Abstract

Objective

The current study aimed to better understand trends and risk factors associated with non-fatal drowning of infants and children in the USA using two large, national databases.

Methods

A secondary data analysis was conducted using the National Inpatient Sample and the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample databases. The analytic sample (n=19 403) included children <21 years of age who had a diagnosis code for near-drowning/non-fatal drowning. Descriptive, χ2 and analysis of variance techniques were applied, and incidence rates were calculated per 100 000 population.

Results

Non-fatal drowning incidence has remained relatively stable from 2006 to 2011. In general, the highest rates of non-fatal drowning occurred in swimming pools and in children from racial/ethnic minorities. However, when compared with non-Hispanic Caucasian children, children from racial/ethnic minorities were more likely to drown in natural waterways than in swimming pools. Despite the overall lower rate of non-fatal drowning among non-Hispanic Caucasian children, the highest rate of all non-fatal drowning was for non-Hispanic Caucasian children aged 0–4 years in swimming pools. Children who were admitted to inpatient facilities were younger, male and came from families with lower incomes.

Conclusions

Data from two large US national databases show lack of progress in preventing and reducing non-fatal drowning admissions from 2006 to 2011. Discrepancies are seen in the location of drowning events and demographic characteristics. New policies and interventions are needed, and tailoring approaches by age and race/ethnicity may improve their effectiveness.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

New information is presented that describes trends and characteristics of non-fatal drowning in the USA between 2006 and 2011 from the National Inpatient Sample and the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample databases.

Children of racial/ethnic minorities have more than four times the rate of non-fatal drowning than Caucasian children in the USA.

Males and younger children are more likely to be admitted to inpatient facilities, suggesting greater insult from the submersion event.

The study used retrospective data available from large national data sets in the USA. We were not able to differentiate between public and private pools, and limited data were available around the circumstances of the submersion event. Additionally, due to the de-identification of the data, we could not distinguish among children who may have been in both data sets. Last, the study reports only data from the USA.

Unintentional, non-fatal drowning of children: US trends and racial/ethnic disparities.

Introduction

Drowning is a serious public health problem worldwide.1 In the USA, 10 deaths due to drowning are reported every day, with one of every five deaths being a child under 15 years of age.2 Drowning is the second leading cause of accidental death in children.2 For each drowning victim in the USA, it has been estimated that five children go to the hospital for non-fatal drowning submersion events;2 however, the incidence of non-fatal drowning may be underestimated, as some children may be seen in primary care offices and urgent care facilities, and there is no systematic reporting mechanism for non-fatal drowning as there is for fatal drowning. In a recent study from Australia, non-fatal drowning rates are rising.3 In that study, the authors reported that, on average, there were three child or adolescent fatal drowning events per week in Queensland, with an additional 10 non-fatal drowning events for every fatality.3 Non-fatal drowning may have serious long-term consequences due to hypoxia and subsequent brain damage.4–6 Although the mortality and morbidity of drowning and non-fatal drowning is known to be a public health problem, and 85% of drowning events are preventable,6 preventive interventions have not been effective in lowering the incidence.1 7 Patterns of fatal drowning have been described, and risk factors, such as location of drowning, age, gender and race/ethnicity have been identified.8 9 By contrast, less is known about non-fatal drowning. Pearn et al,10 in 1979, and Quan et al,11 in 1989, each reported on both fatal and non-fatal drowning events in children from one US county. Race/ethnicity data were not reported in either study. Cohen et al,12 in 2008, reported 2003 data on a representative sample of children who were admitted to US hospitals for submersion-related injuries. Again, no race/ethnicity data are reported, and only children who were admitted to a hospital are included.12 Recently, Wallis et al3 reported on both fatal and non-fatal drowning in a population study of children in Queensland, Australia. Data were reported by age and gender. Since the prevalence of non-fatal drowning is at least five times that of fatal drowning, it is important to determine if there are similar risk factors for each, by age and location of submersion event in US children.2 Additionally, children from racial/ethnic minority groups in the USA are at greater risk for numerous health-related disparities,13–19 including fatal drowning.9 A clearer picture of the risk for non-fatal drowning by race/ethnicity, in addition to age and location of event for US children is needed. In order to develop and target effective interventions, more data are needed to understand the patterns of non-fatal drowning events. For example, it has been shown that males, younger children and children from racial/ethnic minorities are at greater risk of fatal drowning, and the distribution varies across different locations (pools, natural waterways, etc).9 However, characteristics of children at greatest risk for non-fatal drowning in a representative, national, US sample have not been shown. The current study aimed to identify risk factors associated with non-fatal drowning of infants and children in the USA using two large, national databases and to describe the frequency with which these children were seen in an emergency department (ED) when compared against inpatient settings.

