Abstract

Purpose

Intermolecular multiple quantum coherences (iMQCs) are a source of MR contrast with applications including temperature imaging, anisotropy mapping, and brown fat imaging. Because all applications are limited by SNR, this study develops a pulse sequence that detects iZQCs with improved SNR.

Methods

A previously developed pulse sequence that detects iMQCs (HOT) is modified with a multi-spin-echo spatial encoding scheme (MSE-HOT). MSE-HOT uses a series of refocusing pulses to generate a stack of images which are averaged in post-processing for higher SNR. MSE-HOT performance is quantified by measuring its temperature accuracy and precision during hyperthermia of ex vivo red bone marrow (RBM) samples.

Results

MSE-HOT yielded a three-fold improvement in temperature precision relative to previous pulse sequences. Sources of improved precision were 1) echo averaging and 2) suppression of J-coupling in the methylene protons of fat. MSE-HOT measured temperature change with an accuracy of 0.6 °C.

Conclusion

MSE-HOT improved the temperature accuracy and precision of HOT to a level that is sufficient for hyperthermia of bone marrow.

Keywords: Intermolecular multiple quantum coherence, temperature imaging, red bone marrow, Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill

Introduction

Intermolecular multiple quantum coherences (iMQCs) are a unique source of MR contrast that arise from long-range (10 µm–1000 µm) magnetic dipolar couplings between two or more spins [1–3]. iMQCs have found a variety of applications in biomedical research including temperature imaging [1,4], whole-body spectroscopy [5], brown adipose tissue (BAT) imaging [6,7], and susceptibility anisotropy imaging [8]. This study develops a specific type of iMQC for improved temperature imaging in red bone marrow (RBM): the intermolecular zero quantum coherence (iZQC) between a water and methylene proton (methylene-water iZQC). Methylene-water iZQCs correspond to the simultaneous flipping of a methylene and water proton in opposite directions. The fundamental advantage of iZQCs is that they evolve at the difference frequency between the two spins involved, resulting in removal of some inhomogeneous broadening and retention of the methylene-water resonance frequency difference [1,4]. In the case of temperature imaging of fatty tissues, the large temperature coefficient of the water is retained but the lines are sharper [1,4].

Almost all applications of iMQCs in biological systems are limited by the signal to noise ratio (SNR) of the iMQC signal. This report exploits multiple-spin-echo (MSE) spatial encoding to improve the SNR of iMQC sequences. MSE encoding of methylene-water iZQCs is not trivial because J-coupling of methylene protons substantially attenuates the fat signal [9,10], which is problematic because iZQCs are often indirectly detected on the methylene spins of fat. Fortunately, MSE pulse sequences are known to prevent signal loss due to methylene J-coupling [9,10], and it was therefore expected that an MSE pulse sequence would increase the iMQC signal intensity of lipid rich tissues such as RBM. Enhancement of lipid signal during MSE experiments is sometimes called the “bright fat phenomenon” in biomedical contexts. Another motivation for the MSE approach is that in tissues where iZQCs are most useful, T2* is short and inhomogeneous linewidths are on the order of 1 ppm. Compared to gradient echo or echo-planar schemes, spin echo-based schemes are much less susceptible to inhomogeneity and short T2*-related artifacts. However, MSE encoding of iMQCs is complicated by the need to detect multiple coherence pathways and retain information about the chemical shift of water, which is usually refocused by a spin echo. The MSE-HOT sequence simultaneously overcomes the difficulties associated with J-coupling, detection of multiple coherence pathways, and retention of chemical shift information.

This study implements and tests the MSE-HOT pulse sequence, which triples the temperature precision of single-spin-echo HOT (SSE-HOT) in RBM. Part of this precision enhancement is explained by experiments and spin dynamics simulations showing that the bright fat phenomenon causes up to an 80% increase in methylene signal intensity, which is exploited for improved temperature precision. The root mean squared error of MSE-HOT temperature change measurements was determined by comparing MSE-HOT measurements to fiberoptic temperature measurements, resulting in an accuracy of 0.6 °C.

Methods

Imaging console

All 7T images and spectra were acquired on a Bruker 30 cm bore small animal imager (BioSpec 70/30; Bruker BioSpin MRI GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany). The magnet was equipped with an imaging gradient coil system (400 mT/m) and a 1H transmit-receive coil. For all imaging and spectroscopy experiments, the magnetic field was shimmed using the Bruker standard shimming routine. All 1 T spectra were acquired on an Aspect (Shoham, Israel) small animal imaging system.

MSE-HOT pulse sequence

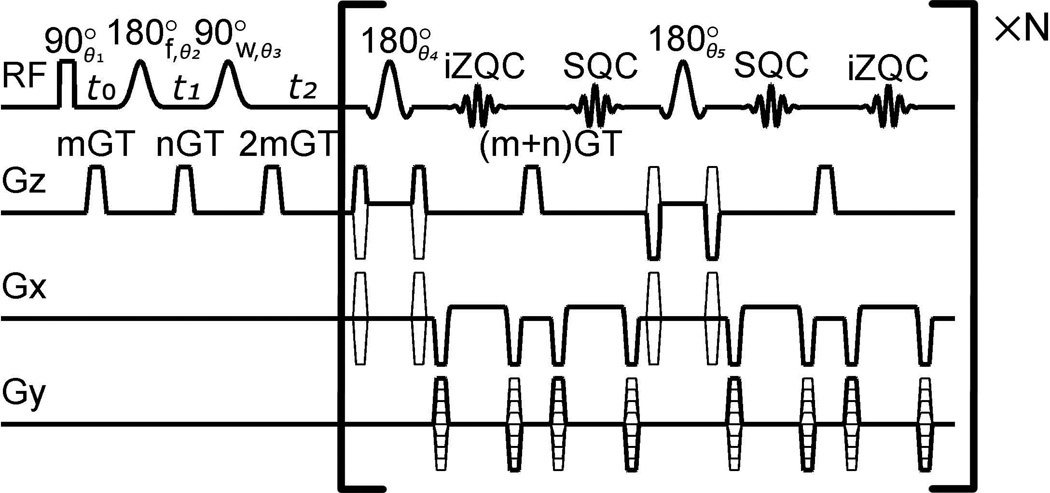

Figure 1 shows the MSE-HOT pulse sequence that was developed in this study. The portion outside the large brackets is the original SSE-HOT pulse sequence without a refocusing pulse [1,4]. The time between the four pulses in SSE-HOT is described by the variables t0, t1, t2. SSE-HOT generates one methylene-water iZQC echo and one methylene spin echo at times 2t2−2t1 and 2t2+t1−t0, respectively, after the 90°w pulse. In this study, t0 = 1.7 ms, t1 = 3.15 ms, t2 = 7.5 ms, m = −0.3, n = 0.7, GT = 5 mm−1. In time order, the pulses were a 0.1 ms rectangular pulse, a 2 ms Gaussian frequency selective pulse on methylene protons, a 3 ms Gaussian frequency selective pulse on water, and a 0.8 ms slice selective Hermite pulse on both methylene and water spins. Phase cycling parameters were θ1=x, −x, y, −y; θ2=θ4=θ5= y, y, y, y; θ3= x, x, x, x; iZQC acquisition phase: x, x, −x, −x; odd SQC echoes acquisition phase = x, −x, y, −y; even SQC echoes acquisition phase = x, −x, −y, y. Odd SQC echoes refer to the 1st, 3rd, 5th, etc. SQC echo. Odd and even SQC echoes have a different acquisition phase because they have been exposed to a different number of refocusing pulses.

