Abstract

Background: The goal of this study was to compare operative mortality and actuarial survival between patients presenting with and without hemodynamic instability who underwent repair of acute Type A aortic dissection. Previous studies have demonstrated that hemodynamic instability is related to differences in early and late outcomes following acute Type A dissection occurrence. However, it is unknown whether hemodynamic instability at the initial presentation affects early clinical outcomes and survival after repair of Type A aortic dissection. Methods: A total of 251 patients from four academic medical centers underwent repair of acute Type A aortic dissection between January 2000 and October 2010. Of those, 30 presented with hemodynamic instability while 221 patients did not. Median ages were 63 years (range 38-82) and 60 years (range 19-87) for patients presenting with hemodynamic instability compared to patients without hemodynamic instability, respectively (P = 0.595). Major morbidity, operative mortality, and 10-year actuarial survival were compared between groups. Results: Operative mortality was profoundly influenced by hemodynamic instability (patients with hemodynamic instability 47% versus 14% for patients without hemodynamic instability, P < 0.001). Actuarial 10-year survival rates for patients with hemodynamic instability were 44% versus 63% for patients without hemodynamic instability (P = 0.007). Conclusions: Hemodynamic instability has a profoundly negative impact on early outcomes and operative mortality in patients with acute Type A aortic dissection. However, late survival is comparable between hemodynamically unstable and non-hemodynamically unstable patients.

Keywords: Aortic dissection, Hemodynamics, Surgery

Introduction

Acute Type A aortic dissection exists as a medical crisis with heightened mortality attributable to an increased risk of aortic rupture or malperfusion [1–10]. Patients presenting with hemodynamic instability after Type A aortic dissection have been documented to have excessive operative mortality ranging from 31.4% to 55% [11]. This operative mortality is not different from medical management alone, which has been cited as high as 60% in-hospital [8,9]. There is a paucity of studies investigating the effect of hemodynamic instability on early clinical outcomes and late survival, as well as the importance of surgical decision making in patients with acute Type A aortic dissection. Our study sought to evaluate whether patients presenting with hemodynamic instability have worse early clinical outcomes and late actuarial survival following repair of acute Type A aortic dissection compared to patients presenting without hemodynamic instability.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Databases at Beth Israel Deaconess, Carolinas Medical Center, Missouri Baptist Medical Center, and Meijer Heart and Vascular Institute were queried to identify all patients who underwent repair of aortic dissection between January 2000 and October 2010. A total of 251 patients underwent repair for acute Type A aortic dissections. Of those, 30 presented with hemodynamic instability and 221 presented without hemodynamic instability. Patients who presented with a Type A dissection but did not have surgery were excluded.

A preoperative diagnosis of aortic dissection was accomplished using computed tomographic angiography (CTA) or transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). The diagnosis was later confirmed at the time of operation. A database was created for entry of demographics, procedural data, and preoperative outcomes. These were prospectively entered by dedicated data-coordinating personnel. Long-term survival data were obtained from the Social Security Death Index (http://www.genealogybank.com/gbnk/ssdi/). Follow-up was 97% complete.

Prior to this analysis, study approval from the Institutional Review Board of each center was obtained. Consistent with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), patient confidentiality was consistently maintained.

Definitions

Definitions for this study were obtained from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons' national cardiac surgery database (available online at http://www.sts.org). Hemodynamic instability was defined as hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 80 mm Hg) or the presence of cardiac tamponade, shock, acute congestive heart failure, myocardial ischemia, and/or infarction. Acute Type A dissection was defined as any dissection involving the ascending aorta with presentation within 2 weeks of symptoms. Cerebrovascular accident was defined as a history of central neurological deficit persisting for more than 24 hours. Diabetes was defined as a history of diabetes mellitus regardless of duration of disease or need for antidiabetic agents. Prolonged ventilation was defined as pulmonary insufficiency requiring ventilatory support. Operative mortality includes all deaths occurring during the hospitalization in which the operation was performed (even if death occurred after 30 days from the operation), and those deaths occurring after discharge from the hospital, but within 30 days of the procedure.