Methods

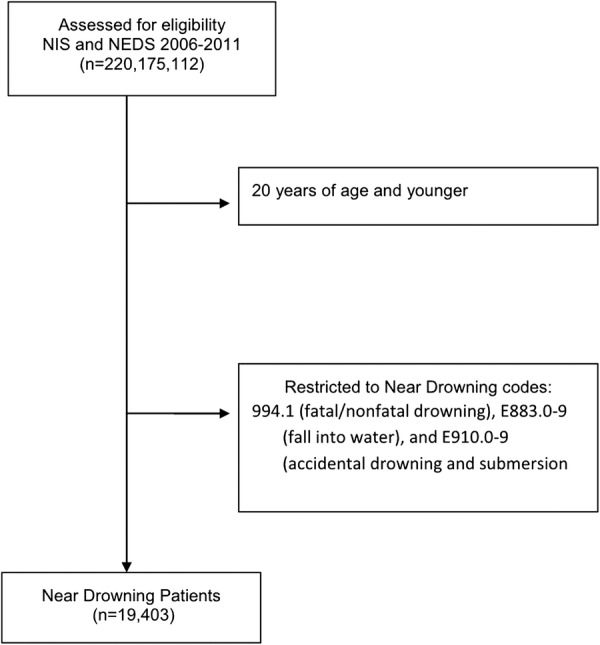

Data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) and the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) were used (figure 1).20 21 The NIS is the largest, publicly available, all-payer, inpatient care database in the USA, and it contains data from approximately eight million hospital stays each year (a 20% stratified sample of US community hospitals).20 The sampling methodology aims to capture a representative sample of all US community hospital discharges, which come from the State Inpatient Databases and includes >95% of the target universe. The strata used in creating the NIS are US division, urban or rural location, teaching status, ownership and bed size. The NIS sample unit is a systematic random sample of discharges stratified by hospital characteristics. The sample includes approximately 20% of discharges from US community hospitals.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram to develop analytic sample (NEDS, Nationwide Emergency Department Sample; NIS, National Inpatient Sample).

The NEDS is the largest all-payer ED database in the USA, containing data from approximately 30 million discharges from emergency medicine facilities each year.21 The NEDS is a stratified sample of US hospitals. The target universe for the NEDS is all US community hospital-based EDs. The NEDS includes data on care that began in the ED regardless of whether the patient was treated and released or admitted to the hospital. Hospitals used in the NEDS database are categorised according to five strata. These strata include geographic region, location, teaching status, ownership and trauma-level designation. A 20% stratified random sample of US hospital-based EDs is then selected. Once the hospitals have been selected, 100% of all visits to the ED from the selected hospitals are included in the NEDS. This type of sampling design is referred to as a stratified, single-stage, cluster sample.

Since NEDS data are currently only available from 2006 to 2011, data from both the NIS and NEDS from 2006 to 2011 were used in the current study. The analytic sample consisted of individuals who were (1) 20 years of age and younger and (2) had an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) or E code for non-fatal drowning: 994.1 (fatal/nonfatal drowning), E883.0–9 (fall into water) and E910.0–9 (accidental drowning and submersion).

No direct patient identifiers are available in these publicly available data sets. The university's Institutional Review Board determined that the study was not considered human subjects research, and was, therefore, exempt. In addition, a Data Use Agreement was signed when the data sets were obtained.

Statistical analysis

Using descriptive analyses, we examined the distribution of non-fatal drowning by demographic factors over time for children <21 years of age. Additionally, we explored the frequency of children being managed in the ED compared with inpatient hospitalisation, and whether the incidence of drowning had changed over time.

Demographic data collected included age, gender, race/ethnicity and insurance status. Drowning circumstances data recorded sites of non-fatal drowning. To test for differences in age between the three groups (pools, natural waterways vs other sites), analysis of variance techniques were used, while χ2 techniques were used to test for differences among categorical variables. The ‘other’ non-fatal drowning sites included, for example, falling into a well, falling into a storm drain, and falling into some other kind of water-logged hole. The total incidence of non-fatal drowning was stratified by location where medical treatment was received (ED vs inpatient). The overall non-fatal drowning incidence rate was calculated per 100 000 population (using 2006–2011 Census data),22 and a χ2 test was performed to compare annual incidences. In these final analyses, comparisons were made for children of ages 0–4, 5–9, 10–14 and 15–19 years, because of the groupings used with the US Census data. This allowed the calculation of incidence rates per 100 000 children in the population, which also allows comparison with previously published research.

