Abstract

Objectives

Obesity is suggested to be a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis (OA). This meta-analysis aimed to examine the relationship between body mass index (BMI) and the risk of knee OA in published prospective studies.

Design

Meta-analysis.

Studies reviewed

An extensive literature review was performed, and relevant studies published in English were retrieved from the computerised databases MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane.

Methods

The effect estimate (RR or HR) and its 95% CI are investigated on the basis of the evaluation of differences of knee OR risk in overweight or obesity versus those with normal weight. Category-specific risk estimates were further transformed into estimates of the RR in terms of per increase of 5 in BMI by using the generalised least-squares method for trend estimation. Studies were independently reviewed by two investigators. Subgroup analysis was performed. Heterogeneity and publication bias were assessed. Data from eligible studies were extracted, and the meta-analysis was performed by using the STATA software V.12.0.

Results

14 studies were finally included in the analysis. The results showed that overweight and obesity were significantly associated with higher knee OA risks of 2.45 (95% CI 1.88 to 3.20, p<0.001) and 4.55 (95% CI 2.90 to 7.13, p<0.001), respectively. The risk of knee OA increases by 35% (95% CI 1.18 to 1.53, p<0.001) with a 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI. Subgroup analysis showed that obesity was an independent predictor of knee OA risk regardless of the study country, sample size, gender proportion of participants, duration of follow-up, presence of adjusted knee injury and assessed study quality above or below an NOS score of 8. No publication bias was detected.

Conclusions

Obesity was a robust risk factor for knee OA. Professionals should take a possible weight reduction into account for the treatment of knee OA whenever a patient is significantly overweight.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We applied random-effect models based on the heterogeneity of the true effects distribution, which avoided the bias of overstating the precision of findings in fixed-effects models.

A limitation of the current study was the small number of studies involved, with limited numbers of participants. This reflected the paucity of high-quality clinical trials that addressed this research topic.

We conclude that all patients with osteoarthritis should be treated with caution. There is still a considerable need for more high-quality studies assessing adiposity using parameters on body mass index only.

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA), which is a degenerative disease, is the most common form of arthritis in the knee.1 Knee OA is related to ageing, articular cartilage obesity, fatigue, trauma, joint congenital abnormalities and joint deformities caused by many factors such as degradation of injury, under joint margins and subchondral bone reactive hyperplasia.2 Clinical manifestations of knee OA are slow development of joint pain, tenderness, stiffness, joint swelling, limited mobility and joint deformities. There were 20 million individuals suffering from knee OA in the USA, and this figure is expected to double over the next two decades.3 4 Knee pain was reported by up to a half of the individuals aged over 50, among which severe and disabling knee pain accounted for approximately 50%.5 The high prevalence and substantial impact on quality of life of knee OA calls for more high-quality research in this area.

The prevalence of obesity has been growing alarmingly in the world, concurrently with increasing predisposition to multiple comorbidities.6 Being overweight is a key factor for knee OA,7 8 and provides substantial grounds for concern of disease severity and medical costs from treatment and productivity losses.9 In a cohort study of 1420 participants, Felson reported that obese individuals have 1.5 to 2 times the risk of developing knee OA as their leaner counterparts.10 Fowler-Brown found that a 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI was associated with a 32% increase in the probability of OA, and leptin contributed approximately half of the total effect of obesity on knee OA.7 Within a meta-analysis of risk factors for the onset of knee OA, obesity (OR=2.63, 95% CI 2.28 to 3.05) was found to be associated with knee OA. However, although this meta-analysis included both cohort and case–control studies, data on subgroup analysis were not available.11

This study systematically combined existing prospective studies that investigated the association of obesity and risk of knee OA to identify the true effect sizes. This study used a random-effect meta-analysis following the MOOSE guidelines12 for observational studies and the QUORUM guidelines for clinical trials.13

Materials and methods

Search strategy for identifying studies

An in-depth literature search was performed using the keywords ‘obesity’ OR ‘weight’ OR ‘body weight’ OR ‘body mass’ OR ‘body mass index’ OR ‘anthropometric’ OR ‘anthropometry’ OR ‘adiposity’ AND (‘arthritis’ OR ‘osteoarthritis’ OR ‘OA)’ in various combinations. The computerised databases PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane were searched to identify eligible studies in English-language journals before August 2014. We also searched the relevant references in the retrieved studies and reviewed articles from the bibliographic database. The corresponding authors in some studies were contacted for more information beyond that in their published articles.

