Abstract

Introduction

Bloodstream infections are a major cause of death worldwide; blood culture (BC) sampling remains the most important tool for their diagnosis. Current data suggest that BC rates in German hospitals are considerably lower than recommended; this points to shortfalls in the application of microbiological analyses. Since early and appropriate BC diagnostics are associated with reduced case fatality rates and a shorter duration of antimicrobial therapy, a multicomponent study for the improvement of BC diagnostics was developed.

Methods and analysis

An electronic BC registry established for the German Federal state of Thuringia is the structural basis of this study. The registry includes individual patient data (microbiological results and clinical data) and institutional information for all clinically relevant positive BCs at the participating centres. First, classic result quality indicators for bloodstream infections (eg, sepsis rates) will be studied using Poisson regression models (adjusted for institutional characteristics) in order to derive relative ranks for feedback to clinical institutions. Second, a target value will be established for the process indicator BC rate. On the basis of this target value, recommendations will be made for a given combination of institutional characteristics as a reference for future use in quality control. An interventional study aiming at the improvement of BC rates will be conducted thereafter. On the basis of the results of a survey in the participating institutions, a targeted educational intervention will be developed. The success of the educational intervention will be measured by changes in the process indicator and the result indicators over time using a pre–post design.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics committee of the University Hospital Jena and from the Ethics committee of the State Chamber of Physicians of Thuringia. Findings of AlertsNet will be disseminated through public media releases and publications in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

DRKS00004825.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, INTENSIVE & CRITICAL CARE, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

AlertsNet is one of the first population-based surveillance studies for bloodstream infections worldwide and the first one within the German healthcare system.

The population-based approach in coordination with an extensive data collection strategy allows, for the first time, the establishment of institution-specific reference values for already existent and newly developed quality indicators which are crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of quality management tools.

By including an interventional study aiming at improving the diagnostic processes for bloodstream infections, AlertsNet evaluates directly its capability to provide a platform for quality improvement trials.

Since AlertsNet is voluntary for the participating institutions, it will be a challenge to keep adherence rates high so that a population-based interpretation of data will also be available in the long term.

Given its regional character, the results of AlertNet might not apply to other regions or healthcare systems; their transferability, however, can be estimated on the basis of the comparison of AlertsNet data with data from other regions in the world within the International Bacteremia Surveillance Collaborative.

Introduction

Bloodstream infections and the role of blood culture diagnostics

Bloodstream infections (BSI) and associated organ dysfunctions (defined as severe sepsis or septic shock) are a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1–5 With an annual incidence of 100/100 000 patient-days and a case fatality rate of 20–50%, BSI have been declared the third most common cause of death in Germany.6 Early diagnosis and adequate antibiotic treatment of BSI has been shown to be associated with a substantial reduction in mortality as well as in treatment costs.1 7 Blood cultures (BCs) are the most important diagnostic tool in the investigation of BSI as they allow the detection of causative pathogens.8–10 Early identification of the causative pathogen facilitates the improvement and shortening of antibiotic treatment and results in lower case fatality rates and reduced development of antibiotic resistance.

BC sampling rates (number of BC sets taken per 1000 inpatient days) have been reported to be considerably lower in Germany than in other European countries. The European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) report (ECDC) from 2011 showed a mean BC rate of 16.5/1000 inpatient days in the participating German hospitals.11 Within the German Hospital Infection Surveillance System (KISS), data from 223 intensive care units (ICUs) were collected and a mean BC rate of 60 sets per 1000 inpatient days was estimated.12 Since national and international guidelines recommend 100–200 BC sets per 1000 inpatient days, it appears that BCs are taken too rarely in German ICUs and hospitals in general.10 13 14 Moreover, positivity rates vary between institutions in Germany and are considerably lower than those obtained under controlled study conditions. This might indicate problems with respect to both the initiation and the performance of appropriate microbiological diagnostics.

