Abstract

Background

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a prevalent and disabling paranasal sinus disease, with a likely multi-factorial etiology potentially including hazardous occupational and environmental exposures. We completed a systematic review of the occupational and environmental literature to evaluate the quality of evidence of the role that hazardous exposures might play in CRS.

Methods

We searched PubMed for studies of CRS and following exposure categories: occupation, employment, work, industry, air pollution, agriculture, farming, environment, chemicals, roadways, disaster, or traffic. We abstracted information from the final set of articles across six primary domains: study design; population; exposures evaluated; exposure assessment; CRS definition; and results.

Results

We identified 41 articles from 1080 manuscripts: 37 occupational risk papers, 1 environmental risk paper, and 3 papers studying both categories of exposures. None of the 41 studies used a CRS definition consistent with current diagnostic guidelines. Exposure assessment was generally dependent on self-report or binary measurements of exposure based on industry of employment. Only grain, dairy and swine operations among farmers were evaluated by more than one study using a common approach to defining CRS, but employment in these settings was not consistently associated with CRS. The multiple other exposures did not meet quality standards for reporting associations or were not evaluated by more than one study.

Conclusion

The current state of the literature allows us to make very few conclusions about the role of hazardous occupational or environmental exposures in CRS, leaving a critical knowledge gap regarding potentially modifiable risk factors for disease onset and progression.

Keywords: sinusitis, epidemiology, environmental health, occupational health, farming

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a prevalent and disabling condition of the paranasal sinuses. It affects approximately 31 million people in the United States and accounts for an estimated $8.6 billion in direct health care expenditures.1 CRS is reported to have a more negative impact on quality of life than other chronic conditions, such as congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and chronic back pain.2–4 The European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps (EPOS) defines the clinical definition of CRS using both subjective symptoms and objective evidence by endoscopy or sinus CT scan.5 Without objective evidence of inflammation, it is challenging to distinguish CRS from conditions with overlapping symptoms, such as allergic rhinitis or migraine. Furthermore, it is difficult to use symptoms alone to differentiate between CRS subtypes, such as CRS with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) and CRS without nasal polyps (CRSsNP).6

The requirement for expensive, invasive, or ionizing radiation-exposed tests for diagnosis has created a barrier to epidemiological research, as large-scale studies including sinus CT or endoscopy are generally not feasible. Subsequently, most CRS studies have been conducted in tertiary care settings, where objective evidence is readily available on only the most severe cases. However, this approach is not suitable for occupational and environmental epidemiology studies, which should be population-based, and include the full spectrum of disease.

While little is known about the natural history of CRS, its variation, and the factors that explain that variation, evidence suggests that CRS is a chronic relapsing and remitting condition, beginning with the transition from acute rhinosinusitis (ARS) or rhinitis to CRS.6 Once CRS is established, it can transition between different disease states, including exacerbated CRS and difficult-to-treat CRS.5,6 Environmental exposures are among the proposed causes of transition from acute sinus disease to CRS and among the suggested triggers for symptom exacerbation of CRS, as the nasal and paranasal mucosa is the first interface with inhaled toxins, toxicants, and pollutants.7,8 Furthermore, some of the proposed pathways to CRS, including inflammatory dysregulation, epithelial barrier dysfunction, and impaired innate immunity can be triggered by several of the traditional hazardous exposures encountered in the workplace or the general environment, including toxic or irritant chemicals, secondhand smoke (SHS), and particulates.8–11 Several of these exposures are also known to cause occupational asthma or to exacerbate pre-existing asthma, a disease thought to have some overlapping pathophysiology with CRS.12–15 While there have been systematic reviews of the association between SHS and CRS, there have been no prior efforts to summarize and understand the complex literature concerning the broader set of possibly important etiologies for CRS or its progression that are amenable to preventive intervention.8,16

We completed a systematic review of the occupational and environmental epidemiology literature to evaluate the quality of evidence about the role that hazardous exposures may play in the onset of CRS, the differentiation into the two important CRS phenotypes (i.e., with or without nasal polyps), and the transition to CRS exacerbation or difficult-to-treat stage of CRS as defined by EPOS.5 Identification of the specific phenotype and disease stage under study is useful, as prior authors have argued that when CRS is considered as a single entity, consistent genetic and environmental risk factors have not been consistently identified.17

METHODS

Search strategy

We performed a systematic literature search to identify all relevant studies of the associations between occupational and environmental exposures and CRS. We searched PubMed of the U.S. National Library of Medicine with no limits on search period and limited the language to English. We searched for all possible combinations of terms for our outcomes and exposures of interest, linked by “and.” We used the following terms for our outcome: “chronic rhinosinusitis,” “rhinosinusitis,” “sinusitis” or “nasal polyp.” For exposures we searched on the following: “occupation,” “employment,” “work,” “industry,” “air pollution,” “agriculture,” “farming,” “farm,” “environment,” “chemicals,” “roadways,” “disaster,” or “traffic.” In addition to the articles captured by the search criteria, we manually reviewed the references in these publications for additional publications not previously identified. Although SHS is considered an environmental exposure, we excluded this exposure from our review because of two recent literature reviews of SHS and CRS.8,16

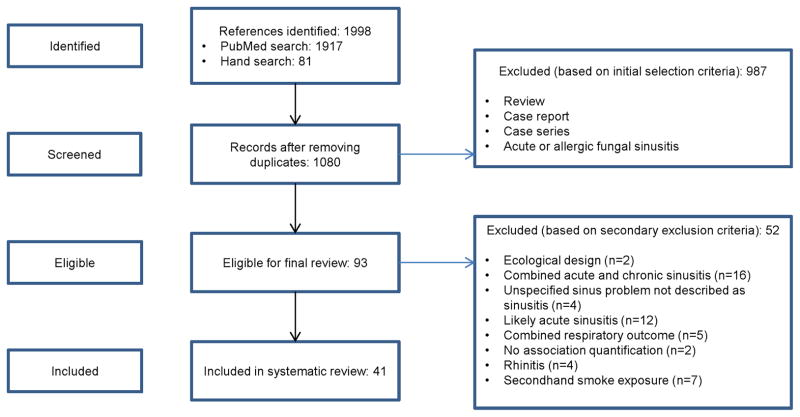

We first screened the articles for relevance by the title and abstract (Figure 1). We included articles if sinusitis and either an occupational or environmental exposure were mentioned in the title or abstract. We excluded publications that described a case report or case series or that were ecological in design. If the abstract did not provide sufficient details to conclude relevance to the review, we evaluated the full article. Next, we reviewed the full text of articles that met the initial eligibility criteria. If after reviewing the full article we determined that studies did not explicitly evaluate CRS, but studied another outcome (e.g., acute respiratory illness) we excluded the article. When eligibility of the article remained unclear after review, we contacted corresponding authors by e-mail for clarification. A single member of the study team identified the initial set of eligible articles using this selection criteria and two additional members of the team confirmed eligibility of the articles.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection process

Data extraction

We abstracted information from the final set of articles across six primary domains: study design (case-control, cohort, cross-sectional); study population (location, sample size, characteristics); exposures evaluated (environmental, occupational); exposure assessment and parameterization (e.g., exposure measurements vs. surrogates); CRS definition and stage in natural history (e.g., onset, exacerbation, difficult-to-treat); and results (associations of exposures with outcomes). All the disease stages and epidemiologic parameters under study were standard and previously defined in the literature.5 We also recorded the country in which the study was conducted, the time period of the study, and how confounding was addressed in analysis. Two authors abstracted the data elements independently and a third author adjudicated differences in the two abstractions.

We categorized the CRS outcome as CRS onset (incident disease), prevalent CRS, CRS exacerbation, or difficult-to-treat CRS, indicating the phenotype (e.g. CRSwNP, CRSsNP) when specified. We categorized the definitions used to determine CRS status into probable CRS, possible CRS, and least likely to be CRS. We classified a CRS definition as “probable” if the study used one of the following criteria to determine a CRS diagnosis: objective evidence of disease (sinus CT, nasal endoscopy, X-ray); diagnosis by an otolaryngologist (ENT) physician; or history of endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) for treatment of sinusitis. We classified a CRS definition as “possible” if the study used one of the following to define CRS: the EPOS CRS epidemiologic definition (i.e., compatible symptoms without objective test); 5 diagnosis from a physician (physician specialty not specified) based on a physical exam; or self-report of a physician diagnosis. CRS definitions that did not meet criteria for probable or possible CRS were classified as “least likely.”

