Abstract

Objectives

The US thyroid cancer incidence rates are rising while mortality remains stable. Trends are driven by papillary thyroid cancer (PTC), the predominant cancer subtype which has a very good prognosis. We hypothesised that health insurance and high census tract socioeconomic status (SES) are associated with PTC risk.

Design

Relationships between thyroid cancer incidence, insurance and census tract SES during 2007–2010 were examined in population-based cancer registries. Cases were stratified by tumour histology, size and demography.

Setting

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries covering 30% of the US population.

Results

PTCs accounted for 88% of incident thyroid cancer cases. Small PTCs (≤2 cm) accounted for 60% of cases. Unlike non-PTC cases, the majority of those diagnosed with PTC were <50 years of age and had ≤2 cm tumours. Rate ratios (RR) of PTC diagnoses increased monotonically with SES among fully insured cases. The effect was strongest for small PTCs, high-SES versus low-SES quintile RR=2.7, 95% CI 2.6 to 2.9, two-sided trend test p<0.0001. For small PTC cases with insurance, the monotonic increase in incidence rates with rising SES persisted among cases younger than 50 years of age (RR=3.3, 95% CI 3.0 to 3.5), women (RR=2.6, 95% CI 2.5 to 2.8) and Caucasians (RR=2.5, 95% CI 2.4 to 2.7). Among the less than fully insured, rates generally decreased with increasing SES.

Conclusions

The >2.5-fold increase in risk of PTC diagnosis among insured individuals associated with high SES may be informative with respect to the contemporary issue of PTC overdiagnosis.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study included 41 072 incident thyroid cancer cases during 2007–2010 across 30% of the US population.

Rate ratios and CIs were used to assess effects of socioeconomic status and insurance on thyroid cancer incidence.

Effects were also examined by patient attributes, tumour size and histology.

Potential misclassification of histology data from population-based pathology reports was a limitation of this study.

Introduction

In Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry areas of the USA from 1975 to 2011, thyroid cancer incidence rates tripled1–3 while US thyroid cancer mortality trends were steady.1 These discrepant trends are consistent with cancer overdiagnosis.2–4 Similar patterns are reported in many but not all industrialised countries.3 Thyroid cancer incidence rates are higher among women than men5 and among Caucasians than other major racial groups.6 7 Most of the rising incidence results from the increasing diagnosis of small papillary thyroid cancers (PTCs).2–4 8–10

Access to health insurance contributes to the overdiagnosis of small PTCs,3 11–13 which carries a relatively low risk of death.3 Incidence rates of small PTCs are elevated in high socioeconomic status (SES) counties7 14 15 and census tracts.11 12 Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of PTCs are associated with adverse effects, including postsurgical complications, extended hospitalisation and lifelong hormone replacement therapy.2–4 16 In contrast, several non-PTC types, including follicular, medullary and anaplastic thyroid cancers, carry progressively worse prognoses.17 The present analysis, based on population-level cancer registry data covering approximately 30% of the USA, demonstrates the magnitude of combined effects of neighbourhood SES,18 19 and personal insurance status on the overdiagnosis of small PTCs including by age, gender, race and ethnicity.

Materials and methods

Data were obtained from 16 National Cancer Institute (NCI) SEER registries that cover approximately 30% of the US population. The SEER November 2012 data set was used for all analyses. Registries included in analyses were Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, San Francisco-Oakland, Atlanta, Iowa, New Mexico, Seattle-Puget Sound, Utah, Los Angeles, San Jose-Monterey, Rural Georgia, Greater California, Greater Georgia, Kentucky and New Jersey. Alaska Native cases were excluded because census tract attributes were not available, and Louisiana cases were excluded because of uncertainty about the population impact of Hurricane Katrina on census tract SES.

Case attributes

Gender and age distributions (<50, 50–64 and ≥65 years of age at diagnosis) were examined. While 98% of cases were 20 years of age and older at time of diagnosis, the analysis included children <20 years of age for purpose of completeness. Race and ethnicity were defined as Hispanic, non-Hispanic Caucasians, non-Hispanic African-Americans, and non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander. Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Natives and other and unknown races were combined as one group. Tumours were classified as ≤2, >2 cm and unknown size. When ≤10 cases were observed, data were suppressed.

