Abstract:

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is a complex task requiring high levels of practitioner expertise. Although some education standards exist, few are based on an analysis of perfusionists’ problem-solving needs. This study shows the efficacy of work domain analysis (WDA) as a framework for analyzing perfusionists’ conceptualization and problem-solving strategies. A WDA model of a CPB circuit was developed. A high-fidelity CPB simulator (Manbit) was used to present routine and oxygenator failure scenarios to six proficient perfusionists. The video-cued recall technique was used to elicit perfusionists’ conceptualization strategies. The resulting recall transcripts were coded using the WDA model and analyzed for associations between task completion times and patterns of conceptualization. The WDA model developed was successful in being able to account for and describe the thought process followed by each participant. It was also shown that, although there was no correlation between experience with CPB and ability to change an oxygenator, there was a link between the between specific thought patterns and the efficiency in undertaking this task. Simulators are widely used in many fields of human endeavor, and in this research, the attempt was made to use WDA to gain insights into the complexities of the human thought process when engaged in the complex task of conducting CPB. The assumption that experience equates with ability is challenged, and rather, it is shown that thought process is a more significant determinant of success when engaged in complex tasks. WDA analysis in combination with a CPB simulator may be used to elucidate successful strategies for completing complex tasks.

Keywords: perfusionists, education, CPB simulator, work domain analysis, cardiopulmonary bypass

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is an exacting discipline. Although several standards define training requirements (1,2), few involve a systematic analysis of CPB circuit problem solving. Effective education programs may improve perfusionists’ problem-solving abilities and thus reduce the risk of adverse consequences for patients (3–6). However, developing an effective training program depends on a detailed understanding of the CPB circuit, the cognitive strategies perfusionists use (7–9), and the difficulties they encounter.

Work domain analysis (WDA) was developed from detailed analyses of operator problem conceptualization in the nuclear power industry (7–10) and has since shown its usefulness in complex medical (10–12) and non-medical contexts (11,13,14). WDA involves systematically modeling the work environment in ways that are consistent with human problem conceptualization (7–14).

Simulators have been used to enhance training in many safety critical fields. In anesthesia, 158 worldwide centers (15) use simulators to train anesthetists in technical and team-based skills (16–18). Simulators facilitate realistic problem solving in safe environments and are ideal contexts for human performance research.

The purpose of this study is to show the efficacy of WDA as a basis for analyzing perfusionists’ conceptualization processes during simulated routine and CPB circuit failure situations. Findings may be used to guide further research aimed at developing recommendations for educational requirements in this field.

Algorithms, flow diagrams that present the logical order of task steps, are commonly used for managing emergency situations (19–22). Algorithms are highly effective when events unfold predictably (23), but they may be inadequate when situations occur rarely, are complex, or vary from the expected path. In these situations, people must rely on their own reasoning strategies to manage the situation. WDA is a means for analyzing clinical reasoning strategies and their effectiveness.

In complex technological environments, experts use one or a combination of two reasoning approaches when working with high hazard situations (7,8). People may reason in terms of parts. If a particular valve fails, for example, a person may reason in terms of the valve’s location in the system and its effect on other components. This is structural whole part reasoning. A different person may reason about the same failure using abstract reasoning; thus, the valve failure would be considered in terms of its purpose or reason for existence and how this purpose may be fulfilled by alternative means.

