Abstract

The aims of this study were to assess that the effects of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) combination with minocycline improve spinal cord injury (SCI) in rat model. In the present study, the Wistar rats were randomly divided into five groups: control group, SCI group, BMSCs group, Minocycline group and BMSCs + minocycline group. Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan (BBB) test and MPO activity were used to assess the effect of combination therapy on locomotion and neutrophil infiltration. Inflammation factors, VEGF and BDNF expression, caspase-3 activation, phosphorylation-p38MAPK, proNGF, p75NTR and RhoA expressions were estimated using commercial kits or western blot, respectively. BBB scores were significantly increased and MPO activity was significantly undermined by combination therapy. In addition, combination therapy significantly decreased inflammation factors in SCI rats. Results from western blot showed that combination therapy significantly up-regulated the protein of VEGF and BDNF expression and down-regulated the protein of phosphorylation-p38MAPK, proNGF, p75NTR and RhoA expressions in SCI rats. Combination therapy stimulation also suppressed the caspase-3 activation in SCI rats. These results demonstrated that the effects of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells combination with minocycline improve SCI in rat model.

Keywords: Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, minocycline, spinal cord injury, inflammation, VEGF and BDNF

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) refers to complete or incomplete spinal cord motor, sensory, sphincter and autonomic dysfunctions resulted from the violent attack on spinal cord, which is devastating disease in orthopedics and causes serious physiological and psychological damage to the patients [1]. In most countries, SCI incidence rate is 20 to 40 per million people [2]. The main reasons of SCI include traffic accidents (45.4%), falls (16%) and sports injuries (16.3%) [3]. So far, the results indicate the final neurological damage of SCI is caused by two mechanisms, namely primary injury and secondary injury. Primary injury refers to tissue damage caused instantly by the mechanical force in spinal cord tissue, and the resulted nerve damage is irreversible; a series of self-destruction destruction processes in which pathological factors aroused by primary injury participate are called secondary injuries, of which the evolution lasts up to a few hours to a few weeks [4]. This is an active adjustment process of the cell and molecular levels, reversible and able to be controlled. Sometimes the extent of tissue damage produced by secondary injury is even more than that of primary injury [5].

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (BMSC) is a stem cell with potential of multi-directional differentiation and researches have confirmed, BMSC transplantation for the treatment of SCI is feasible, but the simple effect of BMSC transplantation therapy on SCI is limited, so after BMSC is directionally induced to differentiate into neuron-like cell, the transplantation therapy for SCI has important research value [6,7]. This is taken as basis for project, and SCI rat model is designed to study different results for SCI by the transplantation treatment that different inducers lead to the differentiation of BMSC into neuron-like cells, providing theoretical basis for the clinical treatment of SCI [8]. Minocycline is a second-generation semi-synthetic tetracycline class of drug, with not only a strong antibacterial effect, but also significant anti-inflammatory effect [9]. In recent years, studies have shown that inhibiting the activity of minocycline has significant neuroprotective function for the ischemia in brain tissue [10].

However, the effects of BMSCs combination with minocycline on SCI remain uncharacterized. In our research, we explored whether the effects of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells combination with minocycline improves SCI in rat model. We also studied the molecular mechanism of the protective effect of the combination therapy on articular cartilage damage, inflammation response and apoptosis in rat model of SCI.

Methods

Chemicals

Modified Eagle Medium (MEM), Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were provided from Sigma (Germany). Minocycline (with a purity >95%) was purchased from Nanjing Traditional Chinese medicine Institute of Chinese Material Medica (Nanjing, China). Myeloperoxidase (MPO), Microvessel density (MVD), Nuclear transcription factor-kappa (NF-κB) p65 unit, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and caspase-3 commercial kits were purchased from Beyotime (Nanjing, China).

Animals

Male Sprague Dawley rats and adult female Wistar rats (250-300 g) were purchased from the Center for Experimental Animals of Central South University (Changsha, China). All rats were carried out in accordance with national Institute of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All rats were maintained under a 12 h dark/light cycle, at 22-24°C, relative humidity 40-60% and allowed food and water.

Cell culture and haemotoxylin staining of BMSCs

2-3 mL of bone marrow was isolated in sterile conditions from Sprague Dawley rats as described as document [11]. BMSCs were isolated from bone marrow and cultured as described by previous document [12]. Overdose of pentobarbital was injected into Sprague Dawley rats, and the tibia and femur were separated out. The bones were cut off and marrow was flushed out using 5 ml of α-MEM with a 25-gauge needle. Followed by centrifugation at 1000 r/m for 5 min, the supernatant was discarded. The cells were placed into 25 cm2 plastic flask and then cultivated in 5 mL of DMEM including 15-20% of FBS at 37°C in humidified atmosphere 5% CO2 for 24 h. Then, non-adherent cells were removed by replacing new culture medium. After 48 hours, the non-adherent cells were removed by replacing new culture medium. When adherent cells grew to 80-90% confluency, then these cells were removed and incubated with 0.25% trypsin and 1 mM EDTA at 37°C for 5 minutes and passaged. Using this method, BMSCs were sub-cultured 4 times. The cells were labeled with 3 µg/ml of bromodeoxyuridine and incubated for 3 days.

BMSCs was washed with twice PBS and fixed with 4% of paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Then, haemotoxylin (Beyotime, Nanjing, China) was added into the fixation cell and cultured for 3-10 min according to previous literature [12]. Staining cell was washed with tap-water for 10 min and then again washed with distilled water at a time. 95% ethyl alcohol was used to dehydrate staining cell for 2 min and then xylene was used to transparent staining cell for 5 min. Neutral balsam was used to mount medium and observed using microscope (CFI60, Nikon, Japan).

