Abstract

During a thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan, a 36-year-old male was diagnosed with a solitary oval pulmonary mixed ground-glass nodule in the right upper lobe of the lung. The edge of the nodule was well-defined, and its largest axial size was approximately 1.1×0.9 cm2. This nodule was slightly lobulated, but not obviously speculated. Solid components, micro-cystic lucency shadow, small high-density rings and tiny vascular branches were all visible in the nodule. During hospitalization, a technetium 99 m methylene diphosphonate (Tc-99 m MDP) bone scan was performed, which showed a skeletal foci with abnormal uptake in the left iliac. A pulmonary lobectomy of the right upper lobe of the lung by video-assisted thoracoscopy was performed. In post-operative pathological photomicrographs, proliferative Langerhans’ cells, eosinophils and lymphocytes were found. Immunohistochemistry showed that the expression of S-100 protein, CD1a, and CD68 antigen all stained positive. Since Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (LCH) that is also associated with isolated mixed ground-glass nodules is relatively rare, such a multi-systemic LCH case as identified herein, is reported.

Keywords: Histiocytosis, langerhans’ cells, solitary pulmonary nodule, lung

Introduction

Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare spectrum of diseases that is characterized by aberrant proliferation and accumulation of organs with Langerhans’ cells [1], which are derived from the monocyte-macrophage lineage of the hematopoietic system of the bone marrow microenvironment.

Currently, the pathogenesis of LCH remains unclear. Males were slightly more likely than females to present with LCH, and the pulmonary system is the most frequently involved organ, followed by the bone [2]. The peak age of adults presenting with pulmonary LCH (PLCH) was previously shown to be 20-40 years [3].

High-resolution thoracic computed tomography (CT) is highly specific for the diagnosis of PLCH. However, the diagnosis is oftentimes challenging when solitary pulmonary nodule or cyst is found by CT imaging [4].

Currently, to the best of our knowledge, no previous cases of solitary pulmonary nodule in adult multi-systemic LCH have been reported. However, we report a case of a solitary ground-glass pulmonary nodule, which was diagnosed pre-operatively as lung cancer by CT and confirmed as pulmonary LCH (PLCH) by pathology.

Case presentation

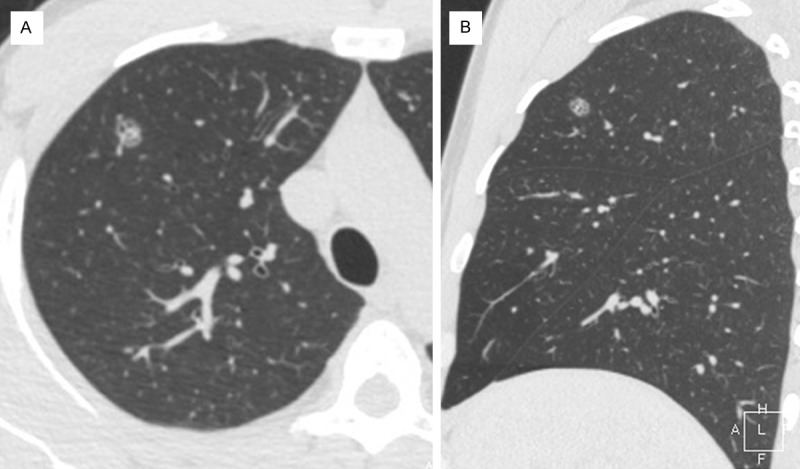

A 36-year-old male volunteered to participate in a protocol that was designed to screen for early lung cancer in Shanghai, China. A solitary oval ground-glass nodule was found in the anterior right upper lobe of the lung. The edge of the nodule was well-defined. There were several factors visible in the nodule, including solid components, micro-cystic lucency shadowing, small high-density rings and tiny vascular branches (Figure 1). The patient smoked on average 10 cigarettes per day for 18 years (9 pack-years) with second-hand smoking exposure, but no other high risk factors that could be related to lung cancer. After admitting to hospital, the patient underwent fiber optic bronchoscopy, cranial magnetic resonance imaging scans, pulmonary function tests, and blood biochemical analyses, which collectively indicated no abnormal findings. Laboratory examination revealed no abnormalities in the blood, urine and stool routine tests.

Figure 1.

A thoracic computer-tomography (CT) scan of a transverse section (A) and a sagittal section (B) that shows a solitary oval pulmonary mixed ground-glass nodule in the right upper lobe.

