Abstract

Background

Lgr5 has recently been identified as a reliable biomarker of cancer stem cells (CSCs) in colorectal cancer (CRC); however, its prognostic value is still controversial.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and Wanfang databases with identical strategies to retrieve articles. We evaluated the impact of Lgr5 expression on survival of CRC patients through meta-analysis.

Results

A total of 12 studies comprising 2600 patients revealed that Lgr5 overexpression was negatively associated with overall survival (OS) (HR = 1.73, 95 % CI: 1.28–2.33; P = 0.00) and disease free survival (DFS) (HR = 2.89, 95 % CI: 1.89–4.44; P = 0.000) in CRC patients. Subgroup analysis suggested that Lgr5 overexpression was significantly associated with worse OS in subgroups with IHC as the method of Lgr5 assessment (HR = 2.01, 95 % CI: 1.39–2.89; P = 0.001), patients from Asia (HR = 1.81, 95 % CI: 1.27–2.58; P = 0.000), and NOS scores greater than 6 (HR = 2.12, 95 % CI: 1.41–3.19; P = 0.000). Furthermore, sensitivity analysis showed that the estimated HR ranged from 1.6 to 1.86 upon excluding one study sequentially from each analysis. In addition, Lgr5 overexpression was significantly associated with deep invasion of CRC (OR = 0.39, 95 % CI: 0.17–0.87; P = 0.002), lymphnode metastasis (OR = 0.45, 95 % CI: 0.26–0.76; P = 0.003), distant metastasis (OR = 0.37, 95 % CI: 0.22–0.62; P = 0.000), and AJCC stage (OR = 0.35, 95 % CI: 0.15–0.78; P = 0.01). However, Lgr5 overexpression was not correlated with tumor grade (OR = 0.75 95 % CI: 0.37–1.54; P = 0.433).

Conclusions

This study shows that Lgr5 can be a valuable and reliable prognostic factor of colorectal cancer progression.

Keywords: Lgr5, Prognostic value, Clinical-pathological differences, Colorectal cancer, Meta-analysis

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common form of cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States [1]. Despite the enormous progress that has been made in CRC treatment, the overall mortality of CRC is still around 40 % [2]. Currently, TNM classification, including local tumor infiltration depth, lymph node involvement, and distant organ metastasis, is the main criterion for identifying those patients who carry a high risk for disease relapse and poor outcomes [3]. Unfortunately, 40–60 % of cases classified as either stage II or stage III will relapse or develop metastases following curative resection [4]. In addition, patients can follow significantly different clinical courses despite being diagnosed in the same stage. Therefore, identification of novel prognostic factors to distinguish high-risk groups is imperative for the improvement of therapeutic approaches in CRC treatment.

Recent mounting evidence indicates that cancer stem cells (CSCs) play a crucial role in tumor initiation, therapy resistance, disease relapse, and tumor progression [5–7]. A number of studies have demonstrated that expression of CSC markers in CRC have prognostic significance [8, 9]. CD133 was initially identified as a biomarker in primary CRC [10, 11] where it was believed to be widely expressed in human primary colon cancer epithelial cells. However, the CD133- subpopulation is now known to be composed mostly of stromal and inflammatory cells [12] that possess the ability to initiate xenograft tumors. Alternatively, Leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 5 (Lgr5), a member of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family of proteins, has recently been reported as a reliable biomarker of CSCs in CRC [13]. Many studies have demonstrated that Lgr5 protein is overexpressed in CRC and is associated with tumor initiation, 5-FU-based chemotherapy resistance, and recurrence [14–18]. Therefore, Lgr5 expression is thought to be a potential biomarker related to poor prognosis in CRC. However, a recent, retrospective study comprising 891 colorectal adenocarcinomas revealed that Lgr5 did not have prognostic significance in CRC [19]. These contradictory results highlight the need to systematically analyze the data of Lgr5 expression in CRC to draw a reasonable conclusion about its prognostic significance.

In this study, we performed a meta-analysis to explore the association between Lgr5 expression and the prognosis of CRC. The correlation of Lgr5 expression with clinical-pathological features in CRC, such as tumor grade and tumor stage, was also investigated.