Results

Risk factors

As seen in table 1, there were n=19 403 non-fatal drowning episodes in the analytic sample, with a majority of non-fatal drowning occurring at a swimming pool (n=12 754, 65.7%). Table 1 presents the percentage of non-fatal drowning by age, gender and race/ethnicity across three types of locations (pools, natural waterways and others). Children who experienced non-fatal drowning in pools were younger than children who experienced non-fatal drowning in other settings (9.6 years vs 14.4 years and 10.2 years, p<0.001). Likewise, children who were non-Hispanic Caucasians (12.1% vs 5.9% and 8.2%, p<0.001) and had private insurance (35.1% vs 17.1% and 10.1%, p<0.001), more frequently experienced non-fatal drowning in pools compared with natural waterways or other places. Children experiencing a non-fatal drowning, overall, are more likely to be male (78%). The distribution of males by location of non-fatal drowning varied as follows: natural waterways (82.4%), pools (78.1%) and others 63.9% (p<0.001). Table 2 presents the percentages and ORs for the demographic characteristics for various locations of non-fatal drowning (pools, natural waterways and others).

Table 1.

Demographics of children who experience a non-fatal drowning, unadjusted

| Variable | Total non-fatal drowning N=19 403 |

Pools N=12 754 (65.7%) |

Natural waterways N=5045 (26.0%) |

Other N=1604 (8.3%) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 10.9 (11.7) | 9.6 (10.2) | 14.4 (11.8) | 10.2 (13.1) | <0.001** |

| Male (%) | 15 143 (78.0) | 9961 (78.1) | 4157 (82.4) | 1025 (63.9) | <0.001** |

| Race (%) | <0.001** | ||||

| Caucasian | 1973 (10.2) | 1543 (12.1) | 298 (5.9) | 132 (8.2) | |

| African-American | 5894 (30.4) | 3928 (30.8) | 1483 (29.4) | 483 (30.1) | |

| Hispanic | 8690 (44.8) | 5318 (41.7) | 2669 (52.9) | 703 (43.8) | |

| Other | 2846 (14.7) | 1964 (15.4) | 595 (11.8) | 287 (17.9) | |

| Insurance (%) | <0.001** | ||||

| Public | 12 806 (66.0) | 7742 (60.7) | 3930 (77.9) | 1134 (70.7) | |

| Private | 5502 (28.4) | 4477 (35.1) | 863 (17.1) | 162 (10.1) | |

| Other | 1096 (5.7) | 536 (4.2) | 252 (5.0) | 308 (19.2) |

Table 2.

Comparison of raw number of non-fatal drowning events by location and demographic characteristics of victim

| Site of non-fatal drowning | Groups | Number of non-fatal drowning/total number | Percentage | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pools | Caucasian | 1543/1973 | 78.2 | Ref | |

| African-American | 3928/5894 | 66.6 | 0.56 (0.49 to 0.63) | <0.001** | |

| Hispanic | 5318/8690 | 61.2 | 0.44 (0.39 to 0.49) | <0.001** | |

| Other | 1964/2846 | 69.0 | 0.62 (0.54 to 0.71) | <0.001** | |

| Privately Insured | 4477/5502 | 81.4 | Ref | <0.001** | |

| Publicly Insured | 7742/12 806 | 60.5 | 0.35 (0.32 to 0.38) | <0.001** | |

| Other | 536/1096 | 48.9 | 0.22 (0.19 to 0.25) | ||

| Female | 2793/4260 | 65.6 | Ref | ||

| Male | 9961/15 143 | 65.8 | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.08) | 0.793 | |

