Abstract

We examine cohort trends in premarital first births for U.S. women born between 1920 and 1964. The rise in premarital first births is often argued to be a consequence of the retreat from marriage, with later ages at first marriage resulting in more years of exposure to the risk of a premarital first birth. However, cohort trends in premarital first births may also reflect trends in premarital sexual activity, premarital conceptions, and how premarital conceptions are resolved. We decompose observed cohort trends in premarital first births into components reflecting cohort trends in (1) the age-specific risk of a premarital conception taken to term; (2) the age-specific risk of first marriages not preceded by such a conception, which will influence women’s years of exposure to the risk of a premarital conception; and (3) whether a premarital conception is resolved by entering a first marriage before the resulting first birth (a “shotgun marriage”). For women born between 1920–1924 and 1945–1949, increases in premarital first births were primarily attributable to increases in premarital conceptions. For women born between 1945–1949 and 1960–1964, increases in premarital first births were primarily attributable to declines in responding to premarital conceptions by marrying before the birth. Trends in premarital first births were affected only modestly by the retreat from marriages not preceded by conceptions—a finding that holds for both whites and blacks. These results cast doubt on hypotheses concerning “marriageable” men and instead suggest that increases in premarital first births resulted initially from increases in premarital sex and then later from decreases in responding to a conception by marrying before a first birth.

Keywords: Fertility, Nonmarital births, Marriage, Pregnancy

Introduction

In this article, we present new evidence on trends in premarital first births by decomposing observed trends into three proximate demographic components for cohorts of U.S. white and black women born between 1920 and 1964. Because a premarital birth requires two things—that a child is born and that the mother has never been married—trends in premarital births will reflect trends in the proximate causes of them, such as changes in sexual behavior and birth control, or factors that might account for trends in first marriage. Regarding proximate determinants of fertility, increases in sex prior to marriage would, all else being equal, increase premarital conceptions and thus premarital first births. When and whether women marry is also relevant to trends in premarital first births via two distinct mechanisms not typically distinguished in previous research. A retreat from marriage means that successive cohorts of women will enter first marriage at later ages (or, in the extreme case, not at all), implying increases in the years that women remain never-married and thus exposed to the risk of a premarital conception. All else being equal, this will in turn lead to increases in premarital first births. A decrease in the tendency of couples to marry in response to a premarital pregnancy is, we argue, a behaviorally distinct type of retreat from marriage; it, too, would imply increases in premarital first births, all else being equal.

In this article, we decompose the trend in premarital first births into three components: (1) cohort trends in the age-specific risk of a premarital conception taken to term, (2) cohort trends in the age-specific risk of first marriages not preceded by such a conception, and (3) cohort trends in whether a premarital conception prompts a first marriage that occurs before a first birth.

We depart from the standard albeit colloquial term “shotgun” marriage,” instead using the terms “postconception first marriage” to refer to a first marriage that occurs after conception but before the first birth, and “preconception first marriage” to refer to a first marriage not preceded by conception. We prefer the term “postconception marriage” to “shotgun marriage” because the latter connotes a father who, upon discovering his daughter’s pregnancy, threatens violence if she and her partner do not marry. This imagery presumes that we know whose motivation such marriages reflect. We prefer use of a more descriptive, less assumption-laden term highlighting what is distinctive about a postconception marriage: namely, a specific ordering of events in which marriage comes after a conception but before a birth.1

The relative importance of these three proximate determinants—premarital conceptions and marriages before or after such conceptions—speak indirectly to questions about more distal macrosocial causes of the upward trend in premarital first births. Many sociologists believe that the marriageability of men was the key factor (Wilson and Neckerman 1987); if men are not employed or if they have very low earnings, they are less able to fulfill their traditional role as breadwinner. This could affect premarital first births in two ways. First, if men are less marriageable, the resulting retreat from marriage will imply that women will spend more years never-married and hence exposed to the risk of a premarital pregnancy. Second, marriage retreat may imply that couples will be less likely to marry in response to a premarital pregnancy. Our decompositions are intended to distinguish between these two possibilities and thus to determine the extent to which either of these two types of retreat from marriage contributed to observed trends in premarital first births. Finally, increases in premarital sex would, all else being equal, result in increases in premarital conceptions. Relevant to this, our decompositions are also intended to show the extent to which increases in premarital first births reflect cohort change in age-specific rates of premarital conception during the ages women were never-married.

While it is known that premarital first births have increased steadily for both whites and blacks in recent decades, it is often not fully appreciated how longstanding this trend is. Popular accounts hold that dramatic increases in childbearing outside of marriage started in the 1960s, perhaps as the result of welfare availability or the sexual revolution. As mentioned earlier, sociological accounts also focus on this more recent period and emphasize how deindustrialization reduced the employment, earnings, and hence marriageability of men. None of these accounts square well with what we will document: steady increases in the proportion of black and white women experiencing a premarital first birth, starting with cohorts born as early as 1920, whose first births were typically in the early 1940s. The contribution of our analysis is to shed light on the longstanding nature of the upward trend in premarital births; to examine the role of three proximate demographic determinants in observed trends; and to identify accounts concerning more distal causes that, although untested by our analysis, are consistent with what we find.