Methods

Literature search

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and Wanfang databases using the following terms: “Lgr5”, “colorectal neoplasms”, “colorectal cancer”, “colon cancer”, “rectal cancer”, and “prognosis”. We also searched references cited in retrieved articles to identify additional eligible studies. The last search update was February 15th, 2014. In studies with overlapping patients, the most informative one was chosen to avoid duplicate information.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The eligible studies included in our meta-analysis met the following inclusion criteria: (1) evaluated the relationship between Lgr5 expression in human CRC samples and overall survival (OS), disease free survival (DFS), or clinicopathological characteristics of CRC; (2) provided sufficient data to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) or odds ratios (ORs) and their 95 % confidence intervals (CIs); (3) published in English or Chinese. The following articles were excluded: (1) articles without original data such as letters, case reports, reviews, or conference abstracts; (2) articles published in a language other than English or Chinese; (3) articles that lacked the necessary data for estimating HRs or ORs and the corresponding 95 % CIs.

Data extraction and assessment of study quality

Two authors independently reviewed and extracted data from each eligible study. Disagreements in data extraction were arbitrated by a third investigator. The following data were retrieved from the studies: name of the first author, year of publication, country of origin of the patients, number of patients included in the study, method used to detect Lgr5, cut-off value of Lgr5 expression, study design, clinicopathological features, and survival data. The quality of each eligible study was assessed according to the Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale.

Statistical analysis

To pool the survival data quantitatively, the impact of Lgr5 overexpression on OS or DFS of patients with CRC was evaluated by HRs with 95 % CIs. The HRs with 95 % CIs were estimated according to the methods reported by Parmar [20]. We used the raw data directly if HRs and their corresponding 95 % CIs were described in the publication. Otherwise, the value of HRs with 95 % CIs was estimated by other parameters, such as the O-E statistic and variance. Also, Kaplan-Meier curves of OS or DFS were read by Engauge Digitizer 4.1 (http://digitizer.sourceforge.net/). ORs (odds ratios) with 95 % CIs were used to determine the relationship between Lgr5 overexpression and clinicopathological parameters of CRC, such as tumor grade, AJCC stage, depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis, and distant metastasis. An observed HR > 1 and an observed OR < 1 indicated a worse prognosis for survival and unfavorable parameters in patients that overexpressed Lgr5. The impact of Lgr5 overexpression on survival or clinicopathological features was considered to be statistically significant if the 95 % CI did not overlap with 1.

The heterogeneity that exists in a meta-analysis due to the variation in outcomes between studies was evaluated by Chi-square, according to Peto’s method [21]. The inconsistency index (I2) statistic (range from 0 % to 100 %) was used to quantify the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error [22]. A P < 0.10 for the Q-test indicated heterogeneity exists among the studies, then we used the random-effects model (the DerSimonian and Laird method) [22]. Otherwise, we adopted the fixed-effects model (Mantel-Haenszel) to calculate the pooled ORs and HRs [22]. Both the Begg’s test and Egger’s test were used to determine publication bias where p < 0.05 indicated bias. All calculations were performed using STATA 12.0 software (Stata Corporation, Collage Station, Texas, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Search results and description of the studies

Upon analysis of the title and abstract of 348 potential studies that were retrieved using the search strategy described above, we identified 129 articles involving the survival risk of CRC and Lgr5 expression. Of these 129 studies, 42 did not offer sufficient data to calculate the HR or OR, three overlapped with other studies, and 72 did not involve clinical specimens resulting in a total of twelve studies that were included in our meta-analysis [14, 19, 23–32]. In addition, no another study was identified through searching references cited in retrieved articles. A detailed search strategy is described in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the selection procedure for the studies

The characteristics of the nine eligible studies, which were retrospective case–control studies published between 2010 and 2014, are summarized in Table 1. This meta-analysis involved a total of 2600 CRC patients with sample sizes ranging from 44 to 891 patients. Of the twelve studies, seven evaluated patients from China, three assessed patients from Japan,and one each examined patients from America and Spain. Furthermore, four studies assessed the relationship between Lgr5 expression and DFS of CRC patients while ten studies evaluated the correlation between Lgr5 expression and OS of CRC patients. With regards to the method of analysis, nine studies assessed Lgr5 expression using immunohistochemistry (IHC), two determined Lgr5 expression by RT-PCR, and the remaining study evaluated Lgr5 expression through in situ hybridization (ISH).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included for the meta-analysis