| Natural waterways | Caucasian | 298/1973 | 15.1 | Ref | |

| African-American | 1483/5894 | 25.2 | 1.89 (1.65 to 2.17) | <0.001** | |

| Hispanic | 2669/8690 | 30.7 | 2.49 (2.18 to 2.84) | <0.001** | |

| Other | 595/2846 | 20.9 | 1.49 (1.28 to 1.73) | <0.001** | |

| Privately Insured | 863/5502 | 15.7 | Ref | ||

| Publicly Insured | 3930/12 806 | 30.7 | 2.38 (2.19 to 2.58) | <0.001** | |

| Other | 252/1096 | 23.0 | 1.60 (1.37 to 1.88) | <0.001** | |

| Female | 888/4260 | 20.8 | Ref | ||

| Male | 4157/15 143 | 27.5 | 1.44 (1.32 to 1.56) | <0.001** | |

| Others | Caucasian | 132/1973 | 6.7 | Ref | |

| African-American | 483/5894 | 8.2 | 1.24 (1.02 to 1.52) | 0.031** | |

| Hispanic | 703/8690 | 8.1 | 1.23 (1.01 to 1.49) | 0.037** | |

| Other | 287/2846 | 10.1 | 1.56 (1.26 to 1.94) | <0.001** | |

| Privately insured | 162/5502 | 2.9 | Ref | ||

| Publicly insured | 1134/12 806 | 8.9 | 3.20 (2.71 to 3.79) | <0.001** | |

| Others | 308/1096 | 28.1 | 12.88 (10.50 to 15.81) | <0.001** | |

| Female | 579/4260 | 13.6 | Ref | ||

| Male | 1025/15 143 | 6.8 | 0.46 (0.41 to 0.51) | <0.001** |

Inpatient compared with ED

Table 3 shows the comparison between children seen in the ED compared with those admitted to inpatient facilities by demographic characteristics. Almost 91% of children admitted to an inpatient facility were male compared with 71.7% of the children seen in the ED (p=0.002). On average, children admitted to an inpatient facility were 5.6 years of age (SD =2.9), while children seen in the ED were 13.5 years (SD= 6.2, p<0.001). A higher percentage of children seen in the ED had private insurance and greater family income (p<0.001) compared with those admitted to an inpatient facility. As would be expected, the costs were higher for those admitted to an inpatient facility (US$6372, SD= US$15 K), compared with those being seen in the ED (US$4528, SD= US$12 K, p<0.001).

Table 3.

Comparison of demographics and disposition between those managed in the emergency department (ED) and inpatient

| Variable | ED N=16 085 |

Inpatient N=3318 |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 13.5±6.2 | 5.6±2.9 | <0.001** |

| Privately insured (%) | 5260 (32.7) | 654 (19.7) | <0.001** |

| Higher income (3rd and 4th quartiles) (%) | 9168 (57.0) | 1185 (35.7) | <0.001** |

| Discharged (%) | <0.001** | ||

| Home | 15 136 (94.1) | 2897 (87.3) | |

| Home health | 290 (1.8) | 90 (2.7) | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 0 (0.0) | 202 (6.1) | |

| Transferred out | 338 (2.1) | 83 (2.5) | |

| Other | 322 (2.0) | 46 (1.4) | |

| Male (%) | 11 533 (71.7) | 3013 (90.8) | 0.002** |

| Costs | US$4528±US$12K | US$6372±US$15K | <0.001** |

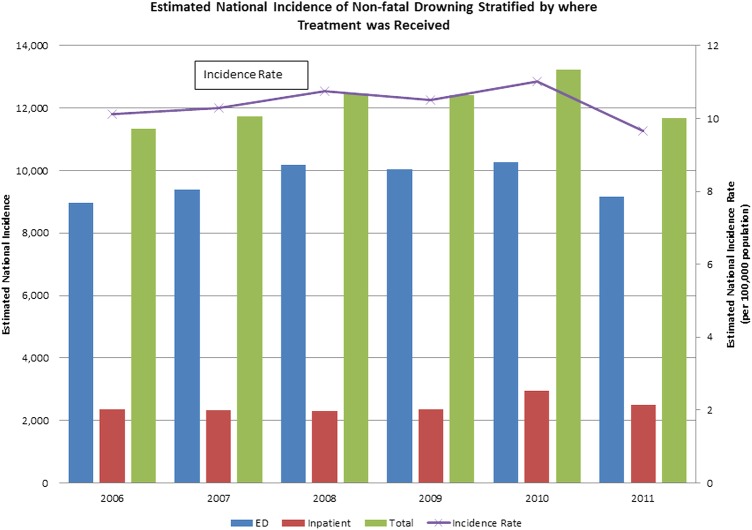

Trend over time

The incidence rate (figure 2) was consistent over time (2006–2011) with roughly 10 non-fatal drowning events annually per 100 000 population (χ2 for trend p=0.712). A majority of the children having a non-fatal drowning are managed in the ED (roughly two-thirds), with 8000–9000 children being managed in the ED each year (χ2 for trend p=0.623). The remaining 3000–4000 children managed for non-fatal drowning are admitted to an inpatient setting and this has also remained consistent over time (χ2 for trend p=0.894).

