Abstract:

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia can be a life-threatening sequel to conventional use of unfractionated heparin in cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). This study evaluated the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) and efficacy profile of a novel direct thrombin inhibitor, TGN 255, during cardiac surgery in dogs. Point-of-care coagulation monitoring was also compared against the plasma concentrations of TRI 50c, the active metabolite of TGN 255. The study was conducted in three phases using 10 animals: phase 1 was a dose-ranging study in conscious animals (n = 6), phase 2 was a similar but terminal dose-ranging study in dogs undergoing CPB (n = 6), and phase 3 was with animals undergoing simulated mitral valve repair (terminal) using optimal TGN 255 dose regimens derived from phases I and II (n = 4). During the study, PD markers and drug plasma levels were determined. In addition, determinations of hematologic markers and blood loss were undertaken. Phase 1 studies showed that a high-dose regimen of a 5-mg/kg bolus and infusion of 20 mg/kg/h elevated PD markers in conscious animals, at which time there were no measured effects on platelet or red blood cell counts, and the mean plasma concentration of TRI 50C was 20.6 fg/mL. In the phase 2 CPB dose-ranging study, this dosing regimen significantly elevated all the PD markers and produced hemorrhagic and paradoxical thrombogenic effects. In the phase 3 surgical study, a lower TGN 255 dose regimen of a 2.5-mg/kg bolus plus 10 mg/kg/h produced anticoagulation, elevated PD markers, and produced minimal post-operative blood loss in the animals. Plasma levels of TRI 50C trended well with the conventional point-of-care coagulation monitoring. TGN 255 provided effective anticoagulation in a canine CPB procedure, enabling successful completion with minimal blood loss. These findings support further evaluation of TGN 255 as an anticoagulant for CPB.

Keywords: direct thrombin inhibitor (DTI), cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), heparin induced thrombocytopenia

Unfractionated heparin (UFH) has been in continuous use as an anticoagulant for cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) for 60 years (1), but its use can be associated with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), a life-threatening coagulopathy (2–4). HIT incidence in first-time cardiac patients can reach 3% (3,5), with transplant patients experiencing an even higher incidence (6). Overall, there are ∼300,000 cases annually (7). Serious sequelae such as thrombosis, myocardial infarction, and stroke can be manifested in HIT patients (6,8).

To safely restore a post-CPB patient to a more normal coagulation profile and to reverse the coagulopathy that results from normal use of UFH, protamine sulfate is routinely administered. The incidence of catastrophic reaction to protamine sulfate during cardiovascular surgery has been reported to be .13%, whereas all adverse reactions have been reported as high as 10.6% (9,10).

An alternative anticoagulant that is devoid of HIT-related complications, associated with minimal postoperative bleeding risks, and without a need for protamine sulfate reversal is an attractive proposition.

In the coagulation pathway, thrombin is a key serine protease that plays a pivotal role in the amplification mechanisms leading to a burst in thrombin generation. Inhibition of thrombin to produce anticoagulation has become the focus of numerous studies. Pharmacologic manipulation of thrombin has become a strategic target in the development of small molecules that inhibit the active site of thrombin (11,12). Direct thrombin inhibitors (DTIs) have been developed and have shown anticoagulant and anti-thrombotic properties in clinical studies (13,14). In HIT patients, DTIs have been explored as alternative an-ticoagulants. Bivalirudin has been successfully substituted for heparin in CPB (15,16). However, most DTIs have numerous shortcomings including a long half-life, predominant renal excretion, and an unpredictable pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) profile. They are frequently used as off-label pharmaceuticals. Using DTI in cardiac surgery, whether as a substitute for heparin in a HIT patient or as a stand alone anticoagulant, is worthy of further study.

This study describes the anticoagulant activity of a novel DTI, TGN 255. TGN 255 is a highly potent (Ki = 9 nM), selective, reversible thrombin inhibitor, which interacts with the catalytic triad (active site) of the serine protease (17). TGN 255 {[1-[[[1-[1-oxo-2-N-((phenylmethoxy)carbonyl)-3-phenylpropyl]-propline-2-yl]carbonyl]amino]-4-methoxybutyl]-1-boronic acid, sodium salt; Figure 1} is rapidly hydrolyzed to TRI 50c (free acid form), which is the active molecule. TGN 255 has been evaluated in both in vitro and in vivo models and prolongs key PD markers such as thrombin time (TT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and activated clotting time (ACT). TGN 255 is currently being developed as an anticoagulant for intravenous use.

