Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to develop a novel release system for grafted islets. Materials and methods: A graphene oxide-FTY720 release system was constructed to test the drug loading and releasing capacity. The recipient rats were divided into four groups as following: Experiment group A (EG A) and B (EG B); Control group A (CG A) and B (CG B). In each group, (2000±100) IEQ microencapsulated islets were implanted into the abdominal cavity of the recipients with oral FTY720, local graphene oxide-FTY720 injection, without immunosuppressants, and with graphene oxide-saturated solution respectively. We detected the immunological data, the blood glucose level, and pericapsular overgrowth to show the transplantation effect. Results: 31% of adsorptive FTY720 was released within 6 h, and 82% of FTY720 was released within 48 h. From day 5 to 8, the amount of PBL in EG B was significantly less than those in EG A (P<0.01). The CD3+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes were suppressed 3 days longer in EG B than in EG A. On day 19 posttransplantation, the blood glucose level in EG B was much lower than that in EG A (P<0.01). On the same day, pericapsular overgrowth was grade I in EG B, grade II in other groups. Conclusions: Graphene oxide-FTY720 complex showed a drug releasing effect. Local application of graphene-FTY720 releasing system could decrease the amount of peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) and the percentage of CD3 and CD8 T lymphocytes in blood for longer time than oral drug application. This releasing system could achieve a better blood glucose control.

Keywords: Islet transplantation, microencapsulation, graphene oxide, overgrowth, immunosuppressants

Introduction

Lim first used alginate polylysine to encapsulate islet cells and successfully transplanted them into rats with diabetes [1]. From then on, great progress has been made in islet transplantation. In 2008, the Collaborative Islet Transplant Registry (CITR) reported that among 325 patients who received 649 islet transplantations from 712 donors, only 23% of them remained free from insulin injection 3 years after the first transplantation [2]. The application of islet transplantation is limited by the shortage of donors, immune rejection, high costs, and serious side effects associated with long-term administration of immunosuppressants.

In order to overcome immune rejection, microencapsulation was introduced to protect the transplants from immunological rejection [3]. However, microcapsules could not provide a perfect immunoisolation for the grafts and pericapsular overgrowth would lead to a function loss of the transplanted islets [4,5]. So immunosuppressants were still administered to inhibit immunological rejection [6].

FTY720, as a novel immunosuppressant, could significantly prolong the survival of the grafts, reduce the side effects of immunosuppressants, reverse immunulogical rejection, and was nontoxic to grafted islets [7-10]. When FTY720 was administered in normal rats at an oral dose of 0.1-10 mg/kg, the peripheral blood lymphocytes reduced apparently within 3 hours and recovered to normal level within 1 to 2 weeks [11]. FTY720 local administration also had better water-solubility and fat-solubility, higher bioavailability, and higher drug concentration in grafts and lymph nodes than in blood [12].

There were still problems involved in the use of FTY720, such as the large dosage administration, the apparent side effects on the whole body, and the availability of low concentration of drugs at the target organs [13-15].

Therefore, local immunosuppressant releasing system had been reported to show good effect [16-20]. Graphene oxide was a single-atomic-layered material made from nature graphite crystals [21,22], which could be used in medicine as a drug carrier because of its superior drug loading capacity and excellent biocompatibility [23-26]. In this study, we chose microencapsulated islets mixed with graphene oxide-FTY720 to inject into abdominal cavity of the recipients, and attempted to create a local immunosuppression microenvironment by taking the advantage of the drug releasing system.

In summary, we aimed to design graphene oxide-immunosuppressant complex as a new immunosuppressive releasing system around the grafted islets to achieve a better local immunosuppression after transplantation.

Materials and methods

Animals

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Clinical Hospital attached to the Harbin Medical University. 80 specific-pathogen-free (SPF) male Sprague Dawley rats (10 to 12 weeks old and 200-300g in weight) were chosen as donors; 32 SPF male Wistar rats (7 to 8 weeks old and 150-200 in weight) were chosen as recipients. Animals were provided by Experimental Animal Center of the First Clinical Hospital. The rats were placed in 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle and fed with standard laboratory food (PMI feed) and water ad libitum.

Reagents

Dulbecco’s modification of Eagle’s medium (DMEM), Rosewell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 culture medium, fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin were purchased from Invitrogen (Burlington, Canada); Ham’s F12 nutrient medium (HAM-F12), Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS), Ethylene Diamine Tetra-acetic Acid (EDTA), and collagenase were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, United States of America); Streptozotocin was purchased from Upjohn, Kalamazoo (MI, USA); Dithizone (DTZ), Ficoll 400, green fluorescent dye SYTO, ethidium bromide (EB) and rat insulin radioimmunoassay kits were purchased from LINCO (St. Charles, MO, USA); 2.2% high purity low viscosity high-guluronic acid (LVG) alginate (Pronova) was obtained from FMC Biopolymer (Drammen, Norway); Fluorescscein Isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-rat CD3, PE anti-rat CD8 were purchased from BioLegend (California, USA); and FTY720 standard product was from Cayman (Ann Arbor, USA).

