Highlight

CO2 supply to Rubisco can involve diffusive CO2 fluxes or a CO2 concentrating mechanism. The mechanisms involve CO2 loss in photorespiration or by leakage, respectively.

Key words: Aquaporins, bicarbonate, carbon concentrating mechanisms, C4, carbon dioxide, crassulacean acid metabolism, leakage, lipid bilayer, permeability.

Abstract

It is difficult to distinguish influx and efflux of inorganic C in photosynthesizing tissues; this article examines what is known and where there are gaps in knowledge. Irreversible decarboxylases produce CO2, and CO2 is the substrate/product of enzymes that act as carboxylases and decarboxylases. Some irreversible carboxylases use CO2; others use HCO3 –. The relative role of permeation through the lipid bilayer versus movement through CO2-selective membrane proteins in the downhill, non-energized, movement of CO2 is not clear. Passive permeation explains most CO2 entry, including terrestrial and aquatic organisms with C3 physiology and biochemistry, terrestrial C4 plants and all crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) plants, as well as being part of some mechanisms of HCO3 – use in CO2 concentrating mechanism (CCM) function, although further work is needed to test the mechanism in some cases. However, there is some evidence of active CO2 influx at the plasmalemma of algae. HCO3 – active influx at the plasmalemma underlies all cyanobacterial and some algal CCMs. HCO3 – can also enter some algal chloroplasts, probably as part of a CCM. The high intracellular CO2 and HCO3 – pools consequent upon CCMs result in leakage involving CO2, and occasionally HCO3 –. Leakage from cyanobacterial and microalgal CCMs involves up to half, but sometimes more, of the gross inorganic C entering in the CCM; leakage from terrestrial C4 plants is lower in most environments. Little is known of leakage from other organisms with CCMs, though given the leakage better-examined organisms, leakage occurs and increases the energetic cost of net carbon assimilation.

Introduction

The textbook equations for oxygenic photosynthesis and for dark respiration have CO2 as, respectively, the inorganic C substrate and the inorganic C product. This is the case for the core autotrophic carboxylase of oxygenic photosynthetic organisms, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase (Rubisco), with CO2 as its inorganic carbon substrate, and for the decarboxylases of dark respiration with CO2 as their inorganic C product (Raven, 1972a; Table 5.2 of Raven, 1984; Table 3 of Raven, 1997a). Add to this the Overton prediction over a century ago that CO2 has a high permeability in lipid bilayers (see Endeward et al., 2014) and it appears at first sight that the textbook equations describe not just the inorganic C substrate for photosynthesis and inorganic C product of dark respiration, but also the inorganic C species crossing cell membranes between the external environments and intracellular sites of inorganic C consumption and production.

However, it is clear that this picture is significantly over-simplified in (at least) two ways. One is that we now know of CO2-permeable channels (a subset of the aquaporins, and analogues) in some cell membranes, and there is considerable debate as to their functional significance if the CO2 permeability of the lipid bilayer is very high (Boron et al., 2011; Itel et al., 2012; Endeward et al., 2014; Kai and Kaldendorf, 2014). The second over-simplification is that there are known CO2 concentrating mechanisms (CCMs), involving active transport of some inorganic C species (or H+) and/or C4 or crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) biochemistry, accounting for about half of global primary productivity. This assertion is based on the global net primary productivity values of 56 Pg C per year on land and 49 Pg C per year in the ocean (Field et al., 1998), the assumption that the ratio of global C4 gross primary productivity (almost all terrestrial) to total gross primary productivity, i.e. 0.23 (Still and Berry, 2003), also applies to net primary productivity, and the assumption that not less than 0.8 of the marine global net primary productivity is carried out by organisms with CCMs (Raven et al. 2012, 2014; Raven and Beardall, 2014). These assumptions give a total CCM-based global net primary productivity of (0.23×56) + (0.8×49) or 52 Pg C per year out of a total of 105 Pg C per year global net primary productivity.

CCMs necessarily involve an energy input to generate a net flux of inorganic C from the environment with a relatively low CO2 concentration to the active site of Rubisco where a higher steady-state CO2 concentration is maintained during photosynthesis. This means that the direction of the CO2 free energy gradient (inside concentration > outside) is the opposite of that for photosynthesis with C3 physiology and biochemistry (inside < outside). Accordingly, in an organism expressing a CCM, the high CO2 permeability of the pathway from the environment to Rubisco required for high rates of photosynthesis in organisms with C3 physiology and biochemistry would result in a decreased net rate of photosynthesis and increased energy requirement per net CO2 assimilated (Raven et al., 2014). The final result is an increased energy cost of CCMs relative to that of diffusive entry with C3 physiology and biochemistry.

Important progress in understanding bidirectional fluxes of inorganic carbon in an organism expressing a CCM has been made in a recent paper in the Journal of Experimental Botany (Eichner et al., 2015). Using the marine diazotrophic cyanobacterium Trichodesmium, this work combined two experimental approaches, membrane inlet mass spectrometry to distinguish CO2 from HCO3 – fluxes (Badger et al., 1994) and measurements of the natural abundance of 13C relative to 12C (Sharkey and Berry, 1985), with modelling. A very important conclusion is that internal cycling of inorganic C is significant for the natural isotope abundance of 13C:12C in the organism, and for cellular energy budgets. This commentary considers wider aspects of CCMs and of leakage of inorganic carbon from them, and how the findings of Eichner et al. (2015) might help further interpretation of data on other organisms, including eukaryotic algae and vascular plants.

Species of inorganic C involved in carboxylases and decarboxylases

All of the unidirectional decarboxylases examined (functioning far from thermodynamic equilibrium), i.e. those of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway, produce CO2 (Raven, 1972a,b). By analogy with such unidirectional decarboxylases, the product of glycine decarboxylase, the enzyme responsible for CO2 production in the photorespiratory carbon oxidation cycle, is also very likely to be CO2.

Enzymes that function in vivo sufficiently close to thermodynamic equilibrium, and hence can function as carboxylases and decarboxylases, both consume and produce CO2 (Table 5.2 of Raven, 1984; Häusler et al., 1987; Jenkins et al., 1987; Table 3 of Raven, 1997a). Significantly for the present article, the decarboxylase function of three of these enzymes (phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase; NAD+ malic enzyme; NADP+ malic enzyme) is involved in the decarboxylation step of C4 and CAM photosynthesis (Jenkins et al., 1987).

Among unidirectional carboxylases, operating far from thermodynamic equilibrium, a number use CO2 as the inorganic C substrate (Table 5.2 of Raven, 1984; Häusler et al., 1987; Jenkins et al., 1987; Table 3 of Raven, 1997a; Firestyne et al., 2009). Importantly for the present article, these CO2-consuming carboxylases include Rubisco, the core carboxylase of all oxygenic photosynthetic organisms, as well as the 5-aminoimidazole ribonucleotide carboxylase required for purine synthesis.

Finally, some unidirectional carboxylases consume HCO3 – (Table 5.2 of Raven, 1984; Table 3 of Raven, 1997a). One of these is phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, an essential anaplerotic enzyme in almost all oxygenic photosynthetic organisms (Table 4 of Raven, 1997a) as well as the ‘C3 + C1’ carboxylase of organisms with C4 photosynthesis (with the exception of the ulvophycean marine macroalga Udotea flabellum: see Raven, 1997a) and with CAM photosynthesis. A possible alternative ‘C3 + C1’ carboxylase for C4 and CAM photosynthesis is pyruvate carboxylase, which also uses HCO3 – as the inorganic C substrate (Table 5.2 of Raven, 1984; Table 3 of Raven, 1997a). Other carboxylases using HCO3 – include acetyl CoA carboxylase used in the synthesis of long-chain fatty acids, and carbamoyl phosphate synthase, essential for citrulline, and hence arginine, synthesis (Table 4 of Raven, 1984; Table 3 of Raven, 1997a).

CO2 permeability of lipid bilayers and the role of CO2-conducting aquaporins and analogous protein pores

There is still significant uncertainty as to the mechanism of CO2 permeation of biological membranes (Boron et al., 2011; Itel et al., 2012; Endeward et al., 2014; Kai and Kaldendorf, 2014). A particular problem is the role of proteinaceous CO2 channels if the intrinsic CO2 permeability of the lipid bilayer is very high, although there is evidence of increased photosynthesis and growth in terrestrial C3 plants expressing CO2-transporting aquaporins (Uehlein et al., 2003, 2008; Heckwolf et al., 2011) The most convincing evidence for the role of aquaporins in terrestrial C3 plants comes from Hanba et al. (2004) and Tsuchihira et al. (2010). Table 1 shows the permeability coefficient for CO2 of planar lipid bilayers of various compositions, and for the plasmalemma vesicles derived from high and low CO2-grown Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. In all three cases attempts were made to eliminate the influence of diffusion boundary layers on each side of the membrane on the measured permeability.

Table 1.

