Abstract

Introduction:

Cigarette demand, or the change in cigarette consumption as a function of price, is a measure of reinforcement that is associated with level of tobacco dependence and other clinically relevant measures, but the effects of experimentally controlled income on real-world cigarette consumption have not been examined.

Methods:

In this study, income available for cigarette purchases was manipulated to assess the effect on cigarette demand. Tobacco-dependent cigarette smokers (n = 15) who smoked 10–40 cigarettes per day completed a series of cigarette purchasing tasks under a variety of income conditions meant to mimic different weekly cigarette budgets: $280, approximately $127, $70, or approximately $32 per week. Prices of $0.12, $0.25, $0.50, and $1.00 per cigarette were assessed in each income condition. Participants were instructed to purchase as many cigarettes as they would like for the next week and to only consume cigarettes purchased in the context of the study. One price in 1 income condition was randomly chosen to be “real,” and the cigarettes and the excess money in the budget for that condition were given to the participant.

Results:

Results indicate that demand elasticity was negatively correlated with income. Demand intensity (consumption at low prices) was unrelated to income condition and remained high across incomes.

Conclusions:

These results indicate that the amount of income that is available for cigarette purchases has a large effect on cigarette consumption, but only at high prices.

Introduction

Economic demand analyses quantify the relationship between the cost of a commodity and population-level measures of consumption of that commodity. In the case of cigarettes, these analyses largely depend on abrupt fluctuations in price caused by the assessment of new taxes on cigarettes. Studies of this type have found that cigarette consumption is related to price, and that the sensitivity to price, or demand elasticity, is greatest among lower income people.1–3 Behavioral economic demand analyses are analogous to these population-level analyses, but can be used to understand the level of motivation to consume a product on either an individual or small group level, including cigarettes.4,5 This level of analysis allows for experimental manipulations to be made on variables of interest. By quantifying how consumption decreases as costs to obtain and consume a product increase, important indices of demand are obtained. These indices can be grouped into two main measures of consumption, demand intensity and demand elasticity, which are associated with use level and dependence severity.5–8 Demand intensity is the amount of the commodity consumed when available at a very low cost approaching free, and demand elasticity quantifies the degree to which the individual is willing to increase monetary or effort-based expenditures to maintain the same level of consumption as costs increase. Elasticity of demand has been shown to be a characteristic of the drug itself and independent of drug dose.9–11

Demand in humans is typically measured in one of two ways. The first of these consists of laboratory-based measurement where costs are operationalized as the number of behavioral responses to obtain a set amount of the commodity.12 In an exemplar of these procedures, a participant sits in a behavioral assessment booth and pulls a plunger a set amount of times to obtain one or more metered puffs from a cigarette. In subsequent sessions, the number of pulls to earn a unit of puffs increases in a cross-session progressive ratio schedule. This procedure has the advantage of measuring actual consumption in a highly controlled environment, but has the disadvantage of being labor intensive and requiring that consumption occur in a novel, unfamiliar environment with unnatural smoking patterns imposed. The second procedure used to assess behavioral economic demand is the hypothetical purchase task.5,13 In this task, participants are asked to indicate how many cigarettes they would purchase at a range of prices, understanding that their responses are hypothetical and no cigarettes would actually be purchased. This procedure has the advantage of being relatively quick and easy to administer, but is susceptible to participants misjudging their real-world consumption.

Research has shown that demand indices obtained from hypothetical purchase tasks have a high correspondence to other measures of abuse or dependence severity5–8, and other behavioral economic valuation procedures demonstrate high concordance between hypothetical and real rewards.14–17 Additionally, one study has shown that indices obtained from a laboratory-based alcohol purchase task and a hypothetical alcohol purchase task are highly correlated.18 However, no research has measured purchase task behavior in participants’ natural setting for cigarettes or another abused substance, nor has any study measured cigarette demand with a purchase task using experimentally manipulated incomes (i.e., real money supplied by the experimenter that the participants can choose to keep or spend on cigarettes consumed outside the laboratory). A higher amount of experimental income is known to increase choice of a preferred brand of cigarettes over a nonpreferred brand19, but no study has directly manipulated income or to assess the effect on demand intensity and elasticity.

