Abstract

Inpatient and skilled nursing facility (SNF) cost sharing in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans may reduce unnecessary use of these services. However, large out-of-pocket expenses potentially limit access to care and encourage beneficiaries at high risk of needing inpatient and postacute care to avoid or leave MA plans. In 2011 new federal regulations restricted inpatient and skilled nursing facility cost sharing and mandated limits on out-of-pocket spending in MA plans. After these regulations, MA members in plans with low premiums averaged $1,758 in expected out-of-pocket spending for an episode of seven hospital days and twenty skilled nursing facility days. Among members with the same low-premium plan in 2010 and 2011, 36 percent of members belonged to plans that added an out-of-pocket spending limit in 2011. However, these members also had a $293 increase in average cost sharing for an inpatient and skilled nursing facility episode, possibly to offset plans’ expenses in financing out-of-pocket limits. Some MA beneficiaries may still have difficulty affording acute and postacute care despite greater regulation of cost sharing.

The Medicare Advantage (MA) program, an alternative to traditional Medicare, offers beneficiaries a market for choosing between private insurance plans with different premiums and benefits. MA plans can employ cost-sharing designs to manage their members’ health care use and spending, including inpatient and skilled nursing facility (SNF) coverage. How enrollees in MA plans gain access to these expensive, and often critical, services has important implications for them and the plans.

Each MA plan’s total insurance package must at least be equivalent to the estimated actuarial value of traditional Medicare’s insurance benefit. Cost sharing for a particular service may be greater or less than the cost sharing for that service under traditional Medicare.

High cost sharing for inpatient and SNF care may limit unnecessary use of these services. However, MA members with serious medical problems might not be able to reduce their use of acute and postacute care without harming their health. Large out-of-pocket expenses for critical services may prevent MA members from obtaining necessary treatment.1,2

Cost-sharing requirements for inpatient and SNF care can also influence whether MA plans appeal to beneficiaries with a range of health needs.1–5 To attract beneficiaries, MA plans often offer coverage for services that are not covered in traditional Medicare, including dental care, fitness memberships, and eyeglasses. If cost sharing is low for these optional benefits but high for critical services such as inpatient care, healthy beneficiaries may be more satisfied with MA plans than beneficiaries with serious health conditions are. This pattern could lead to sicker members’ exiting MA plans that impose higher copayments for acute and postacute care.

The federal government has recently employed two broad strategies to regulate out-of-pocket spending for MA beneficiaries. First, starting in 2011 the Affordable Care Act required that cost sharing in MA plans not exceed that of traditional Medicare’s actuarial value for specific services, including care in skilled nursing facilities. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) also imposed cost-sharing limits for inpatient stays.6,7 This approach is meant to limit MA plans from designing benefits to attract and retain healthy Medicare beneficiaries while discouraging enrollment among beneficiaries with intensive health care needs.

Second, in 2011 CMS instituted mandatory overall out-of-pocket spending limits of $6,700 for all plans. Plans had the option of offering a lower, voluntary limit of $3,400. Those that did were allowed more flexibility in setting cost-sharing levels for individual services, such as inpatient care.6,7 This strategy is designed to ensure that beneficiaries have a fixed amount of protection from medical expenses across all types of services. Traditional Medicare does not offer an out-of-pocket limit; beneficiaries can purchase private supplemental insurance to cover out-of-pocket expenses.3

Additional programs protect low-income beneficiaries from high out-of-pocket expenses in traditional Medicare and MA plans. The federal government requires state Medicaid programs to cover Medicare cost sharing for beneficiaries with incomes below the federal poverty level. People with incomes below 150 percent of poverty may qualify for some assistance with premiums for Medicare Part B, which covers services such as doctor visits and lab tests, or Part D prescription drug coverage costs.8,9 However, these limited subsidies do not necessarily target the areas where low-income beneficiaries have the greatest out-of-pocket expenses. For example, Medicare beneficiaries projected to be eligible for Part D subsidies (without Medicaid coverage) spend more on nondrug medical expenses than they do on prescription drugs.10

There have been few empirical investigations of cost-sharing requirements for MA enrollees, and these previous analyses have not assessed the expected out-of-pocket spending for the critical population of low-income beneficiaries who participate in needs-based programs. Using individual-level MA enrollment and plan benefit data, we calculated MA beneficiaries’ expected out-of-pocket expenses for an inpatient and SNF stay. We compared the expected expenses for all beneficiaries to those for low-income MA beneficiaries.

Adding an out-of-pocket spending limit while restricting cost sharing for expensive services may have been difficult for some MA plans to finance. Plans may have offset the expense of adding an out-of-pocket limit by increasing cost-sharing requirements. We examined benefit changes in plans that do not charge their members any premiums beyond what beneficiaries would pay for traditional Medicare coverage. Among members of these plans with low premiums, we compared inpatient and SNF cost-sharing changes for members of plans that added an out-of-pocket limit with concurrent trends for members of plans that already had an out-of-pocket limit prior to 2011.