Permeability coefficient for CO2 in planar lipid bilayers and plasmalemma vesicles, corrected as far as possible for limitation by aqueous diffusion boundary layers

Also shown are the modelled ‘optimum’ or ‘maximum’ (for functioning in the CCM) CO2 permeability of the wall of cyanobacterial carboxysomes and/or the estimated CO2 permeability of the wall of cyanobacterial carboxysomes.

| Experimental system |

CO

2

permeability

m s –1 |

References |

|---|---|---|

| Planar lipid bilayer composed of 1:1 egg lecithin:cholesterol. 22–24 °C | 3.5±0.4.10–3 (standard error) | Gutknecht et al. (1977) |

| Plasmalemma vesicles of C. reinhardtii grown photolithtrophically in media with high low (350 μmol mol–1 total gas) and high (50 mmol mol–1 total gas) CO2 for growth.? °C | 0.76±0.03–1.49±0.2.10–5 (± standard error; low CO2-grown cells) 1.21±0.01–1.8±0.17.10–5 (± standard error; high CO2- grown cells) |

Sültemeyer and Rinast (1996) |

| Planar lipid bilayer composed of (i) pure diphytanoyl-phosphatidyl choline (ii) 3:2:1 cholesterol: diphytanoyl-phosphatidyl choline: egg sphingomyelin, and (iii) mixture of lipids mimicking the red cell plasmalemma.? °C | ≥3.2±1.6.10–2(not clear what ± refers to; ≥3.2 refers to all three membrane compositions) |

Missner et al. (2008) |

| Estimate of upper limit on CO2 permeability of cyanobacterial carboxysome wall consistent with CCM function. | 10–7–2.5.10–6 | Reinhold et al. (1987, 1991) |

| Estimate of CO2 permeability of the carboxysome wall of Synechococcus assuming all of the limitation of CO2 efflux from carboxysomes is in the carboxysome wall. 30 °C | 2.2.10–7 (no estimates of error given) | Salon et al. (1996a,b), Salon and Canvin (1997) |

| Estimate of CO2 permeability of the carboxysome wall in Anabaena variabilis assuming all of the limitation to CO2 efflux from carboxysomes is in the carboxysome wall. 30 °C | 2.8±0.8.10–7 (standard error, n=9) | McGinn et al. (1997) |

| Estimate of ‘optimal’ CO2 permeability of cyanobacterial carboxysome wall from CCM model. | 10–5 | Mangan and Brenner (2014) |

| CO2 permeability of carboxysome wall in Prochloroccus estimated from a model of CCM function. | 10–7 | Hopkinson et al. (2014) |

| Estimate of CO2 permeability of the carboxysome wall in Prochlorococcus assuming all of the limitation to CO2 efflux from carboxysomes is in the carboxysome wall. | 10–6 | Hopkinson et al. (2014) |

Method for all three data sets involves measurement of inorganic carbon fluxes, expressed as CO2, under a known CO2 concentration difference across the membrane across planar membrane bilayers (Gutknecht et al., 1997; Missner et al., 2008) or plasmalemma vesicles of Chlamydomonas (Sültemeyer and Rinast, 1996). Carbonic anhydrase was added to both sides of the membrane to minimize the gradient of CO2 across the aqueous diffusion boundary layers on each side of the membrane.

CO2 entry in organisms lacking a biophysical CCM

The classic example of these is the C3 vascular land plants. It is now clear that CO2 is the species of inorganic carbon entering the cells from the cell wall (Colman and Espie, 1985; Espie and Colman, 1986; Espie et al., 1986; Evans et al., 2009; Maberly, 2014). The assumption is that terrestrial C4 and CAM vascular plants also rely on CO2 entry from the cell wall to the cytosol where carbonic anhydrase equilibrates CO2 with HCO3 –, the inorganic C substrate for PEPc (Colman and Espie, 1985; Nelson et al., 2005).

For C3 plants the transport of CO2 from the outside of the cell wall to Rubisco involves diffusion of CO2 across the plasmalemma and across the outer and inner chloroplast membranes and, in the aqueous phase, through the cell wall, the cytosol and the stroma (Colman and Espie, 1985). It is implicitly assumed that there is no carbonic anhydrase in the cell wall (Raven and Glidewell, 1981; Colman and Espie, 1985) of C3 plants, though there seems to be no experimental evidence demonstrating this. Carbonic anhydrases could equilibrate CO2 and HCO3 – in the cytosol and stroma and so enlist the predominant (at the pH of the cytosol and stroma) inorganic species, HCO3 –, in CO2 transport across these aqueous phases, with the required H+ flux carried inwards by protonated buffers with a return flux outwards of the deprotonated buffers (Raven and Glidewell, 1981; Colman and Espie, 1985; Evans et al., 2009; Niinemets et al., 2009; Tazoe et al., 2009, 2011). There is very significant interspecific variation in the magnitude of the mesophyll conductance (= permeability) of C3 seed plants (Evans et al., 2009; Niinemets et al., 2009; Tazoe et al., 2009; see Table 2).

Table 2.

Permeability coefficient (‘mesophyll conductance’) for CO2 entry for the pathway from the outside of the external aqueous diffusion boundary layer to Rubisco in C3 biochemistry

No data seem to be available for the corresponding CO2 movement to PEPc in C4 or CAM biochemistry.

| Category of plant: flowering plant, hornwort, or liverwort | Mesophyll permeability m s–1 |

|---|---|

| Herbaceous dicotyledonous flowering plant | 2.16±0.32.10–4 (standard error, n not clear) |

| Herbaceous monocotyledonous flowering plant | 2.24±0.29.10–4 (standard error, n not clear) |

| Woody deciduous dicotyledonous flowering plant | 1.05±0.12.10–4 (standard error, n not clear) |

| Woody evergreen dicotyledonous flowering plant | 0.85±0.08.10–4 (standard error, n not clear) |

| Hornwort | 1.75.10–4 (no statistics provided by Meyer et al., 2008) |

| Unventilated liverwort | 1.90±0.15.10–4 (standard deviation, n=3 |

| Ventilated liverwort | 0.80±0.04.10–4 (standard deviation, n=3) |

Conversion of photosynthetic rates for the plants on a projected leaf area basis (from Table 1 of Warren, 2008) to the area of mesophyll cells exposed to the intercellular gas space uses a ratio of 25 m2 m2 mesophyll cells exposed to the intercellular gas space projected leaf area (from pp. 380–381of Nobel, 2005). Conversion of the difference in CO2 concentration between the outside of the cell wall to the chloroplast stroma expressed in terms of atmospheric mol fraction (μmol CO2 mol–1 total atmospheric gas) from Table 1 of Warren (2008) to mmol CO2 dissolved in each m3 of leaf water uses a conversion factor of 1 mmol CO2 m–3 dissolved in leaf water for each 20.4 μmol CO2 mol–1 total atmospheric gas (from pp. 377 and 384 of Nobel, 2005). For a ventilated thalloid liverwort the ratio of 9 m2 mesophyll cells exposed to the intercellular gas space per m2 projected thallus area (Green and Snelgar, 1982), and for a hornwort or and unventilated liverwort thallus the ratio is 1 (Green and Snelgar, 1982), with other data from Meyer et al. (2008).

Turning to submerged aquatic organisms, a number have CO2 entry followed by diffusive flux to Rubisco, resembling C3 land plants, although aquatic vascular plants lack stomata. These organisms include a number of freshwater and marine algae, aquatic bryophytes, and freshwater vascular plants (Raven, 1970; MacFarlane and Raven, 1985, 1989, 1990; Kübler et al., 1999; Sherlock and Raven, 2001; Maberly and Madsen, 2002; Raven et al., 2005; Maberly et al., 2009; Maberly, 2014). While these organisms share some of the physiological characteristics found in organisms with CCMs, e.g. the absence of a competitive interaction between CO2 and O2 in photosynthetic gas exchange (Kübler et al., 1999; Sherlock and Raven, 2001; Maberly et al., 2009), the overall influence of environmental factors points to diffusive CO2 entry.

CO2 entry in organisms expressing a biophysical CCM

A biophysical CCM that involves diffusive CO2 entry was first proposed by Walker et al. (1980; see Briggs, 1959) for ecorticate giant internodal cells of freshwater green algal macrophytes of the Characeae growing in relatively alkaline waters. The localized active efflux of H+ across the plasmalemma causes a localized decrease in pH in the cell wall and diffusion boundary layer, to approximately 2 pH units below that in the medium. As HCO3 – diffuses into the acid zone, the equilibrium CO2:HCO3 – increases 100-fold, as does the rate of HCO3 – conversion to CO2 in the absence of carbonic anhydrase (Walker et al., 1980). Subsequently, expression of carbonic anhydrase in the acid zones was demonstrated, further increasing the rate of HCO3 – to CO2 conversion (Price et al., 1985; Price and Badger, 1985). Intracellular acid-base regulation requires alkaline zones between the acid zones. This mechanism also occurs in some freshwater flowering plants where the acid zone is on the abaxial leaf surface and the alkaline zone is on the adaxial leaf surface (Maberly and Madsen, 2002). The high CO2 concentration generated in the acid zones can, after crossing the plasmalemma by diffusion, give an internal CO2 concentration rather less than that in the acid zone but still sufficient to constitute a CCM with the CO2 concentration inside the cell higher than that in the bulk medium (Walker et al., 1980; Price et al., 1985; Price and Badger, 1985). As well as CO2 leakage from the acid zones to the bulk medium, CO2 could also leak from the cytosol back to the bulk medium through the alkaline zones.

A similar mechanism is thought to occur in many marine macrophytes as a mechanism of using external HCO3 – (Raven and Hurd, 2012). However, the evidence for this is (a) inhibition of external HCO3 – use by pH buffers that, ex hypothesis, eliminate the acid zones, (b) inhibition of external carbonic anhydrase using a membrane-impermeant inhibitor as well as, in some cases, (c) showing that photosynthesis is not decreased by inhibitors of one group of plasmalemma HCO3 – transporters (Raven and Hurd, 2012). There have been no direct demonstrations of the acid zones in macroalgae because, although they can be visualized when they occur in the freshwater Characeae and vascular macrophytes, they must (if they exist!) occupy smaller areas in marine macro algae and in seagrasses (Raven and Hurd, 2012).