Operative Technique

The surgical approach did not differ between patients presenting with and without hemodynamic instability. The diagnosis of Type A aortic dissection was confirmed by TEE intraoperatively for all patients. Access was provided via a median sternotomy. Total cardiopulmonary bypass was initiated with venous cannulation of the right atrium and arterial cannulation of the femoral or right axillary artery. Myocardial protection was ensured by cold blood cardioplegia administration through an antegrade approach via the ostia of the coronary arteries and/or a retrograde approach through the coronary sinus. Access through the right superior pulmonary vein was utilized for vent placement in the left ventricle. The aortic root was restored by resection of the intimal tear followed by replacement of the ascending aorta and resuspension or repair of the aortic valve. The aortic clamp was removed and the aortic arch was inspected after attaining a mean cooling temperature range of 15 to 18°C. The distal anastomosis was then completed and antegrade aortic perfusion was established. Patients with irreparable damage of the aortic root or valve underwent either a root replacement with a composite valve graft and coronary button reimplantation, or a valve replacement with mechanical or tissue prosthesis. If the aortic root could not be repaired, a root replacement was performed. Reinforcement of the proximal and distal suture lines was accomplished using Teflon (polytetrafluoroethylene) strips. Some patients required biological glue (BioGlue surgical adhesive, Cryolife, Kennesaw, GA) to reapproximate the dissected layers.

Data Analysis

Univariate Analysis. Univariate comparisons of preoperative, operative, and postoperative variables were performed between patients presenting with hemodynamic instability (n = 30) and those presenting without hemodynamic instability (n = 221). Normal distribution of continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables were tested using either the Student t test or the Mann-Whitney test, depending on the distribution of data. Categoric variables were assessed by the χ2 or Fisher exact test, depending on the distribution of the data.

All tests were two-sided and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Survival Analysis. Kaplan-Meier unadjusted survival estimates were calculated and compared for patients presenting with hemodynamic instability versus patients presenting without hemodynamic instability using a log-rank test. All analyses were conducted using SPSS statistical software version 21 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

Preoperative Characteristics

Preoperative characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Creatinine was higher in patients with hemodynamic instability compared to those without hemodynamic instability (P = 0.005).

Table 1.

Preoperative Patient Characteristics

| Variablea | Hemodynamic instability |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 30) | No (n = 221) | P-value | |

| Age (years) | 63 (38-82) | 60 (19-87) | 0.595 |

| Diabetes | 3 (10%) | 14 (6%) | 0.453 |

| Hypertension | 23 (79%) | 175 (80%) | 0.976 |

| Ejection fraction | 55 (35-75) | 55 (15-73) | 0.642 |

| COPD | 1 (3%) | 18 (8%) | 0.799 |

| Creatinine | 1.3 (0.8-3.8) | 1.1 (0.4-12.5) | 0.005 |

| Female gender | 9 (30%) | 70 (32%) | 0.853 |

| Arrhythmias | 5 (17%) | 27 (12%) | 0.493 |

| NYHA class | 0.319 | ||

| I | 3 (14%) | 17 (11%) | |

| II | 2 (9%) | 10 (6%) | |

| III | 1 (4%) | 34 (21%) | |

| IV | 16 (73%) | 101 (62%) | |

| History of cerebrovascular accident | 2 (7%) | 16 (7.2%) | 0.909 |

| Number of diseased vessels | 0.413 | ||

| Zero | 24 (80%) | 191 (87%) | |

| One | 4 (14%) | 12 (5%) | |

| Two | 1 (3%) | 7 (3%) | |

| Three | 1 (3%) | 11 (5%) | |

| EF < 40 | 1 (3%) | 13 (6%) | 0.568 |

Continuous data are shown as median (range) and categoric data are shown as percentage.COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EF = ejection fraction; NYHA = New York Heart Association.

