Abstract

Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS) is a rare congenital ciliopathy characterised by rod-cone dystrophy, postaxial polydactyly, central obesity, mental retardation, hypogonadism and renal dysfunction. A 45-year-old Indian man presented with New York Heart Association class 2 dyspnoea of 3 months duration. He was blind since childhood. He was obese, cyanosed, and had clubbing and polydactyly. Systemic examination revealed presence of wide and fixed split second heart sound with systolic murmur in the left parasternal area. Work up unmasked the presence of secondary polycythaemia, atypical retinitis pigmentosa and partial atrioventricular defect. He was diagnosed to have BBS based on clinical and radiological features. This case is interesting for its rarity and also for the peculiarity of its cardiovascular association. Polydactyly with a suspicious clinical background is the clue and by itself warrants the clinician to search for occult anomalies. Clinicians must be aware of this syndrome, for which an early diagnosis and a multidisciplinary approach will significantly improve mortality and morbidity in patients.

Background

Bardet-Biedl syndrome is a rare multisystem disorder with retinitis pigmentosa (RP), polydactyly and obesity as its hallmark features. The disease has a high incidence in Newfoundland and Kuwait, due to high consanguinity in these populations. The disease is a rare entity in the rest of the world. Diagnosis of the disease can be made clinically, but confirmation requires genetic analysis. There is no disease-specific treatment, but management of its manifestations and prevention of its complications are of utmost importance, for the disease is fatal only in the late stage.

Case presentation

A 45-year-old Indian man presented to us with symptoms of pedal oedema of 2 weeks duration and New York Heart Association class 2 dyspnoea for 3 months. He was the second child born of a consanguineous marriage. His siblings were normal. The perinatal period had been uneventful. His developmental history was marked by delayed attainment of motor milestones and delay in speech. He had language deficits, a breathy voice and poor schooling skills. He initially developed night blindness when he was seven and was completely blind by 13 years of age. There was delay in development of his secondary sexual characters. He had multiple hospital admissions for respiratory infections, which he was treated symptomatically for, but the underlying disease was left unrecognised. He was diagnosed as having diabetes mellitus at the age of 32 and hypertension when he was 40 years of age. He had worsening breathlessness and pedal oedema, which caused him to present to our hospital.

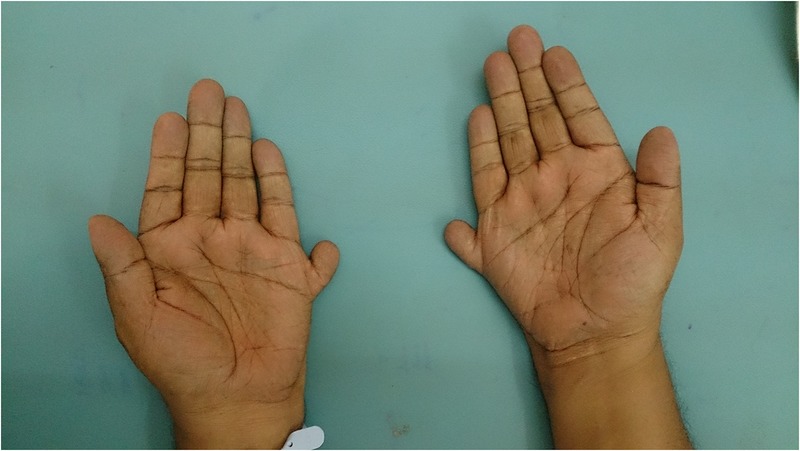

He was 160 cm tall and weighed 92 kg, with a body mass index (BMI) of 35.9 kg/m2. He was completely blind, had marked central obesity, a round face, brachycephaly and postaxial polydactyly (23 fingers; figures 1 and 2). He had central cyanosis and looked polycythaemic. Cardiovascular examination showed a prominent pulsation in the precordial area with a palpable pulmonary component of second heart sound. Auscultation revealed a wide and fixed split second heart sound with a systolic murmur at the base of the heart suggesting atrial septal defect. There was a prominent V wave in the jugular venous pulse with a systolic murmur at the apical area suggesting a cleft mitral valve. The patient's penis and testis were small and hair over the genitalia was sparse. There was no organomegaly on abdominal examination. Neurological examination was normal.

Figure 1.

Brachydactyly with accessory fingers.

Figure 2.

Feet with the accessory 11th toe.

