Abstract

Objective. A previous longitudinal study in rural New Hampshire showed that community mental health center clients with co-occurring schizophrenia-spectrum and substance use disorders (SZ/SUD) improved steadily and substantially over 10 years. The current study examined 7 years of prospective clinical and functional outcomes among inner-city Connecticut (CT) community mental health center clients with SZ/SUD. Method. Participants were 150 adults with SZ/SUD, selected for high service needs, in 2 inner-city mental health centers in CT. Initially, all received integrated mental health and substance abuse treatments for at least the first 3 years as part of a clinical trial. Assessments at baseline and yearly over 7 years measured progress toward 6 target clinical and functional outcomes: absence of psychiatric symptoms, remission of substance abuse, independent housing, competitive employment, social contact with non-users of substances, and life satisfaction. Results. The CT SZ/SUD participants improved significantly on 5 of the 6 main outcomes: absence of psychiatric symptoms (45%–70%), remission of substance use disorders (8%–61%), independent housing (33%–47%), competitive employment (14%–28%), and life satisfaction (35%–53%). Only social contact with nonusers of substances was unimproved (14%–17%). Conclusions. Many urban community mental health center clients with SZ/SUD and access to integrated treatment improve significantly on clinical, vocational, residential, and life satisfaction outcomes over time, similar to clients with SZ/SUD in rural areas. Thus, the long-term course for people with SZ/SUD is variable but often quite positive.

Key words: schizophrenia, co-occurring substance disorders, long-term course

Introduction

Long-term studies of schizophrenia consistently show diverse outcomes, with some researchers emphasizing more positive outcomes than others, and all studies showing great variability among participants.1,2 Few of these studies have been conducted in the era of community treatment (ie, among people who lived with schizophrenia in community settings post-deinstitutionalization), a period during which recovery among people with schizophrenia has often been complicated by the prevalence of co-occurring substance use disorders. Cross-sectional research has demonstrated robustly that people with co-occurring schizophrenia and substance use disorders (SZ/SUD) tend to function poorly in many areas, including symptoms and relapses, medical problems, disrupted relationships with family and friends, housing loss and homelessness, unemployment, legal problems, and incarceration.3–5 Some longitudinal studies have also documented negative outcomes for people with SZ/SUD,6,7 but others have shown relatively positive outcomes,8–13 again always with variability.

In a previous longitudinal study of people with SZ/SUD in rural New Hampshire (the NH Dual Diagnosis Study), a majority of participants receiving integrated treatment (mental health and substance abuse interventions) demonstrated steady progress toward recovery across several clinical and functional domains over 10 years.10 The NH participants lived in rural areas, were predominantly white, relatively well educated, and predominantly abused alcohol rather than cocaine. Long-term recovery may be quite different among disadvantaged inner-city individuals with SZ/SUD who are abusing illicit drugs in addition to alcohol.

This paper reports on 7-year outcomes among people with SZ/SUD who received integrated treatment in community mental health centers in the most disadvantaged sections of 2 impoverished cities, Hartford and Bridgeport, Connecticut. The Connecticut (CT) Dual Diagnosis Study participants had similar schizophrenia spectrum disorders as the NH cohort, but much greater social disadvantage than their NH counterparts, including: minority status (71.7% vs 3.6%), level of education (50.0% vs 72.9% graduated from high school), recent homelessness (39.6% vs 26.9%), previous incarceration (58.8% vs 40.7%), and recent employment (27.9% vs 45.2%).9 Cocaine use disorder was the most common substance use disorder in CT (60.8% in CT vs 15.1% in NH), while alcohol use disorder was the most common in NH. Cocaine use may have contributed to social disadvantage in CT due to its illegal status and the related risk of criminal justice system involvement. The aims of the study were to assess the course of clinical and functional outcomes in the CT study. We hypothesized that the CT cohort would improve less than the NH cohort over these 7 years due to the relative social disadvantages.

Methods

Overview

The CT Dual Diagnosis study began as a randomized trial comparing 2 forms of case management (assertive community treatment versus standard clinical case management), each providing integrated treatment. The study enrolled 198 urban clients with severe and persistent mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder.14 Integrated treatment in the original study followed the dominant model at the time: multidisciplinary teams provided integrated mental health and substance abuse treatments, motivational interviewing, and dual recovery groups. The assertive community treatment teams had smaller caseloads and therefore greater capacity for providing intensive interventions. The standard case management teams had larger, individual caseloads and team-based supervision. Three-year results of the original trial showed that participants in both treatment arms improved on several dimensions with few differences between conditions. After the 3-year trial ended, participants and providers were released from experimental protocols, and participants continued to have access to integrated services. Consenting participants joined a naturalistic follow-up study for another 4 years. Given the lack of outcome differences in the main trial, we combined the 2 groups for the naturalistic follow-up.