Histological classification

Only malignant primary thyroid cancers were included in analyses. Thyroid cancer histological classifications were coded using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3).20 A total of 283 cases with poorly specified cancer histologies (ICD-O-3 morphologies 8000–8005) were excluded. ICD-O-3 histology codes for PTC were 8050, 8052, 8260, 8340, 8341, 8342, 8343, 8344. Other types were follicular (8290, 8330, 8331, 8332, 8335), medullary (8290, 8330, 8331, 8332, 8335) and anaplastic thyroid cancer (8012, 8020–8021, 8030–8032). Approximately 2% of cases were diagnosed with non-classical thyroid cancer histologies including 284 cases (1%) with other epithelial neoplasms (8010, 8013, 8015, 8022, 8033, 8035, 8041, 8046) and 377 cases (1%) with other rare specified primary thyroid cancer histologies (8070–8072, 8074, 8082–8083, 8130, 8140–8141, 8190, 8200–8201, 8230, 8240, 8246, 8255, 8262–8263, 8310, 8323, 8337, 8347, 8350, 8430, 8450, 8452, 8460, 8480–8481, 8504, 8507, 8560, 8570, 8588–8589, 8800, 8802, 8810, 8830, 8890, 8980, 9040–9041, 9071, 9080, 9120, 9250, 9364). These included adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinoma, which are referenced on the SEER thyroid/histology validation list,21 and other specified histologies that are not found in the SEER validation list but were abstracted from patients’ medical records.

Insurance

SEER data include the six category variable ‘Insurance Recode’ for the diagnosis year 2007 forward, derived from the more detailed ‘Primary Payer at Diagnosis’ variable. For the purpose of the present analysis, categories were collapsed into ‘Fully Insured’ and ‘Other than Fully Insured’. ‘Fully Insured’ is defined by the following seven categories of health insurance: (1) Insured—Private Insurance: Fee-for-Service, (2) Private Insurance: Managed care, (3) Health Maintenance Organisation or Preferred Provider Organisation, (4) TRICARE, (5) Medicare—Administered through a Managed Care plan, (6) Medicare with a private supplement and (7) Medicare with supplement, not otherwise specified and Military. ‘Other than Fully Insured’ included (1) Uninsured cases; (2) Cases with Medicaid, Indian Health Service insurance and (3) Patients reported to be insured without further information available. The 1228 cases with missing data on insurance status were excluded from insurance-related analyses.

Census-tract level SES

SES is typically measured using county-level attributes as a proxy for individual data. However, county-level SES attributes are less precise than smaller area or individual SES attributes. To improve area-based SES estimates, we used a year-dependent census tract SES composite index18 linked to SEER cases by the census tracts of residence at time of diagnosis. The SES index was derived from seven variables (per cent working class population, per cent adult unemployment, educational attainment, median household income, per cent of population living below 150% of national poverty line, median rent and median home value). Taken together, these variables capture three principal components of SES (income, occupation, education). The weight assigned to each variable was determined on the basis of factor analysis.18 Specifically, the output from factor analysis that explained more than 90% of the common variance among these variables was used as the ‘SES index’. This index was constructed separately for 2007, 2008, 2009 and 2010 using the 5-year estimates from the 2005–2009, 2006–2010, 2007–2011 and 2008–2012 American Community Surveys, respectively. Census tracts were categorised into SES quintiles according to this index, with equal populations in each quintile. The first quintile (Q1, lowest SES) is the 20th centile or less, and the fifth quintile (Q5, highest SES) corresponds to the 80th centile or higher. The SES index used in the present study has the advantage over specific area level SES measures of protecting against disclosure of case identity through identification of any census tract with a unique permutation of multiple SES attributes. The index is linked to standard SEER data and is available for public use on request from the authors. A total of 642 cases were missing data on SES and were excluded from SES-related analysis.

Incidence by insurance and SES

Age-adjusted incidence rates22 were calculated by tumour size, insurance status, SES and histology for cases diagnosed during 2007–2010, years during which insurance data were available (SEER Stat V.8.1.5, IMS, Inc, Calverton, Maryland, USA). Thyroid cancer incidence rates per 100 000 persons were directly age-adjusted to the 2000 US population. Rate ratios (RR) and 95% CIs were calculated using the SES lowest quintile as the reference. Regression models were used to estimate the percentage change in rate by SES23 for PTC and non-PTC histologies using the SAS PROC REG procedure (SAS 9.3, Cary, North Carolina, USA). The regression line slope was considered to be statistically different from zero at a cut-off of p≤0.05 based on a two-sided test.

