Abstract

Background

With significant developments in the management of metastatic breast cancer, the trajectory of progressive breast cancer is becoming increasingly complex with little understanding of the illness course experienced by women, or their ongoing problems and needs.

Aim

This study set out to systematically explore the illness trajectory of metastatic breast cancer using models from chronic illness as a framework.

Design

Longitudinal mixed methods studies detailing each woman's illness trajectory were developed by triangulating of narrative interviews, medical and nursing documentation and an assessment of functional ability using the Karnofsky Scale. The Corbin and Strauss Chronic Illness Trajectory Framework was used as a theoretical framework for the study.

Participants

Ten women aged between 40 and 78 years, with metastatic breast cancer.

Results

Women’s illness trajectories from diagnosis of metastatic disease ranged from 13 months to 5 years and 9 months. Eight of the 10 women died during the study. Chronic illness trajectory phases identified by Corbin and Strauss (pretrajectory, trajectory onset, living with progressive disease, downward phase and dying phase) were experienced by women with metastatic breast cancer. Three typical trajectories of different duration and intensity were identified. Women's lives were dominated by the physical burden of disease and treatment with little evidence of symptom control or support.

Conclusions

This is the first study to systematically explore the experience of women over time to define the metastatic breast cancer illness trajectory and provides evidence that current care provision is inadequate. Alternative models of care which address women's increasingly complex problems are needed.

Keywords: Supportive care

Introduction

Breast cancer has been the focus of intense study by the scientific community over many decades with initiatives targeted at better management or fair access to new treatments for early stage disease.1 It is therefore surprising that so little attention has been given to the issues faced by women who develop metastatic disease other than in the context of end-of-life care.

It is estimated that in the UK, around 36 000 women are living with progressive disease, with 12 000 being in the last year of life.2 Developments in treatments may be extending survival and improving the management of the disease, leading to the suggestion that breast cancer may be becoming a chronic illness. However as yet, little information exists as to the course of metastatic disease, or whether current models of palliative care services organised around providing intensive support at the end of life are meeting the needs of women living with progressive disease.

Defining the illness trajectory of metastatic breast cancer

The concept of ‘illness trajectory’ has been described extensively in relation to chronic illness and to the process of dying.3 4 It refers to the events over the course of illness which are shaped by the individual's response to illness, interactions with those around them and interventions. Glaser and Strauss3 refer to the events that unfold for an individual who is dying as having two elements—time and shape, and chart the relationship between expectations of when death may occur by professionals, family members and the individual. The concept of trajectory introduced by Strauss et al(ref. 5, p.66) encompasses not only the ‘physiological unfolding of a patient's disease but the total organisation of work done over the course of illness and the impact on those involved with that work and its organization’ and despite the passage of time is still considered relevant today.6 There has been considerable interest in charting the course of different dying trajectories as a means of tailoring palliative care services prior to death,7–10 most recently exploring the experience of patients living through the trajectories of specific cancers, such as glioma.11 Strauss et al5 described a Chronic Illness Trajectory Framework where the pattern of illness is characterised by a cycle of ‘decline-reprieve-decline-reprieve-decline to death’, which renders expectations uncertain and arrangements and plans unpredictable.

This paper reports the findings of a study that set out to systematically explore the illness trajectory of progressive breast cancer and to examine women's experiences while living with the disease.

Methods

Two hundred and thirty-five women were recruited to participate in a national questionnaire survey of health-related quality-of-life and experience of care. The results of the survey are reported elsewhere.12 This paper reports the detailed data from the cases of 10 women selected from the 235 who consented to participate in a longitudinal study of their experiences. Women who took part in the survey were asked to give their contact details if they were interested in taking part in interviews about their experience. A longitudinal mixed-methods approach was adopted. Using a primarily qualitative approach, a number of data sources were combined to systematically chart the illness trajectory of breast cancer from the point of diagnosis of progressive disease until death. Ten women were selected to represent different experiences of progressive breast cancer, such as age and site of metastatic spread, as well as those with indolent and aggressive disease, and where there were also complete medical and nursing records that could be accessed for the research. The characteristics of the 10 women chosen are described in table 1.

