Ref. | PS | SEMS |

| Walter et al, 2014 | 172 | 293.3 |

| Moses et al, 2013 | 153.3 | 385.3 |

| Mukai et al, 2013 | 112 | 359 |

| Sangchan et al, 2012 | 35 | 103 |

| Isayama et al, 2011 | 202 | 285 |

| Soderlund et al, 2006 | 54 | 108 |

| Katsinelos et al, 2006 | 123.5 | 255 |

| Prat et al, 1998 | 96 | 144 |

| Davids et al, 1992 | 126 | 273 |

| MEAN | 123.7261792 | 250.2537988 |

| SD | 53.38757918 | 104.0647031 |

| P < 0.0001 | ||

SEMS: Self-expanding metal stents; PS: Plastic stents.

Risk of bias within studies

The maximum score in the JADAD scale[32] was 3 because it is not possible to have a double-blind study in this field. In total, there were 6 studies with JADAD 1, 2 studies with JADAD 2, and 5 studies with JADAD 3. Overall, survival did not include information about neoplasm-specific mortality. The studies did not always give strict specifications about the stent’s type, nor about inoperable criteria. The use of one abstract[19] also negatively impacted the information that could be assessed; however, the information given was sufficient for some outcomes. Prat et al[26] only had the number of ERCP performed because of dysfunction (accordingly, this was the number used for the dysfunction outcome) and excluded people who lived farther than 150 km from the hospital, leading to a possible bias; also, there was no information about the currency used for cost calculation, but because the study was conducted in France, it was considered as the Euro. In addition, the study had three groups, one of which was not used in our meta-analysis because the outcomes analyzed would be biased (the group had scheduled stent exchange regardless of the patients’ symptoms). Walter et al[16] performed the randomization before the ERCP but excluded some individuals after it. Despite the intent of using ITT analysis for this study, the information on which randomized group the excluded patients were from was not available. Moreover, the information about the mean survival time specified per stent was not obtainable. Five studies[16,17,20,23,25] used the combined approach (rendezvous) or PTC when the endoscopic approach alone was insufficient. All studies selected were RCT with no selection bias.

Results of individual studies

All studies had extractable information about stent dysfunction, ten about re-intervention (although Walter et al[16] was not used because the lack of standard deviation data), and eleven about complication; these were used in the meta-analysis. Eleven studies had comparative information on overall survival, eight on costs and ten on stent patency time (Kaassis et al[22] had information only about the PS group), although the information did not include the standard deviation (SD), which compromised our intent for quantitative analysis. Therefore, these three latest outcomes were evaluated semi-quantitatively. Overall, the results regarding stent dysfunction, time of stent patency, and re-intervention were homogenously beneficial towards SEMS in all studies. Regarding costs, complications, and survival, the results were discrepant.

Synthesis of results

The results were divided between quantitative and semi-quantitative results because of the absence of vital information for quantitative analysis of all outcomes.

