Abstract

Objectives

The objectives of this study are to: (1) examine the pattern of price elasticity of three major tobacco products (bidi, cigarette and leaf tobacco) by economic groups of population based on household monthly per capita consumption expenditure in India and (2) assess the effect of tax increases on tobacco consumption and revenue across expenditure groups.

Setting

Data from the 2011–2012 nationally representative Consumer Expenditure Survey from 101 662 Indian households were used.

Participants

Households which consumed any tobacco or alcohol product were retained in final models.

Primary outcome measures

The study draws theoretical frameworks from a model using the augmented utility function of consumer behaviour, with a two-stage two-equation system of unit values and budget shares. Primary outcome measures were price elasticity of demand for different tobacco products for three hierarchical economic groups of population and change in tax revenue due to changes in tax structure. We finally estimated price elasticity of demand for bidi, cigarette and leaf tobacco and effects of changes in their tax rates on demand for these tobacco products and tax revenue.

Results

Own price elasticities for bidi were highest in the poorest group (−0.4328) and lowest in the richest group (−0.0815). Cigarette own price elasticities were −0.832 in the poorest group and −0.2645 in the richest group. Leaf tobacco elasticities were highest in the poorest (−0.557) and middle (−0.4537) groups.

Conclusions

Poorer group elasticities were the highest, indicating that poorer consumers are more price responsive. Elasticity estimates show positive distributional effects of uniform bidi and cigarette taxation on the poorest consumers, as their consumption is affected the most due to increases in taxation. Leaf tobacco also displayed moderate elasticities in poor and middle tertiles, suggesting that tax increases may result in a trade-off between consumption decline and revenue generation. A broad spectrum rise in tax rates across all products is critical for tobacco control.

Keywords: HEALTH ECONOMICS, PUBLIC HEALTH, STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The most recent and nationally representative data are used to estimate price elasticity using a model to correct for measurement error in reported prices and quantities of consumed tobacco products.

The study provides the first national estimates for leaf tobacco by expenditure tertiles (wealth status).

The price elasticity estimates which are derived from the unit level records of NSS are household and not individual estimates. Individual estimates are not possible due to paucity of data.

It is not possible to estimate whether reductions in consumption across tobacco users are due to quitting, decrease in frequency of use, or decreased/delayed initiation, for which further research is needed.

Introduction

In India, more than one-third of adults (approximately 275 million persons) consume tobacco products.1 Use of these products is not uniform, with cigarette use concentrated in urban areas and smokeless tobacco and bidii (an indigenous hand-rolled smoked product) use prevalent in rural areas. In addition, various forms of smokeless tobacco are consumed by a quarter of the Indian population.1 In 2011–2012, almost 43% of rural and 22% of urban households consumed one or another form of tobacco.2

The Government of India enacted the ‘Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of Advertisement and Regulation of Trade and Commerce, Production, Supply and Distribution) Act, 2003’ in 2004; however, its enforcement and implementation are not uniform.3 Taxation forms the major component of tobacco control policy in the country, with both central and state governments levying different taxes.ii International obligations under the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control stipulate that all tobacco products be taxed at a target tax incidence of 75%.4 However, in India, the differential tax rate is well below this. There have been regular increases in tax, focused on cigarettes, yet cigarettes are becoming more affordable in the country due to rising incomes and economic growth.5 In contrast, bidi and tobacco used for its manufacture, which are the most widely consumed smoking products, are exempt from value-added tax (VAT) in many states. Together with central excise, bidis have a tax rate which is on average only 9% of the retail price.6 Further obscuring bidi taxation objectives are government subsidies: bidi excise rates (per 1000 sticks) depend on whether they are handmade (98%) or machine-made (2%), with handmade bidis produced by manufacturers producing less than 2 million pieces a year exempt from taxation.7 The taxation of smokeless tobacco products is even more complex, with raw materials and unmanufactured tobacco exempt from tax or taxed between 4% and 5%.8 A tiered and complex tobacco taxation structure, particularly for cigarettes, has been associated with high cigarette price variability,9 which is especially important for tax governance. The Indian government has proposed moving to a unified Goods and Services Tax (GST) by bringing together state and central taxes and addressing complexities in the current system; it is important to increase taxes and employ supplementary excise on demerit goods such as tobacco.10 It is equally important to bring informal manufacturing of bidi and smokeless tobacco under the tax net and remove detrimental government subsidies on bidi manufacturing, in order to deter consumption, increase the tax base and maximise revenue generation.7

