Photoemission established tantalum phosphide as a Weyl semimetal, which hosts exotic Weyl fermion quasiparticles and Fermi arcs.

Keywords: Weyl Fermion, Fermi arc, Topological physics, Weyl semimetal, Topological insulator

Abstract

Weyl semimetals are expected to open up new horizons in physics and materials science because they provide the first realization of Weyl fermions and exhibit protected Fermi arc surface states. However, they had been found to be extremely rare in nature. Recently, a family of compounds, consisting of tantalum arsenide, tantalum phosphide (TaP), niobium arsenide, and niobium phosphide, was predicted as a Weyl semimetal candidates. We experimentally realize a Weyl semimetal state in TaP. Using photoemission spectroscopy, we directly observe the Weyl fermion cones and nodes in the bulk, and the Fermi arcs on the surface. Moreover, we find that the surface states show an unexpectedly rich structure, including both topological Fermi arcs and several topologically trivial closed contours in the vicinity of the Weyl points, which provides a promising platform to study the interplay between topological and trivial surface states on a Weyl semimetal’s surface. We directly demonstrate the bulk-boundary correspondence and establish the topologically nontrivial nature of the Weyl semimetal state in TaP, by resolving the net number of chiral edge modes on a closed path that encloses the Weyl node. This also provides, for the first time, an experimentally practical approach to demonstrating a bulk Weyl fermion from a surface state dispersion measured in photoemission.

INTRODUCTION

Recent developments in low-energy condensed matter physics have established a new route to study fundamental aspects of high-energy physics (1, 2). This can help scientists to design better materials leading to new technologies and devices. The experimental realization of Dirac fermions in crystalline solids such as graphene and topological insulators has become one of the main themes of condensed matter physics in the past 10 years (3–6). A particle that is relevant for both high-energy and condensed matter physics is the Weyl fermion (7). Weyl fermions may be thought of as the building blocks for any fermion. Therefore, one-half of a charged Dirac fermion of a definite chirality is called a Weyl fermion. Although Weyl fermions play a crucial role in quantum field theory, they are not known to exist as fundamental particles in vacuum.

Recent advances in topological condensed matter physics provided new perspectives into realizing this elusive particle (8–11). It was proposed that an exotic type of topologically nontrivial metal, the Weyl semimetal, can host Weyl fermions as its low-energy quasiparticle excitations. The resulting singly degenerate bands contain relativistic and massless states that touch at points, the Weyl nodes, and disperse linearly in all three momentum space directions away from each Weyl node. Weyl fermions have distinct chiralities, either left-handed or right-handed. In a Weyl semimetal crystal, the chiralities of the Weyl nodes give rise to topological charges, which can be understood as monopoles and antimonopoles of Berry flux in momentum space. The separation of the opposite topological charges in momentum space directly leads to the topologically nontrivial phase in Weyl semimetals. Hence, it protects surface state Fermi arcs that form an anomalous band structure consisting of disconnected curves that connect the projections of Weyl nodes with opposite topological charges on the boundary of a bulk sample. In contrast to the Dirac fermion states realized in graphene (3), topological insulators (4–6), and Dirac semimetals (6, 12), the Weyl semimetal state does not require any symmetry for its protection except the translation symmetry of the crystal lattice itself. The unique robustness of the Weyl fermions suggests that they could be exploited to carry electric currents more efficiently than normal electrons, thereby possibly pushing electronics to new heights. The first-ever realization of Weyl fermions in all of physics—the new topological classification, the exotic Fermi arc surface states, the predicted quantum anomalies, and the prospects in device and applications suggest Weyl fermions and Weyl semimetals as the next era (after Dirac) in condensed matter physics (8–17).

Despite the interest on Weyl semimetals, they are extremely rare in nature and, for many years, there was no successful realization of a Weyl semimetal in a real material. Recently, a family of isostructural compounds, tantalum arsenide (TaAs), niobium arsenide (NbAs), tantalum phosphide (TaP), and niobium phosphide (NbP), was proposed as Weyl semimetals; shortly after the theoretical prediction (18, 19), the first Weyl semimetal was experimentally discovered in TaAs (20). Around the same time, Weyl points were also observed in a nonfermionic system, a photonic crystal (21). The electronic Weyl system (TaAs) was experimentally observed via photoemission (20, 22). Other later independent experiments have confirmed the Weyl state in TaAs and have shown the Weyl state in the other member, NbAs (23–25). Both TaAs and NbAs contain arsenic. Here, we report the experimental observation of a Weyl semimetal without toxic elements in TaP.

We use soft x-ray angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (SX-ARPES) (26, 27) and ultraviolet ARPES to study the bulk and surface band structure, respectively, of TaP. In the bulk, we observe point degeneracies at arbitrary points in the Brillouin zone (BZ), with bands that disperse linearly in all directions in momentum space away from the degeneracy, which demonstrates Weyl points and Weyl cones in the bulk of TaP. We observe Fermi arc surface states on the surface of TaP. Our results are qualitatively consistent with first-principles calculations, providing further support to our experimental data and demonstrating unambiguously that TaP is a Weyl semimetal. Moreover, we present an experimentally practical approach to demonstrating the bulk-boundary correspondence of a Weyl semimetal by resolving the net number of chiral edge modes on a closed path that encloses the Weyl node. Our results not only identify the Weyl semimetal state in TaP but also demonstrate a systematic experimental methodology that can be more generally applied to discover other Weyl semimetals and to measure their topological invariants.