In this study, participants were asked to make weekly cigarette purchases in a potentially real purchase task under a variety of price and income conditions. One of these conditions was actualized, and participants actually purchased the number of cigarettes previously selected with their study budget and kept the remainder of that budget. Participants agreed to only consume experimenter-provided cigarettes for the following week, and report any deviations to this protocol during a 1-week follow-up. The goals of this study were twofold. First, we wanted to measure the effect of cigarette budget (study income) on demand for cigarettes. Second, we wanted to determine if cigarette purchasing amounts in hypothetical purchase tasks corresponded to actual cigarette consumption of cigarettes purchased under the specified conditions. We hypothesized that demand elasticity would be negatively related to income, and that the amounts purchased on the potentially real purchase task would be correlated with the number of cigarettes actually consumed by the participants in the following week, although some deviations between the amount purchased and the amount consumed were expected.

Methods

Participants

Participants (n = 15) were recruited from the local community centered on Roanoke, VA with techniques such as flyers and word-of-mouth referral. To be eligible, participants were required to be 18 years of age, meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text rev; DSM-IV-TR)20 criteria for tobacco dependence, be a regular cigarette smoker who typically smokes between 10 and 40 cigarettes per day, and provide their informed consent. Participants were excluded if they had immediate plans to quit smoking or met DSM-IV-TR dependence criteria for any other drug of abuse. DSM-IV-TR criteria was assessed by asking participants whether each of the DSM-IV-TR criteria applied to them for each drug that they reported using within the past year, and using the recommended DSM-IV-TR criteria for determining dependence based of these endorsements. This study protocol was approved by the Virginia Tech Institutional Review Board.

Participants were 60% female, were 80% white and 13% African American, had a mean age of 41.7 (SD = 11.2), had 14.1 (SD = 1.8) years of education, and had a median monthly income of $900 (interquartile range = $500–$1600). Based on the Timeline Follow- Back assessment, they smoked an average of 18.1 (SD = 6.0) cigarettes per day in the week prior to study onset, and had a mean score of 5.5 (SD = 1.6) on the Fagerström test of nicotine dependence.21

Experimental Design

Upon first contact, potential participants completed a screening questionnaire. Individuals who were eligible based on the screening questionnaire, attended a consent session, and provided their informed consent were enrolled in the study. The single experimental session consisted of questionnaires and tasks to determine participant characteristics and a series of purchasing tasks to measure cigarette consumption under a variety of conditions.

Potentially Real Cigarette Purchasing Tasks

Participants completed a series of computerized tasks where they were asked to purchase 7 days’ worth of their preferred brand of cigarettes under a series of price and income conditions. In each scenario (i.e., each individual purchasing question), participants were given an income and a price for cigarettes and asked to indicate how many cigarettes they would purchase for 1 week out of that income. For all income conditions, the prices assessed were $0.12, $0.25, $0.50, and $1.00 per cigarette. Note that in the area where the study was conducted, $0.25 per cigarette ($5.00 per pack) was similar to the market price for cigarettes in the community. Income conditions were assessed in a random order and prices within each income condition were assessed in an ascending order. Participants were told that after all purchasing scenarios were complete, one would be randomly selected as the “real” scenario. In this scenario, participants actually received the cigarettes purchased and any remaining balance left in their income account after the purchase. In reality, the $1.00 price in all income conditions was removed from this random selection procedure to prevent participants from receiving far fewer cigarettes than their typical amount consumed. Before the tasks, participants were read the following instructions:

You will now choose how many cigarettes you would buy at different prices to smoke for the next week. Please choose the actual number of cigarettes you would like to purchase to use over the next week based on the account balance shown at the top of the screen. Remember, one of your series responses will be chosen to come true at the end of the session and you will actually receive the total number of cigarettes you purchase during this task. In each scenario only choose the actual number of cigarettes you would purchase at each price, based on your current smoking habits. If a scenario is chosen to come true, you will receive the remaining balance of your account in the form of a personal check. You will be asked to only use cigarettes you purchase during this task for the next week, so please answer as if you cannot purchase any additional cigarettes outside of the study.