Study Group

Participants in the initial trial met the following inclusion criteria: major psychotic disorder (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depression with psychotic features); active substance use disorder (abuse or dependence on alcohol or other drugs within the past 6 months); high service use in the past 2 years (2 or more of the following: psychiatric hospitalizations, stays in a psychiatric crisis or respite program, emergency department visits, or incarcerations); homelessness or unstable housing; poor independent living skills; no pending legal charges, life-threatening medical conditions, or mental retardation; being scheduled for discharge to community living if currently staying in an inpatient facility; and willingness to provide written informed consent. Of the original cohort, 150 were diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Participants with nonschizophrenia diagnoses were excluded for this report in order to employ the same eligibility criteria as the NH study.10

Procedures

Participants enrolled between August 1993 and July 1998. Clinician research interviewers gathered information at baseline and every 6 months for the first 3 years and annually thereafter. The institutional review boards of the CT Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, the Southwest CT Mental Health System, Dartmouth College, and the University of CT approved the protocol. Participants signed written informed consent at the beginning of the study and at the beginning of the naturalistic follow-up.

Measures

All measures were the same as those used in the parallel NH Dual Diagnosis Study.

Background Demographics and Diagnoses.

At baseline the research interview included items from the Uniform Client Data Inventory to assess demographic information.15 Clinician research interviewers established participants’ diagnoses of mental and substance use disorders by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R.16

Clinical Services.

The annual interviews included standardized questions regarding service use during the previous 2 weeks.17 Specifically, interviewers asked participants whether they used crisis services, outpatient individual treatment, outpatient group treatment, or other mental health services.

Clinical Outcomes.

The research interview included the Expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) to assess current psychiatric symptoms,18 the Time-Line Follow-Back to assess days of alcohol and drug use,19 and the medical, legal, and substance use sections from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI).20,21 Researchers used all available information to rate alcohol and drug use yearly for the full 7 years on 3 standardized rating scales: the Alcohol Use Scale (AUS), the Drug Use Scale (DUS), and the Substance Abuse Treatment Scale (SATS).22–24 During the first 3 years, clinicians as well as participants contributed to ratings; subsequently information came from participant interviews only.

The AUS and DUS identify disorder severity on a 5-point scale based on DSM-III-R criteria: (1) abstinence, (2) use without impairment, (3) abuse, (4) dependence, and (5) physiological dependence. Drug or alcohol use ratings of abstinence or use without impairment indicated that participants were in control of their alcohol or drug use. The SATS indicates progressive involvement in treatment and movement toward long-term remission from a substance use disorder. Based on an 8-point scale, SATS ratings of 1 or 2 indicate early and late stages of engagement in treatment (the individual still meets criteria for substance abuse or dependence and demonstrates no motivation to change), and ratings of 3 and 4 indicate early and late stages of persuasion or motivation (still active abuse or dependence). Ratings of 5 and 6 indicate early active treatment (active involvement in treatment and remission for one month or less) and late active treatment (active involvement and remission for one to 6 months) respectively. A rating of 7 indicates early relapse prevention (remission for at least 6 months), and a rating of 8 indicates late relapse prevention (remission for at least one year).

Functional Outcomes.

Functional outcomes included housing, social support, and competitive employment. Researchers asked participants to report where they had been living and for how many days they had been hospitalized, incarcerated, homeless, and living independently using the Time Line Follow Back calendar method.20 Researcher interviewers used the Quality of Life Interview (QOLI) to assess specifics of daily activities, employment, social contact, and family contact; and subjective satisfaction with housing, social relations, family relations, and leisure, based on 7-point scales ranging from 1 = terrible to 7 = delighted.25 Subscale scores are calculated as the mean of items. The Quality of Life Interview also includes a general life satisfaction measure that asks how the respondent feels about his or her life overall on the 7-point “terrible” to “delighted” scale.

Recovery Score.

Researchers and participants in recovery in the NH Dual Diagnosis study identified 6 dimensions of recovery that were important to them: remission of substance use disorder, psychiatric symptom relief, independent housing, social contact with a nonsubstance user, competitive work, and life satisfaction.10 Together with researchers, they established the following recovery benchmarks: (1) psychiatric symptom recovery: no BPRS subscale average > 3; (2) substance abuse recovery: SATS score > 5, indicating that the individual has actively attained remission for at least one month; (3) independent housing: > 80% of the client’s days were spent residing in his or her own housing (responsible for rent and housing decisions); (4) competitive employment: worked in an integrated work setting that paid at least minimum wage and was contracted to the individual directly rather than to a program or mental health agency, for at least 1 day in the past 6 months (1 day of competitive employment is a standard marker of success because obtaining a job is the major hurdle and first jobs usually last for several months);26 (5) social recovery: regular contact (at least weekly) with friends who were not substance users; and (6) general satisfaction with life: >5 on the 7-point QOLI global satisfaction rating. Following procedures previously established,10 we summed these recovery scores, based on a 0/1 dichotomy for each item, to yield a Recovery Score.