Preparation of grapheme oxide saturated solution

Graphene oxide (the average diameter of one layer of graphene was 200 µm, its thickness was equal to one carbon atom, total 40 mg graphene provided from Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China) was put into 200 ml deionized water, dispersed uniformly, and then put into 500 W ultrasonator for 30 min. The harvested graphene oxide suspension was centrifuged at 60 rpm for 15 min, and the supernatant (graphene oxide saturated solution) was isolated, kept sealed in plastic tubes, and then stored for later use.

Drug loading test

Different doses of FTY720 (1 mg, 3 mg, 5 mg, and 7 mg) were added into 50 ml graphene oxide saturated solution. After 24 h, the solution was centrifuged at 10000 rpm, and the supernatant was harvested for absorbance test. According to Lambert-Beer’s Law, A (absorbance)=k·cl, where k is constant of proportionality, c is concentration of light absorbing materials, and l is transparent liquid layer thickness. At the maximum absorption wavelength of 220 nm, the absorbance of different samples was obtained, and the maximum FTY720 absorption dosage was identified according to drug concentration-absorbance standard curve.

Drug releasing capacity test

A 50 ml graphene oxide-FTY720 solution (FTY720 reached maximum absorption dosage) was prepared and added into 50 ml deionized water to test the drug release. 2 ml was taken to test the absorbance every 6 h, and 2 ml deionized water was added to keep the volume. Above experiment was repeated five times, the mean value was calculated, and the drug releasing rate-time curve was obtained.

Establishment of type I diabetic rat models

The diabetic model used in this study had been described previously [27]: SD rats were fasted overnight and given a single injection of streptozotocin (90 mg/kg) from day 10 to day 14 before transplantation. After 48 h, blood glucose was measured by using a One Touch system (Johnson & Johnson, USA). Rats which had non-fasting blood glucose levels higher than 20 mmol/L on two separate occasions were identified as a successful model. Blood was collected through tail vein for biochemical analysis.

Rat islet isolation and microencapsulation

Rat bile duct cannula perfusion was conducted with 20 mL Cold HBSS containing 1.5 mg/mL collagenase V. Digestion of the islets was carried out at 37°C, and the cells were purified with Ficoll density gradient solution at 4°C, as described previously [28,29]. Rat pancreatic islets were collected and counted. Islet equivalents (IEQ) were calculated as (Σ islet number in each diameter × corresponding coefficient) × dilution factor [30].

Islet microencapsulation was undertaken as described previously [31-33]. Briefly, the cell pellets were mixed with 2.2% alginate (Pronova, Norway) in a ratio of 1:6 (v/v) and then placed in electrostatic droplet generator (Serial No. LS-01.005, Dottikon, Switzerland). The encapsulated islets were then collected into a petri dish containing 1.1% barium chloride solution and washed with saline. The cells were resuspended in 15 mL RPMI1640 (containing 10% Fetal Bovine Serum, penicillin, and streptomycin) and subsequently stained with DTZ and green fluorescent dye (SYTO/EB). The microencapsulated rat pancreatic islets were cultured in HAM-F12 medium at 37°C in a 5% carbon dioxide (CO2) incubator.

Islet identification and activity detection

Islet activity was estimated by SYTO green and EB staining and observed under fluorescence microscopy (BX51TF, Tokyo, Japan). Islets with more than 50% stained cells were defined as living islets and expressed as a percentage of total islet number in each group [34].

Aliquots of 25 islet equivalents were washed with glucose-free medium prior to static glucose challenge. The islets were incubated in low (2.8 mM) or high (20 mM) glucose concentration medium at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 30 min. Supernatant samples were collected, and insulin concentrations were measured using a rat/mouse insulin enzyme-linked immnosorbent assay kit (Linco, MO). Insulin sensitivity index (ISI) was calculated as the ratio of the insulin concentration in high-glucose solution to the concentration in low-glucose solution [35].

Experiment groups

Diabetic rats were anesthetized by 7% chloral hydrate injection into abdominal cavity with 0.5 mL/100 g weight. Microencapsulated islets were added into 2 ml graphen oxide solution or graphen oxide-FTY720 solution, and injected into the abdominal cavity of the recipients through a small cut on the abdominal wall. All recipients were divided into the following four groups:

Experiment group A (EG A): (2000±100) IEQ microencapsulated islets were implanted into abdominal cavity (n=8) and 0.087 mg FTY720 was administrated orally. The dosage of FTY720 (0.5 mg/kg·d) was enough to reach the blood concentration of maintaining whole body immunosuppression [14].