RESULTS

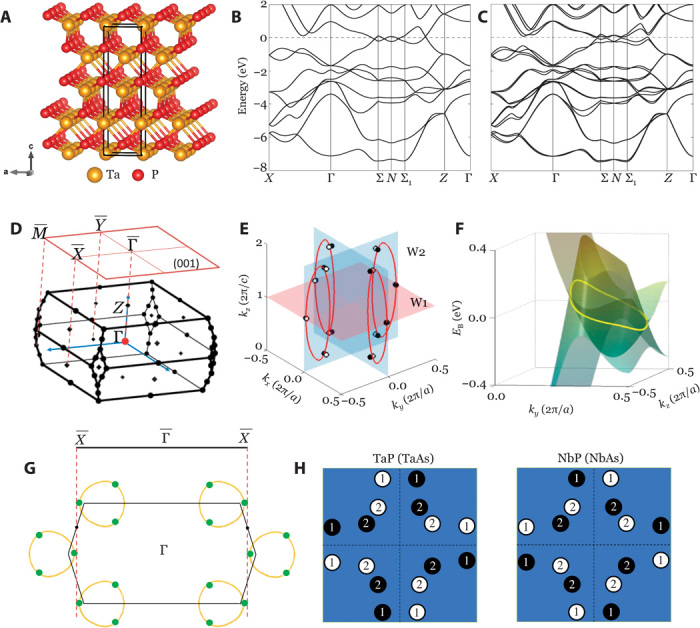

TaP crystallizes in a body-centered tetragonal Bravais lattice, space group I41md (109), point group C4v. X-ray diffraction measurement showed that the lattice constants of our TaP samples are a = 3.32 Å and c = 11.34 Å, consistent with earlier crystallographic studies (28). The basis consists of two Ta atoms and two P atoms, as shown in Fig. 1A. In this crystal structure, each layer is shifted relative to the layer below by half a lattice constant in either the x or the y direction. This shift gives the lattice a screw pattern along the z direction, which leads to a nonsymmorphic C4 rotation symmetry that includes a translation along the z direction by c/4. We note that TaP lacks space inversion symmetry. The breaking of space inversion symmetry is a crucial condition for the realization of a Weyl semimetal, because in the absence of inversion symmetry, all bands are generically singly degenerate. In Fig. 1D, we show the bulk BZ and (001) surface BZ of TaP. In Fig. 1 (B and C), we show the calculated band structure along some high-symmetry lines. It can be seen that the conduction and valence bands cross each other near the Σ, Σ′, and N points, giving rise to a semimetal ground state. In the absence of spin-orbit coupling (SOC), it can be seen that the overlap of the conduction and valence bands yields four ring-like crossings, or nodal lines, in the kx = 0 and ky = 0 mirror planes, as shown in Fig. 1E. When SOC is taken into account, the nodal lines dissolve into point band crossings, the Weyl nodes, which are shifted away from the kx = 0 and ky = 0 mirror planes. We show the positions of the Weyl points from calculation in Fig. 1E. The black and white circles represent Weyl points of opposite chiralities, the blue planes are mirror planes, and the red plane is the kz = 2π/c plane. Our band structure calculation shows that there are 24 Weyl nodes, which can be categorized into two groups, W1 and W2. W1 represents the 8 Weyl nodes that are located on the kz = 2π/c plane, and W2 represents the remaining 16 Weyl nodes that are away from the kz = 2π/c plane. In Fig. 1F, we show the dispersion at the kx = 0 mirror plane, E(kx = 0, ky, kz), around the nodal line (yellow line) when SOC is ignored. We note that the nodal line disperses in energy (Fig. 1F). Because the Weyl nodes emerge at k points near the nodal line upon the inclusion of SOC, the dispersion of the nodal line leads to an energy offset between the W1 and W2 Weyl nodes. All W1 Weyl nodes project as single Weyl nodes in the close vicinity of the surface BZ edge and points. Contrary to W1, pairs of W2 Weyl nodes with the same chiral charge project onto the same point of the (001) surface BZ. Moreover, the eight projected W2 Weyl nodes have a projected chiral charge of ±2. The locations of the Weyl nodes and their projected chiral charge are schematically shown in Fig. 1H for the (001) surface of TaP (TaAs) and NbP (NbAs) in the left and right panels, respectively. An important difference between the left and right panels of Fig. 1H is their difference in the W1 chiralities. The projected chiral charge for the W1 Weyl nodes on the (001) surface is opposite for TaP (TaAs) and NbP (NbAs). This effect is not due to the k-space exchange of the W1 Weyl nodes’ chiral charge in the bulk. Instead, it arises from how the W1 is projected onto the (001) surface. As shown in Fig. 1G, it depends on whether the W1 is to the left or to the right of the N point. That is, there is no topological phase transition in the bulk by going from TaP to NbP. However, on the surface, the projected W1 Weyl nodes will move around; hence, it would be interesting to study how the Fermi arcs associated with the W1 Weyl node evolve in this process if they can be resolved experimentally.

Fig. 1. Electronic band structure of the Weyl semimetal TaP.

(A) Body-centered tetragonal structure of TaP, shown as stacks of Ta and P layers. (B) First-principles band structure calculation of the bulk TaP without SOC. (C) Same as (B) but with SOC. Schematic of the distribution of Weyl nodes in the three-dimensional BZ of TaP. (D) Bulk BZ and (001) surface BZ of TaP, with certain high-symmetry points labeled. (E) Calculation of the positions of the Weyl nodes, with opposite chiralities indicated by the white and black circles. The mirror planes are blue and the kz = 2π/c plane is red. (F) Band structure on the kx = 0 mirror plane, E(kx = 0, ky, kz), in the vicinity of the ring-like crossing, in yellow, which we find in calculation when SOC is ignored. (G) Calculation showing the ring-like crossings in the kx = 0 plane, with the Weyl nodes indicated by green dots. The distribution of chiralities of the projected W1 nodes in the first surface BZ depends on whether the ring-like crossing is large enough that the W1 nodes spill over the edge of the first surface BZ, marked by the dotted line through the bulk N point. (H) To more clearly understand the distribution of chiralities, we show cartoons (not to scale) of the projected Weyl nodes and their chiral charges on the (001) Fermi surface of TaP (TaAs) and NbP (NbAs), respectively. The projected Weyl nodes are denoted by black and white circles; their color indicates their opposite chiralities and the number in the circle indicates the projected chiral charge. We find that the chiralities of the W1 points are swapped in TaP (TaAs) with respect to NbP (NbAs).