Statistical analysis

As we found that there was very little between-study consistency in CRS definition, stage in natural history, exposure characterization, or associations evaluated, we did not perform any meta-analysis of reported associations across studies. We did not address publication bias using funnel plot as there were not enough studies with common methods to warrant the evaluation of publication bias.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

We identified 41 studies that met the final inclusion criteria. Of these studies, 37 articles evaluated only occupational risk factors, 1 only environmental, and 3 included both types of exposures (Table 1). Thirty-seven of these studies were of prevalent CRS. These papers did not specify whether the outcome was difficult-to-treat CRS or included the full spectrum of disease. There were no studies on CRS exacerbation. Of the three studies of disease onset, only one used a definition meeting probable CRS criteria.9,18,19 The most common study design identified, described in 19 of the papers, used a cross-sectional design that used a least likely CRS definition based on self-reported symptoms and measured exposure using an exposure surrogate of plant or job location. Only grain, dairy and swine operations among farmers were evaluated by more than one study using a possible or probable CRS definition. Self-reported hazardous work exposure was evaluated by 6 studies; however, each of the 6 studies assessed different exposures.9,20–24

Table 1.

Summary of included studies on CRS and environmental and occupational risk factors through May 2014

| Study characteristic | Frequency |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Risk factors studieda | |

|

| |

| Occupational | 40 |

|

| |

| Environmental | 4 |

|

| |

| Study design | |

|

| |

| Cross-sectional | 33 |

|

| |

| Case-control | 3 |

|

| |

| Cohort | 5 |

|

| |

| Sample size across studies | |

|

| |

| Mean ± standard deviation | 3551.5 ± 11317.8 |

|

| |

| Median | 216 |

|

| |

| Range | 48–59563 |

|

| |

| Continents where studies were conducted | |

|

| |

| Africa | 1 |

|

| |

| Asia | 4 |

|

| |

| Europeb | 29 |

|

| |

| North America | 7 |

|

| |

| CRS definition (see methods) | |

|

| |

| Probable CRS | 11 |

|

| |

| Possible CRS | 8 |

|

| |

| Least likely CRS | 22 |

|

| |

| CRS Phenotypes | |

|

| |

| CRSwNP | 6 |

|

| |

| CRSsNP | 0 |

|

| |

| CRS unspecified | 35 |

|

| |

| CRS natural history framework (stage of disease) | |

|

| |

| Onset | |

| Probable CRS | 1 |

| Least likely CRS | 2 |

|

| |

| Exacerbation | 0 |

|

| |

| Difficult-to-treat | |

| Probable CRS | 1 |

|

| |

| Prevalent (stage not specified) | 37 |

|

| |

| Number of studies that specifically report duration of symptoms | |

|

| |

| Probable CRSc | 0 |

|

| |

| Possible CRS | 5 |

|

| |

| Least likely CRS | 13 |

|

| |

| Summary of the studies | |

|

| |

| Cross-sectional, least likely CRS, exposure surrogate of plant or job location and self-reported symptoms | 19 |

|

| |

| Cross-sectional, at least possible CRS, exposure surrogate of job title | 11 |

|

| |

| Any design, any CRS category, self-reported occupational exposure or job title | 7 |

|

| |

| Cross-sectional, at least possible CRS, geographic proximity to exposure like industrial facilities or hog farms using geographic information systems | 2 |

|

| |

| Case-control, probable CRS, self-reported exposure to woodstove or air pollution | 2 |

Studies can be counted more than once;

20 of the 29 European studies were conducted in Yugoslavia/Croatia;

9 studies had an ENT diagnosis as the CRS criteria but did not mention duration, but it could be assumed that duration was considered in the diagnosis

CRS: chronic rhinosinusitis; CRSsNP: chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps; CRSwNP: chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps

Studies were published between 1964 and 2012 and were performed in 14 different countries. Half of the occupational risk studies (n=20) were conducted in Croatia or the former Yugoslavia and one study team, led by Zuskin and colleagues, conducted 19 of the 20 studies. Only 8 of the studies were primarily designed to study CRS. The remaining studies were designed to study respiratory or general health. All these studies were done on adults. No study used a CRS definition consistent with the EPOS clinical criteria. Thilsing et al. performed a population based study using a questionnaire containing the EPOS CRS symptom elements. This epidemiologic definition requires that two of four cardinal symptoms required for diagnosis of CRS be present for at least 12 weeks, but does not require objective evidence of inflammation.24

Approaches to CRS definition

There was heterogeneity in the definitions used for CRS across papers. Of the 41 papers, 11 met the probable CRS criteria, 8 met the possible criteria, and 22 met the least likely CRS criteria (Tables 2 and 4). Approximately 64% of the studies (N = 7/11) that met criteria for a CRS probable definition explicitly mention that they required objective evidence of inflammation via a CT or nasal endoscopy. Among the studies that met criteria for a CRS possible definition, four used a physician diagnosis and three used self-report of a physician diagnosis. The 22 papers we categorized as least likely CRS all depended on self-report of symptoms. In many cases the self-reported symptoms evaluated were not consistent with the EPOS definition for CRS. A number of studies classified individuals as CRS cases based on headache or facial pain symptoms, which in the absence of other nasal symptoms does not constitute CRS.25 While the EPOS definition for CRS requires sinus symptoms for at least three months, many studies did not specify duration of symptoms.5

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included OCCUPATIONAL Studies

| First author, Year Country Quality rankinga |

Study Design | Population | Data period |

Sample size | Exposure | CRS definition | CRS natural history studied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahman, 200128 Sweden PROBABLE CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: dairy, swine, and grain farmers Control: non-farmers |

1998 | Exposed: n=66 Control: n=19 |

Plant antigens: grain; animal dander: swine and cow | ENT diagnosed; endoscopy | Unspecified- prevalent CRSwNP |

| Casson, 199841 Italy PROBABLE CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: fishermen Control: male employees of the Local Health Authority |

NR | Exposed: n=139 Control: n=136 |

Fishing profession: fat soluble and persistent toxic contaminants, nitrous oxides and mineral oil spray, and adverse weather conditions | ENT diagnosed by local exam | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Collins, 200223 England PROBABLE CRS |

Cross-sectional | CRSwNP patients | 1991–1995; 1997 | Retrospective group: n=900 Prospective group: n=120 |

Dust and chemicals | ENT diagnosed | Unspecified- prevalent CRSwNP |

| Elbatawi, 196442 Egypt PROBABLE CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: workers in dusty card rooms in a cotton textile plant Control: unexposed workers from the same plant |

NR | Exposed: n=119 Control: n=84 |

Cotton dust inhalation | Physician exam; X ray | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Holmstrom, 200827 Sweden PROBABLE CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: dairy, swine, and grain farmers Control: office workers |

NR | Exposed: n=53 Control: n=15 |

Plant antigens: grain; animal dander: swine and cow | ENT diagnosed; endoscopy | Unspecified- prevalent CRSwNP |

| Hox, 201222 Belgium PROBABLE CRS |

Case–control | Case: FESS patients for recurrent ARS and CRS Control: vocal cord surgery patients |

2004–2008 | Case n=890 Control n=182 |

Bleach, inorganic dust, paints, cement, thinner, ammonia, white spirit, fuel gas, acetone | ENT diagnosis | Difficult-to-treat |

| Klingmann, 200743 Germany PROBABLE CRS |

Cohort | Injured divers | 2002–2005 | n=306 | Barotrauma: diving accidents | ENT diagnosis; sinus CT scan | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Rugina, 200226 France PROBABLE CRS |

Cohort | Bilateral CRSwNP patients | 1991–1996 | n=221 | Air pollutants | ENT diagnosed; endoscopy and CT | Unspecified- prevalent CRSwNP |

| Bener, 199844 United Arab Emirates POSSIBLE CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: garage mechanics Control: taxi drivers |

NR | Exposed n=158 Controls n=165 |

Motor vehicle exhaust emission | Physician diagnosis | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Bener, 199931 United Arab Emirates POSSIBLE CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: male farmers exposed to pesticides Control: male workers, not in farming or agriculture |

1997 | Exposed: n=98 Control: n=98 |

Pesticides: organophosphates and carbamate | Physician diagnosis | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Koh, 200945 Korea POSSIBLE CRS |

