Abstract

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) plays a central role in regulating energy homeostasis, and may provide novel strategies for the treatment of human obesity. BAT-mediated thermogenesis is regulated by mitochondrial uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) in classical brown and ectopic beige adipocytes, and is controlled by sympathetic nervous system (SNS). Previous work indicated that fish oil intake reduces fat accumulation and induces UCP1 expression in BAT; however, the detailed mechanism of this effect remains unclear. In this study, we investigated the effect of fish oil on energy expenditure and the SNS. Fish oil intake increased oxygen consumption and rectal temperature, with concomitant upregulation of UCP1 and the β3 adrenergic receptor (β3AR), two markers of beige adipocytes, in the interscapular BAT and inguinal white adipose tissue (WAT). Additionally, fish oil intake increased the elimination of urinary catecholamines and the noradrenaline (NA) turnover rate in interscapular BAT and inguinal WAT. Furthermore, the effects of fish oil on SNS-mediated energy expenditure were abolished in transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) knockout mice. In conclusion, fish oil intake can induce UCP1 expression in classical brown and beige adipocytes via the SNS, thereby attenuating fat accumulation and ameliorating lipid metabolism.

Fish oil, regarded as a healthy addition to the diet of diabetic patients1, contains the fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). These fatty acids, which are abundant in fish, have hypolipidaemic effects, augment the efficacy of the lipid-lowering drugs2, reduce cardiac events3, and inhibit the progression of atherosclerosis4. Numerous animal studies have demonstrated that fish oil reduces the accumulation of body fat, which could be mediated via several possible mechanisms, including reduced proliferation of fat cells5, and metabolic changes in the liver6, adipose tissue7, and small intestines8. Furthermore, fish oil supplementation prevents fat accumulation in white adipose tissue (WAT), compared to other dietary oils9.

Most mammals maintain body temperature by increasing heat production in response to cold. This process, termed adaptive thermogenesis, is achieved by shivering. Alternatively, humans and other small animals can increase energy expenditure via uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation in brown adipose tissue (BAT) of the interscapular region by BAT-specific uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) in the mitochondria10,11,12. BAT-mediated thermogenesis is activated by the hypothalamus via the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). Increased noradrenaline (NA) release enhances cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels to rapidly activate lipolysis, thereby initiating mitochondrial heat production and synergistically increasing energy expenditure13,14,15. In contrast, WAT accumulates excess energy as triglycerides (TG), and primarily regulates energy storage.

Recent developments have demonstrated that brown adipocyte-like adipocytes, termed beige adipocytes, are found in the WAT, including the inguinal WAT of rodents and humans16,17,18,19,20. These adipocytes have a multilocular morphology and are UCP1-positive21. Furthermore, beige adipocytes are induced in response to cold exposure or prolonged β adrenergic stimulation22. Traditionally, WAT has been regarded as an organ for energy storage; however, a recent study indicated that activation of the SNS in WAT may regulate fat mobilization to maintain energy supplies23.

Dietary factors regulating brown and beige adipocyte development and function were identified in WAT. Many reports suggest that transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) is activated by a wide range of chemical materials, including some lipids24,25,26. Recently, capsinoids, a group of capsaicin analogues, were shown to activate gastrointestinal TRPV1 and induce BAT thermogenesis in humans and rodents27. Furthermore, TRPV1 agonists found in foods, such as fish oil, could regulate TRPV1 in the gastrointestinal tract28,29.

In this study, we investigated the effect of fish oil intake on energy metabolism. Fish oil intake reduced body weight gain and fat accumulation, while increasing oxygen consumption and rectal temperature, as compared to control diet-fed mice. Furthermore, fish oil intake induced UCP1 expression in both of BAT and WAT, and activated the SNS. Combined, our data indicate that fish oil intake enhances energy utilization by inducing UCP1 in both BAT and WAT, and could thereby prevent obesity and related metabolic disorders.

Results

Effects of fish oil on body weight

We evaluated the effect of fish oil on the accumulation of body fat in mice. Mice fed fish oil gained significantly less weight than mice fed a control diet (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, the abdominal adipose tissue weight was lower in fish oil treated mice than control mice (Fig. 1B and supplemental table 1). These data suggested fish oil intake increased energy expenditure. Fasting glucose, insulin, TG and leptin levels in the mice fed fish oil were lower than mice fed the control diet (Supplemental table 2). Additionally, the plasma adiponectin concentration was significantly higher in mice fed fish oil (Supplemental table 2). Taken together, fish oil intake decreased body weight and abdominal tissue weight, and protected against diet-induced obesity.

Figure 1. Fish oil intake reduced body weight gain and fat accumulation.

Fish oil intake decreased body weight (A) and abdominal WAT (B) gain in mice. Mice were fed a control diet (C), control diet containing low-dose DHA-enriched fish oil (LD), control diet containing high-dose DHA-enriched fish oil (HD), control diet containing low-dose EPA-enriched fish oil (LE), and control diet containing high-dose EPA-enriched fish oil (HE) for 10 weeks. Fish oil intake increased oxygen consumption (C) and rectal temperature (D). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 7–8 animals per group. Different letters indicate significant differences between groups.

Effect of fish oil on energy expenditure

To investigate how fish oil affected energy expenditure, indirect calorimetry was performed by measure oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production. Oxygen consumption was significantly increased by fish oil intake, as compared to control diet intake, over a 20 h period (Fig. 1C). There was no statistically significant difference in respiratory quotient (RQ) between all groups (C; 0.86 ± 0.02, LD; 0.86 ± 0.02, HD; 0.88 ± 0.01, LE; 0.88 ± 0.01, HE; 0.88 ± 0.02). Furthermore, rectal temperature was significantly increased by fish oil intake (Fig. 1D). Consistent with the higher oxygen consumption and rectal temperature, the mice fed fish oil displayed enhanced energy expenditure. These results indicate that fish oil intake enhanced thermogenesis.