Experiment group B (EG B): (2000±100) IEQ microencapsulated islets were implanted into abdominal cavity (n=8) with graphene oxide-FTY720 solution (0.087 mg FTY720/0.2 mg graphene oxide/ml) locally through abdominal cavity injection. The dosage of FTY720 in this group was equal to that in EG A.

Control group A (CG A): (2000±100) IEQ microencapsulated islets were implanted into abdominal cavity (n=8) without immunosuppressants.

Control group B (CG B): (2000±100) IEQ microencapsulated islets were implanted into abdominal cavity (n=8) with 2 ml graphene oxide saturated solution administered through local abdominal cavity injection.

Peripheral blood lymphocyte count

Blood samples from the recipients were collected through caudal vein at the following time points: 0 h (before transplantation), 4 h, 8 h, and 24 h, followed by day 2, 5, 8, and 12 after transplantation [15], then diluted in 5 µl of 1.5% acetic acid solution, and the amount of leucocytes were counted. Another 2-3 µl vein blood was obtained for smear test after Wright’s staining, which was observed under high power lens. About 400 leucocytes were collected, and the percentage of lymphocytes was counted.

Analysis on T lymphocyte subsets

Caudal vein blood (50 µl) was added with 15 µl fluorescent antibody (anti-CD3-FITC and anti-CD8-PE), incubated for 30 min, then added 1 ml red blood cell lysis solution, centrifuged for 15 min. The supernatant was discarded. The precipitate was washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Cells were detected by flow cytometry (FACtarplus, BD Company, USA).

Blood glucose detection

Rat blood glucose was taken before transplantation and at day 5 (first week), 12 (second week), 19 (third week), and 33 (fourth week) after transplantation. Rats which showed non-fasting blood glucose levels higher than 20 mmol/L on two separate occasions, less movement, and constant weight loss were identified with functional loss of the grafts.

Evaluation of pericapsular overgrowth

Two rats in each group were euthanatized every week. The abdominal cavity was cut open and the accumulation of graphene oxide and pericapsular overgrowth were observed. Adhesive microcapsules were separated and counted, and the ratio of overgrown microcapsules to every 100 retrieved microcapsules was calculated. The severity of overgrowth was assessed as Grade 0: more than 75% of microcapsules had no surface adhesion; Grade I: more than 75% of the microcapsules surface had less than 25% surface adhesion; Grade II: more than 75% of microcapsule surfaces showed 25-50% surface area adhesion; and Grade III: more than 75% of the microcapsules surface had more than 50% surface area adhesion [36].

Immunohistochemistry analysis

The parafin sections of microencapsulated grafts were processed as following: dewaxing, hydration, PBS washing, antigen retrieval, 3% hydrogen peroxide sealing for 20 min, 5% normal goat serum sealing, first antibody (rabbit anti-rat CD3) incubation, rewarming, second antibody incubation (goat anti-rabbit antibody with biotin labeling), diaminobenzidine staining, toasting at 60°C for 2 h, hematoxylin staining, and dehydration. The pericapsular overgrowth was then observed under microscope. The yellow staining CD3 T lymphocytes in each high magnification around the capsule were counted and compared in each group to evaluate the grade of pericapsular overgrowth.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., USA). Data were expressed as means ± standard deviations. One-way analysis of variance with Student-Newman-Keuls test for post hoc analysis was used for comparisons of between groups. Two samples from in vitro culture or in vivo transplant were compared using t-tests. Values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Drug loading and releasing of graphene oxide

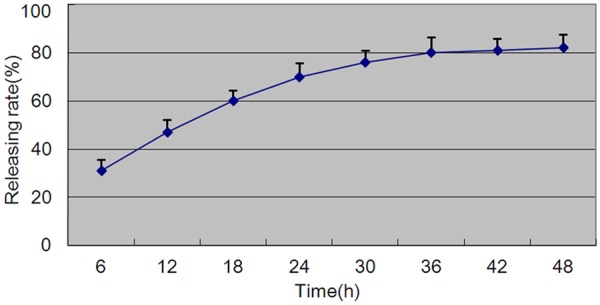

The concentration of graphene oxide saturated solution was 0.2 mg/ml according to the drug concentration-absorbance standard curve. About 1 ml graphene oxide saturated solution was loaded with FTY720 0.087 mg. FTY720 releasing rate changing with time in graphene oxide-FTY720 complex was shown (Figure 1). There was burst release in the initial stage. 31% of adsorptive FTY720 was released within 6 h, and the drug releasing rate slowed down between 6 h and 30 h. After 36 h, a balance was reached by drug adsorption and release. After 48 h, 82% of FTY720 was released.

Figure 1.

FTY720 release changing with time. Experiments performed five times.

