Abstract

Pulmonary tumour thrombotic microangiopathy (PTTM) is a rapidly progressive pulmonary disease that is a fatal complication of malignancy. It manifests clinically as subacute respiratory failure with pulmonary hypertension, progressive right sided heart failure, and sudden death. We describe here a case of PTTM associated with occult metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach. Although rare, PTTM needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of dyspnoea of unknown origin, particularly in patients with respiratory failure and also pulmonary hypertension, and in patients were there is no improvement in respiratory symptoms with steroid therapy.

Keywords: Pulmonary tumour thrombotic microangiopathy, Gastric cancer, Oncology, Interstitial lung disease

Introduction

Pulmonary tumour thrombotic microangiopathy (PTTM), first defined by Von Herbay et al., in 1990, is known as a rare but fatal pulmonary complication associated with various malignancies [1]. However, cases of tumour cells embolising to the pulmonary vasculature have been described in the literature as early as 1930 [2]. This condition manifests as subacute respiratory failure with pulmonary hypertension, rapidly progressive right sided heart failure, and sudden death [3], [4]. Histopathologically it is characterised by diffuse intimal myofibroblast proliferation in pulmonary blood vessels, accompanied by multiple microthrombi, which result from invasion of the pulmonary vasculature by cancer cells [1], [3]. The primary malignancy is often poorly differentiated gastric adenocarcinoma, including signet ring cell carcinoma but it has also been described in other upper GI malignancies as well as breast and lung carcinoma [1], [5]. The pathophysiology of this debilitating condition remains obscure.

We describe here a case of pulmonary tumour thrombotic microangiopathy associated with occult metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach.

Case report

A 41 year old male, life-long non-smoker, initially presented with a 2 week history of worsening shortness of breath and dry cough. Prior to admission he had been treated in the community for a presumed atypical pneumonia with amoxicillin and clarithromycin. No specific symptoms related to the gastrointestinal system were reported at this time. No significant past medical history was noted. He was on no regular medication. There was a family history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in his father. He worked as a long distance lorry driver and had no occupational dust or chemical exposure. On clinical examination he was found to be haemodynamically stable and apyrexic with oxygen saturations of 91% on inspiring room air. Auscultation of the chest revealed normal breath sounds with fine crepitations throughout the lung fields. No other abnormal focal examination findings were identified.

Initial investigations: haemoglobin 158 g/L (115–165 g/L), white blood cell count 10 × 109/L (4–10 × 109/L), platelet count 328 × 109 (150–450 × 109/L), and C reactive protein 22.3 mg/L (1–5 mg/L). Liver and renal function tests were normal. Prothrombin time was 12.1s (9.3–11.8s), APTT was 27.2s (23.4–32.4s), Fibrinogen 4.08 g/L (1.9–4.0 g/L) and D-dimer was 13 units (0.01–0.5 units). Arterial blood gas demonstrated patient to have type I respiratory failure (pO2 7.68 kPa). Chest radiograph demonstrated areas of widespread scattered patchy consolidation and reticulonodular interstitial changes. An initial diagnosis of interstitial or organizing pneumonia secondary to an atypical organism was made. The patient was commenced on intravenous piperacillin with tazobactam, and also intravenous clarithromycin, as well as receiving oral steroids, regular nebulisers, and oxygen therapy pending further investigation.

Legionella and pneumococcal urinary antigens were negative. HIV, CMV, ANCA, anti-GBM antibodies, and Rheumatoid Factor were all negative. Immunoglobulins were within the normal range including IgG subclasses. ACE level was normal (<10). Extrinisic allergic alveolitis screen was negative, IgG to Aspergillus was normal as was total IgE. Respiratory syncytial virus was positive in sputum. Influenza viruses A and B, and Pneumocystis jiroveci, B.pertussis, and Chlamydia psittaci PCR were negative.