Effect of fish oil on thermogenesis-associated gene expression

We next examined the effects of fish oil on BAT gene and protein expression. UCP1 mRNA and protein expression in interscapular BAT was significantly induced by fish oil intake (Fig. 2A,C). Moreover, UCP1 mRNA and protein expression was also enhanced in the inguinal WAT (Fig. 2B,D). These UCP1-positive adipocytes were considered to be beige adipocytes. In addition, the expression of beige adipocyte marker genes, including peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1 α (Pgc1α), carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 B (Cpt1b), cell death-inducing DFFA-like effector A (Cidea), PR domain containing 16 (Prdm16), and fibroblast growth factor 21 (Fgf21), was enhanced in interscapular BAT and inguinal WAT of mice fed fish oil (Fig. 2E). Interestingly, T-box transcription factor 1 (Tbx1), recently defined as a marker of beige adipocytes, was significantly induced in inguinal WAT by fish oil (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2. Fish oil intake induced UCP1 expression in interscapular BAT and inguinal WAT.

Fish oil intake induced UCP1 protein expression in interscapular BAT (A) and inguinal WAT (B). Fish oil intake also induced UCP1 mRNA expression in interscapular BAT (C) and inguinal WAT (D). Fish oil intake induced beige adipocyte-specific gene expression in interscapular BAT (E) and inguinal WAT (F). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 7–8 animals per group. Different letters indicate significant differences between groups.

Effect of fish oil on the SNS

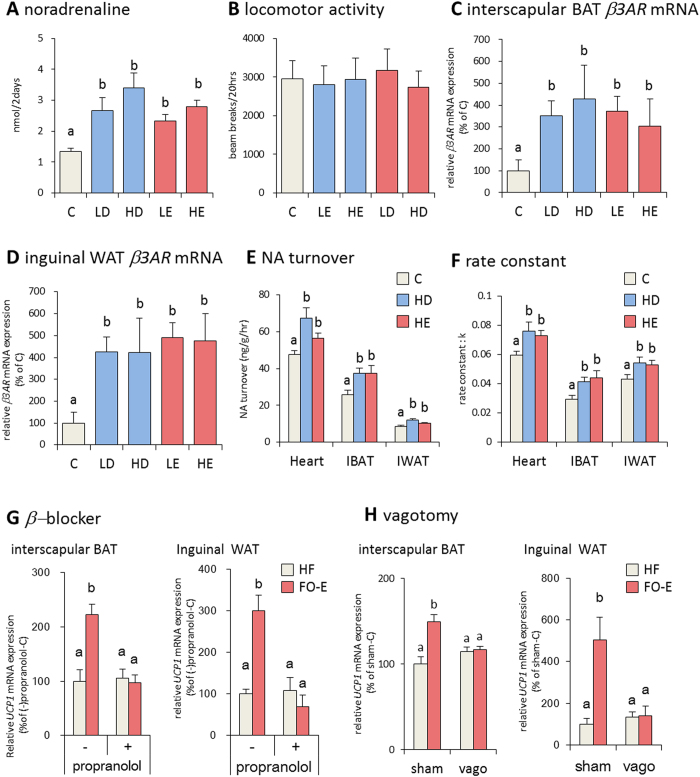

BAT activity is primarily regulated by the SNS, through the binding of NA to the β adrenergic receptors, thereby inducing lipolysis and the activation of UCP1 to enhance thermogenesis. Thus, we next examined the effects of fish oil intake on the release of catecholamines in mice. The amount of NA in urine was significantly increased by fish oil intake (Fig. 3A). Additionally, we recorded spontaneous locomotor activity, and found that it was not altered by fish oil (Fig. 3B). The β3 adrenergic receptor (β3AR) activation contributes to thermoregulation and energy homeostasis via sympathetic stimulation of BAT adaptive thermogenesis. Therefore, we evaluated the effects of fish oil on β3AR expression. β3AR mRNA was significantly induced in interscapular BAT and inguinal WAT of mice fed fish oil, as compared to mice fed the control diet (Fig. 3C,D), and the histological analysis revealed clusters of multiocular cells with UCP1 expression (Supplemental Fig. 1). Furthermore, fish oil intake significantly enhanced the turnover of NA and rate constant in interscalupar BAT and inguinal WAT (Fig. 3E,F), suggesting that fish oil intake increased sympathetic outflow.

Figure 3. Fish oil intake induced SNS activation.

Fish oil intake increased the amount of noradrenaline (A) in the urine. Urine was collected form mice housed in metabolic cages as described in the methods. Fish oil intake does not change total locomotor activity (B), after 20 h. Fish oil intake induced β3AR mRNA expression in interscapular BAT (C) and inguinal WAT (D). Effects of fish oil intake on NA turnover (E) and rate constant (F) in the heart, interscapular BAT, and inguinal WAT. Effects of propranolol on fish oil intake-induced changes of UCP1 expression levels in interscapular BAT(G left) and inguinal WAT (G right). Effects of fish oil on UCP1 expression levels in sham-operated (sham) and vagotomized (sham) mice (H left; interscapular BAT, (H) right; inguinal WAT). Mice were fed a control diet, and received oral administration of Mineral oil (HF) or EPA-enriched fish oil (FO-E). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 7–8 animals per group. Different letters indicate significant differences between groups.

