Abstract

Background

Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV and AIDS) constitutes one of the major challenges to development worldwide. Actions taken by employers of labour against staff or applicants living with HIV have great impacts in the labour force and in the fight to mitigate the impact of the disease condition. In Nigeria, there's paucity of documented work about employers of labour's behavioural intentions when they are faced with staff/applicant living with the virus. This study explored the behavioural antecedents and intentions of employers of labour in Ibadan North Local Government Area, Oyo state, Nigeria.

Methods

The study was cross-sectional survey in design. A multistage sampling technique was used to select 400 study respondents (38 public and 362 private sectors) for interview. The instrument for data collection was a pre-tested semi–structured questionnaire. Attitude was categorised as negative (score ≤ 54) and positive (score ≥55). Data were analysed and presented using descriptive and inferential statistics.

Results

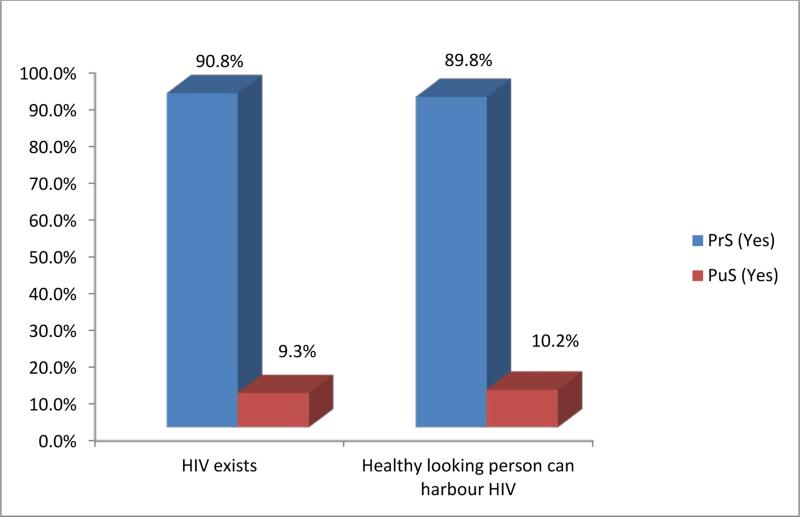

There were more males (68.2%) respondents than females (31.8%). A large majority, 79.0%, in the public sector (PuS) and 72.9% in the private sector (PrS) knew that an infected healthy looking person could harbour and transmit HIV to others. A majority, 80.0%, of which 2.3% with no formal education, 1.0% primary education, 13.5% high school education, 41.5% bachelor, 21.0% postgraduate and 0.8% with other qualifications were of the view that workers infected with HIV should not be sacked. Slightly less than half (48.0%) would keep their staff's HIV status secret while more than half, 57.0%, would not recruit a PLWHA. More PrS respondents (47.8%) claimed to have ever organised HIV/AIDS-related educational programmes for staff than PuS (42.1%) (p<0.05). Almost equal respondents (PuS 36.8%) and (PrS 36.2%) would require mandatory test for HIV before employment. Only 1.8% (PuS) and 6% (PrS) reported that their organisations had a workplace HIV and AIDS policy (p<0.05).

Conclusions

Although the respondents would tolerate staff with HIV/AIDS, their attitudinal disposition are indicative of limited knowledge about the mode of transmission and prevention of HIV including workplace policy on HIV and AIDS. Health education strategies such as training and workplace HIV/AIDS education are needed to address these shortcomings.

Keywords: Employers of labour, Employee, Applicants, HIV/AIDS Workplace-related activities, Behaviour antecedents, Behaviour intentions