An analogous mechanism involves external HCO3 – entry at the plasmalemma and across the chloroplast envelope membranes, not necessarily giving higher internal than external concentration, with HCO3 – entry to the thylakoid lumen via (ex hypothesis) HCO3 –-transporting channels (Raven, 1997b; Jungnick et al., 2014; Raven et al., 2014). The low pH of the thylakoid lumen, with the presence (at least in Chlamydomonas) of a carbonic anhydrase, gives a rate of CO2 production, and an equilibrium CO2 concentration, similar to that in the extracellular acid zones of some freshwater macrophytes (Raven, 1997b; Moroney and Ynalvez, 2007; Jungnick et al., 2014; Raven et al., 2014). The final step in the CCM is diffusion of the CO2 from the lumen to the stroma, and especially to the pyrenoid where most of the Rubisco occurs in Chlamydomonas (Raven, 1997b; Raven et al., 2014). CO2 leakage could occur from the pyrenoid back to the bulk medium.

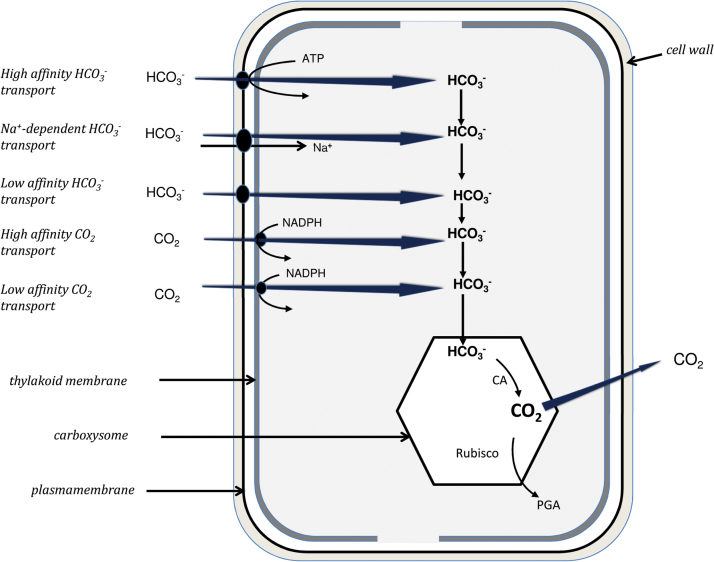

Energetically downhill entry of CO2 as part of a CCM occurs in cyanobacteria, although without localized surface acidification (see data of Maeda et al., 2002, and models of Mangan and Brenner, 2014; Eichner et al., 2015) (Fig. 1). Three further essential components are, first, active HCO3 – influx at the plasmalemma, and the unidirectional conversion of CO2 to HCO3 – energized by the NDHI4 component of cyclic electron flow round photosystem I at the outer surface of the thylakoid membrane. Second, the carboxysomes, containing Rubisco and carbonic anhydrase, whose protein subunit walls probably have a limited permeability to CO2 (see estimates in Table 1). The cytosolic HCO3 – from these two sources enters carboxysomes through pores also allowing permeation of anions (Raven, 2006) and H+ (Menon et al., 2010) or, perhaps, OH–. Finally, HCO3 – in the carboxysome lumen is acted on by carbonic anhydrase, producing CO2 that is (mainly) consumed by Rubisco in the carboxysome, though some CO2 could leak to the cytosol. The extent of CO2 leakage through the carboxysomal wall is likely to be significant, even with a low CO2 permeability coefficient across the carboxysomal wall with its positively charged pores, because of the large CO2 accumulation factor (two to three orders of magnitude) in the carboxysome lumen relative to the cytosol during photosynthesis (Eichner et al., 2015). Modelling by Mangan and Brenner (2014) finds that the optimal carboxysome wall permeability coefficient for CO2 for maximal CO2 accumulation in the carboxysome lumen is around 10–5 m s–1.

Fig. 1.

A schematic model for inorganic carbon transport, and CO2 accumulation and leakage in cyanobacteria. Low affinity transport systems are shown in grey and high affinity systems are shown in black, and are found at the plasmalemma and/or thylakoid membrane. Transporters whose characteristics are unknown are shown in white. Redrawn after Fig. 1 of Price et al. (2002), Badger and Price (2003), and Giordano et al. (2005). (Price et al. 2002. Modes of active inorganic carbon uptake in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC7942. Functional Plant Biology 29, 131–149. CSIRO PUBLISHING (http://www.publish.csiro.au/nid/102/paper/PP01229.htm). (Badger and Price 2003. CO2 concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria: molecular components, their diversity and evolution. Journal of Experimental Botany 54, 609–622). (Giordano et al. 2005. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in algae: mechanisms, environmental modulation, and evolution. Annual Review of Plant Biology 6, 99–131).

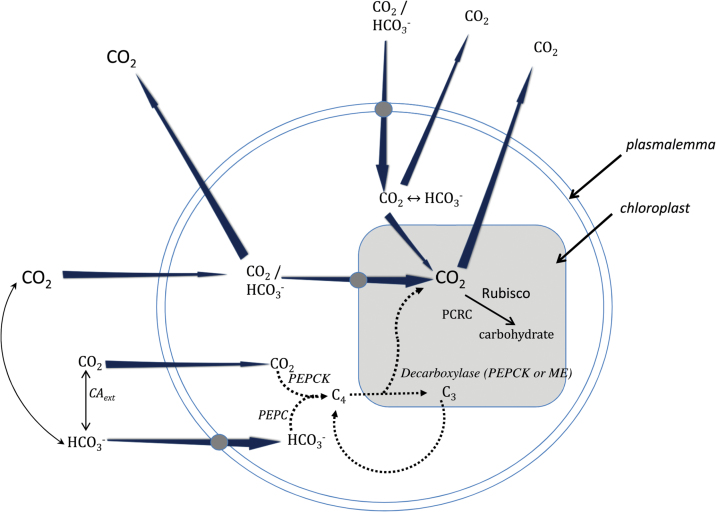

Hopkinson et al. (2011) and Hopkinson (2014) propose a general similar mechanism for diatoms, with active HCO3 – influx at the plasmalemma (Nakajima et al., 2013) and parallel non-energized CO2 influx (Fig. 2). These models involve cytosolic carbonic anhydrase to convert the CO2 to the equilibrium concentration of HCO3 –, with active HCO3 – uptake by chloroplasts. This latter step has not yet been identified in diatoms.

Fig. 2.

A schematic model for inorganic carbon transport, and CO2 accumulation and leakage in eukaryotic algal cells. The model incorporates the possibilities for DIC transport at the plasmalemma and/or chloroplast envelope as well as a putative C4-like mechanism. Active transport processes (shown by the shaded boxes) can be of CO2 or HCO3−. No attempt has been made to show the roles of the various internal CAs in the different compartments. For this the reader is referred to Giordano et al. (2005). Redrawn after Giordano et al. 2005. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in algae: mechanisms, environmental modulation, and evolution. Annual Review of Plant Biology 6, 99–131.

Is there a role for active transport of CO2? The occurrence of a CO2-stimulated ATPase from the ‘microsomal’ fraction (= plasmalemma?) of the freshwater green (chlorophycean) alga Eremosphaera viridis, the predominance of CO2 uptake in photosynthesis in this alga, and the electroneutrality of CO2 uptake (ruling out cation symport), is consistent with CO2 uptake by primary active transport (Rotatore et al., 1992; Deveau et al., 1998; Huertas et al., 2000a; Deveau et al., 2001). No other CO2 transporters that could reasonably function in active CO2 transport are known. Accordingly, the possibility that other eukaryotes depend on a mechanism of the kind suggested by Beardall (1981) and Hopkinson et al. (2011), involving passive CO2 entry at the plasmalemma and active HCO3 – transport into the chloroplasts, cannot be ruled out for algae with a CCM and dominant CO2 uptake, e.g. acidophilic eukaryotic algae, unless it has been shown that there is no HCO3 – transporter at the chloroplast envelope. Rotatore and Colman (1990) showed that isolated chloroplasts of Chlorella ellipsoidea could take up HCO3 – by active transport, but had no active CO2 uptake; however, the HCO3 – influx uptake by isolated chloroplasts is less than that at the plasmalemma on a per cell basis (Rotatore and Colman, 1991a,b). Rotatore and Colman (1991c) suggest that there is active uptake of CO2 at the plasmalemma of Chlorella saccharophila and C. ellipsoidea, although the possibility suggested by Beardall (1981) and Hopkinson et al. (2011) of passive CO2 followed by active entry of inorganic C into chloroplasts cannot be ruled out.