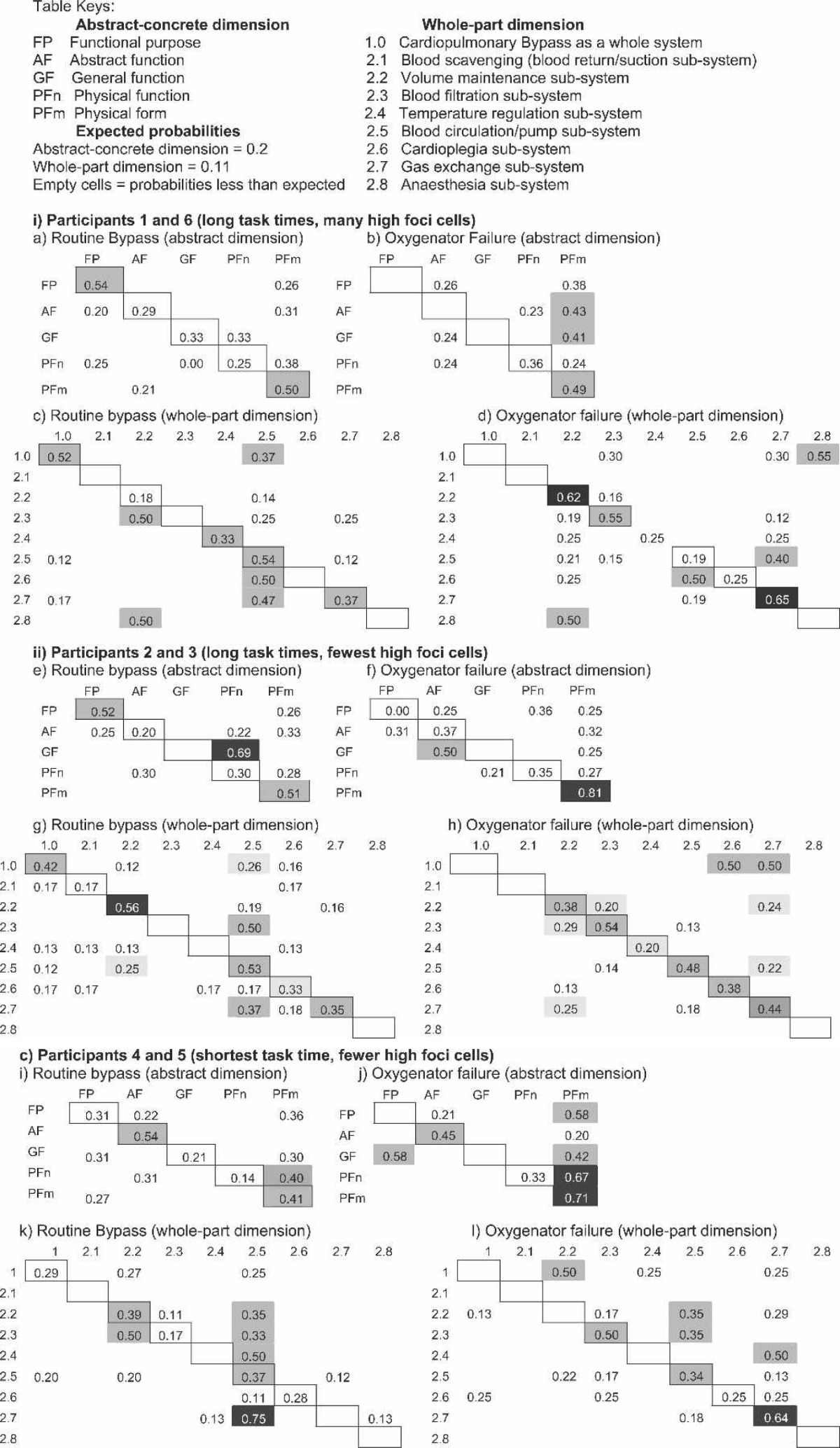

A WDA is a framework that describes complex technical systems in terms of whole part relations and in terms of different levels of abstract reasoning. For any particular system, a WDA is developed using technical specifications and blueprints, physical inspection, textbooks and manuals, and expert consultation. The result is a description of the technical system in a two-dimensional matrix. Figure 1 shows one column in the matrix. This vertical axis represents the function of maintaining blood flow during CPB and the different levels of abstraction that apply to this function. The complete WDA matrix is a synthesis of eight separate functions that include minimizing total blood loss, maintaining closed circuit integrity, preventing clots and air bubbles from entering the systemic circulation, controlling systemic temperature, maintaining systemic blood flow, achieving and maintaining cardiac arrest, maintaining cellular gas exchange, and maintaining a state of anesthesia. Using this matrix, we can map the reasoning paths that perfusionists use to solve routine and rare CPB problems.

Figure 1.

WDA of the CPB environment.

We propose that the most effective reasoning strategy in rare situations is one that includes both abstract and whole part reasoning.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Six perfusionists volunteered 3 hours of their time to participate. The study was held over 2 weeks in a vacant operating room at Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, in April 2005. Participants’ demographic profiles are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic characteristics.

| Participant | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Age range (yr) | 46–55 | < 35 | 46–55 | 35–45 | 35–45 | 35–45 |

| Years of CPB experience | 12 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| No. of CPB cases | > 200 | 51–100 | 101–200 | > 200 | < 50 | > 200 |

| Simulator experience | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Materials

Three sets of materials were used as described below.