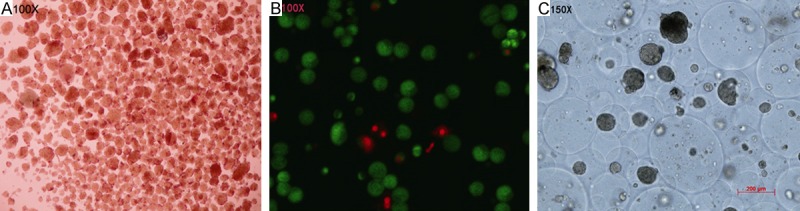

Activity detection of microencapsulated islets

Observation under inverted microscope showed that islets were transparent or semitransparent and stained with orange red. They were round and oval shape in varied size (50-350 µm in diameter). Under fluorescence microscope, the live islets were stained green, and dead islets were stained red. The survival rate of islets reached 90%. The average ISI value was 4.87±0.33. Average 1-3 islets were encapsulated in one capsule. The diameter of capsules varied from 100 µm to 500 µm (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Activity detection of microencapsulated islets. A. DTZ stain of islets (100×). B. SYTO-green and EB stain of islets (100×). C. Microencapsulated islets (150×). A. The red stain represented the islets; B. The green stain represented live islets, red stain represented dead islets; C. 1-3 islets were encapsulated in one capsule.

Immunological changes in recipients after islet transplantation

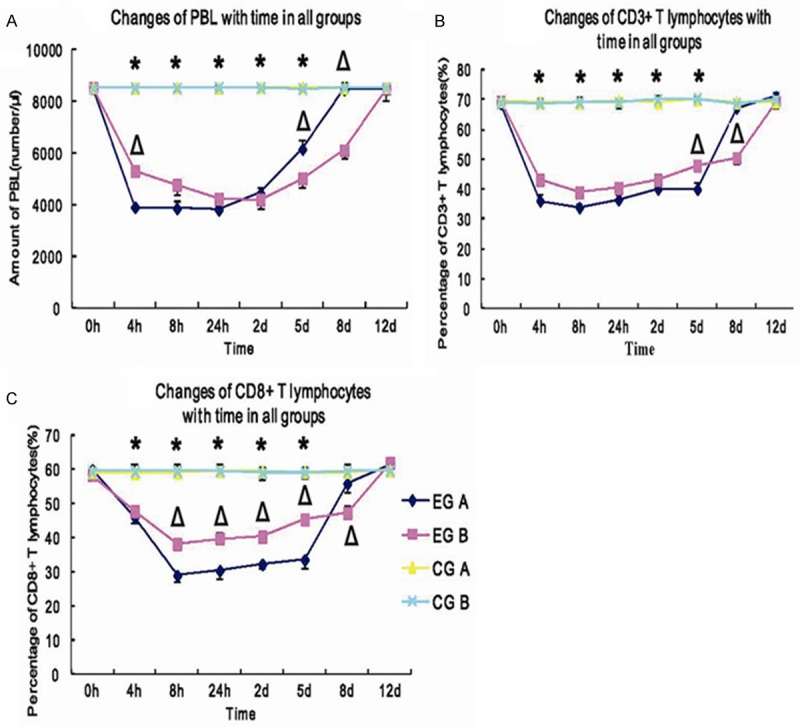

Changes of peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) after transplantation were shown (Figure 3A). In EG A, the amount of PBL decreased rapidly after transplantation and reached the lowest value (3914±297/μl) at 4 h after transplantation. Then the amount of PBL increased slowly to day 2, increased rapidly 2 days later, and then recovered to the pretransplantation level (8465±166/μl) on day 8. In EG B, the amount of PBL decreased rapidly after transplantation, reached (5039±368/μl) at 4 h, and decreased further. The lowest value reached 4215±339/μl. The amount of PBL increased on day 2 after transplantation and recovered to the pretransplantation level on day 12. From 4 to 24 h, the amount of PBL in EG B was significantly more than those in EG A (P<0.01). From day 5 to 8, the amount of PBL in EG B was significantly less than those in EG A (P<0.01). From 4 h to day 5, the amount of PBL in EG B was significantly less than in CG B (P<0.01).

Figure 3.

A: ΔP<0.01 EG B vs. EG A; *P<0.01 EG B vs. CG B; B: ΔP<0.01 EG B vs. EG A; *P<0.01 EG B vs. CG B; C: ΔP<0.05 EG B vs. EG A; *P<0.01 EG B vs. CG B.