Results

Demographics

Characteristics of patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer during 2007–2010 are shown in table 1. The 41 072 cases were diagnosed with the following subtypes: 36 020 papillary (88%), 3288 follicular (8%), 722 medullary (2%), 381 anaplastic (1%), 284 other epithelial (1%) and 377 other histologies (1%). Half of the cases (49%) were <50 years of age, including 51% of PTC cases. Most cases in other histological groups were 50 years of age or older. Women accounted for 76% of cases and 77% of PTC cases. Asians/Pacific Islanders accounted for a high proportion of anaplastic tumours (13%), while African-Americans accounted for a high proportion of follicular, medullary (9% each) and other epithelial tumours (10%). Among Caucasians and Hispanics, subtype distributions were similar to overall thyroid cancer case distributions. Most PTCs (69%) were ≤2 cm (small PTCs). Small PTCs accounted for 24 745 of all 41 072 thyroid cancer cases (60%). Most follicular thyroid (69%) and most anaplastic thyroid cancer (76%) tumours were >2 cm in size. PTC cases had the highest percentage of full insurance coverage (74%). The percentage of full insurance coverage ranged from 60% for anaplastic and other epithelial to 72% for follicular cancer cases. Insurance data were missing for 3% of cases. Analysis of SES was based on 40 430 cases, with missing SES data for 642 cases. Case counts increased with SES for each subtype, doubling for PTC from quintiles 1 to 5, increasing by 60% for follicular, 31% for medullary, 49% for anaplastic, 29% for other epithelial and 67% for other specified cancers.

Table 1.

Characteristics of thyroid cancer cases by histological group, SEER registries 2007–2010*

| Histology groups |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papillary |

Follicular |

Medullary |

Anaplastic |

Other epithelial |

Other specified |

Total |

||||||||

| N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | |

| Diagnosis age (years) | ||||||||||||||

| <50 | 18 358 | 51 | 1333 | 41 | 279 | 39 | 20 | 5 | 65 | 23 | 136 | 36 | 20 191 | 49 |

| 50–64 | 11 603 | 32 | 1026 | 31 | 238 | 33 | 90 | 24 | 67 | 24 | 117 | 31 | 13 141 | 32 |

| 65+ | 6059 | 17 | 929 | 28 | 205 | 28 | 271 | 71 | 152 | 54 | 124 | 33 | 7740 | 19 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 27 906 | 77 | 2304 | 70 | 445 | 62 | 233 | 61 | 186 | 65 | 257 | 68 | 31 331 | 76 |

| Male | 8114 | 23 | 984 | 30 | 277 | 38 | 148 | 39 | 98 | 35 | 120 | 32 | 9741 | 24 |

| Race/ethnicity† | ||||||||||||||

| Caucasian† | 24 285 | 67 | 2241 | 68 | 494 | 68 | 264 | 69 | 182 | 64 | 251 | 67 | 27 717 | 67 |

| Hispanic | 5540 | 15 | 412 | 13 | 108 | 15 | 45 | 12 | 34 | 12 | 47 | 12 | 6186 | 15 |

| API† | 3684 | 10 | 264 | 8 | 35 | 5 | 51 | 13 | 32 | 11 | 34 | 9 | 4100 | 10 |

| African-American† | 1930 | 5 | 312 | 9 | 68 | 9 | 18 | 5 | 28 | 10 | 34 | 9 | 2390 | 6 |

| Other | 581 | 2 | 59 | 2 | 17 | 2 | * | * | * | * | 11 | 3 | 679 | 2 |

| Tumour size (cm) | ||||||||||||||

| ≤2 | 24 745 | 69 | 784 | 24 | 347 | 48 | * | * | * | * | 154 | 41 | 26 083 | 64 |

| >2 | 9907 | 28 | 2271 | 69 | 326 | 45 | 289 | 76 | 106 | 37 | 172 | 46 | 13 071 | 32 |

| Unknown | 1368 | 4 | 233 | 7 | 49 | 7 | 83 | 22 | 134 | 47 | 51 | 14 | 1918 | 5 |

| Insurance status | ||||||||||||||

| Fully insured | 26 800 | 74 | 2 366 | 72 | 497 | 69 | 227 | 60 | 169 | 60 | 265 | 70 | 30 324 | 74 |

| Uninsured | 847 | 2 | 83 | 3 | 27 | 4 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 985 | 2 |

| Any Medicaid | 2621 | 7 | 289 | 9 | 80 | 11 | 47 | 12 | 40 | 14 | 35 | 9 | 3112 | 8 |

| Insured, NOS | 4683 | 13 | 466 | 14 | 104 | 14 | 74 | 19 | 43 | 15 | 53 | 14 | 5423 | 13 |

| Unknown | 1069 | 3 | 84 | 3 | 14 | 2 | 23 | 6 | 24 | 8 | 14 | 4 | 1228 | 3 |

| Census tract SES | ||||||||||||||

| Q1 (low) | 4672 | 13 | 508 | 15 | 124 | 17 | 55 | 14 | 49 | 17 | 58 | 15 | 5466 | 13 |