Operative Characteristics

Operative patient characteristics of patients with hemodynamic instability and without hemodynamic instability who underwent repair for acute Type A aortic dissection are presented in Table 2. Patients presenting with hemodynamic instability had a lower cardiopulmonary bypass time compared to patients without hemodynamic instability (P = 0.039). A hemiarch technique was employed more frequently for patients with hemodynamic instability compared to patients without hemodynamic instability (P = 0.002).

Table 2.

Operative Patient Characteristics

| Variablea | Hemodynamic instability |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 30) | No (n = 221) | P-value | |

| CPB time >200 min | 8 (27%) | 92 (42%) | 0.116 |

| CPB time (minutes) | 156 (5-411) | 186 (64-684) | 0.039 |

| Circulatory arrest time (minutes) | 15 (0-73) | 16 (0-90) | 0.591 |

| Aortic valve procedure | 0.609 | ||

| Nothing | 7 (23%) | 55 (25%) | |

| Replacement | 2 (7%) | 19 (9%) | |

| Resuspension | 17 (57%) | 94 (43%) | |

| Aortic root replacement | 4 (13%) | 52 (23%) | |

| Distal anastomotic technique | |||

| Distal with cross-clamp | 5 (17%) | 59 (29%) | 0.156 |

| Open distal | 24 (83%) | 143 (71%) | 0.278 |

| Hemiarch technique | 23 (77%) | 102 (46%) | 0.002 |

| Total arch replacement | 1 (3%) | 24 (11%) | 0.196 |

| Arterial cannulation | 0.340 | ||

| Axillary | 4 (16%) | 46 (26%) | |

| Femoral | 12 (48%) | 86 (50%) | |

| Other | 9 (36%) | 42 (24%) | |

| Retrograde cerebral perfusion | 5 (17%) | 24 (11%) | 0.351 |

| Antegrade cerebral perfusion | 7 (23%) | 56 (25%) | 0.812 |

| Bioglue/Felt Strip | 0.321 | ||

| Bioglue | 14 (47%) | 110 (50%) | |

| Felt strip | 10 (33%) | 43 (20%) | |

| Both | 2 (7%) | 23 (10%) | |

| None | 4 (13%) | 45 (20%) | |

Continuous data are shown as median (range) and categoric data are shown as percentage.CPB = cardiopulmonary bypass.

Postoperative Characteristics

Postoperative characteristics are depicted in Table 3. Operative mortality (47% versus 14%) and cardiac arrest (30% versus 6%) were significantly higher for patients presenting with hemodynamic instability (P < 0.001), compared to patients without hemodynamic instability. More patients with hemodynamic instability experienced acute renal failure (43% versus 17%) compared to patients presenting without hemodynamic instability (P = 0.001).

Table 3.

Postoperative Patient Characteristics

| Variablea | Hemodynamic instability |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 30) | No (n = 221) | P-value | |

| Deep sternal wound infection | 0 | 3 (1%) | 0.521 |

| Prolonged ventilation | 19 (63%) | 96 (47%) | 0.087 |

| Acute renal failure | 13 (43%) | 37 (17%) | 0.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 5 (17%) | 16 (7%) | 0.080 |

| Hemorrhage-related re-exploration | 6 (20%) | 37 (17%) | 0.657 |

| Cardiac arrest | 9 (30%) | 12 (6%) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 5 (17%) | 38 (17%) | 0.943 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 7 (23%) | 52 (25%) | 0.832 |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 15 (0-62) | 10 (0-99) | 0.569 |

| Operative mortality | 14 (47%) | 30 (14%) | <0.001 |

Continuous data are shown as median (range) and categoric data are shown as percentage.

