Abstract

Background

Acute pancreatitis is a common disease with wide clinical variation and its incidence is increasing. Acute pancreatitis may vary in severity, from mild self-limiting pancreatic inflammation to pancreatic necrosis with life-threatening sequelae. Severity of acute pancreatitis is linked to the presence of systemic organ dysfunctions and/or necrotizing pancreatitis.

Aim and objectives

The present study was aimed to assess the clinical profile of acute pancreatitis and to assess the efficacy of various severity indices in predicting the outcome of patients.

Methodology

This was a prospective study done in Sri Ramachandra Medical College and Hospital from April 2012–September 2014. All patients with a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis were included in this study. Along with routine lab parameters, serum amylase, lipase, lipid profile, calcium, CRP, LDH, CT abdomen, CXR and 2D Echo was done for all patients.

Results

A total of 110 patients were analysed. 50 patients required Intensive care, among them 9 patients (18%) died. 20 patients (18.2%) had MODS, 15 patients (13.6%) had pleural effusion, 9 patients (8.2%) had pseudocyst, 2 patients(1.8%) had hypotension, 2 patients(1.8%) had ARDS and 2 patients(1.8%) had DKA. In relation to various severity indices, high score of CRP, LDH and CT severity index was associated with increased morbidity and mortality. 15 patients (13.6%) underwent open necrosectomy surgery, 3 patients (2.7%) underwent laparoscopic necrosectomy and 7 patients (6.4%) were tried step up approach but could not avoid surgery. Step up approach and surgery did not have a significant reduction in the mortality.

Conclusion

Initial assessment of severity by CRP, LDH and lipase could be reliable indicators of outcome in acute pancreatitis

Keywords: Acute pancreatitis, C-Reactive Protein, LDH, Severity index, Step up approach

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis is a common disease with wide clinical variation and its incidence is increasing. The average mortality rate in severe acute pancreatitis approaches 2–10 %.[1] Severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) develops in about 25% of patients with acute pancreatitis. Severe acute pancreatitis is a two phase systemic disease. The first phase is characterised by extensive pancreatic inflammation and/or necrosis and is followed by a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) that may lead to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) with in the first week. About 50% of deaths occur within the first week of the attack, mostly from MODS. The formation of infected pancreatic necrosis or fluid collection occurs usually in the second week. The factors which cause death in most patients with acute pancreatitis seem to be related specifically to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and these deaths account for 40–60% of in-hospital deaths in all age groups. The mortality figures associated with MODS vary between 30–100 %. Infection is not a feature of the early phase. Pro inflammatory cytokines contribute to respiratory, renal, and hepatic failure. The “second or late phase” which starts 14 days after the onset of the disease, is marked by infection of the gland, necrosis and systemic complications causing a significant increase in mortality. The association between increasing age and death from acute pancreatitis is well documented. Respiratory failure is the most common type of organ failure in acute pancreatitis. [2]

According to the severity, acute pancreatitis is divided into mild acute pancreatitis (absence of organ failure and local or systemic complications, moderately severe acute pancreatitis (no organ failure or transient organ failure less than 48 hours with or without local complications) and severe acute pancreatitis (persistent organ failure more than 48 hours that may involve one or multiple organs). [3]

Initial evaluation of severity should include assessment of fluid loss, organ failure (particularly cardiovascular, respiratory, or renal compromise), measurement of the APACHE II score and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) score. [4, 5] Although measurement of amylase and lipase is useful for diagnosis of pancreatitis, serial measurements in patients with acute pancreatitis are not useful to predict disease severity, prognosis, or for altering management.

Routine abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan is not recommended at initial presentation because there is no evidence that CT improves clinical outcomes and the complete extent of pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis may only become clear 72 hours after the onset of acute pancreatitis.[6] Several other scoring systems also exist to predict the severity of acute pancreatitis based upon clinical, laboratory, radiologic risk factors, and serum markers but can be used only 24 to 48 hours after disease onset and have not been shown to be consistently superior to assessment of SIRS or the APACHE II score.