| First author | Year | Country | Patient (M/F) | Age (year) | Technology | Lgr5 positive threshold | HR (95 % CI) of OS | HR (95 % CI) of DFS | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu | 2014 | China | 363 (200/166) | 59mean | IHC | NA | 2.604 (1.894–3.584) | NA | 7 |

| He | 2014 | China | 53 (29/24) | NA | IHC | NA | 2.482 (1.52–4.283) | NA | 7 |

| Gao | 2014 | China | 44 (22/20) | 59median | IHC | The percentage of stained cells ≥ 10 % | 2.299 (0.922–5.714) | NA | 6 |

| Wu | 2012 | China | 192 (120/72) | 62median | IHC | Multiplying the intensity and the quantity score > 5 | 2.768 (1.619–4.732) | NA | 8 |

| Hsu | 2013 | China | 296 (169/127) | 63.5mean | IHC | The percentage of stained cells multiplied by the intensity scores ≥180 | NA | 2.21 (1.11–4.37) | 7 |

| Saiqusa | 2012 | Japan | 52 (41/11) | 64.5median | IHC | The percentage of stained cells ≥ 50 % | 1.061 (0.299–3.771) | 4.942 (1.39–17.577) | 6 |

| Ziskin | 2012 | America | 891 (467/424) | 71.4mean | ISH | Intensity score >1 | 1.15 (0.95–1.4) | NA | 7 |

| Valladares-Ayerbes | 2012 | Spain | 54 (33/21) | 62.7mean | QRT-PCR | 11.6 | 2.517 (0.924–6.858) | 2.995 (1.192–7.527) | 8 |

| Takahashi | 2011 | Japan | 180 (105/75) | NA | QRT-PCR | Median value | 0.909 (0.535–1.543) | 3.3 (1.49–7.33) | 6 |

| Bao | 2012 | China | 246 (131/115) | 63mean | IHC | The percentage of stained cells ≥ 5 % | 1.122 (0.866–1.448) | NA | 4 |

| Peng | 2010 | China | 169 (101/68) | 57mean | IHC | The percentage of stained cells ≥ 10 % | 2.16 (1.35–3.45) | NA | 7 |

| Takeda | 2010 | Japan | 60 (32/28) | 65.7mean | IHC | The percentage of stained cells ≥ 5 % | NA | NA | 7 |

Methodological quality of the studies

We assessed the quality of the 12 eligible case–control studies according to the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), a method developed as a collaborative effort between the Universities of Newcastle, Australia and Ottawa, Canada. NOS scores were determined by judging the studies on items in three general categories, including the selection of the study populations, the comparability of the populations, and the ascertainment of either the exposure or the outcome of interest. Scores ranged from 0 (lowest) to 9 (highest), and studies with scores of 7 or more were defined as high quality studies. The quality scores of each study are summarized in Table 1. The median and mean score of these 12 studies were 7 and 6.67, respectively, indicating that they were of high quality.

