Abstract

Prognostic factors in pilocytic astrocytomas (PA) and pilomyxoid astrocytomas (PMA) include extent of resection, location and age but no molecular markers have been established. Insulin-like growth factor-II messenger RNA binding protein-3 (IMP3, IGF2BP3) is predictive of an unfavorable prognosis in other tumors including high grade astrocytomas but its role in PA/PMA is unknown. This study aimed to determine the expression and prognostic value of IMP3 in pediatric PA/PMAs. IMP3 protein expression was examined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in 77 pediatric PAs (n=70) and PMAs (n=7) and scored on a subjective scale. Strong diffuse staining for IMP3 was observed in 31% (24/77) of tumors and associated with a shorter progression free survival (HR=2.63; p=0.008). This cohort confirmed previously identified prognostic factors including extent of resection, age and tumor location. Currently, only clinical factors are weighed to stratify risk for patients and to identify those who should receive further therapy. Multivariate analyses identified IMP3 expression as an independent prognostic factor (HR=2.45; p=0.016) when combined with high/low risk stratification. High IMP3 as measured by IHC has potential utility as an additional predictor of poor prognosis in pediatric PA/PMAs and warrants evaluation in larger cohorts.

Keywords: IMP3, IGF2BP3, pilomyxoid astrocytoma, pilocytic astrocytoma, prognosis

Introduction

Pilocytic astrocytomas (PA, WHO grade I) are most commonly encountered in children and young adults in cerebellum, hypothalamus, optic chiasm and thalamic locations. Pilomyxoid astrocytomas (PMA, WHO grade II) occur in children less than 2 years of age, often affect hypothalamic/suprasellar regions and may present with leptomeningial dissemination. PAs in several anatomical locations are amenable to surgical resection and good control, although both PAs and PMAs in hypothalamus and suprasellar regions usually cannot be treated by surgery alone. An unfavorable anatomical location contributes, at least in part, to a significant number of children (> 33%) who will eventually suffer from tumor progression (1). Although neither PA nor PMA is likely to transform to a higher grade tumor (2), repeated recurrences and the necessity for multiple surgeries may result in devastating neurological damage.

Clinical prognostic markers including extent of surgical resection, tumor location and age significantly impact overall and event-free survival and may help delineate patients who require adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation rather than surgical resection alone (3–5). Currently, no immunohistochemical or molecular marker can be utilized to predict the recurrence risk of these tumors. Studies evaluating the prognostic value of cell cycle markers such as Ki-67 and cyclin D1 have shown conflicting results regarding the influence of mitotic rate on recurrence risk (6–9). Tibbetts et al. showed that histological features of vascular hyalinization, calcification, oligodendroglioma-like features and necrosis had statistically significant associations with poor patient outcome (7). Rodriguez et al. identified aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member L1 (ALDH1L1) as an underexpressed candidate biomarker in aggressive subtypes of PA (9). Additional prognostic biomarkers would be of great utility in determining which patients require more aggressive therapy.

One candidate biomarker is insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 3 (IMP3, IGF2BP3). IMP3 is a member of a family of IGF2 mRNA binding proteins that include IMP1 (IGF2BP1) and IMP2 (IGF2BP2) (10–12). Located on chromosome 7p11.5, IMP3 is involved in the early stages of embryonic growth and development (10, 25). It is thought to act via regulation of IGF2 mRNA localization, transport, translation and turnover. IMP3 has been implicated in the functions of cellular adhesion and invasion (26). As an oncofetal protein, IMP3 is expressed at low or undetectable levels in normal adult tissues (12).

IMP3 is predictive of an unfavorable prognosis in a variety of non-CNS tumors (13–22). Increased IMP3 expression predicts progression and poor outcome in non-small cell lung cancer, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, clear cell ovarian cancer, renal cell carcinoma, colon cancers, bile duct carcinoma and others (13–22). IMP3 is overexpressed in the highly-aggressive, triple negative breast cancer and was found to be repressed by estrogen receptor β (ERβ) and activated by epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling (22). Little is known about IMP3 expression in brain tumors. A study by Savasini et al. reported that IMP3 mRNA and protein expression is up-regulated in adult glioblastoma compared to lower grade astrocytomas and positive IMP3 staining confers a poor prognosis in glioblastoma (23). The study also provided evidence that IMP3 promotes proliferation, anchorage-independent growth, angiogenesis and invasion and translationally activates IGF2 and the downstream phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways. Another study by Serão et al. identified IMP3 as a prognostic marker in glioblastoma (24).

The present study evaluated the expression and prognostic value of IMP3 in a large, pediatric cohort of PAs and PMAs. Confounding prognostic variables including age, tumor location and extent of surgical resection were evaluated to help define a relationship between known factors contributing to poor outcomes and IMP3 expression.

Materials and Methods

Patient Cohort

A retrospective analysis was performed on tumor specimens obtained at presentation from Children's Hospital Colorado between 1995 and 2009. All studies were conducted in compliance with local and federal research protection guidelines and institutional review board regulations (COMIRB #95-500 and #08-0944). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) specimens included 70 PA and 7 PMA according to WHO tumor classification guidelines. Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type-I and those with anaplastic PA, an aggressive WHO grade III variant of PA, were excluded from this analysis (27).

