Abstract

Relationship dynamics develop early in life and are influenced by social environments. STI/HIV prevention programs need to consider romantic relationship dynamics that contribute to sexual health. The aim of this study was to examine monogamous patterns, commitment, and trust in African American adolescent romantic relationships. The authors also focused on the differences in these dynamics between and within gender. The way that such dynamics interplay in romantic relationships has the potential to influence STI/HIV acquisition risk. In-depth interviews were conducted with 28 African American adolescents aged 14 to 21 living in San Francisco. Our results discuss data related to monogamous behaviors, expectations, and values; trust and respect in romantic relationships; commitment to romantic relationships; and outcomes of mismatched relationship expectations. Incorporating gender-specific romantic relationships dynamics can enhance the effectiveness of prevention programs.

Keywords: emerging adulthood/adult transition, race/ethnicity, African American, sexual behavior, HIV/STI

STI/HIV rates among African American youth are higher than among any other adolescent group in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010). Many African American adolescents living in urban areas have poor access to health care; this, compounded with sexual risk behaviors, such as early age at sexual intercourse and frequent sex without condoms, puts African American youth at high risk for STIs/HIV (Santelli, Lowry, Brener, & Leah, 2000). To date, STI/HIV adolescent-specific prevention programs have demonstrated moderate efficacy (Johnson, Scott-Sheldon, Huedo-Medina, & Carey, 2011). Prevention efficacy can be increased when programs are ecologically founded (DiClemente, Salazar, & Crosby, 2007; Johnson et al., 2009; Logan, Cole, & Leukefeld, 2002) and consider relationship dynamics and gender norms that influence risky sexual behaviors (e.g., DiClemente et al., 2004; Dworkin, Beckford, & Ehrhardt, 2007; Dworkin, Exner, Melendez, Hoffman, & Ehrhardt, 2006).

Forming romantic relationships is often considered critical to adolescent development (Furman & Shaffer, 2003; Sullivan, 1953), and adolescents explore their own and their partners’ sexual desires, expectations, and values in romantic connections (Florsheim, 2003; Furman & Shaffer, 2003). Adolescent romantic relationship dynamics, then, have a significant impact on sexual health (Furman & Shaffer, 2003). For this reason, adolescent STI/HIV prevention may be improved if programs focused on reinforcing dynamics within romantic relationships that may lead to positive outcomes (e.g., earning trust in a relationship so that mutual monogamy can easily be negotiated). To date, programs have largely focused on preventing potentially risky behaviors. Gender differences in behaviors and expectations may affect protective relationship dynamics in heterosexual relationships (Tolman, Striepe, & Harmon, 2003). Although gendered behaviors and expectations may also affect same-sex romantic relationships (Barber, 2006), and further research in this area is needed, the current research focuses on the impact gender differences have on opposite-sex relationships.

Although males and females often appreciate the intimacy that can be a part of romantic relationships (Giordano, Manning, & Longmore, 2006), generally males are socialized to put greater emphasis on sex and females are socialized to place greater emphasis on building strong and intimate romantic connections (Anderson, 1989; Eisler & Hersen, 2000; Manning, Giordano, & Longmore, 2006). Such binary categorizations about gender may reflect an oversimplification of the complicated nature of heterosexual romantic relationships, as some males and females do not conform to typical gender role boundaries and socialized categories (Riehman, Wechserg, Francis, Moore, & Morgan-Lopez, 2006). These categorizations, however, may help explain gendered sexual health behaviors. For instance, African American female adolescents prioritize intimacy over condom use in romantic relationships, and males prioritize sexual prowess over STI/HIV-related protective behaviors (Kerrigan et al., 2007). When males and females enter a romantic relationship with different expectations, safer sex negotiation, including an agreement upon mutual monogamy, can be difficult. With minimal or no safer sex discussion, adolescents are at risk for STIs/HIV (Noar, Carlyle, & Cole, 2006). Just as understanding possible gendered relationship dynamics that contribute to risky behaviors and lead to STI acquisition is imperative, so is the interplay between potentially protective and risky dynamics. Integrating protective factors (e.g., monogamy, commitment, and trust) into prevention may be an effective program supplement. The goal of this qualitative study was to explore urban, heterosexual, African American adolescent romantic relationships, and their gendered nature, examining risky and protective dynamics. In particular, the study focused on the impact commitment and trust have on monogamous patterns.

Monogamy and Its Gendered Nature

When two individuals are mutually monogamous by having sex with only each other during the time of their relationships (Schmookler & Bursik, 2007; Weaver & Woolard, 2008) and are free from STIs/HIV when they enter the relationship, they are at zero risk for STI/HIV acquisition from sexual intercourse. When either partner has a concurrent partnership, or is serially monogamous by having one exclusive partner after the next, the risk of STI/HIV transmission is increased when STIs are prevalent (Eames & Keeling, 2004; Misovich, Fisher, & Fisher, 1997; Pinkerton & Abramson, 1993). Serial monogamy and concurrency are routinely considered in STI/HIV prevention (Bauch & Rand, 2000; Drumright, Gorbach, & Holmes, 2004; Kelley, Borawski, Flocke, & Keen, 2003). Program efficacy may be increased if characteristics of the gendered nature of sexuality that potentially influence monogamy patterns are considered (Canin, Dolcini, & Adler, 1999; Sclafane et al., 2005; Tolman et al., 2003).

Males, including young, urban African American males, practice monogamy less frequently than females (Giordano, Manning, & Longmore, 2005; Harper, Gannon, Watson, Catania, & Dolcini, 2004; Kerrigan et al., 2007). The double standard that encourages multiple partnerships for African American males and monogamy for females (Anderson, 1989, 1992, 1999; Eyre, Auerswald, Hoffman, & Millstein, 1998; Harper et al., 2004) may stem in part from conflicting gender values and behavioral norms related to monogamy. These norms can encourage male control in heterosexual relationships (Levant & Pollack, 1995), and in turn, may leave females powerless to negotiate safer sex practices, such as mutual monogamy. Mutual monogamy as a safer sex practice may be related to commitment and trust levels in a relationship.

The Interplay of Commitment, Monogamy, and Trust

Interpersonal romantic commitment is generally considered a pledge to stay in a relationship (Arriaga & Agnew, 2001). Relationship commitment is thought to be dependent on four factors: (a) psychological attachment, (b) desire for relationship longevity, (c) intention to stay, and (d) the inability to find another partner who meets his or her needs (Rusbult & Buunk, 1993). If all factors are high for both people in the relationship, the couple is likely committed and mutually monogamous. Thus, a relationship that lacks these elements is apt to be noncommittal (Buunk & Bakker, 1997) and nonmonogamous (Riehman et al., 2006). Although the focus of this article was not to examine each of Rusbult and Buunk's commitment factors in African American adolescent relationships, the model did guide the researchers in conceptualizing romantic commitment. Commitment and monogamy are seemingly related relationship dynamics that may vary substantially by gender among African American adolescents.

African American adolescent males sometimes approach sexual concurrency as a kind of game and separate values of love and commitment from sex (Anderson, 1989). On the contrary, female adolescents, regardless of race or ethnicity, tend to attach values of love and romance to sexual relationships and view sex as a personal and intimate connection (Maccoby, 1990). Aside from Anderson and Maccoby's work, studies that have considered the differences (or similarities) in commitment according to gender are older, were not conducted with STI/HIV prevention as the focus, did not include African American youth (McCabe, 1987; Schmidt, Klusmann, Zeitzschel, & Lange, 1994), or were not conducted in the United States (Schmidt et al., 1994). Further exploration into the gendered nature of commitment as it relates to monogamy in African American adolescent romantic relationships is needed. And, further exploration into romantic trust as it is experienced by African American adolescents, and how it is associated with their commitment and monogamy patterns, is also needed.