Price elasticity is the key parameter to ascertain the change in demand of a good with respect to changes in price. Studies have shown that price increases, by means of increased taxation, reduce overall tobacco use by deterring initiation and continued use in young people, and promoting reductions in the quantity of tobacco consumed and increased cessation in long-term users.11 12 The effect of higher cigarette prices has been suggested to be more marked in promoting cessation in low-income and middle-income countries13 and exposure to more tobacco control measures is associated with quitting.12 Most studies use consumer behaviour theory to derive a utility function to show the relationship between price and demand. In high-income countries, estimates of price elasticity of cigarette demand range from −0.25 to −0.50, while estimates from low-income and middle-income countries range from −0.50 to −1.00.14–18 While numerous studies analyse the aggregate price elasticity of demand, very few have examined elasticities by income or wealth status of population groups. This is significant because consumer preferences vary across socioeconomic strata (SES). A study from Sri Lanka found the total price elasticity of demand to be −0.29 in the richest expenditure quintile, varying from −0.55 to −0.64 among the other four expenditure quintiles.19

There are a few studies on the price elasticities of tobacco products in India, and they present varying results. One of the earliest studies estimated price elasticities by rural/urban living status, for bidis, cigarettes and leaf tobacco, using Consumer Expenditure Survey (CES) data from the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) for the year 1999–2000.20 Bidis had the highest price elasticity of −0.922 in rural areas and −0.855 in urban areas, followed by leaf tobacco with elasticities of −0.874 in urban areas and −0.871 in rural areas. Cigarettes were the least price elastic, with elasticities of −0.38 in rural areas and −0.196 in urban areas. Another study assessed own and cross price elasticities of cigarettes, bidis and country liquor, using similar sets of consumer expenditure data from 1993–1994 to 2007.21 Using CES data from 2004 to 1905, estimated price elasticities were: −0.61 for bidis in urban and rural areas; and for cigarettes, 0.15 in rural areas and −0.30 in urban areas. The same study also estimated price elasticities for cigarettes and bidis by economic quintile classes, with bidi elasticities of −0.953 for quintiles 1–3 (lower quintiles) and −0.889 for quintiles 4–5 (higher quintiles). The corresponding values for cigarettes were −0.960 and −1.021. Another study used data from 2000 and 2004 to estimate the price elasticity of cigarette, bidi and gutkha demand in Indian youth. Higher cigarette and bidi prices were found to significantly reduce the prevalence of cigarette and bidi smoking (elasticities of −0.17 and −1.17, respectively), and higher prices also significantly reduced cigarette consumption among young smokers (conditional demand elasticity being −0.3).22 A study using survey data from 2010 to 2011 found that the prices of both bidis and cigarettes did not influence consumption behaviour in Indian adults.23

In this backdrop of a number of studies employing diverse methods, there exists scope for further study to see the price responsiveness of tobacco products in India, in order to suggest more appropriate tobacco pricing strategies for policymakers. Also, given the availability of multiple tobacco products in different price brackets and their equally complex and inconsistent taxation, Indian consumers are presented with numerous alternatives if their product of choice becomes too expensive.The objectives of this paper are thus twofold: (1) to estimate price elasticity of tobacco products by SES strata from the latest available consumer expenditure data and (2) to simulate the effect of tax increases on tobacco consumption and revenue across these SES groups.

Materials and methods

Data sources

The study uses nationally representative CES data collected at the household level by the NSSO during the year 2011–2012.24 The survey covers consumption expenditure information on a range of commodities including tobacco products, using a 30-day reference period for consumables such as food, fuel, tobacco and intoxicants. Household characteristics such as social group, religion, age and educational qualifications of household members are also collected. The data are collected in adherence to ethical standards and all individual identifiers removed. In this study, three major tobacco products bidi, cigarette and leaf tobacco are considered. The values under the entries of leaf tobacco, zarda, kimam and surti in the source survey have been combined to form the category leaf tobacco.

Study sample

The survey covers all Indian states through a stratified multistage sampling design. Both rural and urban samples have been drawn in the form of two independent subsamples, totalling 101 662 households. More details on the sampling and survey methodology can be found in the survey report.24 Appropriate survey weights have been used and results can be generalised to the entire Indian population.

We determined economic living status of households by dividing them into expenditure tertiles on the basis of monthly per capita (per person) total consumption expenditure (MPCE) of households. We first graphed box plots and histograms of unit values and budget shares, and subsequently dropped budget share values which were beyond 5 SDs from the mean, as was done in the earlier literature.21 25 26 The final sample of households was: 16 525 in tertile 1 (T1), 18 018 in T2 and 15 165 in T3.

Research design

The following derivation has been drawn from earlier work on this topic.20 27–29 In India, there is a lack of data on prices and quantities consumed of different tobacco products. Therefore, an indirect method using unit values (total expenditure divided by total quantity consumed) of each tobacco product is used. The NSSO surveys provide information on expenditures and quantity of tobacco products consumed by households, from which unit values are estimated.

