Abstract

Background

US hospital discharge datasets typically report facility charges (ie, room and board), excluding professional fees (ie, attending physicians’ charges).

Objectives

We aimed to estimate professional fee ratios (PFR) by year and clinical diagnosis for use in cost analyses based on hospital discharge data.

Subjects

The subjects consisted of a retrospective cohort of Truven Health MarketScan 2004–2012 inpatient admissions (n = 23,594,605) and treat-and-release emergency department (ED) visits (n = 70,771,576).

Measures

PFR per visit was assessed as total payments divided by facility-only payments.

Research Design

Using ordinary least squares regression models controlling for selected characteristics (ie, patient age, comorbidities, etc.), we calculated adjusted mean PFR for admissions by health insurance type (commercial or Medicaid) per year overall and by Major Diagnostic Category (MDC), Diagnostic Related Group, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Clinical Classification Software, and primary International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis, and for ED visits per year overall and by MDC and primary ICD-9-CM diagnosis.

Results

Adjusted mean PFR for 2012 admissions, including preceding ED visits, was 1.264 (95% CI, 1.264, 1.265) for commercially insured admissions (n = 2,614,326) and 1.177 (1.176, 1.177) for Medicaid admissions (n = 816,503), indicating professional payments increased total per-admission payments by an average 26.4% and 17.7%, respectively, above facility-only payments. Adjusted mean PFR for 2012 ED visits was 1.286 (1.286, 1.286) for commercially insured visits (n = 8,808,734) and 1.440 (1.439, 1.440) for Medicaid visits (n = 2,994,696). Supplemental tables report 2004–2012 annual PFR estimates by clinical classifications.

Conclusions

Adjustments for professional fees are recommended when hospital facility-only financial data from US hospital discharge datasets are used to estimate health care costs.

Keywords: costs and cost analysis, economics, hospital, hospital charges

Hospital discharge data are routinely collected in most US states and used extensively in epidemiologic and economic analyses that aim to inform health policy. Discharge datasets typically capture information for all patients discharged from acute care hospitals and report patients’ demographic characteristics, diagnoses, procedures, payer type, and hospital facility charges.1 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality provides publicly available, aggregated hospital inpatient and emergency department (ED) discharge data and national samples through the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP).2

Hospital discharge datasets are commonly used for cost analysis, health services research, and population health surveillance.3,4 The major strengths of hospital discharge data include public availability, low cost, and population representativeness. However, key information on diagnoses and procedures, comorbidities, race/ethnicity, and payer is not standardized across hospitals and states and may be underreported.1,5,6

Hospital discharge datasets have 2 other notable limitations for cost analyses. The first is that such datasets report hospitals’ billed charges rather than payments (or revenue) received.4 Hospital discharge datasets are thus different from medical claims datasets, which report payments to hospitals and providers. Cost-to-charge ratios (CCR) from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services can be applied to charges reported in discharge datasets to estimate hospital costs from reported charges.5,7 CCR may produce a reasonable proxy for payments hospitals receive.8 The second disadvantage of hospital discharge datasets is that they typically report only facility charges billed by hospitals, excluding physician, or professional fees.4,9 Facility charges include, for example, room and board fees, and all other payments to hospitals.10 Professional charges reflect services by physicians and other skilled health care professionals licensed for independent practice, including many clinicians treating patients in hospitals.10

A lack of professional fees is often identified as a limitation of cost analyses based on hospital discharge data.11,12 Some cost studies using such data have applied professional fee estimates generated from separate data sources.13,14 Limited information suggests facility-only costs might underestimate the full cost of hospital visits by 20%–25%.14,15 We aimed to estimate professional fee ratios (PFR) for inpatient admissions and treat-and-release ED (hereafter ED) visits for use in cost analyses based on hospital discharge data.

METHODS

We used medical claims data to estimate PFR for hospital discharge data. We posited that, consistent with limited previous estimates, professional fees might contribute an additional 20%–25% on top of facility fees to total hospital-based service costs. We identified admissions (including those originating in the ED) and ED visits among patients with commercial or Medicaid insurance reported in Truven Health MarketScan 2004–2012 databases. Market-Scan reports paid insurance claims and encounters from a selection of large employers, health plans, and government and public organizations, including approximately a dozen Medicaid state agencies.16 MarketScan reports clinical diagnoses and associated payments to health care providers; charges submitted by providers are not reported.17 The study period reflects availability of MarketScan variables that distinguish between facility and professional payments,17 as well as a sufficient number of observations to estimate annual PFR stratified by selected clinical classifications [ie, Diagnostic Related Group (DRG)]. The primary outcome measures were associations between PFR and selected patient and service characteristics and estimated PFR per hospital admission or ED visit annually by insurance type (ie, commercial and Medicaid) and selected clinical classifications. Secondary outcome measures were annual overall adjusted mean PRF for admissions and ED visits by insurance type. Cost data are reported as 2012 USD using the Price Indexes for Personal Consumption Expenditures by Function from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis.18

PFR Definition

PFR was defined as the ratio of total payments to facility-only payments per admission or ED visit. On the basis of financial variables available in MarketScan, we calculated PFR per admission as total payment divided by the facility-only payment to the hospital.17 We calculated PFR per ED visit as the sum of facility and professional payments for ED services divided by the facility-only payment. The resulting PFR estimates were designed to be multiplied by facility-only cost estimates from hospital discharge datasets to yield a total cost of care per visit. For example, if the estimated facility cost of a patient’s admission reported in a hospital discharge dataset is $1000 and the corresponding estimated PFR for that patient’s clinical diagnosis that year is 1.240, the total estimated direct medical cost of the admission could be calculated as $1240.

Clinical and Payment Classifications

MarketScan reports patients’ clinical diagnoses based on administrative codes, including Major Diagnostic Category (MDC) (inpatient and ED), DRG (inpatient), and primary and other International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnoses (inpatient and ED). We applied HCUP Clinical Classifications Software (HCUP-CCS) to report PFR by single-level HCUP-CCS (inpatient).19 To ensure sufficient sample sizes for PFR estimates stratified by year and diagnosis, we assessed 3-digit, rather than the more specific 5-digit, ICD-9-CM classifications. We identified ED services among admitted patients using recommended criteria for the data source.17 We combined patients’ inpatient (and preceding ED, where applicable) and outpatient ED payment records and clinical information for services beginning on the same date and attributed the sum of payments and all associated clinical data to a single admission or ED visit.17 Where >1 ICD-9-CM diagnosis was reported as the primary diagnosis for an admission (< 0.1% of analyzed admissions), we assigned the first-listed primary diagnosis as the primary diagnosis. We identified the primary diagnosis for ED visits based on the diagnosis to which facility payments were attributed. ED visits with >1 primary diagnosis associated with facility payments (< 0.5% of the sample) were excluded.

Sample Selection

We excluded admissions and ED visits with missing diagnostic information (ie, MDC, DRG, or ICD-9-CM primary diagnosis). We excluded admissions and ED visits with illogical diagnostic values (ie, E-code as primary ICD-9-CM diagnosis, or >1 DRG or MDC). We excluded admissions and ED visits with illogical payments (ie, negative or zero total payments or facility payments, or total payments that were less than reported facility payments).