The percentage of CD3+ T lymphocyte subsets in EG A decreased rapidly within 4 h posttransplantation and reached 36.1 (±1.24)%. It increased rapidly on day 5 and recovered to the pretransplantation level on day 12. The percentage of CD3+ T lymphocyte subsets in EG B decreased rapidly within 4 h posttransplantation and reached 43.2 (±1.66)%. It then reached the lowest value at 8 h, then increased slowly within 8 h to day 8, increased rapidly after day 8, and recovered to the pretransplantation level on day 12. The percentage of CD3+ T lymphocyte subsets in EG A was significantly lower than in EG B within 4 h to day 5 posttransplantation (P<0.01), and significantly higher than in EG B on day 8 (P<0.01). There were significant difference between EGs and CGs within 4 h to day 5 post-transplantation (P<0.01) (Figure 3B).

The percentage of CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets in EG A decreased rapidly after transplantation and reached the lowest value of 29 (±1.71)% at 8 h, and it was maintained a stable level from 8 h to day 5, then increased rapidly after day 5, and recovered to the pretranplantation level on day 12. The percentage of CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets in EG B decreased rapidly and reached the lowest value of 38.2 (±2.21)% at 8 h. This value was significantly higher than that in EG A (P<0.01). The percentage of CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets in EG B was significantly higher than that in EG A from 8 h to day 5 (P<0.05) and significantly lower than that in EG A on day 8 (P<0.01). There were significant difference between EG B and CG B from 4 h to day 5 after transplantation (P<0.01). There were no significant differences observed between pre- and post-transplantation in CGs (P>0.05) (Figure 3C).

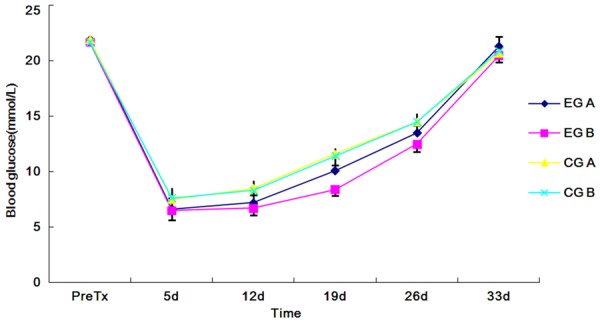

Changes in blood glucose of recipients after transplantation

The blood glucose in all groups decreased to normal level within 5 days posttransplantation and maintained a normal level to day 12. After that, the blood glucose in all groups increased gradually, which rised much slower in EG B than in other groups. On day 19 posttransplantation, the blood glucose value differed significantly in EG B (P<0.01) and insignificantly in EG A (P>0.05), compared to those in CGs. And the difference was significant between EG A and EG B (P<0.01). On day 33 posttransplantation, the blood glucose in all groups recovered to their pretransplantation levels (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Changes in blood glucose of recipients after transplantation, ΔP<0.01 EG B vs. EG A.; *P<0.01 EG B vs. CG B.

Pericapsular overgrowth after transplantation

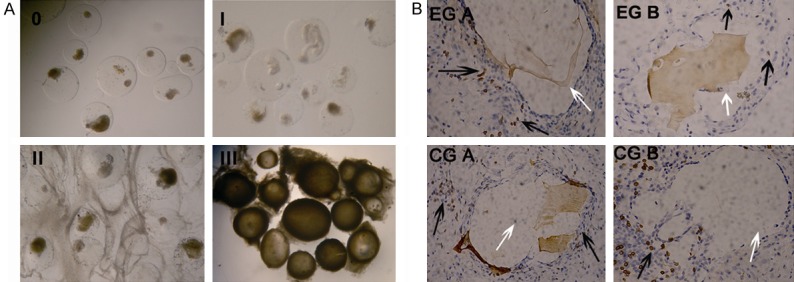

Pericapsular overgrowth was divided into grade 0 to III under light microscope (Figure 5A). The changes of pericapsular overgrowth (0-III grade) with time in all groups were shown (Table 1). The grade of pericapsular overgrowth in EG A and CGs were the same at each time point. But on day 19 (third week) posttransplantation, compared to grade I overgrowth in EG B, grade II overgrowth was seen in other groups.

Figure 5.

A. Grade of overgrowth, from 0-III grade under light microscope (150×). B. Comparison of the pericapsular overgrowth in both EGs on day 19 posttransplantation (400×). (In each group, two recipients were analyzed) the black arrows represent the yellow stained T lymphocytes, and the white arrows represent the capsules.

Table 1.

Changes of pericapsular overgrowth (0-III grade) with time in all groups

| Groups\Time | d 12 | d 19 | d 26 | d 33 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EG A | 1 | I | II | II | III |

| 2 | I | II | II | III | |

| EG B | 1 | I | I | II | III |

| 2 | I | I | II | III | |

| CG A | 1 | I | II | II | III |

| 2 | I | II | II | III | |

| CG B | 1 | I | II | II | III |

| 2 | I | II | II | III | |

Comparison of the pericapsular overgrowth in all groups on day 19 posttransplantation was shown. The yellow staining cells were less than 10 in EG B under each high magnification, while they were more than 30 in EG A and CGs (Figure 5B).