Introduction

Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV and AIDS) is an important labour-related issue because of their implications for workers’ health and productivity [1, 2]; it affects the workplace in a variety of ways. Stigma and discrimination often present major challenges to the successful implementation of workplace HIV and AIDS programmes [2, 3]. Employees and job applicants living with HIV and AIDS may experience HIV-related stigma from their colleagues and most especially from their employers. The HIV and AIDS-induced stigma may result in the sack of persons living with HIV and AIDS or their being technically shown the way out of their jobs. Despite the growing body of knowledge related to HIV and AIDS, little is known about the nature of the associated stigma and workplace–based interventions geared towards addressing stigma and discrimination either as an issue in its own right or as a critical component of HIV and AIDS programme. Although most countries have come up with policy responses to the epidemic as well as plans of action, they lack specific legislation against discrimination and stigmatisation on the grounds of HIV sero-positivity. The tendency of many employers of labour has been to discriminate against employees and job applicants living with HIV and AIDS through the use of HIV testing result to exclude those that are HIV positive [2, 4]. In Nigeria, there is dearth of research–based information relating to the extent of employers of labour's perceptions and attitudes to workers living with HIV and AIDS or to applicants who are HIV positive. Although, some studies have been done by some non-governmental organisations (NGOs) which focused on workplace responses to HIV and AIDS [5], in Oyo state, there is little information relating to the knowledge, attitudes and behavioural intentions of employers of labour regarding HIV and AIDS. Yet information relating to these issues is needed for the design of appropriate workplace health education programmes geared towards making workplaces health promoting-settings especially for persons living with HIV and AIDS.

The study is useful in determining the potential effects of the level of awareness of employers of labour about HIV and AIDS, HIV and AIDS-related activities in workplace as well as factors which may likely influence their behavioural intentions towards staff or applicants living with the disease condition which have potential for influencing their health and wellbeing. In addition, awareness and behavioural intentions of employers of labour to PLWHAs is useful as baseline information for designing and implementing educational programmes for making workplaces health promoting for persons living with HIV and AIDS. Furthermore, the findings of the paper (which is a subset of larger study) will be useful in guiding the formulation of evidence-based policies geared towards promoting the health and wellbeing of PLWHAs in workplaces.

Methodology

The study was a descriptive cross–sectional survey designed to investigate the employers of labour and workplace HIV-related practices. Ibadan North Local Government Area (LGA) constitutes the study area. The LGA is one of the five LGAs in Ibadan metropolis, which is the largest city in black Africa. Ibadan is the capital city of Oyo State. Ibadan North LGA was created on 27th September 1991 out of the defunct Ibadan Municipal Government [6]; with a population of 308,119 people (male 152,608; female 155,511) [7]. Majority of the residents of Ibadan North LGA are in the private sector. They are mainly traders and artisans although some residents are civil or public servants.

The study population which consisted of all employers of labour in IBLGA;it comprises of policy makers in the public and private sector of the economy. The study population also consisted of political leaders, government bureaucrats, business owners, chairmen of companies as well as management staff in the private sector who have the power to employ, discipline and/or disengage any staff.

In order to obtain a sample of the population for the study, multi stage random sampling technique (cluster, proportionate and simple random sampling techniques) was adopted in selecting 400 employers of labour. A pre-tested semi–structured questionnaire was used for data collection. Attitude was categorised as negative (score ≤54) and positive (score ≥55). The correlation coefficient of the instrument was 0.741. This paper complied with the standard requirements of the Ethical Committee. Ethical approval was given by the Oyo State Ethical Review Committee. Informed consent was obtained from respondents.

Limitations

The fact that the present paper was a part of master of Public Health dissertation determined my selection method. To enhance representativeness of the sample, inclusion was done in such a way that the numbers were proportional to the number of employers in both private and public sectors. The selection procedure where there are many private sectors respondents, especially the short selection period, may have caused some bias and may therefore have slightly affected the external validity of the study. It is however reassuring that the findings of this study will not in any way be compromised.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

Most of the employers, 90.7%, were in the private sector and majority (68.3%) were male. A large proportion (85.5%) of the respondents was of the Yoruba speaking ethnic group. A majority (66.5%) were currently married and slightly more than half (50.8%) had bachelor or Higher National Diploma degree.

Discussion

Socio-demographic characteristics

A large majority of the study respondents were in the private sector; they constituted an important sub-group of the population that help to sustain the economy of the LGA. In most parts of the world including Nigeria, the proportion of the private sector economy is larger than the public sector hence the labour force in the private sector is always larger than the public sector [8]. Also, it is not a strange development that majority of the employers of labour were males. Gender inequity has been a perennial problem worldwide [9]. In Nigeria, few females have the capita to set up private businesses that can hire two or more employees. A large majority of the policy makers in the public sector were males too. This could be a result of the educational gap between male and female with the male being comparatively more educated than the female and so were able to secure employment in the public sector as senior officers or rise quickly to the managerial positions. However, this trend or pattern is hope to change soon as the females are increasingly becoming as educated as the males in line with the global trend on gender mainstreaming [10]. Slightly more than half of the participants were beneficiaries of higher education. Higher education is pivotal to appointment or promotion to management level to function as a policy maker especially in the public sector. Special skills in decision-making and management of resources require some tertiary education. Even business organisations now require skilful, efficient and effective hands with tertiary education especially at the managerial level.