Cross-sectional | Civilian, non-institutionalized Korean adults aged 20–59 years | 1998, 2001, 2005 | 1998: n=20829 2001: n=20468 2005: n=18266 |

Gas, fumes, plant antigens | Self-reported physician diagnosis | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Thilsing, 201224 Denmark POSSIBLE CRS |

Cross-sectional | Danish residents: aged 20–75 years | 2008 | Men: n= 1200 Women: n=1331 |

Gases, fumes, dust, or smoke | EPOS epidemiologic definition | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Webber, 201146 US POSSIBLE CRS |

Cohort | World Trade Center (WTC) collapse responders | 2007–2009 | n=10943 | Caustic dust and toxic pollutants | Self-reported physician diagnoses | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 199347 Croatia POSSIBLE CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: male glass blowers Control: clerical office workers |

NR | Exposed: n=80 Control: n=80 |

Barotrauma: glass blowers | Physician diagnosis | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 199348 Croatia POSSIBLE CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: mustard and pickling workers Control: fruit juice bottling factory workers |

NR | Exposed: n=117 Control: n=65 |

Plant antigen: mustard seeds; vinegar, salt, various spices, natural flavoring, and turmeric | Physician diagnosis | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Al-Neaimi, 200149 United Arab Emirates LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: cement factory workers Control: Retail salesmen |

NR | Exposed: n=67 Control: n=134 |

Cement dust | Chronic sinusitis symptoms | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Herbert, 200619 US LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Cohort | WTC collapse responders | 2002–2004 | n=9442 | Caustic dust and toxic pollutants | Self-reported symptoms | Onset |

| Mustajbegovic, 200150 Croatia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: fulltime male firefighters Control: male food product packers |

NR | Exposed n=128 Control n=88 |

Caustic dust and toxic pollutants | Sinus pressure > 3 months AND/OR nasal dischargeb | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Webber, 200918 US LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Cohort | WTC collapse responders | 2001–2004 | n=10378 | Caustic dust and toxic pollutants | Self-reported symptoms | Onset |

| Wilson, 197351 US LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Cross-sectional | Exposed: civilian, non-institutional adults | 1970 | Households: n= 42,000 | Not specified (blue vs. white collar occupation) | Self-reported sinusitis | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 197952 Yugoslavia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: processors of roasted and green coffee Control: soft drink workers |

NR | Exposed: n=103 Control: n=103 |

Plant antigens: green and roasted coffee | Chronic sinusitis symptoms | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 198453 Yugoslavia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: female tea factory workers Control: soft drink workers |

NR | Exposed: n=100 Control: n=84 |

Plant antigens: dog-rose, sage, and chamomile, Indian, and gruzyan teas | Chronic sinusitis symptoms | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 198854 Yugoslavia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: female spice factory workers Control: female fruit juice bottling workers |

NR | Exposed: n=92 Control: n=104 |

Plant antigens: spices including hot paprika, sweet paprika, black pepper, parsley, garlic, onion, ginger, parsnip, turmeric, salt, and dextrose | Chronic sinusitis symptoms | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 198855 Yugoslavia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: furriers Control: fruit juice bottling workers |

NR | Exposed: n=40 Control: n=31 |

Animal fur: marten, domestic fox, polar fox, mink, Chinese lamb, domestic lamb, and Chinese calf | Chronic sinusitis symptoms | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 198856 Yugoslavia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: soybean workers Control: nonalcoholic beverage packers |

1982 | Exposed: n=27 Control: n=21 |

Plant antigens: soy | Chronic sinusitis symptoms | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 199057 Yugoslavia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: hemp factory workers Controls: packers in the food industry with no exposure to noxious dusts or fumes |

NR | Exposed: n=111 Control: n=79 |

Textiles: hemp used in the manufacturing of rope, fire hose, rugs, and clothing | Chronic sinusitis symptoms | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 199158 Yugoslavia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: male soybean workers Control: transport workers not exposed to industrial dust or fumes |

NR | Exposed: n=19 Control: n= 31 |

Plant antigens: soy | Chronic sinusitis symptoms | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 199459 Croatia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: confectionary workers Control: factory transport workers |

NR | Exposed: n=288 Control: n=96 |

Plant antigens: nuts, almonds, cocoa, cacao, chocolate, butter, honey, aromatic oil, fruits, flour, sugar, starch, talc, egg powder, and yeast; ethyl alcohol and food colorings | Chronic sinusitis symptoms | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 199560 Croatia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: wool textile workers Controls: delivery workers in plastic material plant |

NR | Exposed: n=216 Control: n=130 |

Textiles: wool | Sinus pressure > 3 months AND/OR nasal dischargeb | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 199661 Croatia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: female dried fruits and teas processors Controls: female transport workers |

NR | Exposed: n=54 Control: n=40 |

Plant antigens: fruits and teas including pineapple, orange, lemon, apple, peach, sage, dog rose, and chamomile | Chronic sinusitis symptoms | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 199862 Croatia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: male paper-recycling workers Control: food products packers |

NR | Exposed: n=101 Control: n=87 |

Paper dust, talc, chlorine gas, sulfur dioxide (SO2), chlorine dioxide, ammonia, and caustic soda | Sinus pressure > 3 months AND/OR nasal dischargeb | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 199863 Croatia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: synthetic fiber textile factory workers Control: unexposed workers from various industries |

1995 | Exposed: n=400 Control: n= 238 |

Textiles: polyester | Sinus pressure > 3 months AND/OR nasal dischargeb | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 199864 Croatia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: female cocoa and flour workers Control: female confectionary packers |

NR | Exposed: n=93 Control: n=65 |

Plant antigens: cocoa and flour | Chronic sinusitis symptoms | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 200065 Croatia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: male mail carriers Control: food industry packers |

1997 | Exposed n=136 Control n=87 |

SO2 and black smoke | Sinus pressure > 3 months AND/OR nasal dischargeb | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 200066 Croatia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: female workers exposed to the following:

Control: female unexposed workers |

NR | Exposed: n=764 Control: n=387 |

Plant antigens: green and roasted coffee, tea, spices, dried fruits, cocoa, and flour | Chronic sinusitis symptoms | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 200467 Croatia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: pharmaceutical manufacturers Control: employees at a food packing plant |

NR | Exposed: n=198 Control n=113 |

Pharmaceutical products: mainly antibiotics including Sumamed, Amoxyl, Klavocin, Ceporex, Novocef, and sulfonamides | Sinus pressure > 3 months AND/OR nasal dischargeb | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

| Zuskin, 200968 Croatia LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Industry-based cross-sectional | Exposed: male wind instrument musicians Control: male string instrument musicians |

NR | Exposed: n=99 Control: n=41 |

Barotrauma: wind musicians | Sinus pressure > 3 months AND/OR nasal dischargeb | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

CRS probable: objective evidence of disease (by sinus CT scan, nasal endoscopy, X-ray); diagnosis by an ENT physician; or history of endoscopic sinus surgery for treatment of sinusitis. CRS possible: EPOS CRS epidemiologic definition; diagnosis from a physician (ENT status not specified) based on a physical exam; or self-report of a physician diagnosis. Least likely CRS: CRS definitions that did not meet criteria for probable or possible CRS.

Definition confirmed by the author, Dr. Mustajbegovic by email on 4/1/2014 as “headache/facial pain or pressure of a dull, constant, or aching sort over the affected sinuses which lasts longer than three months. May be accompanied by thick nasal discharge that is usually green in color and may contain pus (purulent) and/or blood”

ARS: acute rhinosinusitis; CRS: chronic rhinosinusitis; CRSwNP: chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps; CT: computed tomography; ENT: Ear Nose Throat; EPOS: European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps; FESS: functional endoscopic sinus surgery; NR: not reported; SO2: sulfur dioxide; WTC: World Trade Center

Table 4.