Lack of monogamy and commitment may be related to mistrust in a relationship. Trust is commonly thought of as a belief that another person is, and will continue to be, reliable (Cook, 2001). Trust can increase commitment in a romantic relationship, break down personal guards, and make a person feel invulnerable (Larzelere & Huston, 1980; Stinnett & Walterns, 1977). From a psychological perspective then, trust can deepen intimacy and sustain a relationship (Larzelere & Huston, 1980), and may increase the likelihood of mutual monogamy (Bauman & Berman, 2005). Interpersonal trust may be difficult to attain in heterosexual relationships when males and females have different expectations, and when they behave differently in relationships.

From a young age, females generally tend to be more honest than males (Betts & Rotenberg, 2009). Although few studies have examined how childhood gender differences in honest behavior impact gendered trust patterns in romantic relationships later in life, there is evidence to suggest these gender differences lead to mistrust in adult romantic relationships. It has been suggested that among low-income adult populations, there is little trust between males and females, and this gender mistrust is thought to be related to relationship instability and lower successful marriage rates (Carlson, McLanahan, & England, 2004; Furstenberg, 2001). Such romantic partner mistrust may start in adolescent romantic relationships. When there is mistrust in the relationship, mutual monogamy and mutual commitment may be difficult to achieve. Individuals who are in mutually trusting, monogamous, and committed relationships may be at lower risk for STI/HIV acquisition than individuals who are in relationships that lack such relationship dynamics. Trust appears to play a role in monogamy and commitment in romantic relationships, but little research has explored the role it plays in urban African American adolescents’ relationships, or the particular influence it can have on sexual health behaviors.

Various factors can influence adolescent sexual health, including a youth's peers (Kapungu et al., 2010), educational experiences (Dolcini, Catania, Harper, Boyer, & Richards, 2012), friendship groups (Dolcini, 2002), family (Harper et al., 2012), and romantic partner dynamics (Manning, Longmore, & Giordano, 2000). In addition, factors may vary by gender. Although romantic dynamics (including commitment and trust) may influence adolescent sexual health (including monogamous and multiple sex partner behaviors), research has only just begun to explore in depth this complex association. Thus, the current study aimed to provide a nuanced description of the association between commitment, trust, and monogamy patterns among urban African American adolescents. Furthermore, the aim was to examine the differences in these dynamics between and within gender.

Methods

Participants

Participants for this study were 28 African American adolescents aged 14 to 21 (male = 13, female = 15; see Table 1), who lived in low-income neighborhoods of San Francisco and who were sexually experienced (with the exception of one male). San Francisco's recent STI estimates report significantly higher rates of STIs among African American teens aged 15 to 19 when compared to STI rates of White or Hispanic adolescents in the same age group (Darbes, Crepaz, Lyles, Kennedy, & Rutherford, 2008).

Table 1.

Participants’ Ages and Current Monogamous Status

| Pseudonym | Age | Monogamous | Not monogamous |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males (n = 13) | |||

| Andre | 15 | √ | |

| Carl | 15c | √ | |

| Erica | 16 | √ | |

| Rodneya | 16 | √ | |

| Samuel | 16 | √ | |

| James | 17 | √ | |

| Scottb | 17 | — | |

| Deon | 17 | √ | |

| Louis | 18 | √ | |

| Michael | 18 | √ | |

| Amir | 18 | √ | |

| Ty | 19 | √ | |

| Darrel | 19 | √ | |

| Females (n = 15) | |||

| Kim | 14 | √ | |

| Tasha | 15 | √ | |

| Sarah | 15 | √ | |

| Shawna | 15 | √ | |

| Nisha | 16 | √ | |

| Nicoled | 16 | — | |

| Kayla | 17 | √ | |

| Angela | 18 | √ | |

| Brittany | 18 | √ | |

| Amber | 18 | √ | |

| Lisa | 18 | √ | |

| Dominique | 19 | √ | |

| Whitneyd | 19 | — | |

| Janelle | 20 | √ | |

| Mila | 21 | √ |

Respondent engaged in oral, not vaginal intercourse.

Not sexually experienced.

Age was not reported, but interview notes indicate participant's age as older than 15.

No current sex partners.

Procedures

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the sponsoring institution. Recruitment took place through community outreach and snowball sampling. Participants 18 and older provided informed consent; participants younger than age 18 provided assent and parent/guardian consent. Trained, gender-matched study staff interviewed participants in a private location. At the completion of the 1- to 2-hour interview, youth received remuneration in the form of cash.

The interview guide, which is available in full from the author, queried about a range of topics related to romantic experiences and attitudes and included specific topics related to sex, dating, monogamy, and multiple partner relationships (e.g., “Do you have a boyfriend/girlfriend? Was there a point in the relationship when you two became monogamous to each other?”). Adolescents who endorsed being in a dyadic relationship and engaging in sexual behavior only with their dyadic pair at the time of data collection were considered to be in a mutually monogamous relationship (Schmookler & Bursik, 2007; Weaver & Woolard, 2008). When the respondent or the respondent's sex partner had a concurrent sexual partner at any point during the time of the relationship, the participant was considered not to be in a mutually monogamous relationship. Collecting data that related to monogamous status from both participants in a sexual relationship (or all partners in a concurrent sexual network) would help in providing the most accurate account of relationships. The interview guide, however, did not collect information from both individuals in the dyadic partnership (or other partners connected to the participants’ sexual networks); thus, we relied on the respondents’ perceptions of their partners’ monogamous status. There is a possibility that some youths’ perceptions were incorrect (e.g., they may have perceived their relationship to be mutual monogamous when it was not).

Data Analysis

A phenomenological framework was used to analyze the data; this framework focuses the analysis on describing the shared experiences of the participants as the experiences emerge as a phenomenon (Creswell, 2009). The interviews were entered into Max-QDA-10 (Kuckartz, 2010) for the purpose of classifying, sorting, and retrieving text (Berg, 2007; Kuckartz, 2010; Patton, 2002). In line with the phenomenological framework, we included a variety of adolescents’ voices in our results to ensure that conceptual “outliers” were not silenced by the more dominant voices. Thus, we included all voiced themes that emerged and not only those endorsed by the majority of adolescents (Creswell, 2009; Patton, 2002). Using deductive and inductive coding, dominant and subordinate themes and subthemes were identified in the data (Creswell, 2009; Patton, 2002). The deductive approach identifies codes that reflect the literature and are put forth before data analysis begins, and the inductive approach allows for new themes to emerge during the analysis (Berg, 2007; Patton, 2002). Once the codes were determined, a final codebook was created. Using the codebook, the analytic team read the transcripts at least 3 times and coded the data. To ensure reliability, a second trained researcher read and coded a randomly selected 20% of the transcripts. Coding discrepancies were discussed and researchers came to agreement about how to code all sections. Following this, male and female interview transcripts were examined for within- and across-gender variation (Patton, 2002), and final themes and subthemes were settled on accordingly. Finally, patterns that emerged across all participants were determined with a cross-case analysis.

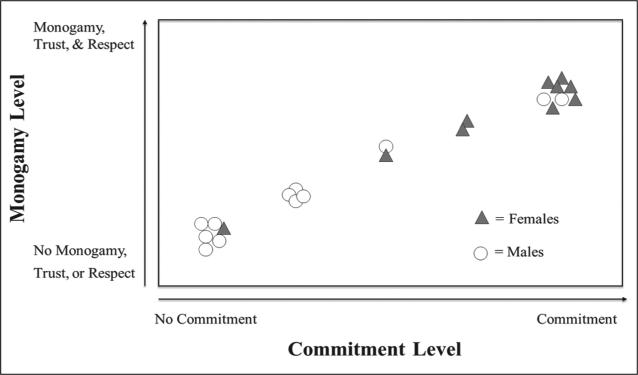

During the cross-case analysis, it became clear that relationship dynamics were interrelated. In order to understand the interplay among relationship concepts, Figure 1 was developed. Monogamy, trust, and respect were generally thought to be closely related; thus, these concepts are placed together on the Y axis of the figure. Although commitment related to these concepts, it varied considerably across the sample, and thus, is placed along the X axis.