Spinal cord injury model

The SCI rat model was executed as described previously [13]. The Wistar rats were anesthetized using intraperitoneal ketamine (80 mg/ kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Then, rats were executed a laminectomy during which the T8 and T9 vertebral peduncles were removed. The control rats were carried out the same laminectomy without compression.

Transplantation procedure

The rats were randomly divided into five groups: control group, SCI group, BMSCs group, Minocycline group and BMSCs + minocycline group (Therapy). Control group (n=12) in which only a laminectomy was performed; SCI group (n=12) in which serum was administered by intraspinal injection (i.i.); BMSCs group (n=12) in which BMSCs (3×105) by i.i. using Hamilton syringe described as document [7] for 14 days; Minocycline group (n=12) in which [14] received minocycline (50 mg/kg) daily for 14 days; BMSCs + minocycline group, in which BMSCs (3×105) by i.i. and minocycline (50 mg/kg) daily for 14 days.

Evaluation of neuronal function recovery

After combination therapy, the evaluation of neuronal function recovery was evaluated by the Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan (BBB), locomotor rating scale of 0 (no observable hind-limb movements) to 21 (normal locomotion) [15].

Evaluation of programmed cell death using eosin (H&E) staining

After combination therapy, spinal cord samples of each group were collected and sliced up sections of spinal cord. Then, these sections were stained in hematoxylin solution for 10 min and differentiated in 1% acid-alcohol for 30 s. These sections were stained with H&E for 30 s and dehydrated with alcohol for 2 min each. These sections were covered with xylene-based mounting medium after two changes of xylene.

MPO activity

After combination therapy, SCI tissue was rapidly acquired. Followed by centrifugation at 12000 r/m for 10 min, the supernatant was discarded. MPO activity was defied as the quantity of enzyme degrading and was expressed in unit g-1 of wet tissue following the manufacturer’s protocol (Beyotime, Nanjing, China).

Inflammation factors

After combination therapy, SCI tissue was rapidly acquired. Followed by centrifugation at 12000 r/m for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was discarded. The supernatant was used to assess activities of NF-κB p65 unit and TNF-α, following the manufacturer’s protocol (Beyotime, Nanjing, China).

Western blot

After combination therapy, SCI tissue was rapidly acquired. SCI tissue was prepared by rapid homogenization in 10 volumes of lysis buffer and the supernatant was discarded after centrifugation at 12000 r/m for 10 min at 4°C. The protein concentration was determined by the Coomassie (G250) binding method. 20 μg of protein were loaded for separated into 10% gradient SDS-PAGE under denaturing conditions and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc). The sections were blocked with PBS with non-fat milk for 1-2 h at room temperature and then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by anti-vascularendothelial growth factor (VEGF, 1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Calif, USA), anti-BDNF (1:2000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Calif, USA), anti-phosphorylation-p38MAPK (p-p38-MAPK, 1:1500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Calif, USA), anti-Pro-Nerve Growth Factor (proNGF, 1:1500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Calif, USA), anti-p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR, 1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Calif, USA), anti-RhoA and anti-β-actin (1:500, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China).

Caspase-3 activation assay

After combination therapy, SCI tissue was rapidly acquired. Followed by centrifugation at 12000 r/m for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was discarded. Then supernatant were collected to measure the protein concentration with using a BCA kit (Beyotime, Nanjing, China). Equal protein was incubated with reaction buffer (Ac-LEHD-pNA) at 37°C for 2 h in the dark and then activities were measured at an absorbance of 405 nm.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test, and performed using Excel 2007 software package (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

Results

BMSC cell culture and detection

In initial experiments, morphology of the primary BMSCs were cultured and appeared homogeneous and multiplicity, which showed spindle-shaped with serial sub-cultivation (Figure 1). The results of haemotoxylin staining showed that cell nucleus appeared mazarine (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

BMSC cell culture and detection. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells were culture, detected using haemotoxylin staining and observed using microscope.

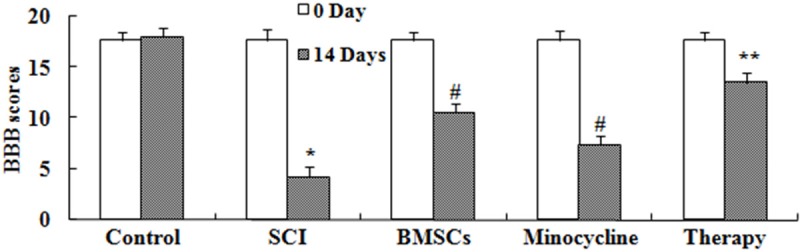

Effect of combination therapy improve functional recovery after SCI

We investigated whether the effect of combination therapy affected on the functional recovery after SCI. These results of BBB showed that SCI could lead to descend BBB scores compared to that of control group (Figure 2). As shown in Figure 2, only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated effectively increased BBB scores in SCI rats, respectively. However, BBB scores of combination therapy were higher than only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of combination therapy improve functional recovery after SCI. Control, control group; SCI, SCI group; BMSCs, BMSCs group; Minocycline, Minocycline group; Therapy, Minocycline group and BMSCs + minocycline group. **P<0.01 versus control group; #P<0.05 versus SCI group; ##P<0.05 versus SCI group.