The increased expression of β3AR, UCP1, and beige adipocyte marker genes suggested that fish oil intake caused adipose tissues to activate the SNS. To determine the direct influence of fish oil activation in the SNS, we examined the effects of fish oil intake on the β adrenergic blocker, propranolol. After treatment with propranolol, fish oil intake did not affect upregulation of UCP1 mRNA expression in interscapular BAT and inguinal WAT (Fig. 3G). Furthermore, upregulation of UCP1 mRNA expression by fish oil intake was blocked by subdiaphragmatic vagotomy (Fig. 3H).

Effect of fish oil on energy expenditure in TRPV1 knockout mice

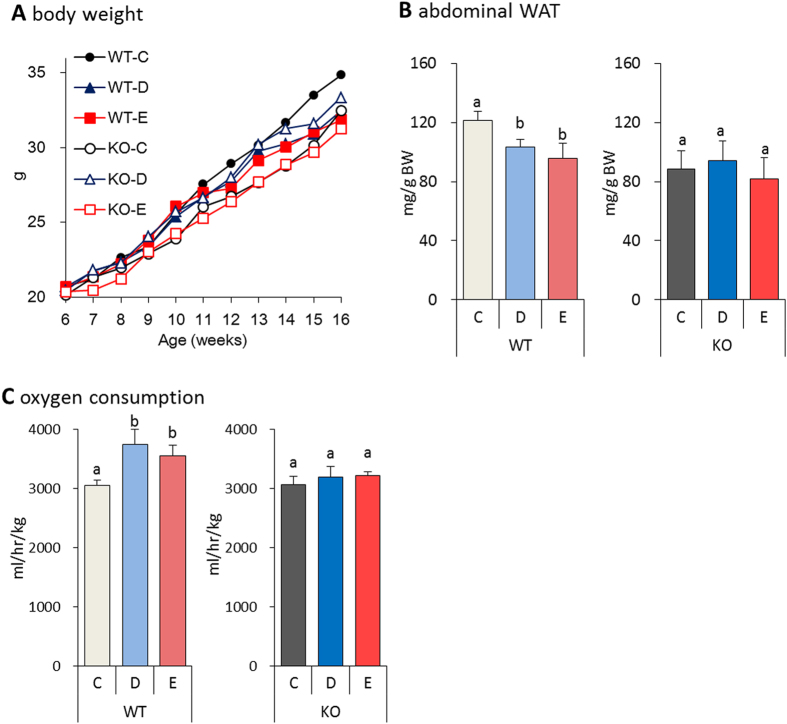

According to previous studies, capsaicin and capsinoids, increase energy expenditure and reduce body fat, suggesting that TRPV1 may play a role in thermogenesis. Interestingly, dietary factors can also activate TRPV1. Stimulation of TRPV1 is known to activate the SNS30,31. However, how TRPV1 activates the SNS remains unclear. To better understand the role of TRPV1, we explored the effects of fish oil intake in wild-type (WT) mice and TRPV1 knockout (KO) mice. We examined changes in body weight of WT and TRPV1 KO mice consuming either a control diet or fish oil diet. In the TRPV1 KO mice fed fish oil, no difference in body weight gain and abdominal WAT accumulation was observed, as compared to TRPV1 KO mice fed the control diet (Fig. 4A,B). Interestingly, fish oil increased oxygen consumption in WT mice, but had no effect in TRPV1 KO mice (Fig. 4C). We also observed that WT mice fed fish oil showed lower fasting plasma glucose and TG concentrations compared to WT mice fed control diet (Supplemental table 3). No differences in fasting glucose and TG concentration were observed in the TRPV1 KO mice.

Figure 4. Fish oil intake reduced the body weight gain and fat accumulation in WT mice, but not TRPV1 KO mice.

Fish oil intake decreased body weight (A) and abdominal WAT (B) gain in WT mice fed a control diet containing high-dose DHA-enriched fish oil (WT-D) and control diet containing high-dose EPA-enriched fish oil (WT-E), as compared to the control diet (WT-C) These effects were not observed in TRPV1 KO mice fed a control diet (KO-C), control diet containing high-dose DHA-enriched fish oil (KO-D), and control diet containing high-dose EPA-enriched fish oil (KO-E) for 10 weeks. Fish oil intake did not increase oxygen consumption (C) in TRPV1 KO mice. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 7–8 animals per group. Different letters indicate significant differences between groups.

Effect of fish oil on UCP1 expression in TRPV1 KO mice

We next evaluated the effects of fish oil on the expression of UCP1 mRNA and protein in TRPV1 KO mice. The UCP1 mRNA and protein expression in the interscapular BAT was significantly induced in the fish oil fed WT mice, as compared to that the WT mice fed control diet. In contrast, TRPV1 KO mice fed either the fish oil or control diets were remarkably similar to WT mice fed a control diet (Fig. 5A,B). Moreover, the inguinal WAT of TRPV1 KO mice showed no changes in UCP1 mRNA and protein expression after fish oil treatment (Fig. 5C,D).

Figure 5. Fish oil intake did not induce UCP1 expression in TRPV1 KO mice.

Fish oil intake did not enhance the UCP1 protein and mRNA expression levels in TRPV1 KO mice, as compared with WT mice, in the interscapular BAT (A,C) and inguinal WAT (B,D). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 7–8 animals per group. Different letters indicate significant differences between groups.

Effect of fish oil on the SNS in TRPV1 KO mice

Finally, we evaluated the effect of fish oil intake on the SNS. As compared to WT mice, fish oil did not alter NA release in the urine of TRPV1 KO mice (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, upregulation of β3AR mRNA in interscapular BAT and inguinal WAT was not significantly altered in TRPV1 KO mice fed fish oil (Fig. 6B,C). Interestingly, fish oil intake significantly increased UCP1 induced by β adrenergic receptor in both interscapular BAT and inguinal WAT of WT mice; however, it had no effect on UCP1 and β3AR expression in TRPV1 KO mice.

