Abstract

Background:

Dermatologic conditions have different presentation and management in pediatric age group from that in adult; this to be studied separately for statistical and population based analysis.

Objective:

To study the pattern of various dermatoses in infants and children in tertiary health care center in South Gujarat region.

Materials and Methods:

This is a prospective study; various dermatoses were studied in pediatric patients up to 14 years of age attending the Dermatology OPD of New Civil Hospital, Surat, Gujarat over a period of 12 months from June 2009 to June 2010. All patients were divided into four different study groups: <1 month (neonates), 1 month to 1 year, >1 to 6 years and 7 to 14 years.

Results:

There were 596 boys and 425 girls in total 1021 study populations. Majority of the skin conditions in neonates were erythema toxicum neonatorum (12.97%), scabies (9.92%), mongolian spot (9.16%), and seborrheic dermatitis (7.63%). In > 1 month to 14 years age group of children among infectious disorder, children were found to be affected most by scabies (24.49%), impetigo (5.96%), pyoderma (5.62%), molluscum contagiosum (5.39%), tinea capitis (4.49%), leprosy (2.02%), and viral warts (1.35%) while among non-infectious disorders, they were affected by atopic dermatitis (4.27%), pityriasis alba (4.16%), seborrheic dermatitis (3.60%), pityriasis rosea (3.15%), others (3.01%), phrynoderma (2.70%), lichen planus (2.58%), contact dermatitis (1.57%) and ichthyosis (1.45%).

Conclusion:

There is a need to emphasize on training the management of common pediatric dermatoses to dermatologists, general practitioners and pediatricians for early treatment.

Keywords: Children, India, neonates, pediatric dermatoses, South Gujarat

What was known?

Infestation and infection was the most common dermatoses in pediatric age groups. The pattern of dermatoses in pediatric age group reflects economic, social and hygienic status of the community.

Introduction

Children cannot be simply considered as “small adult”. Due to anatomical differences, certain diseases occur in the childhood while many occur rarely at this time. Because of more delicate nature of the skin of infant and children as well as constant exposure to trauma, most skin diseases of childhood are attributable to physical causes, infections and allergy. Also, the disease pattern differs in a given population by different ecological factors.[1] The majority of dermatoses in newborns are physiological and transient, while genodermatoses or hereditary, congenital and nevoid anomalies which usually are first seen during childhood.[2]

Dermatologic conditions constitute at least 30% of all outpatient visits to pediatricians and 30% of all visits to dermatologists involve children.[3,4] The incidence of various dermatologic conditions varies according to age, race, geographic locations, climate, nutrition, hygiene, socio-economic conditions and heredity.[5,6,7,8] Several problems including lack of education, social backwardness, lack of health care facilities in the rural area, lack of sanitation, excess pollution and overcrowding contribute to more incidence of infectious disorders in developing countries like India.

The incidence of skin diseases among children in various parts of India has ranged from 8.7% to 38.8% in different studies usually school-based surveys.[9] Studies of pediatric population which constitutes the cornerstone of the community can play an important role in determining the policies of protective medicine and public health. The aim of this study is to give an overview of the statistical study of different dermatologic diseases in infant and children in tertiary care hospital in South Gujarat region.

Material and Methods

This is a prospective study of pediatric patients attending the Dermatology OPD of New Civil Hospital, Surat (NCHS), Gujarat over a period of 12 months from June 2009 to June 2010. NCHS is the main hospital in South Gujarat region and one of the tertiary health care center accessed by many patients in the region. It serves a population of approximately 2.4 millions. This ensures an input of a wide spectrum of diseases including complex problems to more commonly seen in primary health care centers by general practitioners. Consecutive 1021 pediatric patients up to 14 years of age were included into the study. Written consent was taken from the guardian of each patient enrolled into the study. All patients were divided into four different groups: <1 month (neonates), 1 month to 1 year, >1 to 6 years and 7 to 14 years. Patient's age, sex, address, religion and caste, nationality and socio-economic status were recorded. The diagnosis of dermatological condition was based on detail review of history, clinical features physical examination including skin. When necessary diagnosis was confirmed by laboratory investigations such as KOH mount, gram's strain, Wood's lamp examination, diascopy, Tzanck test, hematological and biochemistry analysis, purified protein derivative and skin biopsy as needed. Dermatoses were classified according to the Tenth Revision of International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD-10).[10] The following parameters were studied: sex and age distribution of dermatoses and distribution of dermatoses according to their percentage of frequency. Patients with more than one dermatological condition were excluded from the study.