After 1 week, we contacted participants to ask them if they consumed any cigarettes outside those that they purchased in the lab and how many of the lab cigarettes they consumed that week. If they did not consume all of the cigarettes purchased in the lab, they were allowed to return them for a refund at the price paid. The mix of cigarettes and leftover income balance, along with a $5 payment for completing the 1-week follow-up questions, constituted the total participant compensation for the study.

Income Conditions

Four income conditions were included, with all four cigarette prices assessed at each (16 total purchasing scenarios). Two conditions were Set conditions where each participant received the same income, and two conditions were Relative conditions, in which each participant received an income that was related to his or her individual weekly cigarette consumption, as determined by a modified Timeline Follow-Back assessment.22 In the set high condition, all participants had an income of $280, which represents the amount of money required to purchase 40 cigarettes per day, enough to maintain baseline consumption at the maximum price point assessed in the study ($1.00) for a participant with the maximum daily usual cigarette consumption allowed in the study (40 per day). The set low condition was similar to set high condition, except the income was set to $70, representing the amount required to purchase 40 cigarettes per day at the “market” price point ($0.25). In the relative high and relative low conditions, the participant was provided with an income sufficient to maintain his or her own cigarette consumption level at a price of $1.00 and $0.25 per cigarette, respectively. In practice, the mean income in the relative high condition was $127 (SD = $42) and in the relative low condition was $32 (SD = $10). Two participants reported an average cigarette consumption of exactly 10 cigarettes per day, which yielded an income of $70 in both the relative high and set low conditions. These two participants were provided with fewer scenarios so that the $70 income condition was assessed only once.

Data Analysis

The number of cigarettes purchased was the dependent variable of interest in each of the purchasing scenarios. These data for each income condition were fit to the equation

| (1) |

were P is the cigarette price, Q is cigarette consumption at P price, Q 0 represents demand intensity (the level of consumption as P approaches 0), k is the span of the function between maximum and minimum consumption in log10 units, and a represents demand elasticity.10 The Q 0, a, and k parameters are free parameters, although the k parameter was fit as a common parameter across all income conditions (fitted k = 1.35), leaving only the Q 0 and a parameters varying among income conditions. These parameters were then individually compared across income conditions with nonlinear regression F tests in GraphPad Prism 6 (La Jolla, CA, USA). Following a significant F test, best-fit parameters associated with each income condition were considered significantly different from one another if the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of these parameter estimates did not overlap. We did not calculate Q 0 and a parameters for individual participants because there were only four prices assessed per income condition, leading to insufficient data to reliably fit an equation with two free parameters. P max, or the price that supported the most overall responding was also computed by taking the first derivative of Equation 1 and evaluating where it first crossed Y = −1 when incorporating the fitted parameters from each model. These values were then used to interpolate a P max with 95% confidence intervals in Prism 6, which were compared as described above.