Data Analysis.

We characterized the study group with descriptive statistics and examined the course of change by computing the mean score of each outcome each year over the 7-year study period, modeling time effects with generalized estimating equation (GEE) methods using the STATA xtgee procedure.27 We also examined the same longitudinal plots using the subgroup of 85 participants with complete baseline and endpoint data. We examined the relationships between substance abuse treatment (SATS) and other target outcomes at 7 years with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes information on baseline characteristics of the 150 participants in the study group. Most were male, had never married, and had never completed a high school education. The most common diagnoses were schizophrenia (vs schizoaffective disorder), alcohol use disorder, cannabis use disorder, and cocaine use disorder. Participants who completed the 7-year follow-up did not differ statistically from noncompleters on any baseline demographic and clinical characteristics. During the long-term follow-up (4–7 years), 106 (70.7%) of the original study group completed at least 1 interview.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics for 150 Clients With Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder and Co-occurring Substance Use Disorder

| Variables | Complete Follow-up (N = 90) | Incomplete Follow-up (N = 60) | Total (N = 150) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/ Count | SD/% | Mean/ Count | SD/% | Test Statistic | P | Mean/ Count | SD/% | |

| Age (y)a | 37.1 | 6.5 | 36.1 | 9.1 | t(148) = .84 | .41 | 36.7 | 7.6 |

| Race | χ2 = 6.08 | .11 | ||||||

| White | 21 | 23% | 18 | 30% | 39 | 26% | ||

| Hispanic | 8 | 9% | 11 | 18% | 19 | 13% | ||

| Black-African American | 60 | 67% | 29 | 48% | 89 | 59% | ||

| Other | 1 | 1% | 2 | 3% | 3 | 2% | ||

| Sex (male) | 69 | 77% | 44 | 73% | χ2 = .22 | .64 | 113 | 75% |

| Marital (never married) | 71 | 79% | 44 | 73% | χ2 = .62 | .43 | 115 | 77% |

| Education (completed high school or higher) | 45 | 50% | 28 | 47% | χ2 = .16 | .69 | 73 | 48% |

| Diagnosis (schizophrenia) | 67 | 74% | 40 | 67% | χ2 = 1.07 | .30 | 107 | 71% |

| Substance Use Disorder | ||||||||

| Current Alcohol Use Disorder (present) | 51 | 57% | 37 | 62% | χ2 = .37 | .54 | 88 | 59% |

| Current Cannabis Use Disorder (present) | 40 | 44% | 22 | 37% | χ2 = .90 | .34 | 62 | 41% |

| Current Cocaine Use Disorder (present) | 56 | 62% | 36 | 60% | χ2 = .08 | .78 | 92 | 61% |

| Other Drug Use Disorder (present) | 9 | 10% | 9 | 15% | χ2 = .85 | .36 | 18 | 12% |

Note: arange = 20–59 y.

Service Use.

Table 2 summarizes findings on service use during the past 2 weeks. The proportions of participants using the main service categories did not change over 7 years, with a majority reporting that they continued to receive individual outpatient services and one-third to over one-half reporting that they continued to participate in outpatient group treatments.

Table 2.

Seven Years of Outpatient Service Use Outcomes for 150 Clients With Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder and Co-occurring Substance Use Disorder

| Variables | Baseline mean (SD)/count (%) N = 150 | 1 y mean (SD)/count (%) N = 133 | 2 y mean (SD)/count (%) N = 129 | 3 y mean (SD)/count (%) N = 131 | 4 y mean (SD)/count (%) N = 72 | 5 y mean (SD)/count (%) N = 70 | 6 y mean (SD)/count (%) N = 85 | 7 y mean (SD)/count (%) N = 90 | Time | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crisis assistance past 2wk (yes) | 26 | 18% | 19 | 15% | 12 | 10% | 13 | 11% | 5 | 7% | 5 | 7% | 10 | 12% | 10 | 11% | NS |

| Outpatient individual treatment past 2wk (yes) | 97 | 66% | 86 | 66% | 79 | 63% | 84 | 68% | 47 | 69% | 49 | 73% | 56 | 67% | 56 | 62% | NS |

| Outpatient group treatment past 2wk (yes) | 50 | 34% | 60 | 46% | 57 | 45% | 65 | 52% | 38 | 56% | 31 | 46% | 28 | 34% | 38 | 42% | NS |

| Other mental health treatment past 2wk (yes) | 10 | 7% | 22 | 17% | 13 | 10% | 16 | 13% | 3 | 4% | 1 | 1% | 7 | 8% | 2 | 2% | * |

*P < .01; NS = P > .01

Outcomes.

