Abstract

The Nicotine Dependence in Teens (NDIT) study is a prospective cohort investigation of 1294 students recruited in 1999–2000 from all grade 7 classes in a convenience sample of 10 high schools in Montreal, Canada. Its primary objectives were to study the natural course and determinants of cigarette smoking and nicotine dependence in novice smokers. The main source of data was self-report questionnaires administered in class at school every 3 months from grade 7 to grade 11 (1999–2005), for a total of 20 survey cycles during high school education. Questionnaires were also completed after graduation from high school in 2007–08 and 2011–12 (survey cycles 21 and 22, respectively) when participants were aged 20 and 24 years on average, respectively. In addition to its primary objectives, NDIT has embedded studies on obesity, blood pressure, physical activity, team sports, sedentary behaviour, diet, genetics, alcohol use, use of illicit drugs, second-hand smoke, gambling, sleep and mental health. Results to date are described in 58 publications, 20 manuscripts in preparation, 13 MSc and PhD theses and 111 conference presentations. Access to NDIT data is open to university-appointed or affiliated investigators and to masters, doctoral and postdoctoral students, through their primary supervisor (www.nditstudy.ca).

Key Messages.

Smoking onset trajectories among novice smokers included a low-intensity, non-progressing pattern (72% of novice smokers), and slow, moderate, and rapid escalating patterns (11%, 11%, and 6%, respectively). Escalating patterns were associated with earlier development of nicotine dependence.

Despite low cigarette exposure, 17% of novice smokers were tobacco dependent. More specifically 0%, 3%, 5%, 19% and 66% of triers, sporadic smokers, monthly smokers, weekly smokers and daily smokers, respectively, were dependent.

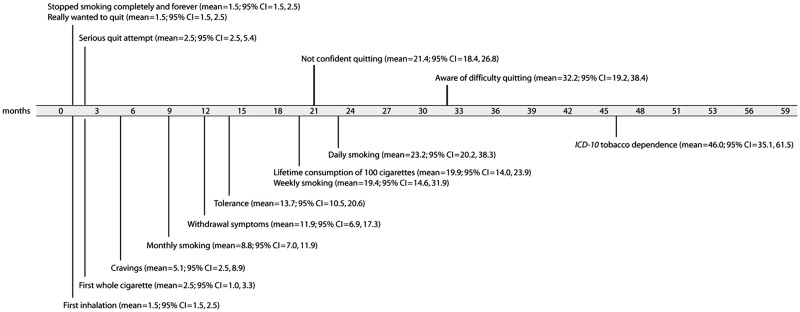

A mapping of the natural course of key milestones related to smoking onset showed that craving can emerge as early as 4 months after first puff. Whereas attempts to quit can begin soon after onset, novice smokers progressed through several stages in their perception of the difficulty quitting. There appears to be an important disconnect between expressed confidence in quitting and the ability to do so.

Of novice smokers, 40% discontinued smoking during the 5-year follow-up. Male sex, older age, believing cigarette package warnings, participating in team sports, low family stress, not being overweight, not being worried about weight, not using illicit drugs, and low level of craving for cigarettes were positively associated with smoking discontinuation.

Why was the cohort set up?

Smoking remains the most important preventable cause of death and disability in most developed countries. In Canada, 37 000 deaths each year1 and 21% of all deaths over the past decade are attributable to smoking.2 Despite widespread prevention programmes, explicit health warnings, anti-smoking legislation and declines in the social acceptability of smoking, far too many youth try smoking and continue to smoke into adulthood. Until recently, prevailing models of smoking behaviour postulated that nicotine dependence (ND) developed only after several years of regular smoking.3 However, numerous reports over the past decade suggest that many young smokers develop ND symptoms such as craving and withdrawal symptoms early in the smoking onset process, even when smoking is sporadic and infrequent.4–9 This has raised concerns that ND might in fact contribute to sustained smoking in novice smokers.10–12

The Nicotine Dependence in Teens (NDIT) study is a prospective cohort investigation of adolescents conducted in Montreal, Quebec (Canada). The project began in 1999 and the most recent data collection was completed in 2011–12. NDIT aimed to describe the natural course of cigarette smoking and ND in novice smokers, to measure the intensity of ND symptoms in relation to cigarette smoking and to investigate the importance of a wide range of individual-level and contextual factors in the initiation of smoking and ND. In addition to its primary objectives, NDIT has embedded studies on obesity, blood pressure, physical activity, team sports, sedentary behaviour, diet, genetics, alcohol use, use of illicit drugs, second-hand smoke, gambling, sleep and mental health.