High-Fidelity CPB Simulator:

A CPB simulator (Manbit, Sydney, Australia) produced high-fidelity simulations of normal and abnormal perfusion situations. The Manbit simulator was used with a Jostra HL20 heart-lung machine (MAQUET Cardiopulmonary, Hirrlingen, Germany) and standard monitoring equipment. The oxygenator circuit and tubing were donated by a leading supplier (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Simulator on operating table connected to CPB machine in the background.

Head-Mounted Audio-Video Recording Equipment:

A small microphone and camera lens mounted on a headband was fitted to the participants’ heads (19). The camera lens and microphone were connected to a camera, battery power supply, and sound recording equipment that were carried in a small backpack weighing 3 kg. Participants had freedom of movement untethered by cords or leads (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Participant with head-mounted camera.

Recall Recording Equipment:

A television monitor and over-the-shoulder camera and tripod were used to record recall interviews cued by the head-mounted recordings.

Other materials included three scenario patient profiles, scenario outline sheets indicating surgical milestones (e.g., go on bypass), and a stopwatch to time scenario completion. The outline sheet was used to control scenario presentation so that differences in completion times could be attributed to participant behavior rather than to scenario presentation variability.

Procedures

After consent, participants were separately asked to complete four scenarios presents in a fixed format. Participants were informed that the scenarios may or may not involve circuit failures but would not involve patient or surgical emergencies. The first scenario involved setting up and priming the CPB circuit. This scenario familiarized participants with the simulator environment and the head-mounted equipment and was excluded from further analysis. Using the prepared circuit, the participant was presented with the first patient profile, which involved a routine mitral valve replacement. The participant was required to go on bypass, administer cardioplegia, maintain, and come off bypass. These scenarios were included to allow the participants to become acquainted and comfortable with the simulator and the equipment.

The third and fourth scenarios, both involving coronary artery bypass graft procedures, were failure scenarios. The first failure scenario was an oxygen line disconnection and the second involved an oxygenator failure. In both scenarios, participants were asked to start the procedure from the “go on bypass” stage. All scenarios were recorded using the head-mounted recording apparatus. Taken from the perfusionists’ heads, recordings included the objects and information attended to by the perfusionist but did not record participant images (25).

Having completed all scenarios, the participant was seated before the television monitor and asked to replay the scenario recordings recalling aloud “what was going through their minds” during the scenarios. Participants could pause the recording so that commentary did not lag behind. The recall sessions were recorded using an over-shoulder camera mounted on a tripod. This procedure was based on the video-cued recall protocol developed by Omodei et al. (25).

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, Australia.

Data Collation

After transcription of the audio tapes, the content of each sentence (26) was coded according to the WDA matrix, and the codes were arranged to form a Markov chain (27) as shown in Table 2. Markov chains are used to analyze processes that involve transitions from one state or step to another. If a person is thinking about CPB filters, for example, his next thought may continue to be about filters or it may move on to thinking about fluid lines; alternatively, if a person is thinking about purposes, she may continue to think about purposes or may move on to some level of abstraction such as performance measures. Markov chains allow us to analysis the probability of transitioning from one state to another in reasoning processes (28). In this research, Markov chains were used to compare participant’s reasoning processes when engaged in the CPB scenarios.

Table 2.

Part of a Markov chain for the oxygenator failure scenario.

| Speech Unit Number | Abstract-Concrete Code | Whole-Part Code | Text |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AF* | 2.7† | Yeah. Now it’s [oxygen saturation’s] 66 |

| 2 | PFm | 2.7 | I’m thinking well there is something wrong with this oxygenator |

| 3 | PFn | 2.5 | OK. Turn the flow up |

| 4 | AF | 2.7 | To improve the saturation |

| 5 | PFn | 2.7 | I’m just double checking that that’s still connected [filter connection] |

| 6 | PFn | 2.5 | Going up on the flow’s |

| 7 | FP | 2.5 | The only way you can improve the cardio output |

| 8 | FP | 2.7 | And put the sat[uration] up |

| 9 | AF | 2.7 | Now once this gets below 50 I’m starting to think there’s something wrong with this. I don’t like the sat[uration]s around 50 |

| 10 | PFm | 2.7 | Everything else is working perfectly so it’s got to be a problem with the oxygenator. Now you’ve got to make a decision. You’ve got to decide whether to get rid of it or not |

Abstraction dimension categories: FP, functional purpose; AF, abstract function; GF, general function; PFn, physical function; PFm, physical form.