HCO3 – entry in organisms expressing a biophysical CCM

Use of HCO3 – is indicated by more rapid photosynthesis than can be accounted for by the uncatalysed rate of HCO3 – to CO2 conversion (Briggs, 1959). The ‘direct’ use of HCO3 – involves influx of the anion at the plasmalemma, as compared with the ‘indirect’ use by external conversion to CO2 as described in the previous section (see Briggs, 1959). The physiological methods of demonstrating direct use of HCO3 – involve the known absence, or inhibition, of external carbonic anhydrase(s). In cyanobacteria (Eichner et al., 2015; Hopkinson et al., 2014) and eukaryotic algae such as diatoms (Nakajima et al., 2013), HCO3 – entry has been shown by physiological methods, and also by molecular genetic techniques, including ectopic expression and tests of functionality of the HCO3 – transporter gene. The processes in cyanobacteria (Mangan and Brenner, 2014; Eichner et al., 2015) (Fig. 1) and diatoms (Hopkinson et al., 2011; Hopkinson, 2014) (see Fig. 2) have been recently modelled.

In other algae HCO3 – entry has been shown by physiological methods, including the absence of inhibition of photosynthesis by pH buffers or by inhibition of external carbonic anhydrase, and inhibition by inhibitors of anion exchange proteins (Raven and Hurd, 2012). In some cases, e.g. the eustigmatophycean marine microalga Nannochloropsis gaditana, all of the inorganic carbon entering in the CCM involves direct entry of HCO3 – (e.g. Munoz and Merrett, 1989; Huertas and Lubián, 1997; Huertas et al., 2000b, 2002). In most cases, there is entry of both CO2 and HCO3 – in CCMs (Korb et al., 1997; Tortell et al., 1997; Burkhardt et al., 2001; Giordano et al., 2005; Rost et al., 2006a,b, 2007; Tortell et al., 2008) and, in a few cases (see above) only CO2 enters in algae with CCMs.

Isolated, metabolically active chloroplasts of some green algae with CCMs show CO2 and HCO3 – uptake into the chloroplasts as well as into whole cells (Amoroso et al., 1998, van Hunnik et al., 2002, Giordano et al., 2005, and references therein). Yamano et al. (2015) show co-operative expression of the plasmalemma HCO3 – HLA3 ABC transporter and the chloroplast envelope LCIA formate/nitrite transporter homologue (Wang and Spalding, 2014) in C. reinhardtii. LCIA is probably a HCO3 – channel (Wang and Spalding, 2014; Yamano et al. 2015); Wang and Spalding (2014) point out that such a channel could not act to accumulate HCO3 – in the stroma relative to the cytosol since the electrical potential difference across the chloroplast envelope is stroma negative relative to the cytosol.

Leakage from the intracellular inorganic C pool of CCMs

Significant attention has been paid to leakage of CO2 from terrestrial C4 plants; this has been thoroughly reviewed by Kromdijk et al. 2014 (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S1, available at JXB online). For typical C4 anatomy with mesophyll cells with intercellular gas spaces and a single bundle sheath layer with limited exposure to intercellular gas spaces and, in some cases, a suberin (mestome) sheath that could further limit CO2 leakage, Kromdijk et al. (2014) give an excellent critique of the methods used to determine the leakiness to CO2 (CO2 efflux as a fraction of gross CO2 influx) and list their outcomes. These are 14CO2 labelling to determine the size of the bundle sheath inorganic carbon pool (and hence CO2 efflux) or to directly estimate CO2 efflux, the deviation of the quantum yield of CO2 assimilation from the value predicted from biochemistry assuming no CO2 leak, and the natural abundance of stable carbon isotopes in the organic matter of the plant (determined by destructive sampling, or from online measurements of CO2 before and after gas flow over photosynthesizing plants) relative to that of source CO2. All of these methods have problems (Kromdijk et al., 2014; von Caemmerer et al., 2014). The values for leakiness vary between –0.03–0.70. For the much less common case of terrestrial single-cell C4 photosynthesis, the leakiness is similar to that for typical C4 anatomy determined by similar methods (King et al., 2012). The permeability of the bundle sheath cells for CO2 (1.6–4.5.10–6 m s–1: Table 4), derived from the CO2 efflux from the pool accumulated by the CCM and the driving force of the difference in CO2 concentration between the CCM pool and the medium, is at least an order of magnitude higher than the permeabilities for cyanobacteria (Table 4). However, the bundle sheath permeability is two orders of magnitude less than the mesophyll permeability in C3 plants (Table 2).

Table 3.

Leakage of inorganic C from CCMs as a fraction of the inorganic C pumped into the intracellular pool for in terrestrial C4 flowering plants, hornworts, eukaryotic algae, and cyanobacteria

Values are from Supplementary Table S1 except for C4 terrestrial flowering plants where the more detailed data in Table 1 of Kromdijk et al. (2014) was used. For C3 plants, leakage of CO2 from photorespiration is <0.2 of gross CO2 fixation (see text).

| Organism | Range of CO2 leakage estimates as a fraction of gross CO2 entry, from Supplementary Table S1 | Mean leakage from estimates in Supplementary Table S1 or (C4 terrestrial flowering plants) the more detailed data in Table 1 of Kromdijk et al. (2014) |

|---|---|---|

| C4 terrestrial flowering plants | –0.03–0.70 | 0.260±0.108 (standard deviation, n=20)1 |

| Hornworts with CCMs | 0.170, 0.304, 0.31 | 0.263±0.066 (standard deviation, n=3)2 |

| Eukaryotic algae | 0.01–0.80 | 0.36±0.16 (standard deviation, n=14): using results from MIMS only.3 |

| Cyanobacteria | 0.09–0.78 | 0.407±0.214 (standard deviation, n=5): using results from MIMS only.3 |

1Calculated from sum of means of ranges in Table 1 of Kromdijk et al. (2014), using data from all methods of estimation. Where values are given for more than one irradiance the value from the highest irradiance was used. The theroretically impossible value of –0.03 of leakage obtained by the quantum yield methods was retained rather than being rounded to zero; this made no difference to the outcome.

2Estimates from C isotope method, acknowledging that the pyrenoid-based CCM in hornworts may be subject to over-estimation as a result of internal recycling discussed for eukaryotic algae (see Wang and Spalding, 2014).

3Estimates from the C isotope method for leakage from a cyanobacterium in excess of 1.0 are theoretically impossible; these and other very high values obtained by this method for the cyanobacteria, are not given here. Possible reasons for these very high values are discussed by Eichner et al. (2015). For eukaryotic algae an analogous over-estimate of leakage using the C isotope method to that suggested for cyanobacteria could also occur, at least in Chlamydomonas (Wang and Spalding, 2014), but in the case of the eukaryotic algae none of the leakage estimates from using the C isotope method in Supplementary Table S1 are higher than the highest estimates from the MIMS method.

Table 4.

Permeability coefficients, on a cell surface area basis, for CO2 and HCO3 – determined for efflux of inorganic carbon from the intracellular pool accumulated by CCMs in cyanobacteria and for the bundle sheath of C4 plants

| Organism | Inorganic carbon species |

Permeability coefficient m s–1 |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synechococcus (Cyanobacterium) | CO2 | 10–7 m s–1 (no estimates of errors given) | Badger et al. (1985) |

| Synechococcus | CO2 | 2.49±0.13.10–8 m s–1 (standard error, n=4) –3.36±0.14.10–8 m s–1 (standard error, n=18) | Salon et al. (1996a,b) |

| Synecchococcus 1 | HCO3 - | 1.47±0.23.10–9 m s–1 (standard error, n = 7) –1.84±0.17.10–9 m s–1 (standard error, n=7) | Salon et al. (1996a,b); Salon and Canvin (1997) |

| Anabaena variabilis (Cyanobacterium) | CO2 | 9.8±1.5.10–8 m s–1 (standard error, n=10) | McGinn et al. (1997) |

| Anabaena variabilis 1 | HCO3 − | 7.6±0.9.10–9 m s–1 (standard error, n=7) | McGinn et al. (1997) |

| C4 terrestrial flowering plants (5 species) | CO2 | 1.6–4.5.10–6 m s–1 (no estimates of errors given) | Furbank et al. (1989) |

1The quantification of the efflux of HCO3 – is less direct than that of CO2 efflux. As mentioned by Salon et al. (1996b), the permeability coefficient for HCO3 – is a minimal value since the inside-negative electrical potential difference across the plasmalemma is not accounted for in the calculations.

Leakage of an increased fraction of the CO2 released into the bundle sheath by the biochemical CO2 pump at low light is thought to be a reason for the rarity of shade-adapted C4 plants (see Bellasio and Griffiths, 2014). Bellasio and Griffiths (2014) point out that there is an ontogenetic shading of older leaves in high light-adapted C4 plants, and that up to 50% of C4 crop photosynthesis occurs in shaded leaves, and investigated CO2 leakage in shade-acclimated leaves of the sun-adapted Zea mays. They found that CO2 leakage as a fraction of PEPc activity (= biochemical CO2 pump) stayed constant with decreasing light, thus differing from expectation of a relative increase in leakage. The basis for the this constancy is a decreased PEPc activity relative to that of Rubisco, and fixation of an increased fraction of the CO2 generated from respiration in bundle sheath cells.

Less attention has been paid to leakage of CO2 from terrestrial CAM plants (Cockburn et al., 1979; Winter and Smith, 1996; Nelson et al., 2005; Nelson and Sage, 2008; Winter et al., 2015).

Cockburn et al. (1985) examined the shootless orchid Chiloschista usneoides where CAM occurs (in the absence of other photosynthetic structures) in the astomatous velameniferous root. The absence of stomata means that the usual terrestrial CAM method of diurnal closure of stomata decreasing CO2 leakage during deacidification and CO2 refixation by Rubisco is unavailable. Cockburn et al. (1985) showed that the intercellular CO2 concentration during deacidification is not significantly different from that of the surrounding atmosphere, while the intercellular CO2 concentration during dark acidification is lower than that of the surrounding atmosphere. While lower intercellular CO2 concentration in the deacidification phase than is the case of stomata-bearing CAM structures decreases the leakage of CO2 from intercellular gas spaces in the stomata-less roots, it also means that carboxylase activity of Rubisco is likely to be substantially below saturation, and the Rubisco oxygenase activity is likely to be significant.