NDIT has been supported financially by the Canadian Cancer Society since its inception in 1999. It was funded initially for 3 years and to date has received two renewals—one in 2002–05 and the other in 2006–13. The study received ethics approval from the Montreal Department of Public Health Ethics Review Committee, the McGill University Faculty of Medicine Institutional Review Board, the Ethics Research Committee of the Centre de Recherche du Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal and the University of Toronto.

Who is in the cohort?

NDIT used a school-based sampling strategy to identify and recruit participants. High schools (n = 13) in or near Montreal were selected in consultation with local school boards and school principals to include a mix of: (i) French- and English-language schools; (ii) urban, suburban, and rural schools; and (iii) schools located in high, moderate and low socioeconomic status neighbourhoods. In addition, all schools purportedly had relatively low in- and out-migration of students. Private schools were excluded. School administrators from all 13 schools approached agreed to participate; two schools were excluded because of a low return of parental consent forms, and one school was excluded because school administrators could not guarantee continued participation after the first year of the study. The total number of schools retained was 10.

All grade 7 students (mean age 12.8 years)in the study schools, including special needs students, were given a take-home information package that included a letter addressed personally to them and their parents or legal guardians describing the study, and a consent form for their parents or legal guardians to sign. This was followed by a presentation from the principal investigator in each school, which included a question-and-answer session for teachers and students. A total of 1294 of 2325 eligible students (56%), referred to herein as ‘NDIT participants’, participated in the baseline data collection. The relatively low response was related in part to the need for blood samples for genetic analysis, and to a labour dispute in Quebec that resulted in several teachers refusing to collect consent forms. No data were collected from non-respondents at baseline. Table 1 compares the baseline characteristics of NDIT participants with those of a provincially representative sample of youth aged 13 years in 1999 from the Quebec Child and Adolescent Health and Social Survey.13 The discrepancies in the indicators of cigarette smoking are likely to be explained to a large extent by the differences across samples in language spoken at home (the prevalence of smoking among Francophones is higher than in other language groups)14–16 and parent educational attainment.17,18

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics of NDIT participants with those of a provincially representative sample of Quebec youth aged 13 years, NDIT 1999–2000; Quebec Child and Adolescent Health and Social Survey (QCAHSS) 1999

| Characteristic | NDIT (n = 1294) | QCAHSS (n = 1186)a |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years (SD) | 12.8 (0.6) | 12.9 (0.3) |

| Male, % | 48 | 50 |

| French spoken at home, % | 30 | 85 |

| Born in Canada, % | 92 | 95 |

| Caucasian, % | 82 | 100b |

| Parent(s) university educated, % | 58 | 30 |

| Ever smoked, even just a puff, % | 32 | 53 |

| Smoked ≥100 cigarettes lifetime (among smokers), % | 27 | 37 |

| No. cigarettes/week (among past-week smokers), mean (SD) | 17.5 (24.3) | 20.9 (25.8) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 20.1 (3.8) | 20.6 (4.1) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean mmHg (SD) | 105.3(10.2) | 112.5 (11.8) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean mmHg (SD) | 56.6 (6.2) | 59.2 (7.0) |

| No. physical activities/week,c mean (SD) | 8.4 (8.6) | 8.0 (7.8) |

| TV viewing (h/week), mean (SD) | 20.5 (14.7) | 24.7 (14.1) |

| Drank alcohol,d % | 44 | 51 |

aIncludes children age 13years.

bNon-Caucasians were excluded by design.

cExcludes physical education classes at school.

dTime frame was past 3 months in NDIT and past 12 months in QCAHSS.

How often have they been followed up?