A theoretical model appropriate for survey data is followed to estimate price elasticity of tobacco products.27–29 The model is based on the theory of consumer behaviour where households are assumed to choose both quantity and quality so that expenditure on a good reflects quantity, quality and price. It indicates that in addition to quantity, quality is augmented in the utility function of the household. Preferences for tobacco products are assumed to be uniform at the village level, as they reflect the preferences of each household in a village in aggregate, mainly because all households at the village level can be assumed to face the same price. Households are therefore geographically clustered at the village level within the sample.

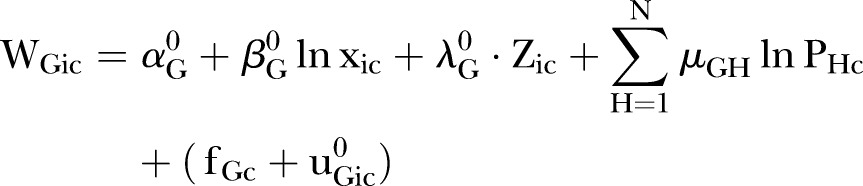

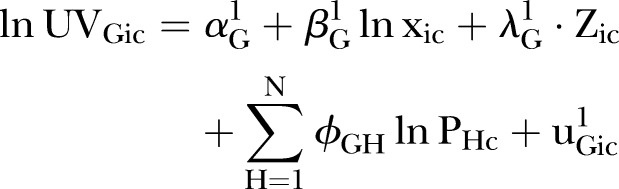

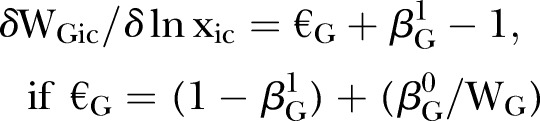

The budget shares relating to village demand patterns are regressed on average village prices. The unit values of each tobacco product (bidi, cigarette and leaf tobacco) are used as a proxy for their prices. Equations (1) and (2) represent the budget shares and unit values to household expenditures, household characteristics and prices of commodities, which are used in the absence of tobacco prices to estimate expenditure elasticities:

|

1 |

|

2 |

where WGic is the budget share and UVGic the unit value of good G in the budget of household i living in cluster (village) c. Here, household tobacco budget shares are a function of the logarithm of total household expenditure, household characteristics and prices of tobacco products. In the equations, x is the household expenditure, Z the vector of household characteristics and N the price of N number of tobacco products. PH represents the price of the commodity for all households. The model assumes a common price for all households in a cluster/village, which is distinguished by ‘H’.

Household characteristics include covariates such as: log of household expenditure, log of household size, ratio of males in the household, ratio of adults (≥15 years) in the household, mean years of education of household members, maximum years of education of any household member, religion, social groupiii (scheduled caste, scheduled tribe, other backward caste and other castes) and household type (urban or rural). The coefficients estimated from these two equations do not provide the elasticity as such; this is discussed elsewhere.27–29 The first element of the residual in equation (1), fGc, is a village level effect that is the same for all households within a village and can be considered either as a random or fixed effect (since households are distinguished according to clusters, the model is similar to a panel data regression).20 It is also assumed that the unobserved fGc and prices are uncorrelated with each other.  is the SE that captures measurement error involved in the budget share and the variations in quality among products. Equation (2) represents the unit value. The natural logarithm of the unit value is a function of household expenditure (x) and household characteristics (Z) and price as before.

is the SE that captures measurement error involved in the budget share and the variations in quality among products. Equation (2) represents the unit value. The natural logarithm of the unit value is a function of household expenditure (x) and household characteristics (Z) and price as before.  is the expenditure elasticity of quality. Differentiating equation (1) with respect to lnx, we get,

is the expenditure elasticity of quality. Differentiating equation (1) with respect to lnx, we get,

|

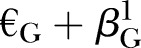

Here, WGic is the budget share and €G the elasticity of expenditure with respect to quantity. Therefore, the total expenditure elasticity of quantity and quality together will be  . Similarly, if

. Similarly, if  is price elasticity,

is price elasticity,  ; WG is the mean budget share for all households.

; WG is the mean budget share for all households.

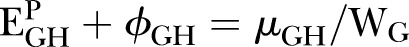

Estimation of the above stripped-down model involves two stages. First, since it is assumed that market prices do not vary within a village at a certain point of time (cross section data), the non-price parameters, that is, α, β and λ can be estimated using within-village information by simple ordinary least squares regression. The second stage involves algebraic treatments linking the theory on quality and quantity elasticities for the effect of price on budget share. Using the first-stage estimators of demand regressions, the intercluster information is used to estimate price elasticities from the transformed regressions:

|

3 |

|

4 |

where the new variable  are budget share and unit value, respectively, after netted out total expenditure and household characteristics. Since the parameters associated with unobservable prices are the ultimate target, the same can be algebraically estimated by first stage residuals (

are budget share and unit value, respectively, after netted out total expenditure and household characteristics. Since the parameters associated with unobservable prices are the ultimate target, the same can be algebraically estimated by first stage residuals ( ) and