Several classification systems have been presented to assess the severity of acute pancreatitis. Presence of SIRS (Systemic inflammatory response syndrome), scores such as the Ranson, the Glasgow, and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) are practical for assessing the severity of the disease but are not sufficiently well validated for predicting mortality. Early organ dysfunction predicts disease severity and patients require early intensive care treatment. Antibiotic prophylaxis is usually ineffective and early enteral feeding results in reduction of local and systemic infection. [6, 7] Management of acute pancreatitis has changed significantly over the past years. Early management is nonsurgical, solely supportive and patients with infected necrosis with worsening sepsis need intervention. Early intensive care has definitely improved the outcome of patients. [8] Genetic polymorphisms and mutations also contribute to difficulty in predicting the outcome. [9]

The rising costs of ICU treatment and the need to prolong the life of critically ill patients creates a need for early identification of those patients who will benefit from intensive care. The present study was aimed at evaluating the mortality and morbidity risk in relation to various severity indices and the role of procedural intervention.

Material and methods

This was a prospective study done in Sri Ramachandra Medical College and Hospital, Chennai, India, from April 2012–September 2014. All patients with a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis were included in this study (110 consecutive patients). Patients with chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic malignancy were excluded from the study. Patients were classified into mild, moderate and severe acute pancreatitis based on Ranson’s score, Glasgow scoring and CT severity index (CTSI). Complete hemogram, liver function tests, renal function tests, serum amylase, serum lipase, random blood sugar, lipid profile, serum calcium and C-Reactive protein were done for all the patients. CECT abdomen was done when indicated and CT severity index was calculated. Patients with moderate and severe pancreatitis were managed in Intensive Care Unit. Patients with mild pancreatitis were managed in the ward. Step up approach and surgery was done in patients who did not improve on intensive medical management.

Hospital ethics committee approval and informed and written consent by the patient were obtained before undertaking the study. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 17 was used for the statistical analysis. A p-value of less than 0.05 was taken as being statistically significant.

Results

In the present study, most patients were in the age group of 21 to 40 years. We found that acute pancreatitis was found five times more common in males than in females. The results of the study with regard to various clinical and lab parameters are summarised in tables 2–3. Tables 4–6 summaries the correlation between various severity indices.

Table 2.

Clinical profile and outcome

| Parameter (N) | Discharge | Death | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Mellitus (14) | 13 | 1 | 0.97 |

| Hypentension (10) | 9 | 1 | 0.97 |

| CKD (2) | 2 | 0 | 0.97 |

| Alcoholics | 50 | 6 | 0.97 |

| Gall stones | 37 | 1 | 0.97 |

| Intensive care (50) | 41 | 9 | 0.01 |

| Hypotension (2) | 2 | 0 | 0.00 |

| MODS (20) | 12 | 8 | 0.00 |

| Pleural effusion (15) | 14 | 1 | 0.00 |

| ARDS (2) | 2 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Pseudocyst (9) | 9 | 0 | 0.00 |

| DKA (2) | 2 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Surgery (15) | 8 | 7 | 0.00 |

| Laparoscopy (3) | 3 | 0 | 0.00 |

Table 3.

Lab markers and Severity index

| Parameter | Final Outcome (N) Discharge/death |

Mean value Discharge/death |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amylase | 101/09 | 453.49/818.33 | 0.009 |

| Lipase | 101/09 | 538.02/956.56 | 0.000 |

| LDH | 97/09 | 494.27/666.67 | 0.003 |

| CRP | 72/06 | 2.135/2.967 | 0.001 |

| Ranson score | 97/09 | 3.95/6.56 | 0.001 |

| Glasgow score | 97/09 | 3.0/5.56 | 0.001 |

| CTSI / Balthazar | 97/08 | 5.44/8.25 | 0.003 |

Table 4.