Survival Analysis

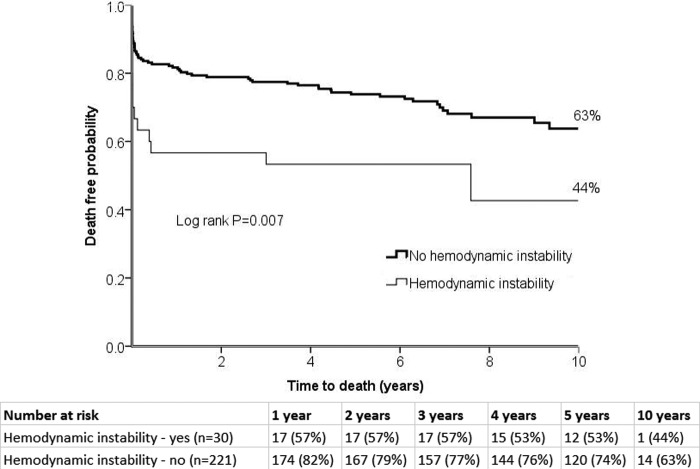

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier survival estimates are presented in Figure 1. There was a difference in the follow up time between groups (p = 0.007). Patients with hemodynamic instability had a median follow-up time of 1542 days (range = 1-4082), while those without hemodynamic instability had a median follow up time of 2154 days (range= 1-4800). Actuarial 10-year survival was lower for patients with hemodynamic instability, compared to those without (44% versus 63%, respectively, log-rank P = 0.007).

Figure 1.

Actuarial unadjusted 10-year survival curves for patients with hemodynamic instability versus patients without hemodynamic instability.

Discussion

Our study is among few studies comparing operative characteristics and early and late postoperative outcomes between patients presenting with and without hemodynamic instability following acute Type A aortic dissection repair. Hemodynamic instability negatively impacted the postoperative outcomes and survival of patients who underwent surgical repair of Type A aortic dissection, compared to hemodynamic instability presentation. These results affirm the notion that patients presenting with hemodynamic instability fare worse than those without hemodynamic instability after surgical repair for acute Type A dissection.

Principal Findings

Operative Mortality. Patients in our study presenting with hemodynamic instability had significantly higher operative mortality rates compared to patients without hemodynamic instability (P < 0.001). Previous studies have also documented worse survival for patients with hemodynamic instability [11,12]. Specifically, Trimarchi et al. [11] documented 31.4% in-hospital mortality among patients with hemodynamic instability compared to 16.7% for stable patients (P < 0.001). The even higher operative mortality for hemodynamically unstable patients in our study could be explained by the fact that Trimarchi et al. [11] consolidated patients with neurologic instability, mesenteric ischemia, and acute renal failure into their hemodynamic instability cohort, whereas our hemodynamic instability cohort did not include patients with neurologic instability or intestinal malperfusion.

Operative Characteristics. Hemodynamically unstable patients had shorter cardiopulmonary bypass time and more hemiarch repairs. The shorter cardiopulmonary bypass time in hemodynamically unstable patients is due to the lower rate of patients requiring aortic root replacements (a more time consuming operation compared to the resuspension or replacement of the aortic valve), compared to the patients without hemodynamic instability. The higher incidence of hemiarch repairs in patients with hemodynamic instability may be attributed to the more extensive aortic dissection in this subset of patients compared to the patients without hemodynamic instability.

Postoperative Outcomes and Survival. Early postoperative outcomes such as atrial fibrillation and stroke rates were comparable between patients with and without hemodynamic instability. However, acute renal failure was higher for patients with hemodynamic instability compared to those without hemodynamic instability, secondary to preoperative hypotension in patients with hemodynamic instability. Actuarial 10-year survival was worse for patients who presented with hemodynamic instability than those without (Fig. 1). However, most of the mortalities in the hemodynamic instability group occurred in the early postoperative phase, compared to the later phase where the differences in survival between groups were less pronounced.

Timing of Surgery versus No Surgery

Our study documented an excessive operative mortality of patients who presented with hemodynamic instability compared to those without. The mortality of patients presenting with hemodynamic instability is similar to the mortality for medical management of patients with Type A aortic dissection, according to recent data documenting a 42% 30-day survival in medically treated acute Type A dissections [7]. Our present data, with a 47% operative mortality in Type A dissection patients presenting with hemodynamic instability, suggests that therapy in this subgroup should be individualized and some patients may be candidates for surgery. However, patients with significant comorbidities may be candidates for medical or possibly delayed surgery.