Result

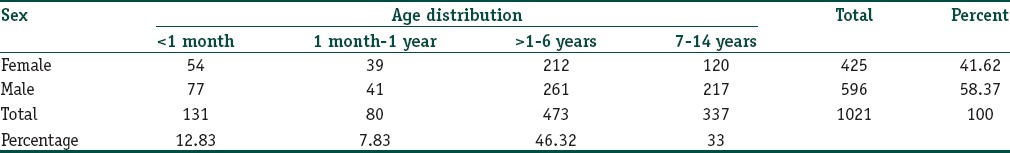

A total of 1021 children were enrolled in the study. Total boys were 596 (58.37%) while girls were 425 (41.62%) with a boy to girl ratio 1.4:1. The neonates constituted 131 (12.83%) of study population. There were 77 (7.54%) boys and 54 (5.28%) girls in neonate's group. 1 month to 1 year age group constituted 80 (7.83%) children with 41 (4.01%) boys and 39 (3.81%) girls. Pre-school group (>1 to 6 years) is the largest group with 473 (46.32%) children constituting 261 (25.56%) boys and 212 (20.76%) girls. There were 217 (21.25%) boys and 120 (11.75%) girls in school going age group of 7 to 14 years [Table 1].

Table 1.

Age and sex wise distribution of children

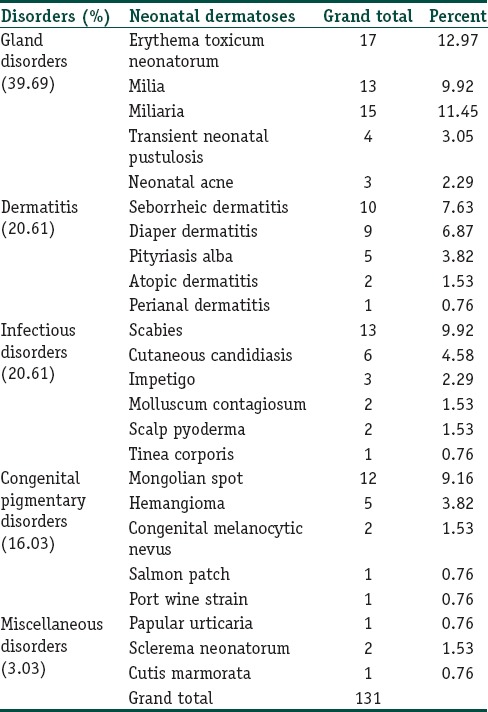

Majority of the skin conditions in neonates were transient (physiological) and constituted 39.69% followed by dermatitis (20.61%), infectious disorders (20.61%) and congenital pigmentary disorders (16.03%) in decreasing order. Most common transient disorders in neonates were erythema toxicum neonatorum (12.97%) [Figure 1], miliaria (11.45%), and milia (9.92%). Scabies (9.92%) and cutaneous candidiasis (4.58%) were common infectious disorders. Mongolian spot (9.16%) was predominant congenital pigmentary disorder. Seborrheic dermatitis (7.63%) and diaper dermatitis (6.87%) were common dermatitis disorders [Table 2].

Figure 1.

A case of erythema toxicum neonatorum in a neonate

Table 2.