Results

Cigarette Demand by Income Condition

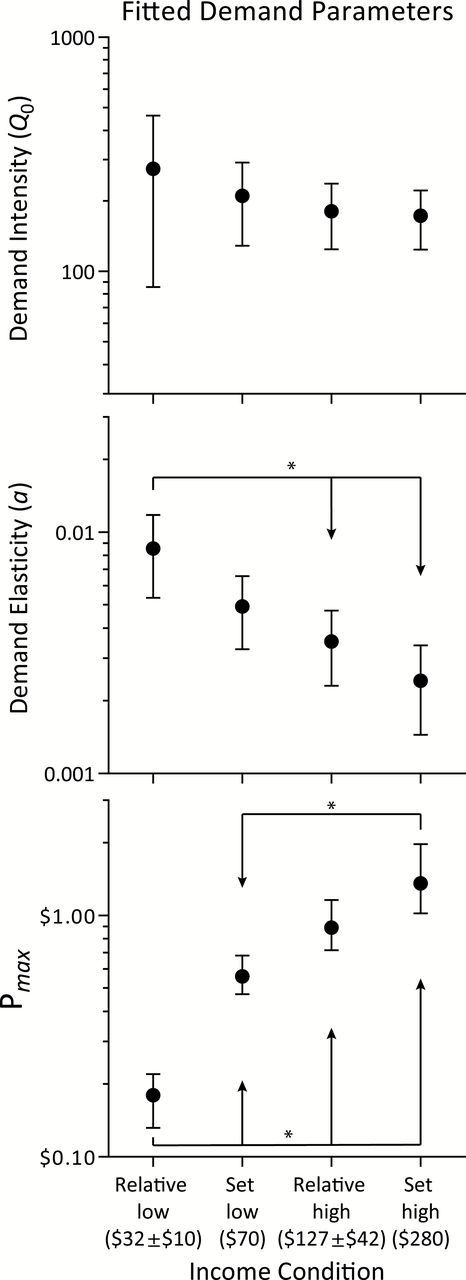

In general, the amount of cigarettes purchased in the purchasing scenarios was consistently related to both cigarette price and income condition. Increases in cigarette price and decreases in study income were both associated with decreases in cigarette purchases (Figure 1). These data obtained from the income and price scenarios was well described by Equation 1, with R 2 values for the fits to the mean data of 0.959 (set high), 0.993 (relative high), 0.985 (set low), and 0.995 (relative low). Reflecting the heterogeneous responses of the participants, R 2 values in the group model incorporating all participants together were 0.284 (set high), 0.437 (relative high), 0.610 (set low), and 0.600 (relative low). Demand analyses revealed that cigarette demand elasticity was significantly related to income condition (F 3,227 = 11.5, p < .001), but intensity was not (F 3,227 = 0.7, p = .7; see Figures 1 and 2). As study income increased, demand elasticity decreased. The best fit elasticity parameter (± 95% confidence interval) for the relative low condition was different from that from both the relative high and set high conditions (Figure 2). Similarly, P max, the price that supports the most overall expenditure, increased as a function of income condition from $0.18 (95% CI = $0.13–$0.22) per cigarette in the relative low condition to $0.56 (95% CI = $0.47–$0.68) in the set low condition, $0.89 (95% CI = $0.72–$1.16) in the relative high condition, and $1.36 (95% CI = $1.02–$1.98) in the Set High condition. The relative low P max differed from that in each of the other three conditions, and the set low and set high P max values were also different (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Mean (+ SEM) consumption of cigarettes at each of the 4 prices for each of the 4 income conditions.

Figure 2.

Fitted demand parameters (± 95% confidence interval) representing demand intensity (Q 0 from equation 1, top panel), demand elasticity (a from Equation 1, center panel), and P max (bottom panel) as a function of income condition. Demand elasticity and P max, but not demand intensity, was associated with income. *95% CI of parameters from indicated conditions do not overlap.