Figure 6. Fish oil intake did not induce SNS activation in TRPV1 KO mice.

Fish oil intake increased the amount of urinary NA (A) in WT mice, but not in TRPV1 KO mice. Fish oil intake induced β3AR mRNA expression in the interscapular BAT (B) and inguinal WAT (C) of WT mice, but not TRPV1 KO mice. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 7–8 animals per group. Different letters indicate significant differences between groups. A schematic model of the effect of fish oil intake (D).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effects of fish oil intake on energy expenditure induced by UCP1. Consistent with previous studies, fish oil intake prevented the development of obesity; however, the mechanisms underlying the possible induction of thermogenesis and decreased fat accumulation remained unclear32,33. As shown previously in mice, the anti-obesity effect of fish oil could be dependent on lipid metabolism in the liver34, and fatty acid oxidation in the intestines35. Furthermore, as shown in this study, fish oil intake enhances oxygen consumption and rectal temperature. Thus, fish oil intake decreases in body weight gain and fat accumulation by increasing energy expenditure, suggesting that fish oil intake enhances thermogenesis.

UCP1-mediated thermogenesis in BAT plays an important role in the regulation of energy expenditure. Furthermore, UCP1 is a major determinant of BAT thermogenic activity36. Our data indicate that UCP1 expression in interscapular BAT (classical brown adipocytes) and inguinal WAT (beige/brite adipocytes) was increased by fish oil intake. Interscapular BAT and inguinal WAT share a number of BAT specific genes, such as UCP1, Pgc1α, Cpt1b, Cidea, Prdm16, and Fgf21; however, the two types of adipose tissue express these mRNAs at different levels. Interestingly, the inguinal WAT of fish oil-fed mice expressed beige adipocyte specific genes, such as Tbx137. Furthermore, human BAT isolated from multiple locations, including the supraclavicular and retroperitoneal regions, abundantly express beige adipocyte-specific genes, indicating that human BAT is similar to beige adipocytes38. Recently, it was revealed that inducible beige adipocytes have potent thermogenic activity that is comparable to classical brown adipocytes39. Furthermore, immunochemical analysis of UCP1 reveals the presence of UCP1-positive multilocular adipocytes, a sign of beige adipocytes, in inguinal WAT after fish oil intake. Taken together, fish oil intake induced thermogenesis in both interscapular BAT and inguinal WAT.

Interscapular BAT is heavily innervated by the SNS, and NA released from the activated sympathetic nerves promotes thermogenesis by activating the β3AR40. Moreover, β3AR regulates the thermogenic functions of both brown and white adipocytes40. Fish oil intake increased catecholamine levels in the urine. In addition, fish oil intake increased NA turnover and rate constant in interscapular BAT and inguinal WAT. In particular, enhanced NA turnover and rate constant are considered a direct indicator of sympathetic activity in organs under sympathetic control41. The NA released from the SNS stimulates β3AR in interscapular BAT and inguinal WAT. Stimulation of β3AR leads to the induction of UCP1. Interestingly, β adrenergic blocker-treated and vagotomized mice showed the enhancement of UCP1 expression induced by EPA-enriched fish oil was canceled, suggesting that afferent vagal nerve in gastrointestinal tract mediates the stimulatory actions of fish oil. Taken together, our data indicate that fish oil intake can induce UCP1 in adipose tissues via the SNS.

TRPV4, a member of the TRPV family, is abundant in adipocytes and adipose tissues42,43. Ye et al. reported that mice that were intraperitoneally administered TRPV1 and TRPV4 antagonists showed increased browning (thermogenesis) of adipose tissues and were protected from diet-induced obesity43. However, our study suggested that dietary fish oil intake stimulated thermogenesis through the activation of TRPV1. This difference might have been a result of the different functions of TRPVs in different organs. Our additional experiments showed that both subdiaphragmatic vagotomy surgeries and treatment with a β-adrenergic blocker prevented the increase in UCP1 expression that was induced by the oral administration of fish oil. Moreover, TRPV1 expression in the gastrointestinal tract has been shown to play an important role in the activation of the sympathetic nervous system that is induced by capsinoids, which are TRPV1 agonists. Therefore, we speculated that the expression of TRPV1 in the gastrointestinal tract also plays an important role in the activation of the sympathetic nervous system that results from the enhancement of UCP1 expression that was induced by fish oil intake. However, Ye et al. reported that intraperitoneal injections of TRPV1 and TRPV4 antagonists directly inhibited Ca2 + influx in adipocytes, which resulted in the induction of adipocyte browning43. These results indicated that organs in which TRPV1 is activated are important for the browning of adipocytes.

Dietary factors regulate the development and function of brown and beige adipocytes. Capsaicin in chili peppers, has been shown to enhance catecholamine secretion from the adrenal medulla through activation of the SNS44. Recently, capsinoids, a group of capsaicin analogues, were shown to activate gastrointestinal TRPV1 and induce BAT thermogenesis in humans45 and rodents27. Capsinoids-induced thermogenic sympathetic responses in BAT seem to require the activation of extrinsic nerves connected to the gastrointestinal tract27,31. Moreover, TRPV1 expressing afferent nerves were observed within gastrointestinal tracts46. However, TRPV1 has been reported to express in adipocytes47 and suggested to play roles in the regulation of energy metabolism47,48. Thus, we could not rule out the possibility of the contribution of TRPV1 to the fish oil-induced UCP1 expression in adipose tissues. Further studies are needed to clarify critical TRPV1-expressing tissues in which contribute to this phenomenon. Taken together, fish oil containing EPA and DHA, might activate SNS via the activation of TRPV1 expressing on the afferent nerves in the gastrointestinal tract, leading to the upregulation of UCP1 expression in interscapular BAT and inguinal WAT.