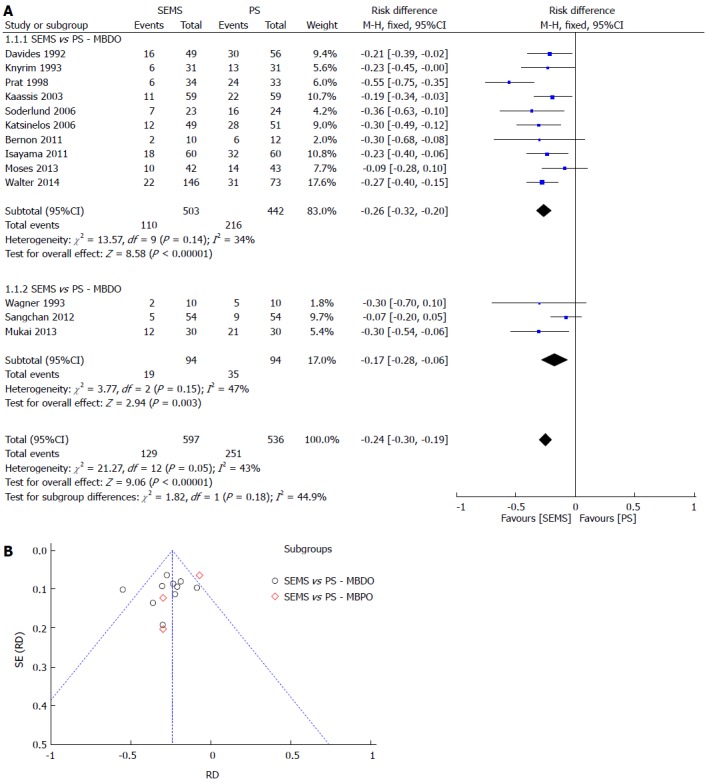

Primary outcomes: The dysfunction rate was 24% lower in the SEMS group, with a NNT of 5. The sensitive analysis lowered the heterogeneity to 0% (withdrawing data from Prat et al[26]) with no change to the result. The meta-analysis graph was divided between MBDO (1.1.1) and MBPO (1.1.2) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Stent dysfunction. A: Forest plot; B: Funnel plot.

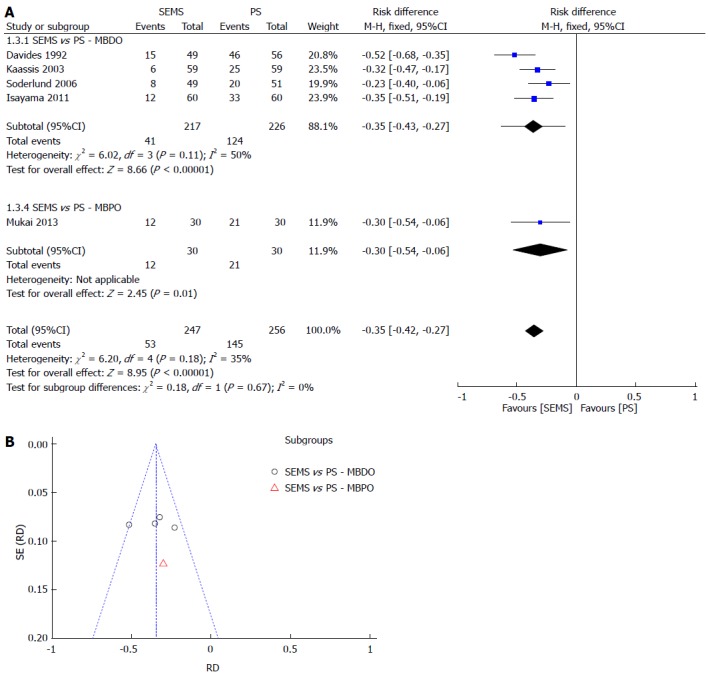

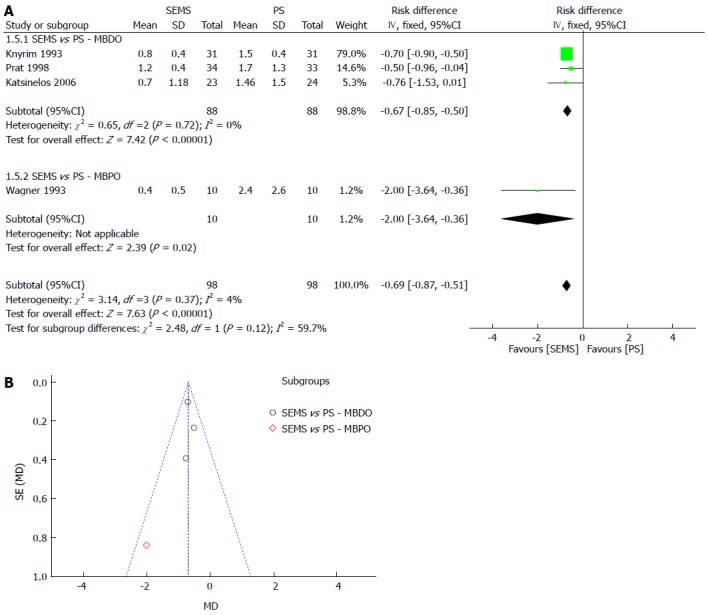

Re-intervention was separated into dichotomous and continuous data, corresponding to the data reported by the author, except for Katsinelos et al[21], whose data were transformed into continuous for statistical analysis purposes. In both meta-analyses, SEMS had at least 30% fewer re-interventions and a NNT of 3. The meta-analysis graph was divided between MBDO (1.3.1/1.5.1) and MBPO (1.3.2/1.5.2) (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

RE-INTERVENTION (dichotomic). A: Forest plot; B: Funnel plot.