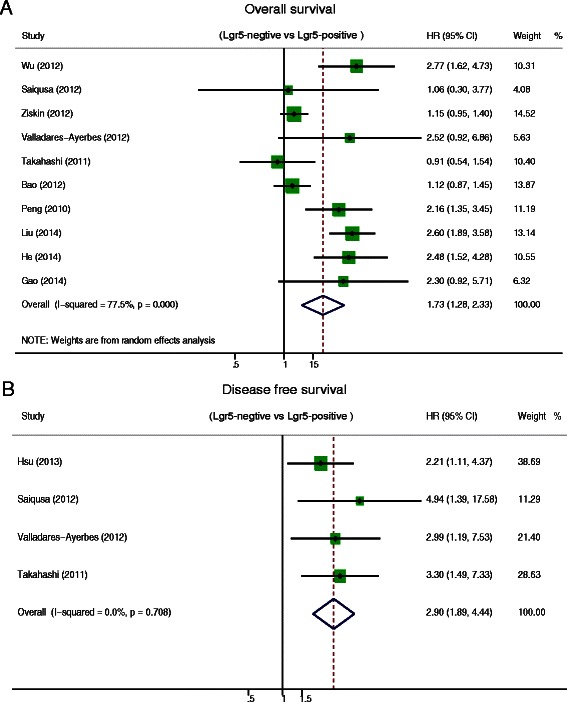

Correlation of Lgr5 overexpression with decreased OS and DFS in CRC

We performed a meta-analysis on ten studies to evaluate the association between Lgr5 overexpression and OS and a meta-analysis on four studies to determine the association between Lgr5 overexpression and DFS. The pooled hazard ratio (HR) for OS was 1.73 (95 % CI: 1.28–2.33; Z = 3.59; P = 0.00) (Fig. 2) with heterogeneity (I2 77.5 % P = 0.00), indicating that the HR of overall death was 1.73-fold higher in patients with increased levels of Lgr5; the pooled HR for DFS was 2.89 (95 % CI: 1.89–4.44; Z = 4.89; P = 0.000) without heterogeneity (I2 0 % P = 0.708) (Fig. 2). These results suggest that Lgr5 overexpression is significantly correlated with a worse prognosis in CRC patients.

Fig. 2.

Hazard ratio (HR) of Lgr5 overexpression associated with (a) overall survival (OS) and (b) disease free survival (DFS)

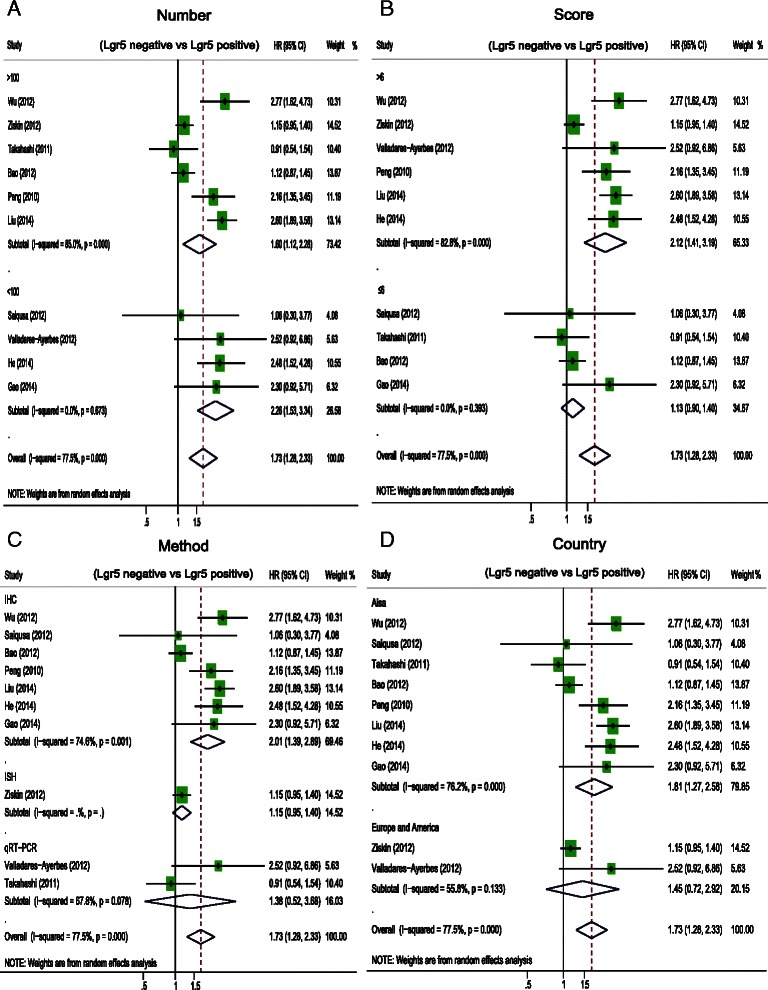

Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis of the relationship between Lgr5 overexpression and OS in CRC

