Abstract:

Autologous platelet gel (APG) has become an expanding field for perfusionists. By mixing platelet-rich plasma (PRP) with thrombin and calcium, platelet gel is prepared and used in many surgical settings. There are many devices used to produce PRP. This study evaluates the Medtronic Magellan Autologous Platelet Separator. The purpose of this study was to show that processing two cycles of the same syringe could reduce the amount of blood required to produce a specific volume of PRP. Three 60-mL syringes of whole blood with anticoagulant were removed from 15 elective coronary artery bypass patients. Each syringe produced 9 mL of PRP and 1 mL was sent to the laboratory for analysis. The remaining whole blood in each syringe was processed a second time with a yield of 5 mL of PRP with 1 mL sent to the laboratory. With this data, the Magellan was assessed in three phases. The first phase focused on the consistency of the Magellan. Laboratory values of hematocrit, platelet count, white blood cell count, and fibrinogen were compared between each syringe processed by the device. The second phase dealt with the percentage of platelets in the PRP that the Magellan was able to capture. Finally, results of both cycles were combined and compared against baseline values. Most of the hematological factors evaluated between each syringe were consistent in both cycles. The Magellan was able to capture nearly 70% of all platelets in the PRP of the first cycle and 18.5% in the second cycle. By mathematically combining both cycles, platelet counts averaged 2.8 times baseline with a 3.3 times baseline increase when the volume of the two cycles was weighted. This weighted average was done to reflect a higher concentration of Cycle 1 platelets than Cycle 2 in each sample. This study proved that processing each syringe of whole blood twice could reduce blood requirements while maintaining an effective platelet yield and volume. It also showed that the Magellan does conform to benchmark testing done at Medtronic.

Keywords: platelet-rich plasma, Magellan, multiple cycles, blood conservation

Autologous platelet gel (APG) is a substance that is created by pheresis of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) from whole blood and combining it with thrombin and calcium. This “coagulum” has many advantages in a surgical setting. It contains higher amounts of fibrinogen, platelets, and growth factors than whole blood (1). The excess fibrinogen increases the strength and adhesive ability of the AGP, while native concentrations of fibrinogen lead to effective fibrinolysis and reabsorption of the gel (2). Platelet concentrations of two to four times baseline promote healing by exposing the site to an abundance of platelet derived growth factors (PDGFs) (3,4). APG has been shown to be beneficial in hemostasis when applied to surgical anastomosis and has proven to accelerate bone repair and growth during orthopedic and spinal surgery (5). APG has also shown promise in cardiac surgery, oral and maxillofacial surgery, and wound healing procedures (6–8). To use the benefits of APG, blood must be drawn from the patient. Using a table top autologous platelet separator, in this case the Medtronic Magellan (Minneapolis, MN), typical applications using APG require >150 mL of blood to be removed before surgery to produce a volume of APG suitable for the surgeons needs. According to test data reproduced at Medtronic, the use of the Magellan can harvest ∼70% of platelets in a 60-mL syringe of whole blood with one cycle per syringe. If this is true, processing each syringe a second time with 30% percent of the platelets and one half the volume of PRP as the first cycle could produce encouraging results. Being conscious of conserving blood, especially with high-risk surgical procedures, it is desirable to maximize the benefits of therapy while limiting the amount of donation required from the patient. This study intended to prove three things. First, the Magellan produces consistent results from one syringe to another. Second, the device can capture a high percentage of the platelets present in a syringe of whole blood. Finally, processing whole blood a second time with the Magellan can yield APG comparable with that produced with the first processing cycle. Hopefully, this could reduce the amount of blood required to be removed from the patient while still maintaining a quality product.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After institutional review board approval and patient consent, 15 patients undergoing elective coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) were included for this study. Patients were excluded based on the following: anti-platelet therapy (unless stopped 10 days before surgery); anemia; platelet count < 150 × 103/mm3; heparin therapy (unless discontinued 4 hours before surgery); fibrinolytic therapy (unless discontinued 48 hours before surgery); or redo-CABG procedure. Subsequently, patients who fit the criteria and were part of the study were treated with platelet gel.

