Abstract

Objectives

The hypothesis of the study was that if the gut microbiota is involved in the development of atherosclerotic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (CVDs), total colectomy may reduce the long-term risk of CVDs. The aim was therefore to investigate the risk of CVD in patients after a total colectomy compared with patients undergoing other types of surgery, which are not expected to alter the gut microbiota or the CVD risk.

Setting

The Danish National Patient Register including all hospital discharges in Denmark from 1996 to 2014.

Participants

Patients (n=1530) aged 45 years and above and surviving 1000 days after total colectomy without CVDs were selected and matched with five control patients who were also free of CVD 1000 days after other types of surgery. The five control patients were randomly selected from each of the three surgical groups: orthopaedic surgery, surgery in the gastrointestinal tract leaving it intact and other surgeries not related to the gastrointestinal tract or CVD (n=22 950).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome was the first occurring CVD event in any of the seven diagnostic domains (hypertensive disorders, acute ischaemic heart diseases, chronic ischaemic heart disease, cardiac arrhythmias, heart failure, cerebrovascular diseases and other arterial diseases) and the secondary outcomes were the first occurring event within each of these domains.

Results

Estimated by Cox proportional hazard models, the HRs of the composite CVD end point for patients with colectomy compared with the control patients were not significantly reduced (HR=0.94, 95% confidence limits 0.85 to 1.04). Among the seven CVD domains, only the risk of hypertensive disorders was significantly reduced (HR=0.85, 0.73 to 0.98).

Conclusions

Colectomy did not reduce the general risk of CVD, but reduced the risk of hypertensive disorders, most likely due to salt and water depletion induced by colectomy. These results encourage a reappraisal of the associations between gut microbiota and CVD.

Keywords: VASCULAR MEDICINE, EPIDEMIOLOGY, colectomy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The major strength of the study is based on the availability of information in the entire Danish Patient Register from 1996 to 2014, which allows historical prospective assessment of the risk of new occurrences of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (CVDs) during long-term, essentially complete follow-up in patients after colectomy by comparison with matched patients that had undergone other types of surgery.

The nature and size of the study population provides adequate statistical power to detect any associations of CVD risk with colectomy of likely clinical relevance with little risk of biases, including confounding by indications for surgery.

The key limitations of the study with regard to appraisal of the causal role of the gut microbiota in development of CVDs are the necessity of using non-validated routine clinical diagnosis of CVDs reported at discharge from the hospitals, lack of information about risk factors for CVDs, and lack of information about the composition of the gut microbiota both before and after the surgery.

Introduction

While the host-microbial symbiosis may benefit both the microbiota and the human host,1–4 recent studies suggest that the gut microbiota is involved in the development of atherosclerotic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (CVDs).5–7 A harmful microbial composition, possibly combined with a disrupted intestinal barrier, may induce a state of intestinal dysbiosis leading to systemic inflammation, or specific bacterial fermentation.2 8–10 Increased lipopolysaccharide diffusion to the circulation through a disrupted intestinal barrier may lead to metabolic endotoxaemia which may induce systemic inflammation.1 11–13 A low-grade inflammatory origin of CVD has been suggested by previously observed elevated inflammatory markers among diseased individuals.1 11 14–17 Specific bacterial fermentation in the gut may lead to higher levels of trimethylamine-N-oxide, which has been suggested to promote atherogenesis.8–10 18 However, the direction of the causal relationship between the gut microbiota and the elevated risk of CVD is still unknown.8–10 12 19 As recently emphasised by Hanage,20 it is important to request evidence for changes in the risk of the presumed associated diseases by interventions affecting the gut microbiota.

Since the greatest part by far of the gut microbiota is carried in the colon, we suggest that patients who have had a total colectomy and have been carrying the overall harmful microbiota will benefit from the removal of the colon, whereas those carrying the beneficial microbiota will either not be affected by this procedure or be less likely to suffer from an increased CVD risk. The high frequency of CVD in the Western world may imply that a harmful gut microbiota is prevailing in this population. On this basis, we hypothesise that total colectomy in patients from this part of the world may be expected to reduce the CVD risk. To test this hypothesis, we compared the long-term occurrence of a panel of different CVD diagnoses in patients who have had a total colectomy with patients undergoing several other types of surgery not related to CVD and leaving the colon intact.