Figure 1.

Structure of TGN 255 (sodium salt).

The primary purpose of this study was to evaluate the PK, PD, and anticoagulant efficacy profile of TGN 255 in a simulated canine mitral valve repair using CPB. The secondary purpose was to study the relationship of common point-of-care coagulation measures with the PK data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ten beagle dogs (drug naïve) of ∼10 kg in body weight were used in this study. All study animals received humane care in compliance with the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” formulated by the National Society for Medical Research and the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996). Before experimentation, each animal received a complete physical examination. Additionally, a complete blood count and biochemical profile (Texas Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory, College Station, TX), platelet count and platelet function (Ichor Platelet Works; Helena Laboratories, Beaumont, TX), ACT, and whole blood thrombin time (WBTT; Hemochron Response; ITC Corporation, Edison, NJ), ecarin clotting time (ECT; Molecular Devices, London, UK), and aPTT and TT (Bioanalytical Services, West Lafayette, IN) were performed before enrollment in the study.

Food was withheld for 12 hours, and each animal was lightly sedated with buprenorphine (14 μg/kg subcutaneously) and diazepam (.2 mg/kg intramuscularly). Both cephalic and jugular indwelling catheters were placed after a local lidocaine infusion. Animals were given TGN 255 using bolus plus infusion dosing regimens (Table 1). All infusions were administered for 90 minutes through the cephalic catheter. Blood samples were collected into citrate from the jugular catheter that was flushed with normal saline (non-heparinized) every 30 minutes to prevent clotting. The citrated blood samples were centrifuged (+4°C), and the derived plasma samples stored at −80°C until needed for analysis of PK, ACT, TT, and ECT. The blood sampling schedule was as follows: time 0 (before bolus dose); 2, 10, and 30 minutes, and 1, 1.5, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 hours.

Table 1.

TGN 255 dosing regimens used in the conscious animal study.

| Compound | Dose |

|---|---|

| TGN 255 (n = 3) | 1.0-mg/kg bolus and then 4 mg/kg/h for 90 minutes |

| TGN 255 (n = 3) | 2.5-mg/kg bolus and then 10 mg/kg/h for 90 minutes |

| TGN 255 (n = 6) | 5.0-mg/kg bolus and then 20 mg/kg/h for 90 minutes |

TGN 255 was evaluated for its PK/PD activity in three phases. Phase 1 consisted of a dose-ranging study on conscious animals, phase 2 consisted of a dose-ranging study in animals placed on CPB, and phase 3 was made up of CPB cases using the optimized dosage of TGN 255.

Surgical Procedures and CPB

A right thoracotomy allowed conventional roller pump CPB with circuit components consisting of single atrial cannulation, antegrade and retrograde cardioplegia, pump suction, hemoconcentrator (Terumo Cardiovascular Systems Corp., Ann Arbor, MI), and pediatric oxygenator (Terumo SX 10R). Circuit prime in each case consisted of Normosol 400 mL (Abbott Labs, Farmers Branch, TX), .9% NaCl 200 mL (Abbott Labs), mannitol USP 2 g, NaHCO3 USP 4 mEq, and 4.4 mg of TGN 255. Cardioplegia delivered 24 mEq/L of K+in a balanced blood and crystalloid solution (dextrose .2% in NaCl (Abbott Labs) 1:1 with circuit blood in a separate 250-mL bag containing .25 g MgSO4, 7.5 mEq KCl, .85 g mannitol, 5.0 mEq NaHCO3, .38 mL of 10% CaCl, and 2.5 mg of lidocaine) and was given at a dose of 15 mL/kg for arrest (aortic root). Half-dose continuous cardioplegia was slowly administered through the coronary sinus during the ischemic period. CPB flows ranged from .9 to 1.2 L/min/m2. Target (esophageal) temperature was 28°C. An unsupported annuloplasty was performed using an approach through the interatrial groove. Warming was timed to allow cross-clamp removal at the 45-minute mark. Restoration of cardiac rhythm was spontaneous. All animals weaned without difficulty.

Main CPB Study

The CPB study was designed to simulate a mitral valve annuloplasty. Ischemic and bypass times (45 and 90 minutes) were consistent throughout the study. All CPB circuits received TGN 255 (providing ∼18 μg/mL concentration) in the prime.