Autologous blood was removed the morning of surgery by venipuncture or central line in the operating room. First, 9 mL of whole blood was collected for baseline analysis. Approximately 5.4 mL of whole blood was injected equally into two blue top vacuum tubes containing 0.109 mol/L, 3.2% sodium citrate. In addition, 3 mL was injected into lavender top vacuum tubes containing K2EDTA, 5.4 mg. Laboratory analysis for the following hematologic and coagulation parameters was measured: platelet count (PLT), hematocrit (HCT), white blood cell count (WBC), and fibrinogen (FIB). Baseline laboratory analysis could not be withdrawn from samples that contain the anticoagulant used, and therefore a hemodilution factor was used to calculate baseline platelet count, WBC, HCT, and FIB. After baseline samples were procured, whole blood was removed using three 60-mL syringes. Each syringe contained 8 mL of anticoagulant citrate dextrose (0.022 g/mL sodium citrate) before blood collection. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, a new autologous platelet separator kit was placed into the Magellan. The three syringes were processed to yield 10 mL of PRP, of which, 1 mL was sent to the laboratory for analysis. This analysis included HCT, WBC, PLT, and FIB. The remaining 9 mL of volume was used to treat these patients with platelet gel. This constituted the first cycle. After the first cycle was completed, a second disposable autologous platelet separator kit was placed into the Magellan. Each syringe was re-processed a second time to obtain 5 mL of PRP, and 1 mL was sent to the laboratory. This represents the second cycle. The remaining PRP sample was discarded.

Repeated-measures analysis of variance was conducted between each syringe of both cycles to verify the consistency of the Magellan product. The purpose of this was to look at the syringe collection difference on outcome (HCT, WBC, FIB, and PLT). A random subject effect was included in the model to show the correlation of measurements within the subjects. If an overall significant difference was found between each syringe, pairwise comparisons were made (comparing syringes 1 vs. 2, 1 vs. 3, and 2 vs. 3), and p values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Tukey method. Separate analyses were conducted for cycles 1 and 2. p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

To determine the percentage of platelets that the Magellan can capture per each syringe in each cycle, the following formulas were used. For the first cycle:

For the second cycle:

The final phase dealt with statistically incorporating the volume of two cycles and comparing them with baseline. Laboratory values of HCT, WBC, PLT, and FIB were compared by each cycle and by each syringe. PLT was analyzed by mathematically combining the products of both cycles and comparing them to baseline. A weighted average was calculated for each syringe. This was done to simulate the concentration of the volume that would be combined at the field. Because the first cycle of syringes produced twice the volume as the second, the weighted average was calculated as follows:

RESULTS

Results of the study were used to determine the statistical benefits of both cycles compared with each other and with baseline. Consistency between all of the syringes that were processed was also examined.