| Q2 | 5904 | 16 | 579 | 18 | 133 | 18 | 73 | 19 | 61 | 21 | 74 | 20 | 6824 | 17 |

| Q3 | 7063 | 20 | 618 | 19 | 143 | 20 | 75 | 20 | 55 | 19 | 66 | 18 | 8020 | 20 |

| Q4 | 8134 | 23 | 721 | 22 | 151 | 21 | 88 | 23 | 47 | 17 | 79 | 21 | 9220 | 22 |

| Q5 (high) | 9685 | 27 | 811 | 25 | 162 | 22 | 82 | 22 | 63 | 22 | 97 | 26 | 10 900 | 27 |

| Unknown | 562 | 2 | 51 | 2 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 642 | 2 |

| Total | 36 020 | 88 | 3288 | 8 | 722 | 2 | 381 | 1 | 284 | 1 | 377 | 1 | 41 072 | 100 |

*SEER 18 registries excluding Louisiana and Alaska and 232 cases with poorly specified histologies. Case counts suppressed to conceal cells with 10 or fewer cases.

†Caucasian, African-American, and API exclude persons of Hispanic ethnicity.

API, Asian/Pacific Islander; NOS, not otherwise specified; Q, quintile; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; SES, socioeconomic status.

Insurance and SES

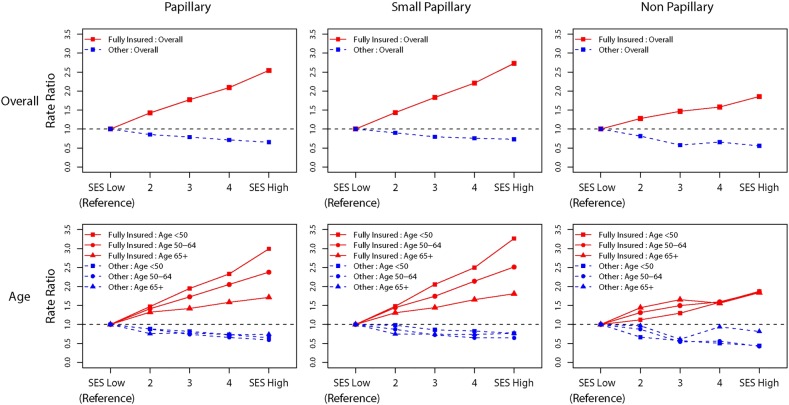

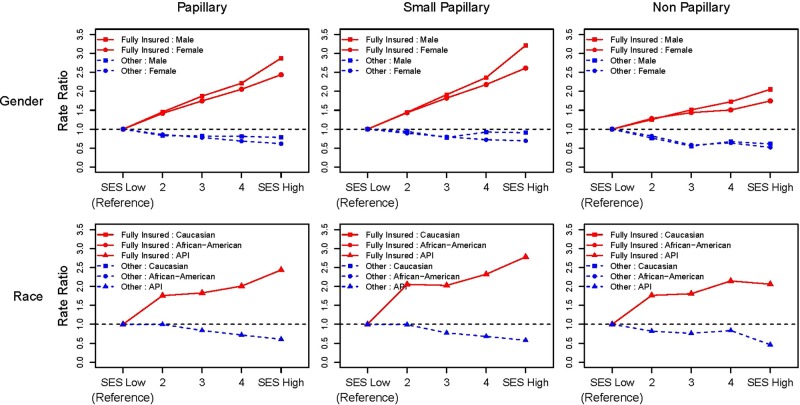

Among fully insured cases, RRs for PTC incidence increased monotonically with SES (table 2). The RR in the high compared to the low-SES stratum was 2.6 (95% CI 2.4 to 2.7), two-sided trend test of rate, p<0.0001. For small PTCs, this RR reached 2.7 (95% CI 2.6 to 2.9), two-sided trend test p<0.0001. Incidence rates for larger PTCs were lower than those for small PTCs and the dose–response with rising SES was attenuated compared to that for small PTCs. The monotonic increase in RR with increasing SES for PTC cases persisted for small PTCs including among persons <50 years of age, women and Caucasians (table 3). RRs associated with high-SES and insurance are shown in red while those of less than fully insured cases are shown in blue in figures 1 and 2. In addition to the overall effect among insured cases (figure 1), large increases in RRs with SES were seen among persons <50 years of age, men and Asians (figure 2). Among insured non-PTC cases, the increase in RRs with SES was less pronounced than among cases with PTCs, with follicular tumours accounting for 60% of non-PTCs. Among less than fully insured cases, rates did not increase with SES.

Table 2.