Figure 2.

Incidence of non-fatal drowning over time: overall and stratified by inpatient or emergency department admission.

Racial disparities

Last, to better appreciate the racial and ethnic differences that lead to long-term health disparities, we adjusted the non-fatal drowning data by the population size of children in the USA in order to make comparisons across age, race/ethnicity and location (table 4). When all locations for non-fatal drowning are combined, Caucasian children had a lower rate of non-fatal drowning (4.3/100 000 children vs 17.7, 16.9 and 16.7/100 000 children). Non-Caucasian children are roughly four times more likely to have a non-fatal drowning. These results held consistent across all age groups (0–4, 5–9, 10–14 and 15–19 years).

Table 4.

Non-fatal drowning by demographics, adjusted by population from US census data

| Setting | Rate per 100 K children by age group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–4 years | 5–9 years | 10–14 years | 15–19 years | Total | |

| All settings | |||||

| Caucasian | 6.8 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 4.3 |

| African-American | 28.1 | 15.7 | 14.0 | 12.9 | 17.7 |

| Hispanic | 26.9 | 15.1 | 13.3 | 12.3 | 16.9 |

| Other | 26.6 | 14.9 | 13.2 | 12.2 | 16.7 |

| Total | 16.1 | 9.0 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 10.1 |

| Pools | |||||

| Caucasian | 45.6 | 25.6 | 22.7 | 20.9 | 28.7 |

| African-American | 25.6 | 14.3 | 12.7 | 11.7 | 16.1 |

| Hispanic | 20.0 | 11.2 | 10.0 | 9.2 | 12.6 |

| Other | 28.3 | 15.8 | 14.1 | 12.9 | 17.8 |

| Total | 26.1 | 14.6 | 13.0 | 11.9 | 18.8 |

| Natural waterways | |||||

| Caucasian | 6.9 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 4.6 |

| African-American | 13.4 | 7.6 | 7.0 | 6.7 | 8.7 |

| Hispanic | 17.7 | 10.0 | 9.2 | 8.7 | 11.4 |

| Other | 10.4 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 6.8 |

| Total | 13.8 | 7.8 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 7.9 |

| Other | |||||

| Caucasian | 3.0 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 2.0 |

| African-American | 3.7 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.5 |

| Hispanic | 3.6 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.4 |

| Other | 4.6 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 3.1 |

| Total | 3.7 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 |

| Total for Age Group | 15.7 | 8.8 | 7.8 | 7.2 | 10.1 |

Age disparities

The youngest children (aged 0–4 years) had the highest non-fatal drowning rate of 16.1/100 000, with the rate monotonically decreasing across the other age groups (9.0, 7.9 and 7.4/100 000 for children aged 5–9, 10–14 and 15–19 years, respectively).

Location-racial disparities

The only location in which Caucasian children had the highest rates of non-fatal drowning was in pools (28.7/100 000 vs 16.1, 12.6 and 17.8/100 000). Despite overall and many individual rates of non-fatal drowning being lower in Caucasian children, the highest rate of non-fatal drowning (45.6/100 000) occurs in Caucasian children under the age of 4 years in swimming pools. While relatively lower compared with Caucasian children, all races/ethnicities had a higher rate of non-fatal drowning events in swimming pools compared with other locations (African-American= 25.6, Hispanic= 20.0 and others= 28.3) for children aged 0–4 years.

Children aged 0–4 years experienced non-fatal drowning in natural waterways at the following rates: Hispanic= 17.7, African-American= 13.4, others= 10.4 and non-Hispanic Caucasians= 6.9). The lowest rates of non-fatal drowning for all ages and races/ethnicities occurred in ‘other’ locations (0–4 years= 3.7, 5–9 years= 2.2, 10–14 years= 2.0 and 15–19 years= 2.0).

Discussion

Fatal and non-fatal drownings are serious concerns for children, resulting in death or potentially long-term negative consequences. The current study provides new information that describes trends and characteristics of non-fatal drowning in the USA between 2006 and 2011, from the NEDS and NIS databases. These data add to what is already known about fatal drowning in the USA and non-fatal drowning in US counties and states, as well as in Australia. Together, this information informs the development of new interventions to reduce the rates of both fatal and non-fatal drowning.

