Abstract

Osteomyelitis due to Coxiella burnetii infection is a rare condition in adults. We report the case of a healthy young man presenting with subacute osteomyelitis of the left cheek bone, evolving gradually after an episode of acute febrile illness. Histological evaluation confirmed subacute granulomatous inflammation. Despite antibody titres not reaching the standard cut-off for chronic Q fever (phase I IgG 1/160, phase II IgG 1/2560), osteomyelitis was radiologically and histologically confirmed. A 6-month course of doxycycline/hydroxychloroquine brought clinical and radiological cure while various conventional antibiotic treatments had failed to improve the clinical condition. Currently, at 6-month follow-up, no relapse has occurred and antibody titres have declined. A shorter course of doxycycline/hydroxychloroquine than that used for chronic Q fever osteomyelitis may be sufficient to treat subacute Q fever osteomyelitis in some cases.

Background

We present a case of probable Coxiella osteomyelitis of the cheek bone in a healthy young man without any particular risk factors or known exposure to Coxiella burnetii.

Osteomyelitis is a very rare manifestation of Q fever in adults. Only around 20 cases have been published so far.1–4 A high index of suspicion should be maintained in cases of culture-negative, granulomatous osteomyelitis after ruling out mycobacterial infection,1 2 5 even if there was, as in our patient, no contact with farm animals or pets.1 Clinical suspicion can be confirmed by serology, specific PCR and cell culture,1 2 as well as diagnostic scores, which have recently been proposed for endocarditis, vascular infections and prosthetic joint infections.6–8

Our patient initially presented with an acute febrile illness accompanied by gastrointestinal discomfort and local soft tissue swelling. The initial presentation with local swelling of the cheek is unusual, and not a classical finding in acute C. burnetii infection. Nonetheless, this might have been an atypical presentation of acute Q fever. The ensuing subacute granulomatous osteomyelitis indicates a lack of clearance of the bacteria by the immune system.3 5 9

The inability to find another pathogen in conventional cultures despite an antibiotic-free window of nearly 4 weeks by the time of surgical exploration, the absence of response to various traditional antibiotics and, mostly, the histological evidence of a granulomatous infection, pointed clearly to an atypical pathogen,10 whereas the negative broad-spectrum PCR indicated a low bacterial load, as is often the case in osteomyelitis. Without serological data from a serum sample taken at the beginning of the symptoms and in the absence of a positive PCR result, it was not possible to definitely prove the involvement of Coxiella in this case. However, the presence of IgG phase I and II are compatible with an acute infection having taken place some months earlier. Together with the histopathological findings showing chronic granulomatous inflammation, and the excellent clinical and radiological response to doxycycline/hydroxychloroquine, and declining antibody titres, these findings are highly suggestive of C. burnetii osteomyelitis.

Case presentation

A 23-year-old healthy Caucasian man presented to our outpatient clinic, with a non-healing wound on his left cheek after a surgical incision; the wound had been present for almost 2 months at the time of presentation, despite multiple antibacterial and surgical treatments.

While travelling in Costa Rica, he had developed an acute febrile illness with abdominal discomfort, accompanied by a swelling and mild tenderness of his left cheek. Although the systemic symptoms resolved within a week, the soft tissue swelling of the left cheek persisted. After about 5 weeks, ultrasound of the cheek showed a fluid collection of close to 3 mL, measuring approximately 3×3×0.5 cm, over the cheek bone. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) and, finally, a surgical incision, were performed, draining clear fluid, of which the Gram stain and culture remained negative. While travelling, several empirical per oral antibiotic trials (levofloxacin, cefuroxim, cefpodoxim, combination of cefpodoxim and metronidazol), each lasting 7–10 days, combined with surgical wound care, had failed to improve wound healing.

At the time of the patient's first consultation at our clinic, the soft tissue swelling had been present for almost 3 months; the incision resulting in a non-healing wound had been performed nearly 2 months earlier. Clinical status showed a clean, non-inflamed wound about 1 cm in length, with a palpable, waxy induration around 3×3 cm in the underlying tissues (figure 1). The patient had no other symptoms and there was no sign of orodental infection. Body temperature was normal. Laboratory results showed normal C reactive protein, blood count, liver and kidney function.

Figure 1.

Clinical status at initial presentation showing a clean, non-inflammatory wound about 1 cm in length, with a palpable, waxy induration of the underlying tissue.