Pattern of various dermatoses in neonates

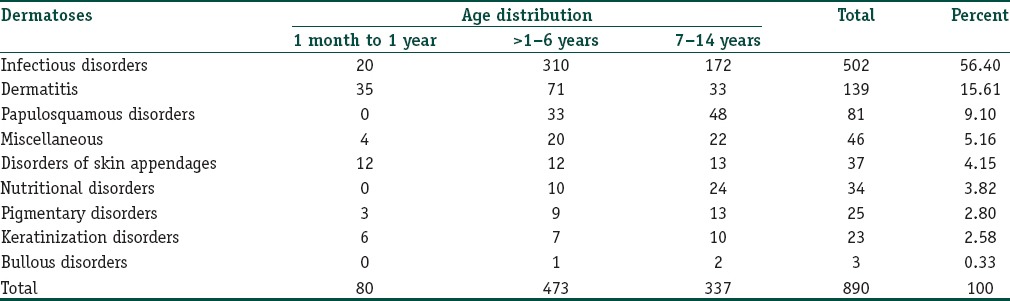

In overall, >1 month to 14 years age group the most common type of dermatoses found in our study was infectious disorder constituting a total of 56.40% of the study population followed by dermatitis (15.61%), papulosquamous disorders (9.10%), disorder of skin appendages (4.15%) and nutritional disorders (3.82%) in order of prevalence [Table 3].

Table 3.

Pattern of various dermatoses in >1 month age group

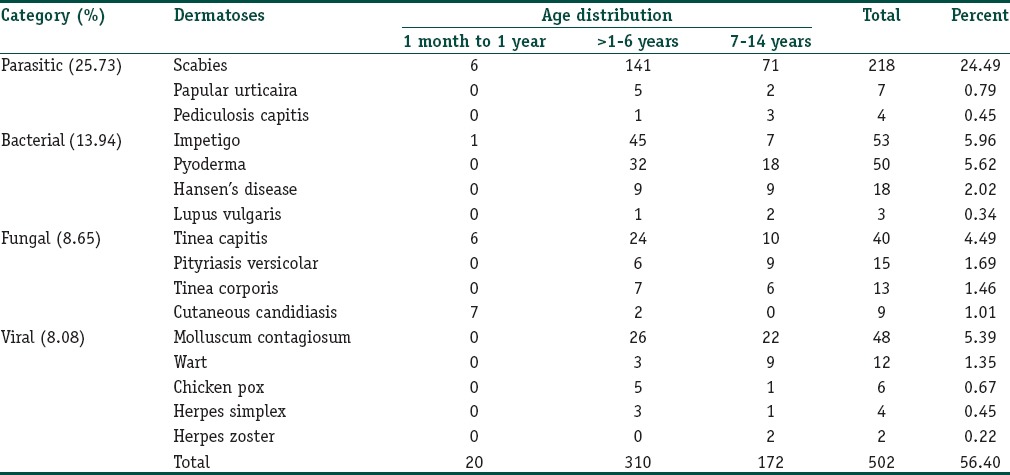

Among infectious disorder in study population of > 1 month to 14 years age group, children were found to be affected most by parasitic infestation (25.73%) mostly constituted by scabies (24.49%). Incidence of impetigo and pyoderma comprised 5.96% and 5.62%, respectively [Table 4].

Table 4.

Distribution of patients (>1 month age group) with infectious disorders according to their individual etiology

Molluscum contagiosum (5.39%) [Figure 2] was the most common of all viral infections followed by viral warts (1.35%). Tinea capitis (4.49%) [Figure 3] comprised most cases of fungal infections in study population. Childhood leprosy was found in 2.02% of study population [Table 4].

Figure 2.

A case of molluscum contagiosum in a 10-year-old girl

Figure 3.