Body weight gain and fat accumulation were not decreased after fish oil intake in TRPV1 KO mice. Furthermore, fish oil intake did not increase oxygen consumption in TRPV1 KO mice. Additionally, UCP1 expression was significantly increased in WT mice following fish oil treatment, but not in TRPV1 KO mice. These findings indicate that TRPV1 plays an important role for upregulation of energy expenditure in response to fish oil intake. Interestingly, EPA and DHA can modulate TRPV1 activity directly and indirectly29. DHA and EPA displace TRPV1 ligand binding and evoke TRPV1 currents28. On the other hand, activation of TRPV1 by EPA and DHA requires activation of protein kinase C (PKC)28. PKC-dependent phosphorylation is known to increase the sensitivity of TRPV149,50. In addition, thermal and chemical stimuli have been reported to activate TRPV1 synergistically51,52,53, and this synergistic activation was also suggested in the case of EPA and DHA29. Thus, it can be postulated that fish oil containing EPA and DHA may have a potential for activating TRPV1 through both direct and indirect manners. Taken together, fatty acids such as EPA and DHA or food ingredients, which activate TRPV1, may elicit sympathetic nerve activation, leading to UCP1-dependent thermogenesis in both interscapular BAT and inguinal WAT.

Alternatively, UCP1 upregulation by fish oil may arise via its anti-inflammatory activity. Indeed, EPA and DHA suppress obesity-induced adipose inflammatory responses by reduction of inflammatory cytokines production in co-cultured adipocytes/macrophage54,55, which is associated with anti-inflammatory macrophage M2 phenotype switching55. More importantly, we previously demonstrated that macrophage-mediated inflammatory cytokine such as tumor necrosis factor α suppresses the induction of UCP1 expression in white adipocytes via extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation in obese and diabetic conditions56. Hence, fish oil-induced upregulation of UCP1 in our observation may be at least in part attributed to its anti-inflammatory action in inguinal WAT.

In summary, fish oil activates and recruits interscapular BAT and inguinal WAT via activation of TRPV1, thereby increasing energy expenditure and decreasing body weight gain and fat accumulation. Based on these results, we propose that the SNS and BAT mediate the thermogenic effect of fish oil. Furthermore, fish oil-mediated thermogenesis via the SNS enhanced energy expenditure and reduced fat accumulation. A schematic model of this unique mechanism is shown in Fig. 6D. Thus, fish oil intake can induce UCP1 expression in classical brown and beige adipocytes via the SNS and TRPV1, and may contribute to an effective treatment for obesity.

Materials and Methods

Materials

DHA-enriched fish oil (DHA 25%, EPA 8%) was a gift from NOF Corporation (Tokyo, Japan) and EPA-enriched fish oil (EPA 28%, DHA 12%) was a gift from Nippon Suisan Kaisya, Ltd., (Tokyo, Japan). Noradrenaline (NA) and a-methyl-DL-tyrosine methyl ester hydrochloride (AMPT) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Potassium dihydrogenphosphate, 3, 4-dihydroxybenzylamine hydrobromide (DHBA), and sodium 1-octanesulphonate were purchased from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan).

Experimental design and diets

C57BL/6 male mice were purchased form LSG Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). TRPV1-deficient (designated KO) C57BL/6 mice were generated by Caterina et al.57. All mice were housed separately at 23 ± 1 °C, maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle, and fed a standard laboratory diet, MF (Oriental Yeast, Tokyo, Japan) for 1 week to stabilize the metabolic conditions before starting the experiments. The mice were divided into five groups (n = 7) according to the type of diet. The composition of diet, expressed as the percent of total calories, was 45% fat, 14% protein, and 41% carbohydrate with a caloric value of 4.74 kcal/g (Supplemental table 4). The concentration of fish oil on a diet with low-dose or high-dose was 1.2% and 2.4%, respectively. The energy intake of all the mice was equalized by pair feeding. All experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of Kyoto University. And the animal care procedures and methods were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Kyoto University (Approved number: 26–49).

Analysis of plasma TG, glucose, and insulin levels

The mice were fasted 5 h before blood collection. The plasma concentrations of glucose, TG, and insulin were determined by the Glucose C-test WAKO (Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan), Triacylglycerol E-test Wako (Wako Pure Chemicals), and Morigana Ultrasensitive Mouse Insulin Assay Kit (Morinaga Institute of Biological Science, Yokohama, Japan), respectively. All kits were used according to manufacturer’s instructions, with the same blood samples.

Measurement of oxygen consumption, RQ and locomotor activity

The oxygen consumption and RQ were measured using an indirect calorimetric system (Oxymax Equal Flow 8 Chamber/Small Subject System; Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA) equipped with an eight-chamber airtight metabolic cage58. Mice were acclimated to the individual metabolic cages for 2 hours prior to the experiment. The data for each metabolic cage were collected every 9 min, with room air as a reference, and measured for 20 h. The RQ was calculated by dividing the CO2 production by the O2 consumption, and was used to estimate the contribution of fats and carbohydrates to in vivo whole-body energy metabolism in mice59. The locomotor activity was measured using an Actimo-S (Bio Research Centre, Nagoya, Japan).