Study Data And Methods

DATA SOURCES AND STUDY POPULATION

We used person-level enrollment records from the 2011 Medicare Advantage Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS).We analyzed two types of plans: standard MA plans open to all Medicare beneficiaries; and Special Needs Plans (SNPs), which limit enrollment to beneficiaries with dual eligibility for Medicaid, a chronic condition, or the need for an institutional level of long-term care. Plans with at least 1,000 members were required to report HEDIS data to CMS.11 Using CMS data and Plan Finder website descriptions, we identified plans’ benefits; managed care models; Part D coverage;12 and, for SNPs, targeted population.13 We linked the HEDIS data to the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File to obtain demographic characteristics and enrollment status for Medicaid and the Part D low-income subsidy programs.

Among 13.17 million beneficiaries in the HEDIS 2011 data, we excluded 2.12 million beneficiaries in plans that had employer sponsorship, limited enrollment (cost, medical savings account, and state-licensed point-of-service plans), or fewer than fifty members. Another 245,115 individuals could not be linked to CMS enrollment data, and 491,860 lived in Puerto Rico or outside the United States. Three hundred ninety-six plans with 1.76 million members had plan identifiers that could not be merged to plan-level benefits data. More than 60 percent of these members belonged to plans from two large MA contractors based in California and Pennsylvania. Our final sample included 8.17 million beneficiaries across 1,841 plans (7.42 million people in 1,508 MA plans and 1.13 million people in 333 SNPs).

To assess MA out-of-pocket expenses among people with low incomes, we identified beneficiaries who participated in needs-based programs that provide limited subsidies for Medicare- related costs. This subgroup included beneficiaries enrolled in the Part D low-income subsidy program (income limit: 150 percent of poverty) and beneficiaries with Medicaid subsidies for the Part B premium (income limit: 135 percent of poverty). These programs’ individual asset limits in 2011 were $11,140 and $6,680, respectively, and excluded the value of individuals’ homes.8,9 Further details about eligibility requirements for these programs are included in the online Appendix,14 including information about a limited number of state exceptions to these federal eligibility criteria. We identified beneficiaries’ participation in these programs as of January or their first month of Medicare enrollment in 2011. In our analysis of this low-income subgroup, we excluded beneficiaries who had full Medicaid or Medicaid coverage of their MA cost-sharing amounts (income limit: 100 percent of poverty) because we wanted to focus on beneficiaries who were liable for expected out-of-pocket expenses. In effect, this subgroup mainly comprises MA beneficiaries with incomes slightly above the federal poverty level and relatively few assets.

ANALYSES

We report our results separately for MA plans according to whether members pay additional premiums. Plans can cost beneficiaries nothing beyond the Part B premium (zero-premium plans) or have an additional premium (added-premium plans).We report the combined cost of the Part B premium ($96.40 per month in 2011 for most beneficiaries)15 and MA premiums, including deductions for any refunds offered by plans for members’ Part B premiums. Within each premium category, we weighted plans by their number of members and identified plans in the top quartile for percentage of members receiving premium or Part D subsidies.

Using plans’ benefit data, we calculated the expected cost-sharing amounts for a three- or seven-day inpatient stay followed by a seven-or twenty-day skilled nursing facility stay. We assumed that beneficiaries would use in-network inpatient and SNF services. Most plans charge a flat copayment per stay or daily copayments, which might vary depending on length-of-stay. We capped the expected costs if a plan had an out-of-pocket limit that applied to inpatient, SNF, or all plan services. We do not report total expected costs for the few plans that only charged coinsurance for inpatient or SNF services because we had no data on payment rates to be able to translate the coinsurance rate into an expected dollar amount.

Many dual Special Needs Plans describe their cost-sharing amounts as $0 or greater than $0, depending on a member’s level of Medicaid coverage, so we report two estimates for dual SNPs. The first estimate assumes that members paid $0 out of pocket; the higher estimate bases expenses on the amount that is greater than $0 and excludes beneficiaries whose secondary cost-sharing requirement is coinsurance. Plans that listed only one cost-sharing amount have that value used in both estimates.

To quantify cost-sharing changes from 2010 to 2011, we examined 2010 HEDIS and Plan Finder benefits data for 2.29 million members who belonged to the same zero-premium plan in 2010 and 2011. This approach allowed us to exclude beneficiaries who switched plans to intentionally change their cost sharing. It also excluded beneficiaries in plans that changed their premiums in response to the new regulations. We compared changes in cost sharing for members based on whether they already had an out-of-pocket limit in 2010 or gained one in 2011, when CMS began requiring plans to offer spending caps.