Table 1.

Disease characteristics of the 10 women

| Disease characteristics | n (Mean) |

|---|---|

| Age range | 40–78 years (54) |

| Disease-free survival | 1–10 year (3) |

| Number of metastatic sites | 1 site: 2 women |

| 2 sites: 2 women | |

| 3 sites: 6 women | |

| Time living with metastatic disease* | 13 months to 7 years 3 months (4 years) |

*One woman diagnosed with metastatic disease at first presentation.

Women were interviewed three times over one calendar year using a qualitative narrative approach.13 All interviews were conducted in the participants’ homes by one interviewer (ER). Each lasted, on average, 60 min. Each woman was given the opportunity to withdraw from the study before each interview, and support materials and contacts were made available to all participants. Data from women's narrative interviews and documentation (including medical notes, oncologist annotations of appointments, nursing notes, correspondence between healthcare professionals, investigation results) were triangulated to map in detail the illness trajectory of each woman's metastatic breast cancer. Over one calendar year, eight women were interviewed three times; two women were interviewed twice, but died before the final interview.

A biographic narrative interview approach13 was adopted to explore in detail women's experience of living with progressive breast cancer. Narrative inquiry differs from conventional interviewing in that variation in responses is as important as consistency, and diversity in the narrative is sought through a less formal interview schedule and more of an interactionalist approach.14 At the first interview, the opening question was ‘tell me about yourself’. Subsequent interviews began with an open question, ‘tell me what has happened since we last spoke’. The participant, rather than the interviewer determines the narrative form.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed in their entirety. A framework was developed using Lieblich et al's13 holistic-form and holistic-content analysis approach. Metastories were developed for each woman from the three interviews to build a chronologically ordered story. Data collected from clinical documentation were added to the metastories. Diagrammatic representations of the illness trajectories were then developed. Using data from medical records and women's narrative accounts, a retrospective estimate of women's functional ability was made from first diagnosis of metastatic disease until the end of data collection, or death, to develop a graphic representation of the 10 trajectories using the Karnofsky Scale15 (table 2). These assessments were placed alongside the women's metastories. Key trajectory events from the metastories were then superimposed onto the trajectory to reflect women's illness experience and the health system's response to it.

Table 2.

Karnofsky Performance Scale15

| Value | Level of functional capacity |

|---|---|

| 10 | Normal, no complaints, no evidence of disease |

| 9 | Able to carry on normal activity, minor signs or symptoms of disease |

| 8 | Normal activity with effort, some signs or symptoms of disease |

| 7 | Cares for self, unable to carry on normal activity or to do active work |

| 6 | Requires occasional assistance, but is able to care for most needs |

| 5 | Requires occasional assistance and frequent medical care |

| 4 | Disabled, requires special care and assistance |

| 3 | Severely disabled, hospitalisation is indicated although death is not imminent |

| 2 | Hospitalisation is necessary, very sick, active supportive treatment necessary |

| 1 | Moribund, fatal processes progressing rapidly |

| 0 | Dead |

Existing trajectories of dying3 4 were reviewed to examine the ‘fit’ of these to the trajectories derived from the metastories and were found not to reflect the data. Instead, Corbin and Strauss’ Chronic Illness Trajectory Model16 was felt to better explain the experiences of women in this study and was therefore used as a framework to describe the illness trajectory of metastatic breast cancer (table 3).

Table 3.

Definitions of the Corbin and Strauss Chronic Illness Trajectory Model phasing16

| Phase | Goal of definition | Goal of management |

|---|---|---|

| Pretrajectory | Genetic factors or lifestyle behaviours that place an individual or community at risk for the development of a chronic condition | Prevent onset of chronic illness |

| Trajectory onset | Appearance of noticeable symptoms, includes periods of diagnostic workup and announcement by biographical limbo as person begins to discover and cope with implications of diagnosis | Form appropriate trajectory projection and scheme |

| Stable | Illness course and symptoms are under control. Biography and everyday life activities are being managed within limitations of illness. Illness management centres in the home | Maintain stability of illness, biography and everyday activities |