Characteristics of Included ENVIRONMENTAL Studies

| First author, Year Country Quality rankinga |

Study Design | Population | Data period | Sample size | Exposure | CRS definition | CRS natural history studied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexiou, 201120b Greece PROBABLE CRS |

Cross-sectional | Case: CRSwNP patients admitted to otolaryngology department Control: orthopedic trauma patients |

2007–2009 | Case: n=100 Control: n=102 |

Dust, fumes, formaldehyde, chrome, nickel, arsenic, irritants, colors, solvents, and other volatile organic compounds | ENT diagnosis | Unspecified- prevalent CRSwNP |

| Kim, 200221b Canada PROBABLE CRS |

Matched case-control | Case: CRSwNP diagnosis Control: CRSsNP diagnosis |

1998 and 2001 | Case: n=55 Control: n=55 |

Woodstove, indoor tobacco smoke, pets, and occupational exposures to noxious inhalant compounds | ENT diagnosis; endoscopy | Unspecified- prevalent CRSwNP |

| Tammemagi, 20109b US PROBABLE CRS |

Matched case-control | Case: Nonsmoking incident CRS patients Control: Nonsmoking patients |

2000–2004 | Case: n=306 Control: n=306 |

Chemicals or respiratory irritants | ICD-9; CT or nasal endoscopy | Onset |

| Villeneuve, 200929 Canada POSSIBLE CRS |

Cross-sectional | Adults from rural communities in Ottawa | 2005–2006 | Adults: n= 723 | Animal dander: swine; smoking | Self-reported physician diagnosis | Unspecified- prevalent CRS |

CRS probable: objective evidence of disease (by sinus CT scan, nasal endoscopy, X-ray); diagnosis by an ear, nose and throat (ENT) physician; or history of endoscopic sinus surgery for treatment of sinusitis. CRS possible: EPOS (European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps) CRS epidemiologic definition; diagnosis from a physician (ENT status not specified) based on a physical exam; or self-report of a physician diagnosis. Least likely CRS: CRS definitions that did not meet criteria for probable or possible CRS.

Study has both occupational and environmental data

CRS: chronic rhinosinusitis; CRSwNP: chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps; CRSsNP: chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps; CT: computed tomography; ENT: Ear Nose Throat; ICD-9: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision

With few exceptions, the definitions used for CRS did not distinguish between phenotypes (CRSwNP and CRSsNP). Only 6 of the 41 studies focused on CRSwNP. 20,21,23,26–28 All 6 studies required an ENT diagnosis and 4 of the 6 studies also required objective evidence from an endoscopy to confirm the presence of nasal polyps. There were no studies that attempted to exclusively identify CRSsNP cases. The studies rarely distinguished among stages of disease. One study focused on difficult-to-treat CRS cases, defining these patients as having ENT confirmed CRS undergoing ESS who had persistent symptoms despite appropriate treatment.5,22 Three studies looked at onset of CRS, but two of the three studies used self-report of past and current symptoms to define onset of CRS.18,19 Tammemagi et al., in a study of air pollution and work exposure, used a definition for onset that met the possible CRS definition criteria, using medical record data to confirm the absence of CRS history and a combination of medical record data and CT or endoscopy to confirm case status.9

Approaches to exposure characterization

All of the studies identified used a surrogate measure (e.g., job role, job title, employer) or self-reported measure to assess exposure. The majority of the occupational studies (30 of 37) relied on employment at a facility (e.g., manufacturing plant) where the exposure of interest was suspected to be present. In nearly half of the occupational studies (17 of 40), workplace airborne exposure measurements were used to confirm the presence of the contaminant of interest. However, air quality and questionnaire data like duration of employment were rarely used to categorize exposure (e.g., high, medium, low) or create quantitative exposure gradients; rather, most studies used binary exposure groups (e.g., yes vs. no employed in industry) (Tables 3 and 5). Two studies used geographic information systems (GIS)-based approaches to ambient exposure characterization, generally by calculating the distance of residence to the source of environmental pollution like intensive hog farming, industries and dust-producing activities.20,29 The remaining studies used self-report to assess exposure (e.g., job roles, industry, exposures in home). Thilsing et al. used an asthma-specific job exposure matrix to create yes/no exposure variables for the different exposure categories like high molecular weight (HMW) chemicals, low molecular weight (LMW) chemicals, and mixed environment jobs, and Hox et al. used a similar classification.22,24

Table 3.

Exposure assessment, approach to confounding, exposure parameterization, and primary associations reported for eligible OCCUPATIONAL studies

| First author, Year Quality rankinga |

Exposure assessment | Approach to Confounding | Exposure Parameterization | Primary Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahman, 200128 PROBABLE CRS |

Mailed survey regarding the farm and work conditions | Not reported (NR) | Yes/no

|

Prevalence, % of farmers with polyps: Dairy farmer: 4 Swine farmers: 10 Grain farmers: 14 Control: 0 All comparisons vs. controls not significant (NS) |

| Casson, 199841 PROBABLE CRS |

Selected from deep sea fishing cooperatives. Survey: work duration, job, fishing in coastal/distant waters | Adjusted for cigarettes/day and chronic laryngitis | Yes/no: Job as a deck hand vs. employee of Local Health Authority (control) Yes/no: Job fishing in high sea vs. control |

Corresponding adjusted prevalence ratio (95% CI) of CRS:

|

| Collins, 200223 PROBABLE CRS |

Postal survey regarding occupational dust and chemical exposure: detailed report of occupational and recreational exposures and dates of exposure | NR | Yes/no: occupational exposure to dusts and chemicals | Prevalence, % (n) of occupational exposure: Retrospective group: 44.5 (400/900) Prospective group: 44.2 (53/120)c |

| Elbatawi, 196442 PROBABLE CRS |

Work in dusty card-rooms in cotton textile plant. Card-room air analysis using an electrostatic sampler to determine dust levels | Duration of work | Yes/no: work in dusty cardroom in cotton textile plant | Prevalence of chronic bacterial sinusitis: Exposed: 32.7% (39/119) vs. control: 14.3% (12/84) (p<0.01) |

| Holmstrom, 200827 PROBABLE CRS |

Questionnaire regarding farm work tasks and TWA dust values over a working day | Matched on sex and age | Yes/no

|

Prevalence, % (n) of nasal polyps: Dairy farmer: 5 (1/20) (NS) Swine farmer: 7 (1/15) (NS) Grain famer: 33 (6/18) (<0.05) Control: 0 (0/15) |

| Hox, 201222 PROBABLE CRS |

Mailed survey: occupational/recreational exposures, duration of exposures, type of agents. Reviewed and scored by occupational medicine physicians | Adjusted for asthma, current smoking state, presence of nasal polyps, and atopy | Yes/no to exposure to at least one of the following: HMW agents, LMW sensitizers, irritants | OR (95% CI) for occupational exposure yes vs. no: 2.45 (1.14–5.29) among patients with at least 1 FESS compared to those with no FESS |

| Klingmann, 200743 PROBABLE CRS |

Self-report to ENT: date of accident, number of dives, diving certification, history of acute diving accidents or follow up treatment, assessment of fitness to dive | NR | Average dives | Chronic sinusitis cases (33) had an average of 320 dives compared to 265 dives for those without chronic sinusitis (p < 0.05) |

| Rugina, 200226 PROBABLE CRS |

In-person survey: self-report exposure at work | NR | Yes/no: pollution at work Urban population vs. rural area residence |

No significant difference in natural history of NP by pollution at work or area of residence |

| Bener, 199844 POSSIBLE CRS |

Garage work job title/job location | Matched on age, sex, nationality, working hours, and duration of job | Yes/no: garage worker | Prevalence ratio of sinusitis: 1.33 (1.06–1.68) (p<0.03) |

| Bener, 199931 POSSIBLE CRS |

Farming job title/job location | Matched on age, sex, and nationality. Stratified by IgE level >180 IU/ml |