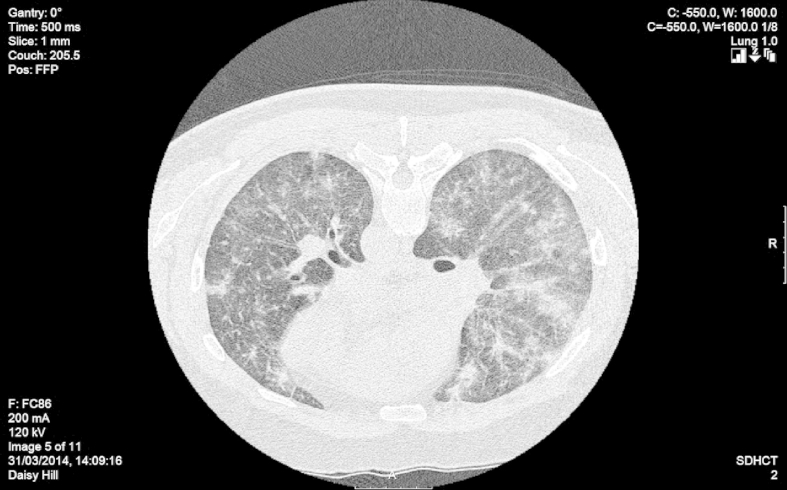

A high-resolution CT scan was carried out which demonstrated reticular nodular interstitial change with alveolar infiltrates and thickening of the secondary pulmonary lobule. No obvious lymphadenopathy or bronchovascular beading was noted. A small pericardial effusion was noted (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CT image showing alveolar infiltrates and reticular nodular opacities.

The patient initially improved on antibiotic and steroid therapy however he remained hypoxic and further investigation was undertaken.

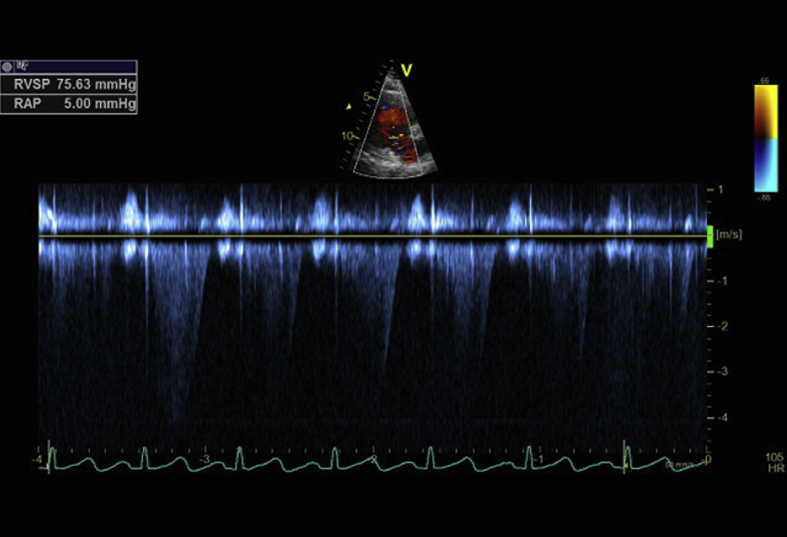

Echocardiography demonstrated a right ventricular systolic pressure of 75 mmHg, and the right atrium and right ventricle to be mildly enlarged. A paradoxical motion of the ventricular septum was noted, as well as flattening of the ventricular septum in systole consistent with right ventricular pressure overload. Overall left ventricular function was normal (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Echocardiography demonstrating elevated right ventricular systolic pressure as estimated from the tricuspid regurgitation signal.

Bronchoscopy demonstrated no endobronchial mucosal abnormality but thick orange jelly like secretions were observed. Cytology demonstrated a prominent mononuclear inflammatory component with numerous degenerate bronchial epithelial cells. Occasional atypical cells with prominent nucleoli were noted, which were thought to be reactive pneumocytes. Biopsy either endobronchial or transbronchial was not possible due to hypoxia worsening during the procedure. Culture of bronchial secretions demonstrated E.coli sensitive to meropenem.