Figure 1.

The MSE-HOT pulse sequence used for imaging RBM temperature.

K-space data were Fermi-filtered with the function

| (1) |

where Ex = Ey = 6 samples and Tx = Ty = 1 sample. K-space data were placed in a zero-filled 128×128 matrix and a two-dimensional inverse fast Fourier transform was applied to generate images. All image processing and reconstruction were performed using MATLAB R2014a (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, United States). All data and MATLAB code can be found online at https://github.com/ryanmdavis/MSE-HOT-thermometry.

The portion of the pulse sequence after the first refocusing pulse in the brackets is the MSE encoding scheme. This part of the pulse sequence applies a refocusing pulse then acquires both a SQC echo and water-methylene iZQC echo. All 180° pulses after the first 180° were Shinnar-Le Roux pulses with near uniform refocusing angle across the 1000 Hz separation between water and methylene protons. Spatial encoding gradients create an iZQC image zn(x,y) and an SQC image sn(x,y) where the subscript n references the echo number in the echo train. “x” and “y” refer to spatial coordinates. For example, the iZQC image after the second 180° in the brackets is z2(x,y). Note that the time order of zn(x,y) and sn(x,y) switch after each refocusing pulse. The time between slice selective refocusing pulses was 11.6 ms. Importantly, the refocusing pulses were surrounded by crusher gradients, but the direction of the gradient was different for different pulses. This prevented formation of unwanted echoes that could interfere with the iZQC signal. The direction of the crusher gradients followed the cyclic order +z, −z, +x, −x.

Calculation of phase difference images

Each pair of zn(x,y) and sn(x,y) were used to calculate a phase difference image dn(x,y) as described below. Since applying a refocusing pulse to the system during t2 (Figure 1) shifts the phase of the magnetization by 180° and then takes the complex conjugate of the iZQC in the complex plane, the following equations were used to calculate dn(x,y):

| (2a) |

| (2b) |

where ∠ extracts the angle of sn(x,y) in radians. ∠dn(x,y) is equal to the phase of the iZQC in the rotating frame, such that ∠dn(x,y)=(ω w−ωf)(t0+t1), where (ωw−ωf) is the temperature-dependent iZQC frequency [1,4].

iZQC signal vs time

In this study, the complex iZQC signal is characterized by measuring dn(x,y) with both the SSE-HOT and MSE-HOT pulse sequences. Three ex vivo porcine rib RBM samples were heated with 37 °C air for 1 hour before imaging. For measuring d1(x,y) as a function of echo time with SSE-HOT, the pulse sequence in Figure 1 was run eleven times for echo times (TE≡2t2−2t1) 17.3 ms, 21.3 ms, 26.3 ms, 36.3 ms, 46.3 ms, 56.3 ms, 66.3 ms, 86.3 ms, 106.3 ms, 126.3 ms, 146.3 ms. Only the first two images (z1(x,y) and s1(x,y)) were used in the SSE-HOT experiments. For the MSE-HOT experiments, the pulse sequence in Figure 1 was run once, with 20 refocusing pulses (N=10 in Figure 1). For the imaging parameters used in this study, this generated an iZQC image at TE values of 11.6 ms, 29.0 ms, 34.8 ms, 52.2 ms, 58.0 ms, 75.4 ms, 81.2 ms, 98.6 ms, 104.4 ms, 121.8 ms, 127.6 ms, 145.0 ms, 150.8 ms, 168.2 ms, 174.0 ms, 191.4 ms, 197.2 ms, 214.6 ms, 220.4 ms, 237.8 ms. To be clear, each TE value required a different scan for the SSE-HOT data, but all TE values were acquired in one scan for the MSE-HOT data. For both SSE-HOT and MSE-HOT data, dn(x,y) was calculated, and its phase and magnitude were used to determine the iZQC phase and magnitude in the rotating frame. SSE-HOT and MSE-HOT data were acquired on the same samples.

It was necessary to determine how the phase of dn(x,y) varied as a function of n. Three voxels from two marrow samples were chosen resulting in six 20-member vectors of dn(x,y). The six vectors were zero-order phased so that the phase of d4(x,y) = 0 rad. The average of the six phase vectors was determined for each value of n, resulting in a 20 member vector d̄n(x,y). For weighted echo averaging (described below), the phase of d̄n(x, y), was fit to a quadratic equation:

| (3) |

and the magnitude of d̄n(x,y) was fit to

| (4) |

where a, b, c, d, and T2, are constants determined by the fits.

Weighted echo averaging

When taking the weighted sum of dn(x,y), hereafter referred to as d(x,y), the individual echoes were weighted according to the Equation 3 and Equation 4:

| (5) |

where TE has been explicitly written as a function of echo number “n”. The complex phase term ensures that the echoes do not add destructively, which would decrease the SNR. The S̄ term weights each echo based on its relative signal intensity. The same S̄(TE) and φ̄(TE) curves were used for all voxels in all samples. Once the complex-valued d(x,y) images are calculated, the process for calculating temperature followed the process described in ref. [4].