RNA preparation and quantification of gene expression

Total RNA was prepared from animal tissues by using Sepasol-RNA I Super reagent (Nacalai Tesque) in accordance with manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA was revers-transcribed using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega Corporation, Fitchburg, WI, USA) in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions using a thermal cycler (Takara PR Thermal Cycler SP, Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan). To quantify mRNA expression, real-time PCR was performed with a Light cycler system (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) by using SYBR Green fluorescence signals53. Expression data were normalized to mouse 36B4.

Mitochondrial preparations

Interscapular BAT and inguinal WAT mitochondria were prepared as described by Cannon and Lindberg60. The tissues were minced with scissors and homogenized in 300 mM sucrose solution with protease inhibitors. The homogenates were centrifuges at 8,500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. After removing the fat layer and supernatant, the pellets were resuspended, and the nuclei and cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 min. The resulting supernatants were centrifuged at 8,500 × g for 10 min. The final pellets containing the crude mitochondrial fraction were resuspended in a small volume of 300 mM sucrose solution.

Western blotting

The protein concentration was determined by using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Proteins were diluted with Laemmli SDS-PAGE sample buffer and bolied for 5 min in the presence of 2-mercaptoethanol. The samples underwent sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using a 12.5% gel, followed by transfer to an Amersham Hybond-LFP polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). The membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk and 0.1% tween-20 in PBS for 1 h, as previously described61. After blocking, the membranes were incubated in a rabbit anti-UCP1 antibody (Sigma) overnight at 4 °C. Next, the membranes were incubated in HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, San Antonio, TX, USA) for 2 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized by ELC chemiluminescence detection (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Immunoreactive protein bands were quantified by using the Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Histological analysis

The interscapular BAT, and inguinal WAT, were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. For UCP1 immunohistochemistry, paraffin-embedded sections (6μm) were incubated with anti-UCP1 (Sigma), followed by detection using the ABC62 method. Nuclei were counterstained with modified Mayer’s hematoxylin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany)62.

Extraction of tissue catecholamines

The heart, interscapular BAT, and inguinal WAT were rapidly removed, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. DHBA was added as an internal standard, and the organs were homogenized in 1 mL of 0.4 M perchloric acid (PCA). After centrifugation, the catecholamines in the supernatant were purified with activated alumina, as described previously41.

Extraction of urine catecholamines

Mice were acclimated to the individual metabolic cages for 2 hours prior to the experiment, and urine samples were collected for 48 h. The urine was collected in 1 mL of 6 M HCl solution for collection and storage. Urine samples were purified via activated alumina, as previously described63.

Catecholamine assays

Catecholamines were eluted with 100 μL of 0.4 M PCA. Catecholamines were assayed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection63. The detector potential was set at 700 mV maintained across a glassy carbon working electrode. Methanol-buffer (10:90, v/v) composed of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 3.5), 10 μM EDTA·2Na, and 100 mg/L sodium 1-octanesulphonate was used as the mobile phase at flow rate of 1 mL/min.

Measurement of NA turnover rate

The experiment was started at 8 AM and measured by determining the concentration of NA in the heart, interscapular BAT, and inguinal WAT at 0, 8, and 16 h following intraperitoneal injection of AMPT (250 mg/kg). The organs were rapidly dissected, weighed, and frozen in nitrogen to measure NA content. The NA turnover rate was calculated as the slope of the decline in log-trans-formed NA concentration after intraperitoneal injection of AMPT64.

Treatment with propranolol

Mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of propranolol (2mg/kg)65. Thirty minutes after the injection, mice were given an oral administration of fish oil. After four hours, mice were decapitated and the organs were rapidly dissected, weighed, and frozen in nitrogen.

Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (15 mg/kg ip). After laparotomy, the two trunks of the vagus nerve were identified under an operating microscope, silk sutures were tied a few millimeters apart around each vagal trunk before bifurcation of the gastric branch and the hepatic and celiac branches, and the nerve was cut between the sutures66. For the sham operations, the vagus was similarly exposed but neither ligated nor cut. All operated mice lost weight for the 2–3 days after surgery, and the mortality rate reached 15%. On the basis of changes in body weight, ingestion patters became normal 3 days after vagotomy.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 12.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc. Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical differences between the experimental groups were assessed by ANOVA, followed by the Turkey-Kramer HSD post hoc test. Different letters indicate significant differences between groups (p < 0.05).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Kim, M. et al. Fish oil intake induces UCP1 upregulation in brown and white adipose tissue via the sympathetic nervous system. Sci. Rep. 5, 18013; doi: 10.1038/srep18013 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly thank Dr. Junichiro Hata, Dr. Sou Matsuda, and Dr. Takeshi Okubo for their kind support in performing experiments, and Prof. Yasutake Shimizu, Prof. Takahiko Shiina, and Mr. Hiroyuki Nakamori for their kind support in vagotomy surgery. This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (22228001 and 24688015). Rina Yu was supported by the Science Research Center Program (Center for Food & Nutritional Genomics Research, Grant 2015R1A5A6001906) of the NRF of Korea founded by the Korean Government (MEST).