Methods

Population

For this study, we used the nationwide Danish National Patient Register covering all hospital contacts for patients from 1996 to 2014, during which period the discharge diagnoses were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10).21 There were a total of 88.8 million hospital encounters for 6.6 million patients in the data set. Within this data set, we identified those who have had total colectomy, and three series of control patients selected as described below. The outcome of interest was the occurrence of CVD diagnoses during the years after colectomy in patients who had not got a CVD diagnosis until surgery, or during a period of stabilisation following surgery. To optimise the comparability between the colectomy group and the control groups, we restricted the selection of control groups according to a set of selection criteria of presumed influence on the subsequently observed risk of CVD as explained in the following section.

Exposure and control groups

The colectomy group was selected according to the code JFH in the Scandinavian NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures,22 which covers total removal of the large intestine with or without ileostomy, hence without or with an ileorectal pouch, respectively. The control group was selected from the three groups of patients who had undergone other types of surgery: any orthopaedic surgery, any abdominal surgery leaving the colon intact, and other major surgeries, unrelated to the gastrointestinal tract or the cardiovascular and cerebrovascular system (see online supplementary table S1). To avoid the possible influence of morbidity and mortality related to the surgery as such, we defined the colectomy group and the control group as those who were alive and free of previous CVD diagnoses at 1000 days after colectomy and the corresponding time points in the control group, that is, 1000 days after surgery. The choice of 1000 days was based on the cumulative hazard plots of all-cause mortality for the colectomy group and the control group (see online supplementary figure S1); approximately until that point in time, the colectomy group had a much higher mortality, but thereafter the slopes of the cumulative hazards were stable in both groups, although still steadily higher in the colectomy group. During the available follow-up period, the younger patients are expected to have a rather low cumulative risk of CVD, and we therefore restricted the analyses to patients who had colectomy at the age of 45 years and above. For each of these patients with colectomy, five patients within each of the three surgical groups were matched by gender, date of birth (±12 months), date of surgery (±12 months) and otherwise randomly drawn from the patients fulfilling the selection criteria in the entire register population.

Colectomy subgroups

The underlying diseases for which colectomy was performed may influence the subsequent risk of CVD. Therefore, the analyses were repeated after dividing the patient group with colectomy and the matched control groups accordingly. One group included patients with colectomy with co-occurrence of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) at the time of surgery (n=791): Crohn's disease (K50), ulcerative colitis (K51), and other non-infective gastroenteritis and colitis (K52). The other group included patients with colectomy with a cancer diagnosis: any C-diagnoses in ICD-10 (n=531). Patients with cancer and IBD were present in both groups (n=41).

Primary and secondary CVD outcomes

Seven CVD domains, covering 32 different CVD diagnoses, were selected from the ICD-10 classification (see online supplementary table S2). They cover hypertensive diseases (ICD-10 codes I10 to I13), acute ischaemic heart diseases (I20, I21, I24, I46), chronic ischaemic heart disease (I23, I25, I51), cardiac arrhythmias (I44–I49), heart failure (I50), cerebrovascular diseases (I61 to I69) and other arterial diseases (I35, I70–I74). These diagnoses were included in a composite measure of the first occurring CVD diagnosis, which is considered as the primary end point. In supplementary analyses, the first occurring diagnosis within the seven CVD domains was investigated as well.

Statistical analyses

Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess the risk of CVD in the patients with colectomy compared with the risk of CVD in the control group from the 1000 days after the colectomy date and 1000 days after the date of surgery in the control group. Gender and age were included as covariates in the model. HRs with 95% confidence limits were estimated. Assessment of the assumption of proportional hazards in the Cox regression models with regard to estimates of the HR of CVDs for the colectomy group versus the control group showed no significant deviations.

The primary analysis was an estimation of the HR for CVD as a composite end point in the colectomy group compared to the control group. In additional analyses, the HRs of CVD within each of the seven CVD domains were evaluated, as were the HRs of CVD in stratified groups with co-occurring IBD and cancer. Patients were censored from the analyses either at the time of death or end of follow-up, but not at the occurrence of diagnoses from the other CVD groups when analysing the seven CVD domains.