The patient improved with a change in antibiotic therapy but subsequently deteriorated. On day 19 he developed acute unilateral visual loss which on ophthalmological review was retinal vein thrombosis attributed to steroid use. He became increasingly short of breath over the next 2 days and his WCC and platelet count began to fall precipitously. On day 24 he developed frank haemoptysis, type 1 respiratory failure and respiratory distress requiring intubation and ventilation. At time of referral to ICU for ventilatory support, he had become acutely pancytopenic with associated coagulopathy and newly deranged LFTs. Haemoglobin was 114 g/L(115–165 g/L), platelet count was 30 having dropped from 328 initially on admission (150–450 × 109/L), white blood cell count 3 × 109/L(4–10 × 109/L), neutrophils 35%. Prothrombin time was 15.8s (9.3–11.8s), APTT was 31.7s (23.4–32.4s), and Fibrinogen 1.04 g/L (decreased from 4.8 g/L) (1.9–4.0 g/L) and D-dimer was 47.3 units (0.01–0.5units).

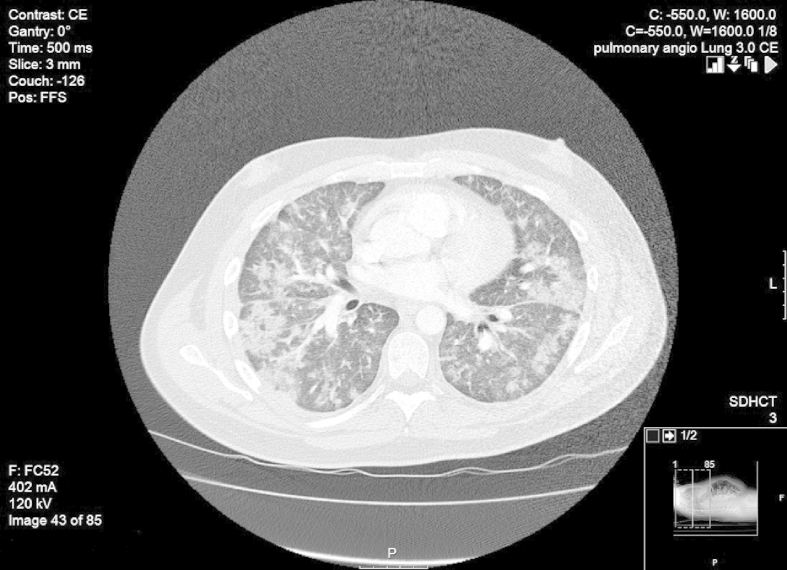

Repeat CT Chest, Abdomen and Pelvis at this time demonstrated increased bilateral pulmonary infiltrates but no thoracic lymphadenopathy, or intra-thoracic or intra-abdominal mass and no evidence of pulmonary embolus (Fig. 3). One small celiac axis node was noted to be 1.5 cm. The working diagnosis remained an inflammatory interstitial process with blood dyscrasia attributed initially to antimicrobial therapy.

Fig. 3.

CT showing progression of infiltrates to confluent consolidation.

Upon transfer to ICU he was treated with IV Methylprednisolone, IV Immunoglobulins, FFP and platelet transfusions. Given his acute pancytopenia, he underwent bone marrow aspiration & trephine biopsy, which showed a significant infiltrative process with evidence of adenocarcinomatous cells, with signet ring cells.

The patient was discussed with the acute oncologist and at the gastrointestinal multidisciplinary meeting and given his given his current clinical state, and with tissue diagnosis found in bone marrow of metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma of likely gastric origin, it was deemed inappropriate to consider any form of chemotherapy but rather refer the patient to the palliative care team. The patient was extubated and passed away sadly on the same day. The patients' family declined post-mortem.