Decomposition dimension categories: 2.5, blood flow functions; 2.7, oxygenation functions. The terms specifically coded in each phase are highlighted in the “Text” column.

Based on Markov chains, three analyses were undertaken according to the following research questions.

Are there associations between the number of strong foci cross-tabulation cells and routine and oxygenator failure scenario completion times?

Are there conceptual differences between routine and oxygenator failure scenarios for participants with the fastest and slowest oxygenator failure resolution times?

What problems do participants encounter?

RESULTS

Associations Between Numbers of High Probability Transitions and Scenario Completion Times

An initial Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated for participant’s task completion times and past CPB experience. There was no statistically significant correlation between task completion times and past experience.

Table 3 represents the cross-tabulation of the thought process of one participant when engaged in the task of changing an oxygenator. A cell in which the value is 0.00 means that the participant never thought about that particular concept or issue when engaged in the task. Any cell with a value >0.00 represents a specific thought process in which the participant engaged. The higher the value in each cell, the more frequently the participant returned to that thought. For example, when engaged in changing an oxygenator, the participant may never think about minimizing blood loss but will allow their thoughts to return frequently to the issue of maintaining cellular gas exchange.

Table 3.

Cross-tabulation of one participant conducting oxygenator change-out.

| 1.00 | 2.10 | 2.20 | 2.30 | 2.40 | 2.50 | 2.60 | 2.70 | 2.80 | |

| FP | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| AF | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.00 |

| GF | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| PFn | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| PFm | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

The expected frequency in each cell is 0.02. A strong focus cell (gray shading) represents a frequency ≥ 0.04.

1.00, whole CPB conceptualization; 2.10, minimize total blood loss; 2.20, maintain closed circuit integrity; 2.30, prevent clots and air entering circulation; 2.40, maintain systemic temperature; 2.50, maintain systemic flow; 2.60, achieve cardiac standstill; 2.70, maintain cellular gas exchange; 2.80, maintain anesthesia. FP, functional purpose; AF, abstract function; GF, general function; PFn, physical function; PFm, physical form.

