Abstract

A middle-aged ex-smoker, with a history of curative surgery for oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma 7 years earlier, presented to the casualty department at Mater Dei Hospital with stridor and a 2-week history of progressively worsening dyspnoea. A thoracic CT scan showed the presence of a posterior mediastinal mass involving the upper half of the stomach and posterior wall of the trachea. Histology of an exophytic ulcerating lesion at 25 cm of the oesophagus was that of squamous cell carcinoma. Bronchoscopy performed to ascertain the cause of the stridor showed the trachea to be 70% occluded. The patient showed symptomatic improvement with radiotherapy and intravenous dexamethasone; however, he passed away a few weeks later due to respiratory failure secondary to tracheal occlusion.

Background

Oesophageal cancer is the sixth leading cause of cancer death worldwide.1 Patients with oesophageal malignancy tend to present late since early symptoms are subtle and non-specific. The commonest presenting symptoms are reported to be progressive solid food dysphagia accompanied by weight loss. In this case, we present a middle aged man, who complained of stridor secondary to an underlying oesophageal malignancy.

Case presentation

A middle-aged ex-smoker was brought to the Casualty department at Mater Dei Hospital with a 2-week history of progressively worsening shortness of breath. Seven years earlier, the patient had undergone a partial oesophagectomy and gastrectomy for squamous cell carcinoma. As a young person, the patient had also undergone bilateral partial pneumonectomies for gun-shot wounds to the chest wall. There was no recent history of dysphagia or weight loss. On examination, a harsh, high-pitched sound was noted, heard mainly during expiration, suggestive of stridor. Oxygen saturations were found to be 97% on room air. The patient showed minimal symptomatic improvement following nebulised salbutamol and ipratropium bromide.

Investigations

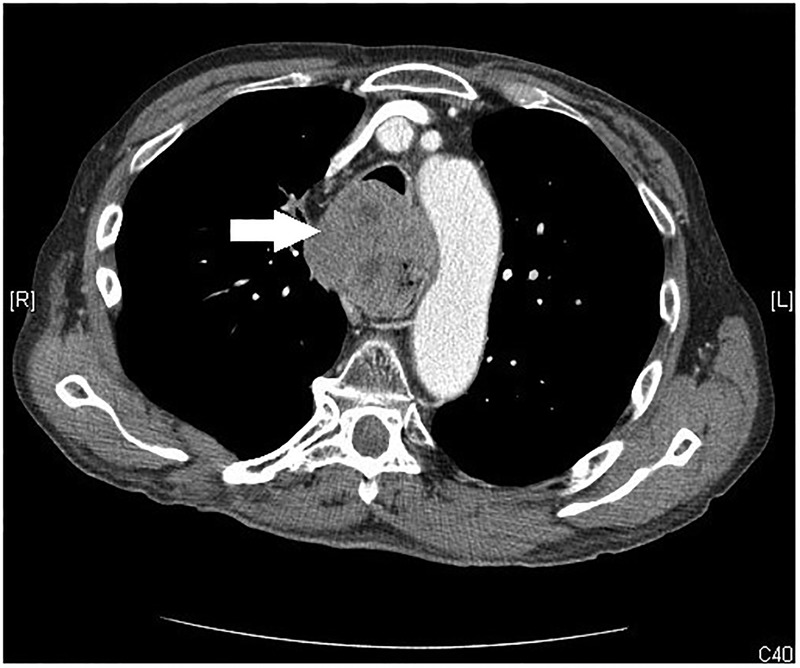

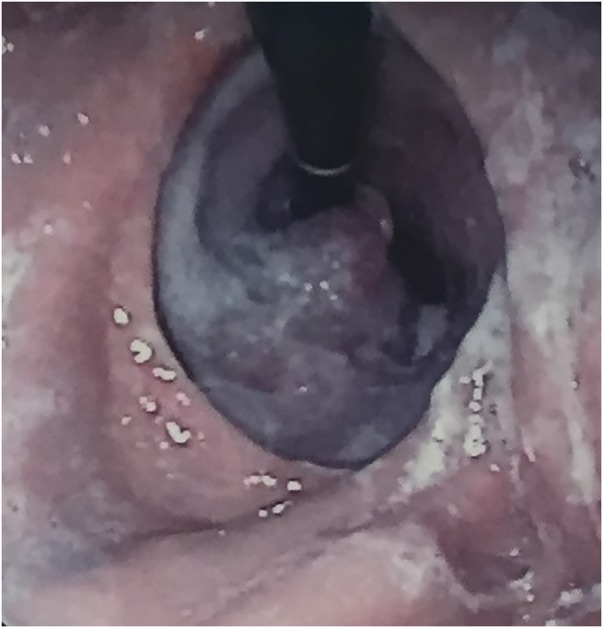

Following a chest X-ray, which showed a widened mediastinum, a CT scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis was performed, which showed the presence of a large, inhomogeneous mediastinal mass measuring about 8 cm in extent and located in the upper chest, extending from a level above the thyroid isthmus down to the level of the tracheal bifurcation with about 9 cm craniocaudal extent. The mass was shown to involve the upper half of the stomach and posterior part of the trachea while being in contact with several structures, including the brachiocephalic artery and anterior borders of the third to sixth thoracic vertebral bodies (figure 1). A bronchoscopy was performed to visualise the extent of tracheal infiltration by the oesophageal mass. The trachea was found to be 30% patent (video 1). An uncomplicated oesophagogastroduodenoscopy was also performed and biopsies of an exophytic ulcerating lesion at 25 cm revealed the presence of an infiltrative poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (figure 2).