We observed some admissions and ED visits with what appeared to be unreasonably low hospital facility payments, which created extreme PFR outliers; for example, facility payment <$1 for a multiday admission with professional payments of >$1000. The median inpatient facility payment per day was $2858 for commercially insured patients and $1570 for Medicaid patients over the study period. We excluded records with the lowest 1% of facility payments per hospitalized day (ie, <$298 for commercially insured patients and <$105 for Medicaid patients). The median ED treat-and-release facility payment was $532 for commercially insured patients and $139 for Medicaid patients. We excluded records with the lowest 1% of facility payments for ED visits (ie, <$32 for commercially insured patients and <$17 for Medicaid patients).

Patient and Service Characteristics

To estimate adjusted mean PFR we used multivariable regression models to control for factors associated with health care utilization and costs, and therefore hypothesized to influence professional fees: patient age (continuous variable), sex (dichotomous), race/ethnicity (categorical), health insurance plan type [ie, health maintenance organization (HMO), etc.; categorical], ED services preceding an admission (dichotomous), number of comorbidities (ie, hypertension, diabetes, etc.; continuous), surgery (dichotomous), treatment of medical complications (dichotomous), length of inpatient stay, discharge status (ie, to home, etc.; categorical), and the hospital’s US state or regional location (ie, Connecticut or Northeast region, etc.; categorical).20

Age for Medicaid patients was based on patients’ year of birth. Race/ethnicity was available only for Medicaid patients. Adult (18 y old and above) comorbidities were defined by HCUP Comorbidity Software, Version 3.7,3,21 which identifies coexisting medical conditions that are not the primary reason for a hospital admission. This comorbidity classification relied on DRG information, which is not applicable to ED visits; therefore, only the inpatient PFR models controlled for comorbidities. For admissions among children and adolescents (below 18 y old), we also included as comorbidities selected childhood chronic conditions (developmental disabilities and congenital defects) defined by ICD-9-CM codes (see Table 1 notes).22 In models based on MDC, CCS, and primary ICD-9-CM diagnosis, we included a variable for surgery based on the accompanying DRG (which is classified as surgical or medical) in the admission models or based on Current Procedural Terminology codes indicating surgery (10000–69999) in ED visit models.23 Admission models controlled for treatment of medical complications, defined by ICD-9-CM codes (see Table 1 notes).20 Hospital location was reported only for commercially insured admissions and ED visits; hospital state was reported for admissions but only region was reported for ED visits. Hospital state was included only in aggregate models of commercially insured admissions by year; in models of individual clinical classifications by year, smaller sample sizes dictated the use of hospital region, instead. Health insurance plan type, length of inpatient stay, and discharge status were analyzed as reported in the data source.

TABLE 1.

Summary Statistics and Multivariable Models of Professional Fee Ratios for Inpatient Admissions by Insurance Type, 2012†

| Commercial Insurance (n = 2,614,326) | Medicaid (n = 816,503) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Measure or Category | n (%) | β (95% CI) | n (%) | β (95% CI) |

| PFR | Mean (SD) (range) | 1.264 (0.375) (1–137) | 1.264 (1.264, 1.265) | 1.177 (0.257) (1–16) | 1.177 (1.176, 1.177) |

| Patient age‡ | Mean (SD) (range) (y) | 36.281 (19.966) (0–64) | 0.000 (0.000, 0.000)* | 31.398 (25.379) (0–90) | −0.001 (−0.001, −0.001)* |

| Patient sex | Male | 1,001,812 (38.3) | Reference | 305,461 (37.4) | Reference |

| Female | 1,612,514 (61.7) | −0.001 (−0.002, 0.000) | 511,042 (62.6) | −0.009 (−0.010, −0.008)* | |

| Patient race/ethnicity | White | NA | NA | 405,866 (49.7) | Reference |

| Black | NA | NA | 244,341 (29.9) | −0.023 (−0.024, −0.022)* | |

| Hispanic | NA | NA | 58,507 (7.2) | −0.012 (−0.015, −0.010)* | |

| Other | NA | NA | 107,789 (13.2) | −0.034 (−0.035, −0.032)* | |

| Patient’s health insurance plan type | COMP | 47,824 (1.8) | Reference | 658,620 (80.7) | Reference |

| EPO | 54,241 (2.1) | 0.013 (0.009, 0.017)* | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

| HMO | 273,927 (10.5) | 0.013 (0.011, 0.016)* | 138,021 (16.9) | 0.029 (0.027, 0.031)* | |

| POS | 152,434 (5.8) | 0.011 (0.008, 0.014)* | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

| PPO | 1,675,683 (64.1) | 0.012 (0.010, 0.015)* | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

| POS with capitation | 9751 (0.4) | 0.013 (0.006, 0.020)* | 18,849 (2.3) | −0.142 (−0.144, −0.141)* | |

| CDHP | 96,756 (3.7) | 0.016 (0.014, 0.019)* | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

| HDHP | 77,775 (3.0) | 0.009 (0.006, 0.012)* | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

| Unknown | 225,935 (8.6) | 0.033 (0.030, 0.035)* | 1013 (0.1) | −0.015 (−0.037, 0.007) | |

| Emergency department | Yes | 1,029,871 (39.4) | 0.004 (0.003, 0.005)* | 264,670 (32.4) | 0.011 (0.010, 0.012)* |

| No. comorbidities§ | 0 | 1,085,946 (41.5) | Reference | 248,973 (30.5) | Reference |

| 1 | 756,939 (29.0) | 0.009 (0.008, 0.010)* | 215,376 (26.4) | 0.015 (0.013, 0.016)* | |

| 2 | 392,112 (15.0) | 0.009 (0.007, 0.010)* | 130,820 (16.0) | 0.014 (0.012, 0.016)* | |

| 3+ | 379,329 (14.5) | 0.010 (0.008, 0.011)* | 221,334 (27.1) | 0.010 (0.008, 0.011)* | |

| Medical complications‖ | Yes | 80,371 (3.1) | −0.005 (−0.007, −0.003)* | 16,133 (2.0) | −0.002 (−0.006, 0.003) |

| Length of stay | Mean (SD) (range) (d) | 4.021 (6.423) (1–514) | −0.002 (−0.002, −0.002)* | 5.186 (11.719) (1–585) | 0.000 (0.000, 0.000)* |

| Discharge status | Home | 2,336,008 (89.4) | Reference | 706,133 (86.5) | Reference |

| Transfer | 105,146 (4.0) | 0.020 (0.018, 0.022)* | 76,446 (9.4) | 0.020 (0.018, 0.022)* | |

| Died | 15,987 (0.6) | −0.001 (−0.005, 0.003) | 9949 (1.2) | −0.009 (−0.014, −0.004)* | |

| Other | 26,065 (1.0) | −0.025 (−0.028, −0.022)* | 19,200 (2.4) | −0.056 (−0.060, −0.053)* | |

| Unknown | 131,120 (5.0) | 0.028 (0.026, 0.030)* | 4775 (0.6) | 0.029 (0.022, 0.036)* | |

| Surgery | Yes | 907,380 (34.7) | NA | 142,790 (17.5) | NA |

| Hospital regional location | Northeast | 493,070 (18.9) | NA | NA | NA |

| North central | 656,119 (25.1) | NA | NA | NA | |

| South | 954,951 (36.5) | NA | NA | NA | |

| West | 457,163 (17.5) | NA | NA | NA | |

| Unknown | 53,023 (2.0) | NA | NA | NA | |

| US state¶ | All | See SDC | See SDC | NA | NA |

| Clinical diagnosis (DRG)# | All | See SDC | See SDC | NA | NA |

P < 0.05. Estimates are based on ordinary least square regression models with robust SEs. PFR is dependent variable and models include all other listed factors as independent variables.