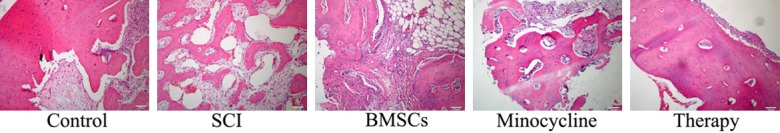

Effect of combination therapy on programmed cell death after SCI

We observed whether the effect of combination therapy affected on programmed cell death after SCI. As shown in Figure 3, the programmed cell death in SCI rat was higher than that of control. Only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated observably inhibited the programmed cell death of SCI, respectively (Figure 3). Combination therapy could reduce the programmed cell death in SCI rat, compared to only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of combination therapy on programmed cell death after SCI. Control, control group; SCI, SCI group; BMSCs, BMSCs group; Minocycline, Minocycline group; Therapy, Minocycline group and BMSCs + minocycline group. **P<0.01 versus control group; #P<0.05 versus SCI group; ##P<0.05 versus SCI group.

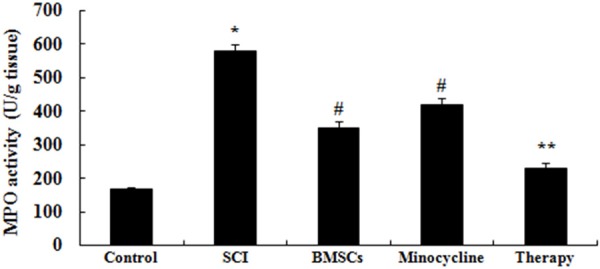

Effect of combination therapy on neutrophil infiltration after SCI

We further investigated whether the effect of combination therapy affected on neutrophil infiltration after SCI, MPO activity was measured in our study. In SCI tissue, MPO activity was observably elevated in comparison with that of control group (Figure 4). Meanwhile, only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated observably reduced this change compared to that of SCI group (Figure 4). However, this change was enlarged by treated with combination therapy in comparison with that of only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of combination therapy on neutrophil infiltration after SCI. Control, control group; SCI, SCI group; BMSCs, BMSCs group; Minocycline, Minocycline group; Therapy, Minocycline group and BMSCs + minocycline group. **P<0.01 versus control group; #P<0.05 versus SCI group; ##P<0.05 versus SCI group.

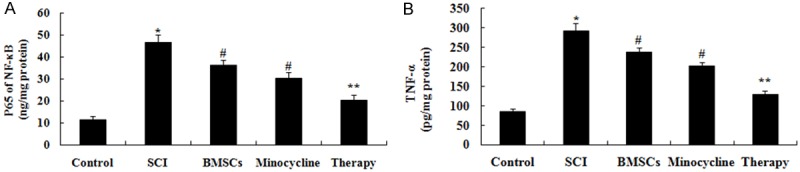

Effect of combination therapy on inflammation after SCI

We explored the possible mechanisms of combination therapy on SCI, inflammation factors were examined in this study. In comparison with control group, activities of NF-κB p65 unit and TNF-α were markedly induced by SCI (Figure 5A, 5B). After only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated, activities of NF-κB p65 unit and TNF-α were markedly inhibited these inflammation factors compared to that of SCI group (Figure 5A, 5B). However, these inflammation factors in combination therapy group were lower than those of only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated group (Figure 5A, 5B).

Figure 5.

Effect of combination therapy on inflammation after SCI. Effect of combination therapy on the activities of NF-κB p65 unit and TNF-α after SCI. Control, control group; SCI, SCI group; BMSCs, BMSCs group; Minocycline, Minocycline group; Therapy, Minocycline group and BMSCs + minocycline group. **P<0.01 versus control group; #P<0.05 versus SCI group; ##P<0.05 versus SCI group.

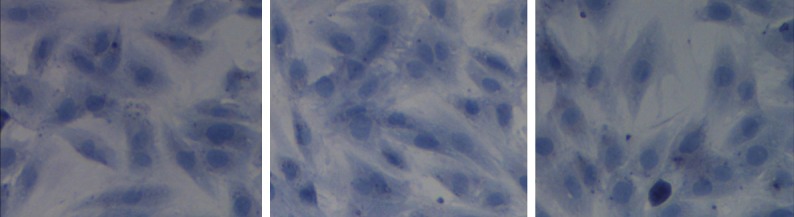

Effect of combination therapy on VEGF and BDNF expression level after SCI

We probed the possible mechanisms of combination therapy on SCI, VEGF and BDNF expression level were analyzed using western blot. These results of western blotting showed that the protein expression of VEGF and BDNF were signally suppressed in SCI model group in comparison with those of control group (Figure 6A-D). In SCI tissues, the expression of VEGF and BDNF protein were signally increased by only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated (Figure 6A-D). However, combination therapy signally accelerated this therapeutic effect on VEGF and BDNF in SCI rats (Figure 6A-D).

Figure 6.

Effect of combination therapy on VEGF and BDNF expression level after SCI. Effect of combination therapy on VEGF and BDNF protein expression (A and C) using Western blotting assays and statistical analysis of VEGF and BDNF protein expression level (B and D) after SCI. Control, control group; SCI, SCI group; BMSCs, BMSCs group; Minocycline, Minocycline group; Therapy, Minocycline group and BMSCs + minocycline group. **P<0.01 versus control group; #P<0.05 versus SCI group; ##P<0.05 versus SCI group.