Immunohistochemistry

IHC was performed on formalin fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissue sections. Slides were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and cut at 5 microns. Based on hematoxylin and eosin stained sections, optimal sections containing tumor were selected for IMP3 immunostaining; in general, slides with smaller tissue volumes were selected for staining to avoid irregular distribution of reagents on large tissue sections. All sections were immunostained in batch fashion. Slides were deparaffinized and antigen retrieval was performed using LPH and HPH Buffer (BioCare Medical, Concord, CA) for 20 minutes at 99°C followed by a 20 minute cool down. Subsequent steps were performed using the Bond Polymer Refine HRP/DAB Detection Kit (Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL) on a Bond autostainer according to the standard protocol. Incubation with primary antibody at a 1:100 dilution (mouse monoclonal anti-IMP3, code M3626; Dako) (Dako, Carpineteria, CA) was performed for one hour. All sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Immunostaining was scored by the neuropathologist (BKD), who was blinded to specific case numbers and previously rendered diagnoses. All scoring was conducted twice over a several month interval for concordance. After reviewing the slides in blinded fashion, the code was broken and slides were re-grouped according to histological diagnosis for the final review. The overall impression was the same as the original review, but this allowed direct comparisons between cases with similar diagnoses. For IMP3, a subjective scoring scale was utilized, with zero to very rare individual immunoreactive cells yielding a score of 0, scattered individual immunoreactive tumor cells giving a score of 1+, and diffuse immunostaining of tumor cells in optimally fixed and stained areas yielding a score of 2+. Non-specific immunostaining of the granular cell layer of cerebellum was easily distinguished from true immunoreactivity within the tumor.

Gene Expression Microarray Analysis

Comprehensive gene expression of 17 PA and 7 PMA was analyzed using Affymetrix GeneChip microarrays. Samples were collected at the time of surgery and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA was extracted from each sample using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA quality was measured using a 2100 BioAnalyser (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). RNA was processed as described previously (28) and hybridized to HG-U133 Plus 2.0 GeneChips (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Microarray data from the samples was background-corrected and normalized using the gcRMA algorithm. One probe set per gene, based on highest overall expression level across samples, was selected for use in subsequent analyses.

Gene Ontology Analysis

The computer-based gene ontology tool DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery, http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov) was used to assess gene lists for enrichment of genes annotated with specific Gene Ontology Project terms (GOTERM, www.geneontology.org) (29). Enrichment is defined as more genes than would be expected by chance that are associated with a specific phenotype or variable.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical calculations were analyzed with R (http://cran.r-project.org) and Prism statistical analysis program (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). For all tests, a level of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Differences between survival curves were analyzed for significance using the log-rank test. Multivariate analysis of the relative importance of factors to survival was performed using the Cox proportional hazards method.

Results

Patient Demographics

The median age of PA diagnosis was 8 years (age range: 0 months – 17 years). The median age of PMA diagnosis was 6 months (age range: 4 months – 28 months). The male to female ratio of the cohort as a whole was 1.0:1.0 with no differences when broken down by PA versus PMA. Thirty-four percent of tumors were cerebellar (26/77), 21% were suprasellar (16/77) and 30% were located in the supratentorial midline (18/77). Gross total resection was noted in 43% of patients (33/77). Forty-two percent of patients were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy at diagnosis (32/77). One patient received radiation at diagnosis.

In keeping with prior studies, progression rates were determined with respect to location and extent of surgery (Table 1). In this cohort, 61% of children were progression-free (follow-up mean 8.8 yrs, range 3.0–17.8 yrs). This finding is consistent with published data from other large cohorts reporting a range of progression-free survival from 33–89% (1, 4, 5). Gross total resection was achieved in 81% (21/26) of cerebellar tumors and was associated with low incidence (5%, 1/21) of progression. However, if only partial resection was achieved for cerebellar tumors, the rate of progression was increased (80%, 4/5).

TABLE 1.

Recurrence rate with respect to location and extent of resection in pediatric pilocytic astrocytoma and pilomyxoid astrocytoma

| Extent of Resection | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross Total | Partial | Biopsy | Total | ||