RESULTS

TGN 255 in Conscious Animals

Animals were administered the three doses shown in Table 1, and blood samples were collected for determination of drug plasma levels. These doses produced a dose-dependent increase in TRI 50c plasma concentrations (Figure 2), with maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) values of ∼3, 13 and 23 μg/mL post-bolus, respectively. Serum samples were frozen at −80°C and sent on dry ice to Molecular Devices for standard liquid–liquid extraction of TRI 50c and its 13c5 stable isotope internal standard from plasma (96-well plate technology). The infusions maintained steady plasma concentrations of TRI 50c at all doses. After termination of drug infusion after 90 minutes, plasma concentrations of TRI 50c had declined rapidly within 30 minutes after infusion and returned to baseline by 2.5 hours after infusion. At the highest dose, all the PD markers were elevated as follows (multiples of baseline values): ACT (6 times), WBTT (12 times), TT (16 times) (Figure 3). APTT (2 times) and ECT (>24 times) were also evaluated at 90 minutes (data not shown). The plasma concentration of TRI 50c at 90 minutes was 20.6 ± 3 μg/mL. The six-fold increase in ACT associated with this dosing regimen represents the target value (peak ACT, 426 seconds) used for anticoagulant activity and is comparable with values normally obtained using heparin as the anticoagulant. The 16-fold elevation of TT is below the target of 300 seconds.

Figure 2.

Plasma concentrations of TRI 50c in the conscious dose-range study using bolus plus infusion regimen for 90 minutes. Data values are expressed as mean (μg/mL) ± SEM.

Figure 3.

Changes in pharmacodynamic markers for TGN 255 in the CPB study using a 2.5-mg/kg bolus and 10-mg/kg/h infusion with reducing dose. Infusions were maintained for 90 minutes. Data values are expressed as clotting times (s) ± SD (n = 6).

At all dosing regimens with TGN 255, the functional percentage platelets, red blood cell counts, and platelet counts were not affected.

CPB Dose Ranging

The PD data obtained from the phase 1 dose-range study showed that TGN 255 administered at a bolus dose of 5.0 mg/kg followed by an infusion of 20 mg/kg/h for 90 minutes provided optimum elevated PD markers of TT ∼260 seconds (just below the saturation point of 300 seconds) and ACT and WBTT ∼400 seconds.

In the preliminary CPB study, the selected dosing regimen produced markedly attenuated anticoagulant effects over the conscious animals and culminated in uncontrolled postoperative hemorrhage and paradoxical clotting on the venous sock (Figure 4). Analysis of the hematologic findings showed that this dose of TGN 255 severely affected functional percentage platelets. Analysis of the plasma samples from these CPB animals revealed that the peak plasma concentration of TRI 50c was ∼33 μg/mL compared with 23 μg/mL in the conscious dog study on the same dosing regimen. Therefore, this high dose was dis-continued in the CPB studies. In view of these results, the CPB studies were re-evaluated with a lower TGN 255 dosing regimen (i.e., 2.5-mg/kg bolus and 10-mg/kg/h infusion).

Figure 4.

Paradoxical clotting associated with functional overdose of TGN 255.

Initially, one animal was administered a 2.5-mg/kg bolus followed by a 10-mg/kg/h infusion of TGN 255, and the infusion rate was adjusted as needed to maintain ACT > 400 seconds and WBTT > 350 seconds (Figure 5). This lower dose regimen led to conservation of platelet counts (Figure 6) and functional activity (data not shown) and led to a successful bypass. No clotting was noted on the venous sock, and PD markers after bypass were within the target range.

Figure 5.

Changes in pharmacodynamic markers for TGN 255 using a 5-mg/kg bolus and 20-mg/kg/h infusion in the conscious dose-range study. Data values are expressed as mean (s) ± SD.

Figure 6.

Changes in platelet counts for TGN 255 in the CPB study using a 2.5-mg/kg bolus and 10-mg/kg/h infusion with reducing dose. Infusions were maintained for 90 minutes. Data values are expressed as mean counts (×1000) ± SD.