Figure 1. Monogamy and commitment on a continuum.

Note: Model illustrates adolescents’ monogamy and commitment in relationships. Monogamy, trust, and respect are all illustrated on the Y axis. Commitment is depicted on the X axis. Males and females fall somewhere along the commitment continuum.

Respondents were placed on the model according to their self-reported levels of trust, respect, and commitment, and whether or not they were monogamous. Monogamous adolescents reporting high levels of trusting and respectful behavior, and who felt committed to their partner, were placed in the upper-right-hand corner. Nonmonogamous adolescents reporting low levels of trusting and respectful behavior, and who did not feel committed to any one partner, were placed in the lower-left-hand corner. Adolescents who were either monogamous in the past or were considering monogamy with a current partner, who expressed some level of trusting and respectful behavior, and who were ambivalent about commitment were placed along the continuum between “no commitment” and “commitment,” and between “no monogamy, trust, or respect,” and “monogamy, trust, and respect.”

Results

The results describe adolescent relationship dynamics that affect monogamy. Characteristics of monogamy are described, including variations within and across gender related to sexual behaviors and relationship expectations, attitudes, and values. The data presented relate to (a) monogamous behaviors, expectations, and values, (b) trust and respect in romantic relationships, (c) commitment to romantic relationships, and (d) outcomes of mismatched relationship expectations. Tables 2 to 5 describe these themes as well as subthemes and supporting quotes from the data, and the tables are referred to throughout the Results section. Both the prominent and the subordinate themes are presented in the results. Respondents are identified with gender-specific pseudonyms.

Table 2.

Subthemes for Monogamy

| Number | Subtheme | Supporting quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Ml | Multiple concurrent partners valued by males | Most [guys] think they're players, pimps . . . if you're a guy you just . . . have to have more than one female. One as your wifey and one as somebody you just want to just have sex with. . . . Most of them think that's a man's thing to do. (Amir, male, age 18, multiple partners) |

| N_ is dogs. They gonna get on another girl if they like another girl. Because they not trying to settle down. They ain't got no rings on they fingers, so if they see something they like they gonna get it. (Sarah, female, age 15, multiple partners) | ||

| They're looking up to the other brothers . . . [with] five girls . . . it's like a little domino effect. . . . Most young people want to do what their friends do . . . they want to look good . . . it feels good for your friend to say, “Oh, you doing this? Right on.” You feel like the man out there. And most males, they like to feel like, “Okay, I'm strong. I got a way about that. Ain't nobody mess with me . . . .” Makes them feel like they the “man,” manhood, that's what they think. I'm a man now. I got all these girls. (Michael, male, age l8, monogamous) | ||

| Most [guys] is like, they want to be like, “Yeah, I had her. Um hum. So who you going with? Yep, I f_ her, too. Woop de woop de woo.” Just to make theyself seem big, and they hit it. (Kim, female, age 14, monogamous) | ||

| M2 | Multiple sex partners kept a “secret” | You have to hide it, like a player, you have to hide your stuff. . . . If you gonna have more than one female, you have to hide it, because most girls be like, uh uh. They'll be like, I ain't going for that. You stick with me. That's most females. . . . I've never met a female who . . . would not want to be committed to that one person, to that one male. . . . You have to get her to think she's the only one. (Michael, male, age l8, monogamous) |

| He got other girlfriends . . . I already knew this. But . . . he tried to . . . hide it from me, and that's another thing that turned me off about him, because when you try to hide stuff from me, I'm like finding it out. And you know the ‘jects talk, by theyself. So without you even telling nobody, somebody else still know. So it get around, so of course I was gonna find out and what I don't like is that he tried to hide shit from me. (Sarah, female, age l5, multiple partners) | ||

| M3 | Males valued monogamous females | I really do think females is into [sex] as the guys is [in that they like sex]. But they don't put it out as much. Like just like people say, the pimps and the whores thing. A female is a whore if she sleep with more than two, three guys. But if a guy sleep with more than two, three girls, he a pimp. (Samuel, age 16, multiple partners) |

| The guy expect the girl not to cheat on him. The guy expect that let the girl know to be honest with him at all times. (Andre, age l5, multiple partners) |

Table 5.

Subthemes for Outcomes of Mismatched Relationship Expectations

| Number | Subtheme | Supporting quotes |

|---|---|---|

| O1 | Females experienced loss when their hopes of mutual monogamy were unmet | My boyfriend, he had sex with another girl. . . . I guess he thought I wasn't gonna find out. But everybody talks . . . my friends didn't want to hurt [my] feelings, and . . . didn't know how to tell [me]. But my worst enemy telling me, and I'm thinking. . . . I know she laughing her ass off. Because this is my n_, and it make it seem like he don't like me enough to want to be faithful to me or whatever. (Kim, female, age 14) |

| I'd rather be the mistress on the side and know about everything than be the main one. Not in the dark about everything. . . . He can be so open and honest with me. And I don't judge him about it. I think that's what he kinda likes. (Dominique, female, age 19) | ||

| O2 | Two males endorsed regret for being nonmonogamous | I don't like [cheating] too much. I don't like that guilty conscience, like trying to keep . . . yourself from being caught. (Samuel, male, age 15) |

| I just [felt cheating on my girlfriend was] weird. I was like, oh, damn. Cheat on my girl. She gonna find out. . . . So you get nervous . . . afterwards. I thought about it like, damn, I don't believe I'm doing this with her. (Andre, male, age 15) |

Monogamous Behaviors, Expectations, and Values

As anticipated, monogamy was common for females and uncommon for males (females = 13, monogamous males = 2, monogamous; see Table 1). Younger males (i.e., aged 15 to 16) thought that having multiple partners increased social status. Older males expressed an understanding that love and respect could be gained in mutually monogamous relationships and viewed monogamy as a choice made by older, more mature males. Although male respondents believed age should be associated with monogamous behaviors, their own behaviors did not reflect this perception. Females, regardless of age, aspired to find a mutually monogamous relationship.

Although males and females had different behavioral norms related to monogamy, both viewed commitment, trust, and respect as elements that were related to monogamy. Figure 1 presents the interrelationship among these concepts as they emerged in our study. Throughout the results, the figure is referenced, and a rationale for the “scoring,” or placement of respondents on the continuum, is provided (as described in “Methods”). Specific to monogamy, females cluster at the upper right of the figure because many were monogamous, whereas males cluster toward the lower left, reflecting their nonmonogamy norm.

Subthemes of monogamy emerged, which relate to monogamy expectations and values, and are shown in Table 2. They are as follows: (a) having multiple concurrent partners was valued by males, (b) having multiple sex partners was kept a “secret,” and (c) males valued females who were monogamous. The male norm of engaging in sex with multiple partners was reinforced and valued by other males and acknowledged by females (Table 2, M1). Males sought recognition of their manhood and maximized their social status through multiple partnerships (Table 2, M1). At the same time, males tried to keep this behavior secret from females.

Males were aware that most female partners wanted them to be monogamous. Thus, males tried to keep information about additional partners a secret from other females. Attempts to keep behaviors a secret appeared to be a way of avoiding conflict with female partners and potentially keeping all of their sex partners (Table 2, M2). Keeping other partners a secret was largely unsuccessful because males talked about their sex partners with their male peers as a way to enhance their reputation and social status. Thus, females usually knew about the other sex partners and expected that their boyfriends were, or eventually would be, unfaithful (Table 2, M2).