A case of tinea capitis in a 5-year-old female child

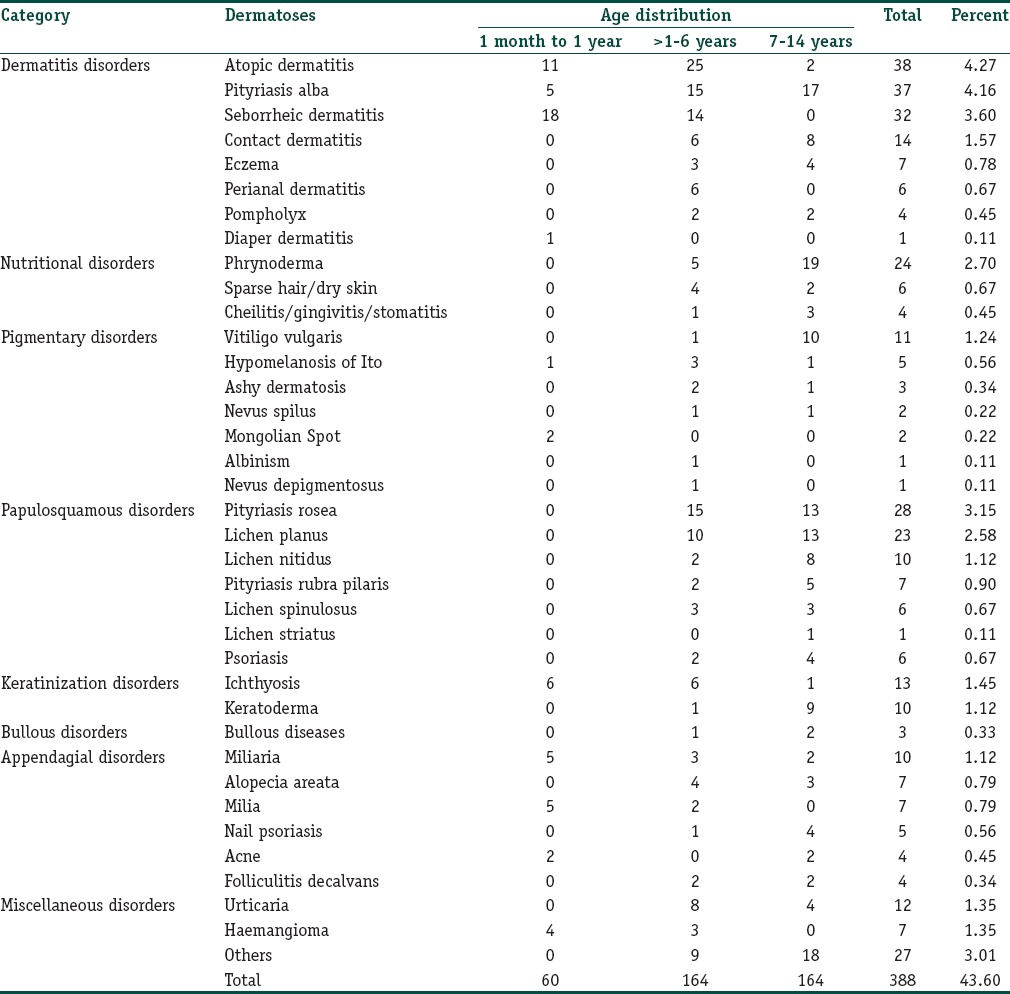

In > 1 month to 14 years age group of children, more common non-infectious disorders were atopic dermatitis (4.27%) [Figure 4], pityriasis alba (4.16%), seborrheic dermatitis (3.60%), pityriasis rosea (3.15%), phrynoderma (2.70%) lichen planus (2.58%), contact dermatitis (1.57%), ichthyosis (1.45%), urticaria (1.35%), hemangioma (1.35%), vitiligo vulgaris (1.24%), lichen nitidus (1.12%), pityriasis rubra pilaris (0.9%), and alopecia areata [Figure 5] [Table 5].

Figure 4.

A case of atopic dermatitis in 2-month-old child

Figure 5.

A case of alopecia areata of scalp

Table 5.

Distribution of patients (>1 month age group) with non-infectious disorders according to their individual etiology

Miscellaneous group in children included cases of urticaria (12), hemangioma (7) [Figure 6], keloid (6), linear epidermal nevus (4), HIV (4), morphea (3), granuloma annulare (2), lymphangiactasia (2), exanthematous eruption (2), lymphangiohaemangioma (1), neurofibromatosis type 1 (1), and xeroderma pigmentosa (1) [Table 5].

Figure 6.

A case of hemangioma on left thigh a 6-month-old child

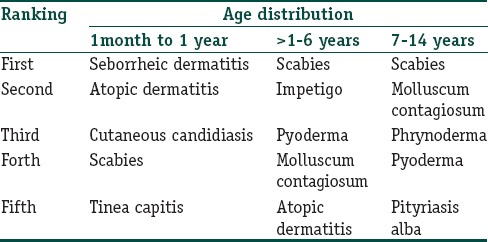

We observed that seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, cutaneous candidiasis, scabies and tinea capitis were more common in 1 month to 1 year age group in order of prevalence. In pre-school age group (>1 to 6 years) scabies, impetigo, pyoderma, molluscum contagiosum and atopic dermatitis were common. While in school-going children (7 to 14 years) most common diseases were scabies, molluscum contagiosum, phrynoderma, pyoderma and pityriasis alba in order of incidence [Table 6].