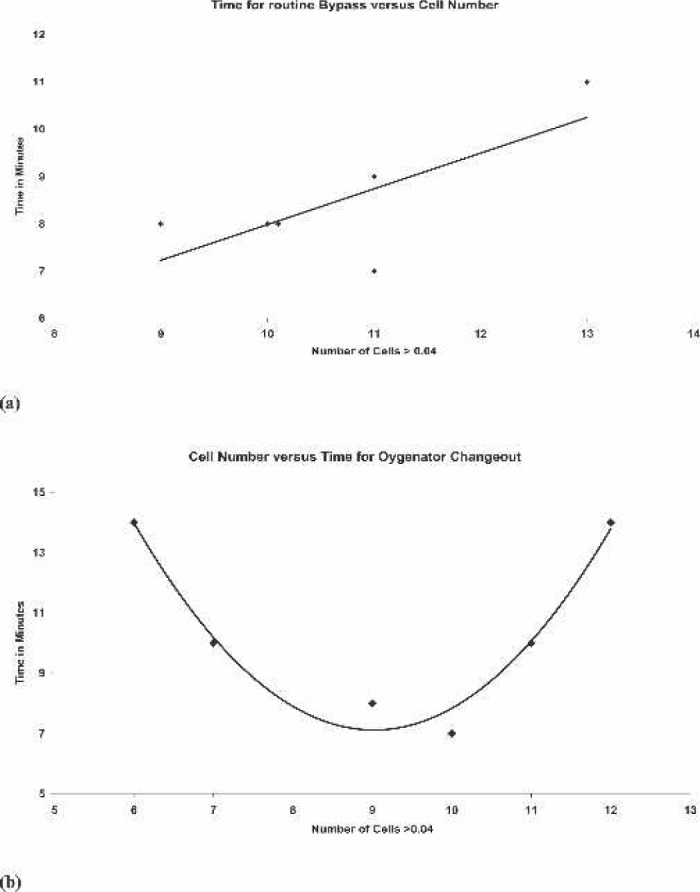

Statistical analysis was undertaken using regression analysis to determine the significance of association between task completion time and number of high probability transitions for routine and oxygenator failure scenarios. High probability transitions were cross-tabulation cells with probabilities equal to or greater than twice the expected cell value (in a 5 × 9 matrix, expected probabilities are 1/45 = 0.02; 0.04 is twice the expected value). Scatterplots were used to guide the application of the regression tests. Figure 4 shows scatterplots for the routine and oxygenator failure scenarios with participants indicated by randomly allocated numbers.

Figure 4.

Scatterplots for the routine and oxygenator failure scenarios. Number of strong foci cells from cross tabulation table plotted against time taken for task. (a) Routine bypass and (b) oxygenator failure.

The scatterplots compared the number of strong foci cells in the cross-tabulation table for each participant with the time they took to complete a routine setup and changing an oxygenator (Figure 4). In the routine setup vs. time comparison, there is a clear linear relationship between the two variables. It is shown that increasing dispersion of a participant’s attention (increased number of strong foci cells) is associated with increasing time taken to perform a routine setup. Linear regression analysis of this association showed a statistically significant association between the variables, with p < .016. The situation with the oxygenator change out was somewhat different, and the scatterplot shows an inverse parabolic relationship between the number of strong foci cells and time to change an oxygenator.

This suggests that it takes a participant longer to change an oxygenator if their thoughts are either too focused (smaller number of strong foci cells) or dispersed (increased number of strong foci cells). The participants that achieved the optimum result had a level of thought focus between these two extremes. The statistic used to analyze these results is a quadratic regression model, and in this instance, p < .007.

Time was chosen as one the measures of expertise in changing an oxygenator because the deleterious physiologic effects of increased lengths of hypoxia are well documented.

All the participants were able to make an early diagnosis of oxygenator failure as the mixed venous saturations on the simulator decreased.

Conceptualization Patterns for Routine and Failure Mode Scenarios

Participants were divided into three groups: participants 1 and 6 (long task times, many high foci cells); participants 2 and 3 (long task times, fewest high foci cells), and participants 4 and 5 (shortest task times, few high foci cells). Table 4 shows Markov matrices of mean proportions for the three groups for each of the scenarios.

Table 4.

Mean Markov partial proportions for participants 1 and 6; 2 and 3; and 4 and 5.

On the abstract-concrete dimension, participants 1 and 6 and 2 and 3 showed similar distributions of conceptual foci for the routine scenario (Table 4). Both groups focused on functional purposes (FP) and concrete objects (PFm). Similarly, on the whole part dimension, both groups focused within functional subsystems (Table 4, main diagonal-boxed cells), with some moderate foci representing subsystem interrelations (Table 4, off-diagonal cells).

These patterns shifted in the oxygenator failure scenario. Participants 1 and 6 considered higher levels of abstraction, especially system operating priorities, in terms of concrete objects (Table 4, far right column) across a limited range of subsystems (Table 4, main diagonal). Participants 2 and 3 limited their abstract focus to concrete relations among objects (Table 4, see PFm/Pfm cell) across a range of subsystems (Table 4, main diagonal).

In contrast, participants 4 and 5 used similar patterns of abstract-concrete conceptualization in both scenarios (Table 4). Participants 4 and 5 focused strongly on operating priorities (AF) in relation to concrete objects and considered important subsystems in relation to other subsystems. In the oxygenator failure scenario, the abstract-concrete pattern was strengthened (Table 4, far right column). In the whole part dimension, participants 4 and 5 focused on particular subsystems, and to an almost equal degree, focused on sub-system interrelations as illustrated in the columnar spread of higher probabilities in Table 4.

Problems Encountered by Participants

Technological and/or procedural issues were encountered by all participants. No participants completed the oxygenator failure scenario in <6 minutes (Figure 4).

Issues Associated With Technology

Technological issues involved CPB circuit line clamps, clips, and caps.