| Location | Cerebellum | 5% (1/21) | 80% (4/5) | none | 19% (5/26) |

| Other | 42% (5/12) | 41% (9/22) | 65% (11/17) | 49% (25/51) | |

| Total | 18% (6/33) | 48% (13/27) | 65% (11/17) | 39 % (30/77) | |

IMP3 Expression in Pediatric Pilocytic and Pilomyxoid Astrocytoma

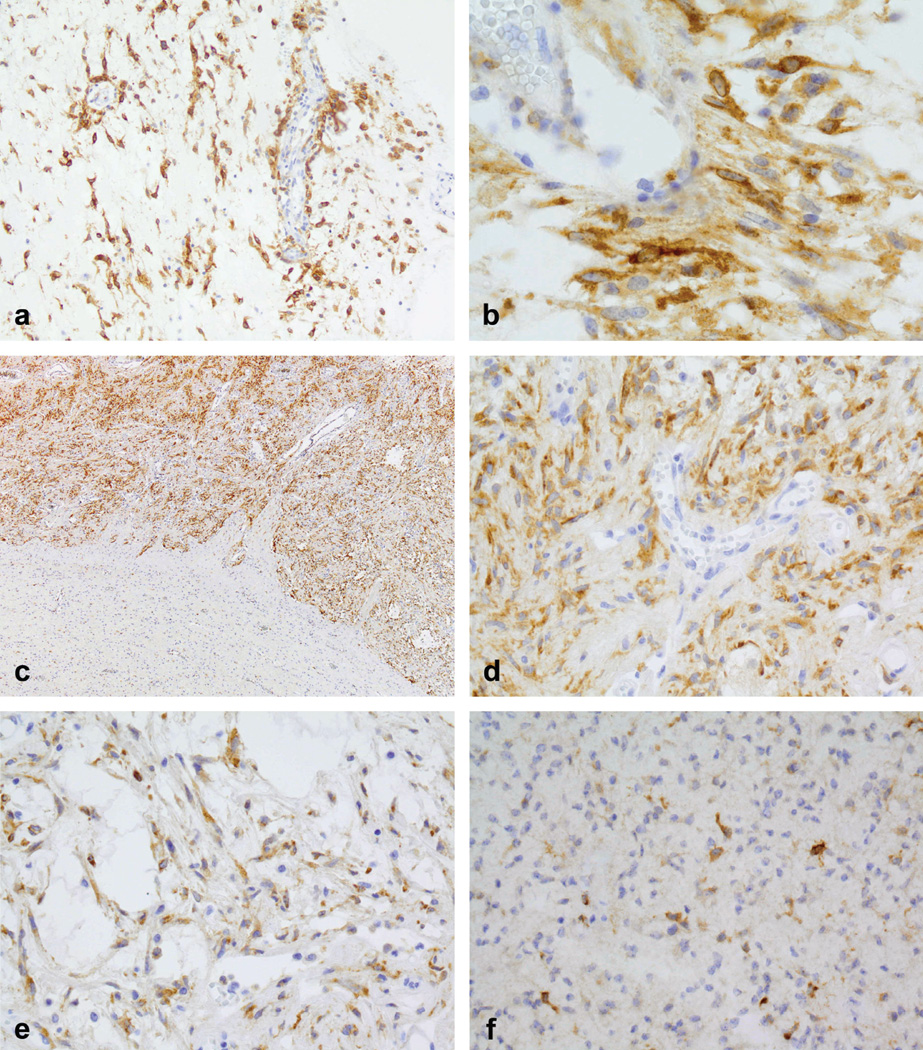

Immunohistochemical staining for IMP3 was performed on 77 pediatric tumors (7 PMAs and 70 PAs). Diffuse, strong staining for IMP3 (score 2+) was observed in 31% (24/77) of tumors. Figure 1 displays examples of IMP3 staining patterns. Strong, diffuse 2+ immunostaining is illustrated in both pilomyxoid (Figures 1A, 1B) and pilocytic (Figures 1C, 1D, 1E) astrocytoma examples, with 1+ immunoreactivity shown in Figure 1F. All immunostaining for IMP3 was diffusely cytoplasmic (Figure 1B); no membranous or nuclear staining was encountered. In cases of PA where a biphasic pattern was present, both components showed immunoreactivity (Figures 1C, D, E), although often both compact and loose microcystic areas were not always represented on the single tissue section used for staining. Immunoreactivity was not seen in blood vessels or erythrocytes (Figure 1B) or normal brain tissue (bottom area of image, representing superficial cerebellar cortex, Figure 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Representative examples of IMP3 staining patterns in pilocytic astrocytoma (PA) and pilomyxoid astrocytoma (PMA). (A) IMP3 expression when diffuse and strong (i.e., 2+) appeared to be present in more than 75% of the tumor in that section (PMA)(400× magnification). (B) All immunostaining for IMP3 was diffusely cytoplasmic; no membranous or nuclear staining was encountered (PMA) (800×). IMP3 expression was not seen in blood vessels or erythrocytes (B) or normal brain tissue (C) (bottom area of image, representing superficial cerebellar cortex). In PAs that typically have a biphasic appearance, IMP3 expression was seen in both the compact areas(C, D) (100× and 400× respectively), and (E) the loose microcystic areas (400×). (F) Low IMP3 expression (1+) in a PA (400×).

Examples of PAs with immunostaining at all three scoring levels could be identified. Seventeen of the 70 PAs exhibited no IMP3 expression, 34 showed low expression of IMP3 (1+) and 19 exhibited strong expression of IMP3 (2+). Of the 7 PMAs analyzed, no PMAs were negative for IMP3 protein expression. Two PMA exhibited focal staining of individual cells (1+) and the remaining five PMAs exhibited strong staining (2+) for IMP3. Strong (2+) staining for IMP3 was observed in 23% (6/26) of cerebellar and 35% (18/51) of non-cerebellar tumors.

A comparison of IMP3 mRNA expression in 17 PA and 7 PMA using gene expression microarray analysis also revealed that IMP3 mRNA expression was 12-fold higher in PMA compared to PA (p=0.007). Both IHC and gene expression microarray data were available for 20 tumor specimens. Protein and mRNA expression were found to have a significant, positive correlation (p=0.016, Pearson's R=0.529).