Figure 1.

CT scan of the thorax just above the level of the carina, showing a mediastinal mass.

Figure 2.

Exophytic lesion at 25 cm of the oesophagus.

Video 1.

Bronchoscopy showing tracheal infiltration and almost complete obstruction of the lumen.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis in this case includes obstructive lesions of the supraglottis or pharynx, lesions of the thoracic trachea, primary and secondary bronchi, for example, due to inhalation of a foreign body, a tumour pushing either extrinsically or growing intrinsically, infection or oedema, and lesions of the glottis, subglottis and cervical trachea.

Treatment

The patient was reviewed by the oncology team. In view of the presence of an inoperable lesion with extremely poor prognosis, a palliative course of intravenous dexamethasone and external beam radiation therapy was offered to the patient.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient showed initial symptomatic improvement, however, he died a few weeks after initiation of therapy.

Discussion

The commonest symptom of oesophageal malignancy is dysphagia. We have presented this case in order to emphasise the importance of including oesophageal malignancy in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with stridor. Other than direct invasion of the trachea by the tumour, stridor in the presence of an oesophageal malignancy may be due to vocal cord involvement.2 The presence of subaortic lymph nodes or impingement of the trachea at the tracheo-oesophageal groove may lead to recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy and thus vocal cord paralysis. Laryngoscopy plays an important role in assessing vocal cord function. In our case, laryngoscopy was not performed as it was decided to go directly to bronchoscopy during which vocal cord movement was assessed and found to be normal.

Stridor is a harsh, high-pitched wheezing or vibrating sound that results from turbulent airflow in the upper airways. It can occur during inspiration, expiration, or both, although it most typically occurs during inspiration. While stridor heard mainly during inspiration is often produced in obstructive lesions of the supraglottis or pharynx, stridor originating from obstruction in the thoracic trachea and primary or secondary bronchi, as in our case, is more pronounced on exhalation, since intrathoracic pressure rises on expiration and causes airway collapse.

In view of direct invasion of the trachea by the oesophageal tumour T4bN0M0 (Stage IIIc disease), curative surgical resection is precluded and prognosis is poor.3 The focus of treatment is to palliate the most common sequelae of the disease.4 Even for terminal patients, airway stenting can be a valid palliative care option.5 Unfortunately, in our case, since the tracheal stenting procedure was not available locally and the patient was too unwell to travel overseas, following discussion with the oncologist it was deemed beneficial to palliate with external beam radiation therapy.

Owing to the history of squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus 7 years before, guidelines recommend follow-up visits focusing on symptoms, nutrition and psychosocial problems. Regular long-term follow-up endoscopies are not indicated due to the increased morbidity these might entail.6

Learning points.

Stridor is a medical emergency that requires immediate action to establish the cause and initiate treatment.

The timing of harsh breath sounds in the inspiratory or expiratory phases of the respiratory cycle often helps to localise stridor to an extrathoracic or intrathoracic source.

Oesophageal carcinoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of structural lesions causing stridor, especially when common airway pathology has been excluded.

Such patients should be assessed by multidisciplinary teams on a case by case basis and potential treatment tailored to the specific needs of the individual patient.

Palliative radiation therapy and tracheal stenting are treatment options when curative surgery is not an option and patients should be referred as early as possible to avoid severe discomfort secondary to airway obstruction.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL et al. . SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2002. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strauss A, Pinder M, Lipman J et al. . Acute stridor as a presentation of bilateral abductor vocal cord paralysis. Anaesthesia 1996;51:1046–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1996.tb15002.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, eds. American Joint Committee on cancer staging manual. 7th edn New York: Springer, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman R, Ascioti A, Mahidhara R. Palliative therapy for patients with unresectable esophageal carcinoma. Sur Clin North Am 2012;92:1337–51. 10.1016/j.suc.2012.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kazi A, Flowers W, Barrett J et al. . Ethical issues in laryngology: tracheal stenting as palliative care. Laryngoscope 2014;124:1663–7. 10.1002/lary.24531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stahl M, Budach W, Meyer H et al. . Esophageal cancer: clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2010;21(Suppl 5):v46–9. 10.1093/annonc/mdq163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]