) and  at each cluster such that the final matrix of price elasticities [E] is observed from matrix B, where

at each cluster such that the final matrix of price elasticities [E] is observed from matrix B, where  and is estimated by combining cluster size with

and is estimated by combining cluster size with  ,

,  and

and  ; all are estimable.23

24

; all are estimable.23

24

The analysis is done separately for MPCE tertile groups. The final sample consists of households which reported consumption of any tobacco or alcohol product in the source survey instead of only households with positive tobacco consumption, hence reducing the magnitude of any selection bias to some extent.27–29 This also makes our study sample comparable to that in a previous Indian study using similar specifications.20 Monthly per capita consumption of cigarettes and bidis was recorded in number of sticks, and that of leaf tobacco in grams.

Results and discussion

Table 1 shows the unit values and budget shares of bidi, cigarette and leaf tobacco for the total sample and by the tertile groups. All three products exhibit consistently higher unit values across tertiles, indicating that better-off consumers choose more expensive products. Overall, tobacco budget shares were approximately 2% for all expenditure tertiles. Budget shares of bidis were 0.81% overall, decreasing from 0.99% in T2 to 0.62% in T3. This may be due to both rising incomes as well as a preference for cigarettes in richer groups. For cigarettes, the overall budget share was 0.5%, increasing from 0.08% in T1, to 0.27% in T2, to 0.69% in T3. For leaf tobacco, budget shares were highest in T1 (0.35%).

Table 1.

Tertile-wise unit values and budget shares of bidi, cigarette and leaf tobacco, India, 2011–2012

| All India |

T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV | BS | UV | BS | UV | BS | UV | BS | |

| Bidi | ||||||||

| Observations | 19 395 | 49 708 | 7124 | 16 525 | 7732 | 18 018 | 4539 | 15 165 |

| Mean | 0.3672 | 0.81 | 0.3255 | 0.93 | 0.376 | 0.99 | 0.4081 | 0.62 |

| CI | (0.36 to 0.37) | (0.79 to 0.82) | (0.32 to 0.33) | (0.90 to 0.95) | (0.37 to 0.38) | (0.97 to 1.02) | (0.40 to 0.41) | (0.59 to 0.64) |

| Cigarettes | ||||||||

| Observations | 9748 | 49 708 | 959 | 16 525 | 3169 | 18 018 | 5620 | 15 165 |

| Mean | 3.1209 | 0.50 | 2.8323 | 0.08 | 3.1292 | 0.27 | 3.4494 | 0.69 |

| CI | (3.09 to 3.14) | (0.49 to 0.52) | (2.76 to 2.90) | (0.07 to 0.08) | (3.09 to 3.17) | (0.26 to 0.29) | (3.42 to 3.48) | (0.66 to 0.71) |

| Leaf tobacco | ||||||||

| Observations | 16 810 | 49 708 | 6895 | 16 525 | 6028 | 18 018 | 3887 | 15 165 |

| Mean | 0.3305 | 0.25 | 0.256 | 0.35 | 0.3313 | 0.25 | 0.4039 | 0.15 |

| CI | (0.32 to 0.34) | (0.24 to 0.25) | (0.25 to 0.26) | (0.34 to 0.36) | (0.32 to 0.34) | (0.25 to 0.26) | (0.39 to 0.42) | (0.14 to 0.15) |

| Tobacco (total) | ||||||||

| Observations | 49 708 | 16 525 | 18 018 | 15 165 | ||||

| Mean | NA | 2.08 | NA | 1.91 | NA | 2.06 | NA | 1.96 |

| CI | NA | (2.06 to 2.11) | NA | (1.88 to 1.94) | NA | (2.03 to 2.09) | NA | (1.92 to 1.99) |

BS, budget share (mean in %); NA, not applicable; T1, tertile 1 (poorest); T2, tertile 2 (middle); T3, tertile 3 (richest); UV, unit value in rupees per stick for cigarettes and bidis and rupees per gram for leaf tobacco.

Table 2 shows the monthly mean per person consumption (quantities) of the three tobacco products among tobacco consuming households. On average, T3 consumers use the largest quantities of all three products. It indicates that in addition to choosing higher priced products within the same product category (as per online supplementary table S1), Indian consumers also consistently consume a greater number of products as their expendable income increases, maximising both quality and quantity preferences.

Table 2.