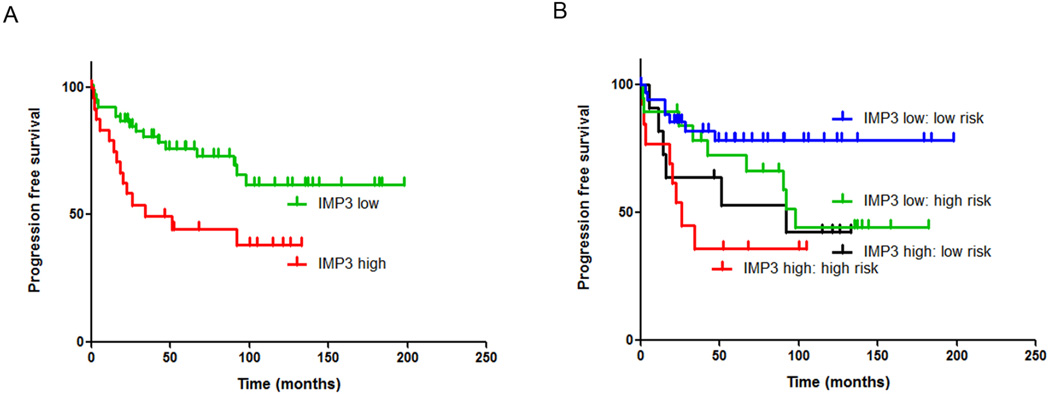

IMP3 Expression is a Prognostic Factor for Tumor Progression

In the entire cohort (n=77), a high IMP3 protein expression score (2+) was associated with a shorter progression free survival (PFS) (HR= 2.63; p=0.008) (Table 2; Figure 2A). IMP3 protein expression, as measured by IHC, was significantly higher in progressive than non-progressive PMA and PAs (student's t-test, p=0.0187). No prognostic correlation (log rank, p = 0.22) was observed for IMP3 mRNA expression in the smaller cohort of tumor samples for which gene expression microarray data was available (n=24), possibly due to insufficient sample numbers.

TABLE 2.

Univariate progression free survival analyses of IMP3 and clinical factors in a cohort of pediatric pilocytic astrocytoma and pilomyxoid astrocytoma (n=77)

| Variable | Percent of total |

HR | Lower 95% CI |

Upper 95% CI |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMP3 high (=2+) | 31% (24/77) | 2.63 | 1.28 | 5.41 | 0.008 |

| Gross total resection | 42% (33/77) | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.57 | 0.002 |

| Resected (gross total + partial) | 78% (60/77) | 0.37 | 0.18 | 0.79 | 0.010 |

| Cerebellar location | 34% (26/77) | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.84 | 0.021 |

| Age < 3 years | 19% (15/77) | 2.63 | 1.18 | 5.88 | 0.018 |

| Diagnosis (PMA) | 9% (7/77) | 2.92 | 0.69 | 12.34 | 0.144 |

| Gender (male) | 51% (39/77) | 0.71 | 0.34 | 1.46 | 0.35 |

| High risk stratification | 42% (32/77) | 1.90 | 0.92 | 3.91 | 0.083 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PMA, pilomyxoid astrocytoma

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier progression-free survival analysis of IMP3 as a single variable, and in combination with high/low risk stratification. (A) High IMP3 (2+) protein expression, was significantly associated with shorter progression free survival. (B) High IMP3 was an independently prognostic variable when combined with high/low risk stratification based on clinical prognostic factors.

Univariate analyses of other clinical features confirmed that the known risk factors of extent of surgery, age and tumor location were also prognostic for progression in the present cohort (Table 2). Gross total resection (GTR) (42%, 33/77) demonstrated the strongest association with PFS, having a significant benefit to patient outcome (HR 0.23; p=0.002). Resection (gross total or subtotal) versus biopsy alone was also strongly associated with longer PFS (HR 0.37; p=0.010). Age less than 3 years (19%, 15/77) conveyed a significantly worse outcome (HR 2.68; p=0.018). Cerebellar location (34%, 26/77) conveyed a longer progression free survival (HR 0.32; p=0.021) when compared to other non-cerebellar locations. Consistent with other studies, gender was not significantly correlated with tumor progression. Diagnosis of PMA was not significantly associated with outcome, although this is likely due to the relatively small number included in this study (7/77).

Patients in this cohort were stratified into low/high risk based on the established prognostic factors identified above by the clinical neuro-oncology team. Factors considered included extent of resection, histologic diagnosis, tumor location and age. These high-risk patients received adjuvant therapy. In the present cohort, 42% (32/77) of patients were additionally treated with chemotherapy following surgery. Patients considered low risk received no adjuvant chemotherapy and were instead subject to routine follow-up. Seventeen of 32 (53%) patients treated with chemotherapy progressed. Among those not receiving chemotherapy, i.e. stratified into the low risk category, 13 of 45 (29%) also progressed. Univariate analysis showed patients treated with chemotherapy had a worse outcome than those who were not (HR = 1.90) but this was not statistically significant (p=0.083) (Table 2). This is in keeping with the adverse clinical features initially identified.

Multivariate analysis was utilized to assess whether IMP3 was an independent prognostic factor compared to other established prognostic clinical factors. Using those clinical variables identified as prognostic for progression by univariate analysis in this cohort (Table 2), all pair-wise combinations as models for multivariate analysis were performed (Table 3). By this analysis, the most prognostic model of paired variables was GTR and age < 3 years (log-rank, p=0.00023), both well established clinical factors in PA and PMA. GTR and IMP3 was the second strongest prognostic pair (log rank, p=0.0037) although IMP3 only approached significance in this model (p=0.069). IMP3 was independently prognostic in multivariate analyses when modeled pair-wise with resection, cerebellar location and age (p=0.022, p=0.19 and p= 0.032 respectively). When IMP3 and age were combined, IMP3 retained significance whereas age lost significance.

TABLE 3.