Papillary thyroid cancer incidence rates and RR by SES and tumour size among fully insured cases, SEER registries, 2007–2010*

| SES | All cases |

≤2 cm tumours |

>2 cm tumors |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Rate‡ | RR | 95% CI | N | Rate | RR | 95% CI | N | Rate | RR | 95% CI | |

| 26 392 | 18 539 | 6774 | ||||||||||

| Q1 (low) | 2664 | 4.6 | 1.0 | (Referent) | 1778 | 3.1 | 1.0 | (Referent) | 484 | 1.3 | 1.0 | (Referent) |

| Q2 | 4045 | 6.5 | 1.4 | (1.4 to 1.5) | 2722 | 4.4 | 1.4 | (1.3 to 1.5) | 1205 | 1.9 | 1.5 | (1.3 to 1.6) |

| Q3 | 5248 | 8.1 | 1.8 | (1.7 to 1.9) | 3643 | 5.6 | 1.8 | (1.7 to 1.9) | 1457 | 2.3 | 1.7 | (1.6 to 1.9) |

| Q4 | 6425 | 9.6 | 2.1 | (2.0 to 2.2) | 4573 | 6.8 | 2.2 | (2.1 to 2.3) | 1670 | 2.5 | 1.9 | (1.7 to 2.1) |

| Q5 (high) | 8011 | 11.6 | 2.6 | (2.4 to 2.7) | 5823 | 8.4 | 2.7 | (2.6 to 2.9) | 1958 | 2.9 | 2.2 | (2.0 to 2.4) |

| Trend for SES | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.002 | |||||||||

*SEER 18 excluding Alaska and Louisiana and cases with unknown SES.

†Fully insured: private insurance; Fee-for-Service; Private Insurance: Managed care, Health Maintenance Organisation, or Preferred Provider Organisation; TRICARE; Medicare Administered through a Managed Care plan; Medicare with private supplement; Medicare with supplement, not otherwise specified; and Military; Other: Uninsured; Any Medicaid; Insured, No Specifics; and Insurance status unknown (SEER Nov 2012 Submission).

‡Age-adjusted rates adjusted to the 2000 US standard population.22

Q, quintile; RR, rate ratio; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; SES, socioeconomic status.

Table 3.

Papillary thyroid cancer incidence rates and rate ratios by SES, age, race and gender among fully insured cases with ≤2 cm tumours, SEER registries, 2007–2010*

| Attribute | Group/trend for SES | SES | Count | Rate | Rate ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||||||