Article selection criteria

All prospective studies that explored the association of obesity and risk of knee OA were considered eligible for the analysis. Two investigators (Zheng Huaqing and Chen Changhong) independently assessed the articles for relevance. Articles that met the following criteria were excluded: (1) cross-sectional studies; (2) a standardised effect size could not be calculated. (3) BMI were categorised according to the WHO (normal weight: BMI of less than 25.0 kg/m2; overweight: 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 of BMI; obese: over 30.0 kg/m2 of BMI) or Asian criteria (normal weight: BMI of less than 23.0 kg/m2; overweight: 23.0–24.9 kg/m2 of BMI; obese: over 25.0 kg/m2 of BMI) of the elderly.14 It was because this meta-analysis was performed mainly using the data from published studies that the need for institutional review board approval was waived.

Quality assessment and data abstraction

The Newcastle-Ottawa-Scale (NOS)15 was used to assess the quality of each article. The NOS contains eight items, categorised into three dimensions including selection, comparability and, depending on the study type, outcome (cohort studies). For each item, a series of response options was provided. A star system was used to allow a semiquantitative assessment of study quality, such that the highest quality studies were awarded a maximum of one star for each item with the exception of the item related to comparability that allowed the assignment of two stars. The NOS ranges between zero and nine stars.

All articles were first de-identified (article title, author names, journal name and year of publication) before selection. The abstracts of the articles were independently reviewed by two of the authors (Zheng Huaqing and Chen Changhong). The data were filtered and input into a standard electronic form. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion until a consensus was reached. If there was no consensus, the principal investigator (Zheng Huaqing) would make the final decision on the eligibility of the study and data extraction.

Statistical analyses

Data management and analysis were performed by using the STATA software (V.12.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). We examined the relationship between BMI and the risk of knee OA on the basis of the effect estimate (RR or HR) and its 95% CI published in each study. A random-effects model was used to calculate summary RRs and 95% CIs for overweight or obesity compared to normal weight individuals. We then transformed category-specific risk estimates into estimates of the RR associated with every 5 kg/m2 increase in body mass index (BMI) by using the generalised least-squares method for trend estimation. These estimates were calculated assuming the presence of a linear relationship between the natural logarithm of the RR and increasing BMI. The value assigned to each BMI category was the midpoint for closed categories and the median for open categories (assuming a normal distribution for BMI). We combined the RRs for each 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI by using a random-effect meta-analysis.

The measure of heterogeneity was evaluated by using I2, which was used to assess the percentage of the total variation from all studies to define the heterogeneity. A high value for I2 indicates heterogeneity. I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% correspond to cut-off points for low, moderate and high degrees of heterogeneity. Publication bias was evaluated by using Egger’s test in this statistical analysis. Funnel plots for the incidence of knee OA were visually inspected.16

Subgroup analyses were conducted to investigate the impact of the study country, sample size, gender proportion of participants, duration of follow-up, presence of adjusted knee injury and assessed study quality above or below an NOS score of 8 on the pooled effect sizes. We also performed a sensitivity analysis by removing each individual study from the meta-analysis in order to study the influence on the meta-analysis of each study. All reported p values were 2-sided, and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant for all included studies.

