Abstract

Cardiac rhabdomyoma is the most common primary cardiac tumour during childhood and is usually associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). These tumours are generally considered benign, and spontaneous regression occurs commonly. However, when the tumours cause significant symptoms, the current standard treatment is surgical resection. Everolimus is an mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 1 inhibitor that has been successfully used to treat subependymal giant cell astrocytomas and renal angiomyolipomas associated with TSC. A few case reports have described the effectiveness of everolimus therapy in treating cardiac rhabdomyomas as well. We report a case of a newborn who had near complete resolution of multiple rhabdomyomas within a month of receiving everolimus therapy for non-cardiac masses. To the best of our knowledge, this is the fastest resolution of cardiac rhabdomyomas associated with everolimus therapy to date. Everolimus may be a promising alternative for high-risk surgical candidates with haemodynamically significant cardiac rhabdomyomas.

Background

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal dominant neurocutaneous syndrome caused by mutation in either the tuberous sclerosis complex 1 (TSC1) or TSC2 tumour-suppressor genes. When either TSC1 (hamartin) or TSC2 (tuberin) is deficient, mTOR complex 1 is upregulated, leading to abnormal cellular growth, proliferation and protein synthesis.1–3 TSC is characterised by formation of hamartomas in multiple organs including the brain, skin, heart, lungs, kidneys and retina.1 2 Cardiac rhabdomyoma is the most common primary cardiac tumour during childhood, representing 45–75% of all tumours,4 5 and is present in approximately 50% of TSC cases.6 Cardiac rhabdomyomas are generally considered benign and most patients are asymptomatic.7 When present, symptoms may include dysrhythmias, intracardiac obstruction to blood flow and congestive heart failure. The natural history in many cases is spontaneous regression.8 9 While the mechanism of regression is not clearly known, increased apoptosis has been reported in some cases.8 10 The current standard treatment of symptomatic cardiac tumours is surgical resection, usually for cases of clinically significant obstruction or heart failure. Everolimus is an mTOR complex 1 inhibitor that has been successfully used against subependymal giant cell astrocytomas (SEGAs) and renal angiomyolipomas.1 Its use for treatment of cardiac rhabdomyomas is currently not standard practice, although its efficacy in treating cardiac rhabdomyomas has been described in rare case reports.6 9 We describe a case of rapid resolution of multiple rhabdomyomas in an infant being treated for non-cardiac masses. The swift clinical course was shown well with echocardiography.

Case presentation

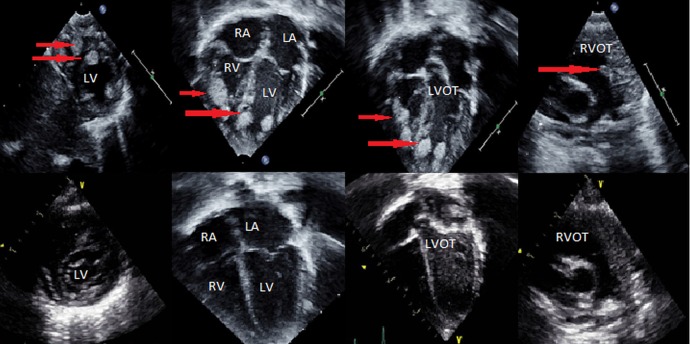

A 2-week-old term neonate was admitted to our hospital, with concerns for apnoeic spells. He was the first child of non-consanguineous healthy parents, and was born by caesarean section for failure to progress. His birth weight was 3.65 kg. Neurological evaluation revealed the diagnosis of infantile spasms and brain MRI showed presence of subependymal nodules. A renal ultrasound was concerning for angiomyolipomas. The patient was diagnosed with TSC. On admission, his heart rate was 140 bpm, blood pressure was 90/70 mm Hg and oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. His cardiovascular examination was normal, with no murmur on examination and no signs of heart failure. His ECG was normal. An echocardiogram obtained as part of TSC evaluation showed multiple rhabdomyomas (figure 1 and videos 1–3). There were eight different rhabdomyomas noted in multiple locations. The sizes of the tumours ranged from 3 to 12 mm (figure 1 with arrows). The patient had one mass in the subpulmonic region and another mass lateral to the pulmonary valve (figure 1 and video 4). Neither caused subpulmonary stenosis, pulmonary stenosis or pulmonary regurgitation. Two rhabdomyomas were noted in the right ventricle, two masses in the left ventricular septal wall and two masses in the left ventricular free wall. There was no significant atrioventricular valve, or semilunar valve stenosis or regurgitation, and there was normal biventricular systolic function. A diagnosis of TSC with multiple rhabdomyomas was made.

Figure 1.

Echocardiographic images of cardiac rhabdomyomas from parasternal short axis, apical four-chamber, apical five-chamber and parasternal short axis showing right ventricular outflow tract. Images on top demonstrating dense echogenic masses before everolimus treatment. The images below demonstrating resolution of rhabdomyomas within a month of initiating everolimus therapy. The arrows indicating the location of the masses (top). (LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract).

Video 1.

Cardiac rhabdomyomas from parasternal short axis on two-dimensional echocardiogram. This video demonstrating dense echogenic masses before everolimus treatment. The arrows indicating the location of the masses.

Video 2.

Cardiac rhabdomyomas from apical four-chamber view. This video demonstrating dense echogenic masses in the right and left ventricular cavity before everolimus treatment. The arrows indicating the location of the masses.

Video 3.

Cardiac rhabdomyomas from apical five-chamber view. This video demonstrating unobstructed flow across left ventricular outflow tract. The arrows indicating the dense echogenic masses in the right and left ventricular cavity before everolimus treatment.

Video 4.