Investigations

Routine investigations revealed hypoxia with secondary polycythaemia and high-blood sugars while lipid profile, and renal and liver function tests were normal.

Urine analysis revealed 3.2 gm proteinuria/day.

Ultrasonography revealed normal renal anatomy.

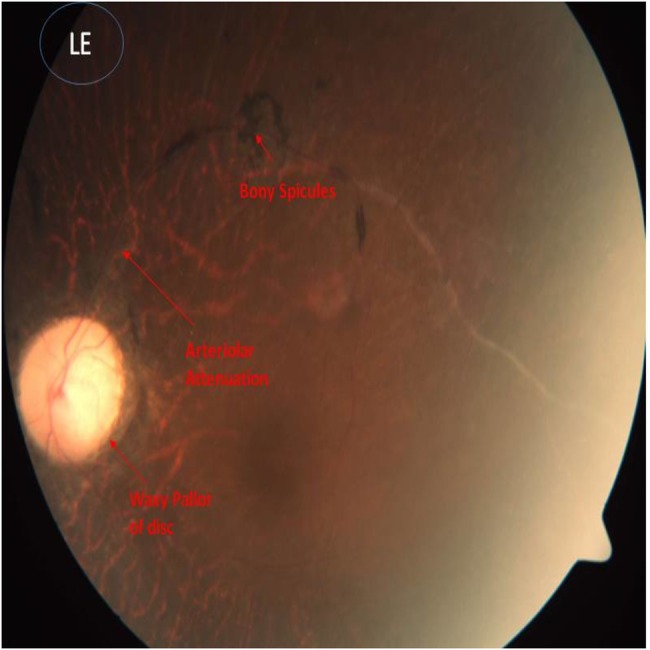

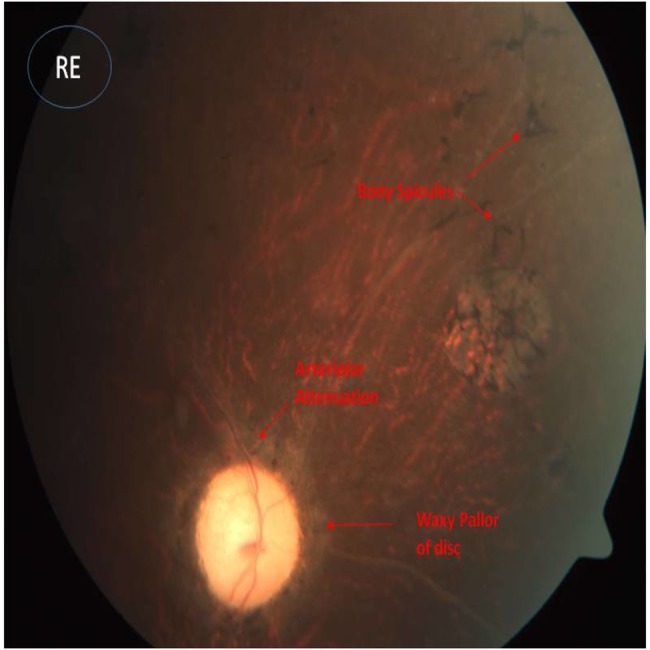

Echocardiography showed partial endocardial cushion defects with common atria, cleft mitral valve and persistent left superior vena cava draining into the coronary sinus (videos 1 and 2). Funduscopy showed atypical RP (figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Funduscopic picture of left eye showing bony spicules, arteriolar attenuation and waxy pallor of disc, which are suggestive of retinitis pigmentosa.

Figure 4.

Funduscopic picture of right eye showing bony spicules, arteriolar attenuation and waxy pallor of disc, which are suggestive of retinitis pigmentosa.

Video 1.

Apical four-chamber view showing both atrioventricular (AV) valves at the same level with large ostium primum atrial septal defect, suggesting partial AV cushion defects.

Video 2.

Para sternal short axis view showing a cleft mitral leaflet.

Differential diagnosis

Laurence-Moon syndrome: the disease has retinal dystrophy, obesity and hypogonadism in common with BBS, but the absence of polydactyly and presence of spasticity differentiates it from the latter.

Ellis-van Creveld syndrome: this syndrome is characterised by short stature, short arms and legs, polydactyly and partial atrioventricular canal defect (AVCD). This can be differentiated from BBS by absence of retinitis pigmentosa, obesity and hypogonadism.