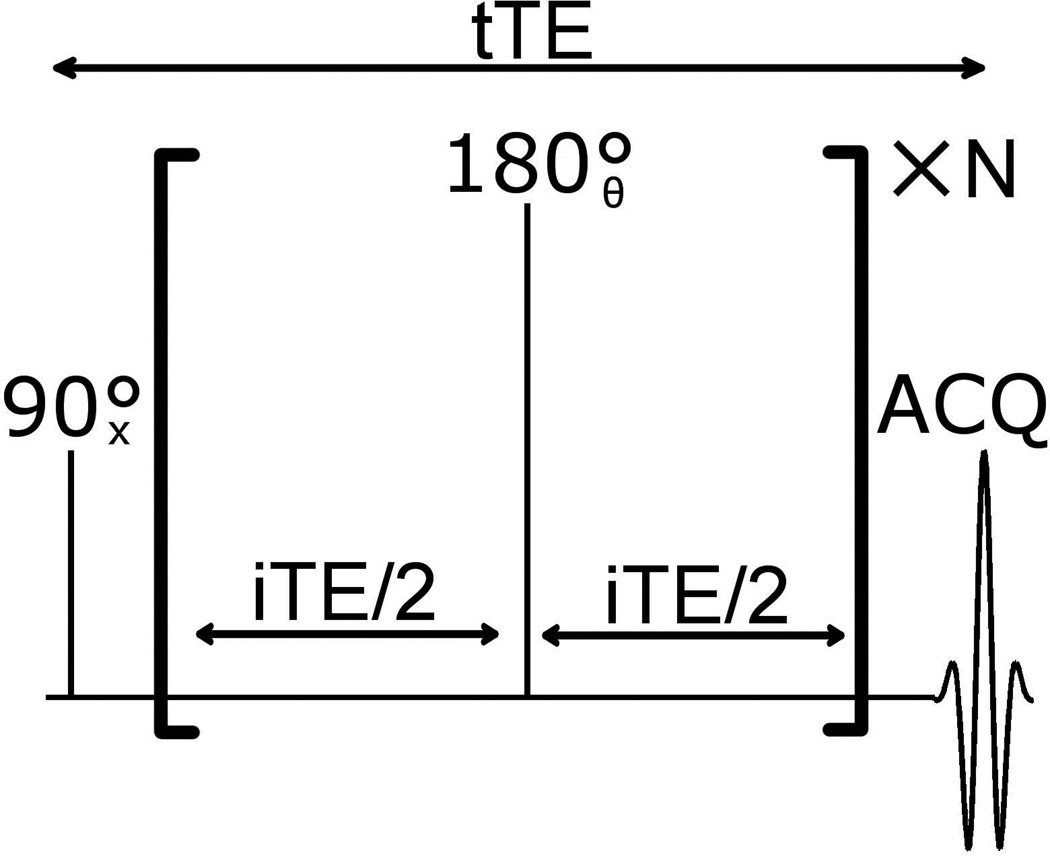

CPMG experiments

The signal of the methylene peak for oleic acid (OA), palmitic acid (PA), and cholesteryl benzoate (CB) was measured for a varying number of refocusing pulses while keeping the total echo time (tTE) fixed at 40 ms (pulse sequence shown in Figure 2). All lipid samples were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). For infinitely short pulses, the pulse sequence is described by tTE=N*iTE. iTE was the time between refocusing pulses for N > 2, and for N = 1, iTE = tTE. For experiments, the pulse sequence was run for each integer value of N ranging from 1 to Nmax. Nmax was 16 for 1 T experiments and 12 for 7 T experiments. A 0.1 ms block pulse was used for excitation and a 1.0 ms composite pulse (TPG pulse in ref. [11]) was used for B1-insensitve refocusing. The duration of the pulses was accounted for in the pulse sequence to ensure that tTE was constant for all values of N. For a CPMG with N refocusing pulses, the first N steps of MLEV-16 were used to phase cycle the refocusing pulse. The methylene signal was calculated as the integral of the magnitude spectrum in the 0.6–1.7 ppm region. The same pulse sequence was used on the 7T and 1T imaging systems.

Figure 2.

The CPMG pulse sequence used for testing how the number of refocusing pulses given in a fixed echo time affects the methylene signal.

CPMG simulations

Simulations of oleic acid under a Car-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) pulse sequence were performed using the Spinach v. 1.5.2440 package for MATLAB [12]. For all simulations (and experiments), tTE was 40ms, and the number of refocusing pulses was varied. The Zeeman Hamiltonians used for the simulations are given in Table 1. H1 was used to show how the response of Oleic acid depends on the fine details, parameterized by “d”, of the Hamiltonian. A separate simulation was performed for d=0, 0.25 0.5, 0.75, 1.0. H1(d=0) corresponds to the Hamiltonian specified in Table 1 of reference [13]. H1(d=1) corresponds to the ChemBioDraw Ultra (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) simulation of oleic acid. H2 corresponds to the Hamiltonian specified in reference [14]. Scalar coupling values were: methyl-methylene, 8Hz; methylene-methylene, 7.1 Hz; methylene-allylic, 7.1 Hz; three bond allylic-olefinic, 6.2 Hz; four bond allylic-olefinic, 1.75 Hz; olefinic-olefinic, 16 Hz. All other scalar couplings including geminal methylene couplings were zero. The methylene signal was calculated as the integral of the magnitude spectrum in the 60 Hz region centered at the maximum point in the spectrum. The restricted basis IK-1 was used with basis level of 5, which only includes product states between directly coupled spins with order ≤ 5.

Table 1.

Zeeman Hamiltonian for Oleic acid simulations

| Spins | type | chemical shift (ppm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | H2† | ||

| 1,2,3 | methyl | 0.9−0.02d* | 0.9 |

| 4,5 | methylene | 1.29−0.03d | 1.44 |

| 6,7 | methylene | 1.29−0.03d | 1.35 |

| 8,9 | methylene | 1.29−0.03d | 1.39 |

| 10,11 | methylene | 1.29+0.01d | 1.39 |

| 12,13 | methylene | 1.29+0.04d | 1.39 |

| 14,15 | methylene | 1.29 | 1.39 |

| 16,17 | allylic | 2.18−0.02d | 2.09 |

| 18 | olefinic | 5.45−0.11d | 5.43 |

| 19 | olefinic | 5.45−0.11d | 5.43 |

| 20,21 | allylic | 2.18−0.02d | 2.09 |

| 22,23 | methylene | 1.29 | 1.39 |

| 24,25 | methylene | 1.29+0.04d | 1.39 |

| 26,27 | methylene | 1.29−0.03d | 1.39 |

| 28,29 | methylene | 1.29+0.04d | 1.39 |

| 30,31 | methylene | 1.64 | 1.64 |

| 32,33 | methylene | 2.32 | 2.29 |

simulated values of d were 0,0.25,0.5,0.75,1.0

values from ref. [14], Table 1 (1H, free).

Comparison of precision between SSE- and MSE-HOT

Three ex vivo porcine rib samples from a grocery store were imaged to measure the temperature precision of SSE-HOT and MSE-HOT. Samples were allowed to rest in 37 °C air for one hour before imaging. Five temperature images were acquired with both the SSE-HOT and MSE-HOT pulse sequences. MSE-HOT images were echo averaged then converted to temperature as described above. SSE-HOT images were converted to temperature without echo averaging. SSE-HOT imaging parameters were the same as MSE-HOT except that for SSE-HOT t2 was 20 ms to maximize SNR. Regions of interest (ROIs) were manually drawn over the red marrow region of the sample. The standard deviation of temperature (i.e. precision) was calculated across the five images for each marrow voxel. The resulting distributions of standard deviation were either overlaid on T2-weighted image of the RBM sample or plotted in a histogram.

Accuracy determination

The accuracy of MSE-HOT temperature measurements was measured during a mock hyperthermia procedure. The accuracy was measured by taking the root mean squared difference (RMSD) between fiberoptic temperature measurements and MSE-HOT temperature measurements. A fiberoptic temperature probe (model 3100 sensors, Luxtron Corp., Santa Clara, California, USA) was placed in a hole drilled in the red marrow. The RBM sample with probe was then placed inside the MRI. The temperature of the sample was manipulated by changing the temperature of the air (Tair) blown over the sample. Before beginning the experiment, Tair was set to 37 °C and the sample was allowed to rest for one hour. Next, a time course of 30 images was initiated which lasted for 64 minutes. The Tair was 37 °C for 10 minutes, then switched to 45 °C for 25 minutes, then switched back to 37 °C for the remainder of the experiment. During imaging, fiberoptic temperature data was read and time-stamped from the Luxtron serial port every 15 s using MATLAB. For accuracy analysis, the fiberoptic measurements were compared to the MSE-HOT measurements in the voxel that contained the fiberoptic temperature probe.