Model values for 2004–2012 reported in Supplementary Digital Content (SDC) file (SDC Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B2).

Age approximated by reported year of birth for Medicaid patients.

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Comorbidity Software, Version 3.719 and for children and adolescents (< 18 y old), also includes epilepsy/recurrent seizures (ICD-9-CM code 345), developmental delays (ICD-9-CM code 315), other nervous symptoms (ICD-9-CM code 781), congenital anomalies (ICD-9-CM-codes 740–759), conditions originating in the perinatal period (ICD-9-CM codes 760–779) and other chronic conditions (ICD-9-CM codes 299, 343, 317–319, 677, 369, 389).20

Complications defined as the following secondary ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes on the admission record: 349.0, 349.1, 429.4, 512.1, 519.0, 564.2, 564.3, 564.4, 569.6, 579.3, 909.3, 995.4, 997.0, 997.1, 997.2, 997.3, 997.4, 997.5, 997.60, 997.61, 997.62, 997.69, 997.9, 998.0, 998.1, 998.2, 998.3, 998.4, 998.5, 998.6, 998.7, 998.8, 998.81, 998.82, 998.89, 998.9, 999.0, 999.1, 999.2, 999.3, 999.4, 999.5, 999.6, 999.7, 999.8, 999.9.19

Estimates for this large category suppressed. Estimates reported in accompanying SDC file (SDC Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B2). US state included in multivariable models of all observations by year (eg, depicted in this table for 2012 and in SDC Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B2 for all study years). US region included in multivariable models of individual clinical diagnoses (see SDC Table 3, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B4 and SDC Table 4, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B5).

Estimates for this large category (n > 800 separate DRG classifications) suppressed. Estimates reported in accompanying SDC File (SDC Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B2).

CDHP indicates Consumer-Driven Health Plan; CI, confidence interval; COMP, Comprehensive; DRG, Diagnostic Related Group; EPO, Exclusive Provider Organization; HDHP, High Deductible Health Plan; HMO, Health Maintenance Organization; NA, not applicable; PFR, professional fee ratios; POS, Non-Capitated Point-of-Service; PPO, Preferred Provider Organization.

Analysis

Using admissions and ED visits as the units of analysis and PFR as the dependent variable, we first assessed associations between PFR and patient and service characteristics described previously using multivariable regression models. We then estimated adjusted mean PFR—as well as associated SE and 95% confidence intervals (CI)—calculated as the mean value of the model-predicted PFR for each admission or visit using Stata 13 (College Station, TX) margins program.24 Among admissions, we estimated adjusted mean PFR first overall, stratified by year and insurance type and controlling for DRG, and then we estimated separate models for each clinical classification (ie, MDC, DRG, HCUP-CCS, and primary ICD-9-CM diagnosis) annually.16,25,26 Among ED visits, we estimated adjusted mean PFR first overall, stratified by year and insurance type and controlling for MDC, and then we estimated separate models for each clinical classification (ie, MDC and primary ICD diagnosis) annually. Adjusted mean PFR estimates (hereafter simply PFR estimates) for clinical classifications with <100 observations are not reported. SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC) was used for sample selection and Stata 13 was used for modeling.

PFR estimates as reported here were designed to be multiplied by facility-only hospital costs to estimate the total direct medical cost of admissions or ED visits based on financial information from hospital discharge data. Because of the computing power and time required for this selected presentation of results (ie, 1 model for each clinical diagnosis, by insurance type, each year—amounting to tens of thousands of models—and reporting estimated PFR per diagnosis and year as the mean value of model-predicted PFR for each admission or visit), we used ordinary least squares regression models with robust SE. Model results and PFR estimates for 2012 are reported in detail below. PFR estimates—as well practical use guidance—for admissions and ED visits 2004–2012 annually overall and by clinical diagnosis are reported below and in the accompanying Supplementary Digital Content (SDC) files (SDC Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B2, SDC Table 2 Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B3, SDC Table 3, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B4, SDC Table 4, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B5, and “How to use professional fee ratio estimates with hospital discharge data,” Supplemental Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B6).

RESULTS

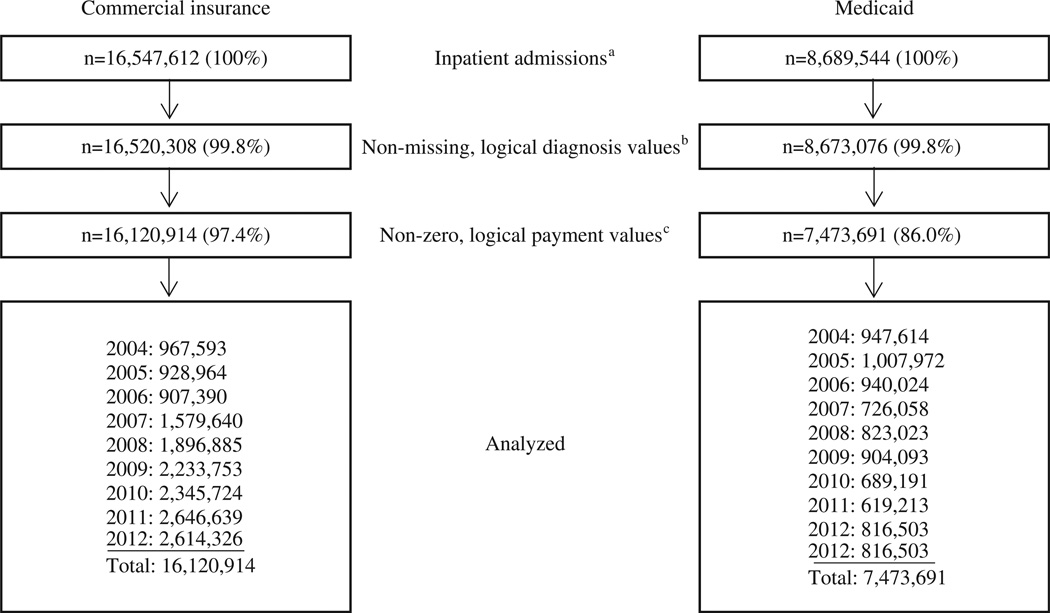

Sample selection is reported in Figures 1 and 2. Included in the analysis were 23,594,605 admissions (16,120,914 commercially insured admissions and 7,473,691 Medicaid admissions) and 70,771,576 treat-and-release ED visits (46,296,227 commercially insured visits and 24,475,349 Medicaid visits). Descriptive information by year is reported in SDC Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B2 and SDC Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B3.

FIGURE 1.

Sample selection for inpatient admissions by insurance type, 2004–2012. aAdmissions excluded if missing patient age, sex, or length of stay. bClinical diagnosis values included: DRG= 1–999; MDC= 0–25; primary 3-digit ICD-9-CM: 001–999 (excluding error values such as “028”), as well as valid V-values. cAdmissions excluded if hospital facility payment $ ≤ 0, total payment $ ≤ 0, or professional fee ratio <1 (ie, suggesting total payment was less than the component hospital facility payment). Admissions with the lowest 1% of hospital facility payments per inpatient day (ie, total facility payment for admission divided by length of stay) excluded. DRG indicates Diagnostic Related Group; MDC, Major Diagnostic Category; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification.

FIGURE 2.