Yes/no: farmer | OR (95% CI) for sinusitis: 2.53 (0.99–6.47) |

| Koh, 200945 POSSIBLE CRS |

Interviewer-administered survey: occupational classification by: Korean Standard Classification of Occupations | Adjusted for age; stratified by sex | Yes/no

|

Prevalence ratio (95% CI) of exposed compared to clerical workers: (only significant associations listed) Elementary occupations: 1.68 (1.02–2.77) males (1998 wave) 3.07 (1.13–8.32) males (2001 wave) Plant/machine operators and assemblers: 2.88 (1.13–7.34) males (2001 wave) 1.76 (1.02–3.05) males (2005 wave) Unemployed: 1.81 (1.05–3.14) males (2005 wave) 2.07 (1.08–3.96) females (2005 wave) Craft and related trades workers: 1.73 (1.03–2.92) males (2005 wave) |

| Thilsing, 201224 POSSIBLE CRS |

Mailed survey. ISCO codes occupational exposure assessment and an asthma-specific JEM | Adjusted for smoking status, asthma, and nasal allergy. Stratified by sex |

|

Corresponding adjusted prevalence ratio (95% CI) for CRS:

|

| Webber, 201146 POSSIBLE CRS |

Fire Department of New York (FDNY) survey on world trade center (WTC) collapse responders: occupation, duty status, arrival group, and duration of exposure | NR | Exposure categories based on arrival at the WTC site:

|

Prevalence (%) of sinusitis:

|

| Zuskin, 199347 POSSIBLE CRS |

Physician administered survey: duration of employment in the glass-blowing industry | Stratified by duration in industry | Yes/no: glass blower | Prevalence, % (n) of chronic sinusitis: Exposed: 28.8 (43/80) vs. control: 3.8 (3/80) (p<0.001) |

| Zuskin, 199348 POSSIBLE CRS |

Occupational survey on the pickling and mustard producing factory workers | Stratified by duration in industry | Yes/no

|

Prevalence, % (n) of sinusitis among exposed vs. control Pickling: 33.3 (12/36) Packing: 18.9 (7/37) Mustard: 22.7 (10/44) Controls: 1.5 (1/65) All comparisons vs. controls p<0.01 Pickling workers exposed more than 1 year (45.5%) vs. 1 year or less (14.2%) p <0.01 |

| Al-Neaimi, 200149 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Interviewer-administered survey: use of personal protection equipment; work setting in cement factory; work role | Matched on age, nationality, and socioeconomic status (SES) | Yes/no: cement worker | Prevalence, % (n) of sinusitis: Exposed: 26.9 (18/67) vs. unexposed: 11.2 (15/134) (p<0.05) |

| Herbert, 200619 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Interviewer-administered survey: job role at job site of WTC collapse responders | NR | Exposure categories by arrival date for work at WTC site

|

Prevalence (crude), % (n) of new or worsened sinus related symptoms by exposure category: Group 1: 41.9 (785) Group 2: 36.9 (712) Group 3: 36.6 (1,020) Group 4: 37.0 (783) Group 5: 30.1 (200) (trend test p<0.001) |

| Mustajbegovic, 200150 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Survey: occupational history of firefighters | Stratified by smoking habit | Yes/no: firefighter | Prevalence, % (n) of sinusitis: Exposed: 32.8 (42/128) vs. control: 2.3 (2/88) (p<0.01) |

| Webber, 200918 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Self-administered survey: arrival time, duration of work on WTC site from September 2001 to July 2002 | NR | FDNY-WTC exposure intensity index, based on arrival at the WTC site:

|

OR (95% CI) for persistent rhinosinusitis among earliest arriving workers compared with all others: 1.3 (1.1–1.6). Test for trend by arrival group: p<0.0001 |

| Wilson, 197351 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Health Interview Survey: job title self-report stratified blue/white collar occupation | NR | Blue vs. white collar | Sinusitis prevalence (%): Blue collar: 12.9% White collar: 14.8% |

| Zuskin, 197952 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Occupational survey of coffee workers. Casella personal samplers (2-stage, stationary samplers with membrane filter preceded by horizontal elutriator for respirable fraction) were used to measure airborne dust as an 8hr time weighted average (TWA) | Stratified by sex. Matched on age, height, and smoking. |

Yes/no:

|

Prevalence, (%) of sinusitis: Exposed roasted coffee females: 25.2 vs. control: 3.9 (p<0.01) Exposed green coffee females: 22.5 vs. control: 3.2 (p<0.05) Exposed roasted coffee males: 23.8 vs. control: 9.5 (NS) |

| Zuskin, 198453 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Occupational survey of tea workers. Casella personal samplers (2-stage, stationary samplers with membrane filter preceded by horizontal elutriator for respirable fraction) were used to measure airborne dust as an 8hr TWA | NR | Yes/no

|

Prevalence, (%) of sinusitis in tea workers and controls: Dog-rose: 30.0 (p<0.05) Gruzyan: 10.7 Sage: 15.0 Indian: 6.3 Chamomile: 11.5 Controls: 4.7 |

| Zuskin, 198854 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Occupational survey of spice factory workers. Casella personal samplers (2-stage, stationary samplers with membrane filter preceded by horizontal elutriator for respirable fraction) were used to measure airborne dust as an 8hr TWA | Matched on sex, age, and smoking | Yes/no: spice factory worker | Prevalence, % of sinusitis: Exposed: 27.2 vs. control: 2.9 (p<0.01) |

| Zuskin, 198855 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Survey of furriers. Dust samples collected from the air of the workplaces. Sampling preformed using a membrane filter. Respirable fur fibers counted by phase-contrast optical microscopy. Dust particles were determined by counting respirable fraction and nonrespirable fraction | Matched on sex, age, smoking | Yes/no: furrier | Prevalence, % (n) of chronic sinusitis: Exposed: 30.0 (12/40) vs. control: 3.2 (1/31) (p<0.01) |

| Zuskin, 198856 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Occupational survey of soybean workers. Casella personal samplers (2-stage, stationary samplers with membrane filter preceded by horizontal elutriator for respirable fraction) were used to measure airborne dust as an 8hr TWA | Matched on town, sex, and age | Yes/no: employed in processing soy bean | Prevalence, % (n) of sinusitis: Exposed: 14.8 (4/27) vs. control: 9.8 (2/21) (NS) |

| Zuskin, 199057 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Occupational survey of hemp workers. Casella personal samplers (2-stage, stationary samplers with membrane filter preceded by horizontal elutriator for respirable fraction) were used to measure airborne dust as an 8hr TWA. 2 stage. Agar plates were used to measure bacterial flora in the work areas | Stratified for sex and site | Yes/no: hemp worker | Prevalence, % (n) of sinusitis: Females Mill A: 26.1 (12/46) vs. controls 6.1 (3/49) (p<0.01) Mill B: 50 (19/38) vs. controls 6.1 (3/49) (p<0.01) Males Mill A: 33.3 (9/27) vs. controls: 6.7 (2/30) (p<0.01) |

| Zuskin, 199158 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Occupational survey of soybean workers. Casella personal samplers (2-stage, stationary samplers with membrane filter preceded by horizontal elutriator for respirable fraction) were used to measure airborne dust as an 8hr TWA | Matched on sex, age, and smoking habit | Yes/no: employed in processing soy bean | Prevalence, % (n) of sinusitis: Exposed: 10.5 (2/19) vs. control: 6.5 (2/31) (NS) |

| Zuskin, 199459 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Occupational survey of confectionery workers. Airborne dust samples in the mill were collected with Hexhlet horizontal 2 stage samplers during the 8 hr. work shift. 20 dust samples were collected in the areas where workers were examined | Stratified by sex and exposure group | Yes/no:

|

Prevalence, % (n) of sinusitis by sex: Exposed women: 23.6 (61/259) vs. control women: 1.5 (1/65) (p<0.001) Exposed men: 24.1 (7/29) vs. control men: 0 (0/31) (p<0.001) Prevalence, % (n) of sinusitis by group/sex:

Control women: 1.5 (1/65) Control men: 0 (0/31) All comparisons vs. controls p<0.01 |

| Zuskin, 199560 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Occupational survey of wool textile workers. Airborne dust in mill was sampled with Hexhlet horizontal 2-stage samplers as 8-hr TWA (n=25 samples) in opening, carding, and spinning and weaving areas. At least 3 measurements were made at each location | Stratified by sex and smoking status | Yes/no: wool textile worker | Prevalence, % (n) of sinusitis: Exposed female: 43 (68/158) vs. controls: 3.4 (3/87) (p<0.01) Exposed male: 62.1 (36/58) vs. controls: 2.3 (1/43) (p<0.01) |

| Zuskin, 199661 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Occupational survey of dried fruits and teas processing workers. Casella personal samplers (2-stage, stationary samplers with membrane filter preceded by horizontal elutriator for respirable fraction) were used to measure airborne dust as an 8hr TWA. A total of 12 dust samples were collected | Stratified by result of skin prick test | Yes/no: employed in processing of dried fruits/teas | Prevalence, % (n) of sinusitis: Exposed: 14.8 (8/54) vs. control: 0 (0/40) (NS) |

| Zuskin, 199862 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Occupational survey of paper-recycling workers. Dust concentrations were measured by 2-stage Hexhlet apparatus as 8-hr TWA in two areas of the plant on five separate days | Stratified by skin prick test | Yes/no: employed in the paper recycling industry | Prevalence, % (n) of sinusitis: Exposed: 31.7 (32/101) vs. controls 2.3 (2/87) (p<0.01) |