MSE-HOT accuracy was measured using two methods. The first method quantifies the absolute temperature accuracy of the technique by taking the RMSD between the fiberoptic and MSE-HOT measurements after they had been plotted on the same x axis. The second method quantifies the accuracy of MSE-HOT temperature change measurements. In order to measure the temperature change accuracy, each temperature time-series was shifted on the temperature axis so that the average MSE-HOT and fiberoptic measurements were equal during the first 10 minutes of imaging when Tair was 37 °C. The temperature change accuracy was calculated as the RMSD between the fiberoptic timecourse and the shifted MSE-HOT timecourse.

Preparation and Imaging of Emulsions

Emulsions were prepared to test the dependence of iZQC frequency on lipid saturation and the susceptibility of the water compartment. One gram of emulsifying wax (Milliard, item # MIL-EMSFWX-16-A) and 2 g of vegetable oil (Wesson) or coconut butter (MaraNatha) were put in a plastic 10 mL tube. The tube was placed in a 60 °C water bath and sonicated in a benchtop ultrasound cleaner (Branson Ultrasonics, model 1510) until the wax and oil became a homogeneous mixture. A 4 mL 60 °C solution of 5 mM Prohance (Bracco Diagnostics) with or without 0.5 mM Dy(III)Br3 (Sigma-Aldrich, CAS Number 14456-48-5) was mixed in the oil/wax mixture. The mixture was removed from the sonicator bath and placed in an ice bath. The emulsions rested at room temperature for 4 days before imaging. The emulsions were imaged with the SSE-HOT pulse sequence using the same imaging parameters that were used for imaging the red marrow.

Results

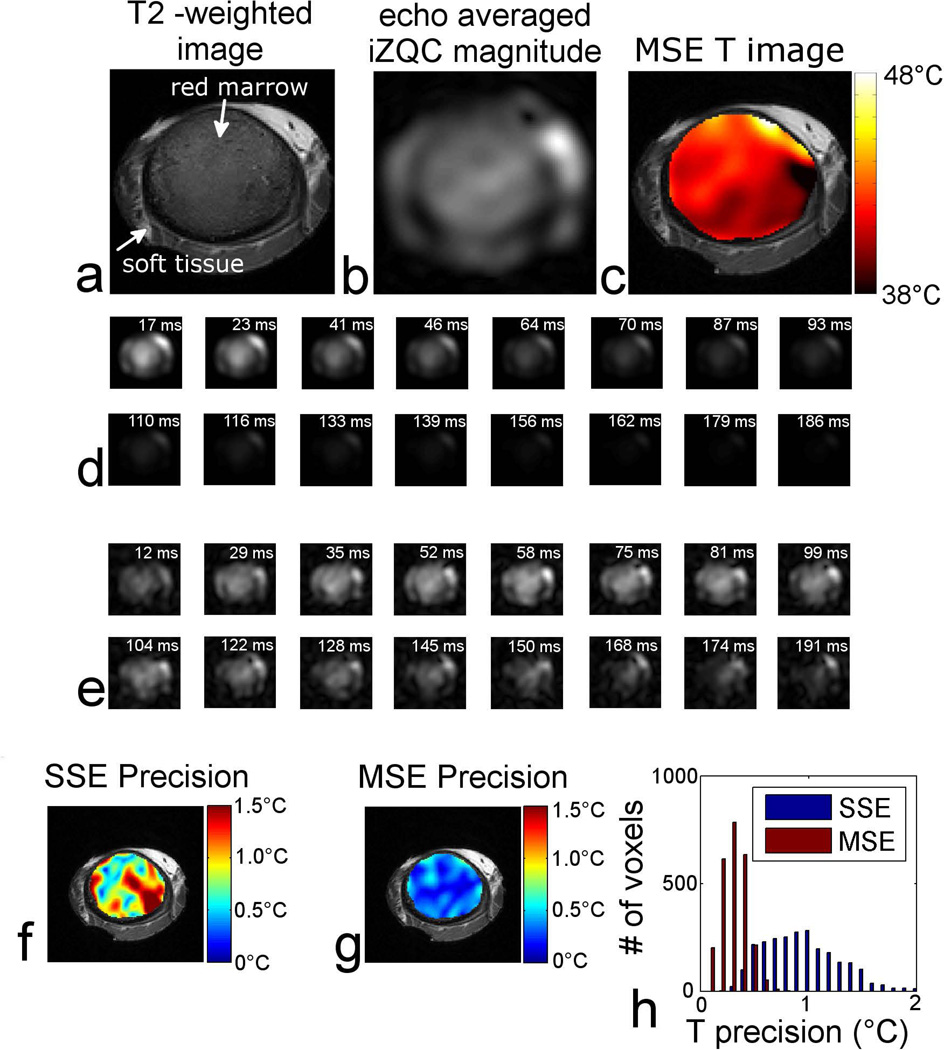

A representative MSE-HOT dataset is shown in Figure 3, and a T2-weighted image of ex vivo porcine red marrow is shown in Figure 3a. Figure 3b shows the magnitude image of the echo-averaged d(x,y) images. Figure 3c shows the temperature image generated from the phase of d(x,y) overlaid on the T2-weighted image. Figure 3d shows a fat-selective image for each SQC echo in the MSE-HOT echo train. As the echo time increases, the signal intensity decreases due to the spin-spin relaxation of the methylene protons. Figure 3e shows the iZQC images generated by the MSE-HOT echo train. The time dependence of image intensity was quite different for iZQCs than for the SQCs; the iZQC signal increased as time progressed for echo times less than 60 ms, and decreased for later times Figure 3f and Figure 3g show temperature precision maps of SSE-HOT and MSE-HOT respectively. The precision maps are overlaid on T2-weighted images of red marrow. Qualitatively, the process of echo-averaging enabled by MSE-HOT substantially improved the temperature precision of MSE-HOT over the SSE-HOT sequence. The histogram in Figure 3h shows the distribution of temperature precision within the marrow cavity. In this experiment the precision was improved from 1.1 °C (SSE-HOT) to 0.3 °C (MSE-HOT), an almost four-fold improvement.

Figure 3.

A representative MSE-HOT dataset. a) T2-weighted image of porcine RBM sample. b) magnitude of d(x,y). c) temperature image overlaid on T2-weighted image. d) fat SQC image for the 16 SQC echoes created by MSE-HOT. e) methylene-water iZQC magnitude image for the 16 iZQC echoes. f) SSE-HOT precision map overlaid on T2-weighted image. g) MSE-HOT precision map overlaid on T2-weighted image. h) histogram of the precision data in f&g.