Ethical considerations

This study is purely based on register-based data from the National Patient Register. Use of data has been approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency, Copenhagen (ref: 2010-54-1059) and the National Board of Health, Copenhagen (ref: 7-505-29-1624/1).

Results

Among the 5429 patients with colectomy aged 45 and above in the register, 2179 died before the 1000 days after surgery, and 659 had less than 1000 days of follow-up. Among the 2591 known to be alive 1000 days after surgery, CVD diagnoses were already made before the time of colectomy surgery among 690 patients, and CVD is present in 371 at the start of follow-up. Thus, the colectomy group at risk of first occurrence of CVD from 1000 days after surgery and onwards included 1530 patients. The control group matched to this colectomy group included 7650 patients from each of the three surgical subgroups, with 22 950 unique control patients included in the total. The average age of the included colectomy group at the date of surgery was 60.5 years, and 49% of them were men (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the colectomy as well as the matched control patients; the counts of the first CVD diagnosis, as well as CVD diagnoses within the seven CVD domains

| Patients with colectomy |

Control patients* |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | All (n=1530) | With IBD† (n=791) | With cancer (n=531) | All* (n=22 950) | Orthopaedic surgery (n=7650) | Surgery in the GI tract‡ (n=7650) | Other surgery not in the GI tract§ (n=7650) |

| Gender (% male) | 49.0 | 51.2 | 50.8 | 49.0 | 49.0 | 49.0 | 49.0 |

| Age (years), median (minimum, maximum) | 60 (45, 90) | 56 (45, 84) | 65 (45, 90) | 59 (45, 91) | 59 (45, 91) | 59 (45, 91) | 59 (45, 92) |

| Counts of the first CVD diagnosis¶ | 394 | 191 | 133 | 6564 | 2148 | 2223 | 2193 |

| CVD diagnosis domain (counts of first events) | |||||||

| Hypertensive disorders | 187 | 89 | 59 | 3474 | 1148 | 1166 | 1160 |

| Acute ischaemic heart diseases | 100 | 55 | 29 | 1751 | 568 | 596 | 587 |

| Chronic ischaemic heart disease | 63 | 33 | 21 | 1224 | 379 | 435 | 410 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 105 | 48 | 36 | 1854 | 607 | 647 | 600 |

| Heart failure | 57 | 27 | 18 | 841 | 273 | 310 | 258 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 85 | 34 | 34 | 1422 | 464 | 493 | 465 |

| Other arterial diseases | 65 | 33 | 22 | 1227 | 407 | 419 | 401 |

*Age and sex matched, but otherwise randomly selected control patients; five for each surgical comparison group of orthopaedic surgery, surgery in the GI tract, other major surgery not in the GI tract.

†IBD includes ulcerative colitis, patients with Crohn's disease and diagnoses of other non-infective gastroenteritis and colitis.

‡Leaving the gastrointestinal tract intact.

§Surgery not related to cardiac diseases.

¶First occurring cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diagnosis of 32 possible CVD diagnoses.

CVD, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular; GI, gastrointestinal; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Patients were followed for a total of 231 452 years with a mean follow-up time from the 1000 days and onwards of 9.0 and 9.5 years, respectively, for patients with colectomy and control patients. During follow-up, 25.8% of the patients with colectomy (n=394) had a CVD diagnosis, compared to 28.6% of control patients (n=6564). Table 1 shows the distribution of CVD diagnoses in the seven domains and across the colectomy group and the control group.

