The current issue of the Journal of ExtraCorporeal Technology (JECT) includes three articles dealing with in vitro measurement of gaseous microemboli (GME) (1–3). A 1983 editorial by Butler was featured as a 2006 JECT Classic Article and would be an exceptional fundamental review for readers prior to reading the new JECT articles (4,5). The selection and discussion of the highly referenced Sakauye Classic builds on the information provided by Butler. Sakauye’s work set the stage for several GME papers the following years in JECT.

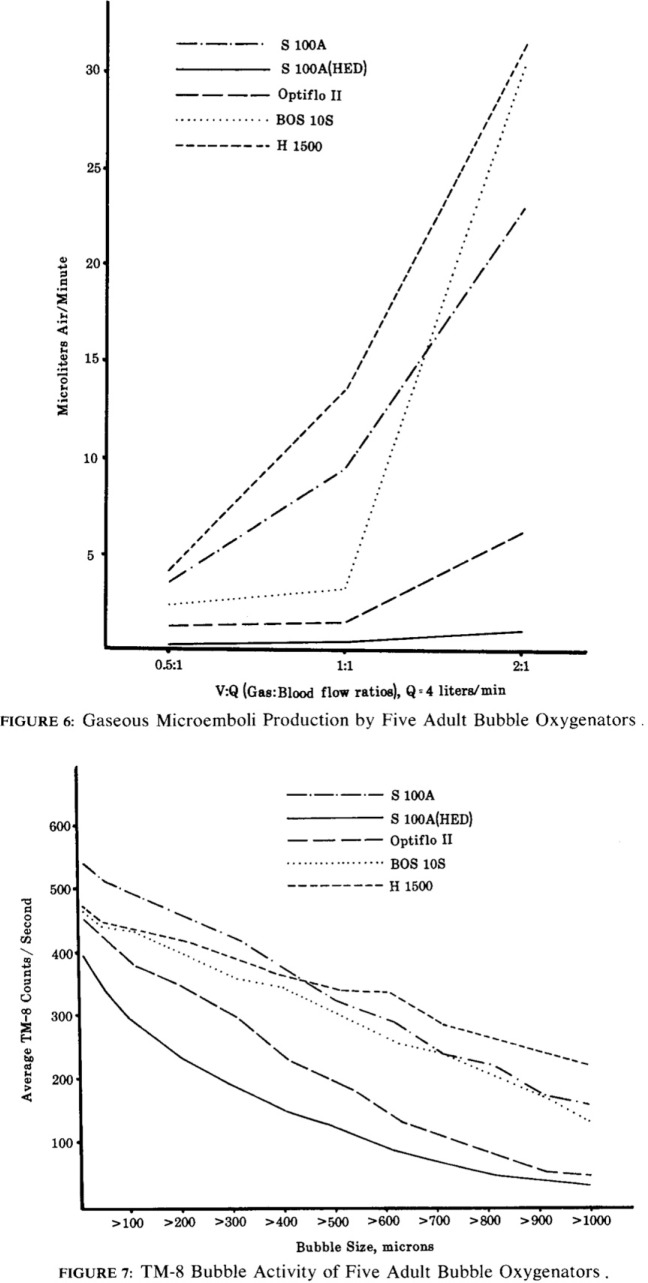

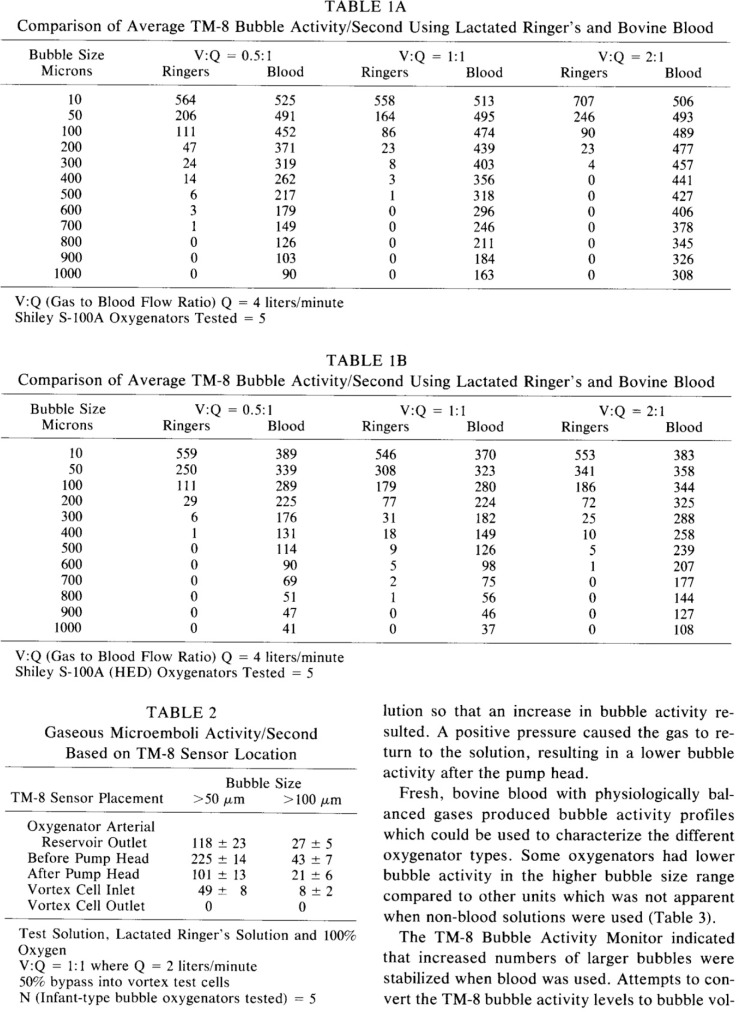

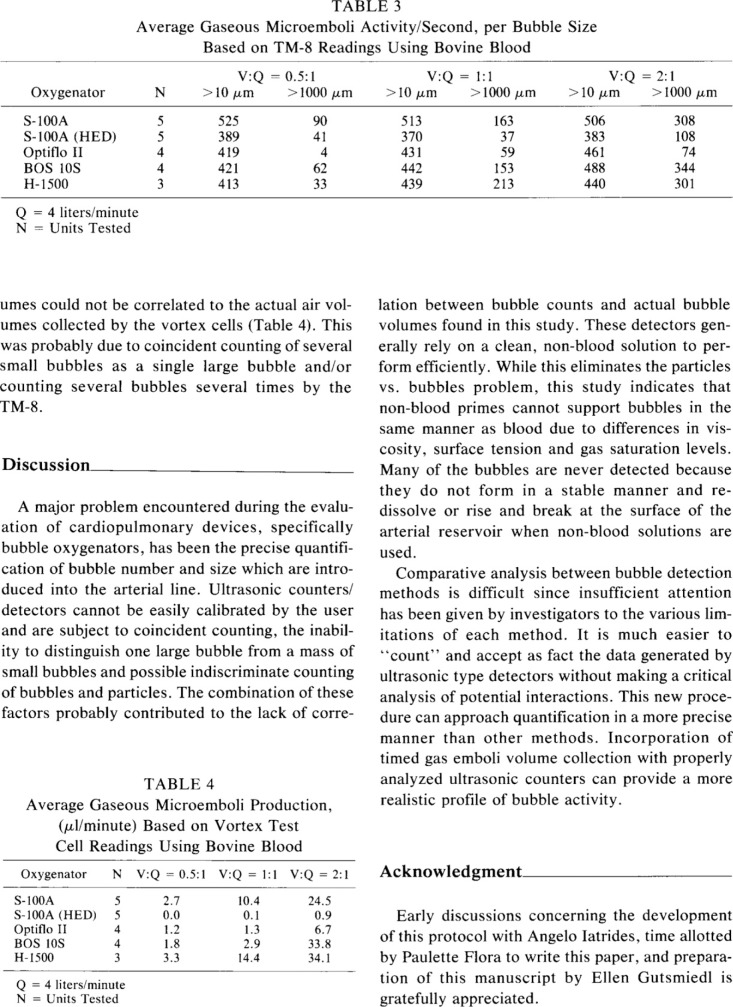

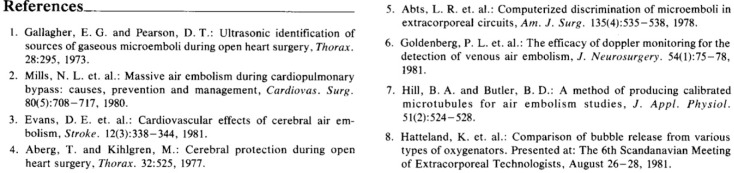

In their unique article, Sakauye et al. compare an ultrasonic bubble detector to a chamber especially designed to trap and coalesce micro air. They take on the issue of calibrating ultrasonic detectors. It is interesting that by 1983, we had known most of what we needed to know about measuring GME in flowing blood. The Sakauye team reminds us to not make assumptions about the calibration and validation of GME measurement systems. The information is in the volume of GME propelled as much as the GME counts at various sizes.

Why all the interest in GME measurement now and what is the motivation for the numerous abstracts and publications in the last 3 years? We have learned that we are continually pumping air to our patients and we want to know how to minimize the embolic load. We hope that minimizing the load will lead to better cerebral protection outcomes. We have articles since 1982 instructing us on the sources of GME into and out of the extracorporeal circulation with recommendations to reduce the embolic load.

Two clinical questions still plague us: 1) how large is the embolic load during cardiopulmonary bypass, and 2) what load threshold is detrimental to cardiopulmonary bypass patients? There is progress. The availability of consistent gaseous microemboli detectors has helped advance our knowledge about GME levels from extracorporeal circuit components used in clinical configurations. There is little data to show calibration methods for the GME detectors.