NDIT data collection included self-report questionnaires completed by NDIT participants, parents and school administrators, collection of blood and/or saliva samples from NDIT participants and their parents for deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) extraction, and direct observations on tolerance to smoking in school neighbourhoods (i.e. environmental scans). In addition, in selected survey cycles, NDIT participants completed anthropometric and blood pressure measurements and food frequency questionnaires and they wore accelerometers for the collection of objective measures of physical activity. Table 2 describes the chronology of the data collected according to survey cycle and/or year as well as the number of students, parents and school administrators who provided data.

Table 2.

NDIT data collection chronology

| Survey cycle | Grade (year) | Completed questionnaire (n) % of 1294 | Other measures | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 (1999–2000) | (1267) 98 | 1195 NDIT participants provided anthropometric and blood pressure measures | |

| 2 | (1198) 93 | 27 NDIT participants joined study after survey cycle 1 | ||

| 3 | (1191) 92 | |||

| 4 | (545) 42 | 6 schools not surveyed | ||

| 5 | 8 (2000–01) | (1104) 85 | ||

| 6 | (1101) 85 | |||

| 7 | (960) 74 | 1 school not surveyed | ||

| 8 | (982) 76 | 1 school not surveyed | ||

| 9 | 9 (2001–02) | (1022) 79 | ||

| 10 | (995) 77 | |||

| 11 | (972) 75 | 523 blood samples collected | ||

| 12 | (987) 76 | 955 NDIT participants provided anthropometric and blood pressure measures; 10 ‘School Questionnaires’ completed by school administrators and/or teachers | ||

| 13 | 10 (2002–03) | (914) 71 | ||

| 14 | (906) 70 | |||

| 15 | (904) 70 | |||

| 16 | (887) 69 | 171 Environmental Scans completed | ||

| 17 | 11 (2003–04) | (871) 67 | ||

| 18 | (853) 66 | |||

| 19 | (844) 65 | 804 NDIT participants provided anthropometric and blood pressure measures | ||

| 20 | (840) 65 | 84 NDIT participants refused follow-up before survey cycle 21; 1 NDIT participant died | ||

| 21 | 3 years post high school (2007–08) | (880) 68 | 336 NDIT participants provided saliva samples | 136 NDIT participants refused follow-up |

| Parent questio-nnaires | 2009–10 | — | 597 mothers completed Mother Questionnaire; 479 fathers completed Father Questionnaire; 648 mothers/fathers completed Questionnaire about NDIT Participant; 822 parents provided saliva samples | 14 NDIT participants refused follow-up |

| 22 | 6 years post high school (2011–12) | (858) 66 | 103 NDIT participants provided saliva samples; 363 NDIT participants completed Diet History Questionnaire; 781 NDIT participants provided anthropometric and blood pressure measures; 341 NDIT participants wore accelerometers; saliva samples for cotinine collected from 236 NDIT participants who smoked | 12 NDIT participants refused follow-up; 6 NDIT participants reintegrated into NDIT |

To minimize loss-to-follow-up, the NDIT team maintained frequent personalized contact with NDIT participants (particularly post high school, when data collections were less frequent) through telephone calls to verify contact information, newsletters highlighting NDIT results, e-mails and holiday cards. NDIT participants helped create the study name and logo, designed an NDIT t-shirt and were each given an NDIT t-shirt. Post high school, NDIT participants were offered monetary compensation for their time and involvement in the study.

Known reasons for refusal to continue in NDIT included moving to a non-participating school (during high school), lack of time and no longer any interest in the study. There are currently 1053 NDIT participants (81% of 1294) eligible for continued participation in NDIT. Table 3 compares the characteristics of these NDIT participants with the 241 who refused to continue follow-up at some point during the 13-year follow-up.

Table 3.

Comparison of baseline characteristics of NDIT participants who remained eligible to participate in NDIT with those of participants who refused to continue to participate at some point during follow-up. NDIT 1999–2013

| Characteristic | Eligible (n = 1053) | Refused (n = 241) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years (SD) | 12.7 (0.5) | 12.8 (0.6) |

| Male, % | 49 | 51 |

| French spoken at home, % | 30 | 29 |

| Born in Canada, % | 92 | 93 |

| Caucasian, % | 81 | 100 |

| Parent(s) university educated, % | 58 | 54 |

| Ever smoked, even just a puff % | 31 | 39 |

| No. cigarettes in past 3 months, mean (SD) | 8.0 (47.6) | 20.4 (101.3) |

| Overweight, % | 24 | 25 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 20.1 (3.9) | 20.1 (3.8) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean mmHg (SD) | 105.2 (9.8) | 105.7 (11.9) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean mmHg (SD) | 56.4 (6.1) | 57.6 (6.9) |