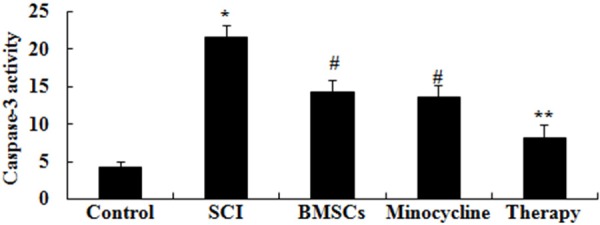

Effect of combination therapy on caspase-3 activation after SCI

We research the possible mechanisms of combination therapy on SCI was in contact with cell apoptosis, caspase-3 activation was measured in our study. As shown in Figure 7, the activity of caspase-3 was memorably augmented in SCI rats compared to control rats. After only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated, caspase-3 activity was memorably restrained compared to that of SCI group (Figure 7). Interesting, caspase-3 activity of combination therapy was lower than that of only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Effect of combination therapy on caspase-3 activation after SCI. Control, control group; SCI, SCI group; BMSCs, BMSCs group; Minocycline, Minocycline group; Therapy, Minocycline group and BMSCs + minocycline group. **P<0.01 versus control group; #P<0.05 versus SCI group; ##P<0.05 versus SCI group.

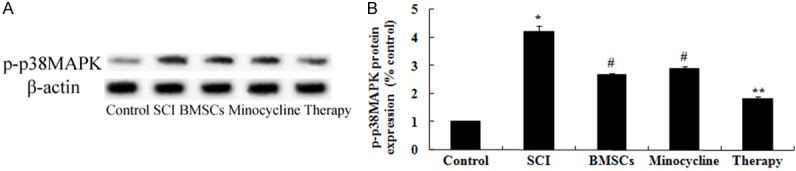

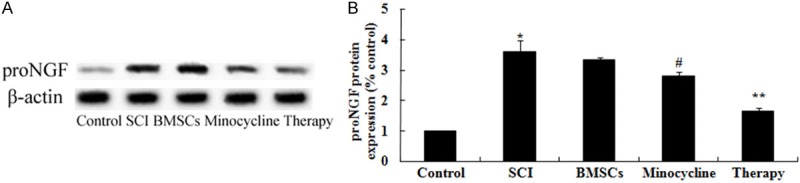

Effect of combination therapy on p38MAPK-dependent proNGF expression

In order to detect the possible mechanisms of combination therapy on SCI, p-p38MAPK protein expression was analyzed by western blot. These results of western blotting showed that SCI significantly activated the protein expression of p-p38MAPK in SCI rats compared to that of control group (Figure 8A, 8B). Interesting, only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated significantly reduced the promotion of p-p38MAPK protein expression in SCI rats (Figure 8A, 8B). After combination therapy, the p-p38MAPK protein expression was lower than that of only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated (Figure 8A, 8B).

Figure 8.

Effect of combination therapy on p38MAPK-dependent proNGF expression. Effect of combination therapy on p-p38MAPK protein expression using Western blotting assays and statistical analysis of p-p38MAPK protein expression level. Control, control group; SCI, SCI group; BMSCs, BMSCs group; Minocycline, Minocycline group; Therapy, Minocycline group and BMSCs + minocycline group. **P<0.01 versus control group; #P<0.05 versus SCI group; ##P<0.05 versus SCI group.

Effect of combination therapy on proNGF expression after SCI

In order to probe the possible mechanisms of combination therapy on SCI, proNGF expression was detected by western blot. As shown in Figure 9A, 9B, the protein expression of proNGF was dramaticlly promoted by SCI compared to control rats. Nevertheless, only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated dramatically remitted this tendency in SCI rats (Figure 9A, 9B). Meanwhile, this tendency in combination therapy group was dramatically receded in comparison with that of only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated group (Figure 9A, 9B).

Figure 9.

Effect of combination therapy on proNGF expression after SCI. Effect of combination therapy on proNGF protein expression using Western blotting assays and statistical analysis of proNGF protein expression level. Control, control group; SCI, SCI group; BMSCs, BMSCs group; Minocycline, Minocycline group; Therapy, Minocycline group and BMSCs + minocycline group. **P<0.01 versus control group; #P<0.05 versus SCI group; ##P<0.05 versus SCI group.

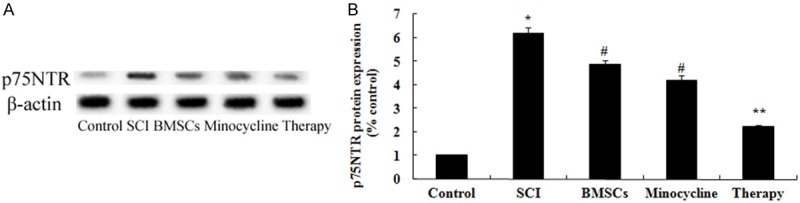

Effect of combination therapy on p75NTR expression after SCI

In order to investigate the possible mechanisms of combination therapy on SCI was in contact with p75NTR expression after SCI, p75NTR expression was performed by western blot. These results of western blotting showed that the protein expression of p75NTR in SCI rat was significantly activated compared to that of control group (Figure 10A, 10B). Moreover, only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated could significantly suppress the p75NTR protein expression in SCI rats (Figure 10A, 10B). But, curative effect of combination therapy on the p75NTR protein expression was precede only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated (Figure 10A, 10B).

Figure 10.

Effect of combination therapy on p75NTR expression after SCI. Effect of combination therapy on p75NTR protein expression using Western blotting assays and statistical analysis of p75NTR protein expression level. Control, control group; SCI, SCI group; BMSCs, BMSCs group; Minocycline, Minocycline group; Therapy, Minocycline group and BMSCs + minocycline group. **P<0.01 versus control group; #P<0.05 versus SCI group; ##P<0.05 versus SCI group.