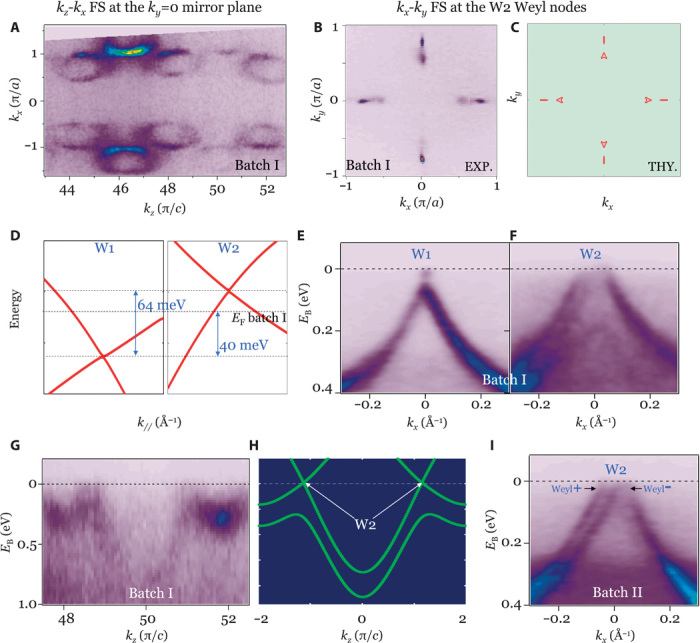

We now present ARPES data to study the electronic structure of TaP. Specifically, we use SX-ARPES (hν = 350 to 1000 eV), which is reasonably bulk-sensitive (26, 27) and therefore selective in kz (29), to measure the bulk band structure, and we use vacuum ultraviolet ARPES (hν = 35 to 90 eV), which is surface-sensitive, to measure the surface band structure. We begin our discussion by presenting the measurements of the bulk Weyl cones using SX-ARPES. In Fig. 2A, we show the SX-ARPES–measured kz − kx Fermi surface map over multiple BZs along the kz direction for a TaP crystal from Batch I. The observed kz dispersion in Fig. 2A demonstrates that SX-ARPES is predominantly bulk-sensitive. Figure 2B shows the SX-ARPES–measured kx − ky Fermi surface at the kz value corresponding to the W2 Weyl nodes by using an incident photon energy of 650 eV. In Fig. 2C, we show a kx − ky calculation of the Fermi surface performed at the kz value of the W2 Weyl nodes. The chemical potential of the sample is estimated to be about 20 meV below the W2 Weyl node (further discussed below). The calculated Fermi surface is in qualitative agreement with the ARPES data. It can be seen that the Fermi pockets that arise from the two nearby W2 Weyl nodes are merged into one because the chemical potential is below the W2 Weyl nodes. Figure 2 (E and F) shows the energy dispersion near the W1 and W2 Weyl nodes along an in-plane momentum space cut direction that goes across a pair of W1 (W2) Weyl cones. The spectrum shows a linear dispersion in the in-plane directions. Because the cuts to cross a pair of nearby cones are chosen, one would expect to see two Weyl nodes along each cut. However, for W1 (Fig. 2E), we cannot resolve the two nodes because they are too close to each other in k-space. For W2 (Fig. 2F), we also cannot resolve the two nodes possibly because the chemical potential is below the Weyl nodes. For the W1 Weyl cone observed in Fig. 2F, our data shows the upper Weyl cone. The W1 Weyl node is found to be about 40 meV below the Fermi level according to our data. Note that, in our calculation, we find that there is a 64-meV offset in energy for the W1 and W2 Weyl nodes, as shown in Fig. 2D. From these two facts, we know that the chemical potential is about 24 meV below the W2 Weyl nodes. Furthermore, because a Weyl cone disperses linearly in all three directions, it is crucial to study the dispersion of the W2 Weyl bands along the out-of-plane kz direction. By fixing kx and ky at the location corresponding to the W2 Weyl node, we are able to study the energy dispersion as a function of kz. As shown in Fig. 2G, the Weyl cone is observed to have a strong kz dispersing character, which demonstrates its three-dimensional nature. Around kz = ±1.3π/c, the observed dispersion in the data is consistent with the linear dispersion along the kz direction, as shown in Fig. 2H. In Fig. 2I, we report SX-ARPES measurements using a TaP sample from a different batch, Batch II, which is relatively more n-type than Batch I. Following the measurement procedure previously mentioned, the E − kx dispersion is also shown to be linear. Figure 2I shows that the two W2 Weyl nodes form two linearly dispersing bands. We have shown that the bulk bands of TaP form discrete points at the Fermi level in the bulk BZ, that the bands disperse linearly along both in-plane and out-of-plane directions away from the band touching points, and that the band touchings are not located at any high-symmetry points or along any rotational axis. Our ARPES data are consistent with the bulk band calculations. All these together establish the Weyl cones and Weyl nodes in TaP.

Fig. 2. Bulk Weyl fermion cones in TaP.