| Zuskin, 199863 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Occupational survey of synthetic textile workers. Airborne dust in 2 textile synthetic fiber mills was sampled with Hexhlet horizontal 2-stage samplers as 8-hr TWA (n=23 samples). At least three measurements were made at each location | Stratified by sex, age, smoking status and duration of employment | Yes/no: employed in a synthetic textile plant | Prevalence, % (n) of sinusitis in females: Textile workers: 21.4 (66/308) vs. controls: 0.6 (1/160) (p<0.01) All other strata NS. |

| Zuskin, 199864 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Occupational survey of cocoa and flour processing workers. Dust concentrations were measured by a 2-stage Hexhlet apparatus as 8 hr TWA. 5 samples of dust were collected in the cocoa processing areas and six samples were collected in the flour processing area | NR | Yes/no:

|

Prevalence, % (n) of sinusitis: Cocoa: 20 (8/40) Flour: 16.9 (9/53) Control: 1.5 (1/65) Both comparisons vs. controls (p<0.01) |

| Zuskin, 200065 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Occupational history survey of mail carriers. Exposures of workers determined by analysis of atmospheric parameters over last 10 years using the temperature-wind-humidity (TWH) index and a review of sulfur dioxide and black smoke during past 10 years | Matched on sex, age, duration of job and smoking habits. Stratified by smoking |

Yes/no: mail carrier | Prevalence, % (n) of sinusitis: Exposed: 38.9 (53/136) vs. control: 2.3 (2/87) (p<0.01) |

| Zuskin, 200066 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Occupational survey of food processing industrial workers. Dust concentrations were measured by 2-stage Hexhlet apparatus as 8-hr TWA. At least 10 samples were collected for each industry | Matched on age, sex and smoking | Yes/no:

|

Prevalence, % of sinusitis by groups:

Controls: 0 |

| Zuskin, 200467 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Physician administered survey. Employment at pharmaceutical manufacturer plant | Stratified by sex | Yes/no: pharmaceuticals processor | Prevalence, % (n) of sinusitis: Females: exposed: 33.7 (55/163) vs. controls 0 (0/92) (p<0.01) Males: exposed: 20 (7/35) vs. controls 0 (0/21) (p<0.01) |

| Zuskin, 200968 LEAST LIKELY CRS |

Detailed occupational history survey of wind instrument musicians: working environment, playing technique, and length of time they have played | Matched on sex. Stratified by smoking habit |

|

Prevalence, % (n) of chronic sinusitis: Exposed, smoker: 27.8 (10/36) Exposed, nonsmoker: 19.0 (12/63) Control, smoker: 7.1 (1/14) Control, nonsmoker: 0 (0/27) p<0.01 prevalence of sinusitis in exposed compared to controls. Sinusitis symptoms in relation to length of employment among exposed OR: 1.011 (0.912–1.125) |

CRS probable: objective evidence of disease (by sinus CT scan, nasal endoscopy, X-ray); diagnosis by an ENT physician; or history of endoscopic sinus surgery for treatment of sinusitis. CRS possible: EPOS (European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps) CRS epidemiologic definition; diagnosis from a physician (ENT status not specified) based on a physical exam; or self-report of a physician diagnosis. Least likely CRS: CRS definitions that did not meet criteria for probable or possible CRS.

The upper limit of confidence interval seems to be an error because its value is lower than the prevalence ratio itself. This is likely to be 203.

Manuscript notes this percent to be 53%

CI: confidence interval; CRS: chronic rhinosinusitis; ENT: Ear Nose Throat; FDNY: Fire Department of New York; FESS: functional endoscopic sinus surgery; HMW: high-molecular weight; ISCO: International Standard Classification of Occupations; JEM: job exposure matrix; LMW: low-molecular weight; NP: nasal polyps; NR: not reported; NS: not significant; OR: Odds ratio; RR: relative risk; SES: socioeconomic status; TWA: time weighted average; TWH: temperature-wind-humidity; WTC: World Trade Center

Table 5.

Exposure assessment, approach to confounding, exposure parameterization, and primary associations reported for eligible ENVIRONMENTAL studies

| First author, Year Quality rankinga |

Exposure assessment | Approach to Confounding | Exposure Parameterization | Primary Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexiou, 201120b PROBABLE CRS |

Interviewer-administered survey: 3 independent experts classified environmental exposure as none, not certain, and evident based on participant-reported past/current address; distance of homes from pollutant activities (e.g., industry, traffic); use of wood stove in home. Same procedure was followed for occupational exposure | Adjusted for sex, smoking habits, allergy history and education (medium, high, and superior) | Environmental exposure and occupational exposures: none, uncertain or certain Duration of occupational exposure: none, minimal to short, or long term |

OR (95% CI) for prevalent NP:

|

| Kim, 200221b PROBABLE CRS |

Written survey: exposure to woodstoves, occupational exposures, indoor tobacco smoke, pets, and dust. Phone survey: duration and intensity of exposure to woodstoves | Adjusted for age, woodstove use, male sex, allergy, aspirin intolerance, occupational exposures, tobacco smoke, and pets | Yes/no to use/presence of exposure:

|

OR (95% CI) for NP:

|

| Tammemagi, 20109b PROBABLE CRS |

Phone survey: exposure to air pollution and chemicals or respiratory tract irritants at work, through hobbies, and from other sources | Matched on age, sex, and race | Yes/no:

|

Unadjusted OR (95% CI):

|

| Villeneuve, 200929 POSSIBLE CRS |

GIS to determine distance between home and intensive hog farm | Adjusted for age, sex, cigarette smoking, and household income | Distance from home to hog farm (adults):

|

OR (95% CI) for sinusitis in adults

|

CRS probable: objective evidence of disease (by sinus CT scan, nasal endoscopy, X-ray); diagnosis by an ear, nose and throat (ENT) physician; or history of endoscopic sinus surgery for treatment of sinusitis. CRS possible: EPOS (European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps) CRS epidemiologic definition; diagnosis from a physician (ENT status not specified) based on a physical exam; or self-report of a physician diagnosis. Least likely CRS: CRS definitions that did not meet criteria for probable or possible CRS.

Study has both occupational and environmental data

CI: confidence interval; CRS: chronic rhinosinusitis; OR: Odds ratio; NP: Nasal polyps

Study design and sample selection

There were 33 cross-sectional, 5 cohort, and 3 case-control studies with different approaches to confounding (Tables 3 and 5). Multivariate analysis, stratification, and modeling were used to address a range of confounders, most commonly age, gender, and smoking status. The cross-sectional studies generally included only a one-time assessment of symptoms and none of the cross-sectional studies confirmed the absence or presence of CRS prior to exposure. Four of the 5 cohort studies selected cohorts based on employment in the industry of interest while one followed a cohort of patients with CRSwNP. For the case control studies and the CRSwNP cohort study, cases were generally recruited from tertiary referral populations or from among patients with a history of ESS.

Reported associations

A meta-analysis could not be performed, so here we summarize associations with exposures that were studied using probable or possible CRS definitions and for which exposure characterization was similar in at least one other study (Tables 3 and 5). We could not assign levels of evidence across the body of studies using standard approaches because there were no exposures for which similar approaches to exposure and outcome assessment were reported on more than once.30 Instead, we graded the level of evidence at the individual study level using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine – Levels of Evidence scoring system.30 This system assigns levels of evidence from 1a (strongest) to 5 (weakest) based on the design of the study. Most of the studies we identified used a cross-sectional study design (80.5%), an approach that does not allow for causal inference and is not graded by the Oxford system. Of the eight remaining studies, five were cohort studies, categorized as level 2b, and the three were case-control studies, categorized as level 3b. Farmers were evaluated in three studies.27,28,31 However, one study did not mention the kind of farming that was done, so only two studies with clear and similar exposure descriptions were available for review.27,28 Both studies were occupation-based cross-sectional studies that compared farmers to working non-farmers and used an ENT diagnosis and endoscopy to confirm prevalent CRSwNP. Neither study found an association between dairy or swine farming and CRSwNP; associations with grain farming were inconsistent, with Holstrom et al. reporting an association and Ahmen et al. reporting no association. In other studies, there were multiple other evaluated exposures but none that were reported on by more than one study.