For aquatic vascular plants with CAM there is also no possibility of stomatal limitation of leakage of CO2 produced during deacidification in the light. For isoetids there is very little loss from the possible leakage of CO2 from the astomatal, cuticularized, photosynthetic part of the leaf, and even loss from any lower, less cuticularized, part of the leaf might be limited or abolished by the high CO2 concentration in the surrounding sediment that contains mineralizing particulate organic matter derived by sedimentation from the plankton. The non-isoetid submerged aquatic CAM flowering plant Crassula helmsii also lacks the leakage-limiting stomatal closure mechanism of terrestrial Crassula spp. C. helmsii can show net CAM fixation from external CO2 in the dark and also net photosynthetic C3 CO2 assimilation from external CO2 in parallel with refixation of internal CO2 generated in deacidification from malic acid, with, presumably, implications for CO2 leakage (Newman and Raven, 1995; Maberly and Madsen, 2002; Klavsen and Maberly, 2010).

Of course, the great majority of aquatic primary producers carrying out almost all of the aquatic primary productivity involving CCMs do not express CAM. Essentially all of the work on leakage of CO2 from intracellular pools of the CCM in aquatic organisms comes from cyanobacteria and eukaryotic microalgae; very little is known of leakage of CO2 from algal macrophytes or submerged aquatic vascular macrophytes that concentrate CO2 by C4 metabolism or a biophysical CCM. Perhaps the clearest example of CO2 leakage comes from the work of Tchernov et al. (1997, 1998, 2003) using membrane inlet mass spectrometry (MIMS). This method gives estimates of changes in CO2 and O2 in solution, with the difference between the two (if the photosynthetic quotient is assumed to be 1) representing the HCO3 – flux, typically (see above) HCO3 – influx. Tchernov et al. (1997, 1998, 2003) found an increase in external O2 and also CO2, with the computed HCO3 – influx exceeding the organic carbon production rate computed from O2 production. Especially at high light, the HCO3 – influx can significantly exceed the rate of photosynthesis, with the ‘excess’ inorganic carbon lost as CO2 in (for example) the cyanobacterium Synechococcus and the eustigmatophycean eukaryotic alga Nannochloropsis (Tchernov et al., 1997, 1998, 2003). There are also cases of CO2 influx exceeding the organic C production, implying net HCO3 – efflux.

However, the general case with MIMS measurements is that of CO2 decrease, or at least no increase, in the light. Here the MIMS method can be used to estimate CO2 efflux in the light from the CO2 efflux immediately after the cessation of illumination (Badger et al., 1994; Salon et al., 1996a,b; Eichner et al., 2015; Table 3 and Supplementary Table S1, available at JXB online). Badger et al. (1994) found a leakage of not more than 0.1 of net photosynthesis in low inorganic carbon-grown cells of Synechococcus, while for low CO2 grown Chlamydomonas the corresponding leakage is 0.5 at low inorganic C and 0.1 at high inorganic C. Again using Synechococcus, Salon et al. (1996a,b) and Salon and Canvin (1997) were able to distinguish CO2 efflux from HCO3 – efflux immediately after darkening; the total inorganic C efflux in the presence of carbonic anhydrase was measured, as was the CO2 efflux under non-equilibrium conditions, and the difference is the HCO3 – efflux. The CO2 efflux was only 0.08 of the maximum CO2 influx, while the HCO3 – efflux was 0.45 of the maximum HCO3 – influx. The CO2 permeability coefficient determined from the measurements and expressed in terms of the plasmalemma area was 3.10–8 m s–1, while it was 1.6–2.5 m s–1 in terms of the carboxysome area (Tables 1, 14). The HCO3 – permeability coefficient expressed in terms of the plasmalemma area is at most 1.4–1.7.10–9 m s–1 (Table 4); the value is an upper limit because the inside-negative electrical potential component was not used in the calculation (Salon et al. 1996b; see also Ritchie et al. 1996).

In the case of Trichodesmium the leakage (CO2 efflux:gross inorganic carbon uptake) calculated using MIMS is 0.3–0.7 for two CO2 levels and with or without NO3 – (Eichner et al., 2015), as compared with values of 0.5–0.9 in previous work on this organism (see Kranz et al., 2009, 2010) (Table 3).

The other main method for estimating leakage of CO2 from aquatic organisms expressing a CCM is from natural abundance 13C/12C of particulate organic matter gained by photolithotrophic growth and of the 13C/12C of external inorganic carbon species (Sharkey and Berry, 1985; Eichner et al., 2015; Table 3 and Supplementary Table S1). This method is also used for estimating leakage of CO2 from terrestrial C4 plants (see above). Eichner et al. (2015) found a difference between the MIMS and the natural abundance 13C/12C estimates of leakage, with the latter method giving values of the 0.82 and 1.14. They point out that the values > 1 are theoretically impossible; Eichner et al. (2015) suggest kinetic fractionation between CO2 and HCO3 – in the cytosol and/or enzymatic fraction by the ‘energized, unidirectional carbonic anhydrase’ NDH-14 as possible causes of the very high leakage estimates. An analogous role might be played by the LCIA/LCIB system in C. reinhardtii (Wang and Spalding, 2014), so that estimates of leakage from carbon isotope ratios may be too high in Chlamydomonas and possibly in other eukaryotic algae as well. This possibility is acknowledged in Table 3 and Supplementary Table S1 (available at JXB online).

The mean value for the leakage determined by MIMS for cyanobacteria and eukaryotic algae in Supplementary Table S1 is, as indicated in Table 3, respectively 0.407±0.214 (standard deviation, n=5) and 0.36±0.16 (standard deviation, n=14). The mean values for hornworts with CCMs and C4 terrestrial flowering plants are 0.263±066 (standard deviation, n=3) and 0.260±0.106 (standard deviation, n=20), respectively. There is a trend (not significant) for lower fractional leakage in terrestrial C4 plants and hornworts than for cyanobacteria and eukaryotic algae.

As for C4 plants, so with cyanobacterial and algal CCMs: the prediction is an increasing fraction of the inorganic C pumped into the intracellular pool being lost as CO2 efflux with decreasing incident photosynthetically active radiation, and that algae relying on diffusive CO2 entry from the medium to Rubisco would be more common in low-irradiance habitats (review by Raven et al. 2000). The limited data available agree with these predictions (Raven et al., 2000, 2002; Burkhardt et al., 2001; de Araujo et al., 2011; Cornwall et al., 2015; see Table 3). Turning to temperature, Raven and Beardall (2014) show that algal CCMs occur at lower temperatures than does terrestrial C4 photosynthesis. Kranz et al. (2015) showed that the energy cost of algal CCMs decreased at low temperatures; it is not known if this is the case for terrestrial C4 photosynthesis.

Leakage from the photorespiratory carbon oxidation cycle(s)

Tcherkez (2013) gives an excellent critique of the CO2 fluxes associated with C3 photosynthesis, photorespiration, and respiration. With a carboxylase:oxygenase ratio of Rubisco in vivo in a C3 plant in the present atmosphere of 3:1, CO2 production in the photorespiratory carbon oxidation cycle is 0.167 of gross CO2 assimilation in photosynthesis (Raven, 1972a,b; Tcherkez, 2013). There is about 15% recycling of the photorespiratory CO2 and ‘dark’ respiratory CO2 production in photosynthesizing structures (Raven, 1972a,b; Tcherkez, 2013), so the CO2 release into the environment as a fraction of gross photosynthesis is 0.167×0.85 or 0.14; it is likely that an upper limit is 0.20. This is at the low end of the range for leakage in C4 plants and in algae CCMs (Table 3).

The various C3–C4 intermediate flowering plants have photosynthetic gas exchanges that show varying mixtures of C3 and C4 characteristics (Hylton et al., 1988; Rawsthorne et al., 1988a,b; von Caemmerer, 1989; Rawsthorne and Hylton, 1991; Morgan et al., 1993). This work shows the expression of most or all the glycine decarboxylase activity, and some of the Rubisco carboxylase–oxygenase, in bundle sheath cells. This location of the decarboxylase of the photorespiratory carbon oxidation cycle, with some Rubisco, in tightly packed bundle sheath cells increases recycling of CO2 from glycine decarboxylase by the carboxylase activity of Rubisco relative to leakage of CO2 back to the intercellular spaces.

CCMs increase the steady-state CO2:O2 ratios at the site of Rubisco activity; this decreases the ratio of Rubisco oxygenase activity to that of Rubisco carboxylase activity. The decreased rate of production of phosphoglycolate involves a decreased rate of the pathway(s) converting phosphoglycolate into phosphoglycerate and triose phosphate that can be used in core metabolism and/or complete oxidation to CO2 (Eisenhut et al., 2008; Hagemann et al., 2010; Young et al., 2011; Raven et al., 2012). Even this low flux is essential, since deletion of all three of the pathways of phosphoglycolate metabolism (photorespiratory carbon oxidation cycle; tartronic semialdehyde pathway; complete oxidation via oxalate) is lethal (Eisenhut et al., 2008; Hagemann et al., 2010; Raven et al., 2012). Comparable work has not been yet been carried out in photosynthetic eukaryotes with CCMs where, at least in embryophytes, the pathway of phosphoglycolate metabolism is the photorespiratory carbon oxidation cycle. However, it is known that the C4 and CAM CCMs decrease the rate of phosphoglycolate synthesis and flux through the photorespiratory carbon oxidation cycle relative to what occurs in otherwise comparable C3 plants.