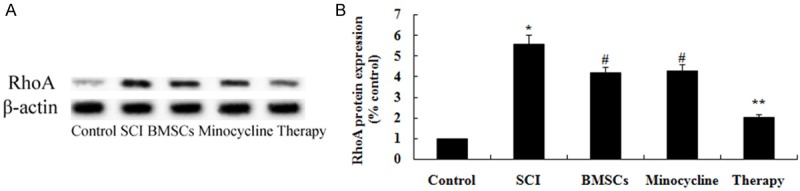

Effect of combination therapy on RhoA expression after SCI

In order to explore the possible mechanisms of combination therapy on SCI, RhoA expression was performed by western blot. As shown in Figure 11A, 11B, the protein expression of RhoA was memorably enhanced by SCI compared to that of control group. After treatment with only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated, the protein expression of RhoA was memorably weakened in SCI rats (Figure 11A, 11B). Nevertheless, combination therapy memorably weakened the RhoA protein expression in comparison with that of only BMSCs-treated or only minocycline-treated (Figure 11A, 11B).

Figure 11.

Effect of combination therapy on RhoA expression after SCI. Effect of combination therapy on RhoA protein expression using Western blotting assays and statistical analysis of RhoA protein expression level. Control, control group; SCI, SCI group; BMSCs, BMSCs group; Minocycline, Minocycline group; Therapy, Minocycline group and BMSCs + minocycline group. **P<0.01 versus control group; #P<0.05 versus SCI group; ##P<0.05 versus SCI group.

Discussion

After SCI, secondary pathological changes will increase the SCI, and even cause irreversible damage to the spinal cord. Ischemia is an important factor to cause secondary injury in spinal cord [16]. After SCI, the spinal cord blood flow declines or even stops completely. Due to the reduction in blood supply, oxygen supply is reduced as well so that the process of oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria of cells slows down, reducing the metabolic activity due to the lack of sufficient oxygen and energy in cell, thereby causing necrosis of the spinal cord and loss of nerve function [17]. The reperfusion after ischemia further aggravates SCI and shortening ischemic time is the key to reduce the ischemia-reperfusion injury [18]. Free radicals and Ca2+ are important factors to cause SCI [19]. Lipid free radicals reactions in membrane have changed membrane structure and function significantly, which not only destroys the selective permeability of membrane, but also inhibits the activity of a number of important enzyme systems. Meanwhile free radicals also cause microvascular occlusion and spasm, thus causing delayed ischemia [20]. Our results showed that the effect of BMSCs combination with minocycline improved functional recovery and reduced neutrophil infiltration after SCI in rat. In addition, Nandoe Tewarie et al. reported that BMSCs repairs spinal cord in vitro and in vivo studies [21]. Lee et al. revealed that minocycline improves functional recovery and alleviates cell death after traumatic SCI in the rat [22]. Our data demonstrates that the effect of BMSCs combination with minocycline can improve functional recovery in SCI rat.

After acute SCI, the mechanism of secondary SCI is very complex. The degree of self-destruct sequence destruction in which multiple factors participate on the basis of primary injury is even more than that of primary injury [23]. Pathological change of secondary SCI is the result of a variety of factors, including: the vascular factor, the role of free radicals, the toxic effect of excitatory amino acids, the inflammation and the apoptosis. Inflammation is one of the main mechanisms of secondary SCI after acute SCI [24]. Our result showed that the effect of BMSCs combination with minocycline could suppress inflammation factors after SCI in rat. One study showed that BMSCs attenuate lung inflammation of neonatal rats [25]. Kim et al. reported that minocycline has been clinically tried for spinal cord injury through suppression of inflammation [26]. Our result showed that the effect of BMSCs combination with minocycline can suppress inflammation factors after SCI, which further confirmed the combination therapy improve SCI and its related mechanisms in treatment nervous disease.

VEGF is a specific polypeptide glycoprotein promoting vascular endothelial growth and angiogenesis, which has also been proved to express in activated neural cells. Currently it is considered that VEGF is also a neuroprotective factor, to protect nerve cells directly through an independent mechanism, not dependent on angiogenesis [27]. VEGF can promote stem cell proliferation in the development of central nervous system, in addition to the direct effect of nutrition nerves [28]. BDNF has the functions of maintenance and promotion for the development differentiation and the regeneration and growth of various sensory neurons, cholinergic neurons, dopaminergic neurons as well as GABA neurons [29]. BDNF does not work for sympathetic and ciliary ganglion, but it can prevent the death of a lot of movement neurons after the cross of sciatic nerve, and can save red nucleus neurons after the half cut of SCI [30]. Studies have shown that BDNF is involved in repair process of spinal cord, saving the neurons in SCI by use of BDNF has great potential [31]. Our result showed that the effect of BMSCs combination with minocycline could increase the VEGF and BDNF expression level after SCI in rat. One study showed that BMSCs attenuate lung inflammation of neonatal rats [25]. Kim et al. reported that minocycline has been clinically tried for spinal cord injury through suppression of inflammation [26]. Kamei et al. suggested that BMSCs promotes corticospinal axon growth through BDNF and VEGF in organotypic cocultures in neonatal rats [32]. These studies explained the mechanism of BMSCs combination with minocycline can promotes the VEGF and BDNF expression after SCI, which further confirmed the combination therapy augment the blood vessel formation in SCI rat.