(A) SX-ARPES Fermi surface (FS) map at ky = 0 in the kz − kx plane. (B) SX-ARPES Fermi surface map at kz = W2 in the kx − ky plane, showing the W2 Weyl nodes. EXP, experimental. (C) Theoretical calculation of the same slice of the BZ at the same energy shows complete agreement with the SX-ARPES measurement. THY, theoretical. (D) First-principles calculations of the energy-momentum dispersion of the two sets of Weyl nodes, W1 and W2, in TaP. The two nodes are offset in energy by 64 meV. (E and F) Energy dispersion maps, E − k//, for W1 and W2, respectively. (G and H) ARPES measured and theoretically calculated out-of-plane dispersion, E − kz, for W2, which shows the linear dispersion of the Weyl cone along the out-of-plane direction. All data in (A) to (G) are obtained from Batch I. (I) Energy dispersion of the W2 Weyl cones from a sample in Batch II. We see the ± Weyl nodes more clearly for Batch II TaP, as labeled in (I).

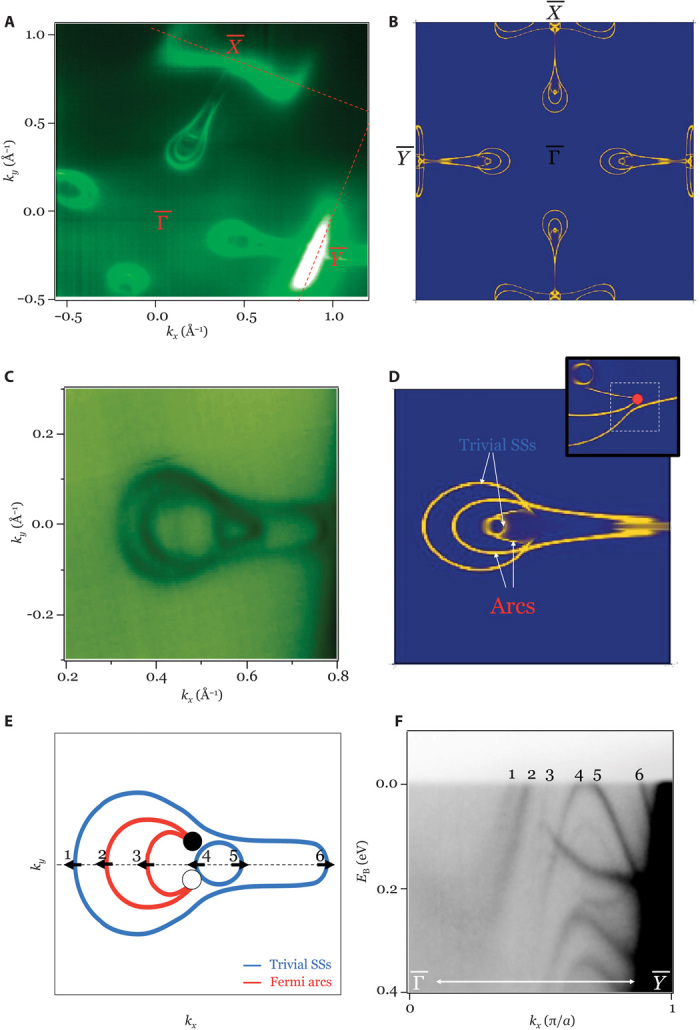

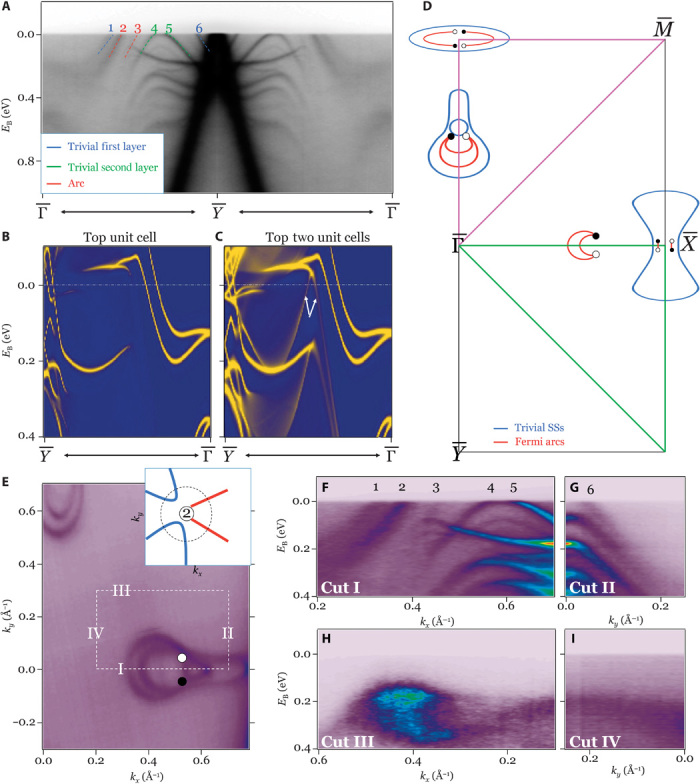

Next, we examine the surface states by using low-energy ARPES. In Fig. 3A, we show a high-resolution ARPES Fermi surface map of the (001) surface of TaP at a photon energy of hν = 50 eV. At the Fermi level, our data shows a bowtie-shaped feature centered at , a long elliptical-shaped feature centered at , and a tadpole-like feature that extends along each or line. Figure 3B shows the theoretically calculated surface Fermi surface of the P termination. The authors claimed in a concurrent photoemission study that they observed surface states from the Ta termination Xu et al. (30). We observe a qualitative agreement between the data and the calculation. Because the pairs of W1 Weyl nodes are very close to each other in k-space, and because the bowtie and long elliptical features show broader spectra than the tadpole features, resolving the Fermi arcs associated with the W1 Weyl nodes is beyond our experimental resolution. We note that this was also the case in both TaAs and NbAs (20, 22, 24, 25). We focus on the surface states near the W2 Weyl nodes because the k separation of the W2 is much larger and well within our experimental resolution. Figure 3C shows a zoomed-in high-resolution Fermi surface of the tadpole along the line. From Fig. 3C, we observe that the tadpole is composed of the following distinct features, going from : two bright and one dark moon-shaped features, one closed inner contour, and a long tail-like feature. Figure 3D shows the corresponding zoomed-in Fermi surface in calculation, where a qualitative agreement can be seen. Specifically, in the calculation, going from , we also observe two bright moon-shaped features, a dark moon-shaped feature, one closed inner contour, and a long tail-like feature. The difference is the location of the closed inner contour. We also note that in the calculation, there are projected bulk bands at the Fermi level in the k-space region of the inner contour, which makes the inner Fermi arc’s spectral weight very weak when it approaches the line in the calculation. We identify the arcs in calculation by further zooming near the neck region of the tadpole, shown in the inset of Fig. 3D. It can be seen that the second bright moon and the dark moon features are the arcs because they terminate onto the Weyl nodes. Other features are trivial surface states because they avoid the Weyl nodes, although the avoid crossing is quite small. Resolving the arcs in experiments by the same method is beyond our resolution because the Weyl nodes have very low spectral weight at low photon energies and because the surface states are very close to each other. In Fig. 4, we will experimentally demonstrate that among all of the surface states that we observe near the W2 Weyl nodes, there are exactly two that must be Fermi arcs. Here, in Fig. 3E, we show a schematic configuration