In contrast to males, having only one partner at a time (i.e., monogamy) was the norm for females. Females valued monogamy because they experienced rejection from males and a loss of social status when they had concurrent partnerships. Males, whether or not monogamous themselves, respected and pursued romantic relationships with females who were monogamous and called females with multiple sex partners disparaging names, such as “whores” or “breezies” (Table 2, M3). Females were expected to remain monogamous, and they most often were.

Trust and Respect in Romantic Relationships

Both males and females valued trust and respect in romantic relationships. Table 3 shows three subthemes that emerged that related to these constructs: (a) Mutual monogamy is fundamental to a trusting and respectful relationship for males and females, (b) communication is important to males, and (c) monogamy and love are important to females. Males and females discussed trust and respect together with mutual monogamy. Because mutual monogamy was rare, trust and respect ideals were described but not often practiced. Males and females felt that if they were in a mutually monogamous relationship, it would be a trusting and respectful one (Table 3, TR1; and see Figure 1, upper-right corner).

Table 3.

Subthemes for Trust and Respect

| Number | Subtheme | Supporting quotes |

|---|---|---|

| TRI | Mutual monogamy is fundamental to trust and respect | A girlfriend is a somewhat thing that you work on. You develop it throughout weeks, days, or months. You develop trust and different things. . . . Let them know how a man feels sometimes. A girlfriend gotta listen . . . a girlfriend to me is a person that's right by your side. Loyal just to you just like you loyal to them. . . . And I treat a girlfriend like a girlfriend's supposed to be treated . . . with respect. You definitely gotta have responsibility. And just being there just to listen. Just to love. (Ty, male, age 19, multiple sex partners) |

| [My boyfriend] said [he was monogamous], but I don't believe it . . . [I want my relationship with him to develop] . . . honesty. Gotta earn each other's trust. Respect. (Amber, female, age 18) | ||

| TR2 | Communication is important to males | Yeah, a [girlfriend] gets respect. . . . A [girlfriend] . . . I can talk to you about whatever. And I don't mind telling [her] because I seen [she] understand. (Michael, male, age 18) |

| My relationship with my [main] girl is good, because I know we talk about, whatever she don't feel comfortable talking about, she'll tell me. And whenever she think that's unnecessary to do or something, or say, she'll tell me. . . . And you can trust her. She can trust you. (Andre, male, age 15) | ||

| TR3 | Monogamy and love are important to females | [I'm in love with my boyfriend] because if, I never met nobody like him. . . . I never met a guy that's just so, just so good to a woman. . . . That's why I said that I love him, because he's a good (i.e., monogamous) man. (Brittany, female, age 18) |

| I can trust [my boyfriend] more than like all these females around here, like and I don't even know. And he kept just showing like he loved me. I mean, a lot of people can show that they love you, but they can't really love you. . . . (Shawna, female, age 15) |

Although males and females felt that trust, respect, and mutual monogamy went hand in hand, each described the specifics of a respectful and trusting relationship differently. Males placed emphasis on communication, including the importance of needing to listen and be heard (Table 3, TR2). Only one female, Sarah, mentioned communication and respect in the same context; Sarah considered talking as an important dynamic of primary partner relationships: “[With my boyfriend] we kind of like really enjoy being with each other . . . enjoy each other's conversation . . . but with a friend you just f. . . .”

Generally, females were attracted to and felt respected by young men who were “good” to them (i.e., they did not cheat on them), expressed love, were trustworthy, and treated them differently than the social norm (i.e., nonmonogamous and untrustworthy; Table 3, TR3). In all, 4 of the 15 female participants were in mutually monogamous relationships, and although other females hoped for the same, they did not have it.

Commitment to Romantic Relationships

Figure 1 illustrates commitment on a continuum and shows the distinct gender differences in commitment. The females who had committed to their sex partners are represented on the right of the continuum; in contrast most males were noncommittal and fall on the left side of the continuum. Adolescents who had some level of investment in their sexual relationship but had not made a decision to stay in the relationship or to practice monogamy fall on the continuum between not committed and committed; most of the adolescents in this position were male. Table 4 illustrates four subthemes related to commitment: (a) females committed with the hopes that one day they would be in a mutually monogamous relationship; (b) mothers committed to fathers despite the relationship quality and father's commitment level; (c) by not committing to one female, males felt they would retain multiple partnership status; and (d) a few participants were irresolute about commitment.

Table 4.

Subthemes for Commitment

| Number | Subtheme | Supporting quotes |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | Females committed with hopes of mutually monogamy | Because [females] feel like well, I can get this one-night stand. Then he can just be my friendly thug. And he could be my actual n_. And this could be my boyfriend. This could be the man I love. (Kim, female, age 14, monogamous and committed) |

| I feel with a male is able to be more honest and more open with hisself and doing what he really want to do or act like he really act, then the really gonna feel you more. That's gonna make him more into you, basically. If you let him be who he really is. (Sarah, female, age 15, multiple partner and committed to her main partner) | ||

| C2 | Mothers committed to fathers despite relationship quality and father's commitment level | He said [he was monogamous], but I don't believe it. . . . Because his reputation [of a whore] and I still see him around females. And I just don't believe that he's just being with me. . . . I mean, it's just, I caught him too many times I know so many girls that he's gonna have sex with, especially since I've been pregnant and since I've had my baby. So I don't trust him. [But I'm in love with him] because, I mean, it's just been over a year. It's the longest I've ever messed with somebody and I felt like I have strong feelings for him. And I just, I don't know, I can't go without him. Everything I think about has to do with him. Our future, our baby, we have a baby together. . . . |

| Interviewer: So how would you like to see your relationship develop with him? | ||

| Amber: Honesty. Gotta earn each other's trust. Respect. (Amber, female, age 18, monogamous and committed) | ||

| Love to me means respect, not getting caught with no B's, not getting hit on. Respecting each other's mind, like telling each other the truth and not lying and not thing to keep stuff hid or behind each other. [And love is important to me] because love is like, it's like the intimates thing, you don't want to get hurt, and you don't want to get heartbroken. (Tasha, female, age 15) | ||

| C3 | Males retain multiple partnership status by not committing | Even though the girl wasn't my girlfriend, she was talking like she was. . . . It made it seem like I was cheating on her [because I had another sex partner at the time] even though I wasn't. She was just a friend. (Samuel, male, age 16) |

| I have a girlfriend and I think our relationship, it's cool to be little, like a little 16-year-old teen relationship. I mean, I don't, I mean, just take it slow, because like I said, I got my whole life ahead of me. Maybe I still be with her; maybe I'll find somebody else. But we still talk, or whatever. We just go out. That's it. (Eric, male, age 16) | ||

| C4 | A few adolescents were irresolute about commitment | She's waiting on me to make that step. But I don't really know right now because it's kind a scary. . . . Like giving up everything and just being with one person. Kinda hard . . . I got too many needs. And she can't really please them all. (Darrel, male, age 19, multiple sex partners and not committed) |

| If I would have left my boyfriend, [my sex partner] would have became my boyfriend . . . but I was really ready [to commit to my boyfriend]. I think I should have not been with my boyfriend. . . . I'm trying to make it work and try to hold, but it wasn't working. But if I would have just like [broke up with him] . . . it's hard to let go sometimes. (Whitney, female, age 19, no current sex partners, not committed) |

Females committed to relationships with the hopes that one day their partner would reciprocate with commitment. By having sex with and committing to one partner, and by giving him freedom to have other sex partners, some females hoped to increase their chances of eventually finding a committed, loving, and mutually monogamous relationship (Table 4, C1)

Two female participants were mothers and endorsed being monogamous and committing to their child's father. They appeared to view their relationships as loving, even when their relationship experiences contradicted their description of love. For instance, Amber identified the father of her child as her boyfriend, she appeared to commit to him, and she practiced monogamy with him. For her, respect and trust were characteristic of love. Despite the father of her child declaring he was monogamous, she believed he had other partners. She did not think their relationship was caring, trusting, or respectful but still said she loved him. Amber hoped that if she stayed committed to the father of her child, the relationship would develop into a respectful, trusting one (Table 4, C2). Tasha was also a mother who was committed to the father of her child; she felt she loved him and hoped to make the relationship last. However, Tasha's family encouraged her to leave him and felt he disrespected her. Tasha's relationship experience also contradicted her perception of love (Table 4, C2).