LIMITATIONS

Our analysis had several limitations. We analyzed expected inpatient and skilled nursing facility costs based on plans’ benefit descriptions, not Medicare Advantage enrollees’ actual out-of-pocket expenditures. Because out-of-pocket caps also apply to outpatient care, members may reach a spending limit before a hospitalization or SNF stay and have no cost sharing for those services. We did not control for what type of plan and benefit packages were available to beneficiaries based on where they lived. The national trends we present may not have been uniform across every geographic region and plan type in the United States. Because of incomplete plan identifiers on the HEDIS data, our results include a large share of MA beneficiaries but might not be representative of the MA population in the Pacific and Mid-Atlantic regions.

In a cross-sectional analysis, we could not determine whether previous exposure to out-of-pocket expenses may have prompted people to join financial assistance programs; nor can we account for whether people belong to MA plans that actively screen their members for financial assistance eligibility.16 Given low take-up rates for premium and Part D subsidies,17,18 our analysis probably underestimated the number of low-income MA beneficiaries who actually qualified for these benefits.

Finally, we did not address several other factors that may influence beneficiaries’ use of acute and postacute services. To reduce health care costs, MA plans can restrict members to plan network providers and employ care management strategies. CMS implemented the new regulations in the same year in which payment rates for MA plans were frozen,19 which may have affected how plans changed their benefits.

Study Results

CHARACTERISTICS OF MEDICARE ADVANTAGE AND SPECIAL NEEDS PLAN ENROLLEES

The majority of MA members (55 percent) belonged to zero-premium plans (Exhibit 1). Almost 80 percent of SNP enrollees belonged to dual SNPs (Appendix Exhibit A1),14 so we focused on these members in our discussion of results. Results for members of chronic condition and institutional SNPs are presented in the Appendix.14

EXHIBIT 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics Of Members In Standard Medicare Advantage Plans, By Premium Level And Receipt Of Subsidies, 2011

| Zero-premium plansa | Added-premium plansb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | All | With subsidiesc | All | With subsidiesc |

| Number of members | 4,045,498 | 504,699 | 3,374,747 | 330,863 |

| AGE | ||||

| Under age 65 | 12% | 27% | 12% | 30% |

| Age 65–74 | 48 | 38 | 46 | 33 |

| Age 75–84 | 30 | 26 | 30 | 26 |

| Ages 85 and older | 11 | 9 | 12 | 11 |

| SEX | ||||

| Female | 55 | 61 | 57 | 66 |

| RACE | ||||

| White | 79 | 66 | 89 | 79 |

| Black | 13 | 23 | 7 | 17 |

| Other | 8 | 10 | 4 | 5 |

| RECEIPT OF FINANCIAL SUBSIDIES | ||||

| No financial subsidies | 81 | —d | 85 | —d |

| Premium/Part D subsidies | 13 | 100 | 10 | 100 |

| Full Medicaid/Medicaid coverage of Medicare cost sharing | 6 | —d | 5 | —d |

| REGION | ||||

| New England | 3 | 2 | 6 | 5 |

| Middle Atlantic | 11 | 12 | 17 | 17 |

| East North Central | 12 | 9 | 17 | 13 |

| West North Central | 4 | 3 | 8 | 6 |

| South Atlantic | 28 | 29 | 13 | 20 |

| East South Central | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 |

| West South Central | 15 | 20 | 6 | 11 |

| Mountain | 10 | 9 | 9 | 8 |

| Pacific | 12 | 8 | 14 | 8 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of Medicare Advantage (MA) and Medicare enrollment records.

Zero-premium plan members pay the Part B premium amount ($96.40 per month in 2011 for most beneficiaries) but pay no additional MA premiums.

Added-premium plan members pay the Part B premium and an extra premium to the MA plan.

Members with subsidies for only the Part B premium or Part D coverage.

There were no MA beneficiaries.

Some demographic characteristics varied across plan categories. Compared to added-premium plan members, zero-premium plan members were more likely to be black and reside in southern regions. Relative to the MA plan enrollees, dual SNP members were more likely to be female, younger than age sixty-five, and black.

Slightly more zero-premium plan members received a subsidy for the Medicare premium or Part D (12.5 percent) than added-premium plan enrollees (9.8 percent). As expected, most dual SNP enrollees (84 percent) had full Medicaid or Medicaid coverage of Medicare cost sharing. However, some dual SNP members had only limited subsidies (11.5 percent) or no subsidies (4.5 percent).20

PLAN CHARACTERISTICS

Enrollment in managed care models that restrict beneficiaries’ access to provider networks differed by premium level. Most zero-premium plan members (61 percent) and almost all dual SNPs enrollees (91 percent) belonged to health maintenance organization (HMO) MA plans that restrict provider networks (Exhibit 2, Appendix Exhibit A2).14 Only 40 percent of added-premium members belonged to HMO plans. Instead, added-premium members were more likely to be enrolled in local preferred provider organization plans (28 percent) that have less restrictive provider networks. MA beneficiaries in added-premium plans averaged $169 (interquartile range: $135–$194) in monthly premium costs. Almost all MA beneficiaries belonged to a plan that offered Part D coverage (94 percent, not shown).