Sample selection for treat-and-release emergency department visits by insurance type, 2004–2012. aVisits excluded if missing patient age or sex. bClinical diagnosis values included: MDC = 0–25; primary 3-digit ICD-9-CM: 001–999 (excluding error values such as “028”), as well as valid V-values. Primary diagnosis with a facility payment was defined as the primary visit diagnosis. Visits with >1 primary diagnosis with an associated facility payment were excluded. cVisits excluded if hospital facility payment $ ≤ 0 or professional payment $ < 0. Visits with the lowest 1% of hospital facility payments excluded. ED indicates emergency department; MDC indicates Major Diagnostic Category; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification.

Among admissions for commercially insured patients, increased patient age was significantly associated with slightly lower PFR (ie, <0.1 percentage point lower per year of increased age) from 2004 to 2009 but was not significant from 2010 to 2012 (see Table 1 below for 2012 model results, see SDC Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B2 for model results for all study years). HMO health plans showed a significant but varied relationship with PFR compared with Comprehensive health plans (ie, plans with no incentive for patients to use particular providers15). Other health plan types generally had significantly higher PFR (ie, 1–3 percentage points higher in 2012) compared with Comprehensive insurance. ED services preceding an inpatient admission and comorbidities were significantly associated with a higher PFR, as was surgery. Treatment of medical complications was associated with a significantly lower PFR, as was length of hospital stay. Admissions for patients who were transferred to another facility had higher PFR compared with patients discharged to home.

Among admissions for Medicaid patients, increased age and female sex were associated with slightly decreased PFR over the study period (see Table 1 below for 2012 model results, see SDC Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B2 for model results for all study years). Admissions among patients with black and other non-Hispanic race/ethnicity had significantly lower PFR compared with white patients, whereas admissions among Hispanic patients had a significant but varied relative relationship with PFR over the study period. ED visits preceding admissions, length of stay, discharge destination, and surgery demonstrated similar relationships to PFR as the commercially insurance models. Compared with Comprehensive health plans, HMO plans had significantly higher PFR and patients with capitated plans had lower PFR over the study period. In the early part of the study period, admissions among patients with comorbidities had lower PFR, whereas in later years PFR was significantly higher. Treatment of medical complications did not demonstrate a consistent and significant association with PFR.

Among ED visits for both commercially insured and Medicaid patients, increased patient age was consistently and significantly associated with lower PFR (see Table 2 below for 2012 model results, see SDC Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B3 for model results for all study years). Female sex demonstrated a significant but varied relationship with PFR among commercially insured ED visits over the study period, but was generally associated with a significantly higher PFR among Medicaid visits. Patients with non-Comprehensive health plan types—whether commercial or Medicaid insurance—demonstrated varied relationships with PFR relative to Comprehensive plans. In the earlier years of the study period, regions outside the Northeast demonstrated significantly higher PFR among commercially insured ED visits, although beginning in 2009 treatment in the West region was consistently and significantly associated with lower PFR compared with the Northeast.

TABLE 2.

Summary Statistics and Multivariable Models of Professional Fee Ratios for Treat-and-Release Emergency Department Visits by Insurance Type, 2012†

| Commercial Insurance (n = 8,808,734) | Medicaid (n = 2,994,696) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Measure or Category | n (%) | β (95% CI) | n (%) | β (95% CI) |

| PFR‡ | Mean (SD) (range) | 1.286 (0.519) (1–576) | 1.286 (1.286, 1.286) | 1.44 (0.559) (1–62) | 1.286 (1.286, 1.286) |

| Patient age§ | Mean (SD) (range) (y) | 32.47 (18.235) (0–64) | −0.001 (−0.001, −0.001)* | 26.635 (21.396) (0–90) | −0.003 (−0.003, −0.003)* |

| Patient sex | Male | 3,848,256 (43.7) | Reference | 1,171,005 (39.1) | Reference |

| Female | 4,960,478 (56.3) | −0.003 (−0.003, −0.002)* | 1,823,691 (60.9) | 0.004 (0.003, 0.006)* | |

| Patient race/ethnicity | White | NA | NA | 1,382,145 (46.2) | Reference |

| Black | NA | NA | 968,044 (32.3) | −0.074 (−0.075, −0.072)* | |

| Hispanic | NA | NA | 189,134 (6.3) | −0.012 (−0.014, −0.009)* | |

| Other | NA | NA | 455,373 (15.2) | −0.084 (−0.086, −0.082)* | |

| Patient’s health insurance plan type | COMP | 141,675 (1.6) | Reference | 2,320,295 (77.5) | Reference |

| EPO | 197,810 (2.2) | −0.055 (−0.059, −0.051)* | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

| HMO | 925,673 (10.5) | 0.004 (0.001, 0.008)* | 540,674 (18.1) | 0.019 (0.017, 0.020)* | |

| POS | 508,603 (5.8) | −0.005 (−0.009, −0.001)* | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

| PPO | 5,594,171 (63.5) | −0.034 (−0.037, −0.030)* | 0 (0.0) | 0.000 (0.000, 0.000)* | |

| POS with capitation | 30,358 (0.3) | −0.020 (−0.024, −0.016)* | 131,393 (4.4) | −0.028 (−0.032, −0.024)* | |

| CDHP | 312,046 (3.5) | −0.028 (−0.035, −0.020)* | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

| HDHP | 260,910 (3.0) | 0.035 (0.031, 0.039)* | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

| Unknown | 837,488 (9.5) | −0.006 (−0.010, −0.002)* | 2334 (0.1) | −0.173 (−0.191, −0.155)* | |

| Surgery | Yes | 2,451,879 (27.8) | 0.029 (0.028, 0.030)* | 306,057 (10.2) | 0.023 (0.020, 0.025)* |

| Hospital regional location‖ | Northeast | 1,736,047 (19.7) | Reference | NA | NA |

| North central | 2,219,598 (25.2) | 0.010 (0.009, 0.012)* | NA | NA | |

| South | 3,304,685 (37.5) | 0.064 (0.063, 0.065)* | NA | NA | |

| West | 1,338,825 (15.2) | −0.020 (−0.021, −0.018)* | NA | NA | |

| Unknown | 209,579 (2.4) | −0.009 (−0.011, −0.007)* | NA | NA | |

| Clinical diagnosis (MDC)¶ | All | See SDC | See SDC | See SDC | See SDC |

P < 0.05. Estimates are based on ordinary least square regression models with robust SEs. PFR is dependent variable and models include all other listed factors as independent variables.

Model values for 2004–2012 reported in Supplementary Digital Content (SDC) file (SDC Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B3).

Model result for PFR is the average of predicted values from all observations in the model, referred to here as the adjusted mean PFR.

Age approximated by reported year of birth for Medicaid patients.

US state location not reported for emergency department visits in the data source.

Estimates for this large category (n = 25 separate MDC classifications) suppressed. Estimates reported in accompanying SDC file (SDC Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B3).

CDHP indicates Consumer-Driven Health Plan; CI, confidence interval; COMP, Comprehensive; EPO, Exclusive Provider Organization; HMO, Health Maintenance Organization; MDC, Major Diagnostic Category; NA, not applicable; PFR, professional fee ratios; POS, Non-Capitated Point-of-Service; PPO, Preferred Provider Organization.