Discussion

The clinical application of microencapsulated islet transplantation was limited by functional loss of grafted islets, immunoisolation imperfection of the microcapsules, and oxygen and nutrients insufficiency of the encapsulated islets caused by pericapsular overgrowth [37]. Although the administration of immunosuppressants could solve these complications to some extent, it brought problems such as apparent side effects, and imperfection of immunological suppression [7,8]. Therefore, local immunological suppression therapy was considered as a good option. It provided the advantage of taking direct effect of immunosuppressant on grafts to inhibit immune rejection. To avoid damages of the grafts, sensitized T lymphocytes and immune rejection could be inhibited by injecting immunosuppressants around the grafts [38-40].

While local administration of immunosuppressants through sustained drug releasing system could prolong the effect of immunosuppressants. Graphene oxide had a high specific surface area, and its drug loading capacity was as high as 238% and superior to other drug carriers [41]. In the present study, the drug loading rate of graphene oxide was 43.5% and drug releasing rate reached 31% at 6 h, and reached 82% at 48 h.

CD3 was a specific molecular marker on the surface of T lymphocytes and CD3 positive lymphocytes were frequently detected in allografts. For the islet allo-transplantation, CD3 and CD8 molecular markers were chosen to response the effect of FTY720 on peripheral blood lymphocytes in the recipients. The results showed that systemic (oral) drug administration showed good effect to inhibit the homing of peripheral blood lymphocytes, while abdominally local drug administration took a better effect. It was proved to inhibit lymphocyte homing for longer time with the continuous release of the immunosuppressants. In Figure 3, the amount of PBL in EG A was inhibited to the lowest value within 24 hs and recovered to pretransplantation level on day 8. While in EG B, PBL was inhibited to the lowest value on day 2 and recovered to pretransplantation level on day 12. This proved that local drug releasing system application had a longer time inhibition on PBL than FTY720 oral administration.

Notably, in Figure 3B and 3C, the percentage of CD3+ T lymphocyte subsets in EGs was inhibited to the lowest level within 4 hs, while the percentage of CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets in EGs was inhibited to the lowest level within 8hs. This proved that CD3+ T lymphocyte subsets were more sensitve to FTY720 than CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets. The CD3+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes were suppressed 3 days longer in EG B than in EG A. This further proved that the local administration of immunosuppressant releasing system produced an inhibiting effect for longer time.

In Figure 4, the blood glucose in EG B increased much slower than in other groups. On day 19 posttransplantation, there was significant difference between the blood glucose of EG A and EG B (P<0.01). Although the blood glucose value in all groups rised back to pretransplantation level on day 33, we found that with administration of the same dose of FTY720 through diffirent ways, EG B showed a better blood glucose control than EG A and CGs on day 19. This indicated that the local use of graphene oxide-FTY720 release system could apparently inhibit immune rejection around the grafted islets and kept most islets survival and normal function on day 19. Because we only tested the effect of FTY720 administration one time, we loaded the same dose of FTY720 with graphene oxide to the oral FTY720. So the loading dose was far less than the saturated dose in grapheme oxide. If we loaded enough dose of FTY720 with graphene oxide, the releasing time and blood control would be much better.

In Figure 5, on day 19 posttransplantation, compared to the grade II overgrowth in EG A and CGs, only grade I overgrowth was seen in EG B. The yellow stained CD3+ T lymphocytes were fewer than 10 under one high magnification in EG B, but were more than 30 in EG A and CGs. We also observed that once oral FTY720 administration could not show apparent effect on inhibiting CD3+ aggregation around the microencapsulated islets because of its rapid reduce in blood concentration. Although local administration of grapheme oxide-FTY720 releasing system couldn’t keep the blood concentration as high as oral FTY720, it could keep a continuous drug release for longer time. These data proved that local FTY720 releasing system could inhibit the aggregation of T lymphocytes around the microcapsules and reduce the pericapsular overgrowth grade for longer time.