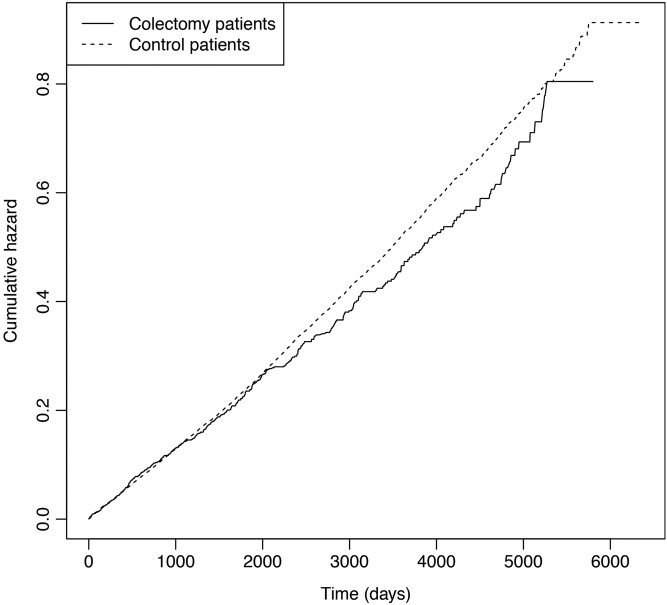

The time-corresponding cumulative hazards of the first occurring composite CVD end point, shown in figure 1, suggest that the risk of CVD was lower in the colectomy group than in the combined control group. However, the reduction in risk was insignificant, with an HR of 0.94 with 95% confidence limits of 0.85 to 1.04 (p=0.22) (table 2). The HR of obtaining a CVD diagnosis in the subgroups of patients with colectomy with IBD and cancer showed virtually the same results (table 3).

Figure 1.

Cumulative hazards of the first occurring cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diagnosis (CVD) in patients with colectomy (n=1530) and control patients (n=22 950). The HR was 0.94, 95% confidence limits 0.85 to 1.04, of CVD in patients with colectomy compared with the matched control patients.

Table 2.

HRs with 95% CIs of any first occurring CVD diagnosis in colectomy and surgical control patients as well as for surgical subgroups

| Number with diagnosis/total | HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with colectomy | 394/1530 | ||

| Control patients* | 6564/22 950 | 0.94 (0.85 to 1.04) | 0.22 |

| Surgical subgroups | |||

| Orthopaedic surgery | 2148/7650 | 0.97 (0.87 to 1.07) | 0.51 |

| Surgery in the GI tract leaving it intact | 2223/7650 | 0.92 (0.82 to 1.02) | 0.11 |

| Other major surgery not in the GI tract | 2193/7650 | 0.93 (0.84 to 1.04) | 0.20 |

*Age and sex matched, but otherwise randomly selected control patients; five for each surgical comparison group of orthopaedic surgery, surgery in the GI tract, and other major surgery not in the GI tract.

Results are adjusted for age and sex.

CVD, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular; GI, gastrointestinal.

Table 3.

HRs, with 95% CIs of a CVD diagnosis by groups of patients with colectomy with either co-occurring IBD or cancer compared with the control patients

| Number with diagnosis/total | HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-occurrence of IBD | |||

| Patients with colectomy | 191/791 | ||

| Control patients* | 3198/11 865 | 0.88 (0.76 to 1.02) | 0.08 |

| Co-occurrence of cancer | |||

| Patients with colectomy | 133/531 | ||

| Control patients | 2385/7965 | 0.93 (0.78 to 1.11) | 0.41 |

*Age and sex matched, but otherwise randomly selected control patients; five for each surgical comparison group of orthopaedic surgery, surgery in the GI tract, and other major surgery not in the GI tract.

Results are adjusted for age and sex.

CVD, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular; GI, gastrointestinal; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

The results pertaining to each of the seven CVD domains revealed that colectomy was associated with tendencies of reduced HRs in most domains and with a statistically significant reduction for hypertensive disorders (table 4).

Table 4.

HRs with 95% CIs of a CVD across the seven CVD domains in patients with colectomy compared with control patients

| CVD-ICD-10 subdomains | Number with diagnosis/total | HR (95% CI) | p Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertensive disorders (I10–I13) | |||

| Patients with colectomy | 187/1530 | ||

| Control patients† | 3474/22 950 | 0.85 (0.73 to 0.98) | 0.03 |

| Acute ischaemic heart diseases (I20, I21, I24, I46) | |||

| Patients with colectomy | 100/1530 | ||

| Control patients | 1751/22 950 | 0.91 (0.75 to 1.12) | 0.38 |

| Chronic ischaemic heart disease (I23, I25, I51) | |||

| Patients with colectomy | 63/1530 | ||

| Control patients | 1224/22 950 | 0.83 (0.64 to 1.07) | 0.15 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias (I44–I49) | |||

| Patients with colectomy | 105/1530 | ||

| Control patients | 1854/22 950 | 0.92 (0.75 to 1.11) | 0.38 |

| Heart failure (I50) | |||

| Patients with colectomy | 57/1530 | ||

| Control patients | 841/22 950 | 1.10 (0.84 to 1.44) | 0.48 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases (I61–I69) | |||

| Patients with colectomy | 85/1530 | ||

| Control patients | 1422/22 950 | 0.96 (0.77 to 1.20) | 0.72 |

| Other arterial diseases (I35, I70–I74) | |||

| Patients with colectomy | 65/1530 | ||

| Control patients | 1227/22 950 | 0.85 (0.67 to 1.10) | 0.21 |

*Tests for whether the HRs are different from 1.00.