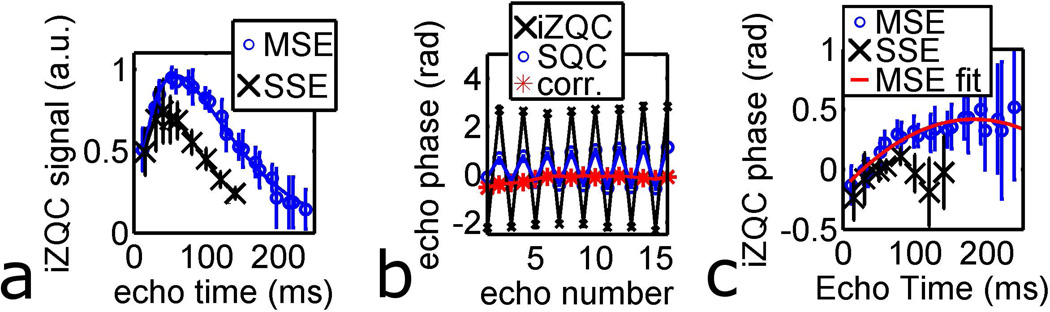

Figure 4 characterizes the time dependence of the fat-water iZQC signal in more detail. Figure 4a shows the time-dependence of the iZQC signal magnitude for the SSE-HOT and MSE-HOT pulse sequences; the maximum MSE-HOT signal was 40% greater than the maximum SSE-HOT signal. Figure 4b shows the phase of the SQC and iZQC signal, as well as the corrected phase difference for one voxel from a representative MSE-HOT dataset. It is clear that the SQC and iZQC phase jump from echo to echo, but the corrected phase difference does not. Figure 4c shows the phase of the MSE-HOT (φMSE(TE)) and SSE-HOT (φSSE(TE)) pulse sequences as a function of echo time. For both pulse sequences, the phase increases by 0.4 rad from 10 ms to 80 ms. At echo times greater than 80 ms φMSE(TE) phase levels off and φSSE(TE) decreases. A fit to the MSE-HOT phase is shown in red (Equation 4), and this was the phase correction curve used during echo averaging.

Figure 4.

The iZQC signal as a function of echo time. All error bars are the standard deviation of 9 voxels total from 3 different porcine RBM samples. a) iZQC signal magnitude vs echo time for MSE and SSE pulse sequences. b) The uncorrected phase of iZQC and SQC echoes and φMSE for the MSE sequence. c) The corrected phase of the iZQC echo (φ̄MSE) as a function of echo time.

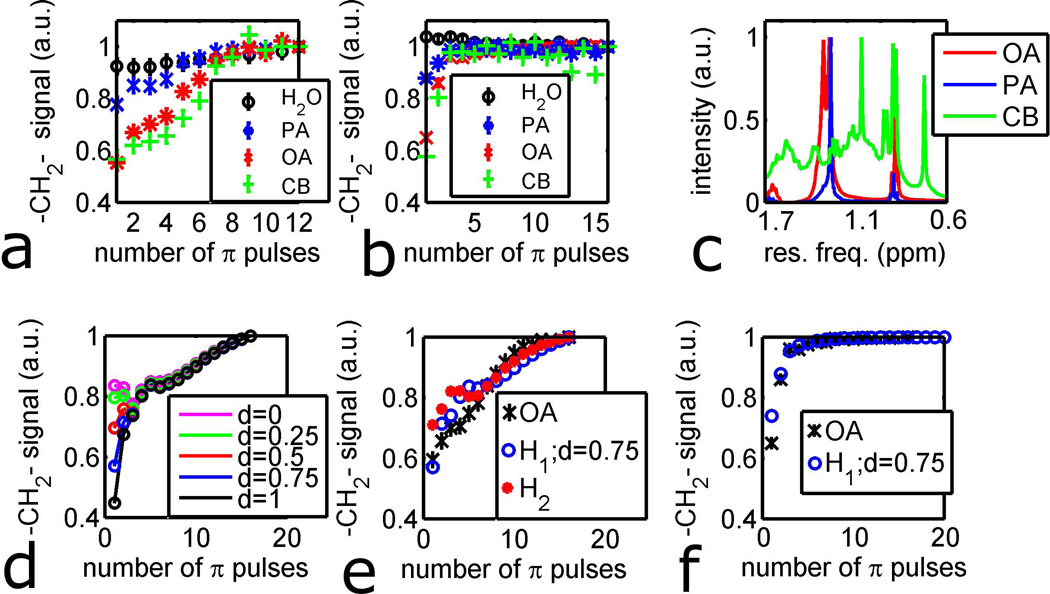

As seen in Figure 4a, the MSE sequence results in greater signal magnitude than SSE-HOT. To better understand the effect of a MSE pulse sequence on fat, simulations and experiments were performed with the CPMG sequence (Figure 2) on water, PA, OA, and CB (Figure 5). Figure 5a shows the water signal and methylene signal of the three lipids as a function of number of pulses (N in Figure 2) for tTE = 40 ms at 7 T. The signal of water and PA depend very weakly on pulse number, while the signal of OA and CB depend more strongly on pulse number. Figure 5b shows the same experiment at 1 T. As can be seen in Figure 5b, far fewer pulses were needed to maximize the signal at 1 T than at 7 T. Similar to the 7 T case, PA and water had very weak dependence on N, while CB and OA had a much stronger dependence. Figure 5c shows the dispersion of chemical shifts in the methylene region (0.6 ppm – 1.7 ppm) for a sample shimmed so that the solvent peak (CHCl3) was less than 1 Hz (3 ppb). It is clear from Figure 5c that the range of chemical shifts associated with –CH2- protons varies widely between the three lipids. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the PA and OA –CH2- groups were 10 ppb and 60 ppb respectively. The CB spectrum showed resonances spanning the entire alkane region.

Figure 5.

Simulations and experiments of methylene protons on lipids under a CPMG experiment. Error bars are the standard deviation of all water data-points at the same field strength. a) Experimental methylene signal of water, palmitic acid (PA), oleic acid (OA), and cholesteryl benzoate (CB) at 7T. b) Experimental methylene signal of water, PA, OA, and CB at 1T. c) high resolution spectra of alkane region of PA, OA, and CB at 360 MHz. Solvent linewidths were less than 3 ppb. d) Simulated methylene signal under CPMG pulse sequence with Hamiltonian H1 at 7 T. e) simulated and experimental methylene signal of OA at 7 T. f) simulated and experimental methylene signal of OA at 1T.

In order to understand the different behavior of the three lipids under the CPMG pulse sequence, the spin dynamics of OA was simulated. Figure 5d shows the simulated methylene signal for OA with the Hamiltonian H1 (Table 2). As the d parameter decreased, the dispersion of methylene chemical shifts also decreased, resulting in higher signal for lower N (Figure 5d). For N = 1, the methylene signal for d=0 is double that of d=1. Figure 5e shows the simulated OA signal for Hamiltonians H1(d=0.75) and H2, as well as the experimental OA data at 7 T. Both simulations and experiments showed that increasing N resulted in more methylene signal. The simulated data tended to over-predict the signal at N <7 and under-predict the signal at N>7. At 1 T (Figure 5f) the simulations and experiment again showed that fewer pulses are needed to achieve maximal methylene signal.

Table 2.