Pairwise multivariate progression free survival analyses of IMP3 and clinical factors in a cohort of pediatric pilocytic astrocytoma and pilomyxoid astrocytma (n=77) ranked according to lowest log-rank p-value for each model.*

| Model | Variable | Hazard ratio |

Lower 95th percentile |

Upper 95th percentile |

p-value | Log rank p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTR and age < 3 yrs | 0.00023 | |||||

| GTR | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.61 | 0.0023 | ||

| Age | 2.33 | 1.04 | 5.00 | 0.039 | ||

| GTR and IMP3 high (2+) | 0.0037 | |||||

| GTR | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.68 | 0.0054 | ||

| IMP3 | 1.98 | 0.95 | 4.14 | 0.069 | ||

| IMP3 high (2+) and resected | 0.0015 | |||||

| IMP3 | 2.35 | 1.13 | 4.88 | 0.022 | ||

| resected | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.91 | 0.029 | ||

| GTR and cerebellar location | 0.0023 | |||||

| GTR | 0.28 | 0.10 | 0.83 | 0.021 | ||

| cerebellar | 0.69 | 0.22 | 2.18 | 0.530 | ||

| IMP3 high (2+) and cerebellar location | 0.0023 | |||||

| IMP3 | 2.38 | 1.16 | 4.92 | 0.019 | ||

| cerebellar | 0.35 | 0.13 | 0.93 | 0.035 | ||

| GTR and high risk stratification | 0.0024 | |||||

| GTR | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.59 | 0.0028 | ||

| High risk | 0.84 | 0.37 | 1.92 | 0.680 | ||

| Age < 3 yrs and resected | 0.0042 | |||||

| age | 2.08 | 0.92 | 4.76 | 0.078 | ||

| resected | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.97 | 0.041 | ||

| Age < 3 yrs and cerebellar location | 0.0082 | |||||

| age | 2.22 | 0.99 | 5.00 | 0.052 | ||

| cerebellar | 0.36 | 0.14 | 0.95 | 0.039 | ||

| IMP3 high (2+) and high risk stratification | 0.0084 | |||||

| IMP3 | 2.45 | 1.18 | 5.07 | 0.016 | ||

| high risk | 1.70 | 0.82 | 3.52 | 0.155 | ||

| IMP3 high (2+) and age < 3 yrs | 0.0095 | |||||

| IMP3 | 2.27 | 1.07 | 4.79 | 0.032 | ||

| age | 2.08 | 0.91 | 4.69 | 0.082 | ||

Models in which neither variable was independently significant are excluded.

Abbr: GTR, gross total resection

As multiple clinical factors determine progression free survival in this cohort, multivariate analyses that combine all clinical factors into a single model is warranted. However, the present cohort is of insufficient size to accurately perform such an analysis. Despite this limitation, a comparable analysis was performed using the high/low risk stratification to determine whether patients went on to receive adjuvant chemotherapy, which in effect reduces the multiple prognostic clinical factors to a single variable. IMP3 was therefore paired with risk stratification in a multivariate analysis model. In those patients stratified into high/low risk groups, IMP3 was an independent prognostic factor by multivariate analysis (HR= 2.45, p= 0.016) (Table 3; Figure 2B). Of note, in those patients stratified into the low risk group, and thus not treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, high IMP3 expression conferred a significantly worse outcome (HR= 4.80, p=0.023). Patients in the high risk group also showed a shorter progression free survival in high versus low IMP3, although this difference did not reach significance (HR=2.28, p=0.125).

Mitosis-related genes are the predominant function of genes positively correlated with IMP3

Research on the biological function of IMP3 in PA and PMA is severely limited by the lack of a cell line model for these brain tumors. However, gene expression microarray data can be used to ascertain more information about the potential function and biological significance of IMP3. Twenty-four PA and PMA tumors were analyzed for genes with significant IMP3 mRNA expression correlation. Of the 54,775 probesets included in the analysis, 263 genes were found to significantly correlate with IMP3 mRNA expression (p<0.005, Pearson's R>0.53). These genes were then analyzed for enrichment of biological processes based on Gene Ontology (GO) terms. The top five enriched biological processes were nuclear division, mitosis, M phase of mitotic cell cycle, organelle fission, and M phase (Table 4). The association of the highest ranking gene ontologies with cell cycling provides preliminary evidence that IMP3 may be a surrogate marker of mitotic activity in PA and PMA.

TABLE 4.

Top five enriched biological processes among genes that correlate (p<0.005) with IMP3 expression in pilocytic astrocytoma and pilomyxoid astrocytoma

| Rank | Ontology | GOterm ID | p-value | Fold-enrichment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nuclear division | 280 | 7.38×10−13 | 7.73 |

| 2 | Mitosis | 7067 | 7.38×10−13 | 7.73 |

| 3 | M phase of mitotic cell cycle | 87 | 1.05×10−12 | 7.59 |

| 4 | Organelle fission | 48285 | 1.61×10−12 | 7.43 |

| 5 | M phase | 279 | 5.31×10−12 | 5.87 |

Abbr: GOterm ID, gene ontology accession number

Discussion

Despite the high incidence of pediatric PA and PMA, the biological factors that influence patient outcome remain poorly understood and there are currently no robust prognostic molecular markers to identify up-front which children will suffer from tumor progression. IMP3 is an oncofetal RNA binding protein that has recently been shown to predict a poor prognosis in a variety of non-CNS tumors in addition to adult glioblastoma (13–23). The aim of the present study was to evaluate the expression and prognostic value of IMP3 in a large cohort of pediatric PA and PMA. Pediatric PA and PMA displayed a broad range of IMP3 protein expression, with histologically similar samples exhibiting either high expression in the majority of tumor cells or absent expression. Nearly one third of tumors exhibited high IMP3 staining as measured by IHC. High IMP3 protein expression was significantly associated with progression by univariate and multivariate analysis. Correlation between progression and IMP3 mRNA expression, as measured by gene expression microarray analysis, was not observed in this cohort, however the small number of samples in this group limited the power and warrants further evaluation.