Table 3 shows the mean longitudinal outcomes over 7 years. Clinical outcomes showed marked improvements. Participants had significant decreases in total BPRS symptoms and all BPRS subscales. They also improved on the SATS and other substance use outcomes except the ASI alcohol composite. They were more likely to live independently, and conversely were less likely to be hospitalized or homeless. They were also more likely to become competitively employed. General life satisfaction improved significantly, and participants expressed greater satisfaction with specific areas of their lives. Average outcome trajectories varied: some improved during the first 3 years and maintained, some fluctuated, and others continued to improve over 7 years. Although neither social contacts with nonsubstance users nor other measures of social participation improved, participants expressed greater satisfaction with their social lives. Table 3 also shows that total Recovery Scores improved significantly over time. These findings were unchanged when we restricted the analyses to the 85 participants with complete baseline and final substance use ratings and when we included initial treatment group assignment in the GEE models.

Table 3.

Seven Years of Clinical and Functional Outcomes for 150 Clients With Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder and Co-occurring Substance Use Disorder

| Variables | Baseline mean (SD)/count (%) N = 150 | 1 Year mean (SD)/count (%) N = 133 | 2 Year mean (SD)/count (%) N = 129 | 3 Year mean (SD)/count (%) N = 131 | 4 Year mean (SD)/count (%) N = 72 | 5 Year mean (SD)/count (%) N = 70 | 6 Year mean (SD)/count (%) N = 85 | 7 Year mean (SD)/count (%) N = 90 | Time | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric symptoms | |||||||||||||||||

| BPRS—total scorea | 48.9 | 13.8 | 44.6 | 12.7 | 45.1 | 13.0 | 43.5 | 12.2 | 40.9 | 13.9 | 39.7 | 12.8 | 39.7 | 11.8 | 40.3 | 11.2 | * |

| BPRS—affect | 2.3 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 0.9 | * |

| BPRS—anergia | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 0.8 | * |

| BPRS—thought disorder | 2.5 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.2 | * |

| BPRS—disorganization | 1.9 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 0.6 | * |

| BPRS—activation | 1.7 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 0.5 | * |

| Substance abuse | |||||||||||||||||

| SATSa | 2.9 | 1.4 | 3.7 | 1.7 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 6.0 | 2.2 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 6.0 | 2.2 | * |

| Alcohol Use Scale | 2.8 | 1.1 | 2.6 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.0 | * |

| ASI alcohol composite | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | NS |

| Drug Use Scale | 3.1 | 1.4 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.3 | * |

| ASI drug composite | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | * |

| Full remission in past 6 mob | 16 | 11% | 26 | 20% | 41 | 32% | 42 | 34% | 36 | 57% | 38 | 61% | 45 | 57% | 52 | 61% | * |

| Abstinence past 6 mob | 4 | 3% | 13 | 10% | 17 | 13% | 18 | 15% | 21 | 33% | 27 | 44% | 31 | 39% | 35 | 41% | * |

| Living situation | |||||||||||||||||

| >80% Days independent living past y (yes)a | 50 | 33% | 49 | 35% | 58 | 42% | 57 | 42% | 47 | 48% | 44 | 45% | 51 | 49% | 48 | 47% | * |

| Hospital stay past y (yes) | 90 | 60% | 58 | 41% | 43 | 31% | 42 | 31% | 23 | 24% | 21 | 21% | 35 | 33% | 28 | 27% | * |

| Jail/prison past y (yes) | 39 | 27% | 24 | 17% | 34 | 24% | 30 | 22% | 22 | 23% | 19 | 19% | 24 | 23% | 10 | 10% | NS |

| Homeless past y (yes) | 42 | 29% | 18 | 13% | 11 | 8% | 6 | 4% | 1 | 1% | 4 | 4% | 3 | 3% | 6 | 6% | * |

| Functional status | |||||||||||||||||

| Competitive job past y (yes)a | 20 | 14% | 23 | 16% | 17 | 12% | 22 | 16% | 15 | 16% | 20 | 23% | 20 | 20% | 27 | 28% | * |

| Social contact with nonabusers (yes)a | 21 | 14% | 32 | 23% | 32 | 23% | 28 | 21% | 8 | 11% | 6 | 8% | 12 | 13% | 16 | 17% | NS |

| Daily activities (0–1) | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | NS |

| Social contact (1–5) | 2.5 | 1.0 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 1.0 | NS |

| Family contact (1–5) | 3.0 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 3.0 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 3.2 | 1.1 | NS |