of the surface states that correspond to our data in Fig. 3C. The assignment of Fermi arcs and trivial surface states is made by comparison between our ARPES data (Fig. 3C) and calculation (Fig. 3D). We study the energy dispersion of the tadpole feature on the line. As shown in Fig. 3F, there are six surface states associated with the tadpole feature crossing the Fermi level. We identify an important origin for the observed trivial surface states. Figure 4 (B and C) shows the calculated surface state dispersion along the line. The calculation used the Green function technique to obtain the spectral weight from the top region of a semi-infinite TaP system. Figure 4B shows the surface spectral weight only from the top unit cell, whereas Fig. 4C considers the top two unit cells. It can be seen that the inclusion of the second layer leads to the additional two surface states that cross the Fermi level, as pointed out by the white arrows in Fig. 4C. Therefore, we believe that one of the important origins for the trivial surface states can be the contribution from deeper layers.

Fig. 3. Fermi arc surface states in TaP.

(A and B) ARPES-measured Fermi surface and first-principles band structure calculation of the (001) Fermi surface of TaP, respectively. (C) High-resolution ARPES Fermi surface map in the vicinity of the high-symmetry line. (D) Theoretical calculated surface Fermi surface along . The calculation used the Green function technique to obtain the spectral weight from the top two unit cells of a semi-infinite TaP system. SSs, surface states. (E) Schematic showing the Fermi arcs and the trivial surface states that correspond to our data in (C). This configuration is obtained by analyzing our ARPES data and comparing it with calculations (see the main text). (F) ARPES dispersion along the high-symmetry line. The six Fermi crossings are numbered 1 to 6. We see four states (1 to 4) with one sign of Fermi velocity and the other two (5 and 6) with the opposite sign. This is consistent with the projected chiral charge ±2 for the W2. These six states are also labeled in (E), where the arrows represent their corresponding Fermi velocity direction.

Fig. 4. Bulk-boundary correspondence and topological nontrivial nature of TaP.

(A) ARPES energy-momentum dispersion map along the high-symmetry line, which shows six band crossings at the Fermi level. (B) Calculated energy dispersion along the line. The calculation uses the Green function technique to obtain the spectral weight from the top unit cell of a semi-infinite TaP system. (C) Similar to (B) but for the top two unit cells. (D) Schematic examples of closed paths (green and magenta triangles) that enclose both W1 and W2 Weyl nodes. The bigger black and white circles represent the projected W2 nodes, whereas the smaller ones correspond to the W1 nodes. The red lines denote the Fermi arcs and the blue lines show the trivial surface states. The specific configuration of the surface states in this cartoon is not intended to reflect the Fermi arc connectivity in TaP. It simply provides an example of one configuration of the surface states that is allowed by the projected Weyl nodes and their chiral charges by the bulk-boundary correspondence. (E) Zoomed-in ARPES spectra near the W2 nodes along . The white dashed line marks a rectangular loop that encloses a projected W2 Weyl node. The circles are added by hand on the basis of the calculated locations of the projected W2 nodes. (F to I) ARPES dispersion data as one travels around the k-space rectangular loop shown in (E) in a counterclockwise way from I to IV. The closed path has edge modes with a net chirality of 2, showing that the path must enclose a projected chiral charge of 2 using no first-principles calculations, assumptions about the crystal lattice or band structure, or ARPES spectra of the bulk bands.