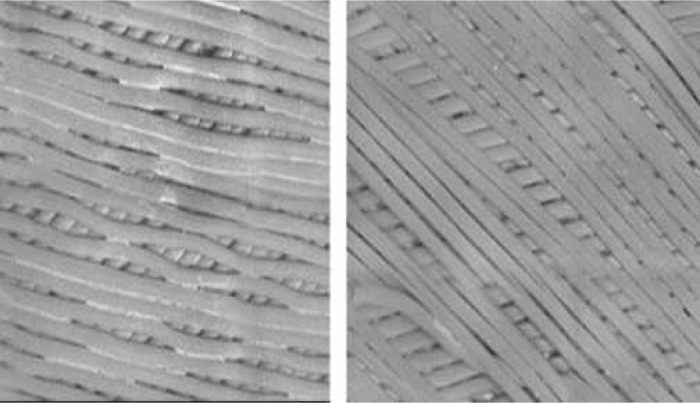

The second animal that received TGN 255 at a 2.5-mg/kg bolus followed by a 10-mg/kg/h infusion in the CPB dose-ranging series performed well in relation to achieving the ACT target values, which returned to 169 seconds (baseline, 73 seconds) by 2 hours after bypass. At this dose, the TRI 50c plasma level achieved was ∼15 μg/mL. However, a small clot was observed on the venous sock (after the procedure), although there was no other evidence of clot formation observed in the circuit. Scanning electron micrographic (SEM) analysis of the central portion of the oxygenator fiber bundle revealed that fibrin deposition was negligible. Our study group was unable to locate similar SEM analysis of oxygenator fibers from heparinized circuits as a reference to what level of fibrin deposition could be expected. Consequently, we examined an identical oxygenator used on a successful (heparin anticoagulation) clinical case on a similar-sized dog and noted considerably reduced fibrin in the presence of TGN 255 compared with heparinized fiber samples (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Side by side comparisons of a 10-kg clinical case with similar ischemic and bypass times using heparin in a conventional fashion with a test subject using a 2.5-mg/kg bolus followed by a 10-mg/kg/h infusion of TGN 255. The heparin case is on the left.

Two further animals were evaluated using this dosing regimen, and both achieved the required PD parameters indicative of TGN 255 anticoagulation with minimal complications. However, despite the reduced dosing regimen, there was still evidence of a clot on the venous sock of one animal. Adjustment of the timing of initiation of bypass to fall ∼30 minutes after bolus dose rather than immediately after bolus solved the cardiotomy clotting. This delay also allowed a second check of the PD markers of anticoagulation.

CPB Studies and Simulated Mitral Valve Repair

In a final series of CPB studies, four animals received TGN 255 as a 2.5-mg/kg bolus with adjustable infusions starting at 10 mg/kg/h and then reducing to 5 mg/kg/h when judged appropriate to maintain the target ACT (>400 seconds). The animals were placed on CPB at a mean time of 34 minutes after bolus. Two dogs required additional small doses (each of 12.5 mg total) to attain the target ACT and WBTT (target >400 seconds) values before going on bypass. These dosing regimens resulted in plasma concentrations of TRI 50c of ∼12 /g/mL and elevated the PD markers as follows: TT (15-to 18-fold), aPTT (4.4-fold), ACT (8-fold; baseline, 86 seconds), WBTT (15-fold), and ECT (>600 seconds). All four dogs survived with no complications. Mean operative and post-operative blood loss in this group was 112 ± 24.3 (SD) mL (16% ± 3.5% total blood volume). Each animal had one 55-mL bowl of their thoracostomy tube drainage washed and returned after 1 hour (Electa; Cobe Cardiovascular, Arvada, CO). Thoracostomy tube drainage was minimal (<50 mL) after the first hour. The animals were hemodynamically stable 4 hours after bypass and showed no bleeding tendency. Furthermore, echocardiographic measurements at 4 hours post-operatively compared favorably with preoperative echocardiograms showing expected minimally diminished but still robust cardiac function.

Pharmacokinetic Profile of TGN 255

The plasma samples derived from the CPB studies were analyzed for TRI 50c, the active form of TGN 255; total doses ranged from 13.3 to 23.6 mg/kg, with a mean (n = 10) of 17.4 mg/kg. Good systemic drug exposure was observed, allowing estimates of plasma half-life (t1/2), Cmax, time to peak plasma concentration (Tmax), total drug exposure (area under the curve from zero-time and zero-infinity; AUC0–t and AUC0–∞).

The Tmax values varied according to the dosing regimens used and ranged from 10 to 50 minutes. The corre-sponding Cmax values ranged from 9.41 to 24.0 μg/mL, with an overall coefficient of variance (CV) of 29.9% (mean = 16 μg/mL, n = 6). The mean (n = 6) AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ values were 23.06 and 24.23 μg/h/mL, with a CV of 28.4% and 27.9%, respectively, indicating that the extrapolated area to infinity was <5% of the total, with only low levels of TRI 50c remaining 6 hours after start of dosing.