Several national and international initiatives focus on capturing and reporting specific pathogens and antibiotic resistance rates obtained via BC diagnostics (eg, EARS-Net). However, these approaches provide limited data about diagnostic processes and affected patients, are not representative for the underlying population, and cannot be used directly to improve healthcare. Population-based surveillance has been recognised as an optimal means to define burden of disease, evaluate risk factors for acquiring infections, and monitor temporal trends in the occurrence and resistance of pathogens.15 Since all disease episodes occurring in a defined population at risk are included in this type of study, the potential for selection bias is minimised and calculation of unbiased incidence and mortality rates seems possible.16 To date, there are only a few population-based studies available which focus on BSI and which have declared collaboration within the International Bacteremia Surveillance Collaborative (IBSC).3–5 17 These studies report incidence rates which are considerably higher than those obtained via publicly available hospital discharge data,2 indicating that a population-based approach is necessary when aiming at an improvement of BSI management. Although the members of the IBSC have already published important research results from their surveillance networks,17 the results of these types of studies are not easily transferable to other countries; a study reflecting the pathogen and antibiotic resistance profiles in Germany as well as the properties of the German healthcare system will complement the available surveillance networks perfectly.

Quality indicators for BSI

Quality indicators are frequently used in healthcare when assessing potential shortcomings in diagnostic or therapeutic processes. Sepsis incidence rates, sepsis mortality rates, sepsis case fatality rates as well as rates of primary BSI have been named as potential quality indicators for the management of sepsis.18 However, all of these proposed indicators are result indicators and cannot be modified directly. Moreover, these measures are highly dependent on institutional characteristics as well as on coding guidelines. Since the definition of sepsis includes that BCs have been taken, available result indicators are also directly dependent on BC rates in the respective institutions.

In order to develop a set of candidate measures suitable as process indicators rather than result indicators for quality of sepsis care in ICUs, Berenholtz et al19 performed a systematic review followed by a panel discussion and identified 10 potential indicators. Of those suggested, only time to antibiotic treatment has been evaluated as a quality indicator in a large US study. However, it performed worse than expected since the time of defining the onset of sepsis has been considered to be very heterogeneous between different institutions.20

In addition to the list presented by Berenholtz et al, the proportion of cases in which <2 BC sets have been taken was suggested as a process quality indicator in the USA some years ago21 22; however, no follow-up studies or formal validation studies have been performed on this topic.

BC sampling rates are an interesting target for result indicator development, since they are a measure of diagnostic quality and can be modified directly. This indicator, however, has not yet been evaluated and validated.

Aims and objectives

AlertsNet is a prospective multicomponent study conducted in the German Federal State of Thuringia. The overall infrastructural goal of this study is the establishment of a BSI surveillance system for the whole federal state of Thuringia. On this basis, shortcomings within the diagnostic process in patients with BSI will be identified and improved using a multifactorial intervention concept. By enrolling all primary, secondary and tertiary care hospitals as well as eligible inpatient rehabilitation hospitals, AlertsNet will collect population-based data on BSI.

The primary objective of AlertsNet is the development of adjusted quality indicators for BSI taking into account appropriate and sufficient BC diagnostics. Individual performance with respect to the developed indicators can be reported to all institutions after a period of data collection and the development and validation of quality indicators, using a web-based reporting system; this allows for the participating institutions to respond quickly to the results and to improve potential shortcomings in the quality of their processes. The quality indicators established within the network will be used in an educational intervention study that aims at improving quality of care. An improvement of indicator variables would demonstrate that surveillance-based interventions can be an effective quality control measure to maximise quality of care.

Methods and analysis

Overall study design

The study is conducted in four phases. First, an electronic BC registry (EBCR) will be established. Second, individual data will be collected on all patients with positive BCs and matched with registry data. Quality indicators for BSI will be derived in a third step and validated using surveillance data generated in parallel. An interventional study aiming at improving the practice of diagnostics of BSI will be performed in the last step using routinely collected registry data as the outcome of interest.