Cardiac rhabdomyoma from parasternal short axis on two-dimensional echocardiogram. This video demonstrating dense echogenic masses in the right ventricular outflow tract before everolimus treatment. The arrow indicating the location of the mass in right ventricular outflow tract.

Investigations

Brain MRI: subependymal nodules

Renal ultrasound: angiomyolipomas

ECG: normal

Echocardiogram: highly echogenic, multiple, well-circumscribed intramural nodules consistent with rhabdomyomas.

Differential diagnosis

Primary cardiac tumour

Fibromas.

Treatment

The patient was started on everolimus to treat SEGA.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was seen in cardiology clinic 1 month later, and continued to have a normal examination. A follow-up echocardiogram showed apparent resolution of all intracardiac masses (figure 1 and videos 5–8), and continued normal systolic function. The patient's ECG was also normal at follow-up.

Video 5.

Parasternal short axis view on two-dimensional echocardiogram, near complete resolution of the dense echogenic masses within a month of initiating everolimus therapy.

Video 6.

Apical four-chamber view on two-dimensional echocardiogram, with near complete resolution of the dense echogenic masses within a month of initiating everolimus therapy.

Video 7.

Apical five-chamber view in colour. This video demonstrating near complete resolution of the dense echogenic masses within a month of initiating everolimus therapy and unobstructed flow across left ventricular outflow tract.

Video 8.

Parasternal short axis in colour. This video demonstrating near complete resolution of the dense echogenic masses within a month of initiating everolimus therapy and unobstructed flow across right ventricular outflow tract.

Discussion

Cardiac rhabdomyomas are usually asymptomatic benign cardiac tumours, known to regress spontaneously. Therefore intervention is indicated only in patients with serious haemodynamic conditions such as ventricular inflow or outflow obstruction, valvular dysfunction or congestive heart failure.8 9 The current standard of care for such symptomatic cardiac tumours is surgical resection. However, deep locations or giant tumour masses compressing and infiltrating the heart frequently cannot undergo complete resection.9 Other factors adding risk to the surgery include small patient size or prematurity. Everolimus is an mTOR complex 1 inhibitor that has been successfully used against SEGAs and angiomyolipomas associated with TSC.1 A few case reports have also reported the effectiveness of everolimus therapy in shrinkage of cardiac rhabdomyomas.6 9 In this case report, we describe the rapid resolution of multifocal cardiac rhabdomyoma following everolimus therapy started for SEGA. Cardiac rhabdomyoma has been reported in the newborn,9 however, to the best of our knowledge, our case had the fastest resolution of cardiac rhabdomyoma reported thus far in the literature. Although cardiac rhabdomyomas are known to regress spontaneously, the rapidity with which the cardiac tumour regressed suggests the role of everolimus therapy as a potential contributor. Similar to our experience, Tibero et al reported an incidental finding of near complete regression of cardiac rhabdomyoma following initiation of everolimus therapy for SEGAs. However, according to their report, it took almost 13 months for near complete resolution compared to ours, which showed significant regression of cardiac rhabdomyoma within a month of initiation of everolimus treatment.6 Demir et al9 also reported their experience of successfully treating symptomatic cardiac rhabdomyoma with everolimus therapy; their patient was not a candidate for surgery due to extensive intramural involvement. In conclusion, everolimus treatment may be a potential option for first-line therapy in patients with haemodynamically significant rhabdomyomas, especially in high-risk surgical candidates. Prospective investigation in a large cohort is warranted to further investigate.

Learning points.

Cardiac rhabdomyoma is the most common primary cardiac tumour during childhood and is usually associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC).

Everolimus is an mTOR complex 1 inhibitor that has been successfully used against subependymal giant cell astrocytomas and angiomyolipomas associated with TSC.

Everolimus may be a promising alternative for high-risk surgical candidates with haemodynamically significant cardiac rhabdomyomas.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Krueger DA, Care MM, Holland K et al. Everolimus for subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1801–11. 10.1056/NEJMoa1001671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang J, Manning BD. The TSC1-TSC2 complex: a molecular switchboard controlling cell growth. Biochem J 2008;412:179–90. 10.1042/BJ20080281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan JA, Zhang H, Roberts PS et al. Pathogenesis of tuberous sclerosis subependymal giant cell astrocytomas: biallelic inactivation of TSC1 or TSC2 leads to mTOR activation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2004;63:1236–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elderkin RA, Radford DJ. Primary cardiac tumors in a pediatric population. J Paediatr Child Health 2002;38:173–7. 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2002.00734.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verhaaren HA, Vanakker O, De Wolf D. Left ventricular outflow obstruction in rhabdomyoma of infancy: meta-analysis of the literature. J Pediatr 2003;143:258–63. 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00250-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tiberio D, Franz DN, Phillips JR. Regression of a cardiac rhabdomyoma in a patient receiving everolimus. Pediatrics 2011;127:e1335–7. 10.1542/peds.2010-2910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotulska K, Larysz-Brysz M, Grajkowska W et al. Cardiac rhabdomyomas in tuberous sclerosis complex show apoptosis regulation and mTOR pathway abnormalities. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2009;12:89–95. 10.2350/06-11-0191.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karnak I, Alehan D, Ekinci S et al. Cardiac rhabdomyoma as an unusual mediastinal mass in a newborn. Pediatr Surg Int 2007;23:811–4. 10.1007/s00383-007-1875-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demir HA, Ekici F, Erdem AY et al. Everolimus: a challenging drug in the treatment of multifocal inoperable cardiac rhabdomyoma. Pediatrics 2012;130:e243–247. 10.1542/peds.2011-3476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu SS, Collins MH, De Chadarevian JP. Study of the regression process in cardiac rhabdomyomas. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2002;5:29–36. 10.1007/s10024-001-0001-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]