Overall estimated PFR for 2012 admissions, including preceding ED visits, was 1.264 (95% CI, 1.264, 1.265) for commercially insured admissions (n = 2,614,326) and 1.177 (1.176, 1.177) for Medicaid admissions (n = 816,503), indicating professional payments increased total per-admission payments by an average 26.4% and 17.7%, respectively, above facility-only payments (Table 3). Overall estimated mean PFR for 2012 treat-and-release ED visits was 1.286 (1.286, 1.286) for commercially insured visits (n = 8,808,734) and 1.440 (1.439, 1.440) for Medicaid visits (n = 2,994,696). Controlling for selected patient and health service characteristics as well as DRG, the overall estimated PFR per year for commercially insured admissions declined 6% over the study period [from 1.342 (1.341, 1.343) in 2004 to 1.264 (1.264, 1.265) in 2012, significant based on nonoverlapping CIs] (Table 3). The overall estimated PFR for Medicaid admissions declined 3% (Table 3). Overall estimated PFR for ED visits also declined significantly for both commercially insured and Medicaid visits (13% and 3% declines, respectively) from 2004 to 2012 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Adjusted Mean Annual Professional Fee Ratios for Inpatient Admissions and Treat-and-Release Emergency Department Visits by Health Insurance Type, All Diagnoses, 2004–2012

| Inpatient Admissions | Treat-and-Release Emergency Department Visits | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Commercial Insurance | n | Medicaid | n | Commercial Insurance | n | Medicaid | n |

| 2004 | 1.342 (1.341, 1.343) | 967,593 | 1.211 (1.207, 1.214) | 947,614 | 1.452 (1.451, 1.453) | 2,226,016 | 1.490 [1.489,1.490] | 3,060,112 |

| 2005 | 1.336 (1.335, 1.336) | 928,964 | 1.209 (1.207, 1.212) | 1,007,972 | 1.406 (1.405, 1.407) | 2,137,532 | 1.540 [1.539,1.541] | 3,630,717 |

| 2006 | 1.336 (1.335, 1.337) | 907,390 | 1.196 (1.195, 1.197) | 940,024 | 1.416 (1.415, 1.418) | 2,317,367 | 1.552 [1.551,1.553] | 3,316,639 |

| 2007 | 1.334 (1.334, 1.335) | 1,579,640 | 1.158 (1.158, 1.159) | 726,058 | 1.457 (1.456, 1.457) | 4,091,440 | 1.531 [1.530,1.532] | 2,114,851 |

| 2008 | 1.308 (1.307, 1.308) | 1,896,885 | 1.166 (1.165, 1.166) | 823,023 | 1.422 (1.421, 1.422) | 5,064,919 | 1.488 [1.487,1.489] | 2,438,195 |

| 2009 | 1.294 (1.294, 1.295) | 2,233,753 | 1.159 (1.158, 1.159) | 904,093 | 1.438 (1.438, 1.439) | 6,165,101 | 1.477 [1.476,1.477] | 3,010,863 |

| 2010 | 1.284 (1.284, 1.285) | 2,345,724 | 1.154 (1.154, 1.155) | 689,191 | 1.371 (1.370, 1.372) | 6,962,574 | 1.453 [1.452,1.454] | 2,051,037 |

| 2011 | 1.269 (1.269, 1.270) | 2,646,639 | 1.143 (1.142, 1.143) | 619,213 | 1.294 (1.294, 1.295) | 8,522,544 | 1.444 [1.443,1.445] | 1,858,239 |

| 2012 | 1.264 (1.264, 1.265) | 2,614,326 | 1.177 (1.176, 1.177) | 816,503 | 1.286 (1.286, 1.286) | 8,808,734 | 1.440 [1.439,1.440] | 2,994,696 |

Data are average predicted professional fee ratios (95% confidence interval) from multivariable linear models adjusted for all variables listed in Table 1 (admissions) and Table 2 (emergency department visits). All SEs < 0.001 except Medicaid inpatient 2004 (SE = 0.002) and 2005 (SE = 0.001) and commercial treat-and-release emergency department 2006 (SE = 0.001).

PFR estimates for the top 100 commercially insured inpatient admissions in the data source by DRG in 2012 based on number of admissions are reported in Table 4. PFR estimates by all years and clinical classifications are reported in SDC Table 3, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B4 (admissions) and SDC Table 4, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B5 (ED visits).

TABLE 4.

Professional Fee Ratio Estimates by Top 100 DRG, Commercially Insured Inpatient Admissions, 2012

| DRG | Description | n | Rank by Sample Size |

PFR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | CRANIOTOMY & ENDOVASCULAR INTRACRANIAL PROCEDURES W MCC | 5950 | 77 | 1.287 (1.277, 1.298) |

| 64 | INTRACRANIAL HEMORRHAGE OR CEREBRAL INFARCTION W MCC | 6407 | 73 | 1.165 (1.160, 1.169) |

| 65 | INTRACRANIAL HEMORRHAGE OR CEREBRAL INFARCTION W CC | 7873 | 60 | 1.153 (1.151, 1.156) |

| 69 | TRANSIENT ISCHEMIA | 6736 | 71 | 1.178 (1.174, 1.182) |

| 101 | SEIZURES W/O MCC | 14,254 | 30 | 1.202 (1.198, 1.206) |

| 103 | HEADACHES W/O MCC | 9212 | 46 | 1.147 (1.144, 1.150) |

| 153 | OTITIS MEDIA & URI W/O MCC | 7714 | 62 | 1.125 (1.122, 1.128) |

| 164 | MAJOR CHEST PROCEDURES W CC | 5523 | 82 | 1.273 (1.267, 1.279) |

| 176 | PULMONARY EMBOLISM W/O MCC | 8916 | 49 | 1.115 (1.113, 1.117) |

| 189 | PULMONARY EDEMA & RESPIRATORY FAILURE | 6316 | 75 | 1.116 (1.114, 1.118) |

| 190 | CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE W MCC | 7428 | 66 | 1.122 (1.120, 1.125) |

| 191 | CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE W CC | 5665 | 79 | 1.119 (1.117, 1.122) |

| 193 | SIMPLE PNEUMONIA & PLEURISY W MCC | 8304 | 56 | 1.133 (1.130, 1.135) |

| 194 | SIMPLE PNEUMONIA & PLEURISY W CC | 17,823 | 22 | 1.115 (1.113, 1.117) |

| 195 | SIMPLE PNEUMONIA & PLEURISY W/O CC/MCC | 12,173 | 35 | 1.104 (1.102, 1.105) |

| 202 | BRONCHITIS & ASTHMA W CC/MCC | 15,024 | 28 | 1.129 (1.127, 1.132) |

| 203 | BRONCHITIS & ASTHMA W/O CC/MCC | 16,665 | 23 | 1.106 (1.104, 1.108) |

| 234 | CORONARY BYPASS W CARDIAC CATH W/O MCC | 5632 | 80 | 1.212 (1.207, 1.218) |

| 247 | PERC CARDIOVASC PROC W DRUG-ELUTING STENT W/O MCC | 16,016 | 26 | 1.113 (1.110, 1.116) |

| 249 | PERC CARDIOVASC PROC W NON-DRUG-ELUTING STENT W/O MCC | 8359 | 54 | 1.127 (1.124, 1.131) |

| 251 | PERC CARDIOVASC PROC W/O CORONARY ARTERY STENT W/O MCC | 6829 | 70 | 1.173 (1.165, 1.181) |

| 282 | ACUTE MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION, DISCHARGED ALIVE W/O CC/MCC | 4802 | 97 | 1.146 (1.141, 1.150) |