Accuracy of MSE-HOT

| Experiment no. |

Temperature accuracy |

|

|---|---|---|

| T RMSD* | ΔT RMSD† | |

| 1 | 0.6 °C | 0.4 °C |

| 2 | 2.4 °C | 0.7 °C |

| 3 | 0.9 °C | 1.0 °C |

| 4 | 3.4 °C | 0.4 °C |

| 5 | 1.2 °C | 0.4 °C |

| mean | 1.7 °C | 0.6 °C |

absolute temperature accuracy

relative temperature accuracy

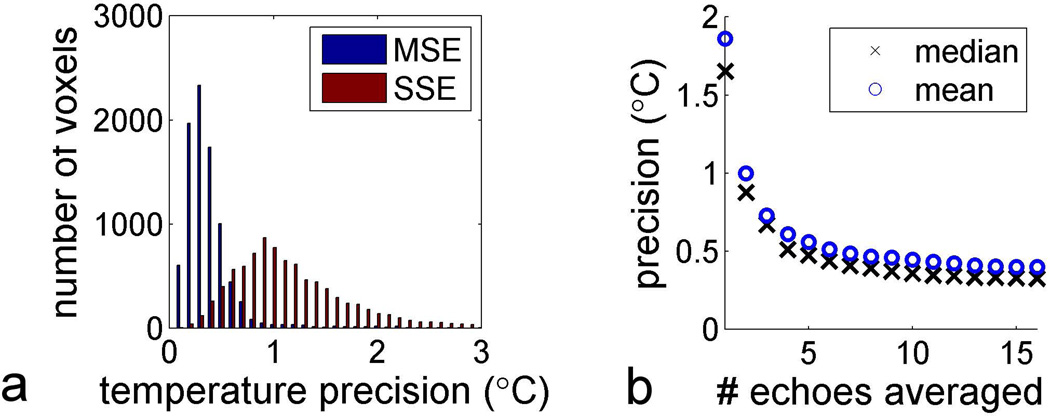

Next, the improvement in precision was characterized for the MSE-HOT and SSE-HOT pulse sequences. Precision maps and histograms similar to those in Figure 3c–e were generated for three marrow samples, and the precision of all three samples are plotted simultaneously on Figure 6a. The median precision for SSE-HOT was 0.9 °C while the median precision for MSE-HOT was 0.3 °C, a three-fold improvement. Figure 6b shows the mean and median precision for MSE-HOT as a function of the number of images averaged. For example, the data point corresponding to the mean precision at four echoes the temperature precision achieved by averaging just the first four phase difference images (d1(x,y) +…+ d4(x,y)), then converting the resulting sum to temperature. As can be seen in Figure 6b, the precision improves from 1.6 °C at the first echo to 0.4 °C by the sixth echo. By the sixteenth echo, the median precision improves only by an additional 0.1 °C to a value of 0.3 °C.

Figure 6.

Precision summary of MSE-HOT. a) Temperature precision within the marrow region for MSE and SSE sequences (N=3 marrow samples). b) Mean and median precision as a function of number of echoes averaged. For example for the data point with value “5” on the x axis, the first 5 MSE echoes were averaged. Each data point is generated from a separate histogram similar to the one in part a.

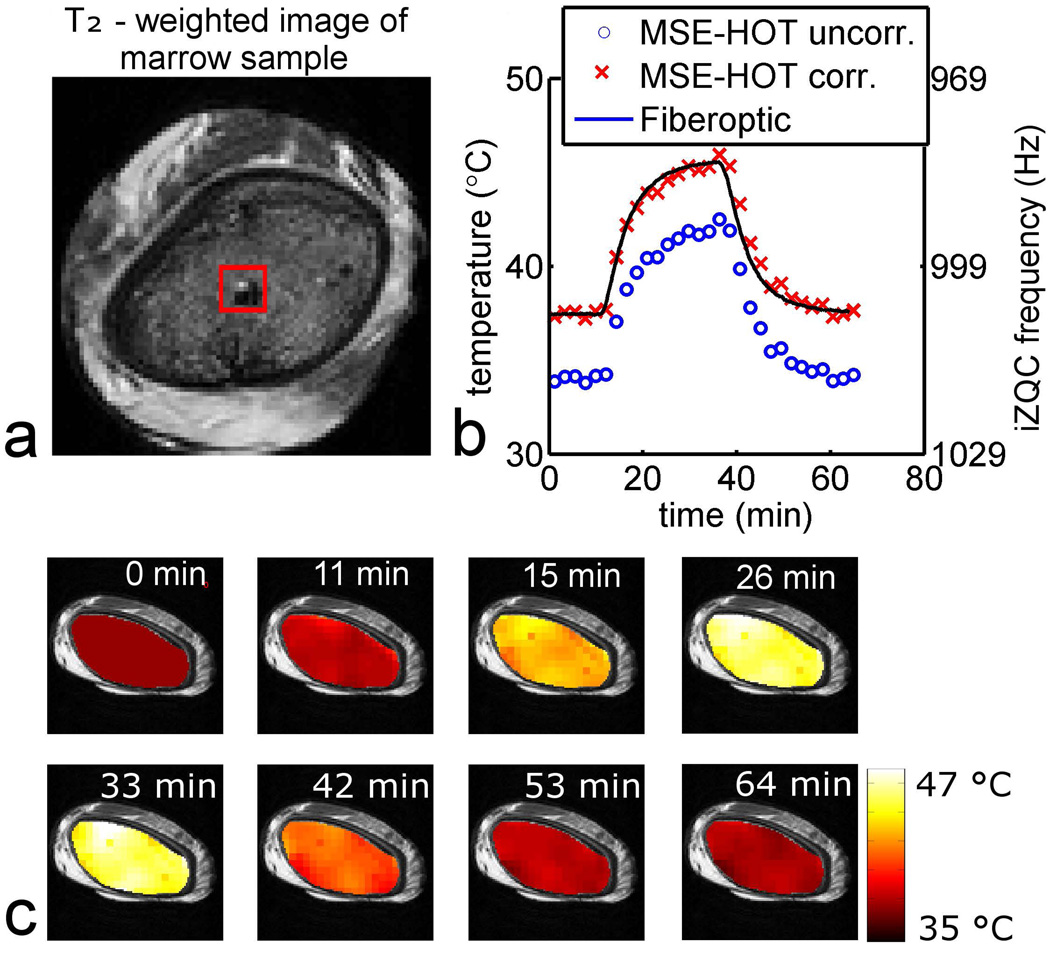

The total accuracy and precision was quantified by calculating the RMSD between MSE-HOT and fiberoptic temperature measurements as illustrated Figure 7. Figure 7a shows a T2-weighted image of porcine red marrow with the ROI used for analysis in red. The fiberoptic temperature probe is the dark region on the bottom right corner of the red ROI. Figure 7b shows fiberoptic and MSE-HOT temperature measurements during heating and cooling of a red marrow sample. In some datasets, including the one shown in Figure 7b, there was a large systematic error in the MSE-HOT temperature measurements (Figure 7b, MSE-HOT uncorr.) For quantifying the accuracy of temperature change measurements, the MSE-HOT data were corrected so that he pre-heating MSE-HOT measurements matched the preheating fiberoptic measurements (Figure 7b, MSE-HOT corr.) The temperature change images from which the measurements in Figure 7b were derived are shown in Figure 7c. A summary of the RMSD between MSE-HOT and fiberoptic measurements is shown in Table 2. The experiment shown in Figure 7 is Experiment 4 in the table. A key finding was that the average temperature change RMSD was 0.6 °C, which is an acceptable level of accuracy for many hyperthermia procedures.