Results

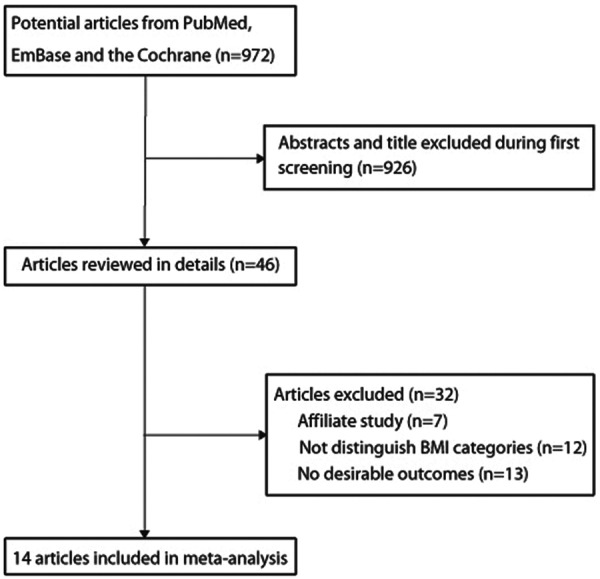

A total of 972 abstracts were initially selected through database search and citation tracking, and 926 articles were excluded because they failed to meet the criteria. For the remaining 46 articles, 7 were affiliate study, 12 did not have comparison data of different BMI groups and 13 had no desirable outcomes to calculate effect sizes. The results of the study-selection process are shown in figure 1. In addition, the baseline characteristics and NOS score of the 14 articles8 17–29 selected for our analysis are shown in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart describing the article selection process. BMI, body mass index.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis

| Study | Country | Study design | Sample size | Age at baseline | Percentage male | Knee OA cases | Follow-up (year) | Covariates in fully adjusted model | NOS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grotle et al17 | Norway | Cohort | 1854 | 24–76 | 43.7% | 114 | 10.0 | Age, gender, work type, leisure time activities | 7 |

| Hart et al18 | UK | Cohort | 715 | 54.1 | 0 | 95 | 4.0 | Hysterectomy, ERT, smoking, physical activity, knee pain and social class | 6 |

| Cooper et al19 | UK | Cohort | 346 | >55.0 | 26.3 | 45 | 5.1 | Age and sex | 7 |

| Reijman et al20 | Netherlands | Cohort | 1372 | >55.0 | – | 75 | 6.6 | Age, sex and follow-up time | 8 |

| Järvholm et al21 | Sweden | Cohort | 320 192 | 15–67 | 100% | 502 | 12.0 | Age and smoking | 8 |

| Niu et al22 | USA | Cohort | 2623 | 62.4 | 40% | 163 | 2.5 | Age, gender, race, bone mineral density and knee injury | 7 |

| Liu et al23 | UK | Cohort | 490 532 | 50–69 | 0 | 974 | 2.9 | Age, region of recruitment, deprivation index | 8 |

| Wang et al24 | Australia | Cohort | 41 528 | 25–75 | 41.1% | 541 | 5.0 | Age, gender, country of birth and education | 8 |

| Toivanen et al25 | Finland | Cohort | 823 | >30 | 44.8% | 94 | 22.0 | Age, gender | 9 |

| Lohmander et al8 | Sweden | Cohort | 27 960 | 45–73 | 39.4% | 471 | 11.0 | Age, gender, smoking and physical activity | 9 |

| Felson et al26 | USA | Cohort | 598 | 63.7 | 36.3% | 93 | 8.0 | Age, gender, smoking, physical activity, knee injury and weight change | 7 |

| Hochberg et al27 | USA | Cohort | 437 | >20 | 68.2% | – | 4.0 | Age, gender and smoking | 6 |

| Manninen et al28 | Finland | Cohort | 6647 | 40–64 | – | 126 | 10.0 | None | 7 |

| Shiozaki et al29 | Japan | Cohort | 1191 | 40–65 | 0 | – | 14.0 | Physical exercise and knee injury | 7 |

ERT, estrogen replacement therapy; NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa-Scale; OA, osteoarthritis.