| 287 | CIRCULATORY DISORDERS EXCEPT AMI, W CARD CATH W/O MCC | 18,175 | 20 | 1.142 (1.139, 1.145) |

| 292 | HEART FAILURE & SHOCK W CC | 5983 | 76 | 1.137 (1.134, 1.140) |

| 300 | PERIPHERAL VASCULAR DISORDERS W CC | 4742 | 98 | 1.130 (1.127, 1.134) |

| 305 | HYPERTENSION W/O MCC | 4715 | 99 | 1.142 (1.139, 1.146) |

| 309 | CARDIAC ARRHYTHMIA & CONDUCTION DISORDERS W CC | 7949 | 59 | 1.158 (1.154, 1.162) |

| 310 | CARDIAC ARRHYTHMIA & CONDUCTION DISORDERS W/O CC/MCC | 15,066 | 27 | 1.153 (1.150, 1.155) |

| 312 | SYNCOPE & COLLAPSE | 9035 | 48 | 1.166 (1.162, 1.170) |

| 313 | CHEST PAIN | 18,180 | 19 | 1.152 (1.149, 1.154) |

| 329 | MAJOR SMALL & LARGE BOWEL PROCEDURES W MCC | 8245 | 57 | 1.192 (1.188, 1.197) |

| 330 | MAJOR SMALL & LARGE BOWEL PROCEDURES W CC | 18,355 | 18 | 1.228 (1.225, 1.231) |

| 331 | MAJOR SMALL & LARGE BOWEL PROCEDURES W/O CC/MCC | 7789 | 61 | 1.247 (1.242, 1.253) |

| 343 | APPENDECTOMY W/O COMPLICATED PRINCIPAL DIAG W/O CC/MCC | 18,361 | 17 | 1.286 (1.279, 1.293) |

| 372 | MAJOR GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS & PERITONEAL INFECTIONS W CC | 4696 | 100 | 1.125 (1.122, 1.128) |

| 378 | G.I. HEMORRHAGE W CC | 8829 | 50 | 1.189 (1.186, 1.193) |

| 386 | INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE W CC | 5867 | 78 | 1.154 (1.151, 1.157) |

| 389 | G.I. OBSTRUCTION W CC | 6879 | 69 | 1.135 (1.132, 1.138) |

| 390 | G.I. OBSTRUCTION W/O CC/MCC | 7623 | 63 | 1.127 (1.124, 1.130) |

| 391 | ESOPHAGITIS, GASTROENT & MISC DIGEST DISORDERS W MCC | 9424 | 43 | 1.164 (1.161, 1.167) |

| 392 | ESOPHAGITIS, GASTROENT & MISC DIGEST DISORDERS W/O MCC | 57,167 | 8 | 1.146 (1.145, 1.148) |

| 394 | OTHER DIGESTIVE SYSTEM DIAGNOSES W CC | 7366 | 67 | 1.150 (1.146, 1.153) |

| 417 | LAPAROSCOPIC CHOLECYSTECTOMY W/O C.D.E. W MCC | 4815 | 96 | 1.250 (1.243, 1.258) |

| 418 | LAPAROSCOPIC CHOLECYSTECTOMY W/O C.D.E. W CC | 14,253 | 31 | 1.296 (1.289, 1.303) |

| 419 | LAPAROSCOPIC CHOLECYSTECTOMY W/O C.D.E. W/O CC/MCC | 9342 | 44 | 1.265 (1.257, 1.272) |

| 439 | DISORDERS OF PANCREAS EXCEPT MALIGNANCY W CC | 8397 | 53 | 1.137 (1.134, 1.140) |

| 440 | DISORDERS OF PANCREAS EXCEPT MALIGNANCY W/O CC/MCC | 8155 | 58 | 1.129 (1.127, 1.132) |

| 460 | SPINAL FUSION EXCEPT CERVICAL W/O MCC | 22,662 | 14 | 1.311 (1.299, 1.324) |

| 470 | MAJOR JOINT REPLACEMENT OR REATTACHMENT OF LOWER EXTREMITY W/O MCC | 85,579 | 5 | 1.196 (1.194, 1.197) |

| 472 | CERVICAL SPINAL FUSION W CC | 6383 | 74 | 1.483 (1.464, 1.502) |

| 473 | CERVICAL SPINAL FUSION W/O CC/MCC | 13,828 | 32 | 1.499 (1.485, 1.513) |

| 490 | BACK & NECK PROC EXC SPINAL FUSION W CC/MCC OR DISC DEVICE/NEUROSTIM | 5237 | 89 | 1.378 (1.361, 1.395) |

| 491 | BACK & NECK PROC EXC SPINAL FUSION W/O CC/MCC | 11,567 | 37 | 1.442 (1.428, 1.456) |

| 493 | LOWER EXTREM & HUMER PROC EXCEPT HIP,FOOT,FEMUR W CC | 5334 | 88 | 1.220 (1.213, 1.228) |

| 494 | LOWER EXTREM & HUMER PROC EXCEPT HIP,FOOT,FEMUR W/O CC/MCC | 9187 | 47 | 1.215 (1.209, 1.220) |

| 552 | MEDICAL BACK PROBLEMS W/O MCC | 7562 | 65 | 1.134 (1.129, 1.138) |

| 581 | OTHER SKIN, SUBCUT TISS & BREAST PROC W/O CC/MCC | 5393 | 84 | 1.525 (1.505, 1.546) |

| 603 | CELLULITIS W/O MCC | 28,612 | 12 | 1.125 (1.124, 1.127) |

| 620 | O.R. PROCEDURES FOR OBESITY W CC | 4928 | 92 | 1.310 (1.301, 1.320) |

| 621 | O.R. PROCEDURES FOR OBESITY W/O CC/MCC | 21,179 | 15 | 1.322 (1.314, 1.329) |

| 627 | THYROID, PARATHYROID & THYROGLOSSAL PROCEDURES W/O CC/MCC | 5046 | 91 | 1.341 (1.332, 1.351) |

| 638 | DIABETES W CC | 9257 | 45 | 1.130 (1.128, 1.133) |

| 639 | DIABETES W/O CC/MCC | 8471 | 52 | 1.122 (1.120, 1.124) |

| 641 | MISC DISORDERS OF NUTRITION,METABOLISM,FLUIDS/ELECTROLYTES W/O MCC | 16,596 | 24 | 1.124 (1.122, 1.126) |

| 669 | TRANSURETHRAL PROCEDURES W CC | 4895 | 93 | 1.234 (1.226, 1.242) |

| 682 | RENAL FAILURE W MCC | 5590 | 81 | 1.147 (1.143, 1.152) |

| 683 | RENAL FAILURE W CC | 8583 | 51 | 1.140 (1.137, 1.142) |

| 690 | KIDNEY & URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS W/O MCC | 14,377 | 29 | 1.121 (1.119, 1.123) |