| Quality of life (1–7) | |||||||||||||||||

| General life satisfactiona | 4.6 | 1.5 | 4.9 | 1.5 | 4.7 | 1.5 | 5.0 | 1.5 | 4.9 | 1.7 | 5.0 | 1.6 | 5.2 | 1.3 | 5.2 | 1.3 | * |

| Satisfaction with housing | 4.7 | 1.4 | 5.0 | 1.2 | 5.1 | 1.3 | 5.2 | 1.2 | 5.1 | 1.2 | 5.2 | 1.5 | 5.3 | 1.2 | 5.2 | 1.2 | * |

| Satisfaction with social relations | 4.8 | 1.2 | 4.7 | 1.3 | 4.9 | 1.1 | 4.8 | 1.2 | 4.9 | 1.0 | 4.9 | 1.2 | 5.1 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | * |

| Satisfaction with family relations | 4.4 | 1.7 | 4.5 | 1.6 | 4.7 | 1.5 | 4.9 | 1.4 | 4.8 | 1.5 | 5.0 | 1.4 | 5.1 | 1.4 | 5.1 | 1.5 | * |

| Satisfaction with leisure | 4.6 | 1.2 | 4.7 | 1.1 | 4.8 | 1.3 | 4.8 | 1.2 | 4.9 | 1.3 | 4.7 | 1.4 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.1 | 1.1 | * |

| Recovery score | |||||||||||||||||

| Recovery score | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 1.4 | * |

ASI, Alcohol Severity Index; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; QOLI, Quality of Life Inventory; SATS, Substance Abuse Treatment Scale. N varies due to missing responses within interviews.

aitem with appropriate cutoffs used to determine recovery scores.

bdrug and alcohol.

*P < .01; NS = P > 01.

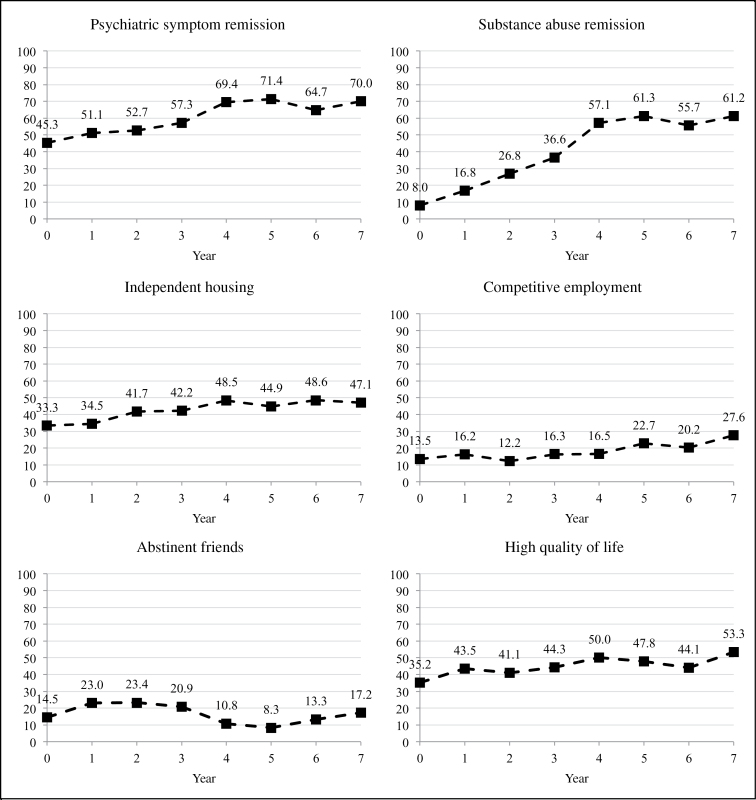

On the 6 recovery outcomes, participants improved on symptoms, substance abuse, employment, independent living, and life satisfaction, but not on social function. Figure 1 shows the trajectory of improvement on the 6 main recovery outcomes, plotting fitted means (covariance pattern models) and showing improvement for all variables except social function with similar slopes during the first 3 years of a controlled trial and the subsequent 4 years of naturalistic follow-up.

Fig. 1.

Percentage over Recovery Threshold by year for 6 Recovery Outcomes.