Line Clamps:

To change an oxygenator in mid-procedure, blood circulation is stopped, the failed oxygenator is detached, all line attached to the oxygenator are cut, a new oxygenator is reattached and fluid-primed, and bubbles are removed. This process requires no less than 10 and up to 12 line clamps. There is no indication on the circuit as to where the clamps should be placed. Two clamps are used on lines to be cut; the cut is made between the clamps. Two participants did not leave enough room between the double clamps and lost time repositioning them; one participant accidentally cut a line that did not need to be cut, and another participant cut on the wrong side of the double clamp. Up to four clamps are used to direct fluid through the lines so that bubbles are filtered out. Three participants either misplaced or missed placing at least one clamp, allowing bubbles into the circuit, which had to be further de-aired. Patient outflow and inflow lines are also clamped. Three participants missed unclamping one of these, resulting in an obstruction that needed to be resolved, and another did not clamp a line tightly enough, resulting in fluid loss on the floor.

Oxygenator-Reservoir Clip:

The oxygenator comes packed and connected to the reservoir by a C clip that can only be replaced in one way with difficulty. There is no functional relationship between the oxygenator and the reservoir except through connecting tubes that are not part of the C clip assembly. Two participants lost time reconnecting the oxygenator to the reservoir by replacing the one-way clip. Two participants attempted to replace the clip and gave up, with one asking an assistant to hold the oxygenator and the other participant placing the oxygenator on the floor.

Two participants made no attempt to replace the C clip and optimally left the new oxygenator on a towel on the floor.

Missing Caps:

Several ports on the oxygenator are closed by luer-lock caps. In two cases, the caps became dislodged, allowing air to enter the oxygenator, resulting in the need to repeat the de-airing process.

Procedural Problems

One participant erroneously assumed that the replacement oxygenator would be pre-primed and connected to the reservoir. On this basis, all lines from the oxygenator and the reservoir were clamped and cut. On receipt of the un-primed oxygenator without the reservoir, a new approach needed to be devised.

In this case, the risk to a real patient may have been minimized. During an oxygenator change-out, patients are at high risk of hypoxic brain damage. This participant was one of two who minimized this risk by cooling the patient to 26°C and ordering the administration of anesthetic agents to reduce brain oxygen consumption. Although other participants may have neglected this step given the simulation environment, the heightened levels of arousal observed when participants realized that the oxygenator had failed and throughout the scenario suggest that participants were fully engaged in it. Four participants later observed that the most difficult part of the session was deciding that the fourth scenario was an oxygenator failure; three participants lost time exploring alterative possibilities.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this research was to demonstrate the feasibility of analyzing perfusionists’ conceptualization strategies in routine and failure scenarios using a WDA approach in a high-fidelity simulator environment. This study introduced a novel methodologic approach based on established practices in anesthesia simulation (16–18) and engineering psychology (7–9). The use of video-cued recall, which is claimed to reduce participant bias associated with unaided retrospective recall and observer bias in behavioral observation studies (24,25), is also novel.

The human thought process is extremely complex, and WDA in conjunction with a high-fidelity simulator seems to offer insights into some of these complexities. The findings challenge the assumption that increasing levels of experience are associated with improved ability to solve complex, emergency situations, and rather, present evidence that efficiency of an individual’s thought process is more important. The participant who was best able to manage the oxygenator failure had <50 completed cases of CPB in their log book. One of the participants who took the longest to change the oxygenator had previous simulator experience in this exercise and >10 years of continuous experience in perfusion. The results of this study suggest that, when events do not play out as expected, performance efficiency depends on perfusionists having the conceptual tools to adaptively work through problems as they present.

Developing adaptive skills may be quite straightforward. Efficient perfusionists reused conceptualization patterns in problem situations that were evident in routine situations and, while being as disposed to technological difficulties as the other participants, were better able to accommodate these without the same performance decrement. Thus, training strategies that emphasize flexible conceptualization in routine situations may provide the conceptual basis for adaptive problem solving in unexpected situations.