EXHIBIT 2.

Coverage Features For Medicare Advantage Members, By Premium Level And Receipt Of Low-Income Subsidies, 2011

| Zero-premium plansa | Added-premium plansb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | With subsidiesc | All | With subsidiesc | |

| Mean plan premium (interquartile range) | $94 (96–96) | $94 (96–96) | $169 (135–194) | $157 (131–175) |

| Out-of-pocket limit meets CMS thresholds | ||||

| Meets voluntary threshold (up to $3,400) | 41% | 38% | 56% | 47% |

| Between thresholds ($3,401–$6,999) | 39 | 40 | 33 | 39 |

| At maximum threshold ($6,700) | 20 | 22 | 11 | 14 |

| Mean out-of-pocket limit (interquartile range) | $4,520 (3,400–5,000) | $4,575 (3,400–5,500) | $4,088 (3,400–5,000) | $4,373 (3,400–5,000) |

| Managed care model | ||||

| Health maintenance organization | 61% | 59% | 40% | 37% |

| Health maintenance organization–point of service | 17 | 19 | 11 | 8 |

| Local preferred provider organization | 7 | 6 | 28 | 25 |

| Private fee-for-service | 5 | 8 | 12 | 18 |

| Regional preferred provider organization | 11 | 8 | 8 | 13 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of Medicare Advantage (MA) and Medicare enrollment records.

NOTE CMS is Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Zero-premium plan members pay the Part B premium amount ($96.40 per month in 2011 for most beneficiaries) but pay no additional MA premiums.

Added-premium plan members pay the Part B premium and an extra premium to the MA plan.

Members with subsidies for only the Part B premium or Part D coverage.

OUT-OF-POCKET LIMITS

As mandated by CMS in 2011, all Medicare Advantage members had an out-of-pocket spending limit (Exhibit 2). Members of added-premium plans were more likely to have an out-of-pocket limit that met CMS’s lower, voluntary threshold of $3,400 (56 percent compared to 41 percent of zero-premium plan members). One in five zero-premium plan members had an out-of-pocket limit of $6,700, the maximum allowable. The majority of dual SNP members also had out-of-pocket expenses capped at $6,700 (Appendix Exhibit A2).14

Compared to all beneficiaries, beneficiaries with premium and Part D subsidies were slightly more likely to belong to plans with the maximum allowable out-of-pocket limit (22 percent versus 20 percent in zero-premium plans; 14 percent versus 11 percent in added-premium plans).