Conclusions

Quantifying the flux of CO2 into and out of cells is difficult. All known irreversible decarboxylases produce CO2; CO2 is also the product/substrate of enzymes that can act as carboxylases and decarboxylases. Whether reversible of irreversible, decarboxylases produce CO2, which can potentially leak out of cells. Some irreversible carboxylases also have CO2 as their substrate; others use HCO3 –.

There is still controversy as to the relative role of permeation through the lipid bilayer and of movement through membrane proteins such as CO2-selective aquaporins in the downhill, non-energized, movement of CO2. Such movement is involved in CO2 entry in terrestrial and aquatic organisms with C3 physiology and biochemistry, as well as terrestrial C4 plants and all CAM plants. Although there is also some evidence of active CO2 transport at the plasmalemma of algae, downhill CO2 transport is part of some mechanisms involved in the use of external HCO3 – and CCM function. Further work is needed to test the validity of the mechanism based on localized surface acidification in marine macrophytes, and on HCO3 – conversion to CO2 in the thylakoid lumen.

HCO3 – active influx at the plasmalemma underlies all cyanobacterial and some algal CCMs. HCO3 – can also enter chloroplasts of some algae, possible as part of a CCM. Leakage from the intracellular CO2 and HCO3 – pool of CCMs sometimes occurs as HCO3 –, but typically occurs as CO2. Leakage from cyanobacterial and microalgal CCMs, and terrestrial C4 plants and hornworts with CCMs, usually involve half or less of the gross inorganic C entering in the CCM, but can be as high as 80%. CO2 leakage to the environment from photorespiration in C3 plants is less than 20% of gross photosynthesis. Leakage from terrestrial CAM plants, algal macrophytes, and vascular aquatic macrophytes with CCMs (C4, CAM, biophysical CCMs) has been less extensively examined. From what is known, CO2 leakage can be appreciable in many photoautotrophs with CCMs and increases the energetic cost of net inorganic carbon fixation (see Raven et al., 2014).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Table S1. Leakage of inorganic C from CCMs as a fraction of the inorganic C pumped into the intracellular pool.

Acknowledgements

Comments from two anonymous referees have been very valuable. Discussions with Murray Badger, Joseph Berry, Graham Farquhar, Mario Giordano, Howard Griffiths, Andrew Johnston, Aaron Kaplan, Jon Keeley, Janet Kübler, Jeffrey MacFarlane, Stephen Maberly, Barry Osmond, F. Andrew Smith, and J. Andrew C. Smith have been very helpful. The University of Dundee is a registered Scottish charity, No 015096.

References

- Amoroso G, Sültemeyer D, Thyssen C, Fock HP. 1998. Uptake of HCO3 - and CO2 in cells and chloroplasts from the microalgae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Dunaliella tertiolecta . Plant Physiology 116, 193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Bassett M, Comins HN. 1985. A model for HCO3 - accumulation and photosynthesis in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. Plant Physiology 77, 465–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Palmqvist K, Yu JW. 1994. Measurements of CO2 and HCO3 - fluxes in cyanobacteria and microalgae during steady-state photosynthesis. Physiologia Plantarum 90, 529–536. [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD. 2003. CO2 concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria: molecular components, their diversity and evolution. Journal of Experimental Botany 54, 609–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardall J. 1981. CO2 accumulation by Chlorella saccharophila (Chlorophyceae) at low external pH: evidence for active transport of inorganic carbon at the chloroplast envelope. Journal of Phycology 17, 371–373. [Google Scholar]

- Bellasio C, Griffiths H. 2014. Acclimation of low light by C4 maize: implications for bundle sheath leakiness. Plant Cell and Environment 37, 1046–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boron WF, Endeward V, Gros G, Musa-Aziz R, Pohl P. 2011. Intrinsic CO2 permeability of cell membranes and potential biological relevance of CO2 channels. ChemPhysChem 12, 1017–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs GE. 1959. Bicarbonate ions as a source of carbon dioxide for photosynthesis. Journal of Experimental Botany 10, 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt S, Amoroso G, Riebesell U, Sültemeyer D. 2001. CO2 and HCO3 - uptake in marine diatoms acclimated to different CO2 concentrations. Limnology and Oceanography 46, 1378–1391. [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn W, Ting IP, Sternberg LO. 1979. Relationship between stomatal behaviour and internal carbon dioxide concentrations in Crassulacean Metabolism plants. Plant Physiology 63, 1029–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn W, Goh CJ, Avadhani PN. 1985. Photosynthetic carbon assimilation in a shootless orchid, Chiloschista usenoides (DON) LDL. A variant on crassulacean acid metabolism. Plant Physiology 77, 83–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman B, Espie GA. 1985. CO2 uptake and transport in leaf mesophyll cells. Plant Cell and Environment 8, 449–457. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall CE, Revill AT, Hurd CL. 2015. High prevalence of diffusive uptake by CO2 by macroalgae in a temperate subtidal system. Photosynthesis Research 124, 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo ED, Patel J, de Araujo C, Rogers SP, Short SM, Cambell DA, Espie GS. 2011. Physiological characterization and light response of the CO2-concentrating mechanism in the filamentous cyanobacterium Leptolyngbya sp. CPPP 696. Photosynthesis Research 109, 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveau JST, Khosravari H, Lew RR, Colman B. 1998. CO2 uptake mechanism in Eremosphaera viridis . Canadian Journal of Botany 76, 1161–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Deveau JST, Lew RR, Colman B. 2001. Evidence for active CO2 uptake by a CO2-ATPase in the acidophilic green alga Eremosphaera viridis . Canadian Journal of Botany 79, 1274–1281. [Google Scholar]

- Eichner M, Thoms S, Kranz SA, Rost B. 2015. Cellular inorganic carbon fluxes in Trichodesmium: a combined approach using measurements and modelling. Journal of Experimental Botany 66, 749–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhut M, Ruth W, Halmovich M, Bauwe H, Kaplan A, Hagemann M. 2008. The photorespiratory glycolate metabolism is essential for cyanobacteria and might have been transferred endosymbiotically to plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA 105, 17199–17204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endeward V, Al-Samir S, Itel F, Gros G. 2014. How does carbon dioxide permeate cell membranes? A discussion of concepts, results and methods. Frontiers in Physiology 4, Article 382, pp.1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espie GS, Colman B. 1986. Inorganic carbon uptake during photosynthesis. I. A theoretical analysis using the isotope disequilibrium technique. Plant Physiology 80, 863–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espie GS, Owttrim GW, Colman B. 1986. Inorganic carbon uptake during photosynthesis. II. Uptake by isolated Asparagus mesophyll cells during isotope disequilibrium. Plant Physiology 80, 870–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, Kaldenhoff R, Genty B, Terashima I. 2009. Resistances along the CO2 diffusion pathway inside leaves. Journal of Experimental Botany 60, 2235–2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field CB, Behrenfeld J, Randerson PG, Falkowski PG. 1998. Primary production in the biosphere: integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science 29, 737–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestyne SM, Wu W, Youn H, Davison VJ. 2009. Interrogating the mechanism of a tight-binding inhibitor of AIR carboxylase. Bioinorganic and Medicinal Chemistry 17, 794–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furbank RT, Jenkins CLD, Hatch MD. 1989. CO2 concentrating mechanism of C4 photosynthesis: permeability of isolated bundle sheath cells to inorganic carbon. Plant Physiology 91, 1364–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano M, Beardall J, Raven JA. 2005. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in algae: mechanisms, environmental modulation, and evolution. Annual Review of Plant Biology 6, 99–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TGA, Snelgar WP. 1982. A comparison of photosynthesis in two thalloid liverworts. Oecologia 54, 275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutknecht J, Bisson MA, Tosteson DC. 1977. Diffusion of carbon dioxide through lipid bilayer membranes. Effects of carbonic anhydrase, bicarbonate and unstirred layers Journal of General Physiology 69, 779–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann M, Eisenhut M, Hackenberg C, Bauwe H. 2010. Pathway and importance of photorespiratory 2-phosphoglycolate metabolism in cyanobacteria. Advances in Experimental Biology and Medicine 675, 91–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanba YT, Shibasaka M, Hayashi Y, Hayakawa T, Kasamo K, Terashima I, Katsuhara M. 2004. Overexpression of the barley aquaporin HvPIP2;1 increases internal CO2 conductance and CO2 assimilation in the leaves of transgenic rice plants. Plant and Cell Physiology 45, 521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häusler RE, Holtum JAM, Latzko E. 1987. CO2 is the inorganic carbon substrate of NADP+ malic enzymes from Zea mays and from wheat germ. European Journal of Biochemistry 163, 619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckwolf M, Pater D, Hanson DT, Kaldenhoff R. 2011. The Arabidopsis thaliana aquaporin AtPIP1;2 is a physiologically relevant CO2 transport facilitator. The Plant Journal 67, 795–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson BM. 2014. A chloroplast pump model for the CO2 concentrating mechanism in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum , Photosynthesis Research 121, 223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson BM, Dupont CL, Allen AE, Morel FMM. 2011. Efficiency of the CO2-concentrating mechanism of diatoms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 108, 3830–3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson BM, Young JN, Tansik AL, Binder BJ. 2014. The minimal CO2 concentrating mechanism of Prochlorococcus MED4 is effective and efficient. Plant Physiology 166, 2205–2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huertas IE, Lubián LM. 1997. Comparative study of dissolved inorganic carbon and photosynthetic responses in Nannochloris (Chlorophyceae) and Nannochloropsis (Eustigmatophyceae) species. Canadian Journal of Botany 76, 1104–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Huertas IE, Colman B, Espie GS, Lubián LM. 2000a. Active transport of CO2 by three species of marine microalgae, Journal of Phycology 36, 314–320. [Google Scholar]