EBCR and IT structure

Within the first funding period of AlertsNet, a unique EBCR is being established using microbiological routine data. The registry includes individual data (laboratory, clinical and demographic data) from all patients with clinically relevant positive BCs. BC results are transferred from microbiological laboratories to EBCR via a secured network. EBCR evaluates received microbiological findings according to a clinical relevance filter and sends a request for further data to the participating hospitals in case of relevant BC results. Participating hospitals submit clinical data into a web-based case report form, completely separated from EBCR. The whole process implements highest privacy and data protection standards.

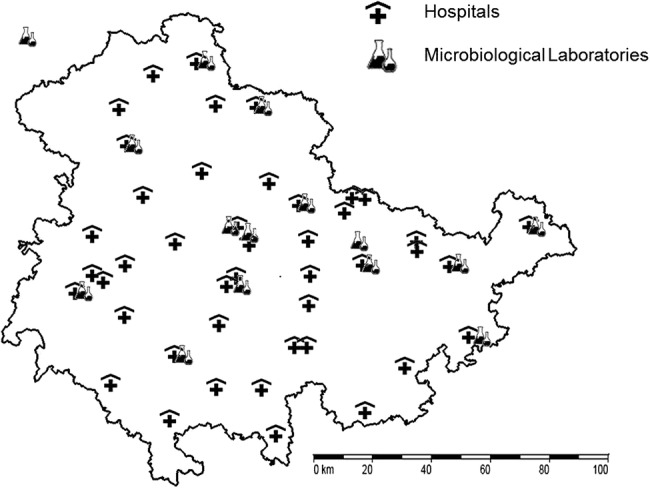

To date, 24 hospitals and 7 inpatient rehabilitation centres have signed contracts for commissioned data processing (orders for disclosure of data according to § 11 Federal Data Protection Act, BDSG), which already covers 75% of the eligible facilities in the federal state (figure 1). Negotiations with the remaining facilities have been started as it is the aim of AlertsNet to cover the entire population of Thuringia. The core facility of the registry is located at the Center for Sepsis Control and Care in Jena and will be collecting data via a secure statewide network system.

Figure 1.

Clinical and rehabilitation facilities and microbiological laboratories eligible for participation in AlertsNet. Hospitals which already signed contracts for commissioned data processing (acc. to § 11 Federal Data Protection Act, BDSG) in the first BMG funding period: Clinical Facilities: Robert-Koch-Krankenhaus Apolda, Klinikum Altenburger Land, Ilm-Kreis-Kliniken Arnstadt/Ilmenau, Zentralklinik Bad Berka, Klinikum Bad Salzungen, HELIOS-Kliniken Blankenhain/Bleicherode/Erfurt/Gotha/Meiningen, Katholisches Krankenhaus St. Johann Nepomuk Erfurt, Kreiskrankenhaus Greiz, Universitätsklinikum Jena, Eichsfeld-Klinikum Kleinbartloff, Hufeland Kliniken Mühlhausen/Bad Langensalza, Südharz-Krankenhaus Nordhausen, Thüringen-Kliniken “Georgius Agricola” Saalfeld, MEDINOS Kliniken Sonneberg/Neuhaus, Elisabeth-Klinikum Schmalkalden, Sophien- und Hufeland-Klinikum Weimar; Capio Klinik an der Weißenburg (Uhlstädt-Kirchhasel).

Preliminary (eg, derived from Gram stains) and final BC results are routinely communicated between microbiological laboratories and hospitals via secured networks. AlertsNet extends this setting by harvesting all final BC findings which are subsequently filtered by a defined algorithm for positivity and clinical relevance of depicted microbes.