| 694 | URINARY STONES W/O ESW LITHOTRIPSY W/O MCC | 8339 | 55 | 1.164 (1.160, 1.168) |

| 708 | MAJOR MALE PELVIC PROCEDURES W/O CC/MCC | 7613 | 64 | 1.474 (1.462, 1.485) |

| 742 | UTERINE & ADNEXA PROC FOR NON-MALIGNANCY W CC/MCC | 12,556 | 34 | 1.292 (1.286, 1.297) |

| 743 | UTERINE & ADNEXA PROC FOR NON-MALIGNANCY W/O CC/MCC | 43,753 | 10 | 1.327 (1.324, 1.330) |

| 765 | CESAREAN SECTION W CC/MCC | 71,241 | 6 | 1.465 (1.463, 1.467) |

| 766 | CESAREAN SECTION W/O CC/MCC | 102,725 | 3 | 1.521 (1.520, 1.523) |

| 767 | VAGINAL DELIVERY W STERILIZATION &/OR D&C | 6588 | 72 | 1.598 (1.589, 1.607) |

| 774 | VAGINAL DELIVERY W COMPLICATING DIAGNOSES | 42,034 | 11 | 1.580 (1.576, 1.583) |

| 775 | VAGINAL DELIVERY W/O COMPLICATING DIAGNOSES | 271,937 | 1 | 1.644 (1.642, 1.645) |

| 776 | POSTPARTUM & POST ABORTION DIAGNOSES W/O O.R. PROCEDURE | 5388 | 85 | 1.136 (1.131, 1.141) |

| 778 | THREATENED ABORTION | 5519 | 83 | 1.099 (1.093, 1.106) |

| 781 | OTHER ANTEPARTUM DIAGNOSES W MEDICAL COMPLICATIONS | 16,031 | 25 | 1.135 (1.132, 1.139) |

| 782 | OTHER ANTEPARTUM DIAGNOSES W/O MEDICAL COMPLICATIONS | 4852 | 94 | 1.280 (1.269, 1.291) |

| 790 | EXTREME IMMATURITY OR RESPIRATORY DISTRESS SYNDROME, NEONATE | 11,521 | 38 | 1.241 (1.235, 1.246) |

| 791 | PREMATURITY W MAJOR PROBLEMS | 7324 | 68 | 1.223 (1.217, 1.229) |

| 792 | PREMATURITY W/O MAJOR PROBLEMS | 11,766 | 36 | 1.191 (1.187, 1.195) |

| 793 | FULL TERM NEONATE W MAJOR PROBLEMS | 26,979 | 13 | 1.288 (1.283, 1.292) |

| 794 | NEONATE W OTHER SIGNIFICANT PROBLEMS | 58,504 | 7 | 1.236 (1.233, 1.238) |

| 795 | NORMAL NEWBORN | 155,892 | 2 | 1.214 (1.213, 1.215) |

| 809 | MAJOR HEMATOL/IMMUN DIAG EXC SICKLE CELL CRISIS & COAGUL W CC | 4835 | 95 | 1.090 (1.088, 1.092) |

| 812 | RED BLOOD CELL DISORDERS W/O MCC | 10,784 | 41 | 1.132 (1.130, 1.135) |

| 847 | CHEMOTHERAPY W/O ACUTE LEUKEMIA AS SECONDARY DIAGNOSIS W CC | 11,128 | 39 | 1.066 (1.065, 1.068) |

| 853 | INFECTIOUS & PARASITIC DISEASES W O.R. PROCEDURE W MCC | 5377 | 86 | 1.159 (1.154, 1.165) |

| 864 | FEVER | 5375 | 87 | 1.125 (1.122, 1.129) |

| 871 | SEPTICEMIA OR SEVERE SEPSIS W/O MV 96+ HOURS W MCC | 18,402 | 16 | 1.130 (1.128, 1.132) |

| 872 | SEPTICEMIA OR SEVERE SEPSIS W/O MV 96+ HOURS W/O MCC | 11,064 | 40 | 1.116 (1.114, 1.118) |

| 881 | DEPRESSIVE NEUROSES | 12,682 | 33 | 1.135 (1.133, 1.138) |

| 885 | PSYCHOSES | 100,491 | 4 | 1.129 (1.129, 1.130) |

| 897 | ALCOHOL/DRUG ABUSE OR DEPENDENCE W/O REHABILITATION THERAPY W/O MCC | 51,095 | 9 | 1.084 (1.083, 1.085) |

| 917 | POISONING & TOXIC EFFECTS OF DRUGS W MCC | 5178 | 90 | 1.135 (1.131, 1.139) |

| 918 | POISONING & TOXIC EFFECTS OF DRUGS W/O MCC | 9536 | 42 | 1.132 (1.129, 1.135) |

| 945 | REHABILITATION W CC/MCC | 17,930 | 21 | 1.115 (1.113, 1.117) |

Estimates based on data from Truven Health MarketScan data, 2012, Inpatient Admissions files.

Data are average predicted values from ordinary least squares multivariable linear regression models with robust SEs (StataCorp, 2013), adjusted for all selected patient and health service characteristics demonstrated in Table 1.

MDC and DRG descriptions from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.25 Historic descriptions from https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareFeeforSvcPartsAB/MEDPAR.html.

Professional fee ratio estimates for other years, clinical classifications, and Medicaid patients reported in SDC Table 3, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B4.

CI indicates confidence interval; DRG, Diagnostic Related Group; MDC, Major Diagnostic Category; PFR, professional fee ratio.

DISCUSSION

In this study we quantified the amount by which facility-only financial data reported in hospital discharge datasets can underestimate the full cost of medical care patients receive during hospital admissions and ED visits by excluding professional fees. This study appears to be the first to comprehensively quantify professional fees in relation to facility fees for admissions and ED visits by year and clinical diagnosis. Financial information in MarketScan facilitated annual, diagnosis-specific PFR estimates, adjusted for multiple patient and service factors. Estimates by clinical classification reported in the SDC files were designed to be directly and easily applied to hospital discharge datasets for cost analysis.

This study had a number of limitations. Investigation into why PFR changed significantly over the study period or why differences exist between commercially insured and Medicaid PFR are beyond the scope of this study. Differences in the direction and significance of control variables’ estimated coefficients in the annual regression models suggest variation in PFR based on issues we have not observed for this analysis. Such issues could conceivably span clinical trends, changes in patients’ care-seeking behavior, policy changes that explicitly or inadvertently incentivized clinicians’ diagnostic coding practices, or macroeconomic issues. MarketScan data are not nationally representative and the MarketScan Medicaid sample includes a limited number of states. US state and region are crude indicators of geographic differences in health care costs; we lacked consistent data to further control for geographic variation, such as urban/rural location. The study did not include admissions and ED visits covered by Medicare; the highest patient age among commercially insured admissions was 64 years. A future study could apply the methods described here to estimate PFR using Medicare claims data, which is available through separate MarketScan datasets for patients with employer-based supplemental insurance.

Some of the observed PFR per visit included in our analysis dataset were high (eg, as much as 137 for 2012 commercially insured admissions, indicating that professional fees were 137 times facility fees for the admission). That was despite excluding records with the lowest 1% of facility payments per inpatient day and facility payments per ED visit, based on the assumption that those payments represented transactions between hospitals and insurance providers based on random, anomalous, and proprietary factors that we could not track through the data source. With this exclusion criteria, the right-skewness of the PFR data shrunk substantially, providing a more even distribution at all levels. Observations remaining with relatively high PFR were plausible; for example, among admissions with PFR > 100 in 2012 all involved surgery with complications to multiple parts of the body (ie, specialist clinicians with high professional fees) with relatively limited hospital stays (ie, low facility costs).

MDC, DRG, and CCS clinical classifications are designed to be comprehensive descriptions of patients’ health care needs during a particular admission or visit—and in the case of DRG, may be the basis of insurance companies’ payments—whereas primary ICD-9-CM diagnoses provide a more limited clinical and financial explanation. For example, the designation of patients’ primary diagnosis on hospital discharge records may be based on nonclinical decisions, including insurance reimbursement.21 Researchers should apply PFR estimates by ICD-9-CM diagnosis with caution (see SDC file, “How to use professional fee ratio estimates with hospital discharge data,” Supplemental Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B6). This study controlled for several patient and insurance characteristics, including health plan type, which controlled for patients with managed care insurance. However, this study could not control for provider characteristics, such as physician specialty, and hospital facility characteristics, such as ownership, organization, and geographic location, which influence health care costs.8,27–30 Hospitals’ costs vary widely by service type; for example, maternity services—a frequent cause for inpatient admission—are outliers.31 PFR estimates by individual clinical classifications (reported in SDC Table 3, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B4 and SDC Table 4, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B5) are likely more relevant for health services research than overall annual PFR (reported in Table 3).