Comparison of Ranson’s score with Glasgow and CTSI

| Ranson score | Glasgow score | CTSI | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Severe | 0–3 | 4–6 | 7–10 | ||

| 0–2 | 23 | 1 | 13 | 9 | 2 | 0.003 |

| 3–5 | 29 | 22 | 7 | 37 | 5 | |

| >5 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 3 | 27 | |

Table 5.

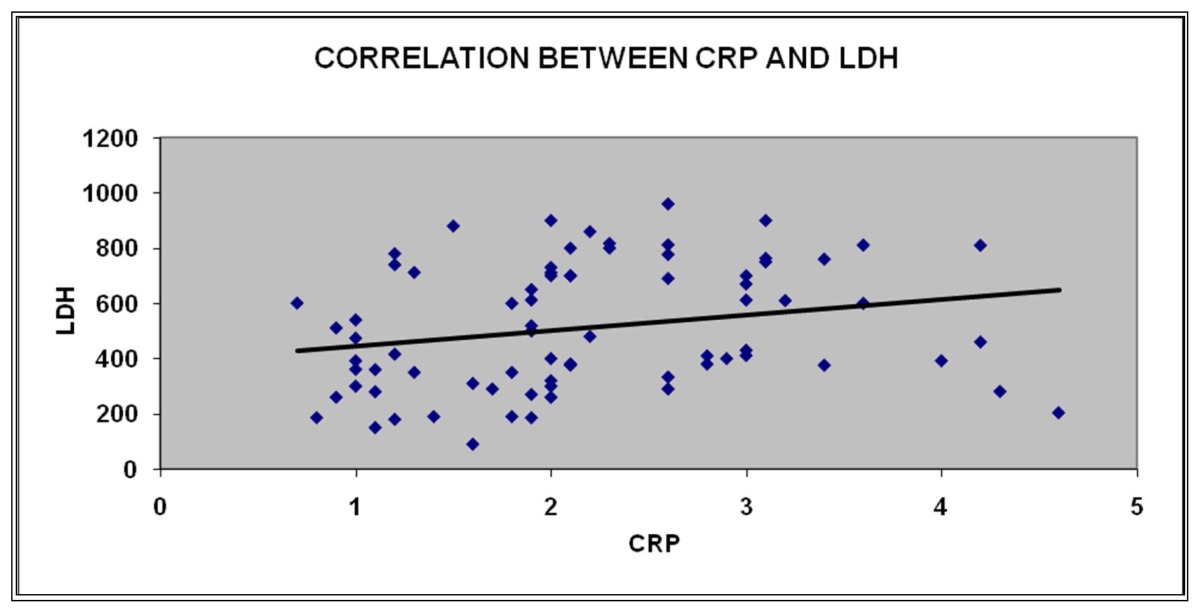

Correlation Between CRP and LDH

| CRP | LDH | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| CRP | Pearson Correlation | 1 | .229* |

| Sig. (2 tailed) | .045 | ||

| N | 78 | 77 | |

Table 6.