- Huertas IE, Espie GS, Colman B, Lubián LM. 2000b. Light-dependent bicarbonate uptake and CO2 efflux in the microalga Nannochloropsis gaditana . Plants 211, 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huertas IE, Lubián LM, Espie GS. 2002. Mitochondrial-driven bicarbonate transport supports photosynthesis in a marine microalga. Plant Physiology 130, 284–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hylton CM, Rawsthorne S, Smith AM, Jones DA, Woolhouse HW. 1988. Glycine decarboxylase is confined to the bundle-sheath cells of leaves of C3-C4 intermediate species of Moricandia . Planta 175, 452–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itel F, Al-Samir S, Öberg F, et al. 2012. CO2 permeability of cell membranes is regulated by membrane cholesterol and protein gas channels. The FASEB Journal 26, 5182–5191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins CLD, Burnell JN, Hatch MD. 1987. Form of inorganic carbon involved as a product and as an inhibitor in C4 photosynthesis. Plant Physiology 85, 952–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungnick N, Ma Y, Mukherjee B, Cronan JC, Speed DJ, Laborde SM, Longstreth DJ, Moroney JV. 2014. The carbon concentrating mechanism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: finding the missing pieces. Photosynthesis Research 121, 159–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai L, Kaldendorf R. 2014. A refined model of water and CO2 membrane diffusion: Effects and contribution of sterols and proteins. Scientific Reports 4, 6665. doi: 10.1028/srep06665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JL, Edwards GE, Cousins A. 2012. The efficiency of the CO2-concentrating mechanism during single-cell C4 photosynthesis. Plant Cell and Environment 33, 1935–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klavsen SK, Maberly SC. 2010. The effect of light and CO2 on inorganic carbon uptake in the invasive aquatic CAM-plant Crassula helmsii . Functional Plant Biology 37, 727–747. [Google Scholar]

- Korb RE, Saville PJ., Johnston AM, Raven JA. 1997. Sources of inorganic carbon for photosynthesis by three species of marine diatoms. Journal of Phycology 33, 433–440. [Google Scholar]

- Kranz SA, Sültemeyer D, Richter K-U, Rost B. 2009. Carbon acquisition in Trichodesmium: the effect of pCO2 and diurnal changes. Limnology and Oceanography 54, 548–559. [Google Scholar]

- Kranz SA, Levitan O, Richter K-U, Prasil O, Berman-Frank I, Rost B. 2010. Combined effects of CO2 and light on the N2 fixing cyanobacterium Trichodesmium IMS101: physiological responses. Plant Physiology 154, 334–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz S, Young JN, Goldman J, Tortell PD, Bender M, Morel FMM. 2015. Low temperature reduces the energetic requirement for the CO2 concentrating mechanism in diatoms. New Phytologist 205, 192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kromdijk J, Ubierna N, Cousins AB, Griffiths H. 2014. Bundle-sheath leakiness in C4 photosynthesis: a careful balancing act between CO2 concentration and assimilation. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 3443–3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kübler JE, Johnston AM, Raven JA. 1999. The effects of reduced and elevated CO2 and O2 on the seaweed, Lomentaria articulata . Plant, Cell and Environment 22, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar]

- Maberly SC. 2014. The fitness of the environments of air and water for photosynthesis, growth, reproduction and dispersal of photoautotrophs: an evolutionary and biogeochemical perspective. Aquatic Botany 118, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Maberly SC, Madsen TV. 2002. Freshwater angiosperm carbon concentrating mechanisms: processes and patterns. Functional Plant Biology 29, 393–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maberly SC, Ball LA, Raven JA, Sültemeyer D. 2009. Inorganic carbon acquisition by chrysophytes. Journal of Phycology 45, 1052–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacFarlane JJ, Raven JA. 1985. External and internal CO2 transport in Lemanea: interactions with the kinetics of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase. Journal of Experimental Botany 36, 610–622. [Google Scholar]

- MacFarlane JJ, Raven JA. 1989. Quantitative determination of the unstirred layer permeability and kinetic parameters of RUBISCO in Lemanea mamillosa . Journal of Experimental Botany 40, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- MacFarlane JJ, Raven JA. 1990. C, N and P nutrition of Lemanea mamillosa Kutz. (Batrachospermales, Rhodophyta) in the Dighty Burn, Angus, Scotland. Plant, Cell and Environment 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S-I, Badger MR, Price GD. 2002. Novel gene products associated with NdhD3/D4-containing NDH1 complexes are involved in photosynthetic CO2 hydration in the cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. Molecular Microbiology 43, 425–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan NM, Brenner MP. 2014. Systems analysis of the CO2 concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria. eLife 3, e2043. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02043. see also Correction published 29 April 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinn PJ, Coleman JR, Canvin DT. 1997. Influx and efflux of inorganic carbon during steady-state photosynthesis of air-grown Anabaena variabilis . Canadian Journal of Botany 75, 1913–1926. [Google Scholar]

- Menon BB, Heihorst S, Shively JM, Canon GC. 2010. The carboxysome shell is permeable to protons. Journal of Bacteriology 192, 5881–5886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer M, Seibt U, Griffiths H. 2008. To concentrate or ventilate. Carbon acquisition, isotope discrimination and physiological ecology of early land plant life forms. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 363, 2767–2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missner A, Kügler P, Saparov SM, Sommer K, Mathai JC, Zeidel ML. 2008. Carbon dioxide transport through membranes. Journal of Biological Chemistry 282, 25340–25347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CL, Turner SR, Rawsthorne S. 1993. Coordination of the cell-specific of the four subunits of glycine decarboxylase and of serine hydroxymethyltrasnferase in leaves of C3-C4 intermediate species from different genera. Planta 190, 468–473. [Google Scholar]

- Moroney JV, Ynalvez RA. 2007. Proposed carbon dioxide concentrating mechanism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii . Eukaryotic Cell 6, 1251–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz J, Merrett MJ. 1989. Inorganic-carbon transport in some marine eukaryotic microalgae. Planta 178, 450–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K, Tanaka A, Matsuda Y. 2013. SLC4 family transporters in a marine diatom directly pump bicarbonate from seawater. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 110, 1767–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EA, Sage TL, Sage RF. 2005. Functional leaf anatomy of plants with crassulacean acid metabolism. Functional Plant Biology 32, 409–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EA, Sage RF. 2008. Functional constraints of CAM leaf anatomy: tight cell packing is associated with increased CAM function across a gradient of CAM expression. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 1841–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JR, Raven JA. 1995. Photosynthetic carbon assimilation by Crassula helmsii . Oecologia 101, 494–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü, Wright IJ, Evans JR. 2009. Leaf mesophyll conductance in 35 Australian sclerophylls covering a broad range of foliage structure and physiological variation. Journal of Experimental Botany 60, 2433–2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobel PS. 2005. Physicochemical and environmental plant physiology. 3rd ed Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Badger MR. 1985. Inhibition by proton buffers of photosynthetic utilization of bicarbonate in Chara corallina . Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 12, 257–267. [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Badger MR, Bassett ME, Whitecross MI. 1985. Involvement of plasmalemmasomes and carbonic anhydrase in photosynthetic utilization of bicarbonate in Chara corallina . Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 12, 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Maeda S-I, Omata T, Badger MR. 2002. Modes of active inorganic carbon uptake in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC7942. Functional Plant Biology 29, 131–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA. 1970. Exogenous inorganic carbon sources in plant photosynthesis. Biology Reviews 45, 167–221. [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA. 1972a. Endogenous inorganic carbon sources in plant photosynthesis. I. Occurrence of the dark respiratory pathways in illuminated green cells. New Phytologist 71, 227–247. [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA. 1972b. Endogenous inorganic carbon sources in plant photosynthesis. II. Comparison of total CO2 production in the light with measured CO2 evolution in the light. New Phytologist 71, 995–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA. 1984. Energetics and Transport on Aquatic Plants. A R Liss, New York, NY: pp. ix + 587. [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA. 1997a. Inorganic acquisition by marine autotrophs. Advances in Botanical Research 27, 85–209. [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA. 1997b. CO2 concentrating mechanisms: a direct role for thylakoid lumen acidification? Plant, Cell and Environment, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA. 2006. Sensing inorganic carbon: CO2 and HCO3 - . Biochemical Journal 396, e5–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA, Glidewell SM. 1981. Processes limiting photosynthetic conductance. In: Physiological Processes Limiting Plant Productivity (ed. by C.B., Johnson), 109–136. Butterworths, London. [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA, Kübler JE, Beardall J. 2000. Put out the light, and then put out the light. Journal of the Marine Biological Association UK 80, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA, Johnston AM, Kübler JE, et al. 2002. Mechanistic interpretation of carbon isotope discrimination by marine macroalgae and seagrasses. Functional Plant Biology 29, 355–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA, Ball LA, Beardall J, Giordano M, Maberly SC. 2005. Algae lacking carbon concentrating mechanisms. Canadian Journal of Botany 83, 879–890. [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA, Giordano M, Beardall J, Maberly SC. 2012. Algal evolution in relation to atmospheric CO2: carboxylases, carbon-concentrating mechanisms and carbon oxidation cycles. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 367, 493–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA, Hurd CJ. 2012. Ecophysiology of photosynthesis in macroalgae. Photosynthesis Research 113, 105–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA, Beardall J. 2014. CO2 concentrating mechanisms and environmental change. Aquatic Botany 118, 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA, Beardall J, Giordano M. 2014. Energy costs of carbon dioxide concentrating mechanisms in aquatic organisms. Photosynthesis Research 121, 111–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawsthorne S, Hylton CM, Smith AM, Woolhouse HW. 1988a. Photorespiratory metabolism and immunogold localization of photorespiratory enzymes in C3 and C3-C4 intermediate species of Moricandia . Planta 173, 298–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawsthorne S, Hylton CM, Smith AM, Woolhouse HW. 1988b. Photorespiratory metabolism and immunogold localization of photorespiratory enzymes in C3 and C3-C4 intermediate species of Moricandia . Planta 176, 527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawsthorne S, Hylton CM. 1991. The relationship between the post-illumination CO2 burst and glycine metabolism in leaves of C3 and C3-C4 intermediate species of Moricandia . Planta 186, 122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhold L, Zviman M, Kaplan A. 1987. Inorganic carbon fluxes in cyanobacteria: a quantitative model. In: J, Biggins, ed. Progress in Photosynthesis. Martinus Nijhof, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp. 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhold L, Kosloff R, Kaplan A. 1991. A model for inorganic carbon fluxes and cyanobacterial carboxysomes. Canadian Journal of Botany 69, 984–988. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie RJ, Nadolny C, Larkum AWD. 1996. Driving forces for bicarbonate transport in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus R-2 (PCC 7942). Plant Physiology 112, 1573–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost B, Riebesell U, Sültemeyer D. 2006a. Carbon acquisition of marine phytoplankton. Effect of photoperiod length. Limnology and Oceanography 51, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rost B, Richter K-U, Riebesell U, Hansen PJ. 2006b. Inorganic carbon acquisition by red tide dinoflagellates. Plant Cell and Environment 29, 810–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost B, Kranz SA, Richter K-U, Tortell PD. 2007. Isotope disequilibrium and mass spectrometric studies of inorganic carbon acquisition by phytoplankton. Limnology and Oceanography: Methods 5, 328–337. [Google Scholar]