INPATIENT AND SKILLED NURSING FACILITY COST SHARING

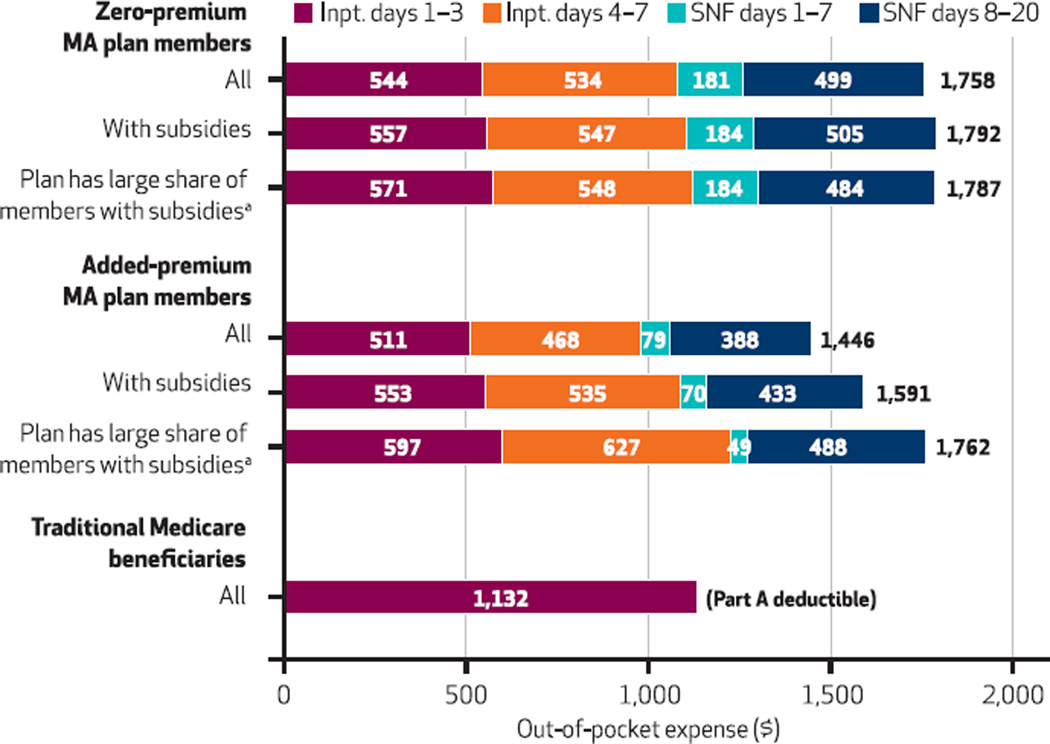

Zero-premium plan members had higher inpatient and SNF cost-sharing requirements than added-premium plan members. For seven inpatient days followed by twenty SNF days, zero-premium plan members would pay $1,758 out of pocket. Added-premium plan members averaged $1,466 in cost sharing for a similar episode (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3.

Expected Inpatient And Skilled Nursing Facility Out-Of-Pocket Expenses ($) For Medicare Advantage Members, By Premium Level And Receipt Of Subsidies, 2011

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of Medicare Advantage (MA) and Medicare enrollment records. NOTES Zero-premium plan members pay the Part B premium amount but pay no additional MA premiums. Added-premium plan members pay the Part B premium and an extra premium to the MA plan. Traditional Medicare beneficiaries may have additional Part B expenses for physician services while hospitalized. People with coinsurance as their primary form of cost sharing for inpatient or skilled nursing facility (SNF) services are excluded. Inpt. is inpatient. aMembers with subsidies for only the Part B premium or Part D coverage. Plans with a large share of members with subsidies are identified as follows: within each premium amount range, plans in the top quartile for percentage of members receiving subsidies for Part B premium or Part D coverage.

Zero-premium plan members’ higher SNF costs constitute most of this difference. Compared to added-premium plan members, zero-premium plan members’ mean expected SNF costs were 46 percent greater. Twenty days of SNF care would cost $680 for zero-premium plan members. In contrast, added-premium plan members would pay $467, on average.

Low-income MA beneficiaries receiving limited subsidies faced inpatient and SNF costs that were just as high as those for all MA beneficiaries. In fact, these members faced even greater costs in added-premium plans. Subsidized members in these plans had 10 percent more in combined inpatient and SNF out-of-pocket expenses than the average enrollee ($1,591 versus $1,446 for all added-premium enrollees; Exhibit 3). Members of added-premium plans with high shares of subsidized enrollees had even higher expenses for an inpatient and SNF episode ($1,762).

Dual SNP enrollees had lower cost-sharing amounts for inpatient and SNF care than other MA enrollees (Appendix Exhibit A3).14 Depending on what Medicaid cost-sharing requirements apply to enrollees, dual SNP members had mean expected expenses that were close to zero or $397 for an inpatient and SNF stay.

In comparison, the traditional Medicare program had a $1,132 deductible for inpatient care in 2011.Nocost sharing was required for the first twenty days of an SNF stay, as long as it was preceded by a three-day hospitalization. Beneficiaries who had supplemental coverage might not have paid any of the deductible amount out of pocket. Traditional Medicare beneficiaries may have additional Part B costs for physician services while hospitalized.