Adherence to Purchasing Conditions

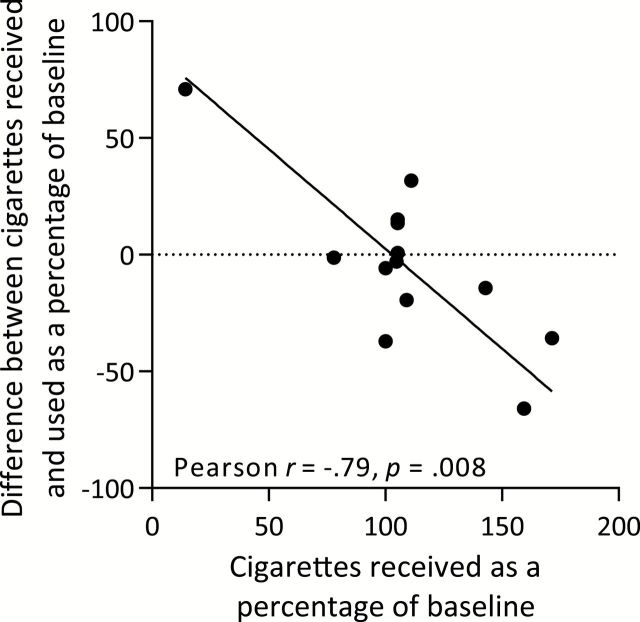

Using their study income, participants purchased the number of cigarettes in one of the income conditions and agreed to consume only those cigarettes purchased in the following week. After 1 week, participants were allowed to return any unconsumed cigarettes to receive the corresponding portion of their study income back, and they were asked to report how many cigarettes were consumed outside those provided. All 15 participants misattributed their actual cigarette consumption by at least one cigarette, with the highest misattribution being 149 cigarettes over the 1-week period. Nine participants reported using fewer cigarettes than they purchased, and six participants used cigarettes obtained outside the context of the study and smoked more cigarettes than they purchased. These misattributions were nonrandom and highly related to the number of cigarettes purchased in the purchase task (Figure 3). Participants who received more cigarettes than their typical consumption tended to return some of those excess cigarettes, while participants who received fewer cigarettes than their typical consumption were more likely to break study protocol and consume cigarettes obtained from other sources (r = −.79, p = .008).

Figure 3.

Cigarettes obtained in the chosen scenario for consumption in the following week expressed as a proportion of cigarettes typically consumed was negatively associated with the deviation in actual cigarettes consumed from the received amount. This indicates people who received more or fewer cigarettes than they tended to smoke on a regular basis either returned some cigarettes or smoked cigarettes obtained outside the study, respectively, producing study consumption amounts more closely aligned with their historical consumption.

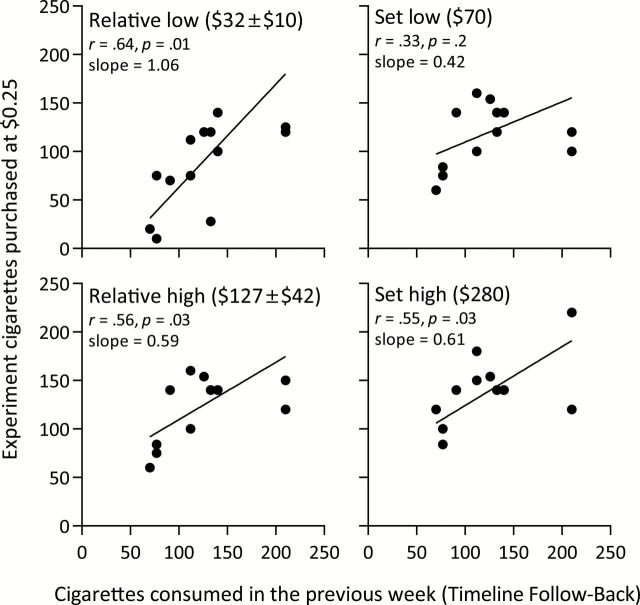

Correspondence Between Income Conditions and Recent Consumption

The number of cigarettes purchased in the potentially real purchasing scenarios at a price of $0.25 per cigarette (similar to the local price of cigarettes in the community) was compared to recent cigarette consumption as self-reported on the Timeline Follow-Back (Figure 4). The relative low income condition was most highly correlated with recent cigarette consumption (r = .64, p = .01), indicating the spread of consumption amounts in this condition was most reflective of actual cigarette consumption. Correlations were lower as income increased in the set low (r = .33, p = .2), relative high (r = .56, p = .03), and set high (r = .55, p = .03) conditions. Furthermore, the slope of the correlation in the relative low condition was very near 1.0, indicating that an increase in consumption in the purchasing scenario reflected a proportionate increase in real-world consumption of cigarettes. The slopes in the other three conditions were ≤0.61 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Correlations between cigarettes purchased at the $0.25 price (similar to the local price of cigarettes) in each income condition and number of self-reported cigarettes consumed in the week prior to study enrollment. The lowest income condition was most closely related to actual cigarette consumption.

Discussion

Smokers in this study making potentially real decisions about weekly cigarette purchases were affected by the amount of in-study income that was provided to them. Specifically, participants purchased more cigarettes when their income was greater, but only when the price of cigarettes was high. As price approached zero, purchases across the income conditions were not significantly different. This pattern of results was characterized by the significant decrease in demand elasticity and increase in P max as income increased, but no effect of income on demand intensity.