Caspase-3 is the most important protease during apoptosis, which is the downstream effector part of multiple apoptotic pathways, as the only way of protease cascade of cell apoptosis [31]. Under normal circumstances, caspase-3 protein is synthesized in the form of very low activity of plasminogen, which is activated by the removal of a sequence of amino acid by hydrolysis [33]. Research has shown that caspase-3 activity is increased in ischemic and traumatic SCI animal models. Simple increased caspase-3 protein does not directly explain the increase of caspase-3 with activity. So we measure the activity change of caspase-3 in the occurrence stage of apoptosis by enzyme-linked fluorescence assay [34]. Experiments have confirmed neuronal death begins soon by apoptotic way and lasts a long period of time after SCI. Caspase-3 activity change, caspase-3 protein expression and apoptosis are consistent over time, suggesting caspase-3 is involved in the regulation of SCI apoptosis, from which it can be seen that the increased expression of caspase-3 may play an important role in the development of SCI [35]. In this study, we found that the effect of combination therapy relieved the caspase-3 activation in rat after SCI. Zhang et al. reported that BMSCs protect oxygen-glucose deprivation injury through decreasing oligodendrocytes apoptosis caspase-3 expressions [36]. Abcouwer et al. indicated that minocycline prevents retinal inflammation and vascular permeability, and suppresses the caspase-3 activation in ischemia-reperfusion injury rat [37]. In this study, our study hinted that the effect of BMSCs combination with minocycline on SCI may be applies to the suppression of caspase-3 activation in rat.

MAPK signal pathway is composed of multiple protein kinases by delivery times, of which the basic function is to feel the extracellular stimulating signals, and in turn stimulating the adaptive responses of intracellular metabolism and biochemistry of organisms, leading to the change in cell function [38]. MAPK signal pathway is the intersection and common pathway of the information transmission that the signals related to cell growth stimulate vertebrate animal cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation of cells [39]. P38MAPK participates in signal transduction in the process of neuronal apoptosis. An increase in the expression of p-p38MAPK can be seen in the apoptosis of redundant nerve and glial cells after SCI, indicating the presence of the change in p38MAPK signal transduction pathway after SCI [40].

ProNGF is a member of the neurotrophic factor family, as an important factor in the maintenance of normal nervous system development and function, which plays an important regulatory role in the growth and differentiation of nerve cells, participating in the regeneration and repair of nerve injury [41]. The biggest obstacle in proNGF application to neurological diseases is that direct intravascular administration cannot be realized, because it belongs to biological macromolecules, not easy to cross the blood-brain barrier [42]. According to the research of proNGF transfected into fibroblasts in rats after SCI by local transplantation, NGF produced by somatic cell transfer is an effective means to promote axonal regeneration [43]. In the present study, we found that the effect of combination therapy suppressed the p-p38MAPK and proNGF protein expressions in SCI rat. Furthermore, Yang et al. indicated that treatment with BMSCs inhibits the p-p38MAPK in acute myeloid leukemia [44]. Yune et al. suggested that minocycline treatment inhibits proNGF production through inhibition of the p-p38MAPK [1]. In the present study, we found that the effect of BMSCs combination with minocycline suppresses p38MAPK-dependent proNGF expression in SCI rat.

P75NTR is a glycoprotein with molecular weight of 75 kD, of which the function is very complicated, playing an important role in the development of nervous system, axonal regeneration and synaptic plasticity. As a low-affinity neurotrophin receptor, it facilitates the integration with Trk receptors to further enhance neurotrophic factor function; moreover, as a co-receptor of Nogo-66 receptor NgR, it regulates the signal expression of nerve projections degeneration caused by growth inhibition factors [45]. After peripheral nerve injury, p75NTR expression in DRG sensory neurons falls down but increases in glial cells; up-regulated expression of p75NTR in glial cells is considered to be related to the prevention of damaged neurons from apoptosis after binding to BDNF [46,47].

Growth-inhibiting factor and its related suppression signal is a hot research direction in the field of central nervous system regeneration in recent years. There are few reports currently about whether olfactory ensheathing cells have influence on axons inhibitors and their related inhibiting signal RhoA at home and abroad [48]. A molecular biology method is applied to indicate preliminarily the transplantation of olfactory ensheathing cells can reduce the expression level of RhoA protein in SCI area, which may be an important mechanism for treating SCI by olfactory ensheathing cell transplantation [49]. In our study, we found that the effect of combination therapy weakens the protein of p75NTR and RhoA expressions after SCI. Edalat et al. showed that BMSCs reduced apoptosis through suppression of p75NTR during neural differentiation in rat [50]. Yune et al. suggested that minocycline impairs death of oligodendrocytes through inhibiting p75NTR and RhoA expressions after SCI [1].