Import of BC findings

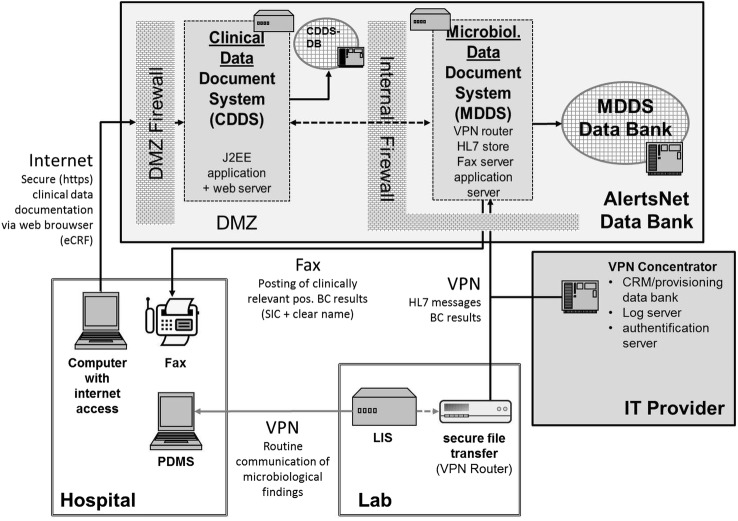

According to data privacy regulations, the IT structure (figure 2) implements specific concepts regarding the protection of data privacy, security and data economy. The AlertsNet system is divided into two main parts: the Microbiological Data Document System (MDDS) is connected to the laboratory information systems (LIS) of the laboratory via a virtual private network (VPN) located in a separate DMZ (perimeter network). Information on pathogens (with subtypes) and resistance patterns are obtained from the microbiological reports sent to the BC registry. The variable list transferred to the registry includes a number of items allowing calculations of transport times for different steps of laboratory analyses (see online supplementary appendix 1). Owing to the fact that common standards of implementation are lacking, individual parsing of transmitted data is required, that is, species names according to the ‘List of Prokaryotic Names with Standing in Nomenclature’ (LPSN, http://www.bacterio.net) and names of anti-infectives according to the European Pharmacopoeia (http://online.pheur.org). BC findings are transmitted as HL7 files, imported into the MDDS, and overwritten and deleted after generation of a subject identifier code (SIC). Each patient with positive BC findings is represented by an additional patient pseudonym, a hash generated from the first name, surname, and date of birth and sex, which enables the assignment of independent findings from different clinical facilities to the same patient without a clear name. The pseudonymisation process is designed to fulfil the requirements of the German Federal Office for Information Security (IT Baseline Protection Catalogue).

Figure 2.

AlertsNet IT structure established for the electronic blood culture registry. DB, Data Bank; DMZ, Demilitarized Zone; LIS, Laboratory Information System; PDMS, Patient Data Management System; VPN, Virtual Private Network.

Proposed sample size

According to the publicly reported Quality Reports of Thuringian hospitals from 2011, there are currently 22 244 hospital beds available for a total population of 2.2 million inhabitants. Excluding institutions with a low pretest probability for BSI (ie, psychiatry departments, hospital day units), a total number of 20 403 hospital beds or 7.5 million bed days per year are available for AlertsNet. Under the assumption of a BC sampling rate of 50 sets per 1000 bed-days (EARS report 2011; http://ecdc.europa.eu), 316 000 BC sets will be obtained in Thuringia per year. Given an assumed positivity rate of 8% and a contamination rate of 20%, 20 200 clinically relevant BC sets in about 5000 hospitalised patients are expected to be documented per year in the AlertsNet database (table 1).

Table 1.

Expected number of patients per year with clinically relevant positive blood culture (BC) results in the state of Thuringia

| Planned beds in Thuringia (total) | 22 244 |

| Planned beds with relevance for AlertsNet (active BC diagnostics) | 20 403 (92%) |

| Bed-days/year (×365) | 7 447 095 |

| Bed-days/ 1000 patients | 7 447 |

| ×85% (mean bed occupancy rate) | 6 330 |

| BC sets taken (about 50 BC sets per 1000 patient-days) | 316 501 |

| Positive BCs (×8% positivity rate) | 25 320 |

| True positive BCs (×80%, since 20% false positive) | 20 256 |

| Patients with true positive BCs (×25%, since a mean of 4 BC sets are taken per patient and episode) | 5 064 |

The numbers were estimated from data of planned beds from quality reports 2010 of the Thuringian BC processing facilities published by the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA).