Tertile-wise monthly per person consumption of bidi, cigarette and leaf tobacco in tobacco consuming households, India, 2011–2012

| T1 | T2 | T3 | All India | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bidi (number of sticks) | 23.49 | 35.70 | 36.91 | 30.09 |

| Cigarettes (number of sticks) | 0.26 | 1.25 | 6.34 | 1.69 |

| Leaf tobacco (in grams) | 13.29 | 13.87 | 14.06 | 13.62 |

T1, tertile 1 (poorest); T2, tertile 2 (middle); T3, tertile 3 (richest).

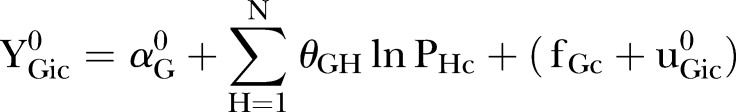

We present coefficients for household expenditure and household size from tertile-wise unit value and budget share regressions, and expenditure elasticities in online supplementary table S1. The coefficient of the logarithm of expenditure in the unit value equation yields the expenditure elasticity of quality. Cigarettes have the highest expenditure elasticity of quality in T3, implying that a doubling of household expenditure will increase the average price paid for cigarettes by 7%. Logarithms of household size coefficients are approximately similar in size and opposite in sign to the coefficients of the logarithm of household expenditure in the unit value equations. This implies that increases in household size are likely to reduce household income. Coefficients of the logarithms of household expenditure and household size are generally opposite in sign in the budget share regressions for both bidis and cigarettes. At a constant household expenditure, an increase in household size leads to increased budget shares on bidis, but reductions in budget shares on cigarettes and leaf tobacco.

Table 3 shows price elasticities of cigarettes, bidis and leaf tobacco across tertiles; bootstrapped SEs for own-price elasticities were estimated from 1000 replications from cluster-level data.27 Price elasticities for bidis were highest in T1 (−0.4328) and lowest in T3 (−0.0815). This is intuitive as poorer consumers are expected to be more responsive to price changes. T3 consumers are almost inelastic to bidi price changes. For cigarettes, own price elasticities were highest in T1 (−0.832) and lowest in T2 (−0.0913), with elasticity of −0.2645 in T3. Leaf tobacco elasticities were highest in T1 (−0.557) and T2 (−0.4537), again showing a similar pattern in responsiveness as cigarettes and bidis. All elasticity estimates are more than twice bootstrapped SEs, signifying that they are statistically significant.

Table 3.

Own price elasticity estimates of tobacco products, 2011–2012

| Tertile 1, poorest |

Tertile 2, middle |

Tertile 3, richest |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | C | L | B | C | L | B | C | L |

| −0.4328 (0.0023) | −0.832 (0.0062) | −0.557 (0.0014) | −0.2499 (0.0020) | −0.0913 (0027) | −0.4537 (0017) | −0.0815 (0.0028) | −0.2645 (0.0015) | −0.0507 (0.0026) |

SEs in brackets; estimates in bold are greater than twice their bootstrapped SE.

B, bidis; C, cigarettes; L, leaf tobacco.

Cross price elasticity estimates are shown in online supplementary table S2. They show that bidis are complementary to cigarettes in T2 and T3. This implies that if the price of bidis increases, the demand for cigarettes declines. Positive cross price elasticities between bidis and leaf tobacco indicate that these products are substitutes, with increases in the price in bidis causing demand shifts to leaf tobacco, in T2 and T3.