Table 6.

Commonest skin disorders among children according to age group

Discussion

Skin diseases are a major health problem in the pediatric age group and are associated with significant morbidity. Skin diseases in the pediatric age group can be transitory or chronic and recurrent. Cutaneous infections are common in children during school going years. Most of the cutaneous diseases that result from intrinsic genetic abnormalities also have onset in the pediatric age-group.

Most of the skin diseases were seen in pre-school age group (46.32%) followed by school-going children (33%) and neonates (12.83%) except birth marks and common genetic disorders. This is almost in accordance with the previous study done in large pediatric hospital in Delhi.[11]

The majority of skin conditions in neonates are transient (physiological) and constituted 39.69% that is less than in other studies like Nobbay and Chakrobarthy (69%),[12] Baruah et al.(93%),[13] Kulkarni and Singh (72%),[14] Federman[15] and Patel (78%).[16] Reason for this may be infectious disease is more common in our study comparative to other studies.

Erythema toxicum neonatorum is the most common transient disorder in newborn, a benign condition requiring no intervention, presented in 12.97% of neonates in this study; reported incidence is 21–40%.[17,18,19,20]

Second most common condition noted was miliaria (11.45%). Incidence varies from 2.6% to 9.6% in other studies.[12,13,16,17,20,21] Incidence of milia was 9.92% which is comparable with incidence in other Indian studies.[14,16,17,18,21,22]

Mongolian spot was seen only in 9.16% of neonate, frequency is less common than reported in other studies.[12,13,14,17,18] These were seen more commonly in male neonates and more among term babies. A higher incidence was observed in multipara and in babies with more birth weight.

Among infectious disorders, scabies (9.92%) was common in neonates in our study that differ from other study.[16] Reason being that family of neonates belongs to lower socio-economic strata.

Seborrheic dermatitis was found in 7.63% of neonates, finding comparable with that in Patel et al.[16] and Dash et al.[17] studies.

In > 1 month to 14 years age group, the most common dermatoses found in our study were infectious disorders that were 56.40% of the study population. In their study, Dogra and Kumar[23] found only 11.4% of disorders of infectious etiology; however, various other authors in India have reported that disorders of infectious and infestations etiology contributed to 35.6% to 85.2%.[24,25,26,27]

The most frequent and prevalent infectious skin disease in this study was parasitic infestation similar to result obtained by Bhatia,[25] Negi[26] and Sharma.[28]

Scabies (24.49%) was the most prevalent infestation and it was the most common cause of skin disorders in the present study. Incidence rate of scabies, found in other reports, ranges from 5.1% to 22.4%.[23,24,25,26,27,28,29] In this study, the incidence of infestation by pediculosis capitis was 0.45% which is similar to a study by Rao et al. (0.5%).[29] Other studies in India found more incidence of pediculosis capitis about 54%.[25,26,28,29]

Diverse overseas studies have different infestation rates such as 19% in Israel, 33.7% in Australia, 50% in Brazil and 81.5% in Argentina.[6,30,31,32] High rate of scabies in our study could be due to poor hygiene, most cases from low socio-economic strata and overcrowding.

Bacterial infections were the second in frequency among infectious disorders comprising 13.94% compared to other study like Patel et al. (24.90%)[16] and Thappa (25.64%).[33]

Among bacterial infections, impetigo (5.96%) and pyoderma (5.62%) were most prevalent. This incidence was less than that found in other studies.[24,25,26,28]

In this study, molluscum contagiosum (5.39%) was most common of all viral infections, followed by viral warts (1.35%); similar to findings observed by the study of Sharma and Mendiratta.[34] While studies of Patel (1.53%),[16] and in countries like Turkey, Switzerland, recently in Taiwan and Nigeria where the higher incidence of warts in children were found.[1,3,35,36]

The incidence of fungal infection was 8.65% in our study, which was mainly observed in the older age group. These findings supported by other studies like Patel et al. (7.81%)[16] Thappa (8.49%),[33] Sharma[34] and Ben Saif and Al Shehab.[37] Tinea capitis (4.49%) was the most common fungal infection mainly among older age group similar with finding of other studies.[2,3]

Low incidence of fungal infections may be related to newspaper and television advertisements of antifungal products, maturation of sweat glands, and easy availability of over-the-counter products in the urban area.