Awareness of HIV and AIDS

Awareness about the existence and the possibilities that a healthy looking person can harbour HIV was high among respondents. This could be explained on the ground that Ibadan has witnessed a lot of HIV and AIDS public enlightenment programmes in recent years. It is to be noted that Ibadan is home to several NGOs which carry out HIV and AIDS enlightenment activities. Some of the HIV and AIDS programmes are targeted at difference populations in Ibadan in both private and public sectors. Adequate knowledge of HIV and AIDS has great potential for facilitating the prevention and control of the pandemic. On the other hand inadequate and/or faulty knowledge of the disease may militate against prevention and control efforts and promote stigmatisation and discrimination against PLWHAs. According to Green and Kreuter, knowledge is a key behavioural antecedent [11]; this is also applicable within the context of HIV and AIDS.

Intended action against staff and applicants living with HIV and AIDS

Majority of respondents across the private and public sectors exhibited both positive and negative intentions in their responses. For instance, majority of the employers in the private and public sectors were of the opinion that a staff living with HIV and AIDS should not be invited to attend a social gathering of this organisation involving other workers and visitors. This might be as a result of the unscientific beliefs, prejudices and wrong notions held about HIV and AIDS. Health education programme in workplaces should target these intentions. The virus is not transmitted through social contact; discriminatory practice could further fuel the spread of the disease condition. The negative actions could be the result of false beliefs and poor knowledge of the disease condition. In some cultures or organisations where insufficient knowledge of the disease existed, PLWHAs were restricted from touching individuals, or sharing things with family members or co-workers for fear of losing honour and social standing. There could be instances when PLWHAs will not be introduced to guests, invited to ceremonies, or even told to stay away from their home because their family and co-workers will be afraid that they could lose their honour in the community; PLWHA themselves are often worried over the damaging effects of local attitudes towards their family because of their HIV status. Appropriate workplace programmes will go a long way in tackling this unwholesome practice [12].

However, there was an instance of positive intention among the employers of labour. This relates to training of staff living with HIV and AIDS. A large majority of participating employers in both private and public sectors disagreed with the notion that a member of staff who is HIV positive should not be recommended for further training because it would amount to a waste of resources as the worker will sooner than later fall sick and die. In addition to this, more than half of employers in the private sector and an overwhelming majority in the public sector do not support the statement that a member of staff who is HIV positive should not be recommended to train other workers for fear of infecting them (i.e. the others workers.) Misconceptions exist among some employers relating to PLWHA's. The results show that there are mixtures of positive and negative intentions existing among the participating establishments. These intentions could stem out of adequate or lack of adequate information on HIV and AIDS.

Past HIV/AIDS–related prevention and treatment activities carried out by participating organisations

Generally, few employers in both private and public sectors had organized a seminar/workshop or any other educational programme on HIV and AIDS for workers. More than half of the employers in both sectors had however informed workers about sources of information about HIV and AIDS. Moreover, about half of the participating establishments in both private and public sectors had ever make educational materials that can help increase workers’ knowledge about HIV and AIDS available to them. More than half of employers in the private sector and the public sector counselled some of their workers to go for HIV test. Many organisations in both the private and public sectors do not have HIV and AIDS related activities. Only some foreign owned companies and a few Nigerian organisations have HIV and AIDS prevention and control activities integrated within reproductive health programmes [13].