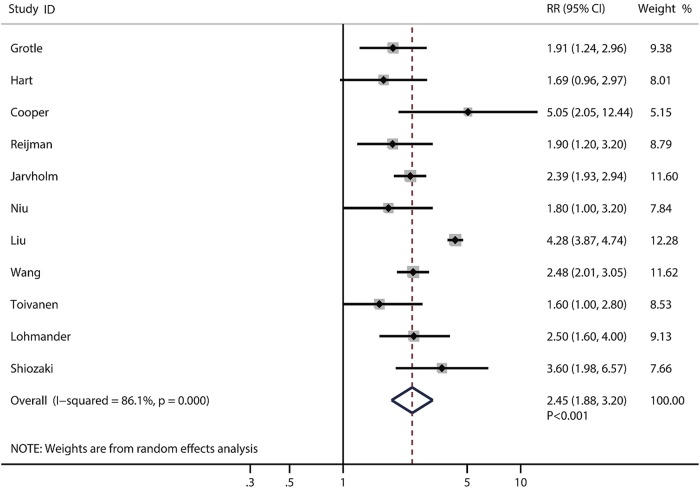

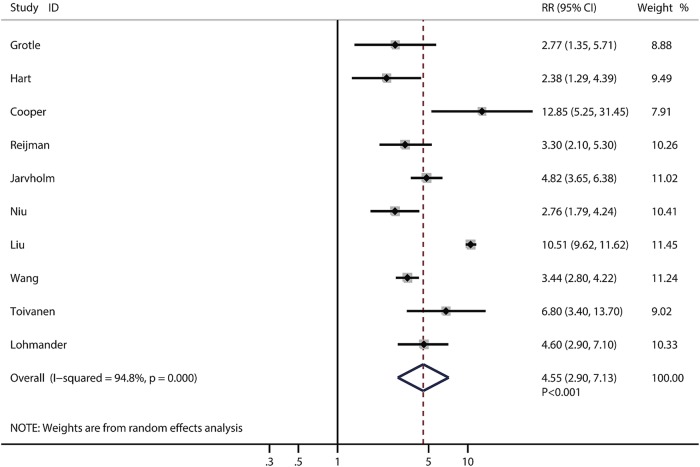

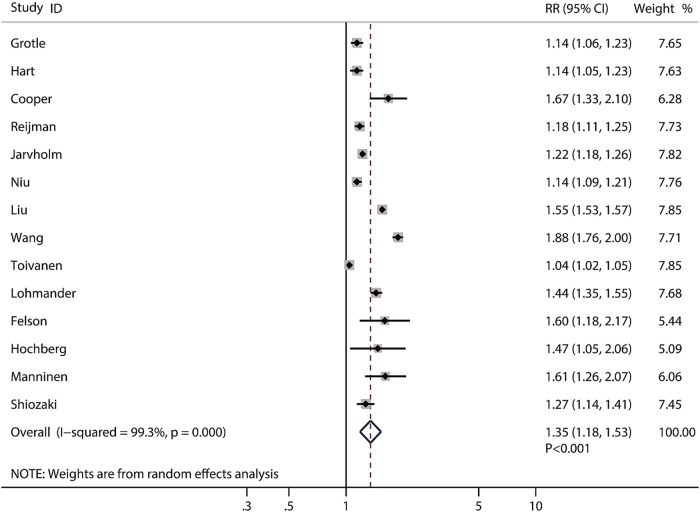

In these 14 prospective studies, 12 were conducted in western countries and 2 were conducted in the Asia-Pacific region. The proportion of males ranged from 0% to 100%; however, the proportion of gender was not a significant predictor of the effect size in this study. Overweight and obesity were significantly associated with higher knee OA risks of 2.45 (95% CI 1.88 to 3.20, p<0.001, figure 2) and 4.55 (95% CI 2.90 to 7.13, p<0.001, figure 3), respectively. The risk of knee OA increases by 35% (RR: 1.35; 95% CI 1.18 to 1.53, p<0.001) with a 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI, which is shown in figure 4. Subgroup analysis showed that the conclusions were consistent with overall analysis based on predefined factors (table 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot for the aggregate risk of knee osteoarthritis for overweight versus normal weight.