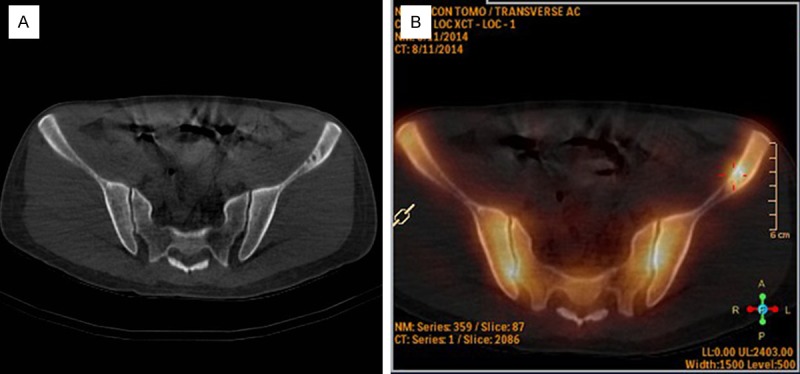

The patient underwent a technetium 99 m methylene diphosphonate (Tc-99 m MDP) bone scan, which presented an abnormal radionuclide dense focus in the left iliac bone. Pelvic CT scans showed a dissolved bony lesion on the left ilium, with dimensions of approximately 1.8×1.1 cm with bony spaces located inside the ileum (Figure 2). We diagnosed solitary pulmonary nodule as pre-operative peripheral lung cancer, and the left iliac lesion was considered metastatic.

Figure 2.

A. Pelvic CT scan showed residues of a bony lesion on the left ilium. B. The technetium 99 m methylene diphosphonate (Tc-99 m MDP) bone scan showed an abnormal radionuclide concentration in the left iliac bone.

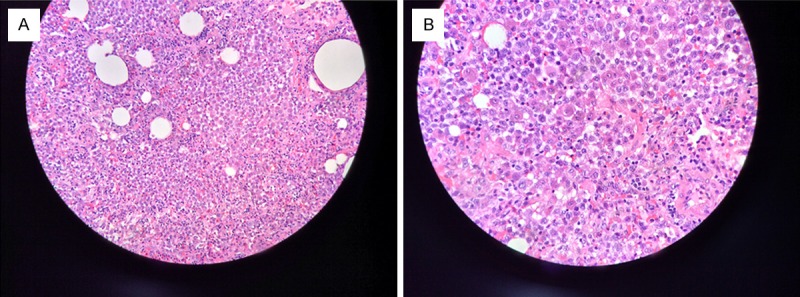

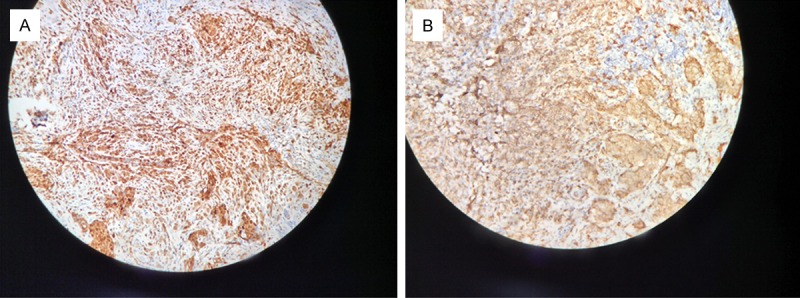

We performed a pulmonary lobectomy of the right upper lung lobe with video-assisted thoracoscopy. Postoperative pathologic photomicrographs of the nodule showed remarkably proliferative Langerhans’ cells with nuclear grooves that were gathered focally or in sheets around the small airways, and inflammatorily infiltrates of eosinophils and lymphocytes (Figure 3) that formed a granulomatous nodule. Additionally, we found that the expression of the S-100 protein, CD1a, and CD68 antigen staining showed a tan positive reaction in Langerhans cells by immunohistochemistry (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

A. Langerhans cells were seen to gather focally or in sheets around the terminal respiratory bronchioles to form granulomas. Histiocytes, and eosinophils were also visible (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×200). B. Langerhans cells showed characteristics of an abundant cytoplasm, were weakly eosinophilic, nuclear groove and sag, and an obvious nucleolus (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×400).

Figure 4.

The expression of the S-100 protein (A) and CD1a antigen (B) staining demonstrated a tan positive colored reaction for Langerhans cells as determined by immunohistochemistry.