The estimated t1/2 values ranged from 1.36 to 2.14 hours (n = 6; mean of 1.68 hours, 20.7% CV), indicating that TRI 50c would be cleared from the systemic circulation rapidly after the end of infusion; this was consistent with the low AUC extrapolations from the last time point to infinity. In addition, the clearance values ranged from 3.9 to 9.2 L/h, which would also be indicative of a rapid systemic clearance.

DISCUSSION

The pharmacologic actions of thrombin play a significant role in modulating the activation of the coagulation pathway. Thrombin generation is greatly enhanced when blood is in contact with the CPB surface, thus leading to activation of coagulation mechanisms. Inhibition of thrombin is a crucial process in cardiac surgery involving CPB. Anticoagulation has been achieved historically by heparin, which is associated with induction of thrombocytopenia and thrombotic-related complications. Attempts have been made using animal models to produce anticoagulant activity during CPB with thrombin inhibitors, including thrombin-aptamers, recombinant hirudin, DUP 714 (peptide thrombin inhibitor), and argatroban (18–21). Although these agents have displayed successful anticoagulant efficacy in CPB situations, there is still a need to develop drugs that exhibit a safe and predictable PK/PD profile. The dynamic coagulation/anticoagulation environment surrounding CPB responds best to point-of-care monitoring, and this study showed the correlation of plasma concentration with common coagulation tests.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the PD/PK profile of Trigen’s clinical candidate TGN 255 in a CPB setting. In pre-clinical studies, TGN 255 has been shown to be a highly potent, selective, and reversible direct thrombin inhibitor. In clinical studies, TGN 255 administered as a bolus and/or bolus followed by infusion dosing regimens displayed a PK/PD profile that is highly reproducible and predictable. The onset of TGN 255 anticoagulant activity is rapid, with corresponding elevations of ACT, TT, and aPTT markers. Termination of infusions leads to a rapid decline in plasma concentrations and a reduction in PD markers. Therefore, based on both pre-clinical and clinical findings, TGN 255 was selected for evaluation as an anticoagulant for cardiac surgery with CPB.

TGN 255 in Conscious Animals

TGN 255 was administered using a bolus plus infusion regimen at three doses in conscious animals to obtain an anticoagulant profile. Plasma drug concentrations of TRI 50c, the active form of TGN 255, increased in a dose-dependent manner. As expected from pre-clinical and clinical studies, increasing plasma concentrations of TGN 255 produced a corresponding elevation of the pharmacodynamic markers including TT, ACT, WBTT, ECT, and aPTT. The ACT values were elevated by TRI 50c to ∼400 seconds by the two highest doses. When the TGN 255 infusion was terminated, the plasma drug levels began to decline rapidly. As measured by the Ichor Platelet Works, TGN 255 had no effects on red blood cell or platelet counts. As background for the use of the PlateletWorks, a preliminary study of 20 normal dogs showed accurate correlation with our standard laboratory tests.

TGN 255 and Canine CPB Study

The pharmacokinetic findings of TGN 255 under cardiac surgical conditions with simulated mitral valve repair with CPB showed that the peak plasma concentrations are reached rapidly, with Tmax ranging from 0.17 to 0.83 hours, whereas Cmax was 9–24 μg/mL. The t1/2 value was ∼1.6 hours, indicating that TRI 50c would be cleared rapidly from the systemic circulation on termination of the infusion.

The application of the derived dosing regimen in the animals on CPB led to a rapid and prolonged saturation of all the pharmacodynamic parameters, hemorrhagic effects, and paradoxical visible clots were observed on the venous sock. The exact mechanism of these disparate results was not investigated in this study. One can surmise that, because the animals were subjected to hypothermic and serum dilutional conditions that would inevitably reduce hepatic enzyme activity and hepatic metabolism, there would be an expected prolonged drug clearance. This is corroborated by the higher TRI 50c plasma concentrations (1.4-fold increase compared with conscious dog study) in this group.