To the extent that in-study income influences behavior similarly as real-world income, these results indicate that the price sensitivity of individual smokers is related to their cigarette budget. Study incomes and cigarette prices were chosen to encompass a range that included an income that closely resembled the participant’s actual cigarette budget and the local market price for cigarettes (e.g., relative low condition at $0.25 per cigarette), income/price combinations that placed constraints on cigarette consumption (e.g., relative low and set low conditions at high cigarette prices), and study income high enough so that available budget was not a substantial constraint on purchasing patterns across the prices examined (e.g., set high condition), allowing us to examine the price/consumption relationship without budgetary restrictions forcing the consumption curve to adopt an elastic shape. Similar to other commodities, cigarette consumption is well-known to be influenced by cigarette price, with this relationship being well-described by Equation 1.10 This study shows a similarly orderly relationship between income and demand elasticity. This is similar to research on natural price changes in the economy2,3, but dissimilar to previous research with the hypothetical purchase task, which has shown no relationship between personal income and demand elasticity5, or an inverse relationship.8 Therefore, the manipulation of study income in the present potentially real purchase task may be a more representative model of actual changes in cigarette prices across income groups than examining indices of demand with the hypothetical purchase task across income groups. Further research should evaluate these relationships in greater detail.

If study income in this study is a model of actual income, taxes, and other regulations that increase cigarette cost would be more likely to influence the behavior of lower-income individuals. Similarly, the availability of cigarettes discounted in price (e.g., smuggled across political borders from a lower-tax region) would be more likely to increase consumption among lower-income individuals. At low income levels in a complete marketplace containing many nicotine product options, cigarette consumption may also switch to less expensive substitutes such as a nonpreferred brand of cigarettes to maintain levels of overall consumption.19 Furthermore, these results suggest that lowering the price of cigarettes has a similar, but not identical effect as increasing one’s income. Both manipulations result in greater consumption of cigarettes, but only when consumption is relatively constrained (i.e., high cigarette price and/or low income). These data suggest that public health interventions to reduce cigarette smoking that rely on effective increases in cigarette prices would only be effective on lower income individuals, and alternate approaches would be needed to affect the behavior of smokers with higher incomes.

The results of this study also have important implications for the measurement of real-world cigarette consumption in the laboratory. First, the in-study income provided to the participants had a large effect on the resulting cigarette demand elasticity, underscoring the importance of holding this variable constant or controlling for it across conditions. Second, we found that consumption in the lowest income condition was most related to self-reported cigarette consumption in the week prior to the experiment. This may be reflective of the relatively low income of most of the study participants, and indicates the importance of providing a study income that corresponds to the participants’ actual cigarette budget. Third, participants who received many more or many fewer cigarettes than the amount they typically consume tended to deviate from the study protocol and either consumed outside study cigarettes to make up for the deficit or returned excess study cigarettes during their 1-week follow-up. These deviations from the protocol may have implications for the accuracy of the hypothetical purchase task, or they may simply be a result of the open economy in which the study took place. If these deviations reflect a general lack of ability of the participants to accurately estimate the number of cigarettes they would consume under different price and income conditions, this suggests that data from the hypothetical purchase task is unreliable and not reflective of the actual relationship between consumption and price. Considering the orderly pattern of deviations from the purchase data, however, we do not believe this is the case. Instead it seems more likely that simply asking participants to agree to the rules of the experiment were not enough to compel them to do so, and participants instead participated in the open cigarette economy of the community throughout the consumption week.

As it is difficult to experimentally manipulate a participant’s actual income or the actual market price of cigarettes, it is not feasible to obtain analogous demand curves in a purely naturalistic environment, although natural experiments where cigarette prices were changed due to increased taxation indicate a clear price/consumption relationship similar to the one seen here.23–25 Furthermore, relationships between indices of demand and drug use level and dependence severity suggest these measures are useful clinically5–8 and the relationships found between price, consumption, and income in the current study are similar to those found by studies of actual cigarette consumption after natural changes in price due to taxes.1–3 This suggests the procedure used in this study and hypothetical purchase tasks in general are modeling what is observed in the actual economy, and may provide a platform for experimental manipulation of variables related to cigarette consumption. One could address some of the deviations from the purchasing agreement by conducting a similar hypothetically real purchase task experiment in a closed cigarette economy where outside purchases can be controlled, such as an inpatient hospital ward or a prison. Overall, these results suggest that convincing study participants to adhere to in-study cigarette purchases when they are in their natural environment is difficult and may require additional motivating factors to compel them, but despite this, results obtained from experiments such as these may model analogous relationships in the economy. It should be additionally noted that the relatively small sample size in this study was a limitation preventing us from obtaining reliable estimates of associations between indices of demand and participant characteristics such as personal income and dependence severity.