Clinical data collection

If positive BC findings are defined as clinically relevant, an authorised clinical representative of the attending hospital that has obtained the BC will be contacted per personalised fax to conduct documentation of the patient's clinical data. The fax sheet contains the SIC and clear name to assign the respective patient. Clinical data will be recorded in the Clinical Data Document System (CDDS) which is accessible via https from the internet. The responsible documentation specialist completes an electronic case report form (eCRF) generated simultaneously with the fax sheet, which is only accessible via personalised login within 60 days after initiation of BC. During this period, fax reminders will be sent on a weekly basis. Patient data will be deleted immediately after documentation, but latest after a period of 60 days. From this point on, all data within AlertsNet will be fully anonymised.

Documentation of patient-related clinical data will be performed exclusively for clinically relevant positive BC results. Positive BCs collected in the registry undergo an automated algorithm aiming at differentiating contaminants from clinically relevant pathogens. For this, BC results are compared with predefined lists of obligate and facultative pathogenic bacteria. Obligate pathogens are automatically defined as clinically relevant at their first occurrence while facultative pathogenic bacteria must be cultured at least twice within 96 h in the same patient.10 Documentation will be performed for each new episode. A new episode is generated only if the same organism is cultured at least 96 h after the last positive BC in the same patient (for facultative pathogenic bacteria then again, 2 positive BCs within 96 h are necessary). In the case of a first or new episode, patient characteristics listed in online supplementary appendix 2 need to be documented. The variables include information on source and site of infection, risk factors, predispositions, antibiotic regimen and outcome. Moreover, transfers of the patient within and between hospitals will be covered. Both data sources (BC registry & eCRF) will be merged after 60 days and all information will be fully anonymised for data protection reasons.

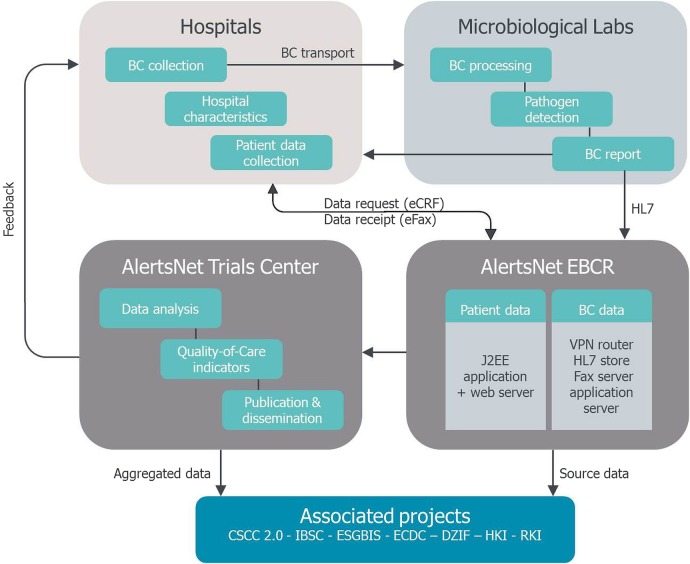

In addition to individual patient data and microbiological data, institutional variables are obtained from the participating centres including structural characteristics as well as current data on cases and procedures (see online supplementary appendix 3). Institutional data will be collected at hospital level as well as at department level. Since it could be shown that individual and institutional data complement each other in the circumstances of healthcare-associated infections,23 a multilevel data set covering all patients with a positive BC in Thuringia will be established and can be used for further investigation (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Data flow within the AlertsNet network. BC, blood culture; CSCC, Center for Sepsis Control and Care, Jena, Germany; DZIF, German Center for Infection Research; eCRF, electronic Case Report Form; ESGBIS, ESCMID (European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases) Study Group for Bloodstream Infections and Sepsis; HL7, Data communication standard; HKI, Hans-Knöll-Institut, Braunschweig, Germany; IBSC, International Bacteremia Surveillance Collaborative; RKI, Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany.