HIV/AIDS policy and activities in workplaces that would be supported by the respondents

Collectively, respondents indicated their willingness to support various HIV/AIDS-related activities. This is agreement with the Nigeria Business Coalition against AIDS (NIBUCCA) goals [13]. In Nigeria, the Nigeria Business Coalition against AIDS (NIBUCCA) ensures that each of the affiliate organisations no matter how small has an HIV and AIDS control programme. However, none of the organisations surveyed was a member of NIBUCCA. NIBUCCA's activities among other things include assisting member organisations to set up workplace programmes (WPP) [13]. Rosen also observed that national governments, international agencies, and bilateral donors are looking up to the private sector across sub-Saharan Africa for leadership, resources, and action in the fight against HIV and AIDS [14]. A few companies have responded energetically, joining AIDS business councils, implementing “best practice” prevention and treatment programs, and sponsoring local AIDS-oriented NGOs. According to NIBUCAA, interventions should be implemented and sustained in each organisation and coordinated by NIBUCCA with a view to

Upgrading workers knowledge about HIV and AIDS

Formulating and implementing appropriate workplace HIV and AIDS policy

Designing and implementing workplace HIV and AIDS control programmes and

Tackling stigmatisation and discrimination in workplaces [13]

Factors that may influence the behavioural intentions of respondents towards workers and applicants who are living with HIV and AIDS

It is noteworthy to find that no socio-demographic factor was significantly related to the possibility of a healthy looking person harbouring HIV. The apparent no significance is due to the higher proportion of respondents who indicated that a healthy looking person could harbour the virus. Collectively, socio-demographic characteristics may not be strong enough to influence intention. However, in line with Green and Kreuter, individual behavioural antecedents may influence behavioural intentions [11].

Respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics and attitudinal disposition of respondents towards workers and applicants who are living with HIV and AIDS

Attitude, a concept with varied definition by various authors, is a predisposition or a tendency to respond positively or negatively towards a certain idea, object, person, or situation. Attitude influences an individual's choice of action, and responses to challenges, incentives, and rewards. Employers of labour indicated their attitudinal dispositions which may likely lead to their behavioural intentions towards staff or application found to be living with disease condition. Attitude was found to be significantly related to education, years of work experience and marital status. As mention earlier, education to a large extent is pivotal to functioning at a management level such as a policy maker especially in the public sector [1, 2]. Special skills in decision-making and management of resources require some tertiary education. Even business organisations now require skilful, efficient and effective hands with higher level of education especially at the managerial level. In addition to education, adequate knowledge of HIV and AIDS has great potential for facilitating the prevention and control of the pandemic. On the other hand inadequate and/or faulty knowledge of the disease may militate against prevention and control efforts and promote stigmatisation and discrimination against PLWHAs. Knowledge is a key behavioural antecedent [11] within the context of HIV and AIDS. The study population, employers of labour including key policy makers, should be very knowledgeable about HIV and AIDS. This will enhance their capacity to design, implement and institutionalise HIV and AIDS prevention and control programmes in workplaces in line with the [15] and [16] guidelines.

Conclusions

The findings of this study revealed the behaviours (practices), behavioural intentions and behavioural antecedents which should be addressed with appropriate HIV and AIDS education strategies in workplaces. In addition, they could be relied upon for the design of educational interventions for making workplaces health promoting environments for PLWHAs.

According to UNAIDS [17], there are three reasons why it is necessary to deal with HIV and AIDS in workplaces. Firstly, HIV and AIDS has a huge impact on the world of work because it reduces the supply of labour and available skills, increase labour costs, reduces productivity, threatens the livelihoods of workers and employers, and creates environments which undermine the rights of workers. Secondly, the workplace is an appropriate place to tackle HIV and AIDS. This is more so because there are a set of standards for working conditions and labour relations. Workplaces are communities where people come together, interact and share experiences. This provides an opportunity for awareness raising, the conduct of education programmes, and the protection of human rights. Thirdly, employers and trade union leaders are important opinion leaders in their communities and countries. Leadership is crucial to the successful fight against HIV and AIDS at all levels including the family, community and workplaces.

The findings of this study could be used as a training needs assessment for the design and development of a training curriculum for upgrading the knowledge and skills of policy makers relating to the design and implementation of workplace HIV and AIDS education programmes.

Recommendations.

The behaviour change communication interventions should focus on employers of labour's awareness and knowledge of HIV and AIDS, perceptions about workers and applicants living with HIV and AIDS, workplace HIV and AIDS prevention and treatment programmes, workplace practices towards persons living with the disease condition, HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination, development of communication materials, training of peer educators, and information on access to services and workplace HIV and AIDS policy.

Figure 1.

Respondents’ awareness of HIV and AIDS

Table 1.