Compared to bubble oxygenators in the 1980s, our circuits and components today produce less and trap more GME, and the embolic load to cardiac patients is decreased. Thankfully, our device manufacturer partners have invested in GME detection systems and have made significant improvements to components. The new circuit designs and components need to be studied and ranked within the context of our two clinical questions regarding embolic load.

A search for the term “emboli” in the Journal of ExtraCorporeal Technology yields 60 articles, some published as early as 1975. Nineteen of these articles deal with GME. JECT papers reporting the measurement of reflected sound signals in flowing blood proportional to gaseous microemboli numbers and diameter were published in the early 1980s. The three GME measurement articles in this issue of JECT help advance our knowledge of potential circuit embolic loads during patient use.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liu S, Newland RF, Tully PJ, Tuble SC, Baker RA.. In vitro evaluation of gaseous microemboli handling of cardiopulmonary bypass circuits with and without integrated arterial line filters. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2011;43:107–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burnside J, Gomez D, Preston TJ, Olshove VF Jr, Phillips A.. In-vitro quantification of gaseous microemboli in two extracorporeal life support circuits. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2011;43:123–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potger KC, McMillan D, Ambrose M.. Microbubble generation and transmission of Medtronic’s Affinity hardshell venous reservoir and collapsible venous reservoir bag: An in-vitro comparison. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2011;43:115–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler B.. Gaseous microemboli: Concepts and considerations. J Extra Corpor Technol. 1983;15:145–155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riley J.. Classic Article: Gaseous Microemboli 1983. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2006;38:271–279. [Google Scholar]