Development, validation and application of quality indicators

Within AlertsNet, quality indicators for the diagnosis and management of BSI will be derived at an institutional level and will be reported to the respective hospitals via web-based feedback for quality control. The evaluation of quality indicators, however, needs to take into account institution-specific characteristics as well as BC rates, since they have a considerable effect on the expected value of certain quality indicators such as the sepsis rate. Therefore, Poisson regression models adjusted for institutional characteristics will be used in order to evaluate result indicators such as BSI rates or case fatality rates. A backward elimination process based on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) will be used to identify institutional predictors of the outcome which need to be taken into account. Analyses will be based on data collected in a period of 12 months from all participating institutions. Recommendations for target values of the result indicators will be based on the expected values from the respective Poisson models for a given combination of institutional characteristics and adjusted for the institutional BC rate.

Reference values for the process indicator BC rate need to be derived in a different way. Since the form of association between the outcomes of interest (BSI rates and case fatality rates) and the process indicator BC rate is unknown, non-parametric regression models will be used in order to detect if there might be a saturation level for BC rates above which no further increase in the outcome can be observed (as suggested by a study based on data from German ICUs).14 This analysis needs to be conducted stratified for those institutional characteristics, which are associated with BSI rates or case fatality rates as the respective breaking points might differ dependent on a specific set of characteristics. The established breaking points will then be defined as the recommended BC rate target values for the institutions with the respective set of institutional characteristics and will also be reported via web-based feedback for quality control of those hospitals.

Since this study aims at collecting a comprehensive data set from all institutions and patients with BC diagnostics in the prespecified source population, sample size is determined a priori. Since all information will be available on a department level within each institution, about 150 units will be eligible for inclusion in this study. Assuming a participation rate of 70%, 105 units can be enrolled in AlertsNet. According to general recommendations on multivariable model building, in a sample with 100 units, models with up to 10 variables can provide stable estimates when used for the development of quality indicators.

Design of a pre–post interventional trial to improve BSI diagnostics

An interventional study aiming at improving the practice of BC diagnostics will be performed as a proof-of-principle after the establishment phase of AlertsNet has been successfully finished. Doctors and nurses of all participating institutions will be asked about their knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) with respect to BC diagnostics using a structured questionnaire that has already been developed and validated in the first phase of the study. On the basis of the results of this questionnaire as well as on the results of previous studies, a multifactorial intervention will be developed to improve the practice of BC diagnostics in the participating institutions.

Potential areas of improvement based on a systematic literature review are: (1) indication for BC, (2) puncture technique, (3) contamination-free performance, (4) blood volume per bottle, (5) the number of BC sets, (6) timing of BC withdrawal and (7) BC storage and transport. This intervention will be evaluated in a pre–post interventional trial.

The primary outcome of interest will be improvement of the process indicator ‘blood culture sampling rate’ in the respective institutions. Performance in quality indicators in the 6 months before intervention will be compared with the performance in the 6 months after intervention. A key secondary outcome will be knowledge, attitude and practice of the surveyed physicians and nurses. Here, a score for guideline adherence will be developed; the results of the KAP survey administered 6 months before intervention will be compared with results 6 weeks and 6 months after intervention.

In total, a sample size of 20 healthcare units will be sufficient to show a 30% improvement in BC rates with 80% power and a two-sided α of 5% (binomial test based on weighted probabilities for an individual BC test, 6 months preintervention and postintervention as the study period, and 45 BC sets per unit and year). The units participating in this trial will be selected randomly from those participating in AlertsNet.

Future prospects

AlertsNet will evaluate, for the first time, a population-based surveillance programme for BSI within the German healthcare system. The established network and registry system will allow researchers to investigate the effectiveness of intervention programmes in a well-defined environment with standardised outcome measures. A major strength of the project is the state wide data collection, which enables population-based estimates. Most research on diagnostic and therapeutic strategies of sepsis focuses only on ICUs, since septic patients often need ICU treatment due to the severity of their disease. However, about 50% of all sepsis cases arise in low-risk environments, including standard wards as well as rehabilitation hospitals.24 This also includes community-onset BSI which can be differentiated in AlertsNet from hospital-onset BSI using the eCRF system; thus, retrospective data about the time before admission to the hospital can be gathered. This is important as there is only limited knowledge on diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in these patients with BSI before they are transferred to an ICU. AlertsNet is already associated with the IBSC and will become an IBSC partner once the BC registry is fully established. By being part of this multinational surveillance network, AlertsNet can contribute to research on inter-regional differences in incidence, risk factors, outcomes and resistance rates. Moreover, AlertsNet will be part of a surveillance region that spans several countries in different parts of the world and thereby includes a surveillance population of many million people; this will allow the study of rare isolates and facilitate the early detection of emerging organisms.