Respondents' intended action against staff and applicants living with HIV and AIDS

| Attitude | Yes No (%) | No No (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Staff living with HIV and AIDS should not be invited to attend a social gathering of this organisation involving other workers and visitors | ||

| PrS | 135 (37.6) | 224 (62.4) |

| PuS | 3 (8.1) | 34 (91.9) |

| Any staff in this establishment who has HIV and AIDS cannot be asked to represent our organisation somewhere | ||

| PrS | 127 (35.4) | 232 (64.6) |

| PuS | 2 (5.4) | 35 (94.6) |

| If any staff is discovered to be HIV positive, will not recommend him/her for promotion | ||

| PrS | 142 (40.3) | 210 (59.7) |

| PuS | 4 (10.8) | 33 (89.2) |

| Cannot recommend a member of staff who is HIV positive for further training because it would amount to a waste of resources as the worker will sooner than later fall sick and die | ||

| PrS | 141 (39.5) | 216 (60.5) |

| PuS | 6 (16.2) | 31 (83.8) |

| Cannot recommend a member of staff who is HIV positive to train other workers for fear of infecting them (i.e. the others workers) | ||

| PrS | 152 (42.5) | 206 (57.5) |

| PuS | 3 (8.1) | 34 (91.9) |

| Any staff in our organization that is HIV positive cannot be given a leadership role | ||

| PrS | 143 (40.1) | 214 (59.9) |

| PuS | 3 (8.1) | 34 (91.9) |

| Workers who are found to be HIV positive would be relieved of their jobs as they would become economic burden to our organization | ||

| PrS | 141 (39.5) | 216 (60.5) |

| PuS | 2 (5.7) | 33 (94.3) |

| We will not recruit any person who is confirmed to have HIV | ||

| PrS | 211 (59.4) | 144 (40.6) |

| PuS | 17 (48.6) | 18 (51.4) |

| Applicants who are HIV positive do not deserve our sympathy and should not be short-listed for employment | ||

| PrS | 38 (10.9) | 309 (89.1) |

| PuS | 3 (8.1) | 34 (91.9) |

| Hiring or employing someone with HIV and AIDS is a waste of resources | ||

| PrS | 27 (9.1) | 270 (90.9) |

| PuS | 3 (9.4) | 29 (90.6) |

| Applicants should be asked to go for screening without their consent and prior notice by their prospective employer | ||

| PrS | 81 (26.7) | 222 (73.3) |

| PuS | 4 (13.8) | 25 (86.2) |

| All employers should ensure that persons they want to employ or hire are screened for HIV and AIDS before they are employed | ||

| PrS | 176 (56.2) | 137 (43.8) |

| PuS | 13 (44.8) | 16 (55.2) |

[Private Sector (PrS) n = 363; Public Sector (PuS) n = 37]

Table 2.

Past HIV/AIDS-related prevention and treatment activities carried out by participating organisations/employers of labour

| Activity | Yes No (%) | No No (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Organized a seminar/workshop or any educational programme on HIV and AIDS for workers | ||

| PrS | 163 (44.9) | 200 (55.1) |

| PuS | 16 (43.2) | 21 (56.8) |

| Discussed with workers or their union about what can be done to prevent HIV and AIDS among them | ||

| PrS | 178 (49.0) | 185 (51.0) |

| PuS | 26 (70.3) | 11 (29.7) |

| Informed workers about sources of information about HIV and AIDS | ||

| PrS | 211 (58.1) | 152 (41.9) |

| PuS | 32 (86.5) | 5 (13.5) |

| Made educational materials that can help increase workers' knowledge about HIV and AIDS available to them: | ||

| PrS | 177 (48.9) | 185 (51.1) |

| PuS | 22 (59.5) | 15 (40.5) |

| Required mandatory test for HIV | ||

| PrS | 129 (35.6) | 233 (64.4) |

| PuS | 14 (37.8) | 23 (62.2) |

| Informed employees to disclose their HIV status | ||

| PrS | 138 (38.0) | 225 (62.0) |

| PuS | 16 (43.2) | 21 (56.8) |

| Counselled any of your workers to go for HIV test | ||

| PrS | 182 (50.4) | 179 (49.6) |

| PuS | 24 (64.9) | 13 (35.1) |

[Private Sector (PrS) n = 363; Public Sector (PuS) n = 37]

Table 3.