In conclusion, graphene oxide-FTY720 complex showed a drug releasing effect. Local application of graphene-FTY720 releasing system could decrease the amount of PBL, and the percentage of CD3 and CD8 T lymphocytes in blood for longer time than oral drug application. This releasing system was also proved to reduce the aggregation of T lymphocytes around the microcapsules and reduce the pericapsular overgrowth. So we could make a better blood glucose control through reducing the damage of grafted islets via inhibiting PBL, CD3 and CD8 T lymphocytes in blood and the pericapsular overgrowth. However, some limitations of graphene oxide drug loading system were also observed in our study: the tardiness in vivo clearance of graphene oxide and the initial drug burst release phenomenon. Further studies are needed to optimize the grapheme oxide-FTY720 release system to improve the islet transplantation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Natural Science Fund of Heilongjiang Province (D201051) and a grant from Applicable Technique Research and Development fund of Harbin city (2013RFQYJ158).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Lim F, Sun AM. Microencapsulated islets as bioartificial endocrine pancreas. Science. 1980;210:908–910. doi: 10.1126/science.6776628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alejandro R, Barton FB, Hering BJ, Wease S Collaborative Islet Transplant Registry Investigators. 2008 Update from the Collaborative Islet Transplant Registry. Transplantation. 2008;86:1783–8. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181913f6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kobayashi T, Arefanian H, Harb G, Tredget EB, Rajotte RV, Korbutt GS, Rayat GR. Prolonged survival of microencapsulated neonatal porcine islet xenografts in immune-competent mice without antirejection therapy. Cell Transplant. 2008;17:1243–1256. doi: 10.3727/096368908787236602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Figliuzzi M, Plati T, Cornolti R, Adobati F, Fagiani A, Rossi L, Remuzzi G, Remuzzi A. Biocompatibility and function of microencapsulated pancreatic islets. Acta Biomater. 2006;2:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orive G, Tam SK, Pedraz JL, Halle JP. Biocompatibility of alginate-poly-L-lysine microcapsules for cell therapy. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3691–3700. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeong JH, Yook S, Hwang JW, Jung MJ, Moon HT, Lee DY, Byun Y. Synergistic effect of surface modification with poly(ethylene glycol) and immunosuppressants on repetitive pancreatic islet transplantation into antecedently sensitized rat. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:585–590. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu F, Hu S, Deleo J, Li S, Hopf C, Hoover J, Wang S, Brinkmann V, Lake P, Shi VC. Long-term islet graft survival in streptozotocin- and autoimmune-induced diabetes models by immunosuppressive and potential insulinotropic agent FTY720. Transplantation. 2002;73:1425–1430. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200205150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Truong W, Emamaullee JA, Merani S, Anderson CC, James Shapiro AM. Human islet function is not impaired by the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator FTY720. Am J Transplant. 2007;17:2031–2038. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinschewer DD, Ochsenbein AF, Odermatt B, Brinkmann V, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. FTY720 immunosuppression impairs effector T cell peripheral homing without affecting induction, expansion, and memory. J Immun. 2000;164:5761–5770. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu L, Wang C, He X, Shang W, Bi Y, Wang D. Long-term effect of FTY720 on lymphocyte count and islet allograft survival in mice. Microsurgery. 2007;27:300–304. doi: 10.1002/micr.20360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki S, Enosawa S, Kakefuda T, Shinomiya T, Amari M, Naoe S, Hoshino Y, Chiba K. A novel immunosuppressant, FTY720, with a unique mechanism of action, induces long-term graft acceptance in rat and dog allotransplantation. Transplantation. 1996;61:200–205. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199601270-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aki FT, Kahan BD. FTY720: A new kid on the block for transplant immunosuppression. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2003;3:665–681. doi: 10.1517/14712598.3.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor SR, Isa H, Joshi L, Lightman S. New developments in corticosteroid therapy for uveitis, Ophthalmologica. Ophthalmologica. 2010;1:46–53. doi: 10.1159/000318021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinto E, Zhang B, Song S, Bodor N, Buchwald P, Hochhaus G. Feasibility of localized immunosuppression: PLA microspheres for the sustained local delivery of a soft immunosuppressant. Pharmazie. 2010;65:429–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takita M, Matsumoto S, Noguchi H, Shimoda M, Ikemoto T, Chujo D, Tamura Y, Olsen GS, Naziruddin B, Purcell K, Onaca N, Levy MF. Adverse events in clinical islet transplantation: one institutional experience. Cell Transplant. 2012;21:547–551. doi: 10.3727/096368911X605466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eichenfield LF, Lucky AW, Boguniewicz M, Langley RG, Cherill R, Marshall K, Bush C, Graeber M. Safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus cream 1% in the treatment of mild and moderate atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:495–504. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.122187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reitamo S, Van Leent EJ, Ho V, Harper J, Ruzicka T, Kalimo K, Cambazard F, Rustin M, Taieb A, Gratton D, Sauder D, Sharpe G, Smith C, Junger M, de Prost Y. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment compared with that of hydrocortisone acetate ointment in children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:539–546. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.121831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo S, Han Y, Zhang X, Lu B, Yi C, Zhang H, Ma X, Wang D, Yang L, Fan X, Liu Y, Lu K, Li H. Human facial allotransplantation: a 2-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;372:631–638. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madani H, Hettiaratchy S, Clarke A, Butler PE. Immunosuppression in an emerging field of plastic reconstructive surgery: composite tissue allotransplantation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:245–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Sabrout R, Delaney V, Qadir M, Butt F, Hanson P, Butt KM. Sirolimus in combination with tacrolimus or mycophenolate mofetil for minimizing acute rejection risk in renal transplant recipients--a single center experience. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:89–94. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(03)00220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geim AK, Novoselov KS. The rise of graphene. Nat Mater. 2007;6:183–191. doi: 10.1038/nmat1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novoselov KS, Jiang D, Schedin F, Booth TJ, Khotkevich VV, Morozov SV, Geim AK. Two-dimensional atomic crystals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10451–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502848102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, Xia J, Zhao Q, Liu L, Zhang Z. Functional graphene oxide as a nanocarrier for controlled loading and targeted delivery of mixed anticancer drugs. Small. 2010;6:537–544. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang K, Gong H, Shi X, Wan J, Zhang Y, Liu Z. In vivo biodistribution and toxicology of functionalized nano-graphene oxide in mice after oral and intraperitoneal administration. Biomaterials. 2013;34:2787–2795. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ni G, Wang Y, Wu X, Wang X, Chen S, Liu X. Graphene oxide absorbed anti-IL10R antibodies enhance LPS induced immune responses in vitro and in vivo. Immunol Lett. 2012;148:126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang H, Wang XM, Wang CS. Research progress of graphene-based materials in the application to biomedicine. Acta Pharma Sin. 2012;47:291–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omer A, Duvivier-Kali V, Fernandes J, Tchipashvili V, Colton CK, Weir GC. Long-term normoglycemia in rats receiving transplants with encapsulated islets. Transplantation. 2005;79:52–58. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000149340.37865.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Y, Fu H, Wang Z, Zhou X, Xu Y, Wang D, Xue S, Li X. Improved methods of isolation and purification of rat islets and its viability research. Chin J Repar Recon Surg. 2010;24:406–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Dowd JF. The isolation and purification of rodent pancreatic islets of Langerhans. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;560:37–42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-448-3_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cardona K, Korbutt GS, Milas Z, Lyon J, Cano J, Jiang W, Bello-Laborn H, Hacquoil B, Strobert E, Gangappa S, Weber CJ, Pearson TC, Rajotte RV, Larsen CP. Long-term survival of neonatal porcine islets in nonhuman primates by targeting costimulation pathways. Nat Med. 2006;12:304–306. doi: 10.1038/nm1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolters GH, Fritschy WM, Gerrits D, van Schilfgaarde R. A versatile alginate droplet generator applicable for microencapsulation of pancreatic islets. J Appl Biomater. 1991;3:281–286. doi: 10.1002/jab.770030407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duvivier-Kali VF, Omer A, Parent RJ, O’Neil JJ, Weir GC. Complete protection of islets against allorejection and autoimmunity by a simple barium-alginate membrane. Diabetes. 2001;50:1698–1705. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fritschy WM, Wolters GH, van Schilfgaarde R. Effect of alginate-polylysine-alginate microencapsulation on in vitro insulin release from rat pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 1991;40:37–43. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bretzel RG, Alejandro R, Hering BJ, van Suylichem PT, Ricordi C. Clinical islet transplantation: guidelines for islet quality control. Transplant Proc. 1994;26:388–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiesli P, Schaffler E, Seifert B, Schmid C, Donath MY. Islets secretory capacity determines glucose homoeostasis in the face of insulin resistance. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2004;134:559–564. doi: 10.4414/smw.2004.10688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ren M, Liu R, Lv B, Gao Q, Feng J, Wu Y, Zhao Z, Zhou Y. Safety and efficacy of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid for removing microcapsules. J Surg Res. 2013;183:442–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Groot M, Schuurs TA, van Schilfgaarde R. Causes of limited survival of microencapsulated pancreatic islet grafts. J Surg Res. 2004;121:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stremmel C, Sienel W, Eggeling S, Passlick B, Slavin A. Inhibition of T cell homing by down-regulation of CD62L and the induction of a Th-2 response as a method to prevent acute allograft rejection in mice. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30:362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vagesjo E, Christoffersson G, Walden TB, Carlsson PO, Essand M, Korsgren O, Phillipson M. Immunological shielding by induced recruitment of regulatory T lymphocytes delays rejection of islets transplanted to muscle. Cell Transplant. 2014;43:189–196. doi: 10.3727/096368914X678535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagahara Y, Ikekita M, Shinomiya T. T cell selective apoptosis by a novel immunosuppressant, FTY720, is closely regulated with Bcl-2. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;137:953–962. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang Y, Zhang YM, Chen Y, Zhao D, Chen JT, Liu Y. Construction of a graphene oxide based noncovalent multiple nanosupramolecular assembly as a scaffold for drug delivery. Chemistry. 2012;18:4208–4215. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]