Figure 3.

Forest plot for the aggregate risk of knee osteoarthritis for obesity versus normal weight.

Figure 4.

Forest plot for the aggregate risk of knee osteoarthritis with the increase of a 5 kg/m2 of body mass index.

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses

| Group | Number of study | RR and 95% CI | p Value | Heterogeneity (%) | p Value for heterogeneity | p Value for interaction test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | ||||||

| Europe | 9 | 1.30 (1.11 to 1.53) | 0.001 | 99.5 | <0.001 | 0.524 |

| USA or other countries | 5 | 1.44 (1.10 to 1.89) | 0.007 | 97.2 | <0.001 | |

| Number of patients | ||||||

| >1000 | 9 | 1.35 (1.20 to 1.52) | <0.001 | 98.2 | <0.001 | 0.582 |

| <1000 | 5 | 1.28 (1.10 to 1.48) | 0.001 | 87.8 | <0.001 | |

| Per cent male (%) | ||||||

| >60 | 2 | 1.24 (1.12 to 1.37) | <0.001 | 14.1 | 0.281 | 0.383 |

| <60 | 10 | 1.35 (1.15 to 1.59) | <0.001 | 99.5 | <0.001 | |

| Follow-up duration | ||||||

| 10 years or greater | 6 | 1.25 (1.11 to 1.40) | <0.001 | 97.0 | <0.001 | 0.203 |

| <10 years | 8 | 1.41 (1.22 to 1.63) | <0.001 | 97.6 | <0.001 | |

| Adjusted knee injury | ||||||

| Yes | 4 | 1.19 (1.10 to 1.29) | <0.001 | 60.8 | 0.054 | 0.086 |

| No | 10 | 1.39 (1.18 to 1.62) | <0.001 | 99.5 | <0.001 | |

| Study quality | ||||||

| 8 or 9 | 6 | 1.36 (1.11 to 1.66) | 0.003 | 99.7 | <0.001 | 0.535 |

| <8 | 8 | 1.27 (1.17 to 1.37) | <0.001 | 72.5 | 0.001 | |

Significant heterogeneity was found in the models of overweight versus normal weight (I2=86.1%, p<0.001), obesity versus normal weight (I2=94.8%, p<0.001) and the increase of knee OA with a 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI (I2=99.3%, p<0.001). Sensitivity analyses were performed for each of the outcomes. No study crossed zero, and removing any study would have no effect on the pooled WMD (data not shown).

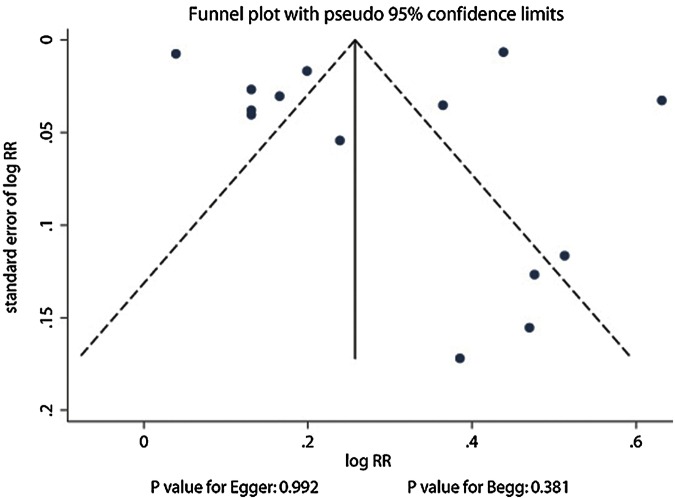

Publication bias was examined by using funnel plots and Egger’s regression test, and results indicated that there was no significant publication bias (p>0.05) in the outcomes of this meta-analysis. Consequently, unpublished data were not evaluated further figure 5.