In the present cohort gross total resection was the strongest clinical prognostic factor. However, in those tumors located outside of the cerebellum, a gross total resection did not confer as favorable a prognosis as it did for tumors located within in the cerebellum, with a recurrence rate of 42% as opposed to 5% (Table 1). PAs and PMAs arising outside of the cerebellum represent tumors that are often difficult to fully resect and hence biological factors may play more of a role in predicting prognosis. A further explanation that is only now being investigated by others is that PAs in different anatomical locations may have different biological origins and little is known about how this differing origin might impact outcome. Biological support for this is the fact that PAs in cerebellum have a high rate of KIAA-BRAF fusion but not BRAF V600E mutation, whereas the reverse is true in extracerebellar PAs (30–34). Consistent with the theory of biological differences between anatomic locations, our present study showed that high IMP3 was more common in non-cerebellar tumors (35% versus 23%).

The association of IMP3 expression with a more aggressive clinical course in PA and PMA prompted further investigation into the possible role that IMP3 might be playing in the biology of these tumors. The present study utilized gene expression microarray data as an unbiased approach to identify genes that significantly correlated with IMP3 expression in PA and PMA tumors. Gene ontology analysis revealed that many genes positively correlated with IMP3 were associated with cell cycle (Table 4). The potential involvement of IMP3 with cell cycling is not surprising, given its strong prognostic utility across a large variety of cancers. This analysis provides preliminary evidence that IMP3 may be a marker of mitotic activity in these tumors. However, MIB-1/Ki-67, a common immunohistochemical marker of mitotic activity, is not consistently associated with outcome in pediatric or adult PA, despite extensive study (7, 35–37). A possible explanation for the discrepancy is that IMP3 may be better able to discriminate smaller ranges of differences in cell cycling than do Ki-67 counts. Namely, the range of mitoses in PAs often falls within a very narrow range of 1–4 per 10 high power microscopic fields (HPFs) and reader variation and sampling of different areas may not reproducibly distinguish between, for example, 2 and 4 mitoses per 10 HPFs. An alternative hypothesis can be extrapolated from a study of IMP3 in glioblastoma. Suvasini et al. showed that IMP3, via control of IGF2 levels, activates the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (38). In recent years BRAF, a key kinase in the MAPK pathway, has been identified as a driver mutation in PAs, the most common of which is an activating fusion with KIAA1549 (39). IMP3 may therefore be controlling MAPK pathway activity via its interaction with IGF2. A number of IGF receptor antibody and small molecule inhibitors are available, of which some are in early clinical trials in other pediatric brain tumors (40, 41). Further research into the biological function of IMP3 in pediatric PA and PMA may provide insight into the biology of these tumors that could be exploited therapeutically.

The present study provides preliminary evidence that IMP3 may be a prognostic molecular marker for PA and PMA. Of particular note, in those patients judged by the neuro-oncologist to have a low risk of progression based on clinical prognostic variables, high IMP3 identified a number of patients who eventually progressed. These patients represent the majority of PA, for whom standard of care consists of surgery alone and routine follow-up. A portion of these patients, who are not treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, will suffer from tumor recurrence. IMP3 IHC might benefit this group of patients by redefining them into the high risk strata that receives adjuvant therapy. The clinical utility of IMP3 protein expression in better risk stratification of patients warrants further evaluation in other large study cohorts.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank The Childhood Brain Tumor Foundation for financial support of this project. Valuable immunohistochemical assistance was received by Patsy Ruegg at IHCTech. Lisa Litzenberger provided photographic expertise in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Role Justification:

Valerie Barton: Concept design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation

Andrew Donson: Concept design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation

Diane Birks: Data analysis and design, manuscript preparation

BK Kleinschmidt-DeMasters: Scored all IHC, concept design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation

Michael H. Handler: Concept design, manuscript preparation

Nicholas K. Foreman: Concept design, manuscript preparation

Sarah Z. Rush: Concept design, data interpretation, manuscript preparation

References

- 1.Tihan T, Ersen A, Qaddoumi I, Sughayer MA, Tolunay S, Al-Hussaini M, Phillips J, Gupta N, Goldhoff P, Baneerjee A. Pathologic characteristics of pediatric intracranial pilocytic astrocytomas and their impact on outcome in 3 countries: a multi-institutional study. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2012;36:43–55. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182329480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez FJ, Scheithauer BW, Burger PC, Jenkins S, Giannini C. Anaplasia in pilocytic astrocytoma predicts aggressive behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:147–160. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181c75238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Margraf LR, Gargan L, Butt Y, Raghunathan N, Bowers DC. Proliferative and metabolic markers in incompletely excised pediatric pilocytic astrocytomas--an assessment of 3 new variables in predicting clinical outcome. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13:767–774. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gnekow AK, Falkenstein F, von Hornstein S, Zwiener I, Berkefeld S, Bison B, Warmuth-Metz M, Driever PH, Soerensen N, Kortmann RD, Pietsch T, Faldum A. Long-term follow-up of the multicenter, multidisciplinary treatment study HIT-LGG-1996 for low-grade glioma in children and adolescents of the German Speaking Society of Pediatric Oncology and Hematology. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14:1265–1284. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gajjar A, Sanford RA, Heideman R, Jenkins JJ, Walter A, Li Y, Langston JW, Muhlbauer M, Boyett JM, Kun LE. Low-grade astrocytoma: a decade of experience at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2792–2799. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.8.2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher BJ, Naumova E, Leighton CC, Naumov GN, Kerklviet N, Fortin D, Macdonald DR, Cairncross JG, Bauman GS, Stitt L. Ki-67: a prognostic factor for low-grade glioma? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:996–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tibbetts KM, Emnett RJ, Gao F, Perry A, Gutmann DH, Leonard JR. Histopathologic predictors of pilocytic astrocytoma event-free survival. Acta neuropathologica. 2009;117:657–665. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0506-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horbinski C, Hamilton RL, Lovell C, Burnham J, Pollack IF. Impact of morphology, MIB-1, p53 and MGMT on outcome in pilocytic astrocytomas. Brain pathology. 2010;20:581–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez FJ, Giannini C, Asmann YW, Sharma MK, Perry A, Tibbetts KM, Jenkins RB, Scheithauer BW, Anant S, Jenkins S, Eberhart CG, Sarkaria JN, Gutmann DH. Gene expression profiling of NF-1-associated and sporadic pilocytic astrocytoma identifies aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member L1 (ALDH1L1) as an underexpressed candidate biomarker in aggressive subtypes. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2008;67:1194–1204. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31818fbe1e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen J, Christiansen J, Lykke-Andersen J, Johnsen AH, Wewer UM, Nielsen FC. A family of insulin-like growth factor II mRNA-binding proteins represses translation in late development. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1262–1270. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Runge S, Nielsen FC, Nielsen J, Lykke-Andersen J, Wewer UM, Christiansen J. H19 RNA binds four molecules of insulin-like growth factor II mRNA-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29562–29569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001156200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nielsen FC, Nielsen J, Christiansen J. A family of IGF-II mRNA binding proteins (IMP) involved in RNA trafficking. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 2001;234:93–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobel M, Xu H, Bourne PA, Spaulding BO, Shih Ie M, Mao TL, Soslow RA, Ewanowich CA, Kalloger SE, Mehl E, Lee CH, Huntsman D, Gilks CB. IGF2BP3 (IMP3) expression is a marker of unfavorable prognosis in ovarian carcinoma of clear cell subtype. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:469–475. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li D, Yan D, Tang H, Zhou C, Fan J, Li S, Wang X, Xia J, Huang F, Qiu G, Peng Z. IMP3 is a novel prognostic marker that correlates with colon cancer progression and pathogenesis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3499–3506. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0648-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellezza G, Cavaliere A, Sidoni A. IMP3 expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1205–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann NE, Sheinin Y, Lohse CM, Parker AS, Leibovich BC, Jiang Z, Kwon ED. External validation of IMP3 expression as an independent prognostic marker for metastatic progression and death for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2008;112:1471–1479. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Z, Chu PG, Woda BA, Rock KL, Liu Q, Hsieh CC, Li C, Chen W, Duan HO, McDougal S, Wu CL. Analysis of RNA-binding protein IMP3 to predict metastasis and prognosis of renal-cell carcinoma: a retrospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:556–564. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70732-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riener MO, Fritzsche FR, Clavien PA, Pestalozzi BC, Probst-Hensch N, Jochum W, Kristiansen G. IMP3 expression in lesions of the biliary tract: a marker for high-grade dysplasia and an independent prognostic factor in bile duct carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1377–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaeffer DF, Owen DR, Lim HJ, Buczkowski AK, Chung SW, Scudamore CH, Huntsman DG, Ng SS, Owen DA. Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 3 (IGF2BP3) overexpression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma correlates with poor survival. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng W, Yi X, Fadare O, Liang SX, Martel M, Schwartz PE, Jiang Z. The oncofetal protein IMP3: a novel biomarker for endometrial serous carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:304–315. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181483ff8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oy GF, Slipicevic A, Davidson B, Solberg Faye R, Maelandsmo GM, Florenes VA. Biological effects induced by insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3) in malignant melanoma. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:350–361. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samanta S, Sharma VM, Khan A, Mercurio AM. Regulation of IMP3 by EGFR signaling and repression by ERbeta: implications for triple-negative breast cancer. Oncogene. 2012 doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suvasini R, Shruti B, Thota B, Shinde SV, Friedmann-Morvinski D, Nawaz Z, Prasanna KV, Thennarasu K, Hegde AS, Arivazhagan A, Chandramouli BA, Santosh V, Somasundaram K. Insulin growth factor-2 binding protein 3 (IGF2BP3) is a glioblastoma-specific marker that activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase (PI3K/MAPK) pathways by modulating IGF-2. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:25882–25890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.178012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serao NV, Delfino KR, Southey BR, Beever JE, Rodriguez-Zas SL. Cell cycle and aging, morphogenesis, and response to stimuli genes are individualized biomarkers of glioblastoma progression and survival. BMC Med Genomics. 2011;4:49. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mueller-Pillasch F, Lacher U, Wallrapp C, Micha A, Zimmerhackl F, Hameister H, Varga G, Friess H, Buchler M, Beger HG, Vila MR, Adler G, Gress TM. Cloning of a gene highly overexpressed in cancer coding for a novel KH-domain containing protein. Oncogene. 1997;14:2729–2733. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vikesaa J, Hansen TV, Jonson L, Borup R, Wewer UM, Christiansen J, Nielsen FC. RNA-binding IMPs promote cell adhesion and invadopodia formation. EMBO J. 2006;25:1456–1468. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez FJ, Scheithauer BW, Burger PC, Jenkins S, Giannini C. Anaplasia in pilocytic astrocytoma predicts aggressive behavior. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2010;34:147–160. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181c75238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donson AM, Erwin NS, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Madden JR, Addo-Yobo SO, Foreman NK. Unique molecular characteristics of radiation-induced glioblastoma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:740–749. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e3181257190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schindler G, Capper D, Meyer J, Janzarik W, Omran H, Herold-Mende C, Schmieder K, Wesseling P, Mawrin C, Hasselblatt M, Louis D, Korshunov A, Pfister S, Hartmann C, Paulus W, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A. Analysis of <i>BRAF</i> V600E mutation in 1,320 nervous system tumors reveals high mutation frequencies in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, ganglioglioma and extra-cerebellar pilocytic astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathologica. 2011;121:397–405. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0802-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forshew T, Tatevossian RG, Lawson AR, Ma J, Neale G, Ogunkolade BW, Jones TA, Aarum J, Dalton J, Bailey S, Chaplin T, Carter RL, Gajjar A, Broniscer A, Young BD, Ellison DW, Sheer D. Activation of the ERK/MAPK pathway: a signature genetic defect in posterior fossa pilocytic astrocytomas. J Pathol. 2009;218:172–181. doi: 10.1002/path.2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones DT, Kocialkowski S, Liu L, Pearson DM, Ichimura K, Collins VP. Oncogenic RAF1 rearrangement and a novel BRAF mutation as alternatives to KIAA1549:BRAF fusion in activating the MAPK pathway in pilocytic astrocytoma. Oncogene. 2009;28:2119–2123. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfister S, Janzarik WG, Remke M, Ernst A, Werft W, Becker N, Toedt G, Wittmann A, Kratz C, Olbrich H, Ahmadi R, Thieme B, Joos S, Radlwimmer B, Kulozik A, Pietsch T, Herold-Mende C, Gnekow A, Reifenberger G, Korshunov A, Scheurlen W, Omran H, Lichter P. BRAF gene duplication constitutes a mechanism of MAPK pathway activation in low-grade astrocytomas. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1739–1749. doi: 10.1172/JCI33656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sievert AJ, Jackson EM, Gai X, Hakonarson H, Judkins AR, Resnick AC, Sutton LN, Storm PB, Shaikh TH, Biegel JA. Duplication of 7q34 in pediatric low-grade astrocytomas detected by high-density single-nucleotide polymorphism-based genotype arrays results in a novel BRAF fusion gene. Brain Pathol. 2009;19:449–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Machen SK, Prayson RA. Cyclin D1 and MIB-1 immunohistochemistry in pilocytic astrocytomas: a study of 48 cases. Human pathology. 1998;29:1511–1516. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bowers DC, Gargan L, Kapur P, Reisch JS, Mulne AF, Shapiro KN, Elterman RD, Winick NJ, Margraf LR. Study of the MIB-1 labeling index as a predictor of tumor progression in pilocytic astrocytomas in children and adolescents. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:2968–2973. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Margraf LR, Gargan L, Butt Y, Raghunathan N, Bowers DC. Proliferative and metabolic markers in incompletely excised pediatric pilocytic astrocytomas--an assessment of 3 new variables in predicting clinical outcome. Neuro-oncology. 2011;13:767–774. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suvasini R, Shruti B, Thota B, Shinde SV, Friedmann-Morvinski D, Nawaz Z, Prasanna KV, Thennarasu K, Hegde AS, Arivazhagan A, Chandramouli BA, Santosh V, Somasundaram K. Insulin growth factor-2 binding protein 3 (IGF2BP3) is a glioblastoma-specific marker that activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase (PI3K/MAPK) pathways by modulating IGF-2. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:25882–25890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.178012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sievert AJ, Jackson EM, Gai X, Hakonarson H, Judkins AR, Resnick AC, Sutton LN, Storm PB, Shaikh TH, Biegel JA. Duplication of 7q34 in pediatric low-grade astrocytomas detected by high-density single-nucleotide polymorphism-based genotype arrays results in a novel BRAF fusion gene. Brain pathology. 2009;19:449–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bagatell R, Herzog CE, Trippett TM, Grippo JF, Cirrincione-Dall G, Fox E, Macy M, Bish J, Whitcomb P, Aikin A, Wright G, Yurasov S, Balis FM, Gore L. Pharmacokinetically guided phase 1 trial of the IGF-1 receptor antagonist RG1507 in children with recurrent or refractory solid tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:611–619. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malempati S, Weigel B, Ingle AM, Ahern CH, Carroll JM, Roberts CT, Reid JM, Schmechel S, Voss SD, Cho SY, Chen HX, Krailo MD, Adamson PC, Blaney SM. Phase I/II trial and pharmacokinetic study of cixutumumab in pediatric patients with refractory solid tumors and Ewing sarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:256–262. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.4355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]