| 00–49 years | ||||||

| p=0.0003 | Q1 (low) | 850 | 2.0 | 1.0 | (Ref) | |

| Q2 | 1298 | 3.0 | 1.5 | (1.4 to 1.6) | ||

| Q3 | 1833 | 4.2 | 2.1 | (1.9 to 2.2) | ||

| Q4 | 2289 | 5.1 | 2.5 | (2.3 to 2.7) | ||

| Q5 (high) | 2955 | 6.7 | 3.3 | (3.0 to 3.5) | ||

| 50–64 years | ||||||

| p<0.0001 | Q1 (low) | 596 | 6.2 | 1.0 | (Ref) | |

| Q2 | 933 | 8.9 | 1.4 | (1.3 to 1.6) | ||

| Q3 | 1229 | 10.7 | 1.7 | (1.6 to 1.9) | ||

| Q4 | 1606 | 13.2 | 2.1 | (2.0 to 2.4) | ||

| Q5 (high) | 2084 | 15.6 | 2.5 | (2.3 to 2.8) | ||

| 65+ years | ||||||

| p=0.0008 | Q1 (low) | 332 | 5.2 | 1.0 | (Ref) | |

| Q2 | 491 | 6.8 | 1.3 | (1.1 to 1.5) | ||

| Q3 | 581 | 7.5 | 1.5 | (1.3 to 1.7) | ||

| Q4 | 678 | 8.6 | 1.7 | (1.5 to 1.9) | ||

| Q5 (high) | 784 | 9.5 | 1.8 | (1.6 to 2.1) | ||

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasians | ||||||

| p<0.0001 | Q1 (low) | 1416 | 3.5 | 1.0 | (Ref) | |

| Q2 | 2245 | 4.7 | 1.3 | (1.2 to 1.4) | ||

| Q3 | 3096 | 6.0 | 1.7 | (1.6 to 1.8) | ||

| Q4 | 3883 | 7.2 | 2.1 | (1.9 to 2.2) | ||

| Q5 (high) | 4891 | 8.8 | 2.5 | (2.4 to 2.7) | ||

| African-Americans | ||||||

| p=0.0025 | Q1 (low) | 247 | 1.9 | 1.0 | (Ref) | |

| Q2 | 198 | 2.6 | 1.3 | (1.1 to 1.6) | ||

| Q3 | 181 | 3.0 | 1.5 | (1.3 to 1.9) | ||

| Q4 | 147 | 3.4 | 1.8 | (1.4 to 2.2) | ||

| Q5 (high) | 117 | 4.5 | 2.3 | (1.8 to 2.9) | ||

| Asian | ||||||

| p=0.0199 | Q1 (low) | 84 | 2.4 | 1.0 | (Ref) | |

| Q2 | 248 | 4.9 | 2.1 | (1.6 to 2.7) | ||

| Q3 | 312 | 4.8 | 2.0 | (1.6 to 2.6) | ||

| Q4 | 478 | 5.5 | 2.3 | (1.8 to 3.0) | ||

| Q5 (high) | 716 | 6.6 | 2.8 | (2.2 to 3.5) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | ||||||

| p=0.0014 | Q1 (low) | 318 | 1.1 | 1.0 | (Ref) | |

| Q2 | 491 | 1.7 | 1.4 | (1.2 to 1.7) | ||

| Q3 | 689 | 2.2 | 1.9 | (1.7 to 2.2) | ||

| Q4 | 888 | 2.7 | 2.4 | (2.1 to 2.7) | ||

| Q5 (high) | 1266 | 3.7 | 3.2 | (2.8 to 3.7) | ||

| Female | ||||||

| p<0.0001 | Q1 (low) | 1460 | 4.9 | 1.0 | (Ref) | |

| Q2 | 2231 | 7.0 | 1.4 | (1.3 to 1.5) | ||

| Q3 | 2954 | 8.9 | 1.8 | (1.7 to 1.9) | ||

| Q4 | 3685 | 10.7 | 2.2 | (2.1 to 2.3) | ||

| Q5 (high) | 4557 | 12.8 | 2.6 | (2.5 to 2.8) | ||

*SEER 18 excluding Alaska and Louisiana and cases with unknown SES.

†Fully Insured: Private Insurance; Fee-for-Service; Private Insurance: Managed care, Health Maintenance Organisation, or Preferred Provider Organisation; TRICARE; Medicare Administered through a Managed Care plan; Medicare with private supplement; Medicare with supplement, not otherwise specified; and Military; Other: Uninsured; Any Medicaid; Insured, No Specifics; and Insurance status unknown (SEER Nov 2012 Submission).

‡Age-adjusted rates adjusted to the 2000 US standard population.22

Q, quintile; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; SES, socioeconomic status.

Figure 1.

Overall and age-specific thyroid cancer rate ratios by socioeconomic status and insurance status for papillary thyroid cancers (PTC) and other histologies with stratification of PTCs <2 cm in size—Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries, 2007–2010 (SEER 18 excluding Louisiana and Alaska cases and 283 cases with unspecified histologies (ICD-O-3 8000–8005)).

Figure 2.

Gender-specific and race-specific thyroid cancer rate ratios by SES and insurance status for papillary thyroid cancers (PTC) and other histologies with stratification of PTCs <2 cm in size— Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries, 2007–2010. (SEER 18 excluding Louisiana and Alaska cases and 283 cases with unspecified histologies (ICD-O-3 8000–8005) (API, Asian/Pacific Islander; SES, socioeconomic status).

Discussion

In this SEER study among fully insured cases, risk of PTC diagnosis increased monotonically with SES. This association was driven by diagnosis of small PTCs, with a 2.7-fold higher rate in the highest compared to the lowest SES quintile. The effect persisted within several subgroups including persons <50 years of age, women and white. These overlapping subgroups comprise a large proportion of all cases, with large numbers of participants in each SES stratum. Among the ‘other than fully insured’, a more heterogeneous group including Medicaid and uninsured patients, thyroid cancer incidence did not increase with SES. The enumeration of risk among insured cases in high compared to low-SES areas may inform current discussions pertaining to PTC overdiagnosis.

This study is a large SEER population-based study, covering 30% of the population, with both census tract SES and individual insurance data. The results are more detailed than previous studies of thyroid cancer incidence and SES3 7 11–15 24 or health insurance coverage12–15 with findings that differ from early studies that found no association with SES or insurance.25 26 Our study and a New Jersey study spanning 1979–200612 include census tract-level SES. The New Jersey study included county-level insurance data, while this study is based on individual-level insurance data. This is the first report of which we are aware to report a monotonic increase in PTC incidence rates with rising SES among insured cases. Our findings further indicate that this effect is largely driven by the diagnosis of small PTCs.