Figure 5.

Funnel plot for the assessment of publication bias.

Discussion

The aim of this meta-analysis was to review relevant prospective literatures in order to identify the risk of being overweight or obese for knee OA. On the basis of the search strategy and inclusion criteria, a total of 14 original studies were selected and assessed. Pooled RR showed that being overweight or obese was approximately 2.5 and 4.6 times more likely to have knee OA than having normal weight. The risk of knee OA increases by 35% with a 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI. Furthermore, obesity was an independent predictor of knee OA risk regardless of the study country, sample size, gender proportion of participants, duration of follow-up, presence of adjusted knee injury and assessed study quality above or below an NOS score of 8. Subgroup analysis showed that the study country and gender proportion were not significant predictors of the effect sizes in this study.

The findings in this meta-analysis of obesity as a robust risk factor for knee OA were consistent with previous studies.20 30 Manninen et al31 found that increasing from normal weight to overweight during adult life might slightly increase the risk of developing knee OA leading to arthroplasty compared with being constantly overweight during adult life. In a 12-year cohort study, weight loss decreased the high risk of OA due to high BMI among women.32 Fowler-Brown (2014) measured BMI in 653 community dwelling adults aged above 70 years, and found that a 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI was associated with a 32% increase in the probability of knee OA, and at the same time, a 200 pM increase in serum leptin was associated with an increase of 11% in the probability of knee OA. These findings suggested the shared pathogenetic role for metabolic factors with knee OA. The possible mechanism might involve adipokines such as leptin which contributed approximately half of the total effect of obesity on knee OA.7

According to the findings from our systematic meta-analysis, it is valuable for physicians and policymakers to take obesity as one of the most important risks of knee OA into consideration. The Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) guidelines strongly recommended that overweight patients with OA with lower limb OA lost weight and maintained a lower weight level.33 We applied random-effect models based on the heterogeneity of the true effects distribution, which avoided the bias of overstating the precision of findings in fixed-effects models. A limitation of the current study was the small number of studies involved, with limited numbers of participants. This reflected the paucity of high-quality clinical trials that addressed this research topic. Generalising the conclusions from this study to all patients with OA should be performed with caution, and there is still a considerable need for more high-quality studies assessing adiposity using parameters beyond BMI only.

In summary, this meta-analysis confirmed that obesity was a robust risk factor for knee OA. Professionals who treat knee OA should accept a possible weight reduction in mind whenever a patient is significantly overweight.

Footnotes

Contributors: HZ and CC have made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis of data. All authors were involved in the writing of the paper and had final approval of the submitted and published versions.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi: 10.5061/dryad.j4d8r

References

- 1.Riis A, Rathleff MS, Jensen MB et al. Low grading of the severity of knee osteoarthritis pre-operatively is associated with a lower functional level after total knee replacement: a prospective cohort study with 12 months’ follow-up. Bone Joint J 2014;96-B:1498–502. 10.1302/0301-620X.96B11.33726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen R, Henriksen M, Leeds AR et al. Effect of weight maintenance on symptoms of knee osteoarthritis in obese patients: a twelve-month randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:640–50. 10.1002/acr.22504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolf AD, Pfleger B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ 2003;81:646–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:778–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jinks C, Jordan K, Ong BN et al. A brief screening tool for knee pain in primary care (KNEST). 2. Results from a survey in the general population aged 50 and over. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:55–61. 10.1093/rheumatology/keg438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoon KH, Lee JH, Kim JW et al. Epidemic obesity and type 2 diabetes in Asia. Lancet 2006;368:1681–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69703-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowler-Brown A, Kim DH, Shi L et al. The mediating effect of leptin on the relationship between body weight and knee osteoarthritis in older adults. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:169–75. 10.1002/art.38913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lohmander LS, Gerhardsson de Verdier M, Rollof J et al. Incidence of severe knee and hip osteoarthritis in relation to different measures of body mass: a population-based prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:490–6. 10.1136/ard.2008.089748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T et al. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet 2011;378:815–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60814-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Naimark A et al. Obesity and knee osteoarthritis. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med 1988;109:18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blagojevic M, Jinks C, Jeffery A et al. Risk factors for onset of osteoarthritis of the knee in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:24–33. 10.1016/j.joca.2009.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S et al. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet 1999;354:1896–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anuurad E, Shiwaku K, Nogi A et al. The new BMI criteria for Asians by the regional office for the western pacific region of WHO are suitable for screening of overweight to prevent metabolic syndrome in elder Japanese workers. J Occup Health 2003;45:335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. 2009. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed Aug 2014).