Conclusions

Currently, treatment protocols and prognostic guidelines for LCH remain non-unified [5]. Prior studies [6] have reported that application of steroid hormones was effective when treating LCH at an early stage with obvious inflammation; however, the long-term curative effect requires confirmation by large clinical trials. Brauner, et al. [7] reported that 25% of active stage PLCH could spontaneously regress and disappear without treatment. Mogukoc et al. [8] reported that two adults with early stage PLCH experienced complete clearance of the radiological abnormalities without any treatment, although smoking cessation was important. More than 90% patients of PLCH were current and former-smokers [7], while the pathogeny and prognosis of PLCH were closely related to smoking and smoking cessation.

Our case presented with a florid granuloma by pathological imaging, which suggested an activity lesion. Furthermore, a solitary pulmonary nodule by CT scanning might be the initial presentation of multi-systemic diseases with lung infiltration. We content that after quitting, it is possible that the lesion can be completely dissipated without curative intervention by surgical resection. However the initial regression of the nodule by CT imaging did not remain immutable. Tazi et al. [9] described regression of nodule lesions in three cases without treatment, and one case that had received corticosteroids in which were seen recrudescence within seven months up to 7.5 years.

Hence, whether the self-regressed lesions of PLCH in CT were treated or not, they were not thought to have been cured, and thus long-term follow-up was necessary. In considering the damage brought by CT radiation therapy, we have suggested follow-up examination in patients with low-dose CT. We may also refer to the guidelines for lung cancer screening [10] to handle these similar cases to avoid over-treatment; however, the importance of quitting smoking during the follow-up period should be borne in mind. Currently, increasing numbers of small pulmonary nodules can be detected by CT in asymptomatic smokers. Thus, it is both necessary and very important to heighten the cognize to initial stage of PLCH. We submit that PLCH should be considered when a solitary pulmonary nodule is presented in the upper-middle zone, especially with accompanying cystic lucency shadowing, in 20-40 year-old smokers.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the major projects of Biomedicine Department of Shanghai Science and Technology Commission of China (No. 13411950100) for the financial support.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Vassallo R, Ryu JH, Colby TV, Hartman T, Limper AH. Pulmonary Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1969–1978. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006293422607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arico M, Girschikofsky M, Genereau T, Klersy C, McClain K, Grois N, Emile JF, Lukina E, De Juli E, Danesino C. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults. Report from the International Registry of the Histiocyte Society. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2341–2348. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vassallo R, Ryu JH, Schroeder DR, Decker PA, Limper AH. Clinical outcomes of pulmonary Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis in adults. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:484–490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonelli FS, Hartman TE, Swensen SJ, Sherrick A. Accuracy of high-resolution CT in diagnosing lung diseases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:1507–1512. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.6.9609163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castoldi MC, Verrioli A, De Juli E, Vanzulli A. Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis: the many faces of presentation at initial CT scan. Insights Imaging. 2014;5:483–492. doi: 10.1007/s13244-014-0338-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gadner H, Grois N, Potschger U, Minkov M, Arico M, Braier J, Broadbent V, Donadieu J, Henter JI, McCarter R, Ladisch S. Improved outcome in multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis is associated with therapy intensification. Blood. 2008;111:2556–2562. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-106211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brauner MW, Grenier P, Tijani K, Battesti JP, Valeyre D. Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis: evolution of lesions on CT scans. Radiology. 1997;204:497–502. doi: 10.1148/radiology.204.2.9240543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mogulkoc N, Veral A, Bishop PW, Bayindir U, Pickering CA, Egan JJ. Pulmonary Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis: radiologic resolution following smoking cessation. Chest. 1999;115:1452–1455. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.5.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tazi A, Montcelly L, Bergeron A, Valeyre D, Battesti JP, Hance AJ. Relapsing nodular lesions in the course of adult pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:2007–2010. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9709026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood DE, Eapen GA, Ettinger DS, Hou L, Jackman D, Kazerooni E, Klippenstein D, Lackner RP, Leard L, Leung AN, Massion PP, Meyers BF, Munden RF, Otterson GA, Peairs K, Pipavath S, Pratt-Pozo C, Reddy C, Reid ME, Rotter AJ, Schabath MB, Sequist LV, Tong BC, Travis WD, Unger M, Yang SC. Lung cancer screening. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:240–265. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]