CHANGES IN OUT-OF-POCKET LIMITS AND COST SHARING

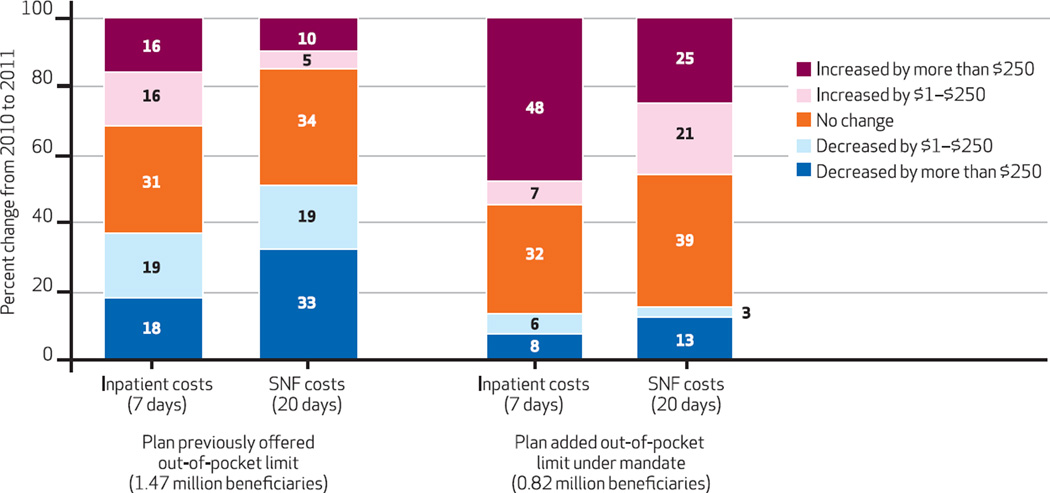

Medicare Advantage benefit changes from 2010 to 2011 demonstrate a trade-off between capping overall spending and limiting first-dollar cost sharing. We identified 2.29 million MA beneficiaries who belonged to the same zero-premium plan in 2010 and 2011. About 36 percent of these beneficiaries did not have an out-of-pocket limit in 2010. All members of private fee-for-service plans and, because of earlier CMS requirements, regional preferred provider organization plans had out-of-pocket limits prior to 2011. Notably, beneficiaries without spending caps had much lower expected expenses in 2010 for seven inpatient days followed by twenty SNF days ($1,150 versus $2,069 for beneficiaries in plans with an out-of-pocket limit; data not shown).

Exhibit 4 shows that beneficiaries who gained an out-of-pocket limit in 2011 under the new CMS mandate were more likely than others to have increases in inpatient and SNF cost sharing from 2010 to 2011. Almost half (48 percent) of zero-premium plan members with a new out-of-pocket limit had at least a $250 increase in expected costs for seven inpatient days. In contrast, only 16 percent of plan members who already had an out-of-pocket limit in 2010 had an inpatient cost-sharing increase greater than $250 in 2011. The relationship is similar for SNF costs: Zero-premium plan members who gained an out-of-pocket limit under the 2011 mandate were more likely than others to see an increase in twenty-day SNF costs (21 percent had an increase up to $250, 25 percent had an increase greater than $250). Decreases in SNF cost sharing were more common among zero-premium plan members with previous out-of-pocket limits (33 percent had at least a $250 drop in SNF cost sharing) compared to those with no previous limit. Appendix Exhibit A4 presents these results by region and plan type.14

Exhibit 4.

Changes From 2010 To 2011 In Inpatient And Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) Costs For Zero-Premium Plan Members By The Addition Of An Out-Of-Pocket Limit Under The 2011 Mandate

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of Medicare Advantage and Medicare enrollment records. NOTE Analysis limited to members enrolled in the same zero-premium plan for both 2010 and 2011.

As a result of these trends, zero-premium plan members who gained an out-of-pocket limit had their average expected costs for an inpatient SNF care episode increase to $1,443. In contrast, these costs decreased to $1,817 in 2011 for members who already had an out-of-pocket limit (data not shown).

Discussion

In this national study we found that approximately half of 2011 Medicare Advantage members were enrolled in zero-premium plans and averaged $1,758 in expected out-of-pocket expenses for seven inpatient days followed by twenty skilled nursing facility days. Low-income beneficiaries with premium and Part D subsidies had expected out-of-pocket expenses that were similar to or greater than the average across all enrollees within the same premium category. About a third of zero-premium plan members who stayed in the same plan in 2010 and 2011 gained an out-of-pocket limit when CMS began requiring all MA plans to offer this benefit. However, these beneficiaries were also more likely to experience an increase in inpatient and SNF cost sharing compared to beneficiaries that already had an out-of-pocket limit.

There is limited evidence to predict how Medicare beneficiaries respond to inpatient and SNF cost sharing, and whether there may be adverse unintended consequences. Previous studies have found that patients, including Medicare beneficiaries, decrease their use of both necessary and unnecessary care in response to increased cost sharing.21–24 Cost sharing for critical services may contribute to plan disenrollment: People who leave MA plans are more likely to have greater health service use and report poorer health than people who stay in MA plans.25

Our study has three main implications for policy makers. First, MA beneficiaries still pay a great deal for inpatient and SNF services even after new regulations have gone into effect. We found that these expenses often exceed what traditional Medicare beneficiaries without supplemental coverage would pay under the Part A deductible, which covers hospitalizations and SNF services. The majority of MA beneficiaries are enrolled in zero-premium plans with higher cost-sharing expectations. This pattern could reflect other studies’ findings that Medicare beneficiaries are strongly influenced by premium levels and have trouble selecting plans that will minimize their out-of-pocket exposure.26–28 It is not clear why dual Special Needs Plan members had lower expected inpatient and SNF costs than members of non-SNPs. One possibility is that these benefit features are attractive to the specialized populations targeted by dual SNPs. State Medicaid programs may also influence benefits in some dual SNPs.