- 16.Jennings JH, Digiovine B, Obeid D et al. The association between depressive symptoms and acute exacerbations of COPD. Lung 2009;187:128–35. 10.1007/s00408-009-9135-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grotle M, Hagen KB, Natvig B et al. Obesity and osteoarthritis in knee, hip and/or hand: an epidemiological study in the general population with 10 years follow-up. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2008;9:132 10.1186/1471-2474-9-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hart DJ, Doyle DV, Spector TD. Incidence and risk factors for radiographic knee osteoarthritis in middle-aged women: the Chingford Study. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper C, Snow S, McAlindon TE et al. Risk factors for the incidence and progression of radiographic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:995–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reijman M, Pols HA, Bergink AP et al. Body mass index associated with onset and progression of osteoarthritis of the knee but not of the hip: the Rotterdam Study. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:158–62. 10.1136/ard.2006.053538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Järvholm B, Lewold S, Malchau H et al. Age, bodyweight, smoking habits and the risk of severe osteoarthritis in the hip and knee in men. Eur J Epidemiol 2005;20:537–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niu J, Zhang YQ, Torner J et al. Is obesity a risk factor for progressive radiographic knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:329–35. 10.1002/art.24337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu B, Balkwill A, Banks E et al. Relationship of height, weight and body mass index to the risk of hip and knee replacements in middle-aged women. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:861–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/kel434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Simpson JA, Wluka AE et al. Relationship between body adiposity measures and risk of primary knee and hip replacement for osteoarthritis: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 2009; 11:R31 10.1186/ar2636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toivanen AT, Heliövaara M, Impivaara O et al. Obesity, physically demanding work and traumatic knee injury are major risk factors for knee osteoarthritis—a population-based study with a follow-up of 22 years. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:308–14. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Felson DT, Zhang Y, Hannan MT et al. Risk factors for incident radiographic knee osteoarthritis in the elderly: the Framingham Study. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:728–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hochberg MC, Lethbridge-Cejku M, Tobin JD. Bone mineral density and osteoarthritis: data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2004;12(Suppl A):S45–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manninen P, Riihimaki H, Heliovaara M et al. Overweight, gender and knee osteoarthritis. Int J Obes 1996;20:595–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiozaki H, Koga Y, Omori G et al. Obesity and osteoarthritis of the knee in women: results from the Matsudai Knee Osteoarthritis survey. The Knee 1999;6:189–92. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szoeke CE, Cicuttini FM, Guthrie JR et al. Factors affecting the prevalence of osteoarthritis in healthy middle-aged women: data from the longitudinal Melbourne Women's Midlife Health Project. Bone 2006;39:1149–55. 10.1016/j.bone.2006.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manninen P, Riihimaki H, Heliövaara M et al. Weight changes and the risk of knee osteoarthritis requiring arthroplasty. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:1434–7. 10.1136/ard.2003.011833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Felson DT, Zhang Y, Anthony JM et al. Weight loss reduces the risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in women. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med 1992;116:535–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dougados M. Monitoring osteoarthritis progression and therapy. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2004;12(Suppl A):S55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]