| Light physical activity, mean number of boutsa (SD) | 3.6 (3.1) | 3.1 (3.1) |

| Moderate physical activity, mean number of boutsa (SD) | 11.1 (10.3) | 9.9 (11.3) |

| Vigorous physical activity, mean number of boutsa (SD) | 3.8 (4.9) | 3.7 (5.8) |

| Team sports participation at school, % | 23 | 18 |

| Team sports participation outside school, % | 62 | 53 |

| Drinks alcohol, % | 42 | 49 |

| Depression score, mean (SD) | 2.1 (0.6) | 2.1 (0.6) |

aFor each activity, the participant reported the number of days per week (1–7) on which he/she participated in that activity for 5 minutes or more at one time. "Number of bouts" was the total number of days across all activities.

What has been measured?

Appendix 1 (available as Supplementary data at IJE online) provides a detailed description of all study variables including the items used to measure the variable, the response choices and the survey cycles in which data on the variable were collected. The paragraphs below provide an overview of data collection among NDIT participants and their parents, as well as the environmental scan.

NDIT participants

Baseline self-report questionnaires were completed during class time at school in autumn 1999 in nine schools and in autumn 2000 in one school. Follow-up questionnaires were completed every 3 months thereafter during the 10-month school year for the next 5 years (1999–2005) until NDIT participants completed grade 11 and graduated from high school, for a total of 20 survey cycles during high school. In 2007–08, when NDIT participants were age 20 years on average, they completed self-report questionnaires that were mailed to their homes with a stamped addressed return envelope (i.e. survey cycle 21). Finally, NDIT participants completed a self-report questionnaire administered in the NDIT research offices in 2011–12 when they were age 24 years on average (i.e. survey cycle 22).

The questionnaires covered a wide range of characteristics including: demographic characteristics; academic performance; psychosocial variables; indicators of smoking in the social environment; psychological variables; physical and mental health-related variables; weight-related characteristics; cigarette smoking; nicotine dependence; substance use; other lifestyle-related variables; and school and neighbourhood smoking context.

Trained technicians used standardized methods to measure height, weight, waist circumference, triceps and subscapular skinfold thickness19 and blood pressure20,21 at baseline and in survey cycles 12, 19 and 22. Repeat anthropometric measures were obtained in each of these survey cycles, in a systematic 1 in 10 subsample of NDIT participants. The inter-rater reliability coefficients (i.e. split-half coefficients) for measurements of height, weight and triceps skinfold thickness were 0.99, 0.99 and 0.97, respectively.

In survey cycle 22, in addition to self-report questionnaires and anthropometric and blood pressure measurements, an objective measure of physical activity (i.e. 7-day accelerometry) was obtained (n = 341), the Diet History Questionnaire22 was administered (n = 363) and saliva samples for cotinine were collected from 236 smokers.

Blood for DNA extraction was drawn in survey cycle 11 in 2002; 561 of 1054 NDIT participants (53%) had written parental consent for the blood draw, and blood specimens were obtained from 523 (50%of 1054). In 2007–08 and again in 2011–12 (i.e. survey cycles 21 and 22), saliva samples for DNA extraction were collected using ORAGENE kits (DNA Genotek, Kanata, ON, Canada) from NDIT participants who had not previously provided blood or saliva. An additional 439 NDIT participants provided saliva samples, for a total of 962 NDIT participants (74% of 1294) with either a blood or a saliva sample for DNA analyses.

