Abstract

Introduction:

Clinical Dermatology is a visually oriented specialty, where visually oriented teaching is more important than it is in any other specialty. It is essential that students must have repeated exposure to common dermatological disorders in the limited hours of Dermatology clinical teaching.

Aim:

This study was conducted to assess the effect of clinical images based teaching as a supplement to the patient based clinical teaching in Dermatology, among final year MBBS students.

Methods:

A clinical batch comprising of 19 students was chosen for the study. Apart from the routine clinical teaching sessions, clinical images based teaching was conducted. This teaching method was evaluated using a retrospective pre-post questionnaire. Students’ performance was assessed using Photo Quiz and an Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE). Feedback about the addition of images based class was collected from students.

Results:

A significant improvement was observed in the self-assessment scores following images based teaching. Mean OSCE score was 6.26/10, and that of Photo Quiz was 13.6/20.

Conclusion:

This Images based Dermatology teaching has proven to be an excellent supplement to routine clinical cases based teaching.

Keywords: Clinical images based teaching, clinical teaching, dermatology, medical education

What was known?

Dermatology is visually oriented specialty

Clinical images are widely used to teach Dermatology

Only limited number of studies is available to prove its efficacy.

Introduction

The patients with skin diseases constitute nearly 10% of total outpatients department attendees in any tertiary care institute.[1,2] Identifying common skin diseases and providing appropriate referral service to patients in the community will be the role of any qualified medical undergraduate. However, the effectiveness of undergraduate Dermatology curriculum in achieving this objective is debatable. In India, time allocated for Dermatology teaching varies from 4 weeks to 6 weeks over a period of 3 years, which is inadequate and the effective use of the allocated time is also questionable. Hence, there is a compelling need to impart knowledge, skill, and attitude in this stipulated time. This requires innovation in clinical teaching methods and an extra effort from teachers. Though there is no replacement for clinical case-based teaching, addition of a “clinical images based module” is expected to be an innovative way to enhance the understanding and diagnostic skills of students, thus effectively utilizing the stipulated time.

Objectives

To assess the effect of clinical images based teaching as a supplement to patient based clinical teaching in Dermatology, among final year MBBS students

To create image-based clinical teaching module for undergraduate clinical teaching.

Methods

Creating clinical images based teaching module

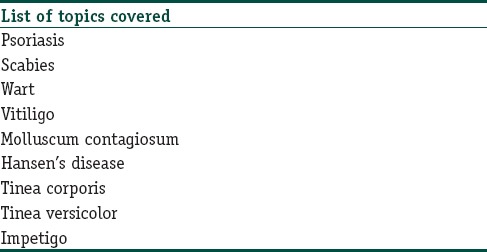

A team of four Dermatology teachers was formed for designing the module. A comprehensive list of all common dermatoses, an undergraduate, should learn during Dermatology clinical posting was made based on the curriculum given by Medical Council of India [Table 1].

Table 1.

List of topics taught during the posting

A clinical images based module was prepared for each topic keeping in mind the following clinical aspects

Most common presentation

Varied presentations

Other morphological types

Pattern and distribution of lesions

Differential diagnosis.

Good quality images (300 dpi) of standard size were chosen from the image bank of Department of Dermatology, to create a module

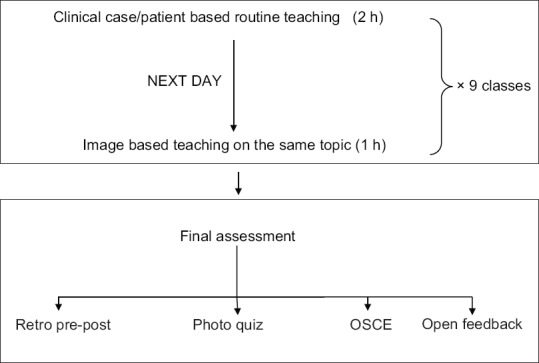

Implementing the module

A clinical batch comprising of 19 students was enrolled for this education interventional study and they were explained clearly about the clinical images module. The study was reviewed by Medical Education Unit of Our Institute. During their clinical posting, the eighth-semester students had usual 2 h of clinical case-based teaching. The following day images based teaching on the same topic was conducted for the first 1 h, during which images were shown without any descriptors and students were allowed to identify and describe the lesions. If they were unable to describe or identify lesions, further detailing was given to them. This order was followed to avoid bias due to prior information they had obtained and to allow adequate time for recollection of information from the previous day's clinical class.