DISCUSSION

We discuss the methods that have been used to demonstrate the existence of Fermi arcs. First, according to the literal definition of a Fermi arc, one needs to observe a disjoint segment (a nonclosed curve) that terminates at two Weyl nodes. This can be used in calculations where resolution is sufficient, and indeed, this is the case for our calculation presented in the inset of Fig. 3D. However, in experiments, this is extremely difficult for the TaAs class of compounds because the bulk bands have very low spectral weight at low photon energies and because there are many surface states (both topological and trivial) in the vicinity of each Weyl node. Second, it was proposed by Lv et al. and Yang et al. (22, 25) that one can demonstrate the existence of Fermi arcs in the TaAs class of compounds by observing an odd number of surface state Fermi crossings along the k-space path . It was argued (22) that this is desirable because one can simply count the number of crossings along these high-symmetry lines without worrying about the details of the surface states in the close vicinity of the Weyl nodes. These proposed loops are shown by the green and magenta triangles in Fig. 4D. Here, we show that although this method is theoretically correct, it can be experimentally impractical. The red and blue lines in Fig. 4D show a surface state configuration that is allowed by the projected Weyl nodes and their chiral charges through the bulk-boundary correspondence. Indeed, theoretically, going around the green or magenta triangle should give an odd number of crossings. However, one should note that the pairs of W1 Weyl nodes are very close to each other in k-space. Hence, in Fig. 4D, the Fermi arcs (the red lines) near the point are very short. Similarly, around the point in Fig. 4D, the openings between the two Fermi arcs are very narrow. Therefore, obtaining an odd number of Fermi crossings along the green triangle means that one must experimentally resolve the band crossing that arises from the very short arc near the point. Similarly, obtaining an odd number of Fermi crossings along the magenta triangle means that one must experimentally resolve the opening between the two Fermi arcs (two red lines) near the point. That is, observing an odd number of Fermi crossings along these paths is equivalent to directly resolving the Fermi arcs associated with the W1 Weyl nodes near the or point. Because the W1 Weyl nodes are very close to each other in k-space and because the surface states near the and points have a broad spectrum, resolving their arc character seems to be quite challenging in experiments.

Here, we propose a method to demonstrate the existence of Fermi arcs that is not only theoretically rigorous but also experimentally feasible. We propose to count the net number of chiral edge modes on a closed path that encloses the Weyl node. Specific to the case of TaP (also TaAs and NbAs), we propose the rectangular loop that encloses only one projected W2 Weyl node, as shown in Fig. 4E. In the bulk BZ, the rectangular loop corresponds to a rectangular pipe that encloses two W2 Weyl nodes of chiral charge +1. Therefore, according to the topological band theory, the Chern number on this manifold has to be 2, which implies that there must be two net chiral modes along this rectangular loop. Figure 4 (F to I) shows the ARPES spectrum following the rectangular path in a counterclockwise fashion, from I to IV. We see that, in total, there are four left-moving surface modes and two right-moving surface modes. Therefore, our ARPES data in Fig. 4 (F to I) shows that there are two net chiral edge modes. This means that among the six observed Fermi crossings, two have to be Fermi arcs and the remaining four form closed contours. Theoretically, Fermi arcs are expected to terminate onto Weyl nodes and trivial surface states should avoid them. However, the avoided crossing of trivial surface states with Weyl nodes can be very small in real samples, which is indeed the case for TaP. As seen in Fig. 4E, these surface states are very close to each other at the location of the W2 Weyl nodes (the black and white circles are placed based on the theoretically calculated locations of the W2 Weyl nodes). Thus, experimentally resolving which two out of the six Fermi crossings are the Fermi arcs is not experimentally practical, but at least we unambiguously demonstrate the presence of two Fermi arcs connecting to a projected W2 Weyl node. We note that demonstrating the existence of one set of Fermi arcs is sufficient to establish the Weyl semimetal state. The method described above can also be applied to show Fermi arcs in theoretical calculations. For example, the white dotted rectangular loop in the inset of Fig. 3D encloses one projected W2 Weyl node with the projected chiral charge of 2. Along this loop, there are four Fermi crossings. Three disperse to one direction, whereas the other one disperses to the opposite direction, which also leads to the same result: two net chiral edge modes. Therefore, both the experimental data and the theoretical calculations give consistent results, which are further consistent with the topological band theory. If one chooses the loop used in the experimental data, the counting is more complicated because the inner arc becomes very weak at k points along the loop due to overlap with the bulk projection. We further note that the number of surface state crossings around a projected W2 Weyl node should always equal 2 plus an even number (the inset of Fig. 4E). Here, the first term is required by the projected chiral charge of 2 and the second term represents the fact that additional trivial contours will always contribute an even number of additional crossings. Therefore, around a projected W2 Weyl node, there should always be an even number of surface states, and an odd number of surface states would violate topological band theory. We note that the proposed rectangular loop is experimentally feasible because it only encloses the W2 and not the W1 Weyl node. Therefore, we do not need to resolve the surface states near the W1 nodes, which is experimentally difficult because of their proximity. Finally, we discuss the difference between TaP and another prototypical Weyl semimetal TaAs (20). A prominent distinction is that we found that TaP has a number of additional trivial surface states, closed contours, besides the Fermi arcs, which were not seen in TaAs (20). Because the termination consists of the pnictide (As or P) atoms in both compounds, the additional surface states suggest that the P surface environment is different from that of As. Therefore, it would be interesting to study the evolution of surface state in TaP1−xAsx. It would also be interesting to change the surface environment in TaP via surface deposition or adsorption to study the interplay between the Fermi arc and the trivial surface states. In certain conditions, a topological Fermi arc and a trivial surface state can switch their roles, whereas the constraint placed by topology, that the net number of topological Fermi arcs cannot change, must be met.