Prevalence of leprosy patients in age group of > 1 month–14 years was 2.02% that relate with findings in recent studies done in Delhi (9.61%)[38] and Hyderabad (9.81%).[39] Despite the statistical elimination of leprosy in this region, childhood leprosy cases continue to present in alarming numbers. The children were largely immigrants from the endemic neighboring states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

In the present study, the incidence of dermatitis (15.61%) was second most common among all dermatoses which is higher than the incidence in Dogra and Kumar (5.2%)[23] and Johnson and colleagues (4.66%).[40]

The incidence of atopic dermatitis (4.27%) was similar with other studies performed in developed countries, where they found rates ranging from 3% to 28%.[15,30,41,42] We found seborrheic dermatitis in 3.60% of study population mainly in > 1 month to 1 year age group, similar incidence was found in other studies of Patel et al. (1.82%)[16] and Ben Saif and Al Shehab (3.4%)[37]

Pityriasis alba was found to be 4.16% in our study, Same incidence was found in other studies.[2,26] Pityriasis alba was observed more in the 1 to 14 years old age group. The higher incidence may be because of the growth period in children, irregular and inadequate food habits, worm infestation and in some cases socio-economic factors.

Incidence of eczema in our study reported was 0.78%, while other western studies, however ranged their incidence of eczema from 18% to 34%.[40,41,42,43,44] Low frequency of atopic dermatitis and eczema may be related to climate, dietary habits, genetics, or other unknown factors.

Papulosquamous disorders affected 9.10% of study population comparably higher than incidence recorded in study from Egypt.[45] Surprisingly in our study pityriasis rosea was most common papulosquamous disorder affecting about 3.15% of study population which is comparable to observation of a study in Ben Saif and Al Shehab (2.1%).[37] Pityriasis rosea accounts for approximately 2% of outpatient visits in dermatology.[46]

In our study, lichen planus was observed in 2.58% of study population which is similar to the finding in Samman (2%)[47] and Handa and Sahoo (2%),[48] while Kumar and colleagues[49] and Luis-Montoya and colleagues[50] found higher incidences of about 11.2% and 10.2%, respectively.

Incidence of pityriasis rubra pilaris is found in 0.90% of study population. Its incidence might vary; it is 1 in 5000 in Great Britain[51] and 1 in 50,000 in India[52] in an outpatient setting.

Psoriasis had frequency of 0.67% in this study. Nearly similar observations were reported in Rao and assoc.[29] and Sardana K[11] studies.

Incidence of pigmentary disorders in our study was found to be 2.80% similar to study of Thappa (3.16%),[33] while higher incidence were found in Patel et al. (11.48%)[16] and Ben Saif and Al Shehab (8.9%)[37] studies.

Nutritional disorders were found in about 3.82% of children, which was less than the 17.5% found in a study by Negi and associates.[26] This difference may exist because the study by Negi and associates[26] was done in a rural area while our study center was in an urban area. Incidence of phrynoderma was more common in our study.

Keratinization disorders such as ichthyosis (1.45%) and palmoplanter keratoderma (1.12%) were similar to finding in study by Ghosh et al.[27] and Porter et al.[53] Incidence of hair and nail disorders were 1.8%, finding less than the study of Thappa (5.2%)[33] and Ben Saif and Al Shehab (11%).[37] Urticaria affects about 1.35% of study population which correlates with other study.[33]

Conclusion

The study shows that infections and infestation disorders were more common in the pediatric age group that can be controlled easily by public awareness, proper sanitation and providing health care facilities by training the dermatologists, pediatricians and general practitioners about the management of common skin disorders. But many non-infectious disorders that need dermatologist's opinion should be referred to them. Due to wide variety, burden and public health problem of skin diseases in children, more dermatologists should be trained in pediatric dermatology subspecialty. Data can be useful in planning of health care programs for children.