Candidate gene genotyping approaches were used to assess genetic predictors of a selection of cigarette smoking and nicotine dependence phenotypes. Genotyping for CYP2A6, the gene encoding the principal nicotine metabolizing enzyme, was performed for five variant alleles using established methods based on gene- and allele-specific two-step polymerase chain reaction assays.23–25 The variants investigated [i.e. two partially inactive variants (CYP2A6*9, *12), two fully inactive variants (CYP2A6*2, *4) and the increased activity gene duplication, CYP2A6*1X2] were selected based on their impact on nicotine metabolism and on reported frequency in Caucasian populations.23

Selected based on a literature review including genome-wide association studies, 25 other genes possibly related to smoking phenotypeswere also genotyped. A greedy pairwise tagging approach,26 as implemented in the software Haploview,27 was used to tag polymorphisms in these genes using the International HapMap Project CEU data.28 An additional 36 candidate single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in these genes identified in the literature were also genotyped. All SNPs had a minor allele frequency >2.5% in the HapMap CEU population. The linkage disequilibrium cut-off was r2 = 0.8. Polymorphisms from 10 kb upstream to 10 kb downstream of each gene were tagged using genomic positions according to NCBI build 36. Sequenom iPlex Gold technology (Sequenom, San Diego, CA) was used for genotyping. The sample and SNP call rate thresholds were 95% and 80%, respectively. Overall genotyping reproducibility was >99.8%. A total of 398 SNPs from 25 genes were genotyped. In addition to SNPs possibly related to cigarette smoking, 46 SNPs (one per gene) purportedly associated with body weight were genotyped. Appendix 2 (available as Supplementary data at IJE online) lists all the SNPs genotyped to date in NDIT.

Parents of NDIT participants

Data were collected once from the parents of NDIT participants, in 2009–10. A package was mailed to the parents’/legal guardians’ home address with a stamped, addressed return envelope and included an explanatory letter, a self-report questionnaire for the biological mother or the person most like a mother to the participant (n = 597), a self-report questionnaire for the biological father or the person most like a father (n = 479) and a questionnaire completed by either parent that collected data about the NDIT participant (n = 648). In addition, the package included ORAGENE kits for both biological parents, and saliva samples for DNA extraction were obtained from 822 parents.

Environmental scan

In spring 2002, school-specific data on tobacco control policies and within-school activities promoting non-smoking were collected in questionnaires completed by school administrators and/or teachers in each school. In addition, a convenience sample of students and teachers was asked informally to identify commercial establishments (i.e. convenience stores, petrol stations, pharmacies, restaurants, fast -ood chains, grocery stores and discount stores) within a 1-mile (1.6-km) radius of schools where students ‘’hung out’’ before school, during breaks and lunch and after school. In 2003 each establishment was visited by two trained observers iwho collected data through direct observation on the availability of and access to tobacco products, visibility of no-smoking signs, and cigarette promotions, using an adapted assessment tool.29,30

What has NDIT found?

Among the more important NDIT contributions to date are that novice smokers can be categorized according to four patterns of progression in terms of cigarette use including low-intensity, non-progressing smokers (72%), and slow, moderate, and rapid escalators (11%, 11% and 6%, respectively).31 Escalating trajectory patterns were associated with earlier development of nicotine dependence and tolerance. Novice smokers who escalate rapidly should be targeted for early intense intervention to prevent development of nicotine dependence and sustained smoking.

Predictors of smoking initiation among never smokers in NDIT included both individual-level (i.e. younger age, single-parent family status, stress, impulsivity, low self-esteem, feeling a need to smoke, not doing well at school, susceptibility to tobacco advertising, alcohol use, use of other tobacco products) and contextual (i.e. smoking by parents, siblings, friends and school staff, attending a smoking-tolerant school) factors.32 One-dimensional prevention efforts that focus on single risk factors are unlikely to be effective in the long term. To improve targeting of prevention efforts, we developed a seven-item, user-friendly prognostic tool based on these results, for use by health practitioners to identify adolescents at high risk of becoming daily smokers.33

Despite generally low cigarette use, 17% of novice smokers were tobacco dependent.34 The proportion increased from 0%, 3% and 5% among triers, sporadic smokers and monthly smokers, respectively, to 19% and 66% among weekly and daily smokers, respectively. ND symptoms, including craving, distinguished each smoking category from less frequent smokers—challenging current smoking onset models which suggest that ND develops only after several years of regular heavy or daily smoking.