The major challenge for the future of AlertsNet will be to keep adherence rates of institutions in Thuringia high so that a population-based interpretation of data will also be available in the long term. Moreover, monitoring the epidemiology of BSI in a healthcare region requires that all laboratories within this region submit data on BSI to the monitoring programme. Barriers to this include rapidly changing providers of laboratory services (public vs private laboratories), legal constraints and incompatibility of information systems.25 If AlertsNet is not successful in maintaining a population-based data collection (equal to covering more than 90% of all BSI cases in Thuringia), this needs to be addressed in the analysis and interpretation stage. Moreover, data quality in the participating hospitals will be constantly evaluated and weekly reports will be sent back to the institutions. Regular audits will be implemented in addition for the participating laboratories and clinical institutions.

Once the feasibility of the proposed concept can be demonstrated within this study, the concept will be available for a wider roll-out in Germany and for other countries with comparable healthcare systems. Thus, AlertsNet can provide an evidence-based concept for an institution-specific quality management of BSI.

Ethics and dissemination

The project protocol and the technical IT concept were reviewed and approved by the independent data protection officer of the University Hospital Jena (April 2013) and by the Thuringian State Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (TLfDI) (Erfurt, Germany; April 2015). No individual informed consent will be sought due to the applied data collection plan, anonymisation strategy and analysis concept of the study.

Findings of AlertsNet will be disseminated through public media releases and publications in peer-reviewed journals, so that scientists, public health authorities and patients can get access to study results suitable for their level of expertise. Moreover, AlertsNet is represented by a website (http://www.alertsnet.de), which offers up-to-date study information for all kind of providers and patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: FMB, RTM, RPS, AK, SC, ST and FR contributed to study concept and design. AK and RTM contributed to drafting of the manuscript. RPS, SC, FR, MJ and FMB contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: AlertsNet is currently funded by the German Ministry of Health (BMG, grant IIA5-2512FSB114) and by the Thuringian Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs, Health, Women and Family (TMASGFF) for the so-called establishment phase of AlertsNet. In 2015, the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) has announced to sustain funding until July 2020 with an incremental financial contribution attendance by the TMASGFF starting in 2018. The project is furthermore supported by the Paul-Martini-Sepsis Research Group (funded by the Thuringian Ministry of Education, Science and Culture (ProExcellence; grant PE 108-2)), the publicly funded Thuringian Foundation for Technology, Innovation and Research (STIFT), the German Sepsis Society (GSS) and the Jena Center of Sepsis Control and Care (CSCC, funded by the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; grant 01 EO 1002)). The Paul-Martini Sepsis Research Group has been supported by unrestricted grants of BD Diagnostics, Heidelberg, Germany

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics committee of the University Hospital Jena (No. 3744-05/13) and by Ethics committee of the State Chamber of Physicians of Thuringia (Jena-Maua, Germany; February 2014).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: As this is a study protocol of a not yet performed study, no data have yet been obtained and no data sharing statement can be made at this point.