†The matched control patient group includes orthopaedic surgery, surgery in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and other major surgery not in the GI tract (see web extra material for NOMESCO diagnoses included).

Results are adjusted for age and sex.

CVD, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular; GI, gastrointestinal; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition.

Discussion

This study investigated the long-term risk of CVD following total colectomy across a panel of diagnoses, which are presumed to be based mainly on atherosclerotic diseases. The postsurgical mortality rate after colectomy was high. By limiting the risk period to 1000 days following surgery and onwards, the all-cause mortality was stable in the colectomy and the control groups, although still with a steadily higher mortality in the colectomy group. Compared with the control group, the patients with colectomy surviving and remaining free of CVDs through 1000 days following surgery had a slightly and insignificantly reduced risk of CVD when analysed as a composite end point, irrespective of co-occurring IBD or cancer and which of the three surgical control groups were used. The same pattern was seen across the CVD domains except for the hypertensive disorders, of which the risk was significantly reduced.

Given the results reported from previous studies of the possible involvement of the intestinal microbiota in atherosclerosis,6 8–10 18 we expected a considerably reduced risk of CVD in patients who had their presumed overall harmful intestinal microbiota reduced by colectomy. However, as discussed in the following paragraphs, various limitations of the study may have masked such effects.

One possibility is an inaccurate classification of CVDs. However, since the composite CVD end point includes most CVD domains, misclassification is not suspected to be a problem in estimating the risk of any CVD, whereas a comparison of risks across a specific CVD diagnosis may be more problematic. It was reassuring that the same results were obtained in the more distinct groups with acute CVDs. Thus, we do not suspect that systematic or random misclassification has influenced the results. On the other hand, depending on the severity of the underlying disease, there may be differences in the number of hospital contacts and thus in the possibility of obtaining a diagnosis of chronic CVD. To take care of such possible bias, different types of surgery were used to form the control groups in which similar opportunities for diagnosis of chronic CVD may exist.

In addition, bias through confounding by indication—meaning that having surgery performed depends on disease severity and presence of comorbidities before surgery—should also have been minimised through the selection of control patients undergoing different surgical procedures. In theory, it would be ideal to compare the patients with colectomy with a group of patients with the same underlying diseases and with the same a priori risk of CVD, but not undergoing colectomy. However, identifying such a control group in the register is not feasible; colectomy is performed on indications based on the type and severity of the underlying diseases, and comparable patients who have not had colectomy, but who have the same type and severity of diseases combined with the same a priori CVD risk, are unlikely to exist in this population.

Patients with colectomy and control patients with a known history of any CVD were censored from the analyses to reduce the possibly differently increased risk of recurrent CVDs. Although of interest, the study population was not suitable for assessment of the effect of colectomy on risk of recurrence of CVDs. A bias may arise due to the lack of data on prior CVDs for patients who had their surgery in the beginning of the study period, but it is assumed that this problem influences the colectomy and the control groups similarly.

By restricting our study group to patients who had colectomy at the age of 45 years and above, we have excluded a younger group of patients who were unlikely to experience a CVD event in the available observation time unless they were particularly predisposed. Following the same entry and follow-up criteria, there were 978 patients in the age range 30–44 years who had colectomy. However, only 84 (8.5%) of them and 1424 (9.7%) of the 14 670 matched control patients experienced a CVD event. With these numbers and distribution of events, we find it unlikely that they can change the conclusion, and, moreover, the numbers do not allow the corroborating stratified analyses. It would be interesting to continue a follow-up of this group through the years where the CVD risk increased to the level of the current group.