We mapped out, for the first time, the natural course of key milestones related to cigarette use, nicotine dependence and cessation among adolescent smokers (Figure 1).35,36 Craving can emerge as early as 4 months after first puff. Whereas the desire and attempts to quit can begin soon after smoking onset, novice smokers progressed through several stages in their perception of the difficulty of quitting, such that there appears to be an important disconnect between expressed confidence in quitting and the ability to do so. Overall these data suggest that novice smokers (and others) should be made aware that a first puff can represent the beginning of a process that leads rapidly to escalating cigarette use, emergence of nicotine dependence symptoms, and loss of control over smoking.

Figure 1.

Number of months after initiation at which the probability of attaining each milestone was 25%: Nicotine Dependence in Teens Study, 1999–2005.36 Note: Original figure published in: O'Loughlin J, Gervais A, Dugas E, Meshefedjian G. Milestones in the Process of Cessation Among Novice Adolescent Smokers, Am J Public Health, 99(3):499–504, 2009, The Sheridan Press (Figure 2 (page 503)).36

We studied the rate of occurrence of cigarette smoking initiation during early adulthood. 37 Of the 1294 NDIT participants, 75% had initiated smoking by age 24. Of those who initiated, 44% initiated before grade 7; 43% initiated during high school; and 14% initiated after high school. Determinants of smoking initiation in young adults included alcohol use, higher impulsivity and poor academic performance.

In a study on the association between cigarette smoking and anthropometric measures in novice smokers, a 100-cigarette/month increment in cigarette use over 2.5 years in boys was associated with lower body mass index and shorter height.38 In girls, cigarette use was not associated with height or adiposity. Young girls may be less likely to take up cigarette smoking if tobacco control messages emphasize that cigarette use may not be associated with reduced weight in adolescent females.

We also used NDIT data to assess associations between genetically variable nicotine metabolism rates (via CYP2A6 polymorphisms) and smoking behaviours. Relative to adolescents with faster CYP2A6 nicotine metabolism, slower CYP2A6 nicotine metabolizers displayed a higher risk and rate of nicotine dependence acquisition,39–41,42 but lower cigarette consumption,39 slower progression in nicotine dependence41 and an increased likelihood of quitting smoking.42

We identified determinants of smoking discontinuation, a novel cessation phenotype relevant to novice smokers who may not yet recognize themselves as being smokers.43 Of 620 novice smokers, 40% discontinued smoking during high school. Male sex, increased age, cigarette package warnings and team sports were positively associated and family stress, worry about weight, overweight, illicit drug use and craving were negatively associated with discontinuation. Several of these determinants could be targeted to increase the effectiveness of youth cessation programmes.

Finally, the collection of data on obesity, blood pressure, physical activity, team sports, sedentary behaviour, diet, genetics, alcohol use, use of illicit drugs, second-hand smoke, gambling, sleep and mental health have allowed the exploration of many novel hypotheses related to the childhood origins of the risk of adult chronic disease. The list of all NDIT publications can be found at www.nditstudy.ca

What are the main strengths and weaknesses of NDIT?

The main strengths of NDIT include its longitudinal design with frequent data collection during high school, long-term follow-up of participants from age 12 to 24 years and the wide range of diverse data available, from genetic material to measures of smoking tolerance in schools and school neighbourhoods. Despite a low baseline response rate, the follow-up rate was very good. Finally, NDIT brings together newly-trained and well-established researchers across a wide range of disciplines, all with an interest in youth. NDIT provides a rich platform for add-on studies and for developing capacity for interdisciplinary research among team members, students and collaborators.

Limitations include that use of self-report questionnaires may have led to some misclassification, and that losses-to-follow-up over time may have resulted in prospective selection bias. In particular, those lost to follow-up were heavier smokers.

Can I get a hold of the data? Where can I find out more?