Investigations

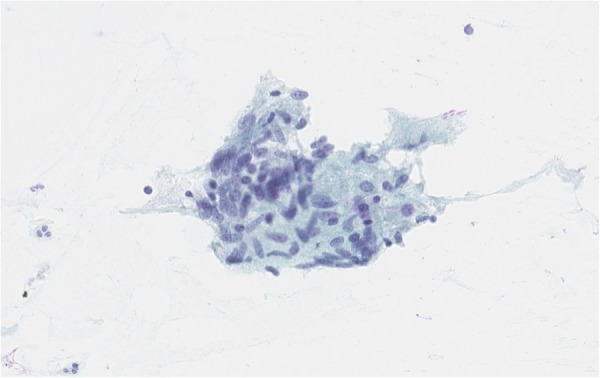

We initially repeated FNA, the cytology of which showed a chronic, focal granulomatous inflammation (figure 2). Gram stain and conventional culture remained negative.

Figure 2.

Cytology: direct smear specimen from fine needle aspirate (FNA) with an aggregate of epithelioid cells, a finding consistent with granulomatous inflammation. Papanicolaou stain (×400).

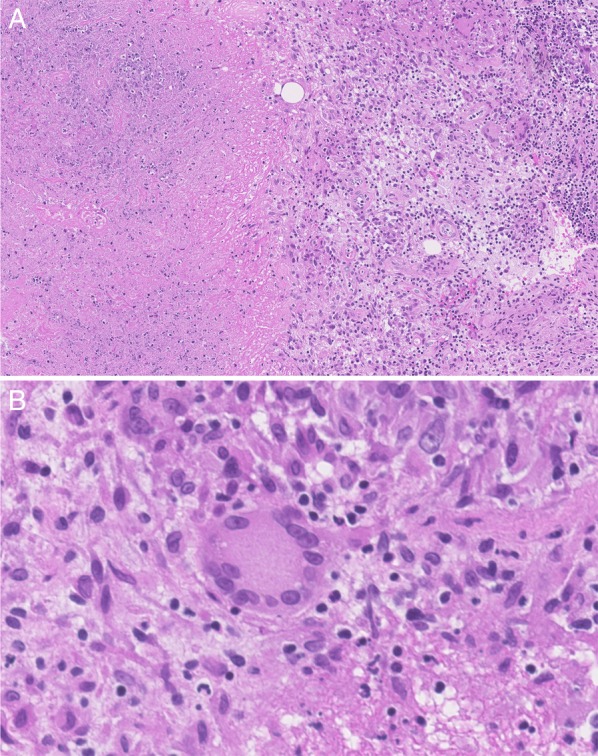

Considering the long history of this unclear soft tissue inflammation, MR tomography of the area was performed, showing soft tissue swelling over the left corpus zygomaticus with central abscess formation of 1×1.5 cm. The abscess extended into the fossa temporalis; additional microabscesses were seen between the temporalis muscle and the corpus zygomaticus. Altered bone marrow signals indicated osteomyelitis of the corpus zygomaticus in the area of the soft tissue swelling (figure 3). Owing to this result, surgical exploration and debridement of the abscess was performed. The histopathological analysis of the surgically removed tissue showed a chronic granulomatous inflammation (figure 4A/B).

Figure 3.

MR tomography (image T1) showing osteomyelitis of the left corpus zygomaticus with altered bone marrow signal (thin arrow) and overlying soft tissue swelling (broad arrow).

Figure 4 (A).

Histology from biopsy material: necrotising chronic granulomatous inflammation with epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells. H&E stain (×150). (B) Histology from biopsy material: giant cell. H&E stain (×150).

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis seemed broad considering this chronic, localised soft tissue swelling with underlying osteomyelitis. All conventional bacterial, mycobacterial and fungal cultures of the intraoperative bone and tissue specimen remained negative despite the patient not being on antibiotic treatment for nearly 4 weeks by the time of surgery. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection was ruled out not only by culture, but also by microscopy and Mycobacterium genus PCR of two separate bone specimens. As all results were negative, we performed eubacterial and panfungal PCR on the intraoperative bone biopsy, which was negative. Considering the symptoms had begun in Costa Rica, specific PCR for Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas Disease) had been performed on the initial FNA-Material. HIV-infection and syphilis had been ruled out serologically. We completed our work up with serologies for T. cruzi, Leishmania, Rickettsia, Francisella tularensis and Cryptococcus, all of which were negative. Considering the granulomatous nature of the soft tissue inflammation, serologies for C. burnetii, Bartonella henselae and Brucella were performed, the latter two being negative.