| Unstable | Periods of inability to keep symptoms under control or reactivation of illness. Biographical disruption and difficulty in carrying out everyday life activities. Adjustments being made in regime with care usually taking place at home | Return to stability |

| Acute | Severe and unrelieved symptoms or development of illness complications necessitating hospitalisation or bed rest to bring course under control. Biography and everyday life activities temporarily placed on hold or drastically cut back | Bring illness under control and resume normal biography and everyday life |

| Crisis | Critical or life-threatening situation requiring emergency treatment or care. Biography and everyday life activities suspended until crisis passes | Removal of threat |

| Comeback | A gradual return to an acceptable way of life within the limits imposed by disability or illness. Involves physical healing, limitations stretched through rehabilitative procedures, psychosocial coming to terms, and biographical re-engagement and adjustment in everyday life | Set in motion and keep going the trajectory projection and scheme |

| Downward | Illness course characterised by rapid or gradual physical decline accompanied by increasing disability or difficulty in controlling symptoms. Requires biographical readjustment and alterations in everyday life with each major downward step | To adapt to increasing disability with each major downward turn |

| Dying | Final days before death. Characterised by gradual or rapid shutting down of bodily processes, biographical disengagement and relinquishment of everyday life and activities | To bring closure, let go and die peacefully |

Findings

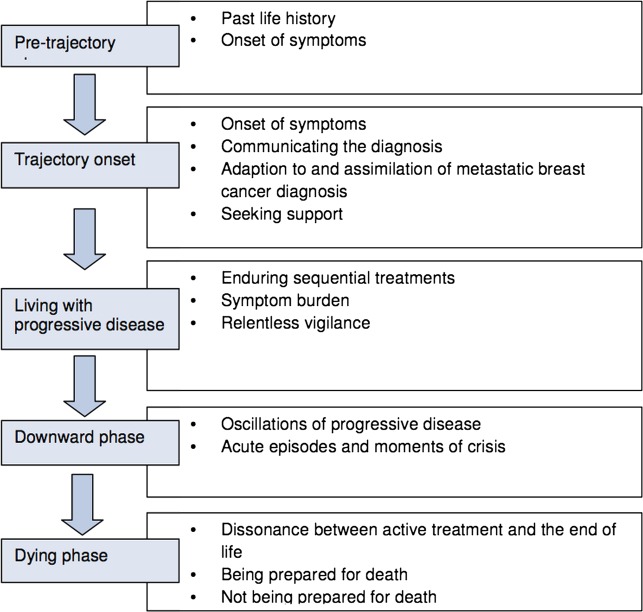

As in Corbin and Strauss’ model, five trajectory phases were identified; the pretrajectory phase, trajectory onset, living with progressive disease, downward phase and dying phase (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Metastatic breast cancer illness trajectory phases.

Phase 1: The pretrajectory phase of metastatic breast cancer

Women's narratives began by describing events before metastatic disease was diagnosed. This included life before their diagnosis of primary disease, and life after completing treatment for early stage disease. Reflecting back, women tried to identify the cause of their disease progressing, a common theme was to attribute this to previous life stress or lifestyle; women felt personal responsibility for their disease progression.

‘I just kind of thought I had to be superwoman...and that was a really stupid thing to do and I had three different jobs and I was doing between 50–60 hours a week…I just couldn't see the bigger picture and I do think that contributed to, to sort of the speed up of my condition I am sure.’ Dawn

Women identified other life events which they feared as possible causes of progressive disease, such as marital breakdown.

Phase 2: The trajectory onset—diagnosis and adjustment to progressive disease

Most of the women experienced an insidious onset of symptoms over time. From presenting with symptoms to getting the diagnosis could be long and complex.

Having spent really hundreds of pounds at the chiropractor, various other things trying to get my back sorted out…the pain got worse…it never really sort of seemed to resolve and a very long story, after seeing her [chiropractor], she said I think you should go back to the doctor so I went to the doctor and they sent me for an x-ray. Jill

This was of great concern to some of the women, because of the worry that in the ensuing time their disease would be progressing and reduce their overall survival. Women appeared unsure how to re-enter the healthcare system, and often took a convoluted path before getting an appointment. Once within, there appeared no structured pathway to ensure they received appropriate care and support.