Meckel-Gruber syndrome: this disease comprises the triad of occipital encephalocoele, large polycystic kidneys and postaxial polydactyly. This can be distinguished from BBS by the absence of RP and presence of encephalocoele.

Treatment

The patient was treated symptomatically with diuretics. Amlodipine was substituted with ramipril in view of proteinuria. Phlebotomy was performed for the polycythaemia, to maintain the patient's haematocrit at less than 65%. After consulting a cardiologist, it was decided to keep the patient on conservative medical measures with diuretics and sildenafil. Obesity management was achieved by diet and lifestyle modification. Other supportive care was offered after consulting an occupational therapist, psychologist and social worker.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient's pedal oedema and breathlessness disappeared during his subsequent follow-up. His diuretics were optimised; he was doing fine and was under regular follow-up. He was told about the need for an annual echocardiogram. His family members were counselled about the nature of this disease and its inheritance pattern, and also that consanguinity increases the risk of disease.

Discussion

Bardet-Biedl syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder characterised by rod-cone retinal dystrophy, postaxial polydactyly, central obesity, mental retardation, hypogonadism and renal dysfunction.1 The disease came into light when Laurence and Moon,2 in 1866, described retinal dystrophy, obesity, cognitive deficits and spastic paraparesis in four siblings of a family. Later, Bardet3 and Biedl4 separately reported polydactyly, in addition to the features mentioned above, and coined the term Laurence-Moon-Bardet-Biedl syndrome. However, then this syndrome was thought to represent two separate entities, that described by Laurence-Moon and that reported by Bardet-Biedl, owing to the presence of polydactyly and absence of spasticity in the latter. The slow progression of the disease and its rarity of presentation accounts for late diagnosis of the disease.

The disease is rare, with an estimated incidence of 1 in 150 000–160 000 in North American and European populations, but appears to be high in areas with a high level of consanguinity.5 Fewer than 15 cases have been reported from the Indian subcontinent to date.6 There is a slight male preponderance of 1.3:1.1 The disease is genetically heterozygous and about 19 genes have been known to cause the disease.7 The genes encode BBS proteins, which play a role in ciliary transport. The term ciliopathy is hence used to describe the disease group. The genetic heterogeneity renders genetic analysis expensive and time consuming with its utility restricted to difficult cases or research studies, making it less useful in current routine clinical practice, as diagnosis can be established by clinical criteria alone. However, genetic testing is important, as there are cases of isolated RP caused by mutations in Bardet-Biedl syndrome genes.8 Also, there have been two gene therapy trials in mice with BBS (BBS4 and BBS1), thus opening doors for new potential therapies.9

Clinical diagnosis relies on modified diagnostic criteria set by Beales et al, according to which either four primary features or three primary and two secondary features are required to diagnose the disease (table 1), though retinitis pigmentosa, polydactyly and obesity appear to be the hallmark clinical clues. Polydactyly is a hallmark feature and must alert a physician about the disease in a patient with blindness and obesity. Polydactyly also helps to differentiate the disease from Laurence-Moon syndrome, in which it is absent. Apart from the cardinal features, secondary features worth mentioning include congenital heart defects, dental anomalies, diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus and gait ataxia.

Table 1.

Beales et al. Criteria. Either four primary or three primary and two secondary features are required to diag-nose the disease.

| Primary features | Secondary features |

| Genital anomalies | Dental anomalies |

| Obesity | Diabetes mellitus |

| Polydactyly | Developmental delay |

| Renal anomalies | Congenital heart disease |

| Rod-cone dystrophy | Speech delay |

| Learning difficulties | Brachydactyly/syndactyly |

| Ataxia/poor coordination | |

| Anosmia/hyposmia |

In the Beales et al1 study, congenital heart defects were quite uncommon in BBS, with aortic stenosis, patent ductus arteriosus and cardiomyopathies being more common. In a study by Elbedour et al10 and Moore et al, in 2005, none of the patients had AVCD. These studies are questioned for being older and being published before the elucidation of several BBS genes.1 10 With understanding of the molecular biology behind BBS, clinical evidence supporting the link between AVCD and polydactyly syndromes came into light. In a study by Digilio et al,11 AVCD was found to be the prevalent heart defect. In the latest study by Imhoff et al,12 none of the patients had AVCD. Our patient's echocardiogram revealed partial AVCD along with a cleft mitral valve and persistent left superior venal cava, which was congruent with the Digilio study.