Like fatal drowning, the highest rates of non-fatal drowning events occur in children 0–4 years of age, and in males. Non-fatal drowning most commonly occurs in swimming pools for children of all ages, and the next most common location for such events is in natural waterways. These findings differ from fatal drowning, in that, fatal drowning rates are higher in pools than natural waterways in children 0–4 and 5–9 years of age, while natural waterways are higher for children 10–14 and 15–19 years of age.9 Across all ages and locations, children from racial/ethnic minorities (Hispanic, African-American and others) have more than four times the rate of non-fatal drowning than children who are Caucasian. However, children who are Caucasian are more likely to have a non-fatal drowning event in a pool at all ages than any other racial/ethnic group in our sample. Similarly, those with private insurance have lower rates of non-fatal drowning than children with public insurance, thereby suggesting that low-income families are at greater risk. Additionally, males and younger children, in general, are more likely to be admitted to an inpatient facility, thus suggesting that they are more likely to experience a submersion event of greater severity. However, there were no significant differences between children discharged from the ED and those discharged for inpatient hospitals on disposition on discharge. Ninety-four per cent of the children seen in the ED and 87% of those who were admitted to inpatient hospitals were discharged home, which was not significantly different. From these data, it cannot be determined if the two groups differed on severity of insult or long-term morbidity, or if the younger children were admitted as a precautionary measure. The more frequent admission of males to inpatient facilities seems more likely to be associated with the presence of more severe symptoms as there would be no clear rationale to suggest that precaution was more warranted for males than females.

Males have been shown to be at greater risk than females for both non-fatal and fatal drowning events.3 10–12 However, the rates for males in the current study far exceed those previously reported. Similarly, Quan et al in 1989 reported non-fatal drowning rates by age adjusted by 100 000 population in King County, Washington, USA, as 12.1 (0–4 years), 2.2 (5.9 years), 1.4 (10–14 years) and 0.1 (15–19 years), compared with our rates of 15.7 (0–4 years), 8.8 (5–9 years), 7.8 (10–14 years) and 7.2 (15–19 years). Data from Australia reported in 2015 for data collected during 2002–2008, indicate that in Queensland, Australia, the rates of non-fatal drowning events are much higher in children aged 0–4 years than we reported in the current study, but lower at all other ages.3 Non-fatal drowning events occurred in children aged 0–4 years at a rate of 39.85/100 000 compared against 15.7/100 000 in the current study.3 Other differences were more modest with rates of 5.59, 4.22 and 6.01 for ages 5–9, 10–14 and 15–19,3 respectively, compared against 8.8 (5–9 years), 7.8 (10–14 years) and 7.2 (15–19 years) in the current study. In the only other US national sample, Cohen et al12 reported on only those children admitted to hospitals, and reports rates much lower than those found in the current study in each age group. Inclusion of ED visits improves the estimate, but our study still probably underestimates the rates since we cannot account for children seen in other outpatient settings or who were not seen by a healthcare provider.

Over 16 000 children were seen in the ED, and 3318 were admitted to an inpatient facility following non-fatal drowning. On average, the cost for the ED visit was US$4500 compared with US$6400 for a hospital stay. The majority of the children were discharged to home, but some required home health, skilled nursing care, or transfers to other hospitals. These data suggest that the personal and fiscal costs of non-fatal drowning are substantial. While the vast majority of fatal and non-fatal drowning events are preventable,6 our data suggest that non-fatal drowning has remained stable from 2006 to 2011.

Evidence supports several strategies to reduce drowning deaths,23 24 but the data suggest that current public health interventions, policies or other strategies are not resulting in reduced drowning mortality or morbidity.3 23 25 More research is needed to better understand factors that will increase effectiveness of strategies to reduce both fatal and non-fatal drowning. Some suggestions include prevention of alcohol use in youth,24 increased availability of swimming lessons,24 26 increased use of fencing around swimming pools,23 24 more education of parents regarding the need for constant supervision of children near water,23 24 26 27 and raising public awareness of the need for administration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation within 5 min of a drowning event.6 23 In a recent systematic review of interventions associated with drowning prevention, Wallis et al found that only a few studies exist that use rigorous study designs and have high levels of empirical evidence. However, despite the relative lack of evidence, there is some support that education, pool fencing and swimming and water safety programmes are effective. More data are needed on these and other strategies, such as training in the provision of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and wearing personal flotation devices.28