How the diagnosis and future was explained was key to how women coped. When a level of hope was given that treatment was aimed to improve symptoms or extend survival time, the women felt more confident about the future. However, if the limitations of treatment were emphasised, or a poor prognosis given, it had a significant impact on the women's ability to cope and adjust to the diagnosis. The process of adaptation and assimilation of the news of progressive cancer for some took time and was challenged by the physical manifestations of disease and the side effects of treatment.

By contrast with the diagnosis of primary breast cancer, when metastatic disease was diagnosed, few women appeared to have access to formal support services describing their main support as family and friends. One woman felt she had been ‘cast adrift’ with no healthcare professional to support her. Following her diagnosis of brain metastases, Angela felt the need for support but did not know how to access this.

I don't know what I expected or what sort of care I expected; not knowing what there is to be offered you know? Nobody's ever offered anything or said “oh well, we'll visit you” or anything like that…even if it was a little phone call to see how you are because you feel like you're…you've been told, you've been diagnosed, you're sent home and that's it. What do you do about it? That's how I felt. I was just thinking well what do I do about it? Angela

Few women had access to formal support, and the mobilisation of support services appeared to be associated with a physical need only.

Phase 3: Living with progressive disease

Uncertainty pervaded every element of women's lives during this phase of illness. The continual oscillations between illness, treatment and recovery that women experienced undermined their ability to adjust. Those with more aggressive disease appeared to have little respite from the cycle of disease progression and treatment. They struggled to keep pace with changing events which eroded their sense of self and ability to adjust and adapt to the rapidity of events, at the same time as coping with the present and a foreshortened future.

For example, Jill's illness trajectory highlighted a life with metastatic breast cancer which was dominated by sequential treatments. Over a 3-year period, she endured nine different episodes of treatment (bisphosphonates, radiotherapy and chemotherapy). Jill went through cycles of feeling and looking well and living her life to the full, followed by disease progression and illness.

Most women appeared to tolerate uncontrolled pain, and self-medicated, supporting the findings of our survey which found over one-third of women (34%) reporting high levels of pain and other uncontrolled symptoms.12 There appeared to be little ongoing palliation of symptoms. Angela was prescribed analgesia, but tolerated uncontrolled pain for 4 years.

It is just, it is just like a, a gnawing pain and it is, sometimes it gets you down because you think God just go away for the day and sometimes I think if only I could have one day where I think oh I feel really good today and it never happens, that, that is what I think gets to you because you just feel so bad all the time. Angela

A few of the women had involvement with palliative care services, but only one (Mary) maintained this relationship over time.

While treatment allowed some respite from the symptoms of progressive disease and potentially increased their survival time, living with a progressive disease appeared exhausting in its relentlessness.

Once I came off the chemo there's this sense of kind of waiting, and there's this sense of paranoia that I'm kind of looking every day and feeling and prodding and pushing and thinking “what can I feel?” “What can I see?” “Am I OK or not?” “Am I kidding myself?” I know that's not the way to live, you should just kind of embrace every day and get on with it. Dawn

All the women had times when their disease was stable. During this time, anticipating progressive disease meant the women lived with relentless vigilance over their bodies.

Phase 4: downward phase

The downward phase of illness was characterised by episodes of illness and crisis of increasing frequency. Acute episodes were often a result of chemotherapy side effects, physical deterioration, uncontrolled symptoms, such as breathlessness and cerebral symptoms. Five of the women attended an accident and emergency department during this phase.

Crisis events marked the final downward phase for four of the women. All were admitted to hospital via an accident and emergency department; two for uncontrolled pain and two for neutropenic sepsis associated with chemotherapy.

Phase 5: dying phase

Eight of the women died during the study. The events leading to Joy's death are unknown. Of the remaining seven, one died peacefully at home, three died in a hospice and three died in hospital. All those admitted to either the hospice or hospital died within days of admission, other than Paula who died within 2 weeks.