Of the 15 female participants, only Sarah reported a reluctance to commit to a romantic relationship: “I think people should be faithful, but at the same tone, kind of like f . . . that faithful shit. That shit don't work . . . he gonna get tired and he gonna do what he gonna do anyway.” Sarah's lack of commitment appeared to be a way of protecting herself against being hurt or losing her boyfriend when he cheated, since males were less likely to be committal or monogamous.

Unlike females, the majority of males had no intention to commit to one sexual partner. They were noncommittal because this allowed them the freedom to have multiple partners who fulfilled their various sexual desires. Male social norms supported multiple partnerships, and some males felt they gained status by having multiple partnerships. In addition, males who were not in a mutually monogamous relationship rarely discussed aspirations for a trusting and respectful relationship. Samuel had a girlfriend and other sex partners but was unwilling to commit to any one partner. Eric was in a mutually monogamous relationship but was noncommittal to a future with his girlfriend (Table 4, C3).

Most males were noncommittal and had multiple partners, and most females were committed and monogamous. A few participants, however, were irresolute about commitment and neither practiced monogamy with their main sexual partner. Darrel was indecisive about committing to his girlfriend because he feared unmet needs, though he was aware of her desire for the relationship to be exclusive and committed. Whitney was noncommittal with her new sex partner because she hoped that another relationship with her relatively long-term, yet noncommittal, boyfriend would eventually lead to mutual monogamy and commitment. For her, having another sex partner was a way to cope with her disappointment with her boyfriend. Although Whitney ultimately wanted to commit, her boyfriend was unwilling, similar to most male participants (Table 4, C4).

Outcomes of Mismatched Relationship Expectations

Gender differences emerged in the data that related to monogamous behaviors, expectations, and hopes; these differences were associated with different emotional reactions for females and males. Table 5 illustrates subthemes related to outcomes of mismatched relationship expectations: (a) females felt a sense of loss when their partners were nonmonogamous even though they did not expect monogamy from them, and (b) two males expressed guilt or anxiety for being nonmonogamous even though the norm for males was nonmonogamy.

Females felt loss in various domains when their hopes of being in a mutual monogamous relationship were unmet. Kim experienced the loss of her partner's faithfulness when she heard neighborhood rumors that he was sleeping around. She felt that only her enemies would tell her about her boyfriend's cheating and that turning a blind eye to his multiple partnerships was better than knowing the truth. Other females expressed feeling a loss of trust, a future together, or their virginity when they found out their boyfriends had other sex partners (Table 5, O1).

Although most females in the sample were unhappy when they discovered their partners’ secret of nonmonogamy, one respondent expressed a desire for honesty over exclusiveness. Dominique felt that the honesty that came with being accepting of her male's multiple partnerships was better than the dishonesty that came with being a main partner. She said she would “. . . rather be the mistress on the side and know about everything than be the main [sex partner].”

In contrast to females, males were infrequently with females who were nonmonogamous, nor did males report feelings of loss. James was the only male who reported having a girlfriend who cheated on him. He reacted to her nonmonogamy by ending the relationship: “I just felt [I was in love]. It just happened. We just fell in love with each other. Because we went out for three years . . . [then] she cheated on me. And I broke up with her.” James’ termination of the relationship because it did meet his expectations contrasts with many females who were more inclined to commit to relationships even when their relationships did not meet their expectations.

Although few young men expressed remorse for engaging in multiple partnerships, two of them reported regret for having recently engaged in sexual behaviors with someone besides their main partner. Being unfaithful left them feeling guilty, anxious, and fearful of the consequences, and as a result, these two males endorsed intentions to remain monogamous (Table 5, O2).

Discussion

Our findings contribute to public health research because they consider the interplay of monogamy, trust, respect, and commitment in urban African American adolescents’ heterosexual romantic relationships. In particular, results suggest that urban African American males and females’ sexual partnering patterns and romantic relationship commitment levels are different, and yet, surprisingly, males and females had similar expectations of mutually monogamous relationships. Findings also suggest that males are confronted with contradictory gender norms, and females are aware of the contradiction.

These results provide a deeper understanding of the context of African American adolescents’ sexual behavior. Males often engaged in nonmonogamy but kept this behavior a secret from their sex partners. When a male engages in nonmonogamy and does not engage in safer sex with all of his partners, all individuals in the sexual network are at increased risk for STI/HIV acquisition when STIs/HIV are present (Eames & Keeling, 2004). When a female commits to, and is monogamous, with a male, she may trust him and not feel the need to protect herself from STIs/HIV by using condoms; this may be problematic when her partner is neither committed nor monogamous. Our results suggest that gender differences in relationship norms, expectations, and attitudes, and contradictory male gender norms, may threaten adolescents’ sexual health.

Gender Divergence: Sexual Partner Status and Commitment

The finding that African American males are infrequently monogamous and females are often monogamous (Giordano et al., 2005; Harper et al., 2004; Kerrigan et al., 2007), and African American youth are sometimes secretive about extra dyadic relationships (Bauman & Berman, 2005) corroborates previous research. Our findings are distinct from prior related research because we identified that males were confronted with contradictory norms. Although males kept their multiple partner status a secret from other female sex partners, they also talked with other males about their partners to gain social status. Males’ desire to keep multiple sex partners a secret was surpassed by their desire to meet gender role norms that expected them to have multiple partners.

Such an inconsistency in gendered expectations may be especially threatening to sexual health communication. If multiple partnerships increase males’ social status, and if males keep their extra dyadic partnerships a secret, then it may be difficult to openly discuss protective measures with a partner. Similarly, other research has found that social pressures hamper sexual health communication (Marston & King, 2006). When communication is minimal, males and their multiple female partners may be at increased risk for STI/HIV acquisition. Without communication, condom use is less likely (Noar et al., 2006).

Different from males, females were expected to remain monogamous, regardless of their partner's sexual behaviors. This finding substantiates prior research. Kerrigan and colleagues (2007) found that “strong” African American women were encouraged to “stick to one's man” and were expected to remain tolerant and accepting when their boyfriend was nonmonogamous. Males in Kerrigan and colleagues’ study often rejected females who failed to live up to this social expectation. Our findings are distinct from Kerrigan's research because females in our study were not only monogamous, they were also emotionally invested (i.e., committed) to partners who were nonmonogamous and noncommittal. The reasons for females’ commitment to less-than-ideal partners are complex.

First, females who feel social pressure to remain monogamous may also feel the pressure to emotionally invest (i.e., commit) themselves to males who do not meet their expectations. Second, females may commit to and remain monogamous with partners who are neither monogamous nor committed, because males who commit and who remain monogamous are hard to find. Finally, females may commit to relationships as a result of feeling connected to their partner after sex. Female adolescents have reported feeling that sex is a connecting and loving experience (Maccoby, 1990). If a female feels connected after engaging in sex even with a noncommittal partner, she may react by committing to this partner, especially if she feels the social pressure to do so, and if she has difficulty finding another more ideal partner. Clearly, females’ reasons for committing to a noncommittal partner are complex.