In conclusion, we conclude that the positive effects of BMSCs combination with minocycline on the improved functional through anti-inflammation, activation of VEGF and BDNF, anti-apoptosis, suppression of p38MAPK-dependent proNGF expression, and suppression of p75NTR and RhoA in SCI rat. These results imply that the positive effects of BMSCs combination with minocycline may represent a promising strategy for clinically applicable therapy for initiation of neuroprotection after SCI.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Yune TY, Lee JY, Jung GY, Kim SJ, Jiang MH, Kim YC, Oh YJ, Markelonis GJ, Oh TH. Minocycline alleviates death of oligodendrocytes by inhibiting pro-nerve growth factor production in microglia after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7751–7761. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1661-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price C, Makintubee S, Herndon W, Istre GR. Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury and acute hospitalization and rehabilitation charges for spinal cord injuries in Oklahoma, 1988-1990. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:37–47. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chhabra HS, Arora M. Demographic profile of traumatic spinal cord injuries admitted at Indian Spinal Injuries Centre with special emphasis on mode of injury: a retrospective study. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:745–754. doi: 10.1038/sc.2012.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang F, Li C, Gao C, Li Z, Yang J, Liu X, Wang Y. Effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on NACHT domain-leucine-rich-repeat- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 inflammasome expression in rats following spinal cord injury. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:4650–4656. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang SM, Wu R. The double danger of ethanol and hypoxia: their effects on a hepatoma cell line. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2009;2:182–189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim do R, Kim HY, Park JK, Park SK, Chang MS. Aconiti Lateralis Preparata Radix Activates the Proliferation of Mouse Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Induces Osteogenic Lineage Differentiation through the Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2/Smad-Dependent Runx2 Pathway. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:586741. doi: 10.1155/2013/586741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li F, Fei D, Sun L, Zhang S, Yuan Y, Zhang L, Zhao K, Li R, Yu Y. Neuroprotective effect of bone marrow stromal cell combination with atorvastatin in rat model of spinal cord injury. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:4967–4974. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu W, Ding Y, Zhang X, Wang L. Bone marrow stromal cells inhibit caspase-12 expression in rats with spinal cord injury. Exp Ther Med. 2013;6:671–674. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehrotra S, Pecaut MJ, Gridley DS. Minocycline modulates cytokine and gene expression profiles in the brain after whole-body exposure to radiation. In Vivo. 2014;28:21–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park SI, Park SK, Jang KS, Han YM, Kim CH, Oh SJ. Preischemic neuroprotective effect of minocycline and sodium ozagrel on transient cerebral ischemic rat model. Brain Res. 2015;1599:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hellal F, Hurtado A, Ruschel J, Flynn KC, Laskowski CJ, Umlauf M, Kapitein LC, Strikis D, Lemmon V, Bixby J, Hoogenraad CC, Bradke F. Microtubule stabilization reduces scarring and causes axon regeneration after spinal cord injury. Science. 2011;331:928–931. doi: 10.1126/science.1201148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koda M, Nishio Y, Kamada T, Someya Y, Okawa A, Mori C, Yoshinaga K, Okada S, Moriya H, Yamazaki M. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) mobilizes bone marrow-derived cells into injured spinal cord and promotes functional recovery after compression-induced spinal cord injury in mice. Brain Res. 2007;1149:223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravikumar R, Fugaccia I, Scheff SW, Geddes JW, Srinivasan C, Toborek M. Nicotine attenuates morphological deficits in a contusion model of spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:240–251. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stirling DP, Khodarahmi K, Liu J, McPhail LT, McBride CB, Steeves JD, Ramer MS, Tetzlaff W. Minocycline treatment reduces delayed oligodendrocyte death, attenuates axonal dieback, and improves functional outcome after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2182–2190. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5275-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chio CC, Lin JW, Chang MW, Wang CC, Kuo JR, Yang CZ, Chang CP. Therapeutic evaluation of etanercept in a model of traumatic brain injury. J Neurochem. 2010;115:921–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du M, Chen R, Quan R, Zhang L, Xu J, Yang Z, Yang D. A brief analysis of traditional chinese medical elongated needle therapy on acute spinal cord injury and its mechanism. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:828754. doi: 10.1155/2013/828754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crespo-Ruiz B, del-Ama AJ, Jimenez-Diaz FJ, Morgan J, de la Pena-Gonzalez A, Gil-Agudo AM. Physical activity and transcutaneous oxygen pressure in men with spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49:913–924. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2011.05.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Pan S, Yang X, Zhu B, Wang D. Oxidative phosphorylated neurofilament protein M protects spinal cord against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Neural Regen Res. 2014;9:1672–1677. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.141803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lukacova N, Davidova A, Kolesar D, Kolesarova M, Schreiberova A, Lackova M, Krizanova O, Marsala M, Marsala J. The effect of N-nitro-L-arginine and aminoguanidine treatment on changes in constitutive and inducible nitric oxide synthases in the spinal cord after sciatic nerve transection. Int J Mol Med. 2008;21:413–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X, Luo P, Wang Q, Xiong L. Electroacupuncture Pretreatment as a Novel Avenue to Protect Brain against Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:195397. doi: 10.1155/2012/195397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nandoe Tewarie RD, Hurtado A, Levi AD, Grotenhuis JA, Oudega M. Bone marrow stromal cells for repair of the spinal cord: towards clinical application. Cell Transplant. 2006;15:563–577. doi: 10.3727/000000006783981602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SM, Yune TY, Kim SJ, Park DW, Lee YK, Kim YC, Oh YJ, Markelonis GJ, Oh TH. Minocycline reduces cell death and improves functional recovery after traumatic spinal cord injury in the rat. J Neurotrauma. 2003;20:1017–1027. doi: 10.1089/089771503770195867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kluppel M. Efficient secretion of biologically active Chondroitinase ABC from mammalian cells in the absence of an N-terminal signal peptide. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;351:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0705-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, Chen C, Ma S, Wang Y, Zhang X, Su X. Inhibition of monocyte chemoattractant peptide-1 decreases secondary spinal cord injury. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:4262–4266. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H, Fang J, Su H, Yang M, Lai W, Mai Y, Wu Y. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells attenuate lung inflammation of hyperoxic newborn rats. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:589–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2012.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim HS, Suh YH. Minocycline and neurodegenerative diseases. Behav Brain Res. 2009;196:168–179. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Figley SA, Liu Y, Karadimas SK, Satkunendrarajah K, Fettes P, Spratt SK, Lee G, Ando D, Surosky R, Giedlin M, Fehlings MG. Delayed administration of a bio-engineered zinc-finger VEGF-A gene therapy is neuroprotective and attenuates allodynia following traumatic spinal cord injury. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogers RS, Graziottin TM, Lin CS, Kan YW, Lue TF. Intracavernosal vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injection and adeno-associated virus-mediated VEGF gene therapy prevent and reverse venogenic erectile dysfunction in rats. Int J Impot Res. 2003;15:26–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhong P, Liu Y, Hu Y, Wang T, Zhao YP, Liu QS. BDNF interacts with endocannabinoids to regulate cocaine-induced synaptic plasticity in mouse midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2015;35:4469–4481. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2924-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jakeman LB, Wei P, Guan Z, Stokes BT. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor stimulates hindlimb stepping and sprouting of cholinergic fibers after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 1998;154:170–184. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Houweling DA, van Asseldonk JT, Lankhorst AJ, Hamers FP, Martin D, Bar PR, Joosten EA. Local application of collagen containing brain-derived neurotrophic factor decreases the loss of function after spinal cord injury in the adult rat. Neurosci Lett. 1998;251:193–196. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00536-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamei N, Tanaka N, Oishi Y, Ishikawa M, Hamasaki T, Nishida K, Nakanishi K, Sakai N, Ochi M. Bone marrow stromal cells promoting corticospinal axon growth through the release of humoral factors in organotypic cocultures in neonatal rats. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:412–419. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.5.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Planchon SM, Wuerzberger-Davis SM, Pink JJ, Robertson KA, Bornmann WG, Boothman DA. Bcl-2 protects against beta-lapachone-mediated caspase 3 activation and apoptosis in human myeloid leukemia (HL-60) cells. Oncol Rep. 1999;6:485–492. doi: 10.3892/or.6.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bao F, Liu D. Peroxynitrite generated in the rat spinal cord induces apoptotic cell death and activates caspase-3. Neuroscience. 2003;116:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00571-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang Y, Gong FL, Zhao GB, Li J. Chrysin suppressed inflammatory responses and the inducible nitric oxide synthase pathway after spinal cord injury in rats. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:12270–12279. doi: 10.3390/ijms150712270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J, Li Y, Zheng X, Gao Q, Liu Z, Qu R, Borneman J, Elias SB, Chopp M. Bone marrow stromal cells protect oligodendrocytes from oxygen-glucose deprivation injury. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:1501–1510. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abcouwer SF, Lin CM, Shanmugam S, Muthusamy A, Barber AJ, Antonetti DA. Minocycline prevents retinal inflammation and vascular permeability following ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:149. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tokmakov AA, Sato K, Konaka K, Fukami Y. Inhibition of MAPK pathway by a synthetic peptide corresponding to the activation segment of MAPK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;252:214–219. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buchwalter A, Van Dort C, Schultz S, Smith R, Le IP, Abbott JL, Oosterhouse E, Johnson AE, Hansen-Smith F, Burnatowska-Hledin M. Expression of VACM-1/cul5 mutant in endothelial cells induces MAPK phosphorylation and maspin degradation and converts cells to the angiogenic phenotype. Microvasc Res. 2008;75:155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu Z, Wang BR, Wang X, Kuang F, Duan XL, Jiao XY, Ju G. ERK1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediate iNOS-induced spinal neuron degeneration after acute traumatic spinal cord injury. Life Sci. 2006;79:1895–1905. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xia Y, Chen BY, Sun XL, Duan L, Gao GD, Wang JJ, Yung KK, Chen LW. Presence of proNGF-sortilin signaling complex in nigral dopamine neurons and its variation in relation to aging, lactacystin and 6-OHDA insults. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:14085–14104. doi: 10.3390/ijms140714085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J, Brodie C, Li Y, Zheng X, Roberts C, Lu M, Gao Q, Borneman J, Savant-Bhonsale S, Elias SB, Chopp M. Bone marrow stromal cell therapy reduces proNGF and p75 expression in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;279:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cirillo G, Colangelo AM, Bianco MR, Cavaliere C, Zaccaro L, Sarmientos P, Alberghina L, Papa M. BB14, a Nerve Growth Factor (NGF)-like peptide shown to be effective in reducing reactive astrogliosis and restoring synaptic homeostasis in a rat model of peripheral nerve injury. Biotechnol Adv. 2012;30:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang XP, Li Y, Wang Y, Wang Y, Wang P. beta-Tryptase up-regulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression via proteinase-activated receptor-2 and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in bone marrow stromal cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:1550–1558. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2010.496013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang YT, Lu XM, Zhu F, Huang P, Yu Y, Long ZY, Wu YM. Ameliorative Effects of p75NTR-ED-Fc on Axonal Regeneration and Functional Recovery in Spinal Cord-Injured Rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;52:1821–34. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8972-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nadeau JR, Wilson-Gerwing TD, Verge VM. Induction of a reactive state in perineuronal satellite glial cells akin to that produced by nerve injury is linked to the level of p75NTR expression in adult sensory neurons. Glia. 2014;62:763–777. doi: 10.1002/glia.22640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tom VJ, Sandrow-Feinberg HR, Miller K, Domitrovich C, Bouyer J, Zhukareva V, Klaw MC, Lemay MA, Houle JD. Exogenous BDNF enhances the integration of chronically injured axons that regenerate through a peripheral nerve grafted into a chondroitinase-treated spinal cord injury site. Exp Neurol. 2013;239:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wei WJ, Yu ZY, Yang HJ, Xie MJ, Wang W, Luo X. Cellular expression profile of RhoA in rats with spinal cord injury. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2014;34:657–662. doi: 10.1007/s11596-014-1333-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharp KG, Yee KM, Stiles TL, Aguilar RM, Steward O. A re-assessment of the effects of treatment with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (ibuprofen) on promoting axon regeneration via RhoA inhibition after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2013;248:321–337. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edalat H, Hajebrahimi Z, Movahedin M, Tavallaei M, Amiri S, Mowla SJ. p75NTR suppression in rat bone marrow stromal stem cells significantly reduced their rate of apoptosis during neural differentiation. Neurosci Lett. 2011;498:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]