Of the four who had unplanned admissions leading to their death, two had neutropenic sepsis associated with chemotherapy. From the illness trajectories of these women it appears that they were actively treated up until and including the dying phase of their lives. There was a decision to stop active treatment (chemotherapy) for three women.

The constant quest for the next treatment and to prolong their lives meant few had support services in place to help them until the end stage of their lives. Some knew there were support services but associated them (palliative care and the hospice movement) with the end of life and appeared reluctant to access them. Few had an established relationship with a palliative care service before the last year of life, and for some only days or weeks before death. There appeared to be little awareness of where to seek information about end-of-life care.

You know, no one has ever offered anything, or said oh well we'll visit you or anything like that. The other concern I have got is when it comes right near the end when I am really poorly what do I do? Do I just stay here or do I go into hospital? Do you have to book something? Or that sort of thing… [pause] that I think you really don't know. Angela

Angela asked her general practitioner (GP) to refer her to a community palliative care team 2 years before she died, and he told her she was not ready for that yet, even though she had endured uncontrolled pain and other symptoms throughout her illness trajectory.

Among the women who died, there was a rapid decline towards the end of their lives; the end of their lives appeared to illustrate disintegrated dying,4 where the events were chaotic and the end of anticancer treatment overlapped with the end of life. Consequently, there appeared to be little preparation for death.

At Mary's last hospital appointment, when a CT scan showed her disease had progressed despite the treatment, she decided not to have any further treatment.

The funny thing was when I walked out of the room from seeing the specialist I felt as if the weight had been lifted off my mind, which sounds peculiar but I think you feel right, well you've done everything you possibly can, you can't do anymore, you know, go out there and live your life every day. And that's what I plan to do. Mary

While it cannot be claimed that the role of supportive palliative care services and GP had an influence on Mary dying at home, this illness trajectory was the exception, and the support services Mary received, as well as good social support, were almost certainly influential in this.

Typical illness trajectories

While the issues faced by all 10 women were similar, the course of illness was not the same for all of them. Three typical but different illness trajectories were identified.

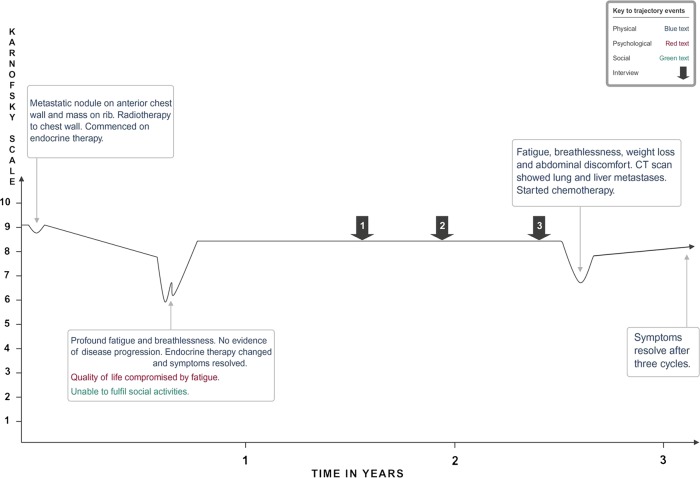

Illness trajectory 1 ‘ticking over nicely’: is illustrated by Joan (figure 2). It was typically long, spanning years and characterised by indolent disease, often with bone metastases, but no other sites of disease spread for a considerable time. Physical functioning was high. Joan was asymptomatic for the majority of the illness trajectory, and for the most part maintained her physical functioning at a high level. She experienced two different endocrine treatments, and one chemotherapy regimen.

Figure 2.

Illness trajectory ‘ticking over nicely’.