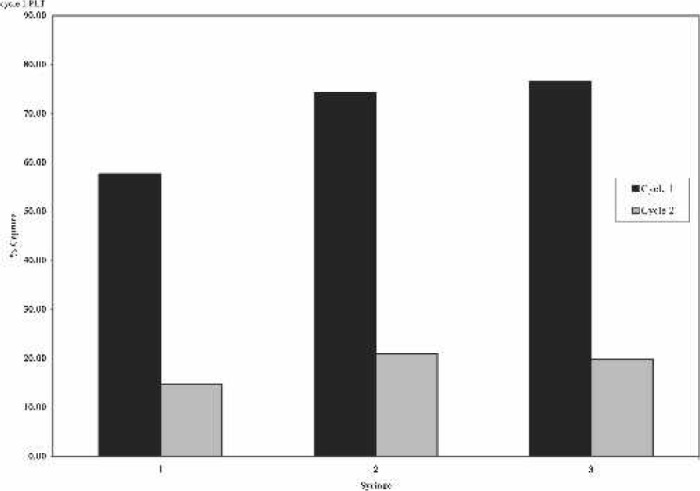

Platelet Counts

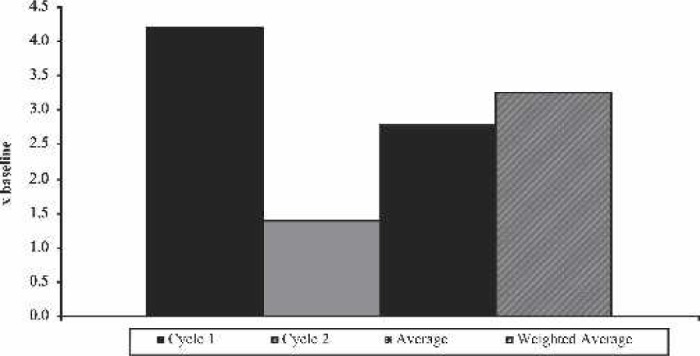

When analyzing each syringe for the first cycle, syringes 2 and 3 had significantly higher platelet counts than syringe 1 (p < .001 for both). There was no difference detected between syringes 2 and 3. With the second cycle, syringe 2 had significantly higher platelet counts than syringe 1 (p = .037). There was no difference detected between syringes 1 and 3 and 2 and 3 (Table 1). Platelet capture rates averaged 69.5% for the first cycle syringes. The range was between a mean of 57.6% on syringe 1 to a mean of 76.6% on syringe 3. In the second cycle, platelet capture rates averaged 18.5% with syringe 1 being the lowest at a mean of 14.7% and syringe 2 being the highest at 20.9% (Figure 1). Platelet counts in the first cycle averaged 4.2 times baseline. Platelet counts for the second syringe processed were consistently higher than the first or the third. The platelet counts for the second cycle averaged 1.4 times baseline. Similar to the first cycle, platelet counts for the second syringe processed were consistently higher than the first or the third. When the two samples were mathematically combined per syringe, they averaged 2.8 times baseline. The weighted average of both cycles showed an increase in the platelet count of 3.3 times baseline (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Comparison of outcomes by syringe collection.

| Outcome | Syringe Collection | Mean (SE) | Overall p Value |

Syringe 1 vs. 2 p Value |

Syringe 1 vs. 3 p Value |

Syringe 2 vs. 3 p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCT | Cycle 1 (1) | 4.50 (0.37) | .0062 | .98 | .011 | .018† |

| Cycle 1 (2) | 4.57 (0.37) | |||||

| Cycle 1 (3) | 5.59 (0.37) | |||||

| Cycle 2 (1) | 13.72 (1.09) | .22 | ||||

| Cycle 2 (2) | 14.33 (1.09) | |||||

| Cycle 2 (3) | 14.95 (1.09) | |||||

| WBC | Cycle 1 (1) | 8.33 (1.45) | .0039 | .13 | .0027* | .23 |

| Cycle 1 (2) | 9.35 (1.45) | |||||

| Cycle 1 (3) | 10.20 (1.45) | |||||

| Cycle 2 (1) | 8.78 (1.21) | .0036 | .0055* | .015* | .91 | |

| Cycle 2 (2) | 10.42 (1.21) | |||||

| Cycle 2 (3) | 10.22 (1.21) | |||||

| Fibrinogen | Cycle 1 (1) | 322.13 (16.2) | .052 | |||

| Cycle 1 (2) | 315.64 (16.2) | |||||

| Cycle 1 (3) | 315.42 (16.2) | |||||

| Cycle 2 (1) | 309.77 (16.0) | .43 | ||||

| Cycle 2 (2) | 314.37 (16.0) | |||||

| Cycle 2 (3) | 310.67 (16.0) | |||||

| Platelet count | Cycle 1 (1) | 529.87 (47.4) | .0001 | .0002* | .0001* | .96 |

| Cycle 1 (2) | 707.20 (47.4) | |||||

| Cycle 1 (3) | 717.27 (47.4) | |||||

| Cycle 2 (1) | 190.93 (15.6) | .037 | .032* | .20 | .63 | |

| Cycle 2 (2) | 234.20 (15.6) | |||||

| Cycle 2 (3) | 219.33 (15.6) |

Significantly higher than syringe 1.

Significantly higher than syringes 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Percent of platelet capture by syringe collection.

Figure 2.

Platelet count increase over baseline.

Fibrinogen Levels

Fibrinogen levels remained just above pre-processed averages. In both cycles, the fibrinogen levels were 2.2 times baseline. Fibrinogen levels were nearly equal between all of the syringes of both cycles without any statistical significance differences.

Hematocrit

On average, syringe 3 had a significantly higher HCT than syringes 1 and 2 (p = .011 and .018, respectively) in the first cycle. The second cycle results rendered no significant differences in HCT. The average HCT of the samples in the first cycle ranged from 4.5 to 5.6, with a mean of 4.9. The second cycle average HCT was at a much higher mean of 14.3, with a range of 13.72–14.95.

White Blood Cell Levels

In the first cycle results, syringe 3 has significantly higher WBC than syringe 1 (p = .0027). There was no difference between syringes 1 and 2 or between 2 and 3. Second cycle results showed that syringes 2 and 3 had significantly higher WBC than syringe 1 (p = .0055 and .015, respectively). There was no difference between syringes 2 and 3. WBC levels were consistently higher in all groups, ranging from 1.7 times baseline in the first cycle to 1.8 times in the second cycle.