- Rotatore C, Colman B. 1990. Uptake of inorganic carbon by isolated chloroplasts of Chlorella ellipsoidea . Plant Physiology 93, 1597–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotatore C, Colman B. 1991a. The localization of active inorganic carbon transport at the plasma membrane in Chlorella ellipsoidea . Canadian Journal of Botany 69, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Rotatore C, Colman B. 1991b. The active uptake of carbon dioxide by the unicellular green algae transport Chlorella saccharophila and C. ellipsoidea . Plant Cell and Environment 14, 371–375. [Google Scholar]

- Rotatore C, Colman B. 1991c. The acquisition and accumulation of inorganic carbon by the unicellular green algae transport Chlorella ellipsoidea . Plant Cell and Environment 14, 377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Rotatore C, Lew RR, Colman B. 1992. Active uptake of CO2 during photosynthesis in the green alga Eremosphaera viridis is mediated by a CO2-ATPase. Planta 188, 539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salon C, Mir NA, Canvin DT. 1996a. Influx and efflux of inorganic carbon in Synechococcus UTEX 625. Plant Cell and Environment 19, 247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Salon C, Mir NA, Canvin DT. 1996b. HCO3 - and CO2 leakage from and Synechococcus UTEX 625. Plant Cell and Environment 19, 260–274. [Google Scholar]

- Salon C, Canvin DT. 1997. HCO3 - efflux and the regulation of intracellular Ci pool size in Synechococcus UTEX 625. Canadian Journal of Botany 75, 290–300. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD, Berry JA. 1985. Carbon isotope fractionation of algae influenced by an inducible CO2-concentrating mechanism. In: Lucas WJ, Berry JA, eds. Inorganic carbon uptake by aquatic photosynthetic organisms. Rockville: American Society of Plant Physiologists, 389–401. [Google Scholar]

- Sherlock DJ, Raven JA. 2001. Interactions between carbon dioxide and oxygen in the photosynthesis of three species of marine red algae. Botanical Journal of Scotland 53, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Still CJ, Berry JA. 2003. Global distribution of C3 and C4 vegetation: carbon cycle Implications. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 17, 1006, pp. 6-1– 6–13. doi: 10.1029/2001GB001807 [Google Scholar]

- Sültemeyer D, Rinast K-A. 1996. The CO2 permeability of the plasma membrane of Chlamydomonas reinhartii: mass spectrometric 18O-exchange measurements from 13C18O2 in suspensions of carbonic anhydrase-loaded plasma-membrane vesicles. Planta 200, 358–368. [Google Scholar]

- Tazoe Y, von Caemmerer S, Badger MR, Evans JR. 2009. Light and CO2 do not affect the mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion in wheat leaves. Journal of Experimental Botany 60, 2291–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazoe Y, von Cammerer S, Estavillo GM, Evans JR. 2011. Using tunable diode laser spectroscopy to measure carbon isotope discrimination and mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion dynamically at different CO2 concentrations. Plant Cell and Environment 34, 580–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez G. 2013. Is the recovery of (photo)respiratory CO2 and intermediates minimal? New Phytologist 198, 334–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchernov D, Hassidim N, Luz B, Sukenik A, Reinhold L, Kaplan A. 1997. Sustained net CO2 evolution during photosynthesis by marine microorganisms. Current Biology 7, 725–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchernov D, Hassidim N, Vardi A, Luz B, Sukenik A, Reinhold L, Kaplan A. 1998. Photosynthesizing marine organism can constitute a source of CO2 rather than a sink. Canadian Journal of Botany 76, 949–953. [Google Scholar]

- Tchernov D, Silverman J, Luz B, Reinhold L, Kaplan A. 2003. Massive light-dependent cycling of inorganic carbon between oxygenic between oxygenic photosynthetic microorganism and their surroundings. Photosynthesis Research 77, 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortell PD, Reinfelder JR, Morel FMM. 1997. Active uptake of bicarbonate by diatoms. Nature 390, 243–244.9384376 [Google Scholar]

- Tortell PD, Payne C, Guegen C, Strzepek RF, Boyd PW, Rost B. 2008. Inorganic carbon uptake by Southern Ocean phytoplankton. Limnology and Oceanography 53, 1266–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchihira A, Hanba YT, Kato N, Doi T, Kawazu T, Maeshima M. 2010. Effect of overexpression of radish plasma membrane aquaporins on water-use efficiency, photosynthesis and growth of Eucalyptus trees. Tree Physiology 30, 417–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehlein N, Lovisolo C, Siefritz F, Kaldenhoff R. 2003. The tobacco aquaporin NtAQP1 is a membrane CO2 pore with physiological functions. Nature 425, 734–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehlein N, Otto B, Hanson DT, Fischer M, McDowell N, Kaldenhoff R. 2008. Function of Nicotiana tabacum aquaporins as chloroplast gas pores challenges the concept of membrane CO2 permeability. The Plant Cell 20, 648–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hunnik E, Amoroso G, Sültemeyer D. 2002. Uptake of CO2 and bicarbonate by intact cells and chloroplasts of Tetraedron minimum and Chlamydomonas noctigama . Planta 215, 763–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Caemmerer S. 1989. A model of photosynthesising CO2 assimilation and carbon-isotope discrimination in leaves of certain C3-C4 intermediates. Planta 178, 463–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Caemmerer S, Ghanoum O, Pengelly JJL, Cousins AB. 2014. Carbon isotope discrimination as a tool to explore C4 photosynthesis. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 3459–3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker NA, Smith FA, Cathers IR. 1980. Bicarbonate assimilation by freshwater charophytes and higher plants. I. Membrane transport of bicarbonate is not proven. Journal of Membrane Biology 12, 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Spalding MJ. 2014. Acclimation to very low CO2: contribution of limiting CO2 inducible proteins, LCIb and LCIA, to inorganic carbon uptake in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii . Plant Physiology 166, 2040–2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren CR. 2008. Stand aside stomata, another actor deserves centre stage: the forgotten role of the internal conductance to CO2 transfer. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 1475–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter K, Smith JAC, eds 1996. Crassulacean Acid Metabolism: Biochemistry, Ecophysiology and Evolution. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Winter K, Holtum JAM, Smith JAC. 2015. Crassulacean acid metabolism: a continuous or discrete trait? New Phytologist 208, 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T, Sato E, Iguchi H, Fukuda Y, Fukuzawa H. 2015. Characterization of cooperative bicarbonate uptake into chloroplast stroma in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii . Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA 112, 7315–7320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JD, Shastri A, Stephanopoulos G, Morgan JA. 2011. Mapping photoautotrophic metabolism with isotopically nonstationary 13C flux analysis. Metabolic Engineering 13, 656–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.