Second, the combination of capping overall spending and restricting cost sharing for specific services produced potentially conflicting effects on expected out-of-pocket spending. MA enrollees who gained an out-of-pocket limit in 2011 were also more likely to see increases in their inpatient and SNF cost sharing relative to MA enrollees whose plans offered spending caps prior to 2011. An overall out-of-pocket limit has the important advantage of limiting beneficiaries’ exposure to costs regardless of how those costs are incurred. Requiring all MA plans to have out-of-pocket limits may also make it easier for beneficiaries to compare plans on other dimensions, such as premiums and cost-sharing requirements.

However, if an out-of-pocket limit results in greater first-dollar cost sharing, beneficiaries, especially those with few financial resources, may experience reduced access to services. Compared to people with limited savings, an out-of-pocket limit could disproportionately benefit MA members with more assets to protect. It is unclear whether the number of beneficiaries exposed to higher inpatient and SNF out-of-pocket expenses exceeds the number of beneficiaries who would benefit from reaching a spending cap. Our study did not evaluate the comparative effectiveness of instituting an out-of-pocket limit versus restricting cost sharing for specific services on beneficiaries’ access and clinical outcomes.

Finally, our results show that low-income MA beneficiaries have expenses that are as high as those of other beneficiaries. For a single individual with the maximum amount of allowable resources for the Part D low-income subsidy program (150 percent of poverty and $11,140 in assets) in a zero-premium plan, the average cost of a combined inpatient and SNF episode would have consumed 1.29 months of income or 16 percent of assets.29 The Part A deductible for the same episode in traditional Medicare would consume 0.83 months of income or 10 percent of assets. This finding is troubling given the likely limited ability for such beneficiaries to afford an out-of-pocket expense of this magnitude. Low-income MA and traditional Medicare beneficiaries have greater access to financial assistance for high prescription drug costs than assistance for large and unpredictable out-of-pocket expenses for acute inpatient and postacute SNF services. Policy makers should consider solutions that address low-income beneficiaries’ spending across all services.

Conclusion

Medicare Advantage enrollees, including low-income beneficiaries who receive needs-based subsidies, face substantial out-of-pocket expenses for an acute and postacute episode of care. Our study suggests that federal policy makers should address low-income beneficiaries’ ability to afford inpatient and skilled nursing facility care and should continue monitoring whether or not current regulations protect beneficiaries from high spending for these services.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institute on Aging (Grant Nos. P01 AG-027296 and R01 AG-044374). Amal Trivedi reports consulting for the Merck Manual. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this research was presented as a poster at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting in San Diego, California, June 2014.

Contributor Information

Laura M. Keohane, Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice at the School of Public Health, Brown University, in Providence, Rhode Island.

Regina C. Grebla, School of Public Health at Brown University and associate director in the Global Health Economics, Outcomes Research, and Epidemiology Division at Shire in Lexington, Massachusetts.

Vincent Mor, Community Health in the Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice at the School of Public Health, Brown University, and a research health scientist at the Providence Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center.

Amal N. Trivedi, Email: amal_trivedi@brown.edu, Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice at the School of Public Health, Brown University, and an investigator in the Center of Innovation in Long-Term Services and Supports, Providence VA Medical Center.

NOTES

- 1.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Washington (DC): MedPAC; 2004. Dec, [cited 2015 Apr 15]. Benefit design and cost sharing in Medicare Advantage plans [Internet] Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/reports/Dec04_CostSharing.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gold M, Hudson M, Jacobson G, Neuman T. Medicare Advantage 2010 data spotlight: benefits and cost-sharing [Internet] Menlo Park (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010. Feb, [cited 2015 Apr 15]. Available from: http://kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-2010-data-spotlight-benefits-and/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gold M. Medicare Advantage—lessons for Medicare’s future. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(13):1174–1177. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1200156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman R, Dowd B, Wrobel M. Risk selection and benefits in the Medicare+Choice program. Health Care Financ Rev. 2003;25(1):23–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper AL, Trivedi AN. Fitness memberships and favorable selection in Medicare Advantage plans. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(2):150–157. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1104273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare program; policy and technical changes to the Medicare Advantage and Medicare prescription drug benefit programs; final rule. Federal Register [serial online] [cited 2015 Apr 15];2010 Apr 15; Available from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2010-04-15/pdf/2010-7966.pdf. [PubMed]