The patients undergoing total colectomy usually suffer from severe gastrointestinal diseases, the majority from IBD and cancer. IBD has been associated with elevated risk of CVD, but primarily when the disease flares arise.17 23–27 Lifestyle differences before and after surgery, such as smoking, may also influence the CVD risk. Since smoking may relieve the symptoms in patients with IBD, those who have had colectomy may have been smoking and hence have a greater CVD risk than other patients.28 Moreover, the finding of a continuously increased total mortality in the colectomy group compared to the control group may indicate that they are at increased risk of health problems that could have masked the diagnosis of CVDs. These biases may hide a reduction in CVD risk after colectomy from a level higher than in the control group. On the other hand, the finding of virtually similar effects of colectomy for IBD and for cancer suggests that these biases are limited.

In this regard, patients who had colectomy because of familial adenomatous polyposis would be of particular interest to investigate because of the likely absence of a condition influencing the CVD risk. However, the national register includes far too few of such patients for reliable analyses (10 of the colectomy patients included in the analyses and 21 of the 30–44-year-old patients with colectomy).

The effect of colectomy on CVD risk may have been minimised for various other reasons. Thus, the patient groups may be a mixture of patients with intestinal microbiota that are either increasing or decreasing the CVD risk in such a way that the effect of colectomy in the entire group becomes a net result of interference with oppositely acting microbiota. The risk may also be modified by the microbiota associated with the diseases leading to colectomy and by the alterations in the microbiota in the remaining intestine following colectomy. Furthermore, the study groups may encompass individuals at low risk of CVD that is difficult to reduce further, possibly due to dietary modifications before and after surgery.29–31 Effects of colectomy may also depend on various characteristics of the individuals, such as gender, age, the time frame beyond the present observation period, comorbidities such as diabetes and the CVD history. These aspects may be addressed in future studies, which, however, will require additional information and an even greater study population.

The significantly reduced HR of hypertensive disorders in the patients with colectomy compared to the other surgical groups may be explained by the salt and water depletion, which is a well-known consequence for patients who do not have the colon available for reabsorption of salt and water.32 Since hypertension is a well-established risk factor for most of the other CVDs, it is plausible that the overall, though insignificant, tendency to a lower CVD risk after colectomy may be due to an effect on blood pressure.

Conclusion

While keeping the reservations in mind, we conclude that removal of the major reservoir of the gut microbiota by colectomy did not reduce the risk of CVDs in this population, except for the reduced risk of hypertensive disorders. Whether other ways of modifying the gut microbiota may have a beneficial influence on CVD remain to be investigated.

Footnotes

Contributors: TIAS conceived the study, and TAA, ABJ, SB and TIAS planned the study design and analyses. ABJ performed all analyses. TAA drafted the manuscript and finalised it together with ABJ and TIAS. All authors provided input to the interpretation of the results and commented on the manuscript.

Funding: This study was carried out as a part of the activities in the EU FP-7 TORNADO project, where funding covered TAAs research activities. Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF14CC0001) and the ESICT project grant from the Danish Research Council for Strategic Research supported the research activities of ABJ and SB. In addition, ABJ has been covered by BioMedBridges (funded by the European Commission within Research Infrastructures of the FP7 Capacities Specific Programme, grant agreement number 284209).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data were extracted from the entire Danish National Patient Register. Statistical analyses have been performed with use of R 3.2.0 statistical software and the statistical codes can be made available from the corresponding author on request.