Assessment of students and evaluation of the module

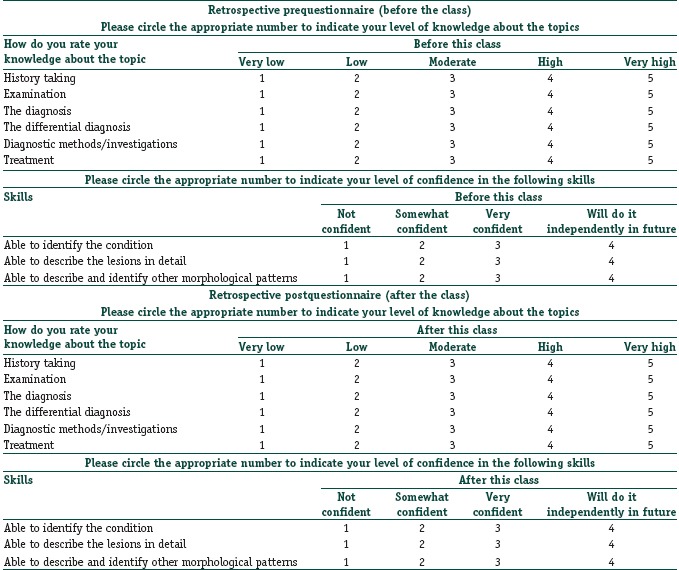

Self-assessment using retrospective pre-post questionnaire:

Students were asked to fill in a questionnaire after the class, to rate their knowledge and skill before class and after class.[3] The questionnaire had two parts as, assessing their knowledge and skill. The parameters rated were their knowledge about history taking, examination, differential diagnosis, investigations, and treatment for the condition, and their skill in identification and description of the lesions. Their current level of knowledge and skills were rated on a five-point and four-point Likert scale, respectively [Annexure I]. Open feedbacks were collected from students and examiners.

Annexure 1:

Objective assessment test

Photo quiz was conducted to assess their ability to identify the lesion and describe the lesion. Objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) was used for the assessment of their knowledge and skill [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Study design

Statistical analysis

Self-assessment scores before and after the intervention were compared using Wilcoxon-sign rank test. Means and standard deviations were calculated using Student's t-test. Statistical tests were done using Epi Info™ 7.

Results

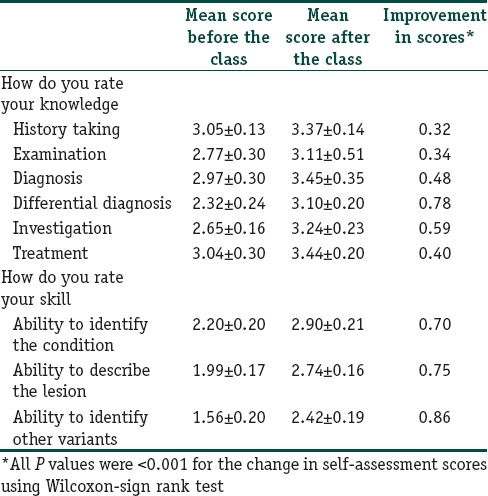

The mean percentage of attendance recorded was 89.73%. Thirteen out of 19 subjects had attended all the classes. The evaluation of this teaching method using retrospective pre-post questionnaire method of self-assessment showed a significant improvement of knowledge and skills after images based teaching. The Cronbach alpha coefficient, which is the measure of internal consistency of items used in the questionnaire, was 0.67 which is considered acceptable. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed that the images based clinical classes had elicited a statistically significant change in the self-assessment scores (P < 0.05) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Mean scores of self-assessment before and after images based teaching on nine topics covered

Objective assessment using photo quiz had a mean score of 13.6 out of 20 while the OSCE score was 6.26 out of 10. All subjects gave a positive feedback about this combined method of teaching.