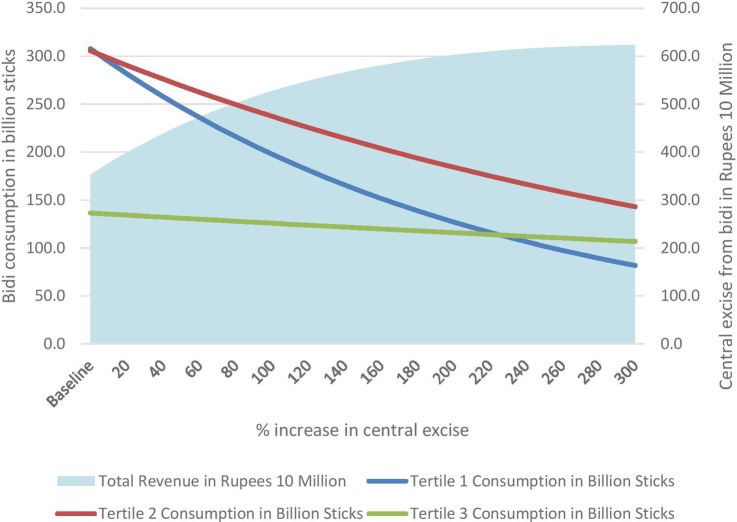

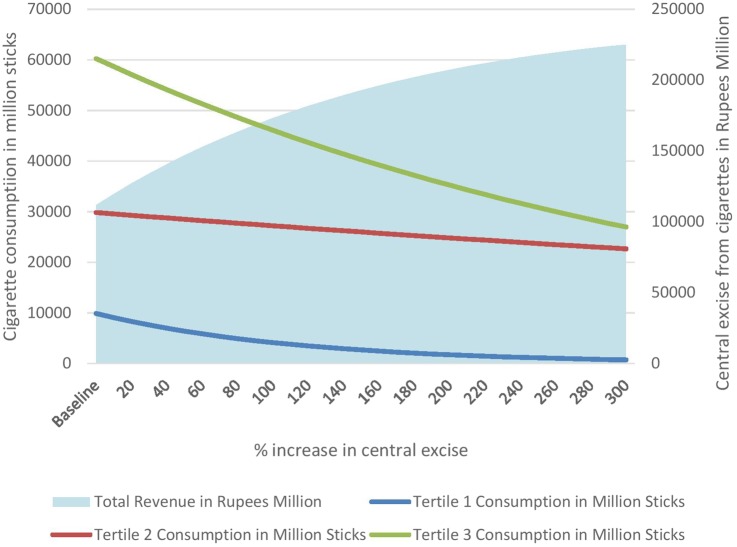

Simulation exercise

We next simulated the effects on consumption of cigarettes and bidis if the current excise tax was to be increased, using simulation models which have been used in a previous Indian study.20 The details of the simulation exercise are found in the online supplementary file and supplementary table S3. We plot the expected changes in consumption of the units of bidis and cigarettes consumed nationally by tertiles, based on 10% incremental central excise increases in figures 1 and 2, respectively, using estimated price elasticities. We assume that there would be constant reductions in consumption (elasticity) across consecutive tax increases; changes in price correspond to changes in tax; and there would be no substitution effects due to the changes in price.20 The decreased consumption is in units of sticks consumed and we make no inferences on whether the reductions in consumption are due to cessation, delayed initiation or decreased frequency of use. While it is implausible to estimate the total effects of increased tax, the models help to illustrate the relative reductions in units of tobacco consumed across tertiles alongside revenue generation for the government. In figure 1, the most marked reductions in bidi consumption are observed in T1 and T2, with T3 consumers almost inelastic to bidi price changes, even after 300% increases in bidi central excise, as compared to baseline levels. Bidi revenue continues to increase with tax hikes, and begins to plateau around 300%. Figure 2 shows changes in cigarette consumption with an increase in central excise. The most marked reductions in cigarette consumption are observed in T1 with a 300% increase in tax; however, the moderate responsiveness of T3 cigarette users coupled with the much higher proportion of T3 in comparison to T1 consumers means that the absolute reductions in cigarette consumption are highest in T3. Cigarette revenues continue to rise with increases in excise.

Figure 1.

Changes in bidi consumption and revenue with per cent increase in central excise for expenditure tertiles, 2011–2012.

Figure 2.

Changes in cigarette consumption and revenue with per cent increase in central excise for expenditure tertiles, 2011–2012.

Conclusion

This study provides estimates of price elasticities of the three major tobacco products consumed by economic status of households in India. Results demonstrate that poorer consumers are more sensitive to tobacco price changes, and opportunity to increase tobacco prices through taxation, leading to substantial reductions in bidi and leaf tobacco consumption among the poorer and middle wealth (expenditure) tertiles. This has wider ramifications on age of initiation of tobacco use (as increase in taxes are found to deter the age of initiation of tobacco products), duration and intensity of use, and promotion of quitting behaviour. Decreased consumption of tobacco, whether by quitting, reduced frequency of use or delayed initiation, may have implications on households’ resource allocation on other goods, such as food, education and health, and overall quality of life.30 31 Our results yield price elasticities that are lower than those reported earlier in India, especially for bidis. Guindon et al21 estimated elasticities for bidis, cigarettes and country liquor using CES data, for both cross-sectional and pooled analyses from 1993–1994, 1999–2000 and 2004–2005. With a similar application of Deaton's methodology and using villages as clusters, they reported price elasticities of −0.61 for bidis and −0.06 for cigarettes, nationally, in 2004–2005. In pooled analyses of CES data from 1999–2000 to 2007–2008, elasticities by expenditure quintiles were estimated: bidis, −0.954 for low quintiles and −0.889 for high quintiles; cigarettes, −0.960 for low quintiles and −1.021 for high quintiles. Elasticities from our estimations are lower for all tertiles in comparison to these estimates; yet both results demonstrate the higher price responsiveness of poorer bidi consumers. Results may not be strictly comparable due to the inclusion of country liquor consuming households and exclusion of leaf tobacco, and alternate specifications in the analyses in Guindon et al; as well as the inclusion of annual (smaller sample rounds) CES data in their pooled analyses which have a higher proportion of urban households than the quinquennial (five yearly) CES data used in the present analyses. John's20 study also reported higher elasticities than our estimates for both bidis and leaf tobacco in urban and rural areas; the use of the same methodological approach, inclusion of both tobacco and alcohol using households, and leaf tobacco in the sample and use of quinquennial CES data from 1999 to 2000, suggests greater comparability of our results with John's study. This may be indicative of Indian consumers becoming more inelastic to tobacco price increases, in line with consumers in higher income countries. Taxation has thus not kept pace with rising incomes and economic growth, raising questions on increasing affordability of all tobacco products and indexing of taxation to inflation.