What is new?

This is the only epidemiological study of paediatric dermatoses in south Gujarat region. Not surprisingly infectious disorders constituted 56.40% of the total study population in our study. Despite the high frequency of certain skin diseases in developing countries like India they have so far not been regarded as a significant health problem in the development of public health strategy.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Chen GY, Cheng YW, Wang CY, Hsu TJ, Hsu MM, Yang PT, et al. Prevalence of skin diseases among schoolchildren in Magong, Penghu, Taiwan: A community-based clinical survey. J Formos Med Assos. 2008;107:21–9. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(08)60004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Survey of clinical paediatrics. 6th ed. London: Mcgraw Hill Kogakusha Ltd; 1974. Wasserman Edward And Slobody Lawrence. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wisuthsarewong W, Viravan S. Analysis of skin diseases in a referral pediatric dermatology clinic in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2000;83:999–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serarslan G, Savas N. Prevalence of skin diseases among children and adolescents living in an orphanage in Antakya, Turkey. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:490–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laude TA. Approach to dermatologic disorders in black children. Semin Dermato. 1995;14:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(05)80034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roger M, Barnetson RS. Diseases of skin. In: Campbell AGM, Mcintosh N, editors. Fortar and Arneil's Textbook of pediatrics. 5th ed. New York, NY: Churchil Levingstone; 1998. pp. 1633–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bechelli LM, Haddad N, Pimenta WP, Pagnano PM, Melchior E, Jr, Fregnan RC, et al. Epidemiological survey of skin diseases in schoolchildren living in the Purus Valley (Acr State, amzonia, brazil) Dermatologica. 1981;163:78–93. doi: 10.1159/000250144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams H, Stewart A, Von Mutius E, Cookson W, Anderson HR. Is eczema really on the increase worldwide? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:947–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma NK, Garg BK, Goel M. Pattern of skin diseases in urban school children. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1986;52:330–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.2nd edn. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. WHO. ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sardana K, Mahajan S, Sarkar R, Mendiratta V, Bhushan P, Koranne RV, et al. Spetrum of Skin Disease among Indian Children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:6–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nobbay B, Chakrabarty N. Cutaneous manifestation in the new-born. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1992;58:69–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baruah MC, Bhat V, Bhargava R, et al. Prevalence of dermatoses in the neonates in Pondicherry. Indian J Dermatoi Venereol Leprol. 1991;57:25–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulkarni ML, Singh R. Normal variants of skin in neonates. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996;62:83–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Federman DG, Reid M, Feldman SR, Greenhoe J, Kirsner SR. The primary care provider and the care of skin disease: The patient's perspective. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:25–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.137.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel JK, Vyas AP, Berman B, Vierra M. Incidence of childhood dermatoses in India. Skinmed. 2010;8:136–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dash K, Grover S, Radhakrishnan S, Vani M. Clinico epidemiologicol study of cutaneous manifestations in the neonate. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2000;66:26–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nanda A, Kaur S, Bhakoo ON, Dhall K. Survey of cutaneous lesions in Indian newborns. Pediatrics Dermatol. 1989;6:39–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1989.tb00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saraeli T, Kenney JA, Scott RB. Common skin disorders in the newborn Negro infant. J Pediatr. 1963;63:358–62. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(63)80132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hidano A, Purwoko R, Jitsukawa K. Statistical survey of skin changes in Japanese neonates. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:140–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1986.tb00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sachdeva M, Kaur S, Nagpal M, Dewan SP. Cutaneous lesions in new born. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002;68:334–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Javed M. Clinical spectrum of neonatal skin disorders at Hamdard University Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan. [Last accessed on 2014 Dec 16];Our Dermatol Online. 2012 3:178–80. Available from http://www.odermatol.com/wp-content/uploads/file/2012%203/DOI-4%281%29.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dogra S, Kumar B. Epidemiology of skin diseases in school children: A study from northern India. Pediatr Dermato. 2003;20:470–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2003.20602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balai M, Khare AK, Gupta LK, Mittal A, Kuldeep CM. Pattern of pediatric dermatoses in a tertiary care centre of South West Rajasthan. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:275–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.97665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhatia V. Extent and pattern of paediatric dermatoses in rural areas in central India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1997;63:22–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Negi KS, Kandpal SD, Prasad D. Pattern of skin diseases in children in Garhwal region of uttar pradesh. Indian Pediatr. 