Antibody titres for C. burnetii were measured by indirect immunofluorescence assay, using purified phase I and phase II antigens (Rocky Mountains Laboratories, Hamilton, USA, O Péter, personal communication). Titres were moderately elevated for IgG phase II (1/2560) and IgG phase I (1/160), and negative for IgM phase I and II. A specific C. burnetii real-time PCR targeting the insertion element IS1111, adapted from Tilburg et al,11 performed on the intraoperative biopsy, remained negative. We repeated the serology 2 months later, and found essentially identical titres compared to the earlier sample.

The widely accepted serological cut-off for endovascular chronic Q fever is phase I IgG >1/800.1–3 5 9 This cut-off yields a positive predictive value of 98% for chronic Q fever endocarditis.4 12 It has, however, to be mentioned that such cut-offs have never been determined for Q fever osteomyelitis. The cut-off was not reached by our patient, but, as demonstrated by Edouard et al13 for endovascular infection, the diagnosis of Q fever infection should not be excluded in patients with low titres of phase I IgG. Moreover, the proportion of positive qPCR results increases with elevated antibody titres, and might remain negative due to sampling errors in cases of confined infection.13

We considered the initial acute febrile episode as a possible acute C. burnetii infection (compatible with serology), and judged the subacute, granulomatous osteomyelitis to be a persistent focalised C. burnetii infection, as it has been described in patients with low antibody titres.13

Treatment

Treatment of chronic Q fever is best studied in endocarditis. Today, a combination of doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine is considered the standard therapy.2 10 12 14 The duration of treatment of chronic osteomyelitis is not clearly defined.1 4 In analogy to chronic endocarditis, treatment duration of 18 months is recommended.1 2 4 10

A treatment with doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine was initiated. We monitored serum levels of doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine in order to ensure optimal treatment.3 10 12 After 1 month of treatment, drug titres remained low (doxycycline 2.6 mg/L, hydroxychloroquine 0.1 mg/L). According to the literature,3 4 10 12 outcome is better with serum concentrations for doxycycline >5 mg/L and hydroxychloroquine 0.8–1.2 mg/L. After adjusting the doses, serum concentrations were 4.0–8.2 mg/L for doxycycline and 0.27–0.6 mg/L for hydroxychloroquine. Treatment was well tolerated except for photohypersensitivity, for which the patient was advised to wear sunscreen daily and mostly avoid outdoor activities.

Outcome and follow-up

After 3 months of antibiotic treatment, clinical improvement was evident and, after 5 months of treatment, the wound had closed (figure 5). Considering our patient's excellent clinical response, we decided to stop treatment after 6 months in analogy to published cases in children.2 3 Serology performed at 3 months of treatment showed falling titres for IgG phase II (1/640) and IgG phase I (1/80), whereas IgM phase I and II remained negative. Follow-up 3 months after stopping antibiotics showed unchanged serological titres. MR tomography performed at 3 months of treatment showed only moderately improved inflammation, whereas follow-up MRI performed 3 months after stopping of antibiotics revealed an almost normal bone signal on MRI.

Figure 5.

Healed scar after 6 months of treatment.

After 6 months of follow-up, there was no sign of relapse in clinical, serological and MRI results, indicating sufficient therapy. We will continue to evaluate the patient clinically and serologically 3–6 monthly.

Discussion

First described in 1935 by Edward Derrick in Brisbane, Australia, C. burnetii, a small Gram-negative obligate intracellular bacterium, is well known today as a ubiquitous zoonosis.1 9 10 The main reservoirs are farm animals and pets. Infection of humans occurs via inhalation of infected aerosols.5 9 As dormant forms of the bacteria can survive in the environment and are easily spread by the wind, infection can take place far away from the original source.1 3 9

The disease is mostly asymptomatic. In approximately 40% of adults, acute Q fever manifests with mild flu-like symptoms, pulmonary symptoms, hepatitis and fever, whereas 50–80% of children present with gastrointestinal symptoms and rash.9 Acute Q fever is serologically characterised by IgG and IgM antibodies against phase II appearing within a few weeks. Treatment of choice is doxycycline for 2–3 weeks.2 9