We performed subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis in order to address the heterogeneity that was observed in the correlation between Lgr5 overexpression and decreased OS in CRC patients. The characteristics that we evaluated for the subgroup analysis were the following: number of patients involved in the study, the country of origin of the patients, the method used to determine Lgr5 expression, and NOS scores of the study. Lgr5 overexpression was correlated with worse OS in subgroups with patients from Asia (HR = 1.81, 95 % CI: 1.27–2.58; P = 0.000), IHC as a method of Lgr5 assessment (HR = 2.01, 95 % CI: 1.39–2.89; P = 0.001), and NOS scores greater than 6 (HR = 2.12, 95 % CI: 1.41–3.19; P = 0.000) (Fig. 3) (Table 2). We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to evaluate the effect of a single study on the overall estimate by sequentially excluding each study, as outlined in Table 2. Upon omitting each of the indicated studies, the estimated HR ranged from 1.6 to 1.86 (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Hazard ratio (HR) of Lgr5 overexpression associated with overall survival (OS) in the subgroup of (a) patient sample size, (b) NOS score of study, (c) the Lgr5 assessment method, and (d) patients’ country of origin

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of pooled hazard ratios of colorectal patients with Lgr5 overexpression

| Heterogeneity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stratified analysis | Number of studies | Number of patients | Pooled HR (95 % CI) | P value | I2(%) | P value | Interaction p value |

| Study location | 0.518 | ||||||

| Asia | 8 | 1299 | 1.81 (1.27–2.58) | 0.001 | 76.2 | 0.000 | |

| Europe and America | 2 | 945 | 1.45 (0.72–2.92) | 0.299 | 55.8 | 0.133 | |

| Number of patients | 0.38 | ||||||

| >100 | 6 | 2041 | 1.6 (1.12–2.29) | 0.01 | 85 | 0.043 | |

| <100 | 4 | 203 | 2.26 (1.53–3.34) | 0.000 | 0 | 0.673 | |

| Method of measurement | 0.15 | ||||||

| IHC | 7 | 1119 | 2.01 (1.39–2.89) | 0.000 | 74.6 | 0.001 | |

| ISH | 1 | 891 | 1.15 (0.95–1.4) | 0.158 | |||

| qRT-PCR | 2 | 234 | 1.38 (0.52–3.68) | 0.521 | 67.8 | 0.078 | |

| NOS score | 0.055 | ||||||

| >6 | 6 | 1669 | 2.12 (1.41–3.19) | 0.000 | 82.8 | 0.000 | |

| ≦6 | 4 | 575 | 1.13 (0.9–1.4) | 0.291 | 55.9 | 0.393 | |

Table 3.

Meta sensitivity analysis of Lgr5 expression and OS

| Study omitted | Estimated HR | Low value of 95 % CI | High value of 95 % CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wu (2012) [23] | 1.6325674 | 1.2023937 | 2.2166421 |