The implications are that further research is needed to identify and describe successful strategies in managing complex situations in CPB, and the application of these in the training curriculum may improve the quality of perfusion education.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Richard Morris for the use of the Man-bit simulator and Prof. Penny Sanderson for suggestions during the conceptualization phase of this research. We thank the oxygenator circuit supplier who has asked not be identified. We especially thank the perfusionists at PAH for enthusiastic support. Statistical input was provided by Dr. Mark Jones, Biostatistician, University of Queensland. This project was funded by the Department of Anaesthesia, Princess Alexandra Hospital. The Heart Lung Machine was supplied by the Brisbane Perfusion Services.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ottens J.. Education for the Australian and New Zealand perfusionist. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2003;35:4–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toomasian J, Searles B, Kurusz M.. The evolution of perfusion education in Americal. Perfusion. 2003;18:257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenkins OF, Morris R, Simpson J.. Australasian perfusion incident survey. Perfusion. 1997;12:279–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mejak B, Stammers A, Rauch E, Vang S, Viessman T.. A retrospective study on perfusion incidents and safety devices. Perfusion. 2000;15:51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stammers A, Mejak B.. An update on perfusion safety: does the type of perfusion practice affect the rate of incidents related to cardiopulmonary bypass. Perfusion. 2001;16:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palanzo DA.. Perfusion safety: Past, present and future. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1997;11:383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasmussen J.. The role of hierarchical knowledge representation in decision-making and system management. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cyber. 1985;15:234–43. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rasmussen J, Pejtersen A, Goodstein L.. Cognitive Systems Engineering. New York: Wiley and Sons; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vincente K.. Cognitive Work Analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum & Associates; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns CM, Hajdukiewicz JR.. Ecological Interface Design. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller A.. A work domain analysis framework for modelling intensive care unit patients. Cogn Tech Work. 2004;6:207–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hajdukiewicz JR, Vicente KJ, Doyle DJ, Milgram P, Burns CM.. Modeling a medical environment: an ontology for integrated medical informatics design. Int J Med Inform. 2001;62:79–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naikar N, Sanderson PM.. Work domain analysis for training-system definition and acquisition. Hum Fact. 2001;43:529–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reising DVC, Sanderson PM.. Minimal instrumentation may compromise failure diagnosis with an ecological interface. Hum Fact. 2004;46:316–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan PJ, Cleave-Hogg D.. A worldwide survey of the use of simulation in anesthesia. Can J Anaesth. 2002;49:659–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Runciman W, Sellen A, Webb R.. Errors, incidents and accidents in anaesthetic practice. Anaesth Inten Care. 1993;21:684–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper JB, Newbower RS, Long CD, Peek BM.. Preventable anesthesia mishaps: a study of human factors. Anesthesiology. 1978;49:399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millette G, Weerasena N, Cornel G, Broecker L.. A reusable training circuit for cardiopulmonary bypass. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2002;234:285–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morley PT, Walker T.. Australian Resuscitation Council: adult advanced life support (ALS) guidelines 2006. Crit Care Resusc. 2006;8:129–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holcomb HB, Stammers AH, Gao C, et al. Perfusion treatment algorithm: Methods of improving the quality of perfusion. J ECT. 2003;35:290–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shore-Lesserson L, Manspeizer HE, DePerio M, Vela-Cantos F, Ergin MA.. Thromboelastography-guided transfusion algorithm reduces transfusions in complex cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:312–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Despotis GJ, Grishaber JE, Goodnough LT.. The effect of an intraoperative treatment algorithm on physicians’ transfusion practice in cardiac surgery. Transf. 1995;34:290–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faulkner SC, Johnson CE, Tucker JL, Schmitz ML, Fasules JW, Drummond-Webb JJ.. Hemodynamic troubleshooting for mechanical malfunction of the extracorporeal membrane oxygenator systems using the PPP triad of variables. Perfusion. 2003;18:295–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Omodei M, Wearing A, McClennan J.. Head mounted video-recording: A method for studying naturalistic decision making. In: Flin R, Salas E, Strub M, Martin L, eds. Decision Making Under Stress. Burlington, VT: Ashgate; 1997;137–46. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Omodei MM, McLennan J, Wearing AJ.. How expertise is applied in real-world dynamic environments: Head-mounted video and cued recall as a methodology for studying routines of decision making. In: Betsch T, Haberstroh S, eds. The Routines of Decision Making. Mahwah, NJ: LEA; 2005;272–88. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill CE, O’Brien KM.. Helping Skills: Facilitating Exploration, Insight and Action. Washington, DC: American Psycholgical Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gottman JM, Roy AK.. Sequential Analysis: A Guide for Behavioural Researchers. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howell DC.. Statistical Methods for Psychology. 5th ed. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury; 2002. [Google Scholar]