Echocardiographic evaluation to look for potentially treatable cardiac disease is warranted. Radiological evaluation to look for renal anomalies is indicated. Screening for renal cell carcinoma must be performed in patients with a positive family history or if the history is suspicious for a malignancy. Renal disease is one of the leading causes of death and leads to end-stage renal disease requiring renal replacement therapy.

Obesity management, prevention of metabolic syndrome, provision of visual aids, and screening for renal anomalies and for congenital heart defects, are the basic management targets. Early screening for diabetes and its related complications, and avoidance of nephrotoxic drugs and selection of appropriate drugs, will reduce the disease morbidity. This was true for our patient, as addition of ACE or angiotensin receptor blockers could help to reduce the progression of his kidney disease. Management of obesity with diet and lifestyle modification helped in reducing his BMI. The treatment plan also involves an occupational therapist, a social worker and a psychologist. A significant improvement in quality of life can be achieved following the multidisciplinary approach mentioned above.

Learning points.

Clinicians must be aware of this rare entity, for which an early diagnosis and a multidisciplinary approach will significantly reduce mortality and morbidity in patients.

Polydactyly, when associated with other clinical features, must alert a physician to actively search for cardiac and renal anomalies even in asymptomatic patients. Early screening for diabetes, dyslipidaemia and hypertension is warranted. Congenital heart defects are, rarely, seen in Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS).

There is a changing trend towards increased prevalence of partial atrioventricular canal defect, which has previously not been reported. This association has recently been brought into light with the understanding of the biological basis of the disease.

To date, fewer than 15 cases of BBS have been reported from the Indian subcontinent, but none had this association.

Early recognition of BBS followed by echocardiographic evaluation to look for potential treatable cardiac lesions, helps reduce the mortality and morbidity.

Footnotes

Contributors: The idea to write this case was put forward by HMH. The report was written by JM and JS. VA assisted with the literature search and editing.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Beales PL, Elcioglu N, Woolf AS et al. New criteria for improved diagnosis of Bardet-Biedl syndrome: results of a population survey. J Med Genet 1999;36:437–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laurence JZ, Moon RC. Four cases of ‘retinitis pigmentosa’ occurring in the same family, and accompanied by general imperfections of development. 1866. Obes Res 1995;3:400–3. 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00166.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardet G. On congenital obesity syndrome with polydactyly and retinitis pigmentosa (a contribution to the study of clinical forms of hypophyseal obesity). 1920. Obes Res 1995;3:387–99. 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00165.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biedl A. A pair of siblings with adiposo-genital dystrophy. 1922. Obes Res 1995;3:404 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00167.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore SJ, Green JS, Fan Y et al. Clinical and genetic epidemiology of Bardet-Biedl syndrome in Newfoundland: a 22-year prospective, population-based, cohort study. Am J Med Genet A 2005;132A:352–60. 10.1002/ajmg.a.30406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooda AK, Karan SC, Bishnoi JS et al. Renal transplant in a child with Bardet-Biedl syndrome: a rare cause of end-stage renal disease. Indian J Nephrol 2009;19:112–14. 10.4103/0971-4065.57108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forsythe E, Beales PL. Bardet-Biedl Syndrome. 2003 Jul 14 [updated 2015 Apr 23] In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH et al., eds GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle, 1993–2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1363/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrari S, Di Iorio E, Barbaro V et al. Retinitis pigmentosa: genes and disease mechanisms. Curr Genomics 2011;12:238–49. 10.2174/138920211795860107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McIntyre JC, Williams CL, Martens JR. Smelling the roses and seeing the light: gene therapy for ciliopathies. Trends Biotechnol 2013;31:355–63. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elbedour K, Zucker N, Zalzstein E et al. Cardiac abnormalities in the Bardet-Biedl syndrome: echocardiographic studies of 22 patients. Am J Med Genet 1994;52:164–9. 10.1002/ajmg.1320520208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Digilio MC, Dallapiccola B, Marino B. Atrioventricular canal defect in Bardet-Biedl syndrome: clinical evidence supporting the link between atrioventricular canal defect and polydactyly syndromes with ciliary dysfunction 536. Genet Med 2006;8:536–8. doi:10.109701.gim.0000232482.21714.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imhoff O, Marion V, Stoetzel C et al. Bardet-Biedl syndrome: a study of the renal and cardiovascular phenotypes in a French cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;6:22–9. PMC. Web. 7 Jan. 2015 10.2215/CJN.03320410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]