Currently, the motivating rationale for tax measures for tobacco in the country is fiscal (to maximise excise revenue generation), rather than for the public health goal of reducing consumption. This is reflected in the differential taxation on tobacco products, with cigarettes taxed heavily compared to the more prevalent bidis and smokeless forms. In 2011–2012, VAT on cigarettes, consumed by 5.7% of the population, ranged from 12.5% in Kerala, Uttarakhand and Chandigarh, to 40% in Rajasthan, with most states levying taxes ≤20%.1 Bidi VAT was nil in 2011–2012 in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Haryana, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Odisha, Uttarakhand and West Bengal. This is alarming considering that Uttarakhand, Haryana and West Bengal are states with bidi consumption well above the national average.1 Taxation on smokeless products was even more heterogeneous, with central excise levies based on the manufacturing capacity of packaging machines, which is arbitrarily set on the presumed number of hours the machine is operational, and can be easily circumvented.32 Further, the multiplicity of taxes on the plethora of smokeless products makes tax administration and governance difficult.9 For all tobacco products, wide variation of VAT rates across states promotes illicit trade and interstate smuggling, making harmonisation of taxes critical.

Overall, estimated elasticities for lower tertiles were higher, indicating that poorer consumers are more price responsive. Our study provides evidence of the positive distributional effects of uniform bidi taxation on the poor, as poorer consumers are those whose consumption is affected the most due to increases in bidi taxation. Cigarette smokers are the most resistant to price changes. Our results provide empirical evidence that tobacco taxes for all products can be raised to well above current levels without negatively affecting tax revenue and maximising public health gains. While a broad spectrum rise in tax rates across all tobacco products is critical, simplifying the tax structure and tax governance must receive utmost importance in the current policy regime against tobacco control, especially as India is set to embark on the new GST in the near future.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the National Sample Survey Organisation, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, for making available the consumer expenditure data used for this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: SS, SS2 and AK conceptualised and planned the study. SS2 led the data analysis, interpretation and writing of the manuscript. AK and SS contributed to the interpretation and writing of the manuscript and provided the overall supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded through a grant (project number 106412-004) from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Canada (URL: http://www.idrc.ca/EN/Pages/default.aspx).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Bidis are an indigenous smoking product consisting of tobacco rolled in the dried leaf of tendu trees. They have historically been consumed by poorer sections of society. Bidi manufacturing is subsidised by the Government of India through tax exemptions as it is primarily an informal industry.

India follows a dual taxation structure for tobacco products. The central excise imposes specific excise duty on a tiered basis for cigarettes on the basis of weight, length, volume, thickness of a product and presence of a filter. Similarly bidis have specific excise based on whether man or machine made. All other tobacco products, for example, smokeless products are taxed on an ad valorem basis (on the basis of percentage of the retail price of the product). There are also some additional excise duties and health cess. States also impose varying rates of VAT and entry tax. For more details see John et al.6

Social groups as per the NSS survey are classifications formed by combining traditional social hierarchical identities to which the households identify with, into the following groups: scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, other backward caste and other castes. The Government of India uses this system to identify traditionally disadvantaged groups for positive discrimination in various social and development initiatives.

References

- 1.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS). Mumbai and ministry of health and family welfare, Government of India, 2010. (2010) Global Adult Tobacco Survey India (GATS India), 2009–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Key Indicators of Household Consumer Expenditure in India, 2011-12. [data file] Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India. http://mospi.nic.in/Mospi_New/Admin/publication.aspx.

- 3. The Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of Advertisement and Regulation of Trade and Commerce, Production, Supply and Distribution) Act. 2003. [statute on the Internet]. c2015 [cited 2015 March]. http://rctfi.org/notification/1.pdf.

- 4. World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241591013.pdf.