Males’ tendency to be noncommittal to any one sex partner is in keeping with prior research (Anderson, 1989). As found in Anderson's study, males had a proclivity to separate values of love and commitment from sex while engaging in multiple partnerships. Males may associate commitment with mutual monogamy, which may be unappealing. Since multiple partnerships seem to meet males’ sexual and social needs, committing to one partner may be less than desirable. Females and males were different when it came to their sexual behaviors and commitment levels, but their views converged with regard to trust and respect.

Gender Convergence: Mutually Monogamous Relationships Are Trusting and Respectful

Both males and females thought that trust and respect were part of mutually monogamous relationships. Respect was not directly queried in this study, but adolescents naturally discussed respect in conjunction with trust and monogamy. For males, communication was characteristic of a respectful, trusting, and monogamous relationship, but few males were actually in such relationships. Females described monogamous and trustworthy males as respectable and “good,” but respectable males were hard to find. Most males did not meet females’ ideals of respect. Even so, males appeared to understand the emotional maturity (i.e., trust, respect, and communication) associated with mutual monogamy. Some males believed that responsible, older, and more mature males were in mutually monogamous, trusting, loving, and respectful relationships, but this ideal did not match their current relationships. The belief that older males engage in monogamous behavior may not be true in reality because of the salient male gender norms that encourages multiple partnerships.

Adolescents postulated about trusting, respectful, and mutually monogamous relationships, but few adolescents were in such relationships. Gender role norms may help to explain why adolescents’ ideas of mutually monogamous relationships were not actually enacted. If males value nonmonogamy, then having multiple partnerships may override maintaining a trustworthy, respectable, and mutually monogamous romantic relationship. If females value trustworthy, respectable, and mutually monogamous relationship, but relationships with all these factors are difficult to find, they may settle for less-than-ideal relationships that lack these characteristics.

Living Up to Gender Role Norms

Males’ tendency toward multiple partnerships and being noncommittal and females’ tendency toward monogamy and commitment are in line with typical adolescent gender role norms (Eisler & Hersen, 2000; Kerrigan et al., 2007). Individuals may be especially inclined to conform to typical gender norms when they are salient (Schmookler & Bursik, 2007), or when the benefits of doing so are interpersonally rewarding (Sanchez, Fetterolf, & Rudman, 2012). Gender norms that relate to romantic relationships are salient (e.g., reinforced through media; Mussweiler & Forster, 2000). Lack of adherence to these norms can result in rejection. Thus, males and females may adhere to romantic norms to ensure companionship, and acceptance from peers (Sanchez et al., 2012; Tolman, 1994). Furthermore, psychological distress can result when individuals do not adhere to prominent gender roles (Pleck, Sonenstein, & Ku, 1993; Sanchez et al., 2012). For instance, males, including African American males, may not follow a natural desire to engage in intimate, monogamous, and committed romantic connections because doing so contradicts stereotypical “masculine” gender role norms that place an emphasis on sex (e.g., Anderson, 1989; Bowleg et al., 2011). Those who do not adhere to masculine norms may feel rejected (Bowleg et al., 2011).

The psychological distress that results from the pressure to adhere to these gender-specific behaviors and attitudes may be partially explained by Pleck's gender role strain (GRS) paradigm (Peleck, 1981), which suggests that behaviors are influenced by specific roles imposed on males and females. The paradigm states that individuals are expected to adhere to their culturally defined and gender-specific roles, or collectively, gender norms. Gender norms are not the result of an individual's psychological traits, but the outcome of cultural influence (Pleck, 1981; Richmond & Levant, 2003). Gender norms continually shift and change just as cultural norms do; thus, individuals are confronted with psychological distress as they navigate constantly shifting expectations put upon them (Pleck, 1981). Individuals who do not invest in and act on gender roles may receive inadequate social support because they are viewed as “different” from the norm; as a result, they may deal with psychological stress referred to as “gender role strain” (Pleck, 1981).

The GRS paradigm does not explicitly consider the implications of gender role impositions on females, but it does recognize that male and female gender roles uphold a patriarchal structure, such as that of the United States (Pleck, 1981; Richmond & Levant, 2003). Prior work, as well as the current findings, related to the GRS paradigm, may also apply to females. One assumption made by the paradigm is that rejecting gender-specific social impositions results in social condemnation (Pleck, 1981). This study's results showed that gender role norms supported multiple partners among males and encouraged females to remain monogamous so they would avoid rejection. In accordance with this paradigm, males and females appear to conform to gendered social expectations.

A second assumption made by the paradigm is that gender norms and expectations are inconsistent. This assumption is particularly applicable to males in our study, as they were confronted with contradictory social norms that complicated the notion that multiple partnerships affirmed high social status. Males who had multiple partnerships were looked up to but were also expected to keep these partnerships a secret from females, and males who were older and more responsible were expected to be monogamous. Because males were confronted with conflicting social expectations and responsibilities, they may have behaved according to the prominent social expectation of having multiple partnerships instead of the less popular expectation of being responsible and monogamous. Being secretive about multiple partnerships may have also helped males live up to these contradictory expectations.

Another explanation for the discrepancy in males’ views on responsibility and their sexual behaviors may be that “older” was not clearly defined by adolescents and is a relative term. Older males (say 18 or 19 years old) in our study may not identify themselves as such. Adolescents have shown characteristics of being older and more mature when they become parents (Perry & Pauletti, 2011), but further research is needed to identify other developmental transitions that make young men feel older, and to clarify what adolescents mean when they discuss the linkage between age and monogamy.

Limitations

The study's short-term goal was to contribute to the body of literature related to urban African American adolescent heterosexual relationship dynamics. We reached this goal using a qualitative approach to gather in-depth data that provided information on variation within the population. Even so, our work has limits. First, the interview responses that were examined came from adolescents who were recruited knowing they would be asked to discuss their personal and sexual life. Our findings suggest that the young men and women were open and honest about their sexual experiences and partner dynamics, but there is a possibility their answers were influenced by social desirability. Second, typical of qualitative research, findings may not be generalized to other populations, including African American adolescents living in other cities. Thus, future quantitative and qualitative research with similar populations should replicate and extend this work.

Although the study is not a comprehensive picture of adolescents’ romantic relationship dynamics, it gives a detailed snapshot of the context of their monogamy patterns. Therefore, the study can help inform prevention programs and future research on romantic relationships.

Future Directions and Prevention Implications

Our findings support previous research that has underscored the importance of considering gender-specific issues in the development of social-psychological STI/HIV prevention programs (e.g., Di Noia & Schinke, 2007; Dworkin et al., 2007, 2006; Logan et al., 2002). Although prior programs are efficacious, research has also found that African American sexually experienced adolescents are in need of more tailored and intensive interventions (e.g., Marshall, Crepaz, & O'Leary, 2010). Our results may contribute to the development of new programs by providing information on gender-related factors that affect adolescents’ commitment in relationships and by adding to our understanding of how commitment, trust, and respect relate to monogamous status differently for males and females. Given the focus of the current study was on heterosexual adolescents, future research may explore how gender-specific factors related to monogamy, trust, respect, and commitment revealed in the current data are enacted in same-sex romantic relationships.

Prior to this study, minimal research examined the association between commitment and mutual monogamy among African American adolescents. Other researchers have examined minority urban youths’ romantic relationship commitment, but their focus has been on commitment and condom use, and findings are contradictory. Some prior research has suggested that when two individuals are committed in a relationship, the likelihood that they will use condoms increases (Inazu, 1987; Manning et al., 2000). On the other hand, other work has found that commitment can increase trust levels in a relationship and decrease the likelihood of condom use (Riehman et al., 2006). Because research is mixed with regards to the impact commitment has on condom use, further related investigations are needed.