The application of a low-dose TGN 255 regimen in CPB studies (i.e., 2.5-mg/kg bolus plus 10-mg/kg/h infusion) led to a significant reduction in the drug plasma concentrations from 33 (at 5-mg/kg bolus plus 20-mg/kg/h infusion) to 23 μg/mL. Consequently, this protocol modification had a great impact on lowering the effects on the pharmacodynamic markers. Despite this change, the ACT values were still considered too high (>1000 seconds), and there was evidence of clot formation on the venous sock. Further protocol modifications in the dosing regimen with infusion reductions culminated in a 9-and 11-fold increase in TT and WBTT, respectively, whereas aPTT and ACT had been elevated by 2-and 5-fold above baseline. These elevated markers led to acceptable blood loss in the animals when using the bolus plus infusion dose regimen followed by initiation of CPB at 30 minutes after bolus.

It is well documented that, during CPB, platelet numbers decline rapidly, and in this study, similar effects were also observed. However, by using a modified protocol of delaying the CPB after bolus administration, subsequent infusion reductions maintained the platelet count at ∼5× 104. Therefore, in this surgical setting, TGN 255 had minimal effects on both platelet and red blood cells counts. In addition, TGN 255 had no adverse effects on cardiac function after CPB. The efficacy of TGN 255 as an anticoagulant was further shown by electron micrographs of the oxygenator fiber bundles that exhibited minimal evidence of fibrin deposition. Hence, the new protocol parameters allowed the safe use of TGN 255 in the experimental cardiac surgery with associated CPB.

Overall, TGN 255 produced adequate anticoagulant ef-fects, maintained targeted pharmacodynamic marker elevations, and exhibited an excellent pharmacokinetic profile. Of particular interest was the predictable correlation between the ACT and the TRI 50c plasma levels. With point-of-care monitoring, a degree of confidence in adjusting the infusion rate to pinpoint a target level of anticoagulation developed. The blood loss observed during CPB with TGN 255 was low, and chest tube drainage rapidly tapered off. These pharmacologic properties of TGN 255 show that, in this experimental setting, TGN 255 is efficacious and safe to use in a CPB setting. Further clinical study is warranted.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hyers TM.. Management of venous thromboembolism: past, present, and future. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:759–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiess BD.. Update on heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and cardiovascular interventions. Semin Hematol. 2005;42:S22–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rice L.. Evolving management strategies for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Semin Hematol. 2005;42:S15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deitcher SR, Carman TL.. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: natural history, diagnosis, and management. Vasc Med. 2001;6:113–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warkentin TE, Sheppard JA, Horsewood P, et al. Impact of the patient population on the risk for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2000;96:1703–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hourigan LA, Walters DL, Keck SA, Dec GW.. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a common complication in cardiac transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002;21:1283–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anonymous. American Heart Association: Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics–2005 Update. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartholomew JR, Begelman SM, Almahameed A.. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: principles for early recognition and management. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72(Suppl 1):S31–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy JH, Zaidan JR, Faraj B.. Prospective evaluation of risk of protamine reactions in patients with NPH insulin-dependent diabetes. Anesth Analg. 1986;65:739–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiler JM, Gellhaus MA, Carter JG, et al. A prospective study of the risk of an immediate adverse reaction to protamine sulfate during cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990;85:713–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saiah E, Soares C.. Small molecule coagulation cascade inhibitors in the clinic. Curr Top Med Chem. 2005;5:1677–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Nisio M, Middeldorp S, Buller HR.. Direct thrombin inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1028–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brighton TA.. The direct thrombin inhibitor melagatran/ximelagatran. Med J Aust. 2004;181:432–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gustafsson D.. Oral direct thrombin inhibitors in clinical development. J Intern Med. 2003;254:322–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warkentin TE, Greinacher A.. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:638–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koster A, Chew D, Grundel M, et al. Bivalirudin monitored with the ecarin clotting time for anticoagulation during cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:383–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elgendy S, Deadman J, Claeson G.. New peptide boronic acid inhibi-tors of thrombin. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1993;340:173–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walenga JM, Bakhos M, Messmore HL, Fareed J, Pifarre R.. Potential use of recombinant hirudin as an anticoagulant in a cardiopulmonary bypass model. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;51:271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeAnda A Jr, Coutre SE, Moon MR, et al. Pilot study of the efficacy of a thrombin inhibitor for use during cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58:344–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chomiak PN, Walenga JM, Koza MJ, et al. Investigation of a thrombin inhibitor peptide as an alternative to heparin in cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. Circulation. 1993;88:II407–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rikitake K, Okazaki Y, Naito K, et al. Heparinless cardiopulmonary bypass with argatroban in dogs. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25: 819–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]