2001;38:77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh SK, Saha DK, Roy AK. A clinico-aetiological study of dermatosis in pediatric age group. Indian J Dermatol. 1995;40:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma NL, Sharma RC. Prevalence of dermatologic diseases in school children of a high altitude tribunal area of Himachal Pradesh. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1990;56:375–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao GS, Kumar SS, Sandhya Pattern of skin diseases in an Indian village. Indian J Med Sci. 2003;57:108–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Speare R, Buettner PG. Head lice in pupils of a primary school in Australia and implications for control. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:285–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chouela E, Abeldano A, Cirigliano M, Ducard M, Neglia V, La Forgia M, et al. Head louse infestations: Epidemiologic survey and treatment evaluation in Argentina schoolchildern. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:819–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mumcuoglu KY, Klaus S, Kafka D, Teiler M, Miller J. Clinical observations related to head lice infestation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:248–51. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70190-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thappa DM. Common skin problems. Indian J Pediatr. 2002;69:701–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02722708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma RC, mendiratta V. Clinical profile of cutaneous infections and infestations in paediatric age group. Indian J Dermatol. 1999;44:174–8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wenk C, Itin PH. Epidemiology of pediatric dermatology and allergology in the region of Aargau, Switzerland. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:482–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2003.20605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yahya H. Change in pattern of skin disease in Kaduna, north-central Nigeria. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:936–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ben Saif GA, Al Shehab SA. Pattern of Childhood Dermatoses at a Teaching Hospital of Saudi Arabia. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2008;2:63–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singal A, Sonthalia S, Pandhi D. Childhood leprosy in a tertiary-care hospital in Delhi, India: A reappraisal in the post-elimination era. Lepr Rev. 2011;82:259–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jain S, Reddy RG, Osmani SN, Lockwood DN, Suneetha S. Childhood leprosy in an urban clinic Hyderabad, India: Clinical presentation and the role of household contacts. Lepr Rev. 2000;73:248–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prevalence, morbidity, and cost of dermatological diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;73:395–401. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12541101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bowker NC, Cross KW, Fairburn EA, Wall M. Sociological implications of an epidemiological study of eczema in the city of Birmingham. Br J Dermatol. 1976:95:137–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horn R. The pattern of skin diseases in general practice. Dermatol Pract. 1986;2:14–9. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katelaris CH, Peake JE. Allergy and the skin: Eczema and chronic urticaria. Med J Aust. 2006;185:517–22. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiang LC, Chen YH, Hsueh KC, Huang JL. Prevalence and severity of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema in 10- to 15 year old schoolchildren in central taiwan. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2007;25:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mostafa FF, Hassan AA, Soliman MI, Nassar A, Deabes RH. Prevalence of skin diseases among infant and children in Al Sharqia Governorate, Egypt. [Last accessed on 2014 Dec 18];Egyptian Dermatol Online J. 2011 8:1–4. Available from http://www.edoj.org.eg/vol008/0801/004/01.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gonzalez LM, Allen R, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA. Pityriasis rosea: An important papulosquamous disorder. Int J Dermatol. 2005:44:757–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samman PD. Lichen planus: An analysis of 200 cases. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1961;46:36–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Handa S, Sahoo B. Childhood lichen planus: A study of 87 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:423–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar V, Garg BR, Baruah MC, Vasireddi SS. Childhood lichen planus (LP) J Dermatol. 1993;20:175–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1993.tb03854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luis-Montoya P, Dominguez-Soto L, Vega-Memije E. Lichen planus in 24 children with review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:295–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.22402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Griffiths WA. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:105–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1980.tb01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sehgal VN, Jain MK, Mathur RP. Pityriasis rubra pilaris in Indians. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:821–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb08229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Porter MJ, Mack RW, Chaudhary MA. Pediatric skin disease in pakistan. A study of three Punjab villages. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:613–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1984.tb05701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]