While education is important, knowledge alone has been shown to be necessary, though insufficient, to change health promotion behaviours.29 Recent data have shown that parents underestimate the age at which it is safe to allow children to be unattended while bathing,30 underestimate the supervision needs of children in relation to swimming,26 and overestimate children's swimming skills.26 31 In one study, parents reported the best age to teach swimming to children was at ages 2 (42%), 3 (37%), 4 (18%) and >5 (8%) years.31 In the same study, 32% of the parents believed that it was better to teach toddlers to swim rather than increase parental supervision.31 Targeting messages to specific groups of parents to change knowledge, attitudes and beliefs may be helpful, but data are needed to develop evidence-based messages and methods of delivery. In one study, water safety messages were given in writing to all parents visiting the ED for any reason.32 Only 50% of the parents, who remembered having been given written discharge instructions, remembered the water safety messages.32 Parents reported that they found the messages helpful, and 41% remembered, unaided, that they received a message about life jackets, 25% about drowning risk and 13% about swimming.32 No data were available on family or child demographics, or whether there was any change in parenting behaviour as a result of these messages.

Future measures to reduce drowning or near-drowning should target interventions by taking into account the age, race/ethnicity or other salient characteristics of the children at increased risk. Additional data are needed to better understand what programmes and policies are needed to remove barriers to the use of strategies that have demonstrated effectiveness.

Although our study provides new information about non-fatal drowning, there are limitations. The study used retrospective data available from a large national data set. We were not able to differentiate between public and private pools, and limited data were available around the circumstances of the submersion event. One may argue that in order to develop targeted interventions, we need to discern whether varying incidences of non-fatal drowning among demographic subgroups are attributable to differences of exposure (eg, more likely to be in water for recreation), or some other phenomena subsequent to exposure (eg, less likely to use personal flotation devices). The retrospective nature of the data, and granularity of the information were not sufficient to discriminate these types of factors. Additionally, due to the de-identification of the data, we could not distinguish among children who may have been in both data sets. A further limitation is that we can only report those non-fatal drowning events that presented to the hospitals (EDs or inpatient facilities) that are in the sampling frame as described in the methods. Non-fatal drowning events that presented to primary care or other non-hospital settings were not included. Last, no data were available to control for length of stay in the ED or in the inpatient facility. Assumptions cannot be tested regarding severity of illness based on admission to hospital compared with ED treatment only. However, we did find that children who were admitted to the hospital were significantly younger than those who were treated and released from the ED. It cannot be determined if that represented greater severity of illness or greater caution in treating younger children.

Fatal and non-fatal drowning of children is a major public health concern. More awareness is needed around this issue, since 85% of drowning events are preventable,6 but little progress has been made over the past decade. Although the data are from 1997, one study showed that in a sample of paediatricians in the USA (n= 560), the majority did not counsel their patients or their patients’ parents on drowning prevention.33 It is important that paediatricians and other healthcare providers take advantage of opportunities to provide anticipatory guidance that safeguards child patients, as well as advocate for community approaches that increase safety in relation to prevention of drowning. Further research is needed to determine the most effective interventions, such as methods for delivering prevention messages, keeping in mind that the interventions should be targeted for specific risk factors or subpopulations that are more endangered.

Footnotes

Contributors: HF, DWD, JM and GL developed the study design and contributed to the interpretation of the data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. JM conducted the data analyses. DWD and JM drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final submission.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global report on drowning: preventing a leading killer. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Department for Management of NCDS, Disability, Violence and Injury Prevention, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Unintentional drowning: get the facts. Secondary unintentional drowning: get the facts 24 October 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/water-safety/waterinjuries-factsheet.html