References

- 1.Cani PD. Gut microbiota and obesity: lessons from the microbiome. Brief Funct Genomics 2013;12:381–7. 10.1093/bfgp/elt014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Kinross J et al. . Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science 2012;336:1262–7. 10.1126/science.1223813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tremaroli V, Backhed F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature 2012;489:242–9. 10.1038/nature11552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielsen HB, Almeida M, Juncker AS et al. . Identification and assembly of genomes and genetic elements in complex metagenomic samples without using reference genomes. Nat Biotechnol 2014;32:822–8. 10.1038/nbt.2939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ettinger R, MacDonald K, Reid G et al. . The influence of the human microbiome and probiotics on cardiovascular health. Gut Microbes 2014;5:719–28. 10.4161/19490976.2014.983775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffin JL, Wang X, Stanley E. Does our gut microbiome predict cardiovascular risk? A review of the evidence from metabolomics. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2015;8:187–91. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.000219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen TH, Gøbel RJ, Hansen T et al. . The gut microbiome in cardio-metabolic health. Genome Med 2015;7:33 10.1186/s13073-015-0157-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlsson FH, Fåk F, Nookaew I et al. . Symptomatic atherosclerosis is associated with an altered gut metagenome. Nat Commun 2012;3:1245 10.1038/ncomms2266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang WH, Wang Z, Levison BS et al. . Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1575–84. 10.1056/NEJMoa1109400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ et al. . Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 2011;472:57–63. 10.1038/nature09922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cani PD, Osto M, Geurts L et al. . Involvement of gut microbiota in the development of low-grade inflammation and type 2 diabetes associated with obesity. Gut Microbes 2012;3:279–88. 10.4161/gmic.19625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox LM, Blaser MJ. Pathways in microbe-induced obesity. Cell Metab 2013;17:883–94. 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreno-Indias I, Cardona F, Tinahones FJ et al. . Impact of the gut microbiota on the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Microbiol 2014;5:190 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmadi-Abhari S, Luben RN, Wareham NJ et al. . Seventeen year risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality associated with C-reactive protein, fibrinogen and leukocyte count in men and women: the EPIC-Norfolk study. Eur J Epidemiol 2013;28:541–50. 10.1007/s10654-013-9819-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carvalho BM, Saad MJ. Influence of gut microbiota on subclinical inflammation and insulin resistance. Mediators Inflamm 2013;2013:986734 10.1155/2013/986734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Theocharidou E, Gossios TD, Karagiannis A. Are patients with inflammatory bowel diseases at increased risk for cardiovascular disease? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:2134–5. 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Theocharidou E, Gossios TD, Giouleme O et al. . Carotid intima-media thickness in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Angiology 2014;65:284–93. 10.1177/0003319713477471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown JM, Hazen SL. The gut microbial endocrine organ: bacterially derived signals driving cardiometabolic diseases. Annu Rev Med 2015;66:343–59. 10.1146/annurev-med-060513-093205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendelsohn AR, Larrick JW. Dietary modification of the microbiome affects risk for cardiovascular disease. Rejuvenation Res 2013;16:241–4. 10.1089/rej.2013.1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanage WP. Microbiology: microbiome science needs a healthy dose of scepticism. Nature 2014;512:247–8. 10.1038/512247a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Orginasation. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. WHO, 2011, 2010 Edition, 10th Revision. http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/ICD10Volume2_en_2010.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nordic Medico Statistical Committee (NOMESCO). NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures.[2009 Vers 1.16]. http://nowbase.org/~/media/Projekt%20sites/Nowbase/Publikationer/NCSP/NCSP%201_16.ashx

- 23.Kristensen SL, Ahlehoff O, Lindhardsen J et al. . Disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease is associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular death—a Danish nationwide cohort study. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e56944 10.1371/journal.pone.0056944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rungoe C, Basit S, Ranthe MF et al. . Risk of ischaemic heart disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide Danish cohort study. Gut 2013;62:689–94. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rungoe C, Nyboe Andersen N, Jess T. Inflammatory bowel disease and risk of coronary heart disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2015;25:699–704. 10.1016/j.tcm.2015.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersen NN, Jess T. Risk of cardiovascular disease in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2014;5:359–65. 10.4291/wjgp.v5.i3.359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh S, Singh H, Loftus EV Jr et al. . Risk of cerebrovascular accidents and ischemic heart disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:382–93. 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parkes GC, Whelan K, Lindsay JO. Smoking in inflammatory bowel disease: impact on disease course and insights into the aetiology of its effect. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:717–25. 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graf D, Di CR, Fak F et al. . Contribution of diet to the composition of the human gut microbiota. Microb Ecol Health Dis 2015;26:26164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong JM. Gut microbiota and cardiometabolic outcomes: influence of dietary patterns and their associated components. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100(Suppl 1):369S–77S. 10.3945/ajcn.113.071639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carmody RN, Gerber GK, Luevano JM Jr et al. . Diet dominates host genotype in shaping the murine gut microbiota. Cell Host Microbe 2015;17:72–84. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carmichael D, Few J, Peart S et al. . Sodium and water depletion in ileostomy patients. Lancet 1986;2:625–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)92444-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]