- 5.van Walbeek C. A simulation model to predict the fiscal and public health impact of a change in cigarette excise taxes. Tob Control 2010;19:31–6. 10.1136/tc.2008.028779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.John RM, Rao RK, Rao MG et al. . The economics of tobacco and tobacco taxation in India. Paris: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sunley EM. India: the tax treatment of bidis. Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use, 2008. ISBN: 978-2-914365-35-2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Government of India. Central Board of Excise and Customs, Department of Revenue, Ministry of Finance. Section V Chapter 24 Tobacco and Manufactured Tobacco Substitutes 2014. http://www.cbec.gov.in/cae1-english.htm

- 9.Shang C, Chaloupka FJ, Fong GT et al. . The association between tax structure and cigarette price variability: findings from the ITC Project. Tob Control 2015;24(Suppl 3):iii88–93. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad E, Poddar S. GST Reforms And Intergovernmental Considerations in India. LSE Asia Research Centre Working Paper 26 2009. http://www.lse.ac.uk/asiaResearchCentre/_files/ARCWP26-AhmadPoddar.pdf

- 11.Chaloupka FJ. Macro-social influences: the effects of prices and tobacco-control policies on the demand for tobacco products. Nicotine Tob Res 1999;1(Suppl 1):S105–9. http://ntr.oxfordjournals.org/content/1/Suppl_2/S77.abstracthttp://ntr.oxfordjournals.org/content/1/Suppl_2/S77.abstract 10.1080/14622299050011861http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14622299050011861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kostova D, Chaloupka FJ, Shang C. A duration analysis of the role of cigarette prices on smoking initiation and cessation in developing countries. Eur J Health Econ 2015;16:279–88. 10.1007/s10198-014-0573-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shang C, Chaloupka F, Kostova D. Who quits? An overview of quitters in low- and middle-income countries. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16(Suppl 1):S44–55. 10.1093/ntr/ntt179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaloupka FJ, Straif K, Leon ME. Effectiveness of tax and price policies in tobacco control. Tob Control 2011;20:235–8. 10.1136/tc.2010.039982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaloupka FJ, Hu T, Warner KE et al. . The taxation of tobacco products. In: Jha P, Chaloupka FJ, eds. Tobacco control in developing countries. Oxford, UK and New York, NY, USA, Oxford University Press, 2000;237–72. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hidayat B, Thabrany H. Cigarette smoking in Indonesia: examination of a myopic model of addictive behaviour.s Int J Environ Res Public Health 2010;7:2473–85. 10.3390/ijerph7062473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karki YB, Pant KD, Pande BR. A Study on the Economics of Tobacco in Nepal. HNP Discussion Paper Series. Economics of Tobacco Control Paper No. 13 Washington: The World Bank, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mushtaq N, Mushtaq S, Beebe LA. Economics of tobacco control in Pakistan: estimating elasticities of cigarette demand. Tob Control Tob Control 2011;20:431–5. 10.1136/tc.2010.040048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arunatilake N. An Economic Analysis of Tobacco Demand in Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka Econ J 2002;3:96–120. [Google Scholar]

- 20.John RM. Price elasticity estimates for tobacco products in India. Health Policy Plan 2008;23:200–9. 10.1093/heapol/czn007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guindon GE, Nandi A, Chaloupka FJ et al. . Socioeconomic differences in the impact of smoking tobacco and alcohol prices on smoking in India. NBER Working Paper No. 17580 November 2011.

- 22.Joseph RA, Chaloupka FJ. The influence of prices on youth tobacco use in India. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16(Suppl 1): S24–9. 10.1093/ntr/ntt041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pawar PS, Pednekar MS, Gupta PC et al. . The relation between price and daily consumption of cigarettes and bidis: findings from the Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Wave 1 Survey. Indian J Cancer. 2014;51(Suppl 1):S83–7. 10.4103/0019-509X.147479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India. National Sample Survey Organization. Key Indicators of Household Consumer Expenditure in India, 2011-12. 2012 (available from http://mospi.nic.in/Mospi_New/Admin/publication.aspx).

- 25.Cox TL, Wohlgenant MK. Prices and quality effects in cross-sectional demand analysis. Am J Agric Econ 1986;68:908–19. 10.2307/1242137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deaton A, Tarozzi A. Prices and poverty in India. Princeton: Princeton University, Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deaton A. The analysis of household surveys: a microeconometric approach to development policy. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deaton A. Household survey data and pricing policies in developing countries. World Bank Econ Rev 1989;3:183–210. 10.1093/wber/3.2.183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deaton A. Price elasticities from survey data: extensions and Indonesian results. J Econ 1990;44:281–309. 10.1016/0304-4076(90)90060-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Efroymson D, Ahmed S, Townsend J et al. . Hungry for Tobacco: an analysis of the economic impact of tobacco on the poor in Bangladesh. Tob Control 2001;10:212–17. 10.1136/tc.10.3.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.John RM. Crowding out effect of tobacco expenditure and its implications on household resource allocation in India. Soc Sci Med 2008;66:1356–67. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Government of India Chewing Tobacco and Unmanufactured Tobacco Packing machines (Capacity Determination and Collection of Duty) Rules, 2010. [statute on the Internet]. c2015 [cited 2015 March]. http://www.cbec.gov.in/htdocs-cbec/excise/cxrules/cx-chewing-tobacco-rules.