Figure 7.

Representative dataset for the mock hyperthermia treatment. a) T2-weighted image of RBM sample. The ROI used to calculate temperature is outlined in red. b) the fiberoptic and MSE-HOT temperature measurements obtained during heating and cooling of the RBM sample. c) temperature maps overlaid on T2-weighted images during heating and cooling of RBM sample.

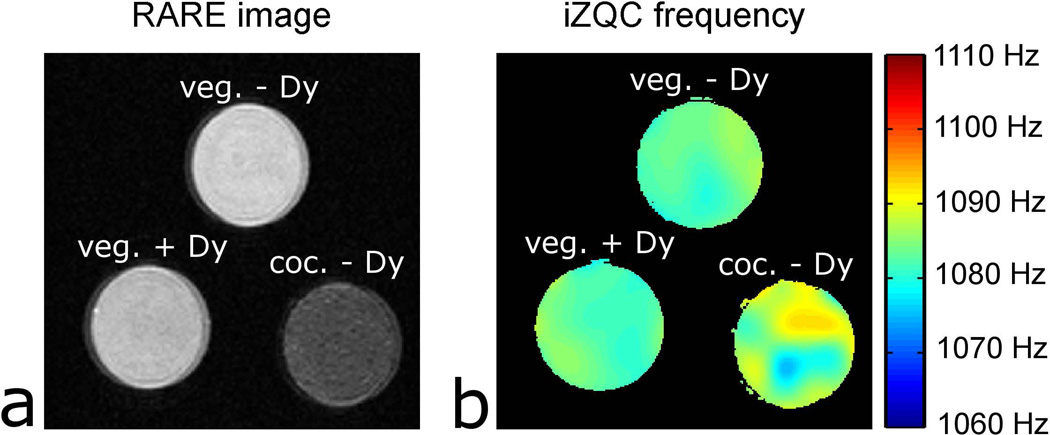

Finally, emulsions were prepared to determine if the iZQC frequency is influenced by lipid saturation or the susceptibility of the water compartment. Figure 8 shows images of three emulsions: vegetable oil and water without Dy(III), vegetable oil with water and 0.5mM Dy(III), and coconut butter and water without Dy(III). The coconut butter emulsion tended to have lower SNR then vegetable oil emulsions because the coconut butter is a semisolid at room temperature with shorter T2 than vegetable oil. Qualitatively, the mean iZQC frequency (Figure 8b) was not different between the three emulsions. The iZQC frequency (mean ± standard deviation of 5 samples) at 23 °C was 1084 ± 4 Hz (coconut), 1080 ± 7 Hz (vegetable without Dy(III)), 1081 ± 4 Hz (vegetable with Dy(III)). A one-way ANOVA gave a P = 0.46 for the null hypothesis, suggesting that lipid type and water compartment susceptibility did not affect iZQC frequency.

Figure 8.

Images of emulsions. a) a RARE image of emulsions at 23 °C. b) iZQC frequency maps of emulsions.

Discussion

Precision and Accuracy of MSE-HOT

The primary goal of this study was to improve the SNR and temperature precision of the SSE-HOT pulse sequence. This goal was motivated by the observation made in a previous study that the SSE-HOT precision in red marrow was 0.8 °C even though a precision of less than 0.5 °C is preferred [4]. To overcome this limitation, a MSE spatial encoding scheme was added to SSE-HOT which allowed acquisition of up to 16 phase difference images (dn(x,y)) per excitation. The weighted sum of the 16 dn(x,y) images yielded a 3-fold improvement in SNR and temperature precision without increasing scan time. The resulting 0.3 °C temperature precision is more than sufficient for most hyperthermia procedures. Importantly, because the iMQC signal intensity has a (B0)2 field dependence [15], the temperature precision measured in this report will be superior to the precision achieved on a 3T clinical scanner. We have implemented MSE-HOT on a clinical scanner and are currently testing the pulse sequence performance on that system.

Comparison between MSE-HOT and fiberoptic temperature measurements showed that the RMSD error of MSE-HOT is on average 1.7 °C for absolute temperature and 0.6 °C for temperature change. The higher accuracy of temperature change measurements highlights the important observation that the inter-sample variation of α is much less than the inter-sample variation of ν37°C. Since α is the parameter that allows mapping of iZQC frequency to temperature change, it is not surprising that absolute temperature measurements are less accurate than temperature change measurements. As an example, for the experiment shown in Figure 7 there was a large systematic error in the absolute measurement (MSE-HOT uncorr. in the legend), but the temperature change measurement was very accurate (MSE-HOT corr.) The cause of inter-sample variation in ν37°C is discussed further below.

Suppression of J-coupling using MSE encoding

It has long been known that MSE and CPMG pulse sequences increase the signal intensity of fat [9,10]. Interestingly, the two most common types of fatty acids in humans, oleic acid and palmitic acid [16], have strikingly different behavior under the CPMG pulse sequence (Figures 5a&b). Far fewer pulses were needed to suppress J-coupling in PA than in OA. A likely explanation is related to the strong dependence of the CPMG signal on small chemical shift differences between neighboring methylene spins (Figure 5d.) As the value of d in H1 decreased, all methylene chemical shifts converged to a single value of 1.29 ppm, which for low pulse numbers resulted in a higher methylene signal. Because the dispersion of methylene frequencies for PA is much less than OA (Figure 5c) it is expected that fewer refocusing pulses are necessary to suppress J-coupling for PA, which is supported by the data (Figure 5a&b.) Interestingly, these data suggest that the contrast of fatty tissues will depend on both the amount of unsaturated lipids in the tissue as well as the number of refocusing pulses in the sequence. At 1 T, for example, the presence of unsaturated lipids like OA would tend to decrease the MR signal for N = 1 but not N = 4. Thus one would expect that the ratio of signal intensity for a one and four refocusing pulse image with same tTE would give a qualitative metric of tissue lipid unsaturation. In the context of MSE-HOT thermometry, these considerations show that temperature precision enhancement will be greater for tissues containing unsaturated fats.

Factors affecting the accuracy of absolute temperature measurements

In the thermometry literature, temperature measurements are often classified as either absolute or relative. Relative temperature measurements, such those obtained by phase mapping with a spoiled gradient recalled echo pulse sequence, measure changes in temperature relative to a pre-heating baseline [17]. An example of relative thermometry is thermal imaging of the soft tissue surrounding bone during palliative high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) treatment of bone metastasis [18–20]. For hyperthermia procedures, where the heating duration is approximately an hour and the temperature increase is often less than 5 °C, it would be more useful to measure temperature on an absolute scale. Absolute temperature measurements are often harder to achieve than relative measurements because many non-temperature-related factors can affect the MR signal phase such as motion, field drift, susceptibility interfaces between tissues [17,21,22]. In a previous study it was found that the SSE-HOT technique has an absolute temperature uncertainty in red marrow at 37 °C of ± 2 °C [4]. In this study, the RMSD between absolute measurements and a fiberoptic temperature measurement was on average 1.7 °C. These absolute temperature uncertainties stand in stark contrast to the remarkably consistent temperature coefficient in red marrow, which varied by ± 7% between samples [4]. Thus, this study attempted to determine the factors causing the absolute temperature uncertainty of MSE-HOT using emulsions as a model of red marrow tissue.