HIV/AIDS policy & activities in workplaces that would be supported by the respondents

| Policy/activity | Private Sector (n=362) No (%) | Public Sector (n=38) No (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Activities to prevent the spread of HIV | ||

| Conduct seminar/workshop | 94 (26.0) | 9 (23.7) |

| Provide sex education | 254 (70.2) | 26 (68.4) |

| Activities that will be done when a staff has contracted HIV | ||

| Provision of medication | 213 (58.8) | 23 (60.5) |

| Preventing stigmatisation | 132 (36.5) | 12 (31.6) |

| Desirability of HIV prevention programme in workplace | ||

| Yes | 266 (73.5) | 30 (78.9) |

| No | 84 (23.2) | 3 (7.9) |

| Type of programme designed to prevent HIV in workplaces | ||

| Seminar/workshop to educate workers | 131 (36.2) | 15 (39.5) |

| Management & treatment of the disease condition | 26 (7.2) | 2 (5.3) |

| Periodic screening without prior notice | 10 (3.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| Improvement in staff social welfare package | 47 (13.0) | 5 (13.2) |

| Enlightenment campaign | 52 (14.4) | 7 (18.4) |

| Suggested financier of programme aimed at preventing HIV transmission in workplaces | ||

| Management | 84 (23.2) | 4 (10.5) |

| Government | 31 (8.6) | 3 (7.9) |

| Donor agencies | 160 (44.2) | 24 (63.2) |

| Labour union | 78 (21.5) | 4 (10.5) |

| Availability of HIV and AIDS policy in the participating organisations | ||

| Yes | 24 (6.6) | 7 (18.4) |

| No | 321 (88.7) | 25 (65.8) |

| Reasons for not having policy on HIV and AIDS | ||

| Everybody should be treated equally | 258 (71.3) | 24 (63.2) |

| Feel unconcern about the PLWHA | 90 (24.9) | 9 (23.7) |

| Medium through which workers were made to be aware of the policy | ||

| Through appointment letter | 215 (59.4) | 26 (68.4) |

| Through official bulletins | 117 (32.3) | 8 (21.0) |

| Implementation of organisation's policy on HIV and AIDS | ||

| Yes | 10 (2.8) | 7 (18.4) |

| No | 9 (2.5) | 2 (5.3) |

Table 4.

Factors that may influence the behavioural intentions of respondents towards workers and applicants who are living with HIV and AIDS

| Factors | Possibility of healthy looking person to have HIV | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Yes No (%) | No No (%) | X2 | p-value |

| Male | 244 (89.4) | 29 (10.6) | 2.765 | 0.096 |

| Female | 120 (94.5) | 7 (5.5) | ||

| Highest level of education | ||||

| Up to Primary | 16 (84.2) | 3 (15.8) | ||

| Secondary | 67 (88.2) | 9 (11.8) | 6.745 | 0.080 |

| Bachelor/HND | 192 (94.6) | 11 (5.4) | ||

| Postgraduate | 89 (87.3) | 9 (12.7) | ||

| Work experience | ||||

| 1 – 5 years | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | ||

| 6 – 10 years | 135 (91.2) | 13 (8.8) | ||

| 11 – 15 years | 93 (94.9) | 5 (5.1) | 7.805 | 0.099 |

| 16 – 20 years | 38 (82.6) | 8 (17.4) | ||

| 21 years above | 91 (91.9) | 8 (8.1) | ||

| Religion | ||||

| Christianity | 255 (91.1) | 25 (8.9) | ||

| Islam | 95 (90.5) | 10 (9.5) | 0.137 | 0.934 |

| Traditional religion | 14 (93.3) | 1 (9.0) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Currently not married | 123 (91.8) | 11 (8.2) | ||

| Currently married | 241 (90.6) | 25 (9.4) | 0.154 | 0.695 |

Table 5.

Respondents' socio-demographic characteristics and attitudinal disposition of respondents towards workers and applicants who are living with HIV and AIDS

| Attitudinal disposition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic Sex | Negative No (%) | Positive No (%) | X2 | p-value |