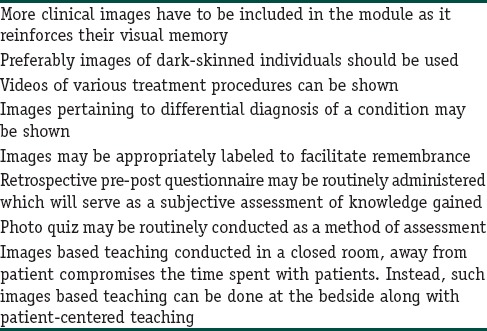

The examiner who assessed the subjects gave a positive feedback as well. The examiner was able to perceive a significant improvement in the performance of students in the OSCE conducted at the end of the clinical posting. Most of them were able to give a complete description of the skin lesions and were easily able to identify various morphological patterns of a particular disease. Students gave some suggestions about the teaching method during the feedback session, which are listed in [Table 3].

Table 3.

Feedback suggestions given by students

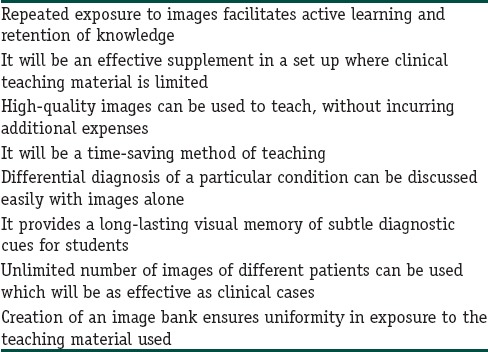

Discussion

Dermatology is a visually oriented subject. Clinical diagnosis in Dermatology primarily depends on the inspection findings in most cases. Hence, the clinical images can serve as a valuable teaching material. Further, the interpretation of skin diseases in the native skin color poses challenges to a beginner who is baffled by the variations in presentation. Repeated exposure to clinical images is expected to increase the diagnostic skills, as well.[4] Advantages are as listed in the [Table 4]. Most descriptions of Dermatological disorders that are described in the white skin have to be extrapolated in Indian skin. In this context, visual images of the disorders in the native population are very useful.

Table 4.

Advantages of clinical images based teaching

The enhancement of knowledge, clinical skill, and performance of the subjects was quite apparent from results of various feedback methods used in our study. We also could perceive a change in the learning behavior of the students who showed constant enthusiasm in learning throughout this method of teaching. No other study has used clinical images as a supplement to the conventional clinical teaching and studied their effect.

Teaching students in a clinical setup give them the opportunity to handle the clinical problem in a reality wherein all components described in Millers pyramid of assessment can be addressed.[5] This setup also addresses the affective domain of learning among students.

The traditional clinical teaching is not without challenges. Competing responsibilities of a clinician (to provide outpatient services, inpatient services and conducting classes), time limitation, lack of adequate clinical material, and the lack of adequate planning for teaching are some of the challenges a Dermatologist face in a teaching institute.[6] Noncooperation from patients is another problem often faced when a group of students examines them.

Aubrey et al. used interactive teaching mechanisms such as didactic lectures, preceptor-led live patient sessions, poster exhibit, and CD-ROM program composed of digital reproduction of Kodachrome slide images presented in lectures, to teach “Introduction of Dermatology” to 2nd year medical students. They found that among the teaching mechanisms, live patient session program, CD-ROM and poster exhibits (in decreasing order) generated highest ratings. In the feedback given by students, there had been a considerable number of requests for even greater access to virtual images of skin diseases.[7]

Freeman et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of digital Dermatology instructional program, wherein residents themselves displayed posters of the cases they encountered in their family medicine center and he observed that residents’ diagnostic skills improved over a period of time.[4]

The language of Dermatology created by Raugi GJ et al., consisted of a module for teaching basic lesions in Dermatology, a review atlas module and a self-assessment module for subjective feedback and examination. It was concluded that web-based approach to teach morphology presents a valuable tool for teaching Dermatology.[8]

Another study conducted by Jenkins et al., compared the effects of computer-assisted instruction (CAI) versus traditional lectures, and showed no statistically significant difference. The study only tested medical students on dermatology morphology visual recognition and appropriate the use of terminology which was only a small part of their overall course. Students were given a short time frame to recall the information. These were the possible reasons given by them for lack of significant difference between teaching methods.[9]

A study conducted by Kaliyadan on self-learning digital module which consisted of power-point presentations, instructive videos demonstrating signs in the dermatological examination, interactive quizzes and images to teach students, showed an overall positive feedback about the module.[10]