It is known that fat saturation varies in human tissue [16] and iron concentration varies in human red marrow [23]. In the case of lipid saturation, preparing the emulsion from vegetable oil (14% saturated fat by weight) or coconut oil (95% saturated fat by weight) did not affect the iZQC frequency. In the case of iron, it was hypothesized that since water-soluble iron is confined to the aqueous component of tissue, the difference in magnetic susceptibility between the aqueous and lipid compartments in marrow might vary between samples with different iron concentrations. To see if the susceptibility of the aqueous compartment affects temperature measurements, emulsions with 0 mM or 0.5 mM Dy(III) were prepared. Given the molar volume susceptibility of Dy(III) of 0.56 ppm/mM Dy(III) [24], 0.5 mM Dy(III) would give a paramagnetic contribution to susceptibility of water of 0.3 ppm or 90 Hz. Surprisingly, even this large susceptibility difference between the two compartments had no effect on iZQC frequency, suggesting that spatial heterogeneity in magnetic susceptibility on the distance scale of an adipocyte (~50 µm) does not affect the iZQC or measured temperature.

It is worth noting that the iZQC frequency detected in red marrow was lower than expected based on the emulsion data. For example, the iZQC frequency in red marrow at 37 °C is 1008 ± 6 Hz [4]. With a temperature coefficient of −3 Hz/°C, the iZQC frequency in red marrow at 23 °C would be 1050 Hz, which is considerably less than the iZQC frequency measured in emulsions in this study (1080 Hz −1084 Hz). This difference must correspond to a susceptibility difference between the regions with fat and the regions with water. Possible causes of this discrepancy could be the presence of non-spherical adipocytes or lipid droplets which shift the fat frequency. Alternatively, the susceptibility interface between bone and water (or lipids) could shift one compartment relative to the other in marrow but not in the emulsion.

Conclusion

A multi-spin-echo HOT pulse sequence was implemented that tripled the temperature precision of the SSE-HOT pulse sequence. The precision improvement resulted from suppression of J-coupling and echo averaging. The temperature change accuracy of MSE-HOT was determined to be on average 0.6 °C, which is acceptable for many hyperthermia procedures.

Acknowledgements

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Grant numbers: EB02122, T32EB001040.

References

- 1.Galiana G, Branca RT, Jenista ER, Warren WS. Accurate temperature imaging based on intermolecular coherences in magnetic resonance. Science. 2008;322(5900):421–424. doi: 10.1126/science.1163242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vathyam S, Lee S, Warren WS. Homogeneous NMR spectra in inhomogeneous fields. Science. 1996;272(5258):92–96. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warren WS, Richter W, Andreotti AH, Farmer BT., 2nd Generation of impossible cross-peaks between bulk water and biomolecules in solution NMR. Science. 1993;262(5142):2005–2009. doi: 10.1126/science.8266096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis RM, Warren WS. Intermolecular zero quantum coherences enable accurate temperature imaging in red bone marrow. Magn Reson Med. 2014 doi: 10.1002/mrm.25372. 10.1002/mrm.25372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Branca RT, Warren WS. In vivo NMR detection of diet-induced changes in adipose tissue composition. J Lipid Res. 2011;52(4):833–839. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D012468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branca RT, Warren WS. In vivo brown adipose tissue detection and characterization using water-lipid intermolecular zero-quantum coherences. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(2):313–319. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branca RT, Zhang L, Warren WS, Auerbach E, Khanna A, Degan S, Ugurbil K, Maronpot R. In vivo noninvasive detection of Brown Adipose Tissue through intermolecular zero-quantum MRI. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouchard LS, Warren WS. Multiple-quantum vector field imaging by magnetic resonance. J Magn Reson. 2005;177(1):9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stables LA, Kennan RP, Anderson AW, Gore JC. Density matrix simulations of the effects of J coupling in spin echo and fast spin echo imaging. J Magn Reson. 1999;140(2):305–314. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williamson DS, Mulken RV, Jakab PD, Jolesz FA. Coherence transfer by isotropic mixing in Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill imaging: implications for the bright fat phenomenon in fast spin-echo imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35(4):506–513. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odedra S, Wimperis S. Use of composite refocusing pulses to form spin echoes. J Magn Reson. 2012;214(1):68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hogben HJ, Krzystyniak M, Charnock GT, Hore PJ, Kuprov I. Spinach--a software library for simulation of spin dynamics in large spin systems. J Magn Reson. 2011;208(2):179–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stokes AM, Feng Y, Mitropoulos T, Warren WS. Enhanced refocusing of fat signals using optimized multipulse echo sequences. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69(4):1044–1055. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fast J, Mossberg AK, Nilsson H, Svanborg C, Akke M, Linse S. Compact oleic acid in HAMLET. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(27):6095–6100. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutteridge S, Ramanathan C, Bowtell R. Mapping the absolute value of M0 using dipolar field effects. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(5):871–879. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malcom GT, Bhattacharyya AK, Velez-Duran M, Guzman MA, Oalmann MC, Strong JP. Fatty acid composition of adipose tissue in humans: differences between subcutaneous sites. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50(2):288–291. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/50.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rieke V, Butts Pauly K. MR thermometry. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27(2):376–390. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bucknor MD, Rieke V, Do L, Majumdar S, Link TM, Saeed M. MRI-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation of bone: evaluation of acute findings with MR and CT imaging in a swine model. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;40(5):1174–1180. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Catane R, Beck A, Inbar Y, Rabin T, Shabshin N, Hengst S, Pfeffer RM, Hanannel A, Dogadkin O, Liberman B, et al. MR-guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS) for the palliation of pain in patients with bone metastases--preliminary clinical experience. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(1):163–167. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gianfelice D, Gupta C, Kucharczyk W, Bret P, Havill D, Clemons M. Palliative treatment of painful bone metastases with MR imaging--guided focused ultrasound. Radiology. 2008;249(1):355–363. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2491071523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Poorter J. Noninvasive MRI thermometry with the proton resonance frequency method: study of susceptibility effects. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34(3):359–367. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters NH, Bartels LW, Sprinkhuizen SM, Vincken KL, Bakker CJ. Do respiration and cardiac motion induce magnetic field fluctuations in the breast and are there implications for MR thermometry? J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29(3):731–735. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isokawa M, Kimura F, Matsuki T, Omoto E, Otsuka K, Kurokawa H, Togami I, Hiraki Y, Kimura I, Harada M. Evaluation of bone marrow iron by magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Hematol. 1997;74(6):269–274. doi: 10.1007/s002770050298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egami S, Monjushiro H, Watarai H. Magnetic susceptibility measurements of solutions by surface nanodisplacement detection. Anal Sci. 2006;22(9):1157–1162. doi: 10.2116/analsci.22.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]