DISCUSSION

We conducted, to our knowledge, the first systematic review of the relationship between hazardous occupational and environmental exposures and CRS. Our focus on these occupational and environmental exposures was a departure from previous literature that used the term “environmental exposure” in a very loose sense, to include, for example, personal tobacco use, viruses, and bacteria, as triggers for disease onset or exacerbation. While we identified 41 studies on occupational and environmental hazardous exposures, the literature to date is insufficient to draw conclusions about the relationship between the exposures studied and CRS. Most of the studies used a cross-sectional design, which does not allow causal inferences. With the exception of exposures related to farming, no exposures were studied more than one time using a definition for CRS based on more than self-reported symptoms. Due to poorly ascertained exposures and outcomes; an inability to assess between-study findings because of a lack of similar, separate studies of exposures and outcomes; and the use of research methods vulnerable to bias, the role of hazardous occupational and environmental exposures in the onset, natural history, and phenotypic expression (i.e., with and without nasal polyps) of CRS has been, to date, insufficiently characterized. This is a missed opportunity as these are likely important and numerous potentially modifiable risk factors for CRS.

In general, it is challenging to make conclusions about occupational and environmental risk factors for CRS due to a number of limitations in the current literature. The majority of the studies we identified used self-reported symptoms to classify cases without documenting objective evidence of inflammation. This approach to disease definition is vulnerable to misclassification. In addition, we found that multiple studies used non-standard approaches to symptom characterization, such as those that required only facial pain to identify CRS cases, potentially mislabeling conditions with facial pain symptoms, such as migraine, as CRS. Studies have revealed poor correlation between symptoms and radiologic findings, reporting that only 20 to 36% of patients with symptoms of CRS have objective evidence of inflammation on sinus CT scan.32,33 This suggests that studies that relied on symptoms only likely included only a small minority of patients who actually had CRS according to current definitions. Alternatively, the majority of studies that required CT or endoscopy to confirm case status ascertained cases from tertiary care clinics, jeopardizing both internal and external validity because of the inclusion of only the most severe subset of individuals. A less costly and invasive method like a questionnaire based methodology that does not involve ionizing radiation to identify CRS in large-scale population studies is needed. This would greatly assist future efforts to evaluate the environmental epidemiology of CRS.

Studies most often used surrogate measures of exposure, including job task or role, job title, or employment in the industrial setting of interest. These methods of exposure assessment, particularly the self-reported measures, are subject to dependent measurement error and exposure misclassification. Very few studies attempted to evaluate exposure temporality, intensity, duration, and none evaluated latency. No studies attempted to rank study subjects along a continuous exposure gradient with quantitative measurements, thus not allowing evaluation of exposure-effect relations for disease risk or severity. No studies used internal dose measurements (e.g., cotinine for tobacco, chemical metabolites).

The majority of occupational exposure studies were cross-sectional studies conducted on individuals currently employed in the industry. This type of sample selection is vulnerable to healthy worker bias, a well-documented source of selection bias that occurs because healthier individuals are more likely to be selected for the workforce and remain in the workforce,34 as well as survivor bias, as individuals who might have developed symptoms after workplace exposures would consider leaving to seek employment in settings that did not cause illness. Generally, both of these sources of bias tend to result in associations closer to the null. While the majority of studies used a comparison group that was also in the workforce, the healthy worker effect can differ across occupations, and results could be biased in either direction depending on how the health of employees differs between industries.

Given the prevalence of CRS and the high degree of burden of the disease, there has been a disproportionately small amount of research dedicated to understanding this condition. The majority of the studies we identified were designed to study general health or respiratory health, rather than CRS (80%). As a result, few of the studies were attentive to the complexity of the condition, including its distinct phenotypes and different disease stages. Nearly all of the studies in our review failed to distinguish between phenotypes, collapsing them into a single outcome of sinusitis. While there is considerable symptom overlap between CRSwNP and CRSsNP, there are differences in respective inflammatory profiles, treatment outcomes, and potentially, etiology.5,35,36 Regarding symptom exacerbations, while there are known relationships between occupational and environmental hazards and asthma and COPD, we did not find any studies of the role these exposures play in CRS exacerbations.37,38 Similarly, just as early life exposures may be protective for asthma, no studies have explored the role of early life exposures in CRS.39,40 Finally, studies have generally focused on prevalent symptoms consistent with, but not specific for, CRS. The current literature thus offers few insights into the role of the workplace or general environment in disease onset, disease severity, or the transition from a less severe stage to a more difficult-to-treat stage of disease.

CONCLUSION

It is biologically plausible that environmental and occupational hazardous exposures could increase the risk of incident CRS, play a role in critical transition points in the natural history of the disease, affect the medical control of the disease, and influence the two primary types of disease expression, specifically CRSwNP and CRSsNP. However, the current scientific literature has not rigorously evaluated any of these issues. This leaves a critical knowledge gap regarding potentially modifiable risk factors for disease onset, progression, and subtypes.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: This publication was supported by the Chronic Rhinosinusitis Integrative Studies Program (CRISP) U19-AI106683 grant from NIAID. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAID.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CRS

chronic rhinosinusitis

- CRSsNP

chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps

- CRSwNP

chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps

- CT

computerized tomography

- ENT

ear, nose, throat

- EPOS

European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps

- ESS

endoscopic sinus surgery

- FESS

functional endoscopic sinus surgery

- FDNY

Fire Department of New York

- GIS

geographic information systems

- HMW

high-molecular weight

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision

- ISCO

International Standard Classification of Occupations

- JEM

job exposure matrix

- LMW

low molecular weight

- NR

not reported

- NS

not significant

- OR

odds ratio

- RR

relative risk

- SES

socioeconomic status

- TWA

time weighted average

- TWH

temperature-wind-humidity

- WTC

World Trade Center

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: None

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.Bhattacharyya N. Incremental health care utilization and expenditures for chronic rhinosinusitis in the United States. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120(7):423–427. doi: 10.1177/000348941112000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gliklich RE, Metson R. The health impact of chronic sinusitis in patients seeking otolaryngologic care. Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery. 1995;113(1):104–109. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989570152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macdonald KI, McNally JD, Massoud E. The health and resource utilization of Canadians with chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(1):184–189. doi: 10.1002/lary.20034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soler ZM, Wittenberg E, Schlosser RJ, et al. Health state utility values in patients undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(12):2672–2678. doi: 10.1002/lary.21847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2012. Rhinol Suppl. 2012;(23):1–298. 3 p preceding table of contents. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan BK, Kern RC, Schleimer RP, Schwartz BS. Chronic rhinosinusitis: the unrecognized epidemic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(11):1275–1277. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1500ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kern RC, Conley DB, Walsh W, et al. Perspectives on the etiology of chronic rhinosinusitis: an immune barrier hypothesis. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22(6):549–559. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reh DD, Higgins TS, Smith TL. Impact of tobacco smoke on chronic rhinosinusitis: a review of the literature. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2012;2(5):362–369. doi: 10.1002/alr.21054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tammemagi CM, Davis RM, Benninger MS, et al. Secondhand smoke as a potential cause of chronic rhinosinusitis: a case-control study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136(4):327–334. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diaz-Sanchez D, Garcia MP, Wang M, et al. Nasal challenge with diesel exhaust particles can induce sensitization to a neoallergen in the human mucosa. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104(6):1183–1188. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auerbach A, Hernandez ML. The effect of environmental oxidative stress on airway inflammation. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12(2):133–139. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32835113d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mapp CE, Boschetto P, Maestrelli P, Fabbri LM. Occupational asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(3):280–305. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200311-1575SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin DC, Chandra RK, Tan BK, et al. Association between severity of asthma and degree of chronic rhinosinusitis. American journal of rhinology & allergy. 2011;25(4):205–208. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seybt MW, McMains KC, Kountakis SE. The prevalence and effect of asthma on adults with chronic rhinosinusitis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2007;86(7):409–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slavin RG. The upper and lower airways: the epidemiological and pathophysiological connection. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2008;29(6):553–556. doi: 10.2500/aap.2008.29.3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hur K, Liang J, Lin SY. The role of secondhand smoke in sinusitis: a systematic review. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2014;4(1):22–28. doi: 10.1002/alr.21232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akdis CA, Bachert C, Cingi C, et al. Endotypes and phenotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis: a PRACTALL document of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(6):1479–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webber MP, Gustave J, Lee R, et al. Trends in respiratory symptoms of firefighters exposed to the world trade center disaster: 2001–2005. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(6):975–980. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herbert R, Moline J, Skloot G, et al. The World Trade Center disaster and the health of workers: five-year assessment of a unique medical screening program. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(12):1853–1858. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexiou A, Sourtzi P, Dimakopoulou K, et al. Nasal polyps: heredity, allergies, and environmental and occupational exposure. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;40(1):58–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J, Hanley JA. The role of woodstoves in the etiology of nasal polyposis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128(6):682–686. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.6.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hox V, Delrue S, Scheers H, et al. Negative impact of occupational exposure on surgical outcome in patients with rhinosinusitis. Allergy. 2012;67(4):560–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins MM, Pang YT, Loughran S, Wilson JA. Environmental risk factors and gender in nasal polyposis. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2002;27(5):314–317. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2002.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thilsing T, Rasmussen J, Lange B, et al. Chronic rhinosinusitis and occupational risk factors among 20- to 75-year-old Danes-A GA(2) LEN-based study. Am J Ind Med. 2012;55(11):1037–1043. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benninger MS, Ferguson BJ, Hadley JA, et al. Adult chronic rhinosinusitis: definitions, diagnosis, epidemiology, and pathophysiology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(3 Suppl):S1–32. doi: 10.1016/s0194-5998(03)01397-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rugina M, Serrano E, Klossek JM, et al. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of nasal polyposis in France; the ORLI group experience. Rhinology. 2002;40(2):75–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmstrom M, Thelin A, Kolmodin-Hedman B, Van Hage M. Nasal complaints and signs of disease in farmers--a methodological study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128(2):193–200. doi: 10.1080/00016480701477644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahman M, Holmstrom M, Kolmodin-Hedman B, Thelin A. Nasal symptoms and pathophysiology in farmers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2001;74(4):279–284. doi: 10.1007/pl00007944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villeneuve PJ, Ali A, Challacombe L, Hebert S. Intensive hog farming operations and self-reported health among nearby rural residents in Ottawa, Canada. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:330. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. [Accessed March 02, 2015];Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine – Levels of Evidence. 2009 Mar; http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/