- 7.Moon DR. Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2010. Apr 16, [cited 2015 Apr 15]. Benefits policy and operations guidance regarding bid submissions; duplicative and low enrollment plans; cost sharing standards; general benefits policy issues; plan benefits package (PBP) reminders for contract year (CY) 2011 [Internet] Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/HealthPlansGenInfo/downloads/dfb_policymemo041610final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Chapter 4. Washington (DC): MACPAC; 2013. Mar, [cited 2015 Apr 15]. Report to the Congress on Medicaid and CHIP [Internet] Medicaid coverage of premiums and cost sharing for low-income Medicare beneficiaries; Available from: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Medicaid_Coverage_of_Premiums_and_Cost_Sharing_for_Low-Income_Medicare_Beneficiaries.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Social Security Administration. Washington (DC): SSA; 2014. Dec, [cited 2015 Apr 15]. Program operations manual system (POMS): HI 03030.025 resource limits for subsidy eligibility [Internet] Available from: https://secure.ssa.gov/poms.nsf/lnx/0603030025. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briesacher BA, Ross-Degnan D, Wagner AK, Fouayzi H, Zhang F, Gurwitz JH, et al. Out-of-pocket burden of health care spending and the adequacy of the Medicare Part D low-income subsidy. Med Care. 2010;48(6):503–509. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181dbd8d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moon DR, Tudor CG. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2011. Aug 8, [cited 2015 Apr 15]. 2012 HEDIS, HOS, and CAHPS measures for reporting by Medicare Advantage and other organization types [Internet] Available from: https://www.healthypeopleteam.com/CMS%20HEDIS%20Memo.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Baltimore (MD): CMS; [cited 2015 Apr 22]. Monthly enrollment by plan—December 2011 [Internet] Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MCRAdvPartDEnrolData/Monthly-Enrollment-by-Plan-Items/CMS1254807.html. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Baltimore (MD): CMS; [cited 2015 Apr 15]. SNP comprehensive report—December 2011 [Internet] Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MCRAdvPartDEnrolData/Special-Needs-Plan-SNP-Data-Items/CMS1254864.html. [Google Scholar]

- 14.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 15.Social Security Administration. Washington (DC): SSA; 2012. Feb, [cited 2015 Apr 15]. Annual statistical supplement, 2011 [Internet] Table 2.CI: Medicare cost sharing and premium amounts, 1966–2012; Available from: http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2011/2b-2c.html#table2.c1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh EG, Clark WD. Managed care and dually eligible beneficiaries: challenges in coordination. Health Care Financ Rev. 2002;24(1):63–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Congressional Budget Office. Washington (DC): CBO; 2004. Jul, [cited 2015 Apr 15]. A detailed description of CBO’s cost estimate for the Medicare prescription drug benefit [Internet] Available from: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/56xx/doc5668/07-21-medicare.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shoemaker JS, Davidoff AJ, Stuart B, Zuckerman IH, Onukwugha E, Powers C. Eligibility and take-up of the Medicare Part D low-income subsidy. Inquiry. 2012;49(3):214–230. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_49.03.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gold M, Jacobson G, Damico A, Neuman P. Medicare Advantage 2014 spotlight: enrollment market update [Internet] Menlo Park (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2014. May 1, [cited 2015 Apr 15]. Available from: http://kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-2014-spotlight-enrollment-market-update/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.These beneficiaries may have joined a dual Special Needs Plan (SNP) after acquiring Medicaid coverage during the year. However, the distribution of levels of financial support was similar among members with a full year of dual SNP enrollment.

- 21.Manning WG, Newhouse JP, Duan N, Keeler EB, Leibowitz A, Marquis MS. Health insurance and the demand for medical care: evidence from a randomized experiment. Am Econ Rev. 1987;77(3):251–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trivedi AN, Moloo H, Mor V. Increased ambulatory care copayments and hospitalizations among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(4):320–328. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0904533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandra A, Gruber J, McKnight R. Patient cost-sharing and hospitalization offsets in the elderly. Am Econ Rev. 2010;100(1):193–213. doi: 10.1257/aer.100.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trivedi AN, Rakowski W, Ayanian JZ. Effect of cost sharing on screening mammography in Medicare health plans. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(4):375–383. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa070929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McWilliams JM, Hsu J, Newhouse JP. New risk-adjustment system was associated with reduced favorable selection in Medicare Advantage. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(12):2630–2640. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abaluck J, Gruber J. Choice inconsistencies among the elderly: evidence from plan choice in the Medicare Part D program. Am Econ Rev. 2011;101(4):1180–1210. doi: 10.1257/aer.101.4.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atherly A, Dowd BE, Feldman R. The effect of benefits, premiums, and health risk on health plan choice in the Medicare program. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):847–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McWilliams JM, Afendulis CC, McGuire TG, Landon BE. Complex Medicare Advantage choices may overwhelm seniors—especially those with impaired decision making. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(9):1786–1794. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Washington (DC): HHS; [updated 2012 Feb 2; cited 2015 Apr 15]. The federal poverty level for an individual in 2011 was $10,890. Department of Health and Human Services. The 2011 HHS poverty guidelines [Internet] Available from: http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/11poverty.shtml. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.