We selected a presentation of results we anticipated would be most relevant to cost analyses using hospital discharge data—that is, predicted PFR stratified by year and multiple clinical classifications. This aim limited our modeling options. The PFR distribution has a right tail, similar to distributions common among health care expenditure variables. Ordinary least squares models using transformed expenditure estimates—for example, log or other transformations with variations such as the addition of a smearing retransformation factor—as dependent variables may produce more precise and robust estimates than direct analysis of untransformed expenditure variables.32 However, retransformation to the original scale (required to fulfill our aim of reporting adjusted mean PFR for direct application to hospital discharge data) would have undermined the potential advantages of such an approach. One relic of this modeling approach is that the lower 95% CI of predicted PFR for a few clinical diagnoses was less than zero, and should not be regarded as credible. Generalized linear models are commonly used to model expenditure data,33 although it was not feasible to use such models with our computing resources given the very large sample sizes (ie, 2.6 million admissions among commercially insured patients in 2012), the number of models estimated, and the presentation of results selected for direct application of PFR estimates to hospital discharge data. This study represents a first attempt at creating comprehensive data source for PFR estimates; future studies can improve upon the methods proposed here.

This study estimated PFR per admission and ED visit based on payments that hospitals and physicians received for medical services, whereas hospital charges reported in hospital discharge data multiplied by CCR provide an estimate of hospitals’ costs to provide services. Both approaches yield recognized estimates of medical costs, but this means that our PFR estimates are not precisely complementary to facility cost estimates from hospital discharge data. This issue might be mitigated by recent research suggesting CCR can be a reasonable proxy for price (or payments)-to-charge ratios, which are more directly analogous to our PFR estimates.8 Despite what might be modest differences in the nature of financial data underlying our PFR estimates versus that underlying hospital discharge data, we propose that our approach offers a reasonable option for improving cost estimates from hospital discharge data by accounting for professional fees.

Excluding professional fees underestimates health care costs. Despite limitations, the PFR estimates generated in this study may offer an opportunity to address the systematic and substantial underestimation of health care service costs using facility-only costs reported in hospital discharge data. Adjustment for professional fees in some manner is recommended when hospital facility-only financial data are used to estimate health care costs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Herbert Wong and Zeynal Karaca at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for their comments.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Website, http://www.lww-medicalcare.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Love D, Rudolph B, Shah GH. Lessons learned in using hospital discharge data for state and national public health surveillance: implications for Centers for Disease Control and prevention tracking program. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14:533–542. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000338365.66704.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Overview of HCUP. [Accessed January 22, 2014];2011 Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/data/hcup/index.html.

- 3.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. HCUP comorbidity software (version 3.7) [Accessed March 4, 2014];2013 Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/pubsearch/pubsearch.jsp.

- 4.Schoenman J, Sutton J, Kintala S, et al. The Value of Hospital Discharge Databases. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoenman JA, Sutton JP, Elixhauser A, et al. Understanding and enhancing the value of hospital discharge data. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64:449–468. doi: 10.1177/1077558707301963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Association of Health Data Organizations. About state health care data reporting systems. [Accessed January 23, 2014];2014 Available at: https://www.nahdo.org/data_resources. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Overview of the nationwide inpatient sample. [Accessed July 15, 2013];2013 Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp.

- 8.Levit KR, Friedman B, Wong HS. Estimating inpatient hospital prices from state administrative data and hospital financial reports. Health Serv Res. 2013;48:1779–1797. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehrotra A, Hussey P. Including physicians in bundled hospital care payments: time to revisit an old idea? JAMA. 2015;313:1907–1908. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare claims processing manual, rev. 2876. [Accessed April 8, 2014];2014 Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Internet-Only-Manuals-IOMs-Items/CMS018912.html.

- 11.Mason RJ, Moroney JR, Berne TV. The cost of obesity for nonbariatric inpatient operative procedures in the United States: national cost estimates obese versus nonobese patients. Ann Surg. 2013;258:541–551. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a500ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasegawa K, Tsugawa Y, Brown DF, et al. Trends in bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the United States, 2000–2009. Pediatrics. 2013;132:28–36. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1033–1046. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finklestein EA, Corso PS. The Incidence and Economic Burden of Injuries in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. Associates MTa. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogowski J. Cost-effectiveness of care for very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 1998;102:35–43. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Truven Health Analytics. Truven Health Analytics MarketScans databases. [Accessed January 28, 2014];2014 Available at: http://www.truvenhealth.com/your_healthcare_focus/pharmaceutical_and_medical_device/data_databases_and_online_tools.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Truven Health Analytics. Truven Health MarketScan® Research Databases (Data Year 2012 Edition) Ann Arbor, MI: Truven Health Analytics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Bureau of Economic Analysis. Table 2.5.4: price indexes for personal consumption expenditures by function (line 37: health) [Accessed August 12, 2014];2014 Available at: http://bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?ReqID=9&step=1#reqid=9&step=1&isuri=1.

- 19.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. FY2014 clinical classifications software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. [Accessed April 7, 2014];2014 Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp.

- 20.National Center for Health Statistics (US) Health, United States, 2013: With Special Feature on Prescription Drugs. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics (US); 2014. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209224/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niederkrotenthaler T, Xu L, Parks SE, et al. Descriptive factors of abusive head trauma in young children–United States, 2000–2009. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37:446–455. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.North Carolina Industrial Commission, Medical Fees Section. CPT codes and fees: 2014 CPT codes. [Accessed March 23, 2015];2014 Available at: http://www.ic.nc.gov/ncic/pages/commcode.htm.

- 24.Social Science Computing Cooperative. Exploring regression results using margins. [Accessed April 3, 2014];2014 Available at: http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/sscc/pubs/stata_margins.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Details for title: FY 2013 final rule tables (table 5) [Accessed January 28, 2014];2013 Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY-2013-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY2013-Final-Rule-Tables.html.

- 26.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Version 31 full and abbreviated code titles—effective October 1, 2013. [Accessed January 28, 2014];2013 Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD9ProviderDiagnosticCodes/codes.html.

- 27.Chirikov VV, Stuart B, Zuckerman IH, et al. Physician specialty cost differences of treating nonmelanoma skin cancer. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;74:93–99. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31828d73f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chukmaitov A, Harless DW, Bazzoli GJ, et al. Delivery system characteristics and their association with quality and costs of care: Implications for accountable care organizations. Health Care Manage Rev. 2014;40:92–103. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newton AN, Ewer SR. Inpatient cancer treatment: an analysis of financial and nonfinancial performance measures by hospital-ownership type. J Health Care Finance. 2010;37:56–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Kessler DP. Vertical integration: hospital ownership of physician practices is associated with higher prices and spending. Health Aff (Project Hope) 2014;33:756–763. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salemi JL, Comins MM, Chandler K, et al. A practical approach for calculating reliable cost estimates from observational data: application to cost analyses in maternal and child health. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11:343–357. doi: 10.1007/s40258-013-0040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manning WG, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? J Health Econ. 2001;20:461–494. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manning WG, Basu A, Mullahy J. Generalized modeling approaches to risk adjustment of skewed outcomes data. J Health Econ. 2005;24:465–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.