Figure 5.

RE-INTERVENTION (continuous). A: Forest plot; B: Funnel plot.

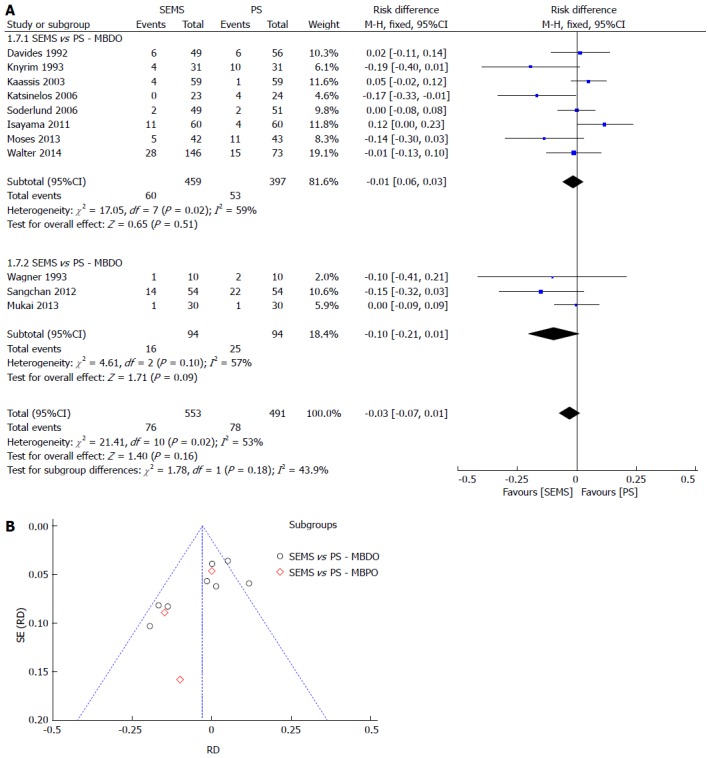

MBO complication rates were not different between PS or SEMS. Even after sensitivity analysis (with the lowest heterogeneity of 0%, withdrawing 5 studies), the result remained the same. The meta-analysis graph was divided between MBDO (1.7.1) and MBPO (1.7.2) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Complication. A: Forest plot; B: Funnel plot.

Secondary outcomes: In the costs analysis, the SEMS group had a less expensive result, although without statistical significance, with a mean of €4193.98 for SEMS vs €4728.65 for PS (P = 0.0985) (Table 2).

The time for stent dysfunction was measured in days and was statistically higher in the SEMS group (250 vs 124 d, P < 0.0001) (Table 3).

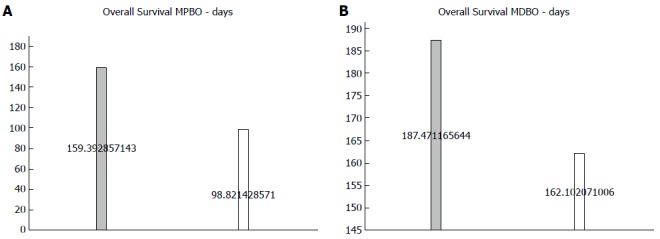

Regarding survival, also measured in days, SEMS had a better result. The outcome was divided in MDBO and MPBO because of the different causes of malignant obstruction between the two, therefore we tried to minimize the bias of the worse survival in hilar tumors. Nevertheless, apart from a global minor survival in the MPBO for the both stents comparing to MDBO, SEMS had a longer survival, with statistical significance in MPBO and MDBO alike (Figure 7). Detailed data regarding survival of each study can be found in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 7.

Mean survival by stent in patients (P < 0.0001). A: With proximal tumors; B: With distal tumors.

Risk of bias across studies

The definition of dysfunction varied from study to study, but always indicated an improper drainage requiring re-intervention. The costs were measured by the studies in Deutsche Marks, Japanese Yen, and Euros. The values were all converted to Euro to lessen the conversion error, as the majority of the results were in this currency. The fare of the month and year of the last included patient was used for Mukai et al[17], and the fare of February 1999 for earlier studies, using the database of Brazil’s Central Bank[33]. The costs have another bias, as most studies considered the whole treatment (i.e., ICU, ERCP initial and re-intervention, stents, hostelry, drugs, and laboratory), while Katsinelos et al[21] accounted only for the prosthesis itself Katsinelos et al[21].