| Saiqusa (2012) [24] | 1.7648035 | 1.295853 | 2.4034605 |

| Ziskin (2012) | 1.8513726 | 1.3232487 | 2.5902767 |

| Valladares-Ayerbes (2012) [25] | 1.6885946 | 1.2394606 | 2.300478 |

| Takahashi (2011) [26] | 1.8601217 | 1.3568895 | 2.5499887 |

| Bao (2012) [29] | 1.8537774 | 1.3164659 | 2.6103909 |

| Peng (2010) [28] | 1.6803607 | 1.2180028 | 2.3182311 |

| Liu (2014) [32] | 1.6021169 | 1.2043179 | 2.1313131 |

| He (2014) [31] | 1.6534556 | 1.2091391 | 2.2610431 |

| Gao (2014) [30] | 1.6943128 | 1.2407216 | 2.3137312 |

| Combined | 1.7265576 | 1.2812517 | 2.3266318 |

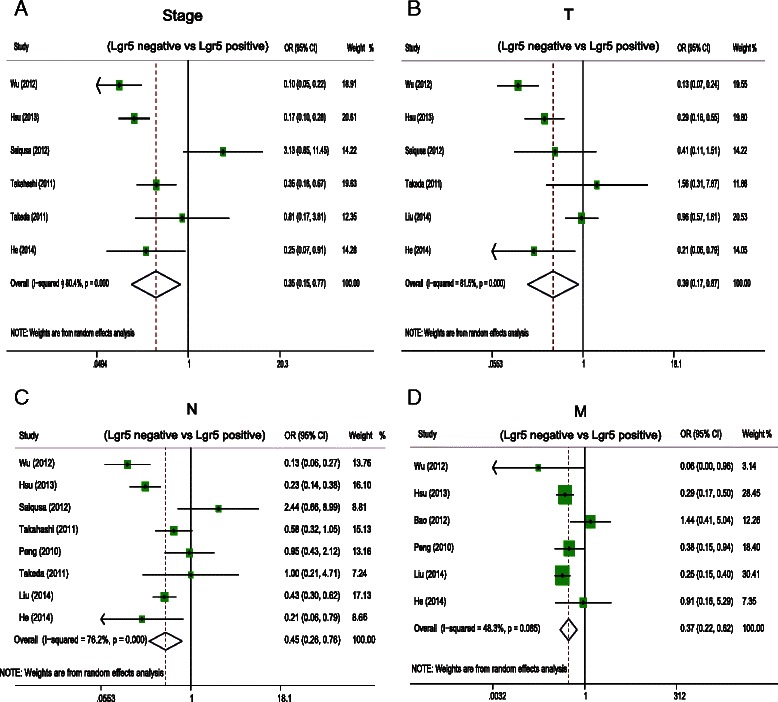

Impact of Lgr5 overexpression on clinicopathological features of CRC

Next, we examined the relationship between Lgr5 overexpression and several clinicopathological parameters of CRC (Fig. 4). Lgr5 overexpression appeared to be significantly associated with deep invasion of CRC (OR = 0.39, 95 % CI: 0.17–0.87; P = 0.002), lymph node metastasis (OR = 0.45, 95 % CI: 0.26–0.76; P = 0.003), distant metastasis (OR = 0.37, 95 % CI: 0.22–0.62; P = 0.000), and AJCC stage (OR = 0.35, 95 % CI: 0.15–0.78; P = 0.01). (Figure 4); however, it was not correlated with tumor grade (OR = 0.75 95 % CI: 0.37–1.54; P = 0.433).

Fig. 4.

Odds ratio (OR) of Lgr5 overexpression associated with clinicopathological features of colorectal cancer. a The pooled OR and its corresponding 95 % CI of Lgr5 overexpression with AJCC stage. b The pooled OR and its corresponding 95 % CI of Lgr5 overexpression with primary tumor. c The pooled OR and its corresponding 95 % CI of Lgr5 overexpression with lymph node metastasis. d The pooled OR and its corresponding 95 % CI of Lgr5 overexpression with distant metastasis

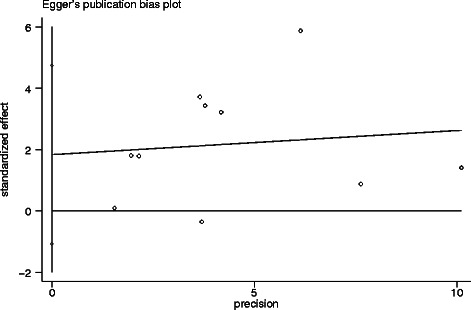

Publication bias

We assessed the potential publication bias both graphically, through funnel plots of the Egger’s test on OS (Fig. 5), and statistically, by the Egger’s and Begg’s test. The symmetry of the funnel plots and the p-values from the statistical analysis suggest no publication bias.

Fig. 5.

Egger’s publication bias plot. It showed no publication bias for studies regarding the association of Lgr5 with overall survival (OS) in the meta-analysis. Each point represents a separate study for the indicated association

Discussion

Lgr5, also known as GPR49, has been reported to be a reliable biomarker of CSCs in CRC [13]. Overexpression of Lgr5, through an in vitro assay, resulted in enhanced proliferation and resistance to chemotherapy [14, 18]. Consistent with these results, Lgr5 ablation in CRC cell lines inhibited cell growth, enhanced apoptosis, and increased the sensitivity of cells to chemotherapy [14]. The close relationship between Lgr5 and Ki-67 further supports the correlation between Lgr5 overexpression and increased proliferative capability [23]. Furthermore, Lgr5 was recently shown to be involved in the carcinogenesis of CRC as a target of the Wnt signaling pathway [33, 34]. Despite these data, the relationship between Lgr5 expression and prognosis of CRC is still not completely understood and Lgr5, as a useful biomarker associated with poor prognosis in CRC, still remains controversial. Therefore, in this study, we performed a meta-analysis to systematically evaluate the association between Lgr5 expression and the prognosis of CRC.