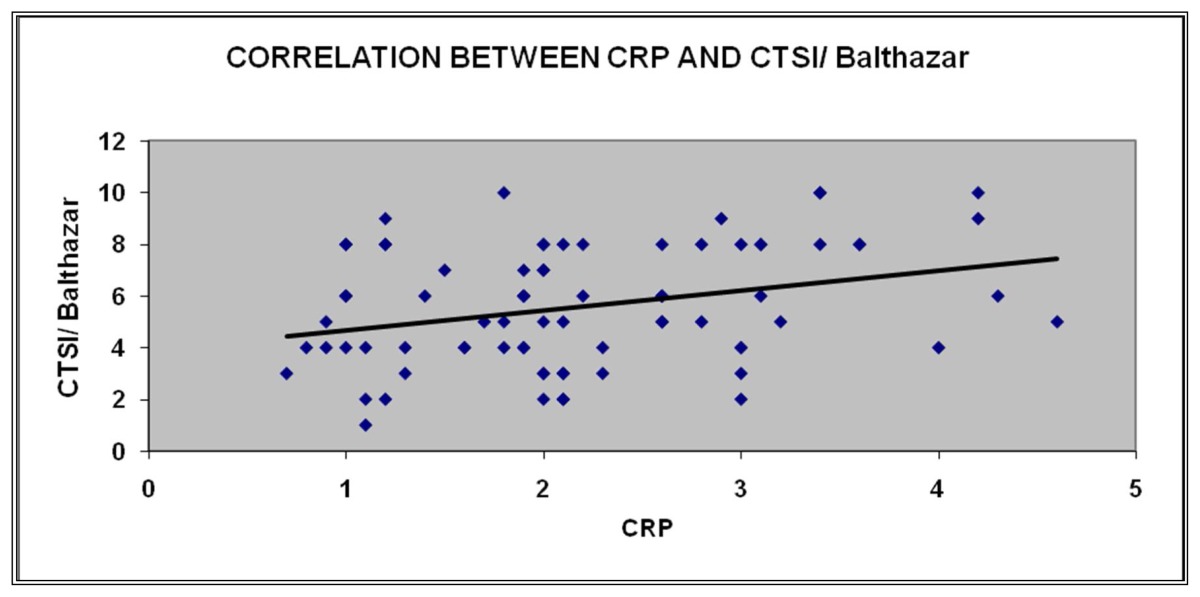

Correlation between CRP and CTSI / Balthazar

| CRP | CTSI/ Balthazar | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| CRP | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.309** |

| Sig. (2 tailed) | 0.66 | ||

| N | 78 | 78 | |

Among 20 patients with MODS, 8 patients died. Death was high in patients with MODS in spite of adequate measures. 2 patients had hypotension, were managed with IV fluids and inotropes, 2 patients developed ARDS, were managed with ventilator support but there was no death. There was no significant difference between alcohol induced pancreatitis and gall stone pancreatitis with regard to development of local, systemic complications and death.

The mean duration of hospital stay was 3.65 in mild pancreatitis (Ranson’s score < 3), 8.35 in patients with complications who recovered (Ranson’s score 3–5) and 10.55 in patients who died (Ranson’s score >5). Among the 50 patients who required intensive care the minimum duration of stay was 5 days and the maximum was 21 days. Admission values in patients who died had a high CRP value (1.6 minimum value and 4.3 maximum value), high LDH (minimum 350 IU and maximum 980 IU) and high lipase (minimum 667U/L and maximum 1100 U/L). Admission values of amylase (minimum 146 U/L and maximum 1200 U/L) and leucocyte count (minimum 4430/Cumm and maximum 18716/Cumm) did not correlate with mortality and morbidity.

Discussion

The severe necrotizing form of acute pancreatitis is a life threatening condition with high morbidity. Mortality may increase, especially if bacterial contamination of the pancreatic necrosis occurs. An improved outcome in the severe form of the disease is based on early identification of disease severity and subsequent focused management of these high-risk patients. Despite the availability of several clinical (Ranson’s criteria, APACHE II score, Glasgow scoring system) and radiological scoring systems (CTSI /Balthazar scoring system), accurate prediction of the best treatment strategies and outcome after acute necrotizing pancreatitis remains enigmatic. These scoring systems could be used as triaging tools for appropriate management.

In the present study we had the objective of analysing the various severity indices and whether a simple lab parameter could aid in the assessment of severity. The present severity indices are still significant in severity assessment. In developing countries (especially in a teaching hospital which is a resource limited setting) we wanted to find out whether initial measurement of serum amylase, lipase, CRP, LDH along with clinical parameters could be used as a simple tool for morbidity and mortality risk.