We summarize our experimentally practical method for demonstrating Fermi arcs and measuring the topological invariants of Weyl semimetals, as proposed in this study. We choose a closed path in k-space and subtract the number of right-moving modes from the number of left-moving modes. The result equals the total chiral charge of the Weyl nodes enclosed by the path. In real experiments, one should consider the sharpness of the features and the distance between the Weyl nodes in different regions of the BZ and choose the k-path on the basis of these factors. In summary, we have presented systematic ARPES data that reveals the bulk and surface electronic structure of the Weyl semimetal candidate TaP. Our results have identified TaP as the first Weyl semimetal that contains no toxic elements. The nontoxic property is crucial for future research studies and potential applications. We have also demonstrated, for the first time, a systematic experimental methodology that can be more generally applied to discover other Weyl semimetals and to measure their topological invariants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample growth and ARPES measurement techniques

High-quality single crystals of TaAs were grown with the standard chemical vapor transport method reported by Xu et al. (20). High-resolution vacuum ultraviolet ARPES measurements were performed at Beamlines 4.0.3, 10.0.1, and 12.0.1 of the Advanced Light Source at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley, CA); Beamline 5-4 of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (Palo Alto, CA); and Beamline I05 of the Diamond Light Source (Didcot, UK), with the photon energy ranging from 15 to 100 eV. The energy and momentum resolution of the vacuum ultraviolet ARPES instruments was better than 30 meV and 1% of the surface BZ. The SX-ARPES measurements were performed at the Adress Beamline at the Swiss Light Source in the Paul Scherrer Institut (Villigen, Switzerland). The experimental geometry of SX-ARPES has been described by Strocov et al. (26, 27, 29). The sample was cooled down to 12 K to quench the electron-phonon interaction effects, reducing the k-resolved spectral fraction. Our SX photon energy ranged from 300 to 1000 eV. The combined (beamline and analyzer) experimental energy resolution of the SX-ARPES measurements varied between 40 and 80 meV. The angular resolution of the SX-ARPES analyzer was 0.07°. Samples were cleaved in situ under a vacuum condition better than 5 × 10−11 torr at all beamlines.

Computational calculation methods

First-principles calculations were performed by the OPENMX code on the basis of norm-conserving pseudopotentials generated with multireference energies and optimized pseudoatomic basis functions within the framework of the generalized gradient approximation of density functional theory (31). SOC was incorporated through j-dependent pseudopotentials. For each Ta atom, three, two, two, and one optimized radial function were allocated for the s, p, d, and f orbitals (s3p2d2f1), respectively, with a cutoff radius of 7 bohr. For each P atom, s3p3d3f2 was adopted with a cutoff radius of 9 bohr. A regular mesh of 1000 rydberg in real space was used for the numerical integrations and for the solution of the Poisson equation. A k point mesh of 17 × 17 × 5 for the conventional unit cell was used, and experimental lattice parameters were adopted in the calculations. Symmetry-respecting Wannier functions for the P p and Ta d orbitals were constructed without performing the procedure for maximizing localization, and a real-space tight-binding Hamiltonian was obtained (32). This Wannier function–based tight-binding model was used to obtain the surface states by the recursive Green function method.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge J. D. Denlinger, S. K. Mo, A. V. Fedorov, M. Hashimoto, M. Hoesch, T. Kim, and V. N. Strocov for their beamline assistance at the Advanced Light Source, the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, the Diamond Light Source, and the Swiss Light Source. We also thank D. Huse, I. Klebanov, A. Polyakov, P. Steinhardt, H. Verlinde, and A. Vishwanath for discussions. R.S. and H.L. acknowledge visiting scientist support from Princeton University. Funding: Work at Princeton University and Princeton-led synchrotron-based ARPES measurements were supported by the by U.S. DOE/BES under DE-FG-02-05ER46200. Single-crystal growth was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (grant nos. 2013CB921901 and 2014CB239302), and characterization was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundations>’ Emergent Phenomena in Quantum Systems Initiative through grant GBMF4547 (M.Z.H.). First-principles band structure calculations at the National University of Singapore were supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF), Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore, under its NRF fellowship (NRF award no. NRF-NRFF2013-03). T.-R.C. and H.-T.J. were supported by the National Science Council, Taiwan. H.-T.J. also thanks the National Center for High-Performance Computing, Computer and Information Network Center National Taiwan University, and National Center for Theoretical Sciences, Taiwan, for technical support. The work at Northeastern University was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences grant number DE-FG02-07ER46352, and benefited from Northeastern University’s Advanced Scientific Computation Center (ASCC) and the NERSC supercomputing center through DOE grant number DE-AC02-05CH11231. F.C. acknowledges the support provided by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, under project no. 102-2119-M-002-004. Author contributions: S.-Y.X., I.B., N.A., D.S.S., and G.B. conducted the ARPES experiments with assistance from H.Z., P.P.S., M.L.P., V.N.S., and M.Z.H.; C.G., C.Z., Z.Y., H. Lu, R.S., F.C., and S.J. grew the single-crystal samples; G.C., T.-R.C., C.-C.L., S.-M.H., C.-H.H., H.-T.J., A.B., and H. Lin performed first-principles band structure calculations; T.N. performed theoretical analyses; M.Z.H. was responsible for the overall direction, planning, and integration among different research units. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors at M.Z.H. (mzhasan@princeton.edu).