Discussion

PTTM is an uncommon complication in individuals with metastatic cancer. It is predominantly diagnosed post-mortem and Von Herbay found in a retrospective study examining the autopsy findings of 630 patients with metastatic carcinoma, that PTTM was observed in 3.3% of cases, and of these cases, 90% were associated with gastric adenocarcinoma [1]. Antemortem diagnosis is extremely challenging due to the rapid development of lethal pulmonary hypertension, heart failure and death. In this case the definitive investigation would have been a lung biopsy but his degree of hypoxia precluded this.

PTTM should be suspected in patients with dyspnoea of unknown origin, particularly in patients with a history of mucin-secreting adenocarcinoma. It presents in a similar fashion to respiratory diseases such as pulmonary thromboembolism, pulmonary hypertension, or pneumonia. Typically there is evidence of metastatic disease at the time of presentation [6], but occult cancer manifested as pulmonary thrombotic microangiopathy is more rarely reported, as in this case.

PTTM is characterised by fibrocellular intimal proliferation and focal hypercoagulability, which together result in pulmonary artery stenosis or obstruction, and consequently the patient develops severe dyspnoea and pulmonary hypertension. Approximately half of cases are complicated by disseminated intravascular coagulation [7], as happened in this current case when the patient acutely deteriorated requiring ventilatory support.

No treatment was administered in this current case, due to the patients' rapid deterioration and clinical condition upon diagnosis, but if detected early enough, chemotherapy is believed to reduce the burden of tumour cells in PTTM, and thereby lessen the stimulus for intimal proliferation. Whilst no definite treatment had been established, it is perceived chemotherapy may prolong the survival period. Evidence also suggests serotonin antagonists may be beneficial by blocking the pathways leading to intimal fibrocellular proliferation [5], [8].

In conclusion, clinically PTTM is a rapidly progressive pulmonary disease that is a fatal complication of malignancy and is associated with a poor prognosis. It represents an important differential diagnosis of dyspnoea of unknown origin, particularly in patients with respiratory failure and also pulmonary hypertension. In summary, it is important to suspect PTTM as a differential diagnosis for rapidly worsening respiratory conditions particularly if there is no improvement with steroid therapy, not only in patients with cancer, but also in patients without a cancer history, as the early diagnosis may prolong the survival period of PTTM patients.

References

- 1.Von Herbay A., Illes A., Waldherr R., Otto H.F. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy with pulmonary hypertension. Cancer. 1990;66:587–592. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900801)66:3<587::aid-cncr2820660330>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes J.E. A case of hydatidiform mole with multiple small syncytial infarctions of the lungs. Proc Roy Soc Med. 1930;23:1157–1159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chinen K., Tokuda Y., Fujiwara M., Fujioka Y. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy in patients with gastric carcinoma: an analysis of 6 autopsy cases and review of the literature. Pathol Res Pract. 2010;206:682–689. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakashita N., Yokose C., Fujii K., Matsumoto M., Ohnishi K., Takeya M. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy resulting from metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach. Pathol Int. 2007;57:383–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2007.02111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi F., Kumasaka T., Nagaoka T., Wakiya M., Fujii H., Shimizut K. Osteopontin expression in pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy caused by gastric carcinoma. Pathol Int. 2009;59:752–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandalyia R., Farhat S., Uprety D., Balla M., Gandhi A., Goldhahn R. Occult gastric cancer presenting as hypoxia from pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy. J. Gastric Cancer. 2014;14(2):142–146. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2014.14.2.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kagata Y., Nakanishi K., Ozeki Y., Terahata S., Matsubara O. An immunohistochemical study of tumor thrombotic microangiopathy:the role of TF, FGF and VEGF. J Jpn Coll Angiol. 2003;43:679–684. [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacLean M.R. Pulmonary hypertension and the serotonin hypothesis: where are we now? Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:27–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]