The rising incidence of small PTCs is described as an epidemic of diagnosis,2–4 disproportionately affecting women4 5 11 12 and patients under 50 years of age.5 Among insured cases, the effect of SES on risk of small PTC diagnosis was most pronounced among persons <50 years of age. There is a need to determine why people in this age stratum and other at-risk groups including women and Caucasians are more likely to undergo tests that lead to the diagnosis of PTC. Although small PTCs accounted for 60% of thyroid cancer cases in this report, previous studies indicate that PTCs account for <5% of thyroid cancer deaths and that other thyroid cancer types carry far worse prognoses.17 The higher incidence of PTC among insured individuals residing in high-SES areas could be a consequence of higher paid individuals being ‘overinsured’ relative to lower paid ‘underinsured’ workers.27 Overinsurance could increase access to imaging and biopsy for cancer screening and evaluation of benign thyroid conditions. Such technologies may detect small, relatively low-risk thyroid nodules.2 4 In one study, areas with high numbers of young physicians reported increased incidence rates of thyroid cancer compared to areas with high concentrations of older physicians.28 The authors postulated that there is greater use of ultrasound-guided biopsy by young physicians trained in this technology. If these diagnostic resources are more likely to be found in high-SES areas, it could contribute to associations between affluence and PTC incidence. Other potential explanations include that income and insurance are proxy measures for education. To the extent that this is the case, more educated individuals may seek early care and press their physicians for specific thyroid-related tests and treatments.

Unless needed, postdiagnosis thyroidectomy and radiation place patients with small PTCs at risk for avoidable surgical complications, lifetime thyroid replacement therapy and perhaps second malignancies.2–4 The cost of care for US patients diagnosed with well-differentiated thyroid cancer exceeded US$1.6 billion in 2013 alone, including more than US$0.5 billion each for initial treatment and continued follow-up.29 American Thyroid Association (ATA) Management guidelines30 for patients with thyroid nodules encourage non-invasive management unless patients have risk factors such as a family history of thyroid cancer, specific medical or environmental radiation exposures, or rapid tumour growth with hoarseness. One recent study estimated that, in the USA, approximately 82 000 men and women were diagnosed with PTCs during 1981–2011 that would never cause symptoms.31 It has been proposed that some small PTCs be reclassified as non-cancers2 3 10 or that the most biologically indolent tumours be managed with watchful waiting.2–4 Reclassifying any PTCs as non-cancerous would affect cancer survival statistics,32 because thyroid cancer survival is known to vary by stage, age, gender and treatment.33 Biomarker research may also help to distinguish thyroid cancers including PTCs that are likely to exhibit aggressive behaviour from other, more indolent types.34

The strengths of this study include the availability of SEER variables for census tract SES and individual insurance status in registries covering 30% of the US population. Most studies of thyroid cancer incidence and SES3 7 11 13–15 24 have measured SES at the county or registry level. Study limitations include potential misclassification of histology and availability of insurance data only for four recent years. In summary, compared to persons with insurance living in low-SES areas, those from high-SES areas had more than a 2.5-fold higher risk of being diagnosed with PTC. The association was driven by small PTCs and persisted among persons younger than 50 years, women and Caucasians. Quantifying the risk of PTC associated with SES and insurance may inform efforts to prevent overdiagnosis.

Footnotes

Contributors: SA and MY were responsible for design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting and revising for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of any part of the work. AD was involved in design, acquisition and interpretation of data; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of any part of the work. HC was responsible for design, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting and revising of content; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of any part of the work. VP was involved in analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting and revising of content; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of any part of the work.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The SES index used in this report is linked to the SEER public research data set and is available from the authors on review of request.

References

- 1.NCI. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2011. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/ (accessed 7 Oct 2014).