Out of 110 patients alcohol induced pancreatitis was higher (51%) than gall Stone induced pancreatitis. This can be explained by the greater incidence of alcohol abuse in India. Females were more predisposed to develop gall stones and gall stone induced pancreatitis than men. Scoring system in acute pancreatitis increases accuracy of prognosis, mortality and morbidity increases with increasing scores. Mean Amylase was 453 for discharged patients and 818 in patients who had death. Mean lipase was 538 for discharged patients and 956 in patients who died. Mean Ranson’s score was 3.95 in discharged patients and was 6.56 in patients who had death. Mean Glasgow score was 3 in discharged patients and 5.56 in patients who had death. Ranson’s score and Glasgow score can be used for triaging patients to intensive care and aggressive therapy. Studies done for comparison of various scores have found out that no single scoring index could accurately predict the outcome but they were useful in initial triaging of patients. [10, 11] The present study emphasises that Ranson’s score could be still useful in initial triage of patients and subsequent management.

Mean CTSI was 5.44 in discharged patients and 8.25 in patients who had death. There was a significant difference in the CT Severity Index of alcoholic pancreatitis in comparison to gall bladder pancreatitis where the score was higher for alcohol induced pancreatitis. A study by Bollen T et al suggested CT severity index correlated well with mortality and morbidity. [12]

Multivariate analysis revealed LDH and CRP on admission showed greatest independent significance in predicting outcome. In our study mean LDH was 494 in discharged patients and 666 in patients who had death. Mean CRP was 2.1 in discharged patients and 2.96 in patients who had death. It was with great interest we observed the significance of CRP and LDH in predicting the outcome. As per the available literature and studies high level of CRP at 48 hours is a significant predictor of morbidity and mortality. In the present study high CRP levels at admission was associated with high morbidity and mortality. LDH and CRP at admission may supplement clinical judgment in selecting high risk group.

Assessment of BUN (Blood urea nitrogen) and serum creatinine on admission had no significant prediction of morbidity and mortality but fluid replacement in the initial 24 hours was crucial for early recovery. In a study by Wu Bu et al BUN > 20 meq/dL on admission or any increase in BUN in the first 24 hours was associated with high risk of mortality. [13] Lankisch PG et al observed that normal creatinine on admission had a negative predictive value for severity. [14]

In recent years, treatment of acute severe pancreatitis has shifted away from early surgical treatment to aggressive intensive care management. Surgery in severe acute pancreatitis is a morbid procedure associated with complications in most of the patients. Surgery is also known to lead to long term pancreatic insufficiency. The high mortality encountered with surgery essentially reflects the hazard of operating on a critically ill, septic patients with multi organ failure. Delayed surgery is always a better option especially in patients with sterile necrosis and who show clinical improvement with intensive care. High morbidity and mortality is involved in operative necrosectomy, hence minimally invasive strategies are increasingly explored by gastrointestinal surgeons, radiologists and gastroenterologists. Percutaneous drainage (PCD), endoscopic transgastric procedures and minimally invasive procedures have all been proposed as alternatives to open necrosectomy. It has been reported that a reversal of sepsis along with a reversal in organ failure (26%) is seen in patients managed by step up approach using PCD alone or along with multiple drainage insertion and high volume lavage. [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]

In the present study 85 patients (77.3%) did not undergo any intervention, 15 patients (13.6%) underwent open necrosectomy surgery, 3 patients (2.7%) underwent laparoscopic necrosectomy and 7 patients (6.4%) were tried step up approach but could not avoid surgery. The patients who were enrolled for step up approach were monitored more closely for any deterioration in their clinical condition to decide about surgery. 7 out of 8 patients who underwent surgery died. Step up approach did not demonstrate significant advantage. This could be explained by the procedure related risks in a critically ill patient. Nevertheless procedure should not be a deterrent to patients who will benefit from surgery (infected necrosis with worsening sepsis) irrespective of the risks involved, if not done the patients still carry a higher risk for mortality.

Various other markers especially urinary trypsinogen activation peptide (TAP), serum trypsinogen-2, interleukins 1, 6, and 8 have been shown been shown to predict the outcome in severe pancreatitis. [21, 22] It could not be done in the present study because of a resource limited setting.