Footnotes

Author Contributions M.J.K. performed experiments and wrote the manuscript. T.G. analysed data and edited the manuscript. R.Y., K.U., M.T., Y.K. and N.T. performed experiments and edited the manuscript. T.K. conceived the study, performed experiments and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Park Y. & Harris W. S. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation accelerates chylomicron triglyceride clearance. J Lipid Res. 44, 455–463 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama M., Origasa H. & Shirato K. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients (JELIS): a randomised open-label, blinded endpoint analysis. Lancet. 369, 1090–1098 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casula M., Soranna D. & Corrao G. Long-term effect of high dose omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for secondary prevention of cardiovascular outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized, placebo controlled trials. Atheroscler Suppl. 14, 243–251 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skilton M. R., Mikkilä V. & Raitakari O. T. Fetal growth, omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids, and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis: preventing fetal origins of disease ? The cardiovascular risk in young finns study. Am J Clin Nutr. 97, 58–65 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puglisi M. J., Hasty A. H. & Saraswathi V. The role of adipose tissue in mediating the beneficial effects of dietary fish oil. J Nutr Biochem. 22, 101–108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J., Takahashi M. & Ezaki O. Fish oil feeding decreases mature sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP-1) by down-regulation of SREBP-1c mRNA in mouse liver. A possible mechanism for down-regulation of lipogenic enzyme mRNAs. J Biol Chem. 274, 25892–25898 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawada T., Kayahashi S. & Fushiki T. Fish (Bonito) oil supplementation enhances the expression of uncoupling protein in brown adipose tissue of rat. J. Agric. Food Chem. 46, 1225–1227 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Kimura R., Takahashi N. & Kawada T. DHA attenuates postprandial hyperlipidemia via activating PPARα in intestinal epithelial cells. J Lipid Res. 54, 3258–3268 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neschen S., Moore I. & Shulman G. I. Contrasting effects of fish oil and safflower oil on hepatic peroxisomal and tissue lipid content. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 282, 395–401 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousset S., Alves-Guerra M. C. & Ricquier D. The biology of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Diabetes. 53, 130–135 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann H. M., Golozoubova V. & Nedergaard J. UCP1 ablation induces obesity and abolishes diet-induced thermogenesis in mice exempt from thermal stress by living at thermoneutrality. Cell Metab. 9, 203–209 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypess A. M., Lehman S. & Kahn C. R. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med. 360, 1509–1517 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell B. B. & Bachman E. S. Beta-Adrenergic receptors, diet-induced thermogenesis, and obesity. J Biol Chem. 278, 29385–29388 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell B. B. & Spiegelman B. M. Towards a molecular understanding of adaptive thermogenesis. Nature. 404, 652–660 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajimura S. & Saito M. A new era in brown adipose tissue biology: molecular control of brown fat development and energy homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol. 76, 225–249 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabalina I. G., Petrovic N. & Nedergaard J. UCP1 in brite/beige adipose tissue mitochondria is functionally thermogenic. Cell Rep. 5, 1196–1203 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M., Okamatsu-Ogura Y. & Tsujisaki M. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes. 58, 1526–1531 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypess A. M., Lehman S. & Kahn C. R. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med. 360, 1509–1517 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen K. A., Lidell M. E. & Nuutila P. Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N Engl J Med. 360, 1518–1525 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Marken Lichtenbelt W. D., Vanhommerig J. W. & Teule G. J. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N Engl J Med. 361, 1500–1508 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousin B., Cinti S. & Casteilla L. Occurrence of brown adipocytes in rat white adipose tissue: molecular and morphological characterization. J Cell Sci. 103, 931–942 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase I., Yoshida T. & Saito M. Expression of uncoupling protein in skeletal muscle and white fat of obese mice treated with thermogenic beta 3-adrenergic agonist. J Clin Invest. 97, 2898–2904 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerling J. J., Boon M. R. & Rensen P. C. Sympathetic nervous system control of triglyceride metabolism: novel concepts derived from recent studies. J Lipid Res. 55, 180–189 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Carter C. R. & Light P. E. Intracellular long-chain acyl CoAs activate TRPV1 channels. PLoS One. 9, e96597 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludy M. J. & Mattes R. D. The effects of hedonically acceptable red pepper doses on thermogenesis and appetite. Physiol Behav. 102, 251–258 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Lazaro S. L., Serrano-Flores B. & Rosenbaum T. Structural determinants of the transient receptor potential 1 (TRPV1) channel activation by phospholipid analogs. J Biol Chem. 289, 24079–24090 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata F., Inoue N. & Fushiki T. Non-pungent capsaicin analogs (capsinoids) increase metabolic rate and enhance thermogenesis via gastrointestinal TRPV1 in mice. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 73, 2690–2697 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matta J. A., Miyares R. L. & Ahern G. P. TRPV1 is a novel target for omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Physiol. 15, 397–411 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonelli M., Graciano M. F. & Britto L. R. TRP channels, omega-3 fatty acids, and oxidative stress in neurodegeneration: from the cell membrane to intracellular cross-links. Braz J Med Biol Res. 44, 1088–1096 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata F., Inoue N. & Fushiki T. Effects of CH-19 sweet, a non-pungent cultivar of red pepper, in decreasing the body weight and suppressing body fat accumulation by sympathetic nerve activation in humans. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 70, 2824–2835 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K., Tsukamoto-Yasui M. & Kato F. Intragastric administration of capsiate, a transient receptor potential channel agonist, triggers thermogenic sympathetic responses. J Appl Physiol. 110, 789–798 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadurskis A., Dicker A. & Nedergaard J. Polyunsaturated fatty acids recruit brown adipose tissue: increased UCP content and NST capacity. Am J Physiol. 269, 351–360 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flachs P., Horakova O. & Kopecky J. Polyunsaturated fatty acids of marine origin upregulate mitochondrial biogenesis and induce beta-oxidation in white fat. Diabetologia. 