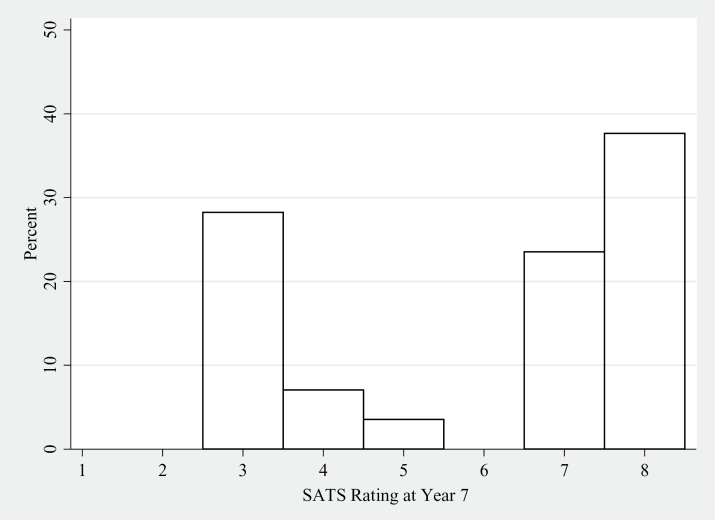

All target outcomes showed variability, as indicated by the large standard deviations in table 3. For example, figure 2 shows the spread of SATS scores at year 7. One large group remained in persuasion stages, while another large group attained relapse prevention stages, indicating substantial remissions. Relationships between the target outcomes were weak. For example, substance abuse treatment scale scores correlated weakly with social contact with nonabusers at (Spearman’s rho = 0.21, P = .06), and correlations between substance abuse treatment scale scores and other target outcomes were nonsignificant.

Fig. 2.

Substance Abuse Treatment Scale (SATS) Scores at Year 7 for 90 Participants. 1–2 = Early and Late Engagement; 3–4 = Early and Late Persuasion; 5–6 = Early and Late Active Treatment; and 7–8 = Early and Late Relapse Prevention.

Comparisons With NH Cohort.

Improvements over 7 years in the CT cohort were remarkably similar to those in the comparator NH cohort.10 For example, in CT the total symptom score on BPRS decreased from 48.9 at baseline to 40.3 after 7 years, while in NH the comparable decrease was from 47.9 to 38.8. Substance use disorder recovery scores in CT on SATS went from 2.9 to 6.0, while in NH the comparable scores were 2.9 to 5.7. Other measures of symptoms and substance use also improved in both studies. Rates of any competitive employment increased from 14% to 28% in CT, and from 6% to 24% in NH. General life satisfaction increased from 4.6 to 5.2 in CT, and from 4.1 to 4.6 in NH. Other measures of life satisfaction also improved in both studies. Social contacts with nonusers, however, increased only from 14% to 17% in CT, while the rate increased from 7% to 46% in NH. Other social contact variables also showed significant increases in NH but not in CT (table 3).

Discussion

Overall, clients with SZ/SUD who had entered treatment in inner-city community mental health centers in CT improved substantially over 7 years (3 years of participating in a controlled trial and 4 years of naturalistic follow-up) on clinical and some functional outcome measures. Their symptoms, living situations, employment, life satisfaction, and many other outcomes also improved. Nevertheless, outcomes varied considerably, illustrated by the dichotomy of substance abuse recovery, with 1 large group remaining in persuasion stages and a second large group in relapse prevention stages. Although measures of social functioning did not improve, clients’ perceived quality of social life did. Contrary to our study hypothesis, most of these changes were quite similar to results in the comparator rural study.10

How do we understand the similar results in such different contexts? We considered 3 possible explanations: First, because the 2 trials recruited participants who were deemed in need of services due to active substance abuse and problems living independently, the expected fluctuating course of disorders may have produced relatively positive outcomes (recruitment bias, or clinical regression to the mean). Second, integrated treatments may have been effective across outcomes, regardless of the case management format (treatment effectiveness). Third, the natural course for people with SZ/SUD who present for services may have tended toward improvements and recovery (temporal changes).

People recruited for trials of high-intensity interventions are usually having difficulties, and some initial improvements may be due to fluctuations of illness. Improvements of the magnitude seen due to recruitment bias seem unlikely in these studies, however, because participants were recruited largely from outpatient clinics and, overall, showed continued improvements over many years. The remaining 2 interpretations—treatment effectiveness and temporal changes—cannot be clearly separated because they were confounded, given what these trials were intended to test (assertive community treatment vs high-quality case management).

Positive treatment effects appear to be a plausible explanation because in both studies participants in the experimental and comparison conditions received integrated treatments that were considered state-of-the-art at the time. Participants in several other dual diagnosis treatment studies using different models of care have improved in similar ways.8,9,12,13,28–30 But another cohort of participants with primary psychosis and comorbid substance use followed naturalistically in New York City improved steadily over 2 years, despite minimal use of integrated treatments and with relatively little treatment of any kind other than medications.11 Further, research on integrated treatments has yielded mixed results.31 Therefore, we cannot rule out temporal changes as a plausible contributor to recovery outcomes. Long-term studies of people with substance use disorders have consistently shown that the natural history, even among those who receive no treatments, tends toward recovery.32 For people with substance use disorders, the goal of treatment may be to enhance different paths to recovery rather than to provide a single path.