Access to NDIT data is open to any university-appointed or affiliated investigator upon successful completion of the application process. Masters, doctoral and postdoctoral students may apply through their primary supervisor. To gain access, applicants must complete the ‘Request for NDIT Data/DNA Application Form’ and return it to the principal investigator (jennifer.oloughlin@umontreal.ca). Approval will be based on scientific merit, relevance and overlap with other projects. The outcome of the approval process, including conditions (i.e. adding investigators), recommendations (i.e. reorienting objectives) and/or reason(s) for rejection (e.g. overlap with other analyses), will be communicated by e-mail to applicants within 4–6 weeks of receipt of the application. For more information, visit www.nditstudy.ca or contact the principal investigator.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at IJE online.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Cancer Society (grants 010271 and 017435), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grants MOP86471 and TMH-109787), the Center for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), the CAMH foundation, the Canada Foundation for Innovation (grants 20289 and 16014) and the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation. J.O.L. holds a Canada Research Chair in the Early Determinants of Adult Chronic Disease. R.F.T. holds an Endowed Chair in Addictions in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto. I.K. is a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator.E.C. and N.A. hold career awards from the Fonds de Recherche Santé-Québec. J.B. and M.C. are supported by Canadian Cancer Society Career Development Awards in Prevention. G.C. is funded by the Fonds de Recherche Santé-Québec. A.V.H. received support from a CIHR/Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada Doctoral Training Grant in Population Intervention for Chronic Disease Prevention, and a doctoral scholarship from the Fonds de Recherche Santé-Québec. R.P. was a recipient of a CIHR doctoral training award and is currently a CIHR postdoctoral fellow. M.J.C. received a CIHR Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award and an Ontario Graduate Scholarship. E.O.L. is funded by the Fondation CHU Sainte-Justine. T.A.B. holds a salary award from the Fonds de Recherche Santé-Québec.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the NDIT participants, their parents, and the schools that participated in NDIT.