In conclusion, income is directly related to demand elasticity and P max, but not demand intensity. These results indicate that the amount of income that is available for cigarette purchases has a large effect on cigarette consumption, but only at high prices.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant U19 CA157345 to WKB. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. Gallet CA, List JA. Cigarette demand: A meta-analysis of elasticities. Health Econ. 2003;12:821–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hersch J. Gender, income levels, and the demand for cigarettes. J Risk Uncertainty. 2000;21:263–282. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Townsend J, Roderick P, Cooper J. Cigarette smoking by socioeconomic group, sex, and age: effects of price, income, and health publicity. BMJ. 1994;309:923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bickel WK, Green L, Vuchinich RE. Behavioral economics. J Exp Anal Behav. 1995;64:257–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. MacKillop J, Murphy JG, Ray LA, et al. Further validation of a cigarette purchase task for assessing the relative reinforcing efficacy of nicotine in college smokers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;16:57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. MacKillop J, Miranda R, Jr, Monti PM, et al. Alcohol demand, delayed reward discounting, and craving in relation to drinking and alcohol use disorders. J Abnormal Psychol. 2010;119:106–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. MacKillop J, Murphy JG, Tidey JW, et al. Latent structure of facets of alcohol reinforcement from a behavioral economic demand curve. Psychopharmacology. 2009;203:33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Tidey JW, Brazil LA, Colby SM. Validity of a demand curve measure of nicotine reinforcement with adolescent smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113:207–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hursh SR, Roma PG. Behavioral economics and empirical public policy. J Exp Anal Behav. 2013;99:98–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hursh SR, Silberberg A. Economic demand and essential value. Psychol Rev. 2008;115:186–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hursh SR, Winger G. Normalized demand for drugs and other reinforcers. J Exp Anal Behav. 1995;64:373–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. DeGrandpre RJ, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Higgins ST. Behavioral economics of drug self-administration. III. A reanalysis of the nicotine regulation hypothesis. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1992;108:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jacobs EA, Bickel WK. Modeling drug consumption in the clinic using simulation procedures: Demand for heroin and cigarettes in opioid-dependent outpatients. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;7:412–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Within-subject comparison of real and hypothetical money rewards in delay discounting. J Exp Analy Behav. 2002;77:129–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lagorio CH, Madden GJ. Delay discounting of real and hypothetical rewards III: Steady-state assessments, forced-choice trials, and all real rewards. Behav Process. 2005;69:173–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Madden GJ, Begotka AM, Raiff BM, Kastern LL. Delay discounting of real and hypothetical rewards. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;11:139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Madden GJ, Raiff BR, Lagorio CH, et al. Delay discounting of potentially real and hypothetical rewards: II. Between- and within-subject comparisons. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;12:251–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Amlung MT, Acker J, Stojek MK, Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Is talk ‘‘cheap’’? An initial investigation of the equivalence of alcohol purchase task performance for hypothetical and actual rewards. Alcohol. Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:716–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. DeGrandpre RJ, Bickel WK, Rizvi AT, Higgins ST. Effects on income on drug choice in humans. J Exp Anal Behav. 1993;59:483–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back. In Litten RZ, Allen JP (Eds.), Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992:41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hu TW, Sung HY, Keeler TE. Reducing cigarette consumption in California: tobacco taxes vs an anti-smoking media campaign. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1218–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Keeler TE. Taxation, regulation, and addiction: a demand function for cigarettes based on time-series evidence. J Health Econ. 1993;12:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Meier KJ, Licari MJ. The effect of cigarette taxes on cigarette consumption, 1955 through 1994. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1126–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]