Previous studies reported that Lgr5 was overexpressed in human colon tumors, as compared to normal colon tissues [16]. Lgr5 expression was also significantly correlated with worse prognosis in 192 CRC patients by immunohistochemistry [23]. Consistent with these findings, our meta-analysis demonstrated that elevated Lgr5 expression was negatively associated with OS and DFS in CRC patients, suggesting an important role for Lgr5 in tumor progression. Subgroup analysis further distinguished that Lgr5 overexpression was correlated with worse OS when patients from Asia,IHC as a method of Lgr5 assessment and NOS scores were greater than 6. The outcome of the sensitivity analysis corroborated the relationship between Lgr5 overexpression and worse OS in CRC patients. Furthermore, several studies showed that the expression of Lgr5 was up-regulated in advanced CRC [14, 17, 26]. The relationship between Lgr5 expression and clinicopathological parameters was analyzed, and the results showed that Lgr5 overexpression was significantly correlated with deep invasion, lymph node metastasis,distant metastasis, and advanced AJCC stage. These results suggest that Lgr5 expression could serve as a valuable prognostic factor for CRC patients.

However, inevitably, some limitations exist in our meta-analysis. First, although random effects model was used to deal with heterogeneity, the inter-study heterogeneity caused by the use of different populations, varying detection methods, and different cutoff values was inevitable. Second, the number of studies included in subgroup analysis according to country and measurement method was relatively small, it may result in bias and further studies will need to be performed in order to confirm and strengthen these results. Finally, the results of retrospective case–control studies in our meta-analysis were less reliable than that of prospective cohort studies or randomized controlled trials.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results show that Lgr5 overexpression is significantly associated with poor OS as well as DFS of CRC patients. Furthermore, advanced AJCC stage, deep invasion, and distant metastasis seems to be more frequent in patients that overexpress Lgr5. Therefore, Lgr5 overexpression appears to be a valuable prognostic factor and a reliable indicator of CRC progression.

Acknowledgments

Data analysis was performed according to the suggestions of GuangFeng Zhao. This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang province, China (Grant No. 2009c03012-4).

Footnotes

Yangyan Jiang, Wenlu Li and Xin He contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YJ WL and XH were involved in data preparation. XH and HZ performed data analysis. XH, FJ, and ZC contributed to manuscript writing and the paper revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yangyan Jiang, Email: yangyanjiang11@163.com.

Wenlu Li, Email: wenlu256@gmail.com.

Xin He, Email: 21118135@zju.edu.cn.

Hongbo Zhang, Email: HongboZhang11@163.com.

Fangzhen Jiang, Email: fzj198727@163.com.