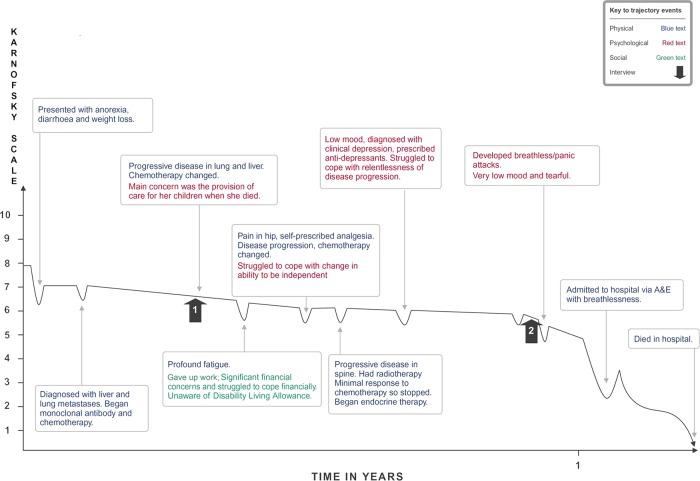

Illness trajectory 2 ‘is there no end to it’: is illustrated by Paula (figure 3) and was characterised by a short duration, with a gradual deterioration in physical functioning punctuated by episodes of disease progression, uncontrolled symptoms, sequential treatment and its side effects, with little respite. Paula had aggressive, rapidly progressing disease.

Figure 3.

Illness trajectory ‘is there no end to it?’.

Over the 13-month period Paula experienced three episodes of disease progression, three different chemotherapy regimens, one endocrine therapy and one fraction of radiotherapy for bone pain. She was physically compromised for the majority of time, experiencing pain and fatigue throughout the illness trajectory which she managed herself. She accessed no palliative care services until an acute hospital admission for breathlessness 1 month before she died.

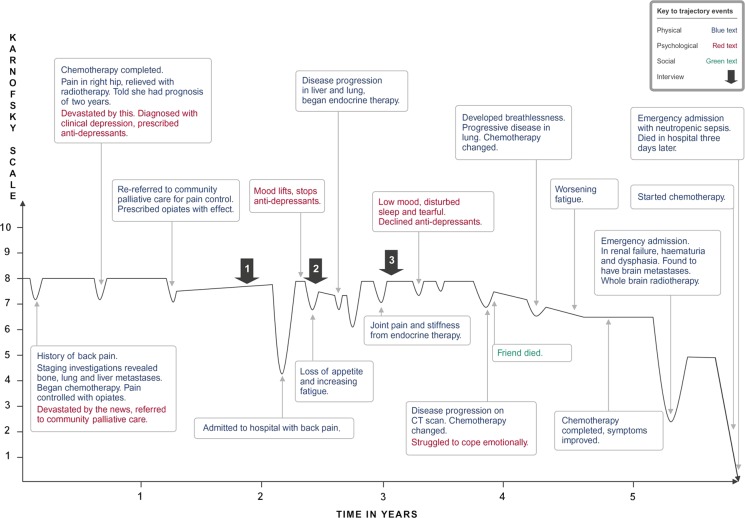

Illness trajectory 3 ‘it's a rollercoaster’: is illustrated by Shelley (figure 4). This appeared to be the most typical illness trajectory, where the duration was longer (2–5 years or more). Physical functioning could decline but then recover, and at times increase to a level higher than before an event which caused the decline. Shelley experienced the oscillations of disease progression, treatment and the restoration of a level of well-being, as well as acute episodes and crises.

Figure 4.

Illness trajectory ‘it's a rollercoaster’.

Discussion

This study suggests that for many women with metastatic breast cancer, cycles of decline and reprieve are the norm over an extending lifespan. Both the number of decline-reprieve cycles, and the time interval between these, can become extended because of the availability of a large number of new treatment options. The consequence of this is that women's lives are dominated by treatment and they endure chronic pain and symptoms that they largely manage for themselves. Women find themselves in a complex relationship with their oncologist where cycles of treatment are offered, accepted and endured as the only option for prolonging life at whatever cost, with little apparent planning for moments of decline resulting in admissions to hospital and the final months of life are characterised by disintegrated dying. Trajectories 2 and 3 could both be characterised as disintegrated dying trajectories4 though these were experienced over an extended period of time by women. Trajectory 3 could be considered more of an episode within a longer, yet to be concluded trajectory.17This trajectory would more closely fit with Strauss et al's5 characterisation of the chronic illness trajectory of decline-reprieve-decline-reprieve-death.