References

- 1.Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE et al. . Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med 2006;34:1589–96. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217961.75225.E9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laupland KB, Gregson DB, Flemons WW et al. . Burden of community-onset bloodstream infection: a population-based assessment. Epidemiol Infect 2007;135:1037–42. 10.1017/S0950268806007631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madsen KM, Schonheyder HC, Kristensen B et al. . Secular trends in incidence and mortality of bacteraemia in a Danish county 1981–1994. APMIS 1999;107:346–52. 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1999.tb01563.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skogberg K, Lyytikainen O, Ruutu P et al. . Increase in bloodstream infections in Finland, 1995–2002. Epidemiol Infect 2008;136:108–14. 10.1017/S0950268807008138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uslan DZ, Crane SJ, Steckelberg JM et al. . Age- and sex-associated trends in bloodstream infection: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:834–9. 10.1001/archinte.167.8.834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engel C, Brunkhorst FM, Bone HG et al. . Epidemiology of sepsis in Germany: results from a national prospective multicenter study. Intensive Care Med 2007;33:606–18. 10.1007/s00134-006-0517-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puskarich MA, Trzeciak S, Shapiro NI et al. . Association between timing of antibiotic administration and mortality from septic shock in patients treated with a quantitative resuscitation protocol. Crit Care Med 2011;39:2066–71. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31821e87ab [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall KK, Lyman JA. Updated review of blood culture contamination. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006;19:788–802. 10.1128/CMR.00062-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S et al. . The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1546–54. 10.1056/NEJMoa022139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seifert H, Abele-Horn M, Fätkenheuer G et al. . Blutkulturdiagnostik: sepsis, endokarditis, katheterinfektionen. In: (DGHM) DGfHuM, ed. Mikrobiologisch-infektiologische Qualitätsstandards (MiQ). Elsevier, 2007:74–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe 2011. Annual Report of the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net). Stockholm:ECDC, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gastmeier P, Schwab F, Behnke M et al. . [Less blood culture samples: less infections?]. Anaesthesist 2011;60:902–7. 10.1007/s00101-011-1889-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baron EJ, Weinstein MP, Dunne WM Jr et al. . Blood cultures IV. In: Baron EJ, ed. Cumitech—cumulative techniques and procedures in clinical microbiology. ASM Press, 2005:24–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karch A, Castell S, Schwab F et al. . Proposing an empirically justified reference threshold for blood culture sampling rates in intensive care units. J Clin Microbiol 2015;53: 648–52. 10.1128/JCM.02944-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laupland KB. Defining the epidemiology of bloodstream infections: the ‘gold standard’ of population-based assessment. Epidemiol Infect 2013;141:2149–57. 10.1017/S0950268812002725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaynes R. Surveillance of antibiotic resistance: learning to live with bias. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1995;16:623–6. 10.2307/30141112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laupland KB, Schonheyder HC, Kennedy KJ et al. . Rationale for and protocol of a multi-national population-based bacteremia surveillance collaborative. BMC Res Notes 2009;2:146 10.1186/1756-0500-2-146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun BI, Kritchevsky SB, Kusek L et al. . Comparing bloodstream infection rates: the effect of indicator specifications in the evaluation of processes and indicators in infection control (EPIC) study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2006;27:14–22. 10.1086/498966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berenholtz SM, Pronovost PJ, Ngo K et al. . Developing quality measures for sepsis care in the ICU. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2007;33:559–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venkatesh AK, Avula U, Bartimus H et al. . Time to antibiotics for septic shock: evaluating a proposed performance measure. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:680–3. 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schifman RB, Bachner P, Howanitz PJ. Blood culture quality improvement: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study involving 909 institutions and 289 572 blood culture sets. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1996;120:999–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schifman RB, Strand CL, Braun E et al. . Solitary blood cultures as a quality assurance indicator. Qual Assur Util Rev 1991;6:132–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kritchevsky SB, Braun BI, Kusek L et al. . The impact of hospital practice on central venous catheter associated bloodstream infection rates at the patient and unit level: a multicenter study. Am J Med Qual 2008;23:24–38. 10.1177/1062860607310918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heublein S, Hartmann M, Hagel S et al. . Epidemiologie der Sepsis in deutschen Krankenhäusern—eine Analyse administrativer Daten. INTENSIV-News 2013;17(4/13). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sogaard M, Lyytikainen O, Laupland KB et al. . Monitoring the epidemiology of bloodstream infections: aims, methods and importance. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2013;11:1281–90. 10.1586/14787210.2013.856262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]