Why can improvement surprise? Many in the field may have mistakenly inferred that the long-term course of people with SZ/SUD is extremely negative because cross-sectional studies often show poor adjustment. As a counterpoise, however, many researchers have pointed out that people with SZ/SUD tend to have better social functioning, less severe negative or deficit symptoms, and less severe cognitive impairment than people with schizophrenia who do not use alcohol and drugs.5,6,33,34 Heavy use of alcohol and other drugs may confound an accurate view of their psychotic illnesses. When people with SZ/SUD become abstinent, they may experience more enduring remissions of psychoses and become less impaired. Further, people with SZ/SUD tend to use smaller amounts of alcohol and other drugs than patients in addiction settings and may therefore have less physiological addiction.35,36 The course of substance use disorder in the general population suggests that recovery is the most common outcome, particularly for people who have less severe forms of addiction.32 All of these factors suggest a relatively good prognosis for people with SZ/SUD. Treatment aims to speed recovery and reduce exposure to the adverse outcomes associated with active substance abuse or dependence; hence access to treatment remains an important public health goal.

Recovery has myriad definitions. Treatment professionals generally define recovery in terms of both clinical and social improvements.32 People with serious mental disorders emphasize highly personal goals, which often include independent living, social and vocational participation, and a sense of agency, or self-management, in relation to treatment and symptoms.37 The President’s New Freedom Commission identified living, learning, working, and participating fully in one’s community as indicators of recovery.38

A majority of participants (over 60%) in the CT study did achieve meaningful clinical recoveries. But how substantial were the social recoveries? Nearly half of the participants did not attain independent living, and sizeable minorities continued to be hospitalized and incarcerated. Only a small minority worked competitively. And several measures of social function showed no improvement. Yet the participants expressed higher satisfaction with their lives across several domains, perhaps due to the changes in clinical symptoms and associated sequelae. Thus, the overall picture of social recovery was mixed. The findings are hopeful but do not indicate that social recovery is normative.

The CT cohort did not improve on most social and activity measures, in contrast with the NH cohort, which improved on all of the same measures. We have considered several possible explanations, most related to the different opportunities and challenges in inner-city environments compared to rural environments, but the reasons for the differences in social outcomes remain unclear. Measuring social recovery is inherently difficult.

Several limitations deserve mention. Although the CT study was one of the longest observational studies of recovery outcomes among inner-city mental health center participants with SZ/SUD, generalizability may be limited. Participants who remained in the study for the naturalistic follow-up may have been more connected with treatment providers and more adherent with treatment than those who dropped out of the research. Thus, attrition bias may have had some impact, particularly on the service use findings. CT is a relatively wealthy state that invests heavily in its system of mental health and addiction services. Similar positive trends toward recovery may not appear in other states with less funding. Another limitation may be secular trends related to drugs of abuse. The CT study occurred during the era of heavy, inner-city cocaine use but before the subsequent waves of methamphetamine and opiate abuse. Specific drugs of abuse and trends in law enforcement vary over regions of the U.S. and over time. Treatment fidelity was not monitored after the first 3 years of follow-up, and service integration may have eroded. The relationships between treatment and recovery were not carefully assessed. Treatment for SZ/SUD has also evolved. The CT study focused on integrated treatments that were state-of-the-art at the time, but other treatments have greater empirical support and may lead to better outcomes.31

Conclusions

People with SZ/SUD who live in disadvantaged, inner-city environments and have accessed integrated treatments in community mental health centers may have a relatively favorable long-term prognosis, often achieving clinical and functional recoveries. In this study, over 60% of participants in CT passed meaningful thresholds for recovery on clinical measures of psychiatric symptoms and substance abuse, and substantial minorities experienced some degree of social recovery. Many also were able to live independently and reported improved quality of life. These findings have inherent value by promoting optimism among clients, family members, and clinicians.

Funding

US Public Health Services (R01-MH-52872); National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH-63463); National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01-AA-10265); National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA037202); Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (UD3-SM51560, UD3-SM51802, UD9-MH51958).