The invasiveness, other than “inoperable tumor” and the patient performance status, was not globally reported and the exclusion criteria differed between the studies, with populations from 28% Prat et al[26] to 71% Moses et al[27] with liver metastasis. This probably was a bias between studies for the overall survival and time to stent dysfunction comparisons, because of prognostic differences. Also, the younger mean age of the patients in Davids et al[23] could have influenced the prognosis.

There was also bias regarding the different types of stents used in the studies (uSEMS, pcSEMS and cSEMS; Amsterdam and Tannenbaum PS), and the number of stents used in the same procedure.

Additional analysis

The studies were divided between MBPO and MBDO and therefore analyzed in the same way. We also analyzed the subgroups with JADAD ≥ 3 and JADAD < 3. The subgroup analysis did not change the previously-stated results, hence the graphs are located in the supplementary material. The meta-analysis graph was divided between JADAD ≥ 3 (1.2.1/1.4.1/1.6.1/1.8.1) and JADAD < 3 (1.2.2/1.4.2/1.6.2/1.8.2), found in Supplementary Figures 3-10.

DISCUSSION

The use of SEMS has fewer dysfunction, longer patency, and longer survival. It requires fewer re-interventions, with no differences in complication rate or costs, when compared to PS.

Regarding the patients’ quality of life and adequate palliative care with the lowest hospital stay possible and minimal symptomatology, SEMS are always the first option, as there is no definitive way to determine one’s life expectancy, despite the known mean survival rates according to the stage of the disease[34-36]. From the perspective of the healthcare system and the rational use of materials, SEMS does not seem to have more to offer than PS for very ill patients (with a life expectancy of less than 4 mo), however with the innovations in chemo and radiotherapy, the life expectancy shall only increase[15]. Therefore, the SEMS could be saved for cases that are more suitable, without compromising adequate palliative care, by considering their mean survival (99-162 d vs 159-187 d, P < 0.0001) and mean patency (124 d vs 250 d, P < 0.0001), compared to PS. This is true especially in countries like Brazil, where SEMS are not widely available for every inoperable MBO, so we could make the most of our limited resources.

The results of sub-analysis did not differ from the main results, so the conclusions can be extrapolated to MPBO and MDBO alike.

New RCT that study the comparison between PS and SEMS, especially regarding quality of life and costs, with explicit tumor staging involved and presenting the means for a meta-analysis (data with standard deviation and tables), are required for advancing the knowledge of palliative care for MBO. These studies could be considered in very ill and poor prognosis patients, with no risk for their optimal palliative treatment.

The lack of information, such as the SD in the costs, overall survival, and patency time outcomes, made some data unsuitable for meta-analysis, despite being adequate for semi-quantitative analysis. The heterogeneity in the costs analysis of each study compromises its adequate comparison. Non-standard and subjective criteria for inoperable patients could have undermined the complication and costs significance, as these may have been different if only metastatic or non-metastatic patients could be clustered.

In conclusion, metal stents are associated with a lower rate of stent dysfunction and lower re-intervention rate, with no difference in complications. SEMS also have better survival rates and a higher patency period with no difference in costs from PS.

COMMENTS

Background

It is estimated that almost 20% of the subclinical jaundice is due to malignant bile duct obstruction, divided about 2/3 to 1/3 between pancreatic and other biliary obstructive cancers, respectively. According to INCA (Brazilian’s National Institute of Cancer), the number of inoperable malignant biliary obstruction (MBO) just in Brazil in 2015 should be over 13000. The use of palliative methods is essential in these cases and endoscopic biliary stenting is becoming more prevalent, especially in high operative risk cases or very ill patients, because it is minimally invasive. Endoscopic stenting is accepted worldwide as the first choice palliative treatment for malignant biliary obstruction. There are still in use two main types of material (plastic and metal), leaving doubts about what should be the best indication for one or the other. This review gathers the most recent quality information about these two types of stent, bringing information regarding dysfunction, complication, re-intervention rates, costs, survival, and patency time; and intend to help handling nowadays clinical practice especially in countries where the availability of metallic stents is scarce and cannot be offered to all patients.