48, 2365–2375 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi Y., Yahagi N. & Shimano H. Polyunsaturated fatty acids selectively suppress sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 through proteolytic processing and autoloop regulatory circuit. J Biol Chem. 285, 11681–11691 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schothorst E. M., Flachs P. & Keijer J. Induction of lipid oxidation by polyunsaturated fatty acids of marine origin in small intestine of mice fed a high-fat diet. BMC Genomics. 10, 110 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beranger G. E., Karbiener M. & Amri E. Z. In vitro brown and “brite”/“beige” adipogenesis: human cellular models and molecular aspects. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1831, 905–914 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan T., Liang X. & Kuang S. Distinct populations of adipogenic and myogenic Myf5-lineage progenitors in white adipose tissues. J Lipid Res. 54, 2214–2224 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp L. Z., Shinoda K. & Kajimura S. Human BAT possesses molecular signatures that resemble beige/brite cells. PLoS One. 7, e49452 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamatsu-Ogura Y., Fukano K. & Saito M. Thermogenic ability of uncoupling protein 1 in beige adipocytes in mice. PLoS One. 8, e84229 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S. β-Adrenoceptor Signaling Networks in Adipocytes for Recruiting Stored Fat and Energy Expenditure. Front Endocrinol. 2, 1–7 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Young J. B., Saville E. & Landsberg L. Effect of diet and cold exposure on norepinephrine turnover in brown adipose tissue of the rat. J Clin Invest. 69, 1061–1071 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani D. F., Ghandour R. A. & Amri E. Z. The ω6-fatty acid, arachidonic acid, regulates the conversion of white to brite adipocyte through a prostaglandin/calcium mediated pathway. Mol Metab. 3, 834–847 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L. Kleiner S. & Spiegelman B. M. TRPV4 is a regulator of adipose oxidative metabolism, inflammation, and energy homeostasis. Cell. 151, 96–110 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T., Kawada T. & Iwai K. Adrenal sympathetic efferent nerve and catecholamine secretion excitation caused by capsaicin in rats. Am J Physiol. 255, 23–27 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M. & Yoneshiro T. Capsinoids and related food ingredients activating brown fat thermogenesis and reducing body fat in humans. Curr Opin Lipidol. 24, 71–77 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward S. M., Bayguinov J. & Berthoud H. R. Distribution of the vanilloid receptor (VR1) in the gastrointestinal tract. J Comp Neurol. 465, 121–135 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. L., Yan Liu. D. & Tepel M. Activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1 channel prevents adipogenesis and obesity. Circ Res. 100, 1063–1070 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baboota R. K., Singh D. P. 1. & Bishnoi M., Capsaicin induces “brite” phenotype in differentiating 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. PLoS One. 9, e103093 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M., Wada M. & Masu M. Potentiation of capsaicin receptor activity by metabotropic ATP receptors as a possible mechanism for ATP-evoked pain and hyperalgesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 98, 6951–6956 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numazaki M., Tominaga T. & Tominaga M. Direct phosphorylation of capsaicin receptor VR1 by protein kinase Cε and identification of two target serine residues. J Biol Chem. 277, 13375–13378 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina M. J., Schumacher M. A. & Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature, 389, 816–824 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M., Caterina M. J. & Julius D. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neurone, 21, 531–543 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordt S. E., Tominaga M. & Julius D. Acid potentiation of the capsaicin receptor determined by a key extracellular site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 97, 8134–8139 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGillicuddy F. C., Harford K. A. & Roche H. M. Lack of interleukin-1 receptor I (IL-1RI) protects mice from high-fat diet-induced adipose tissue inflammation coincident with improved glucose homeostasis. Diabetes. 60, 1688–1698 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver E., McGillicuddy F. C. & Roche H. M. Docosahexaenoic acid attenuates macrophage-induced inflammation and improves insulin sensitivity in adipocytes-specific differential effects between LC n-3 PUFA. J Nutr Biochem. 23, 1192–1200 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto T., Takahashi N. & Kawada T. Inflammation induced by RAW macrophages suppresses UCP1 mRNA induction via ERK activation in 10T1/2 adipocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 304, 729–738 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina M. J., Leffler A. & Julius D. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 288, 306–313 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto T., Lee J. Y. & Kawada T. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha stimulates both differentiation and fatty acid oxidation in adipocytes. J Lipid Res. 52, 873–884 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesey G. & Elia M. Estimation of energy expenditure, net carbohydrate utilization, and net fat oxidation and synthesis by indirect calorimetry: evaluation of errors with special reference to the detailed composition of fuels. Am J Clin Nutr. 47, 608–628 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon B. & Lindberg O. Mitochondria from brown adipose tissue: isolation and properties. Methods Enzymol. 55, 65–78 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto T., Takahashi N. & Kawada T. Phytol directly activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) and regulates gene expression involved in lipid metabolism in PPARalpha-expressing HepG2 hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 337, 440–445 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M., Nakagami H. & Kaneda Y. Essential role for miR-196a in brown adipogenesis of white fat progenitor cells. PLoS Biol. 10, e1001314 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oi-Kano Y., Kawada T. & Iwai K. Oleuropein supplementation increases urinary noradrenaline and testicular testosterone levels and decreases plasma corticosterone level in rats fed high-protein diet. J Nutr Biochem. 24, 887–893 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie B. B., Costa E. & Smookler H. H. Application of steady state kinetics to the estimation of synthesis rate and turnover time of tissue catecholamines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 154, 493–498 (1966). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T. & Yokotani K. Acute cold exposure-induced down-regulation of CIDEA, cell death-inducing DNA fragmentation factor-alpha-like effector A, in rat interscapular brown adipose tissue by sympathetically activated beta3-adrenoreceptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 387, 294–299 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvell A. & Lindström P. Vagotomy in young obese hyperglycemic mice: effects on syndrome development and islet proliferation. Am J Physiol. 274, E1034–1039 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.