- 3.Wallis BA, Watt K, Franklin RC et al. Drowning mortality and morbidity rates in children and adolescents 0–19 yrs: a population-based study in Queensland, Australia. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0117948 10.1371/journal.pone.0117948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lord SR, Davis PR. Drowning, near-drowning and immersion syndrome. J R Army Med Corps 2005;151:250–5. 10.1136/jramc-151-04-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moon RE, Long RJ. Drowning and near-drowning. Emerg Med 2002;14:377–86. 10.1046/j.1442-2026.2002.00379.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szpilman D, Bierens JJLM, Handley AJ et al. Drowning. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2102–10. 10.1056/NEJMra1013317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawson KA, Duzinski SV, Wheeler T et al. Teaching safety at a summer camp: evaluation of a water safety curriculum in an urban community setting. Health Promot Pract 2012;13:835–41. 10.1177/1524839911399428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai D, Zhang Y, Lynch CA et al. Childhood drowning in Georgia: a geographic information system analysis. Appl Geogr 2013;37:11–22. 10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.10.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilchrist J, Parker EM. Racial/ethnic disparities in fatal unintentional drowning among persons aged <29 years: United States, 1999–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:421–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearn JH, Wong RY, Brown J III et al. Drowning and near-drowning involving children: a five-year total population study from the City and County of Honolulu. Am J Public Health 1979;69:450–4. 10.2105/AJPH.69.5.450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quan L, Gore EJ, Wentz K et al. Ten-year study of pediatric drownings and near-drownings in King County, Washington: lessons in injury prevention. Pediatrics 1989;83:1035–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen RH, Matter KC, Sinclair SA et al. Unintentional pediatric submersion-injury-related hospitalizations in the United States, 2003. Inj Prev 2008;14:131–5. 10.1136/ip.2007.016998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood JN, Hall M, Schilling S et al. Disparities in the evaluation and diagnosis of abuse among infants with traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics 2010;126:408–14. 10.1542/peds.2010-0031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hogue CJ. Environmental health disparities in children. Rev Environ Health 2011;26:139–40. 10.1515/reveh.2011.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang KY, Calzada E, Cheng S et al. Physical and mental health disparities among young children of Asian immigrants. J Pediatr 2012;160:331–36.e1. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iriart C, Handal AJ, Boursaw B et al. Chronic malnutrition among overweight Hispanic children: understanding health disparities. J Immigr Minor Health 2011;13:1069–75. 10.1007/s10903-011-9464-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mollborn S, Lawrence E, James-Hawkins L et al. How resource dynamics explain accumulating developmental and health disparities for teen parents’ children. Demography 2014;51:1199–224. 10.1007/s13524-014-0301-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park C, Tan X, Patel IB et al. Racial health disparities among special health care needs children with mental disorders: do medical homes cater to their needs?. J Prim Care Community Health 2014;5:253–62. 10.1177/2150131914539814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright K, Suro Z. Using community-academic partnerships and a comprehensive school-based program to decrease health disparities in activity in school-aged children. J Prev Intervent Community 2014;42:125–39. 10.1080/10852352.2014.881185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP NIS Database Documentation. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Secondary HCUP NIS Database Documentation. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) July 2014. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdbdocumentation.jsp

- 21.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP NEDS Database Documentation. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Secondary HCUP NEDS Database Documentation. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) December 2014. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/neds/nedsdbdocumentation.jsp

- 22.United States Census Bureau. American Fact Finder. Secondary American Fact Finder 2010. http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/searchresults.xhtml?refresh=t

- 23.Bugeja L, Franklin RC. An analysis of stratagems to reduce drowning deaths of young children in private swimming pools and spas in Victoria, Australia. Int J Inj Control Saf Promot 2013;20:282–94. 10.1080/17457300.2012.717086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schyllander J, Janson S, Nyberg C et al. Case analyses of all children's drowning deaths occurring in Sweden 1998–2007. Scand J Public Health 2013;41:174–9. 10.1177/1403494812471156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suominen PK, Vähätalo R, Sintonen H et al. Health-related quality of life after a drowning incident as a child. Resuscitation 2011;82:1318–22. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrongiello BA, Sandomierski M, Schwebel DC et al. Are parents just treading water? The impact of participation in swim lessons on parents’ judgments of children's drowning risk, swimming ability, and supervision needs. Accid Anal Prev 2013;50:1169–75. 10.1016/j.aap.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee LK, Thompson KM. Parental survey of beliefs and practices about bathing and water safety and their children: Guidance for drowning prevention. Accid Anal Prev 2007;39:58–62. 10.1016/j.aap.2006.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallis BA, Watt K, Franklin RC et al. Interventions associated with drowning prevention in children and adolescents: Systematic literature review. Inj Prev 2015;21:195–204. 10.1136/injuryprev-2014-041216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Decis Mak Process 1991;50:179–211. 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porter TR, Crane LA, Dickinson LM et al. Parent opinions about the appropriate ages at which adult supervision is unnecessary for bathing, street crossing, and bicycling. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007;161:656–62. 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moran K, Stanley T. Parental perceptions of toddler water safety, swimming ability and swimming lessons. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot 2006;13:139–43. 10.1080/17457300500373572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quan L, Bennett E, Cummings P et al. Do parents value drowning prevention information at discharge from the emergency department? Ann Emerg Med 2001;37:382–5. 10.1067/mem.2001.114091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Flaherty JE, Pirie PL. Prevention of pediatric drowning and near-drowning: a survey of members of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics 1997;99:169–74. 10.1542/peds.99.2.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]