DISCUSSION

APG has become a fast growing and exciting field for perfusionists and clinicians. The benefits of APG have proven valuable in many surgical fields and in wound healing (9,10). By using blood conservation strategies and by realizing the full potential of APG devices, it is possible to maximize the quality of platelet gel. To ensure confidence in the product that the Medtronic Magellan was producing, each syringe was compared with each other. PLT, HCT, and WBC levels tended to be significantly higher with syringe 3 and lowest with syringe 1. This was unusual because the trend was consistent for almost all of the patients and for both cycles even though the first blood syringe that was drawn from the patient was not always the first one processed. Fibrinogen levels remained consistent throughout the study at a little over twice baseline values for both cycles. This is important for the strength and adhesive ability of platelet gel (11). The HCT was significantly higher in the second cycle. It is believed that the device needed more of the red cell layer to capture the platelets in the second cycle. The WBC levels were nearly 1.8 times higher than baseline in both cycles. These increased WBC levels could prove to be helpful in fighting off infections, especially at surgical wound sites where platelet gel can be applied (12). With the knowledge that all platelet sequestering devices can only harvest a majority of the platelets, there is reason to believe that a significant amount of the platelets in a sample of whole blood are left uncollected. The Medtronic Magellan is no exception. It was our intention to prove that this was indeed true. By calculation, we were able to determine that nearly 70% of all platelets in a 60-mL syringe of whole blood were collected into a 10-mL volume of PRP. We also wanted to see if the second cycle could collect the remaining 30%. As it turns out, nearly 20% of the platelets were collected in a 5-mL sample of PRP. Blood conservation has and will always be a critical element of surgery. By limiting the amount of blood needed to collect for PRP, we can benefit the patient while limiting the risk. The essential question for this study is how many platelets in a sample of PRP are able to maximize the benefits of APG. Does a four-fold increase in the amount platelets over baseline produce a better quality of PRP than two or three times baseline? Is there a point at which the number of platelets in a sample of APG becomes negligible in its effectiveness? The purpose of this study was to show by numbers the effectiveness of maximizing resources. By processing each syringe twice and combining all the PRP volume produced, we were able to show a benefit in platelet yields from baseline while theoretically conserving the amount of blood that would be needed to be removed from the patient. In a multi-level spinal fusion that may require 60 mL of PRP, it would be possible to reduce the blood requirement by two whole syringes or 104 mL while still producing the same volume of PRP.

There are certain limitations to this study. They include a small sample size and a single surgical procedure. This is because of limited resources that were provided for the study. Also, a new Magellan Autologous Platelet Separator kit was opened between the first and second cycles for each patient. This was required because Medtronic has US Food and Drug Administration approval on processing three syringes per kit. Therefore, it was not possible to trial the second cycle syringes on the same kit as the first cycle. For this technique to be beneficial and cost effective, it would be advantageous if this platelet sequestering kit was able to be used for more than three syringes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Medtronic and the Mercy Medical Center–Sioux City Department of Laboratory for the generous donation of time and resources for this study and Trevor C. Huang, PhD, of Medtronic and Lynette Smith, MS, of University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Department of Preventative and Societal Medicine for statistical expertise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moro G, Casini V, Bastieri A.. Use of platelet-rich plasma in major maxillary sinus augmentation. Minerva Stomatol. 2003;52:267–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anitua E, Andia I, Ardanza B, et al. Autologous platelets as a source of proteins for healing and tissue regeneration. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson JL, Cupp CL, Ross EV, et al. The effects of autologous platelet gel on wound healing. Ear Nose Throat J. 2003;82:598–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhanot S, Alex JC.. Current applications of platelet gels in facial plastic surgery. Facial Plast Surg. 2002;18:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Floryan KM, Berghoff WJ.. Intraoperative use of autologous platelet-rich and platelet-poor plasma for orthopedic surgery patients. AORN J. 2004;80:668–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mogan C, Larson DF.. Rationale of platelet gel to augment adaptive remodeling of the injured heart. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2004;36: 191–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crovetti G, Martinelli G, Issi M, et al. Platelet gel for healing cutaneous chronic wounds. Transfus Apheresis Sci. 2004;30:145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lozada JR, Caplanis N, Proussaefs P, et al. Platelet rich plasma application in sinus graft surgery: Part I—background and processing techniques. J Oral Implantol. 2001;27:38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babbush CA, Kevy SV, Jacobson MS.. An in vitro and in vivo evaluation of autologous platelet concentrate in oral reconstruction. Implant Dent. 2003;12:24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slater M, Patava J, Kingham K, Mason RS.. Involvement of platelets in stimulating osteogenic activity. J Orthop Res. 1995;13:655–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seibert JS, Salama H.. Alveolar ridge preservation and reconstruction. Periodontol 2000. 1996;11:69–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stienhour EM, Riley JB, Tallman R, et al. Bacteriostatic and bactericidal properties of platelet-rich plasma in an in-vitro pseudomonas model. J Extra Corpor Technol. (in press). [Google Scholar]