Women are not in ‘denial’ over the seriousness of their illness, but find themselves with their oncologists, caught in a constant bid for further illness reprieve. Oncologists are hampered by the difficulty in recognising when the final decline has commenced or may occur, or that women may die from the consequences of treatment itself.

The approach taken in this study of combining different sources of data with women's narrative accounts of their illness experience, has proved valuable in identifying the pattern of metastatic breast cancer, and could provide a means of identifying those in most need of support. Its strengths were the range of women's experience, the longitudinal design and the addition of clinical documentation. The findings support our earlier survey that there is little evidence of palliative care involvement with these patients,12 and indicates that palliative care is needed much earlier than presently provided.

The study challenges the configuration of palliative care services that focus on the end of life, when an increasing number of those with metastatic cancer are considered survivors who may live for years with progressive disease. By turning to the management of chronic illness, models of care incorporating approaches to supported self-management policy makers and clinicians could better address the needs of those living over time with progressive disease. This change may have cost benefits for healthcare provision through, for example, more appropriate use of analgesics and anticancer treatment, and a reduction in unnecessary hospital admissions.

Palliative care services have the expertise and experience to improve quality of life in metastatic disease, but the focus is currently on the end of life which is only is a short phase of a much longer illness trajectory, with the final decline becoming increasingly difficult to identify. A more integrated oncology and palliative care approach is needed to support women and oncologists in making difficult decisions over when to stop treatment and to plan for end of life.

Conclusion

This is the first study to systematically study the events that unfold for women with metastatic breast cancer in the context of current treatment. It suggests that significant adjustment needs to be made to current models of care, as these are no longer fit for purpose given the increasingly chronic nature of the disease.

Limitation

The illness trajectory of 10 women with metastatic breast cancer may not be a true representation of all those with metastatic breast cancer throughout the UK.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Peter Simmonds.

Contributors: ER and JC both obtained funding for the study. ER was responsible for data collection and analysis. ER and JC both contributed equally to the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from Breast Cancer Campaign (grant number 2003:622).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Southampton and South West Hampshire Research Ethics Committee. REC No: 04/Q1704/19.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Peter Simmonds

References

- 1.Knox S. Health Economic Decision making in Europe—a new priority for breast cancer advocacy. Breast 2009;18:71–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maher J, McConnell L. New pathways of care for cancer survivors: adding the numbers. Health Psychol 2011;105:S5–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glaser B, Strauss A. Time for dying. New Jersey: Aldine Transaction, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pattison EM. The experience of dying. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall Inc, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strauss AL, Corbin J, Fagerhaugh S, et al. Chronic illness and the quality of life. 2nd Edn., St Louis: Mosby, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Small N, Gott M. The contemporary relevance of Glaser and Strauss. Mortality: promoting the interdisciplinary study of death and dying 2012;17:355–77. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gott M, Barnes S, Payne S, et al. Dying trajectories in heart failure. Palliat Med 2007;21:95–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, et al. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA 2003;289:2387–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Field D, Copp G. Communication and awareness about dying in the 1990's. J Palliat Med 1999;13:459–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Copp G, Field D. Open awareness and dying: the use of denial and acceptance as coping strategies by hospice patients. J Res Nurs 2002;7:118–27. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavers D, Hacking MA, Erridge SE, et al. Social, psychological and existential well-being in patients with glioma and their care givers: a qualitative study. CMAJ 2012;184:E373–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reed E, Simmonds P, Haviland J, et al. (2012) Quality of life and experience of care in women with metastatic breast cancer: a cross sectional survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;43:747–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lleiblich A, Tuval-Mashiach R, Zilber T. Narrative research. Reading, analysis and interpretation. Applied social research series Vol 47. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattingley C, Garro LC. Narrative and the cultural construction of illness and healing. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: MacLeod CM. Evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents. Columbia: Open University Press, 1949:196. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corbin JM. The corbin and strauss illness trajectory model: an update. Sch Inq Nurs Pract 1998;12:3–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiener C, Fagerhaugh S, Suczek B, et al. Social organization of Medical Work. University of Chicago Press, 1985, no 1/1997. [Google Scholar]