Research frontiers

To choose the better stent for treatment of a patient while saving resources to the other patients with similar conditions is the main question of this meta-analysis.

Innovations and breakthroughs

There are still in use two main types of stent for MBO, and despite the loose belief that plastic stents (PS) are better for short survival patients and self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) are better for long survival patients, there is no consensus or guidelines to determine in what cases the endoscopist can use each.

Applications

This review aims to help with detailed and specific information about each stent to aid physicians and the Health’s Departments around the globe, showing that sometimes the cheapest item can be not so advantageous when you look at the whole treatment. The discrepancy of measures in the selected studies is a limitation. Prospective randomized controlled studies with attention to a specific population (short expected survival) are needed to clarify if the SEMS is actually no better in this group.

Terminology

Malignant biliary obstruction is defined as a cancer being responsible, directly or indirectly, for the mechanical blockage of the bile output, produced by the hepatocytes. Clinically, it usually is suspected because of jaundice. When this cancer cannot be resected, due to the patient’s clinical condition or due to the cancer invasion, it is nominated inoperable. Palliatively, the first choice to treat the symptoms is to place an endoscopic stent, that nowadays can be either made of plastic or metal.

Peer-review

In this meta-analysis, the authors have presented the costs and clinical outcomes of endoscopic stenting with SEMS and PS in patients with inoperable MBO, bringing the information to better understand the advantages and disadvantages of each.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data sharing statement: The technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset are available from the corresponding author at leozorron@gmail.com. No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: May 23, 2015

First decision: July 10, 2015

Article in press: September 30, 2015

P- Reviewer: Seicean A S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Roughneen PT, Didlake R, Kumar SC, Kahan BD, Rowlands BJ. Enhancement of heterotopic cardiac allograft survival by experimental biliary ligation. Transplantation. 1987;43:437–438. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198703000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treglia-Dal Lago M, Jukemura J, Machado MC, da Cunha JE, Barbuto JA. Phagocytosis and production of H2O2 by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with obstructive jaundice. Pancreatology. 2006;6:273–278. doi: 10.1159/000092688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawarabayashi N, Seki S, Hatsuse K, Kinoshita M, Takigawa T, Tsujimoto H, Kawabata T, Nakashima H, Shono S, Mochizuki H. Immunosuppression in the livers of mice with obstructive jaundice participates in their susceptibility to bacterial infection and tumor metastasis. Shock. 2010;33:500–506. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181c4e44a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz SC, Ryan K, Ahmed N, Plitas G, Chaudhry UI, Kingham TP, Naheed S, Nguyen C, Somasundar P, Espat NJ, et al. Obstructive jaundice expands intrahepatic regulatory T cells, which impair liver T lymphocyte function but modulate liver cholestasis and fibrosis. J Immunol. 2011;187:1150–1156. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans DB, Farnell MB, Lillemoe KD, Vollmer C, Strasberg SM, Schulick RD. Surgical treatment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreas cancer: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1736–1744. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reisman Y, Gips CH, Lavelle SM, Wilson JH. Clinical presentation of (subclinical) jaundice--the Euricterus project in The Netherlands. United Dutch Hospitals and Euricterus Project Management Group. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:1190–1195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carriaga MT, Henson DE. Liver, gallbladder, extrahepatic bile ducts, and pancreas. Cancer. 1995;75:171–190. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950101)75:1+<171::aid-cncr2820751306>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1039–1049. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke EC, Jarnagin WR, Hochwald SN, Pisters PW, Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: patterns of spread, the importance of hepatic resection for curative operation, and a presurgical clinical staging system. Ann Surg. 1998;228:385–394. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albores-Saavedra J, Schwartz AM, Batich K, Henson DE. Cancers of the ampulla of vater: demographics, morphology, and survival based on 5,625 cases from the SEER program. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:598–605. doi: 10.1002/jso.21374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Available from: http://www.inca.gov.br/