Specifically, future research should build on these former studies that examine commitment and condom use (Inazu, 1987; Manning et al., 2000; Riehman et al., 2006), and on the current study. Such research should examine how commitment, trust, respect, and monogamous status may affect adolescents’ condom use. Researchers have identified various perceived and actual barriers to African American adolescents’ condom use, including accessibility issues (Jones, Purcell, Singh, & Finer, 2005), embarrassment of buying condoms (MacDonald et al., 1990), perceived low risk of STI/HIV acquisition (Chapin, 2001; Murphy & Boggess, 1998), use of hormonal birth control and no condoms (Bauman & Berman, 2005), and trust in a partner (Bauman & Berman, 2005; Moore, Rosenthal, & Boldero, 1993). There is a gap in knowledge, however, regarding the gendered characteristics of heterosexual urban African American adolescents’ romantic relationship dynamics and how these dynamics affect adolescents’ use of condoms.

Furthermore, prevention programs may utilize our findings. Programs designed to address adolescent romantic commitment may build on existing interventions, such as those that focus on teaching sexual negotiation skills. Although STI/HIV behavioral intervention programs targeted at young African American women and that focus on teaching empowerment through self-efficacy, assertiveness, and negotiation skill building have demonstrated moderate efficacy (Crepaz et al., 2009), these programs may be enhanced if young women are also taught about the threat of committing to a noncommittal partner. Specifically, they can benefit from learning how to speak up for themselves and enhance safety (e.g., break up, use condoms) in noncommittal and nonexclusive relationships.

Our findings also have the potential to improve interventions involving young African American men. Although research consistently shows that African American adolescent males tend to engage in sex with multiple partners and be noncommittal, our findings point to contradictory gender role expectations when it comes to monogamous behaviors. Gender expectations that contradict multiple partnerships should be considered when designing prevention programs. Specifically, programs should challenge gender norms and teach males to follow through on their perceptions of being “responsible”, because related behaviors (e.g., monogamy) can act as protective factors against STI/HIV acquisition. Prior work has helped African American male youth challenge their attitudes toward women by coaching them to critically analyze media-based messages and images promoting negativity toward women (Watts, Abdul-Adil, & Pratt, 2002). Similar programs could be implemented to coach young African American males to challenge their attitudes and behaviors related to romantic relationship commitment and multiple partnerships. In addition, one avenue for teaching males how to follow through with protective behaviors is in their romantic relationships (e.g., communication, condom use) is to employ positive male mentors. Research has found that involving adolescents’ parents in prevention education curtails early onset sexual activity and can help to enhance intervention effects (DiClemente et al., 2007; Dilorio, McCarty, Resnicow, Lehr, & Denzmore, 2007; Johnson et al., 2011). Urban African American males may not always have parents who play an active role in their life. But, other role models, including uncles, friends, cousins, teachers, community center leaders, and even pastors, may be helpful for teaching adolescent males how to negotiate condom use, communicate with sexual partners about their monogamy status, and engage in honest behavior.

The findings from this study explain the interrelationship between relationship dynamics as the dynamics may influence sexual health (i.e., the impact commitment, trust, and respect have on monogamous behaviors) but did not examine how these dynamics may act as antecedents to African American adolescents’ condom use. Public health researchers may use this research to guide future studies that elaborate on these findings by continuing to explore the complex nature of romantic relationships and their impact on sexual health behaviors, specifically condom use. Public health practitioners may use the findings from this study as a guide to develop innovative prevention programs that consider young men and women's relationship dynamics.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Dr. Joseph Catania for his contributions to the overall project, and Lauren Fontanarosa for her contributions to the data analysis.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by an award from the California HIV Prevention Research Program (CHRP) [PI: Dolcini, ID02-SF-079]; the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) [PI: Coates, P30-MH62246]; and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) [PI: Dolcini, R01-HD061027].

Footnotes

Portions of this work were presented at the American Public Health Association annual meeting in Denver, in 2010.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Anderson E. Sex codes and family life among poor inner-city youths. Annals of the American Academy of Political Social Science. 1989;501:59–79. doi:10.1177/0002716289501001004. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Streetwise: Race, class, and change in an urban community. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Code of the street: Decency, violence and the moral life of the inner city. Norton; New York, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga XB, Agnew CR. Being committed: Affective, cognitive, and conative components of relationship commitment. Personal and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27(9):1190–1203. doi:10.1177/0146167201279011. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BL. To have loved and lost: Adolescent romantic relationships and rejection. In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Romance and sex in adolescence and emerging adulthood: Risks and opportunities. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bauch C, Rand DA. A moment closure model for sexually transmitted disease transmission through a concurrent partnership network. Proceedings of the Royal Society, Biological sciences. 2000;267(1456):2019–2027. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1244. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman LJ, Berman R. Adolescent relationships and condom use: Trust, love and commitment. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9(2):211–222. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-3902-2. doi:10.1007/s10461-005-3902-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg BL. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. 6th ed. Pearson; Boston, MA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Betts LR, Rotenberg KJ. The early childhood generalized trust belief scale. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2009;25:175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Teti M, Massie JS, Patel A, Malebranche DJ, Tschann JM. “What does it take to be a man? What is a real man?”: Ideologies of masculinity and HIV sexual risk among Black heterosexual men. Culture, Health, & Sexuality. 2011;13(5):545–559. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.556201. doi:10.1080/13691058.2011.556201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buunk BP, Bakker AB. Commitment to the relationship, extradyadic sex, and AIDS preventive behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1997;27(14):1241–1257. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1997.tb01804.x. [Google Scholar]

- Canin L, Dolcini MM, Adler NE. Barriers to and facilitators of HIV-STD behavior change: Intrapersonal and relationship-based factors. Review of General Psychology. 1999;3(4):338–371. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.3.4.338. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, McLanahan S, England P. Union formation in fragile families. Demography. 2004;41(2):237–261. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0012. doi:10.1353/dem.2004.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2009. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2010. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/std.stats. [Google Scholar]