Acknowledgments

Rosemarie Wolfe for data management, Keith Miles and Melinda Fox Smith for consensus ratings. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Harding CM, Brooks GW, Ashikaga T, Strauss JS, Breier A. The Vermont longitudinal study of persons with severe mental illness, II: long-term outcome of subjects who retrospectively met DSM-III criteria for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:727–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Breier A, Schreiber JL, Dyer J, Pickar D. National Institute of Mental Health longitudinal study of chronic schizophrenia. Prognosis and predictors of outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dixon L. Dual diagnosis of substance abuse in schizophrenia: prevalence and impact on outcomes. Schizophr Res. 1999;35(suppl):S93–S100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kerfoot KE, Rosenheck RA, Petrakis IL, et al. ; CATIE Investigators. Substance use and schizophrenia: adverse correlates in the CATIE study sample. Schizophr Res. 2011;132:177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Levinson DF, et al. Prevalence of substance abuse in schizophrenia: demographic and clinical correlates. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16:31–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kirkpatrick B, Amador XF, Flaum M, et al. The deficit syndrome in the DSM-IV Field Trial: I. Alcohol and other drug abuse. Schizophr Res. 1996;20:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kozarić-Kovacić D, Folnegović-Smalc V, Folnegović Z, Maruĭć A. Influence of alcoholism on the prognosis of schizophrenic patients. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:622–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bartels SJ, Drake RE, Wallach MA. Long-term course of substance use disorders among patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:248–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Drake RE, Yovetich NA, Bebout RR, Harris M, McHugo GJ. Integrated treatment for dually diagnosed homeless adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Xie H, Fox M, Packard J, Helmstetter B. Ten-year recovery outcomes for clients with co-occurring schizophrenia and substance use disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:464–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Drake RE, Caton CL, Xie H, et al. A prospective 2-year study of emergency department patients with early-phase primary psychosis or substance-induced psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:742–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morse GA, Calsyn RJ, Dean Klinkenberg W, et al. Treating homeless clients with severe mental illness and substance use disorders: costs and outcomes. Community Ment Health J. 2006;42:377–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Noordsy DL. Treatment of alcoholism among schizophrenic outpatients: 4-year outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:328–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Essock SM, Mueser KT, Drake RE, et al. Comparison of ACT and standard case management for delivering integrated treatment for co-occurring disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tessler RC, Goldman HH. The Chronically Mentally Ill: Assessing Community Support Programs. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clark RE, Teague GB, Ricketts SK, et al. Measuring resource use in economic evaluations: determining the social costs of mental illness. J Ment Health Adm. 1994;21:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lukoff D, Liberman RP, Nuechterlein KH. Symptom monitoring in the rehabilitation of schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Bull. 1986;12:578–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, eds. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. New York: Springer; 1992:41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tsemberis S, McHugo G, Williams V, Hanrahan P, Stefancic A. Measuring homelessness and residential stability: the residential time-line follow-back inventory. J Community Psychol. 2007;35:29–42. [Google Scholar]

- 21. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O’Brien CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980;168:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Drake RE, Osher FC, Noordsy DL, Hurlbut SC, Teague GB, Beaudett MS. Diagnosis of alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16:57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Drake RE, Mueser KT, McHugo GJ. Clinician rating scales: Alcohol Use Scale (AUS), Drug Use Scale (DUS), and Substance Abuse Treatment Scale (SATS). In: Sederer LI, Dickey B, eds. Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996:113–116. [Google Scholar]

- 24. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Burton HL, Ackerson TH. A scale for assessing the stage of substance abuse treatment in persons with severe mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183:762–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lehman AF. A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Eval Program Plann. 1988;11:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bond GR, Campbell K, Drake RE. Standardizing measures in four domains of employment outcomes for individual placement and support. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:751–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12 [computer program]. Version. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barrowclough C, Haddock G, Wykes T, et al. Integrated motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural therapy for people with psychosis and comorbid substance misuse: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c6325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lehman AF, Herron JD, Schwartz RP, Myers CP. Rehabilitation for adults with severe mental illness and substance use disorders. A clinical trial. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181:86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burnam MA, Morton SC, McGlynn EA, et al. An experimental evaluation of residential and nonresidential treatment for dually diagnosed homeless adults. J Addict Dis. 1996;14:111–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Drake RE, O’Neal EL, Wallach MA. A systematic review of psychosocial research on psychosocial interventions for people with co-occurring severe mental and substance use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34:123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vaillant GE. The Natural History of Alcoholism Revisited. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Potvin S, Joyal CC, Pelletier J, Stip E. Contradictory cognitive capacities among substance-abusing patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2008;100:242–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Salyers MP, Mueser KT. Social functioning, psychopathology, and medication side effects in relation to substance use and abuse in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;48:109–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Corse SJ, Hirschinger NB, Zanis D. The use of the Addiction Severity Index with people with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 1995;19:9. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lehman AF, Myers CP, Corty E, Thompson JW. Prevalence and patterns of “dual diagnosis” among psychiatric inpatients. Compr Psychiatry. 1994;35:106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Drake RE, Whitley R. Recovery and severe mental illness: description and analysis. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59:236–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Final Report. DHHS Pub. No. SMA-03-3832. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2003. [Google Scholar]