- 31.Bener A, Lestringant GG, Beshwari MM, Pasha MA. Respiratory symptoms, skin disorders and serum IgE levels in farm workers. Allerg Immunol (Paris) 1999;31(2):52–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhattacharyya N, Lee LN. Evaluating the diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis based on clinical guidelines and endoscopy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143(1):147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhattacharyya N. Ambulatory sinus and nasal surgery in the United States: demographics and perioperative outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(3):635–638. doi: 10.1002/lary.20777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li CY, Sung FC. A review of the healthy worker effect in occupational epidemiology. Occup Med (Lond ) 1999;49(4):225–229. doi: 10.1093/occmed/49.4.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bachert C, Zhang N, van Zele T, Gevaert P. Chronic rhinosinusitis: from one disease to different phenotypes. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23 (Suppl 22):2–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2012.01318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huvenne W, van Bruaene N, Zhang N, et al. Chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyps: what is the difference? Current allergy and asthma reports. 2009;9(3):213–220. doi: 10.1007/s11882-009-0031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arbex MA, de Souza Conceicao GM, Cendon SP, et al. Urban air pollution and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-related emergency department visits. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(10):777–783. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.078360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delfino RJ. Epidemiologic evidence for asthma and exposure to air toxics: linkages between occupational, indoor, and community air pollution research. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110 (Suppl 4):573–589. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brunekreef B, Von Mutius E, Wong GK, et al. Early life exposure to farm animals and symptoms of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema: an ISAAC Phase Three Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(3):753–761. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishimura KK, Galanter JM, Roth LA, et al. Early-life air pollution and asthma risk in minority children. The GALA II and SAGE II studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(3):309–318. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0264OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Casson FF, Zucchero A, Boscolo Bariga A, et al. Work and chronic health effects among fishermen in Chioggia, Italy. G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 1998;20(2):68–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elbatawi MA, Effat H, Hussein M, Elseguini M. Cotton dust inhalation and upper respiratory tract disease. Internationales Archiv fur Gewerbepathologie und Gewerbehygiene. 1964;20:443–448. doi: 10.1007/BF00389863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klingmann C, Praetorius M, Baumann I, Plinkert PK. Otorhinolaryngologic disorders and diving accidents: an analysis of 306 divers. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264(10):1243–1251. doi: 10.1007/s00405-007-0353-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bener A, Galadari I, al-Mutawa JK, et al. Respiratory symptoms and lung function in garage workers and taxi drivers. The journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health. 1998;118(6):346–353. doi: 10.1177/146642409811800613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koh DH, Kim HR, Han SS. The relationship between chronic rhinosinusitis and occupation: the 1998, 2001, and 2005 Korea National health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES) Am J Ind Med. 2009;52(3):179–184. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Webber MP, Glaser MS, Weakley J, et al. Physician-diagnosed respiratory conditions and mental health symptoms 7–9 years following the World Trade Center disaster. Am J Ind Med. 2011;54(9):661–671. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zuskin E, Butkovic D, Schachter EN, Mustajbegovic J. Respiratory function in workers employed in the glassblowing industry. Am J Ind Med. 1993;23(6):835–844. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700230602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zuskin E, Mustajbegovic J, Schachter EN, Rienzi N. Respiratory symptoms and ventilatory capacity in workers in a vegetable pickling and mustard production facility. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1993;64(6):457–461. doi: 10.1007/BF00517953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Neaimi YI, Gomes J, Lloyd OL. Respiratory illnesses and ventilatory function among workers at a cement factory in a rapidly developing country. Occup Med (Lond ) 2001;51(6):367–373. doi: 10.1093/occmed/51.6.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mustajbegovic J, Zuskin E, Schachter EN, et al. Respiratory function in active firefighters. Am J Ind Med. 2001;40(1):55–62. doi: 10.1002/ajim.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson RW. Cigarette smoking, disability days and respiratory conditions. J Occup Med. 1973;15(3):236–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zuskin E, Valić F, Skurić Z. Respiratory function in coffee workers. Br J Ind Med. 1979;36(2):117–122. doi: 10.1136/oem.36.2.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zuskin E, Skurić Z. Respiratory function in tea workers. Br J Ind Med. 1984;41(1):88–93. doi: 10.1136/oem.41.1.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zuskin E, Skuric Z, Kanceljak B, et al. Respiratory findings in spice factory workers. Arch Environ Health. 1988;43(5):335–339. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1988.9934944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zuskin E, Skuric Z, Kanceljak B, et al. Respiratory symptoms and lung function in furriers. Am J Ind Med. 1988;14(2):187–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zuskin E, Skuric Z, Kanceljak B, et al. Respiratory symptoms and ventilatory capacity in soy bean workers. Am J Ind Med. 1988;14(2):157–165. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zuskin E, Kanceljak B, Pokrajac D, et al. Respiratory symptoms and lung function in hemp workers. Br J Ind Med. 1990;47(9):627–632. doi: 10.1136/oem.47.9.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zuskin E, Kanceljak B, Schachter EN, et al. Immunological and respiratory changes in soy bean workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1991;63(1):15–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00406192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zuskin E, Mustajbegovic J, Schachter EN, Kern J. Respiratory symptoms and ventilatory function in confectionery workers. Occup Environ Med. 1994;51(7):435–439. doi: 10.1136/oem.51.7.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zuskin E, Mustajbegovic J, Schachter EN, et al. Respiratory symptoms and lung function in wool textile workers. Am J Ind Med. 1995;27(6):845–857. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700270608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zuskin E, Kanceljak B, Schacter EN, Mustajbegovic J. Respiratory function and immunologic status in workers processing dried fruits and teas. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 1996;77(5):417–422. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63341-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zuskin E, Mustajbegovic J, Schachter EN, et al. Respiratory function and immunological status in paper-recycling workers. J Occup Environ Med. 1998;40(11):986–993. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199811000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zuskin E, Mustajbegovic J, Schachter EN, et al. Respiratory findings in synthetic textile workers. Am J Ind Med. 1998;33(3):263–273. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199803)33:3<263::aid-ajim8>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zuskin E, Kanceljak B, Schachter EN, et al. Respiratory function and immunological status in cocoa and flour processing workers. Am J Ind Med. 1998;33(1):24–32. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199801)33:1<24::aid-ajim4>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zuskin E, Mustajbegovic J, Schachter EN, et al. Respiratory findings in mail carriers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2000;73(2):136–143. doi: 10.1007/s004200050019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]