- 2.Davies L, Welch HG. Current thyroid cancer trends in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;140:317–22. 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brito JP, Morris JC, Montori VM. Thyroid cancer: zealous imaging has increased detection and treatment of low risk tumours. BMJ 2013;347:f4706 10.1136/bmj.f4706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies L, Welch HG. Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States, 1973–2002. JAMA 2006;295:2164–7. 10.1001/jama.295.18.2164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kilfoy BA, Devesa SS, Ward MH et al. Gender is an age-specific effect modifier for papillary cancers of the thyroid gland. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:1092–100. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Ward MH, Sabra MM et al. Thyroid cancer incidence patterns in the United States by histologic type, 1992–2006. Thyroid 2011;21:125–34. 10.1089/thy.2010.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris LG, Sikora AG, Myssiorek D et al. The basis of racial differences in the incidence of thyroid cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:1169–76. 10.1245/s10434-008-9812-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pacini F, Castagna MG. Approach to and treatment of differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Med Clin North Am 2012;96:369–83. 10.1016/j.mcna.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kent WD, Hall SF, Isotalo PA et al. Increased incidence of differentiated thyroid carcinoma and detection of subclinical disease. CMAJ 2007;177:1357–61. 10.1503/cmaj.061730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.How J, Tabah R. Explaining the increasing incidence of differentiated thyroid cancer. CMAJ 2007;177:1383–4. 10.1503/cmaj.071464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haselkorn T, Bernstein L, Preston-Martin S et al. Descriptive epidemiology of thyroid cancer in Los Angeles County, 1972–1995. Cancer Causes Control 2000;11:163–70. 10.1023/A:1008932123830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roche LM, Niu X, Pawlish KS et al. Thyroid cancer incidence in New Jersey: time trend, birth cohort and socioeconomic status analysis (1979–2006). J Environ Public Health 2011;2011:850105 10.1155/2011/850105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris LG, Sikora AG, Tosteson TD et al. The increasing incidence of thyroid cancer: the influence of access to care. Thyroid 2013;23:885–91. 10.1089/thy.2013.0045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li N, Du XL, Reitzel LR et al. Impact of enhanced detection on the increase in thyroid cancer incidence in the United States: review of incidence trends by socioeconomic status within the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry, 1980–2008. Thyroid 2013;23:103–10. 10.1089/thy.2012.0392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sprague BL, Warren Andersen S, Trentham-Dietz A. Thyroid cancer incidence and socioeconomic indicators of health care access. Cancer Causes Control 2008;19:585–93. 10.1007/s10552-008-9122-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sisson JC. Medical treatment of benign and malignant thyroid tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1989;18:359–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu GP, Li JC, Branovan D et al. Thyroid cancer incidence and survival in the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results race/ethnicity groups. Thyroid 2010;20:465–73. 10.1089/thy.2008.0281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu M, Tatalovich Z, Gibson JT et al. Using a composite index of socioeconomic status to investigate health disparities while protecting the confidentiality of cancer registry data. Cancer Causes Control 2014;25:81–92. 10.1007/s10552-013-0310-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yost K, Perkins C, Cohen R et al. Socioeconomic status and breast cancer incidence in California for different race/ethnic groups. Cancer Causes Control 2001;12:703–11. 10.1023/A:1011240019516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Percy C, Fritz A, Jack A et al., eds International classification of diseases for oncology (ICD-O). 3rd edn Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.NCI. ICD-O-3 SEER Site/Histology Validation List http://seer.cancer.gov/icd-o-3/ (accessed 30 Jun 2015).

- 22.National Cancer Institute. Standard Populations (Millions) for Age-Adjustment Website. 2013. http://seer.cancer.gov/stdpopulations/ (accessed 7 Oct 2014).

- 23.Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research. Volume II-The design and analysis of cohort studies. IARC Sci Publ 1987;(82):1–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall SF, Irish J, Groome P et al. Access, excess, and overdiagnosis: the case for thyroid cancer. Cancer Med 2014;3:154–61. 10.1002/cam4.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haselkorn T, Stewart SL, Horn-Ross PL. Why are thyroid cancer rates so high in Southeast Asian women living in the United States? The Bay Area thyroid cancer study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2003;12:144–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolonel LN, Hankin JH, Wilkens LR et al. An epidemiologic study of thyroid cancer in Hawaii. Cancer Causes Control 1990;1:223–34. 10.1007/BF00117474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robertson CT. Scaling cost-sharing to wages: how employers can reduce health spending and provide greater economic security. Yale J Health Policy Law Ethics 2014;14:239–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagar S, Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Kaplan EL et al. Age of diagnosing physician impacts the incidence of thyroid cancer in a population. Cancer Causes Control 2014;25:1627–34. 10.1007/s10552-014-0467-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lubitz CC, Kong CY, McMahon PM et al. Annual financial impact of well-differentiated thyroid cancer care in the United States. Cancer 2014;120:1345–52. 10.1002/cncr.28562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR et al. , American Thyroid Association (ATA) Guidelines Taskforce on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2009;19:1167–214. 10.1089/thy.2009.0110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Grady TJ, Gates MA, Boscoe FP. Thyroid cancer incidence attributable to overdiagnosis in the united states 1981–2011. Int J Cancer 2015;137:2664–73. 10.1002/ijc.29634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ho AS, Davies L, Nixon IJ et al. Increasing diagnosis of subclinical thyroid cancers leads to spurious improvements in survival rates. Cancer 2015;121:1793–9. 10.1002/cncr.29289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banerjee M, Muenz DG, Worden F et al. Conditional survival in thyroid cancer patients. Thyroid 2014;24:1784–9. 10.1089/thy.2014.0264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baldini E, Sorrenti S, Tuccilli C et al. Emerging molecular markers for the prognosis of differentiated thyroid cancer patients. Int J Surg 2014;12(Suppl 1):S52–6. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.05.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]