Zhigang Chen, Email: pridechen@126.com.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):104–17. doi: 10.3322/caac.21220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM. Molecular origins of cancer: molecular basis of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(25):2449–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodgson DC, Fuchs CS, Ayanian JZ. Impact of patient and provider characteristics on the treatment and outcomes of colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(7):501–15. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.7.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aranha O, Benson AB., 3rd Adjuvant therapy for colon cancer. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9(5):415–21. doi: 10.1007/s11894-007-0052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ailles LE, Weissman IL. Cancer stem cells in solid tumors. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2007;18(5):460–6. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rich JN, Bao S. Chemotherapy and cancer stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(4):353–5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fulda S, Pervaiz S. Apoptosis signaling in cancer stem cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42(1):31–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coco C, Zannoni GF, Caredda E, Sioletic S, Boninsegna A, Migaldi M, et al. Increased expression of CD133 and reduced dystroglycan expression are strong predictors of poor outcome in colon cancer patients. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2012;31:71. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-31-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang SS, Han ZP, Jing YY, Tao SF, Li TJ, Wang H, et al. CD133(+)CXCR4(+) colon cancer cells exhibit metastatic potential and predict poor prognosis of patients. BMC Med. 2012;10:85. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445(7123):106–10. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Peschle C, et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2006;445(7123):111–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shmelkov SV, Butler JM, Hooper AT, Hormigo A, Kushner J, Milde T, et al. CD133 expression is not restricted to stem cells, and both CD133+ and CD133- metastatic colon cancer cells initiate tumors. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(6):2111–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI34401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker L, Huang Q, Mashimo H. Immunostaining of Lgr5, an intestinal stem cell marker, in normal and premalignant human gastrointestinal tissue. Sci World J. 2008;8:1168–76. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu HC, Liu YS, Tseng KC, Hsu CL, Liang Y, Yang TS, et al. Overexpression of Lgr5 correlates with resistance to 5-FU-based chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Yamamoto Y, Sakamoto M, Fujii G, Tsuiji H, Kenetaka K, Asaka M, et al. Overexpression of orphan G-protein-coupled receptor, Gpr49, in human hepatocellular carcinomas with beta-catenin mutations. Hepatology. 2003;37(3):528–33. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McClanahan T, Koseoglu S, Smith K, Grein J, Gustafson E, Black S, et al. Identification of overexpression of orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR49 in human colon and ovarian primary tumors. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5(4):419–26. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.4.2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uchida H, Yamazaki K, Fukuma M, Yamada T, Hayashida T, Hasegawa H, et al. Overexpression of leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 in colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(7):1731–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01571.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanese K, Fukuma M, Yamada T, Mori T, Yoshikawa T, Watanabe W, et al. G-protein-coupled receptor GPR49 is up-regulated in basal cell carcinoma and promotes cell proliferation and tumor formation. Am J Pathol. 2008;173(3):835–43. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ziskin JL, Dunlap D, Yaylaoglu M, Fodor IK, Forrest WF, Patel R, et al. In situ validation of an intestinal stem cell signature in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2013;62(7):1012–23. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17(24):2815–34. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19981230)17:24<2815::AID-SIM110>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yusuf S, Peto R, Lewis J, Collins R, Sleight P. Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomized trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1985;27(5):335–71. doi: 10.1016/S0033-0620(85)80003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu XS, Xi HQ, Chen L. Lgr5 is a potential marker of colorectal carcinoma stem cells that correlates with patient survival. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:244. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saigusa S, Inoue Y, Tanaka K, Toiyama Y, Matsushita K, Kawamura M, et al. Clinical significance of LGR5 and CD44 expression in locally advanced rectal cancer after preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Int J Oncol. 2012;41(5):1643–52. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valladares-Ayerbes M, Blanco-Calvo M, Reboredo M, Lorenzo-Patino MJ, Iglesias-Diaz P, Haz M, et al. Evaluation of the adenocarcinoma-associated gene AGR2 and the intestinal stem cell marker LGR5 as biomarkers in colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(4):4367–87. doi: 10.3390/ijms13044367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi H, Ishii H, Nishida N, Takemasa I, Mizushima T, Ikeda M, et al. Significance of Lgr5(+ve) cancer stem cells in the colon and rectum. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(4):1166–74. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1373-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takeda K, Kinoshita I, Shimizu Y, Matsuno Y, Shichinohe T, Dosaka-Akita H. Expression of LGR5, an intestinal stem cell marker, during each stage of colorectal tumorigenesis. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(1):263–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng CLL, Liang Y, Hu JJ, Wang J, Jiang B, Wang XY. Higher expression of Lgr5 predicts poor prognosis in human colorectal cancer. Modern Digestion & Intervention. 2010;15(5):284–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.WG Bao YC. Detection of cancer stem marker, Lgr5, in colorectal cancer. Lin Chuang Jian Yan Za Zhi. 2012;30(9):691–3.

- 30.Gao FJ, Chen JY, Wu HY, Shi J, Chen M, Fan XS, et al. Lgr5 over-expression is positively related to the tumor progression and HER2 expression in stage pTNM IV colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(4):1572–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He S, Zhou H, Zhu X, Hu S, Fei M, Wan D, et al. Expression of Lgr5, a marker of intestinal stem cells, in colorectal cancer and its clinicopathological significance. Biomed Pharmacother. 2014;68(5):507–13. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Z, Dai W, Jiang L, Cheng Y. Over-expression of LGR5 correlates with poor survival of colon cancer in mice as well as in patients. Neoplasma. 2014;61(2):177–85. doi: 10.4149/neo_2014_016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van der Flier LG, Sabates-Bellver J, Oving I, Haegebarth A, De Palo M, Anti M, et al. The intestinal Wnt/TCF signature. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(2):628–32. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Segditsas S, Sieber O, Deheragoda M, East P, Rowan A, Jeffery R, et al. Putative direct and indirect Wnt targets identified through consistent gene expression changes in APC-mutant intestinal adenomas from humans and mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(24):3864–75. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]