Clinical Implications

We conducted a multi-institutional observational study to assess the impact of hemodynamic instability on operative characteristics and on short- and long-term outcomes following repair of acute Type A aortic dissection. In this study we examined an unselected cohort of patients from four academic institutions. This is among few studies comparing early clinical outcomes and 10-year actuarial survival between patients with and without hemodynamic instability following repair of acute Type A aortic dissection. In our study, hemodynamic instability adversely affected early clinical outcomes and survival following repair of acute Type A aortic dissection. Based on the results of our study, treatment of patients with hemodynamic instability should be individualized because of the excessive early operative mortality. However, long-term survival is comparable between patients with hemodynamic instability and those without hemodynamic instability.

Study Limitations

Inherent limitations of a retrospective multi-institution investigation unavoidably affected our study. The analysis may also have introduced bias since nine different surgeons from four different institutions performed the operations. Patients who were lost to follow-up were not contacted for this study. Further examination regarding reoperations on the remaining dissected aorta, the causes of late mortality, and the fate of the false lumen were outside the scope of our analysis. These should be the focus of future studies evaluating long-term outcomes of acute Type A aortic dissection repair.

Conclusions

Hemodynamic instability has a profoundly negative impact on early outcomes and operative mortality in patients with acute Type A aortic dissection. However, late survival is comparable between hemodynamically unstable and non-hemodynamically unstable patients.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest relevant to this publication.

References

- 1.Ramanath VS, Oh JK, Sundt TM 3rd, Eagle KA. Acute aortic syndromes and thoracic aortic aneurysm. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:465–481. 10.4065/84.5.465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirst AE Jr, Johns VJ Jr, Kime SW Jr. Dissecting aneurysm of the aorta: a review of 505 cases. Medicine. 1958 Sep;37:217–279. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Kouchoukos NT, Dougenis D. Surgery of the thoracic aorta. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1876–1889. 10.1056/NEJM199706263362606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khandheria BK. Aortic dissection. The last frontier. Circulation. 1993;87:1765–1768. 10.1161/01.CIR.87.5.1765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eagle KA, DeSanctis RW. Aortic dissection. Curr Probl Cardiol. 1989;14:225–278. 10.1016/S0146-2806(89)80010-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goossens D, Schepens M, Hamerlijnck R, Hartman M, Suttorp MJ, Koomen E, et al. Predictors of hospital mortality in type A aortic dissections: a retrospective analysis of 148 consecutive surgical patients. Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;6:76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagan PG, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, Bruckman D, Karavite DJ, Russman PL, et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) - New insights into an old disease. JAMA. 2000;283:897–903. 10.1001/jama.283.7.897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bavaria JE, Brinster DR, Gorman RC, Woo YJ, Gleason T, Pochettino A. Advances in the treatment of acute type A dissection: an integrated approach. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:S1848–S1852. 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)04128-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bavaria JE, Pochettino A, Brinster DR, Gorman RC, McGarvey ML, Gorman JH, et al. New paradigms and improved results for the surgical treatment of acute type A dissection. Ann Surg. 2001;234:336–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melby SJ, Zierer A, Damiano RJ Jr, Moon MR. Importance of blood pressure control after repair of acute type a aortic dissection: 25-year follow-up in 252 patients. J Clin Hypertens. 2013;15:63–68. 10.1111/jch.12024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trimarchi S, Nienaber CA, Rampoldi V, Myrmel T, Suzuki T, Mehta RH, et al. Contemporary results of surgery in acute type A aortic dissection: The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:112–122. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nienaber CA, Fattori R, Mehta RH, Richartz BM, Evangelista A, Petzsch M, et al. Gender-related differences in acute aortic dissection. Circulation. 2004;109:3014–3021. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130644.78677.2C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]