| Male | 127 (46.5) | 146 (53.5) | 0.361 | 0.548 |

| Female | 55 (43.3) | 72 (56.7) | ||

| Highest level of education | ||||

| Up to Primary | 11 (57.9) | 8 (42.1) | ||

| Secondary | 34 (44.7) | 42 (55.3) | 16.096 | 0.001 |

| Bachelor/HND | 107 (52.7) | 96 (47.3) | ||

| Postgraduate | 30 (29.4) | 72 (70.6) | ||

| Work experience | ||||

| 1 – 5 years | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | ||

| 6 – 10 years | 74 (50.0) | 74 (50.0) | ||

| 11 – 15 years | 31 (31.6) | 67 (68.4) | 13.121 | 0.011 |

| 16 – 20 years | 23 (50.0) | 23 (50.0) | ||

| 21 years above | 52 (52.5) | 47 (47.5) | ||

| Religion | ||||

| Christianity | 131 (46.8) | 149 (53.2) | ||

| Islam | 45 (42.9) | 60 (57.1) | 0.665 | 0.717 |

| Traditional religion | 6 (40.0) | 9 (60.0) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Currently not married | 78 (58.2) | 56 (41.8) | 13.744 | 0.001 |

| Currently married | 104 (39.1) | 162 (60.9) | ||

Acknowledgement

Data analysis and writing of this paper was supported by the Medical Education Partnership Initiative in Nigeria (MEPIN) project funded by Fogarty International Centre, the Office of AIDS Research, and the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institute of Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and the Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator under Award Number R24TW008878. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding organizations.

References

- 1.Oshiname FO, Dipeolu O. Knowledge and Perception of Employers of Labour in Ibadan North Local Government Area about Staff and Applicants Living with HIV and AIDS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Sci. 2011;1(7):137–146. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dipeolu IO, Oshiname FO. Attitudinal Disposition and Behavioural Intentions of Employers of Labour in Ibadan North Local Government Area towards Staff and Applicants Living with HIV and AIDS. J. Basic. Appl. Sci. Res. 2012;2(5):4624–4632. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ntomba R. Zambian businesses grapple with AIDS. Africa Renewal. 2004;18(2):6. Also available at http://www.un.org/ecosocdev/geninfo/afrec/vol18no2/182zambia.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ngwena C. Constitutional values and HIV/AIDS in the workplace: reflections on Hoffman v South African Airways. Developing World Bioethics. 2001;1(1):42–56. doi: 10.1111/1471-8847.00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Academy for Educational Development (AED) Academy for Educational Development/Centre on AIDS & Community Health (COACH) Lagos, Nigeria: 2006. Managing HIV/AIDS in the Workplace. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abiola OG. Handbook on Ibadan North Local Government. Published for Ibadan North Local Government by Segab Press. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Bureau of Statistics . Annual Abstract of Statistics. National Bureau of Statistics; Federal Republic of Nigeria: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) Private sector development strategy. GN-2270-4-E.pdf. Washington, DC, USA: 2004. [June 20, 2012]. pp. 2–6. Available on http://www.iadb.org/sds/doc/GN-2270-4-E.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walters B. [June 20, 2012];Gender and Economics: An overview gender. 2005 Available at http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTGENDER/Resources/Walters.pdf.

- 10.World Health Organization . Gender mainstreaming for health managers: a practical approach. WHO Press, World Health Organization; 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green LW, Kruter MW. Health promotion: planning an educational and environmental approach. Mayfield Publishing Co.; California, USA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 12.AVERTing HIV and AIDS (AVERT) [March 2005];Forms of HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination. Available at http://www.avert.org/aidsstigma.htm; http://www.avert.org/stigma%20discrimination%20attitudes%20to%20HIV%20&%20AI.

- 13.World Economic Forum [March 2014];Nigeria Business Coalition against AIDS (NIBUCAA) profile. 2005 Available at http://www.weforum.org/pdf/GHI/Nigeria.pdf.

- 14.Rosen S. What makes Nigerian manufacturing firms take action on HIV / AIDS? World Bank, Knowledge and Learning Centre; Washington, D.C. USA.: Jan, 2002. p. 4. (Private Sector and Infrastructure No. 199) Also available at http://www.wds.worldbank.org/servlet/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2002/03/29/000094946_02032104054244/Rendered/PDF/multi0page.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Labour Organisation (ILO) An ILO code of practice on HIV/AIDS and the world of work. A publication of the International Labour Organisation; Geneva, Switzerland: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Action Committee on HIV/AIDS (NACA) HIV/AIDS Emergency Action Plan (HEAP) A publication of the Nigerian National Action Committee on HIV/AIDS; Abuja, Nigeria: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Together we can: Leadership in a world of AIDS. Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]