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Wilczek F., Why are there analogies between condensed matter and particle theory? Phys. Today 51, 11–13 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 2.G. E. Volovik, The Universe in a Helium Droplet (Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geim A. K., Novoselov K. S., The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 183–191 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasan M. Z., Kane C. L., Colloquium: Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qi X.-L., Zhang S.-C., Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 6.M. Z. Hasan, S.-Y. Xu, M. Neupane, Topological insulators, topological crystalline insulators, topological Kondo insulators, and topological semimetals, in Topological Insulators: Fundamentals and Perspectives, F. Ortmann, S. Roche, S. O. Valenzuela, Eds. (John Wiley & Sons, Weinheim, Germany, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weyl H., Elektron und gravitation. I. Z. Phys. 56, 330–352 (1929). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murakami S., Phase transition between the quantum spin Hall and insulator phases in 3D: Emergence of a topological gapless phase. New J. Phys. 9, 356 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wan X., Turner A. M., Vishwanath A., Savrasov S. Y., Topological semimetal and fermi-arc surface states in the electronic structure of pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 83, 205101 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balents L., Viewpoint: Weyl electrons kiss. Physics 4, 36 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burkov A. A., Balents L., Weyl semimetal in a topological insulator multilayer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 127205 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu S.-Y., Liu C., Kushwaha S. K., Sankar R., Krizan J. W., Belopolski I., Neupane M., Bian G., Alidoust N., Chang T.-R., Jeng H.-T., Huang C.-Y., Tsai W.-F., Lin H., Shibayev P. P., Chou F.-C., Cava R. J., Hasan M. Z., Observation of Fermi arc surface states in a topological metal. Science 347, 294–298 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosur P., Friedel oscillations due to Fermi arcs in Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 86, 195102 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ojanen T., Helical Fermi arcs and surface states in time-reversal invariant Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 87, 245112 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potter A. C., Kimchi I., Vishwanath A., Quantum oscillations from surface Fermi arcs in Weyl and Dirac semimetals. Nat. Commun. 5, 5161 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosur P., Dai X., Fang Z., Qi X.-L., Time-reversal-invariant topological superconductivity in doped Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 90, 045130 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bednik G., Zyuzin A. A., Burkov A. A., Superconductivity in Weyl metals. Phys. Rev. B 92, 035153 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang S.-M., Xu S.-Y., Belopolski I., Lee C.-C., Chang G., Wang B., Alidoust N., Bian G., Neupane M., Zhang C., Jia S., Bansil A., Lin H., Hasan M. Z., A Weyl Fermion semimetal with surface Fermi arcs in the transition metal monopnictide TaAs class. Nat. Commun. 6, 7373 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weng H., Fang C., Fang Z., Bernevig B. A., Dai X., Weyl semimetal phase in noncentrosymmetric transition-metal monophosphides. Phys. Rev. X 5, 011029 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu S.-Y., Belopolski I., Alidoust N., Neupane M., Bian G., Zhang C., Sankar R., Chang G., Yuan Z., Lee C.-C., Huang S.-M., Zheng H., Ma J., Sanchez D. S., Wang B., Bansil A., Chou F., Shibayev P. P., Lin H., Jia S., Hasan M. Z., Discovery of a Weyl fermion semimetal and topological Fermi arcs. Science 349, 613–617 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu L., Wang Z., Ye D., Ran L., Fu L., Joannopoulos J. D., Soljačić M., Experimental observation of Weyl points. Science 349, 622–624 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv B. Q. Weng H. M., Fu B. B., Wang X. P., Miao H., Ma J., Richard P., Huang X. C., Zhao L. X., Chen G. F., Fang Z., Dai X., Qian T., Ding H., Experimental discovery of Weyl semimetal TaAs. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031013 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lv B. Q., Xu N., Weng H. M., Ma J. Z., Richard P., Huang X. C., Zhao L. X., Chen G. F., Matt C. E., Bisti F., Strokov V. N., Mesot J., Fang Z., Dai X., Qian T., Shi M., Ding H., Observation of Weyl nodes in TaAs. Nat. Phys. 11, 724–727 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu S.-Y. Alidoust N., Belopolski I., Yuan Z., Bian G., Chang T.-R., Zheng H., Strokov V., Sanchez D. S., Chang G., Zhang C., Mou D., Wu Y., Huang L., Lee C.-C., Huang S.-M., Wang B., Bansil A., Jeng H.-T., Neupert T., Kaminski A., Lin H., Jia S., Hasan M. Z., Discovery of a Weyl fermion state with Fermi arcs in niobium arsenide. Nat. Phys. 11, 748–754 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang L. X., Liu Z. K., Sun Y., Peng H., Yang H. F., Zhang T., Zhou B., Zhang Y., Guo Y. F., Rahn M., Prabhakaran D., Hussain Z., Mo S.-K., Felser C., Yan B., Chen Y. L., Weyl semimetal phase in the non-centrosymmetric compound TaAs. Nat. Phys. 11, 728–732 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strocov V. N., Kobayashi M., Wang X., Lev L. L., Krempasky J., Rogalev V. V., Schmitt T., Cancellieri C., Reinle-Schmitt M. L., Soft-X-ray ARPES at the Swiss Light Source: From 3D materials to buried interfaces and impurities. Synchrotron Radiat. News 27, 31–40 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strocov V. N., Wang X., Shi M., Kobayashi M., Krempasky J., Hess C., Schmitt T., Patthey L., Soft-X-ray ARPES facility at the ADRESS beamline of the SLS: Concepts, technical realisation and scientific applications. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 21, 32–44 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willerströem J. O., Stacking disorder in NbP, TaP, NbAs and TaAs. J. Less-Common Met. 99, 273–283 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strocov V. N., Intrinsic accuracy in 3-dimensional photoemission band mapping. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 130, 65–78 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu N., Weng H. M., Lv B. Q., Matt C., Park J., Bisti F., Strocov V. N., Gawryluk D., Pomjakushina E., Conder K., Plumb N. C., Radovic M., Autès G., Yazyev O. V., Fang Z., Dai X., Aeppli G., Qian T., Mesot J., Ding H., Shi M., Observation of Weyl nodes and Fermi arcs in TaP. Mater. Sci. arXiv:1507.03983 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perdew J. P., Burke K., Ernzerhof M., Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weng H., Ozaki T., Terakura K., Revisiting magnetic coupling in transition-metal-benzene complexes with maximally localized Wannier functions. Phys. Rev. B 79, 235118 (2009). [Google Scholar]