- 13.Scott EN, Garcea G, Doucas H, Steward WP, Dennison AR, Berry DP. Surgical bypass vs. endoscopic stenting for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:118–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2008.00015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glazer ES, Hornbrook MC, Krouse RS. A meta-analysis of randomized trials: immediate stent placement vs. surgical bypass in the palliative management of malignant biliary obstruction. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim HS, Kim HY, Zang DY, Oh HS, Jeon JY, Cho JW, Park CK, Kim JH, Kim MJ, Ha HI, et al. Phase II study of gemcitabine and S-1 combination chemotherapy in patients with metastatic biliary tract cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015;75:711–718. doi: 10.1007/s00280-015-2687-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walter D, Van Boeckel PG, Groenen M. Metal stent placement is cost-effective for palliation of malignant common bile duct obstruction: A randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79(Suppl 1):5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukai T, Yasuda I, Nakashima M, Doi S, Iwashita T, Iwata K, Kato T, Tomita E, Moriwaki H. Metallic stents are more efficacious than plastic stents in unresectable malignant hilar biliary strictures: a randomized controlled trial. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:214–222. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isayama H, Yasuda I, Ryozawa S, Maguchi H, Igarashi Y, Matsuyama Y, Katanuma A, Hasebe O, Irisawa A, Itoi T, et al. Results of a Japanese multicenter, randomized trial of endoscopic stenting for non-resectable pancreatic head cancer (JM-test): Covered Wallstent versus DoubleLayer stent. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:310–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2011.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernon M, Shaw J, Krige J, Bornman P. Malignant biliary obstruction: A prospective randomised trial comparing plastic and metal stents for palliation of symptomatic jaundice. HPB. 2011;13:139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soderlund C, Linder S. Covered metal versus plastic stents for malignant common bile duct stenosis: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:986–995. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katsinelos P, Paikos D, Kountouras J, Chatzimavroudis G, Paroutoglou G, Moschos I, Gatopoulou A, Beltsis A, Zavos C, Papaziogas B. Tannenbaum and metal stents in the palliative treatment of malignant distal bile duct obstruction: a comparative study of patency and cost effectiveness. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1587–1593. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0778-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaassis M, Boyer J, Dumas R, Ponchon T, Coumaros D, Delcenserie R, Canard JM, Fritsch J, Rey JF, Burtin P. Plastic or metal stents for malignant stricture of the common bile duct? Results of a randomized prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:178–182. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davids PH, Groen AK, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Randomised trial of self-expanding metal stents versus polyethylene stents for distal malignant biliary obstruction. Lancet. 1992;340:1488–1492. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92752-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knyrim K, Wagner HJ, Pausch J, Vakil N. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of metal stents for malignant obstruction of the common bile duct. Endoscopy. 1993;25:207–212. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner HJ, Knyrim K, Vakil N, Klose KJ. Plastic endoprostheses versus metal stents in the palliative treatment of malignant hilar biliary obstruction. A prospective and randomized trial. Endoscopy. 1993;25:213–218. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prat F, Chapat O, Ducot B, Ponchon T, Pelletier G, Fritsch J, Choury AD, Buffet C. A randomized trial of endoscopic drainage methods for inoperable malignant strictures of the common bile duct. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moses PL, Alnaamani KM, Barkun AN, Gordon SR, Mitty RD, Branch MS, Kowalski TE, Martel M, Adam V. Randomized trial in malignant biliary obstruction: plastic vs partially covered metal stents. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8638–8646. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sangchan A, Kongkasame W, Pugkhem A, Jenwitheesuk K, Mairiang P. Efficacy of metal and plastic stents in unresectable complex hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong WD, Chen XW, Wu WZ, Zhu QH, Chen XR. Metal versus plastic stents for malignant biliary obstruction: an update meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:496–500. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/

- 31. Available from: http://www.dominiopublico.gov.br/

- 32.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Available from: http://www4.bcb.gov.br/pec/conversao/conversao.asp.

- 34.Amikura K, Kobari M, Matsuno S. The time of occurrence of liver metastasis in carcinoma of the pancreas. Int J Pancreatol. 1995;17:139–146. doi: 10.1007/BF02788531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kayahara M, Nagakawa T, Ueno K, Ohta T, Takeda T, Miyazaki I. An evaluation of radical resection for pancreatic cancer based on the mode of recurrence as determined by autopsy and diagnostic imaging. Cancer. 1993;72:2118–2123. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931001)72:7<2118::aid-cncr2820720710>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mavros MN, Economopoulos KP, Alexiou VG, Pawlik TM. Treatment and Prognosis for Patients With Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:565–574. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]