Conflicts of interest: R.F.T. has been a consultant to pharmaceutical companies, primarily on smoking cessation. A.G. was a paid consultant for Pfizer Canada’s Varenicline Advisory Board. The remaining authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Baliunas D, Patra J, Rehm J, Popova S, Kaiserman M, Taylor B. Smoking-attributable mortality and expected years of life lost in Canada 2002: conclusions for prevention and policy. Chronic Dis Can 2007;27:154–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones A, Gulbis A, Baker EH. Differences in tobacco use between Canada and the United States. Int J Public Health 2010;55:167–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health 3, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiFranza JR, Rigotti NA, McNeill AD, et al. Initial symptoms of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Tob Control 2000;9:313–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wellman RJ, DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Dussault GF. Short term patterns of early smoking acquisition. Tob Control 2004;13:251–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colby SM, Tiffany ST, Shiffman S, Niaura RS. Are adolescent smokers dependent on nicotine? A review of the evidence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2000; 59:83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prokhorov AV, Hudmon KS, Cinciripini PM, Marani S. ‘Withdrawal symptoms’ in adolescents: a comparison of former smokers and never-smokers. Nicotine Tob Res 2005;7:909–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rojas NL, Killen JD, Haydel KF, Robinson TN. Nicotine dependence among adolescent smokers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1998;152:151–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Killen JD, Ammerman S, Rojas N, Varady J, Haydel F, Robinson TN. Do adolescent smokers experience withdrawal effects when deprived of nicotine? Exp Clin Psychopharm 2001;9:176–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Rigotti NA, et al. Development of symptoms of tobacco dependence in youths: 30 month follow up data from the DANDY study. Tob Control 2002;11:228–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, et al. Symptoms of tobacco dependence after brief intermittent use: the Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youth-2 study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007;161:704–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dierker L, Mermelstein R. Early emerging nicotine-dependence symptoms: a signal of propensity for chronic smoking behavior in adolescents. J Pediatr 2010;156:818–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paradis G, Lambert M, O’Loughlin J, et al. The Québec Child and Adolescent Health and Social Survey: design and methods of a cardiovascular risk factor survey for youth. Can J Cardiol 2003;19:523–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeWit DJ, Beneteau B. Predictors of the prevalence of tobacco use among Francophones and Anglophones in the province of Ontario. Health Educ Res 1999;14:209–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wharry S. Canada a country of two solitudes when smoking rates among anglophones, francophones compared. CMAJ 1997;156:244–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Loughlin J, Maximova K, Tan Y, Gray-Donald K. Lifestyle risk factors for chronic disease across family origin among adults in multiethnic, low-income, urban neighborhoods. Ethn Dis 2007;17:657–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, Fidler JA, Munafò M. Socioeconomic status and smoking: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012;1248:107–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harwood GA, Salsberry P, Ferketich AK, Wewers ME. Cigarette smoking, socioeconomic status, and psychosocial factors: examining a conceptual framework. Public Health Nurs 2007;24:361–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evers SE, Hooper MD. Dietary intake and anthropometric status of 7 to 9 year old children in economically disadvantaged communities in Ontario. J Am Coll Nutr 1995;14:595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park MK, Menard SM. Accuracy of blood pressure measurement by the Dinamap monitor in infants and children. Pediatrics 1998;8:308–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luepker RV, Perry CL, McKinlay SM, et al. Outcomes of a field trial to improve children’s dietary patterns and physical activity. JAMA 1996;275:768–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Csizmadi I, Kahle L, Ullman R, et al. Adaptation and evaluation of the National Cancer Institute's Diet History Questionnaire and nutrient database for Canadian populations. Public Health Nutr 2007;10:88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu C, Goodz S, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF. CYP2A6 genetic variation and potential consequences. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2002;54:1245–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oscarson M, McLellan RA, Asp V, et al. Characterization of a novel CYP2A7/CYP2A6 hybrid allele (CYP2A6*12) that causes reduced CYP2A6 activity. Hum Mutat 2002;20:275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schoedel KA, Hoffmann EB, Rao Y, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF. Ethnic variation in CYP2A6 and association of genetically slow nicotine metabolism and smoking in adult Caucasians. Pharmacogenetics 2004;14:615–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Bakker PI, Yelensky R, Pe'er I, Gabriel SB, Daly MJ, Altshuler D. Efficiency and power in genetic association studies. Nat Genet 2005;37:1217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 2005;21:263–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.International HapMap Constortium. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature 2007;449:851–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Point-of-purchase tobacco environments and variation by store type – United States, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002;51:184–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frohlich KL, Potvin L, Gauvin L, Chabot P. Youth smoking initiation: disentangling context from composition. Health Place 2002;8:155–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karp I, O'Loughlin J, Paradis G, Hanley J, Difranza J. Smoking trajectories of adolescent novice smokers in a longitudinal study of tobacco use. Ann Epidemiol 2005;15:445–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Loughlin J, Karp I, Koulis T, Paradis G, DiFranza J. Determinants of first puff and daily cigarette smoking in adolescents. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170:585–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karp I, Paradis G, Lambert M, Dugas E, O'Loughlin J. A prognostic tool to identify adolescents at high risk of becoming daily smokers. BMC Pediatr 2011;11:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Loughlin J, DiFranza J, Tyndale RF, et al. Nicotine-dependence symptoms are associated with smoking frequency in adolescents. Am J Prev Med 2003;25:219–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gervais A, O'Loughlin J, Meshefedjian G, Bancej C, Tremblay M. Milestones in the natural course of onset of cigarette use among adolescents. CMAJ 2006;175:255–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Loughlin J, Gervais A, Dugas E, Meshefedjian G. Milestones in the process of cessation among novice adolescent smokers. Am J Public Health 2009;99:499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Loughlin JL, Dugas EN, O'Loughlin EK, Karp I, Sylvestre M-P. Incidence and determinants of cigarette smoking initiation in young adults. J Adolesc Health 2014;54:26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Loughlin J, Karp I, Henderson M, Gray-Donald K. Does cigarette use influence adiposity or height in adolescence? Ann Epidemiol 2008;18:395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Loughlin J, Paradis G, Kim W, et al. Genetically decreased CYP2A6 and the risk of tobacco dependence: a prospective study of novice smokers. Tob Control 2004;13:422–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karp I, O’Loughlin J, Hanley J, Tyndale RF, Paradis G. Risk factors for tobacco dependence in adolescent smokers. Tob Control 2006;15:199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al Koudsi N, O'Loughlin J, Rodriguez D, Audrain-McGovern J, Tyndale RF. The genetic aspects of nicotine metabolism and their impact on adolescent nicotine dependence. J Pediatr Biochem 2010;1:105–23. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chenoweth MJ, O’Loughlin J, Sylvestre M, Tyndale RF. CYP2A6 slow nicotine metabolism is associated with increased quitting by adolescent smokers. Pharmacogenetics 2013;23:232–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Loughlin J, Sylvestre MP, Dugas E, Karp I. Determinants of the occurrence of smoking discontinuation in novice adolescent smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014;23:1090–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.