- Chapin J. It Won't Happen to Me: The Role of Optimistic Bian in African American Teens’ Risky Sexual Practice. The Howard Journal of Communication. 2001;12:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cook KS, editor. Trust in society. Vol. 2. Russell Sage; New York, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Marshall KJ, Aupont LW, Jacobs ED, Mizuno Y, Kay LS, O'Leary A. The efficacy of HIV/STI behavioral interventions for African American females in the United States: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(11):2069–2078. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139519. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.139519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Darbes L, Crepaz N, Lyles C, Kennedy G, Rutherford G. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk behaviors and incident sexually transmitted diseases in heterosexual African Americans. AIDS. 2008;22(10):1177–1194. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ff624e. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ff624e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Noia J, Schinke SP. Gender-specific HIV prevention with urban early-adolescent girls: Outcomes of the Keepin’ it Safe program. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2007;19(6):479–488. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.6.479. doi:10.1521/aeap.2007.19.6.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, Crosby RA. A review of STD/HIV prevention interventions for adolescents: Sustaining effects of using an ecological approach. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:888–906. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm056. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, Lang DL, Davies SL, Hook EW, 3rd, Robillard A. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: A randomized controlled trial. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(2):171–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.171. doi:10.1001/jama.292.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilorio C, McCarty F, Resnicow K, Lehr S, Denzmore P. Real men: A group-randomized trial of an HIV prevention intervention for adolescent boys. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(6):1084–1089. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.073411. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.073411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcini MM. Adolescent friendship networks and their relationship to sexual health in an urban African American neighborhood. The Bay Area Sexuality Research Group; San Francisco: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dolcini MM, Catania JA, Harper GW, Boyer CB, Richards KAM. Sexual health information networks: What are urban African American youth learning? Research in Human Development. 2012;9(1):54–77. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2012.654432. doi:10.1080/15427609.2012.654432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drumright LN, Gorbach PM, Holmes KK. Do people really know their sex partners? Concurrency, knowledge of partner behavior, and sexually transmitted infections within partnerships. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2004;31(7):437–442. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000129949.30114.37. doi:10.1097/01.OLQ.0000129949.30114.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Beckford ST, Ehrhardt AA. Sexual scripts of women: A longitudinal analysis of participants in a gender-specific HIV/STD prevention intervention. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;36(2):269–279. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9092-9. doi:10.1007/s10508-006-9092-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Exner T, Melendez R, Hoffman S, Ehrhardt AA. Revisiting “success”: Posttrial analysis of a gender-specific HIV/STD prevention intervention. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(1):41–51. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9023-0. doi:10.1007/s10461-005-9023-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eames KTD, Keeling MJ. Monogamous networks and the spread of sexually tranmitted diseases. Mathematical Biosciences. 2004;189:115–130. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler R, Hersen M, editors. Handbook of gender, culture, and health. Lawrence Eribaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Eyre SL, Auerswald C, Hoffman V, Millstein SG. Fidelity management: African American adolescents’ attempts to control the sexual behavior of partners. Journal of Health Psychology. 1998;3(3):393–406. doi: 10.1177/135910539800300308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Shaffer L. The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations: Theory, research, and practical implications. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF. The fading dream: Prospects for marriage in the inner city. In: Anderson E, Massey DS, editors. Problem of the century: Racial stratification in the United States. Russell Sage; New York, NY: 2001. pp. 247–246. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano P, Manning W, Longmore M. The romantic relaitonships of African American and white adolescents. The Sociological Quarterly. 2005;46(3):545–568. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2005.00026.x. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano P, Manning W, Longmore M. Adolescent romantic relationships: An emerging portrait of their nature and developmental significance. In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Romance and sex in adolescence and emerging adulthood: Risks and opportunities. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 127–150. [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Gannon C, Watson SE, Catania JA, Dolcini MM. The role of close friends in African-American adolescents’ dating and sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 2004;41(4):351–362. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552242. doi:10.1080/00224490409552242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Timmons A, Motley DN, Tyler DH, Catania JA, Boyer CB, Dolcini MM. “It takes a village:” Familial messages regarding dating among African American adolescents. Research in Human Development. 2012;9(1):29–53. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2012.654431. doi:10.1080/15427609.2012.654431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inazu JK. Partner involvement and contraceptive efficacy in premarital sexual relationships. Population and Environment. 1987;9(4):225–237. doi:10.1007/BF01258968. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LA, Huedo-Medina TB, Carey MP. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents: A meta-analysis of trials, 1985-2008. Archives of Pediatrics &Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165(1):77–84. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.251. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LA, Smoak ND, Lacroix JM, Anderson JR, Carey MP. Behavioral interventions for African Americans to reduce sexual risk of HIV: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;51(4):492–501. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a28121. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a28121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RK, Purcell A, Singh S, Finer LB. Adolescents’ reports of parental knowledge of adolescents’ use of sexual health services and their reactions to mandated parental notification for prescription contraception. Journal of American Medical Association. 2005;293(3):340–348. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.340. doi:10.1001/jama.293.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapungu CT, Baptiste D, Holmbeck G, McBride C, Robinson-Brown M, Sturdivant A, Paikoff R. Beyond the “Birds and the Bees”: Gender Differences in Sex-Related Communication Among Urban African-American Adolescents. Family Process. 2010;49(2):251–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01321.x. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SS, Borawski EA, Flocke SA, Keen KJ. The role of sequential and concurrent sexual relationships in the risk of sexually transmitted diseases among adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;32(4):296–305. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00710-3. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00710-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan D, Andrinopoulos K, Johnson R, Parham P, Thomas T, Ellen JM. Staying strong: Gender ideologies among African American adolescents and the implications for HIV/STI prevention. Journal of Sex Research. 2007;44:172–180. doi: 10.1080/00224490701263785. doi:10.1080/00224490701263785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz A. MAXQDA (Version 10) [Computer Software] VERBI, Gmbh; Berlin, Germany: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Larzelere RE, Huston TL. The dyadic trust scale: Toward understanding interpersonal trust in close relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1980;42(3):595–604. doi:10.2307/351903. [Google Scholar]

- Levant RF, Pollack WS, editors. A new psychology of men. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, Cole J, Leukefeld C. Women, sex, and HIV: Social and contextual factors, meta-analysis of published interventions, and implications for practice and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(6):851–885. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.851. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Gender and relationships: A developmental account. American Psychologist. 1990;45(4):513–520. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.4.513. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.45.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning W, Giordano P, Longmore M. Hooking up: The relationship contexts of “nonrelationship” sex. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2006;21(5):459–483. doi:10.1177/0743558406291692. [Google Scholar]

- Manning W, Longmore M, Giordano P. The relationship context of contraceptive use at first intercourse. Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;32(3):104–110. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2648158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall K, Crepaz N, O'Leary A. A systematic review of evidence-based behavioral interventions for African American youth at risk for HIV/STI infection, 1988-2007. African Americans and HIV/AIDS. 2010;3:151–180. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-78321-5_9. [Google Scholar]

- Marston C, King E. Factors that shape young people's sexual behaviour: A systematic review. The Lancet. 2006;368:1581–1554. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69662-1. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69662-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe MP. Desired and experienced levels of premarital affection and sexual intercourse during dating. Journal of Sex Research. 1987;23(1):23–33. doi:10.1080/00224498709551339. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald NE, Wells GA, Fisher WA, Warren WK, King MA, Doherty JA, Bowie WR. High-risk STD/HIV behavior among college students. JAMA. 1990;263(23):3155–3159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misovich SJ, Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Close relationships and elevated HIV risk behavior: Evidence and possible underlying psychological processes. Review of General Psychology. 1997;1(1):72–107. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.1.1.72. [Google Scholar]

- Moore SM, Rosenthal D, Boldero J. Predicting AIDS preventive behavior among adolescents. In: Terry DJ, Gallois C, McCamish M, editors. The Theory of Reasoned Action: Its Application to AIDS-preventive Behavior. Pergamon; London: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JJ, Boggess S. Increased condom use among teenage males, 1988-1995: The role of attitudes. Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30(6):276–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussweiler T, Forster J. The sex-aggression link: A perception-behavior dissociation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:507–520. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.79.4.507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Carlyle K, Cole C. Why communication is crucial: Meta-analysis of the relationship between safer sexual communication and condom use. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(4):365–390. doi: 10.1080/10810730600671862. doi:10.1080/10810730600671862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Perry DG, Pauletti RE. Gender and adolescent development. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(1):61–74. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00715.x. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkerton CJ, Abramson PR. Evaluating the risks: A Bernouli process model of HIV infection and risk reduction. Evaluation Review. 1993;17:504–528. doi:10.1177/0193841X9301700503. [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH. The myth of masculinity. MIT Press; Cambridge: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL, Ku LC. Masculinity ideology: Its impact on adolescent males’ heterosexual relationships. Journal of Social Issues. 1993;49(3):11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond K, Levant R. Clinical application of the gender role strain paradigm: Group treatment for adolescent boys. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59(11):1237–1245. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10214. doi:10.1002/jclp.10214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehman KS, Wechserg WM, Francis SA, Moore M, Morgan-Lopez A. Discordance in monogamy beliefs, sexual concurrency, and condom use among young adult substance-involved couples: Implications for risk of sexually transmitted infections. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33(11):677–682. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000218882.05426.ef. doi:10.1097/01.olq.0000218882.05426.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Buunk BP. Commitment processes in close relationship: An interdependence analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1993;10(2):175–204. doi:10.1177/026540759301000202. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez D, Fetterolf JC, Rudman LA. Eroticizing inequality in the United States: The consequences and determinants of traditional gender role adherence in intimate relationships. Journal of Sex Research. 2012;49(2-3):168–183. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.653699. doi:10.1080/00224499.2011.653699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]