Chronic Q fever develops in only 1–2% of patients; the most common presentations in adults are endocarditis (60–70%), endovascular infection, pulmonary infection and, very rarely, osteoarticular infection.1 3 4 In children, endocarditis and osteomyelitis is most common.2 Diagnosis of chronic Q fever is, serologically, characterised by high titres of phase I antibodies, and by proposed diagnostic scores.6–8 Treatment of chronic Q fever is a combination of doxycycline/hydroxychloroquine for many months to years.2 14

Even though definite proof for a C. burnetii-associated osteomyelitis in this patient is lacking, we believe that circumstantial evidence (history of an acute febrile illness with ensuing subacute granulomatous osteomyelitis, serological prove of (past) acute Q-fever, clinical and radiological cure after receiving doxycycline/hydroxychloroquine) together with new findings of persistent focalised Q-fever infections with low phase I IgG support this diagnosis.

As this case demonstrates, the diagnosis of Coxiella osteomyelitis should be considered in culture negative, granulomatous osteomyelitis, particularly in the absence of an alternative explanation and non-response to standard antibiotics, even if the widely accepted serological cut-off (phase I IgG >1/800) or the proposed diagnostic scores are not met.

Given the rarity of Q fever osteomyelitis, the optimal choice of treatment and treatment duration is—and will likely remain—to be extrapolated from case reports and analogue conditions (chronic Q fever endocarditis). As illustrated in our case, a shorter course of doxycycline/hydroxychloroquine may be sufficient to treat subacute Q fever osteomyelitis in some cases.

Learning points.

Consider Coxiella burnetii osteomyelitis in culture negative, granulomatous osteomyelitis.

The diagnosis of persistent Q fever infection should not be excluded in patients with low titres of phase I IgG.

A shorter course of doxycycline/hydroxychloroquine may be sufficient to treat subacute Q fever osteomyelitis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Irene Abela, Institute of Infectious Diseases, University Hospital Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland, and Dr Christine Pretzl, Institute of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University Hospital Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland, for excellent patient care.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Merhej V, Tattevin P, Revest M et al. Q fever osteomyelitis: a case report and literature review. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2012;35:169–72. 10.1016/j.cimid.2011.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landais C, Fenollar F, Constantin A et al. Q fever osteoarticular infection: four new cases and a review of the literature. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2007;26:341–7. 10.1007/s10096-007-0285-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nourse C, Allworth A, Jones A et al. Three cases of Q fever osteomyelitis in children and a review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:e61–6. 10.1086/424014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acquacalda E, Montaudie H, Laffont C et al. A case of multifocal chronic Q fever osteomyelitis. Infection 2011;39:167–9. 10.1007/s15010-010-0076-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fournier PE, Marrie TJ, Raoult D. Diagnosis of Q fever. J Clin Microbiol 1998;36:1823–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wegdam-Blans MC, Kampschreur LM, Delsing CE et al. Chronic Q fever: review of the literature and a proposal of new diagnostic criteria. J Infect 2012;64:247–59. 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raoult D. Chronic Q fever: expert opinion versus literature analysis and consensus. J Infect 2012;65:102–8. 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Million M, Bellevegue L, Labussiere AS et al. Culture-negative prosthetic joint arthritis related to Coxiella burnetii. Am J Med 2014;127:786.e7–10. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delsing CE, Warris A, Bleeker-Rovers CP. Q fever: still more queries than answers. Adv Exp Med Biol 2011;719:133–43. 10.1007/978-1-4614-0204-6_12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raoult D, Houpikian P, Tissot Dupont H et al. Treatment of Q fever endocarditis: comparison of 2 regimens containing doxycycline and ofloxacin or hydroxychloroquine. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:167–73. 10.1001/archinte.159.2.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tilburg JJ, Melchers WJ, Pettersson AM et al. Interlaboratory evaluation of different extraction and real-time PCR methods for detection of Coxiella burnetii DNA in serum. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:3923–7. 10.1128/JCM.01006-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lecaillet A, Mallet MN, Raoult D et al. Therapeutic impact of the correlation of doxycycline serum concentrations and the decline of phase I antibodies in Q fever endocarditis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009;63:771–4. 10.1093/jac/dkp013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edouard S, Million M, Lepidi H et al. Persistence of DNA in a cured patient and positive culture in cases with low antibody levels bring into question diagnosis of Q fever endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol 2013;51:3012–17. 10.1128/JCM.00812-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Million M, Thuny F, Richet H et al. Long-term outcome of Q fever endocarditis: a 26-year personal survey. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10:527–35. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70135-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]