Chumley-Jones et al. in their review of the literature on CAI concluded that it can serve as a valuable addition to traditional methods such as text, lecture, and small group discussion or problem-based learning. It was also observed that learners welcome it and give high satisfaction ratings. However, there is no evidence that students learn more from such information technology compared to traditional teaching.[11] Berman et al. recommended the use of CAI preceding the didactic teaching or be used as a supplement to present a clinical scenario. He referred to it as “blended learning.”[12]

Farrimond et al. developed a structured computer-based skin examination module to teach step by step skin examination to medical students. The authors considered it as a part of the instructional sequence to teach Dermatology rather than a replacement for the traditional method.[13]

Most of the studies were done on the effect of self-learning modules. Compared to the teacher guided module (as we did), self-learning modules have several limitations such as social isolation, lack of individualized instruction, high development and maintenance costs, technical problems, and poor instruction design.[14] Moreover, such self-learning modules design largely depend on the self-learning tendency of learners, and it has not been adequately studied in comparison with that of traditional methods.[10]

Limitations

Our study did not compare the effect of combining the image-based method with traditional clinical teaching and that of a traditional method alone. The sample size is also less. The effectiveness of this combined method of teaching is evident from scores of Retrospective pre-post questionnaires which showed consistent improvement after the image based module, for all nine topics covered. We did not follow-up the candidates to assess the long-term retention of knowledge acquired during the clinical posting. Such image-based clinical teaching requires audio-visual aids and hence might compromise the time spent by the students with the patients. Those teachers who strongly adhere to traditional, patient-centered clinical teaching may resist such an innovation.

Conclusion

This modality of teaching has evolved over years with the addition of modern audio-visual aids, and it is in tune with the needs of modern day medical students. This “Images based Dermatology teaching module” has proven to be an excellent supplement to routine clinical cases based teaching. It helps to reinforce the classical clinical features and also the varied manifestations of a particular skin disease in the minds of students. The perceived change in the performance of students after this module affirms it.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

This images based Dermatology teaching has proven to be an excellent supplement to routine clinical cases based teaching

It helps to reinforce the classical clinical features and also the varied manifestations of a particular skin disease in the minds of students.

References

- 1.Asokan N, Prathap P, Ajithkumar K, Ambooken B, Binesh VG, George S. Pattern of skin diseases among patients attending a tertiary care teaching hospital in Kerala. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:517–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.55406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kataria U, Chillar D. Pattern of skin diseases among patients attending skin OPD of BPS GMC, khanpur kalan. Indian J Res Rep Med Sci. 2013;3:39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhanji F, Gottesman R, de Grave W, Steinert Y, Winer LR. The retrospective pre-post: A practical method to evaluate learning from an educational program. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:189–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fawcett RS, Widmaier EJ, Cavanaugh SH. Digital technology enhances Dermatology teaching in a family medicine residency. Fam Med. 2004;36:89–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wass V, Van der Vleuten C, Shatzer J, Jones R. Assessment of clinical competence. Lancet. 2001;357:945–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04221-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Islam MS, Khan I, Talukder HK, Akther N. Clinical teaching in dermatology of undergraduate medical students of Bangladesh. Bangladesh J Med Educ. 2010;01:16–24. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartmann AC, Cruz PD., Jr Interactive mechanisms for teaching dermatology to medical students. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:725–8. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.6.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raugi GJ, Kim S, Odland PB. Teaching morphology on the World Wide Web: The experience of “Language of dermatology”. Dermatol Online J. 1996;2:3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenkins S, Goel R, Morrell DS. Computer-assisted instruction versus traditional lecture for medical student teaching of dermatology morphology: A randomized control trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:255–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaliyadan F, Manoj J, Dharmaratnam AD, Sreekanth G. Self-learning digital modules in dermatology: A pilot study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:655–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chumley-Jones HS, Dobbie A, Alford CL. Web-based learning: Sound educational method or hype? A review of the evaluation literature. Acad Med. 2002;77(10 Suppl):S86–93. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200210001-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berman NB, Fall LH, Maloney CG, Levine DA. Computer-assisted instruction in clinical education: A roadmap to increasing CAI implementation. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2008;13:373–83. doi: 10.1007/s10459-006-9041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farrimond H, Dornan TL, Cockcroft A, Rhodes LE. Development and evaluation of an e-learning package for teaching skin examination. Action research. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:592–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva CS, Souza MB, Silva Filho RS, Medeiros LM, Criado PR. E-learning program for medical students in dermatology. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:619–22. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000400016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]