Limitations of the study

The strength of the study is that it included an adequate number of patients with necessary investigations. It was done in a resource limited setting with no external funding. We could do the minimum required investigations for assessment of acute pancreatitis but could not do other specific markers as mentioned earlier. We could not repeat initial lab values for all patients but we definitely monitored renal function, amylase and lipase for all patients. In view of the above reasons we could not calculate the scores at different times of hospital stay. Though the detailed scoring systems offer significant advantage of risk assessment we could infer that initial lab makers especially CRP, LDH and lipase could be useful for initial triaging and predict morbidity and mortality.

Conclusion

The present study again emphasizes the significance of early assessment of severity and intensive care management in acute pancreatitis. Lab markers with high values of lipase, CRP and LDH correlated well with the mortality and morbidity. CRP and LDH at admission could be important prognostic markers for predicting morbidity and mortality in acute pancreatitis.

Table 1.

The study group

| Age in Years ( N) | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| < 20 (3) | 3 | 0 |

| 21–40 (54) | 41 | 13 |

| 41–60 (44) | 35 | 09 |

| > 60 (9) | 4 | 05 |

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. S. Manjunath, Former Professor of Medicine, SRMC, Chennai, India for his guidance to this study. We also thank Mr. Porchelvan for statistical analysis.

There are no conflicts of interests in this study and no external funding involved.

References

- 1.Singh VK, Bollen TL, Wu BU, et al. An assessment of the severity of interstitial pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:1098. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beger HG, Rau BM. Severe acute pancreatitis: Clinical course and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5043. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i38.5043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forsmark CE, Baillie J AGA Institute Clinical Practice and Economics Committee, AGA Institute Governing Board. AGA Institute technical review on acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2022. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1400. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013;13:e1. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2013.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Windsor JA. A better way to predict the outcome in acute pancreatitis? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1671. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wu BU, Banks PA. Clinical management of patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1272. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chauhan S, Forsmark CE. The difficulty in predicting outcome in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:443. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson CD, Abu-Hilal M. Persistent organ failure during the first week as a marker of fatal outcome in acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2004;53:1340. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.039883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robert JH, Frossard JL, Mermillod B, et al. Early prediction of acute pancreatitis: prospective study comparing computed tomography scans, Ranson, Glasgow, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II scores, and various serum markers. World J Surg. 2002;26:612. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0278-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yadav D, Agarwal N, Pitchumoni CS. A critical evaluation of laboratory tests in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1309. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bollen TL, Singh VK, Maurer R, et al. A comparative evaluation of radiologic and clinical scoring systems in the early prediction of severity in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:612. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu BU, Bakker OJ, Papachristou GI, et al. Blood urea nitrogen in the early assessment of acute pancreatitis: an international validation study. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:669. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lankisch PG, Weber-Dany B, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB. High serum creatinine in acute pancreatitis: a marker for pancreatic necrosis? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1196. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartwig W, Maksan SM, Foitzik T, et al. Reduction in mortality with delayed surgical therapy of severe pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:481. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(02)00008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.vanSantvoort HC, Bakker OJ, Bollen TL, et al. A conservative and minimally invasive approach to necrotizing pancreatitis improves outcome. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1254. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard TJ, Patel JB, Zyromski N, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality rates in the surgical management of pancreatic necrosis. J GastrointestSurg. 2007;11:43. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mortelé KJ, Girshman J, Szejnfeld D, et al. CT-guided percutaneous catheter drainage of acute necrotizing pancreatitis: clinical experience and observations in patients with sterile and infected necrosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:110. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1116. 144:1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freeman ML, Werner J, van Santvoort HC, et al. Interventions for necrotizing pancreatitis: summary of a multidisciplinary consensus conference. Pancreas. 2012;41:1176. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318269c660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, et al. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayumi T, Inui K, Maetani I, et al. Validity of the urinary trypsinogen-2 test in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2012;41:869. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182480ab7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang QL, Qian ZX, Li H. A comparative study of the urinary trypsinogen-2, trypsinogen activation peptide, and the computed tomography severity index as early predictors of the severity of acute pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:1295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]