Our analysis is possible because the Current Population Surveys (CPS) have, in certain years, included retrospective first-birth and first-marriage histories. The June supplements of 1980, 1985, 1990, and 1995, taken together, provide adequate sample sizes for cohorts of women born from 1920 to 1964. Because these data provide the month and year of first births and first marriages, they allow us not only to identify premarital first births but also to infer whether a first birth was conceived prior to, but took place within, a first marriage. Unfortunately, the June CPS supplements in years after 1995 have not asked about the month and year of first births and marriages, so we do not have adequate sample sizes to extend our analysis to cohorts born after 1965.

Literature Review

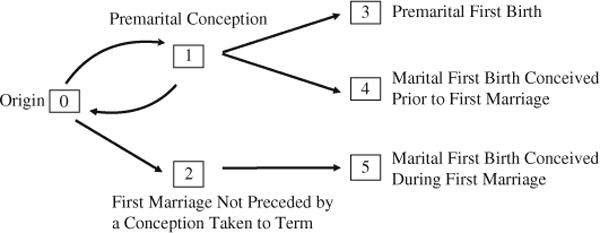

Figure 1 depicts our conceptual model, around which we have also organized our literature review. Arrows depict the possible transitions women may experience. Women begin life in an origin state in which they have never been married, have never had a birth, and are not currently pregnant. Women in the origin state may then experience a premarital conception (0 → 1) or a first marriage not preceded by a conception (0 → 2); they may also remain in the origin state, experiencing neither transition. The reverse arrow from a premarital conception to the origin state (1 → 0) acknowledges that some women who have a premarital conception may return to the origin state because of an induced abortion, a miscarriage, or a fetal death. Women who transition directly to a first marriage (0 → 2) may go on to have a birth, but because our focus is on premarital first births, we do not focus on births conceived within a first marriage. Women who have a premarital conception that is taken to term may give birth outside of formal marriage (1 → 3) or may marry before the birth (1 → 4), yielding premarital and marital first births, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of first births occurring within and outside of a first marriage. Women begin in an origin state (0) in which they have never been married, have not had a birth, and are not currently pregnant. From this origin state, some women may transition to either (1) a premarital conception or (2) a first marriage not preceded by a conception that was subsequently taken to term. The reverse arrow from (1) to (0) denotes the possibility that some women who have a premarital conception may return to the origin state because of an induced abortion, a miscarriage, or fetal death. The model also assumes that those with a premarital conception taken to term will resolve the conception with either (3) a premarital first birth or (4) a first birth following a postconception first marriage. Finally, a marital first birth may occur to women who conceived during a first marriage (5)

Because our analysis will cover trends for cohorts of women born between 1920 and 1964, we focus our review on studies relevant to these cohorts and on factors affecting period trends through the 1980s, when the last of our cohorts typically would have had their premarital first births. We therefore exclude much of the more-recent literature on trends relevant to the 1990s and later. We begin our review with studies of premarital conceptions, premarital sexual activity, and their link to nonmarital fertility.

Descriptive Analyses of Trends in Premarital or Nonmarital Conceptions and Births

Bachu (1999) reported that for white women younger than age 30, the percentage of first births that were conceived before marriage rose from 15 % in the 1930s to 45 % in the early 1990s. For blacks, the comparable estimates were 43 % in the 1930s and 86 % in the 1990s. Bachu used a subset of the June Fertility Supplements to the CPS that we will use, drawing from women’s reports of the calendar month and year of births and marriages, and also assuming (as we will) that births within seven months after marriage were conceived before marriage. Bachu’s results showed steady increases in the percentage of first births that were premaritally conceived from 1945 onwards, but she did not examine the birth cohorts of the mothers having these births, as we will. A limitation of Bachu’s analysis, like ours, is that women were asked about live births only, thus excluding conceptions leading to miscarriages or abortions. We discuss the implications of this limitation later in the article.

Wu (2008) provided life-table estimates, showing that the percentage of white women experiencing any nonmarital birth by age 25 rose from 7 % to 13 % between cohorts born in 1925–1929 and those born in 1960–1964; the analogous increase for blacks was from 24 % to 52 %. He did not limit his analysis to first births or to never-married women, as we will. Wu analyzed cohort trends, as we will. Period trends from vital statistics show that the percentage of all U.S. births that were to unmarried women increased from 4 % of births in 1945 to 33 % in 1999 and to 41 % in 2009 (Hamilton et al. 2010; Ventura and Bachrach 2000).

For conceptual reasons that we explain shortly, our analysis will focus on (1) premarital first births rather than nonmarital births at all parities; (2) trends by the birth cohort of the women giving birth rather than by the period when the births occurred; and (3) the proportion of women who experienced a premarital conception (later taken to term), and the proportion of these women who go on to have a premarital birth (rather than marrying before the birth), as opposed to the conventional ratio of nonmarital births to all births. It is important to recognize, however, that all measures show substantial increases in childbearing outside marriage.2 In our literature review, when dealing with studies examining data on all nonmarital births, we use the broader term “nonmarital”; when talking about studies that limit consideration to those occurring before a first marriage, we use the term “premarital births.” We turn now to research examining the causes of trends in premarital births.

Increases in Premarital Conception Leading to Increases in Premarital First Births

Our analysis isolates how age-specific increases in premarital conceptions (taken to term) have contributed to increases in premarital first births. Because sexual intercourse precedes all births (save some resulting from assisted fertility techniques), changes across cohorts toward earlier age at first intercourse or increases in frequency of premarital sex following onset will, all else being equal, increase premarital conceptions at any given age (Bongaarts and Potter 1983; Davis and Blake 1956).3 Thus, past research on trends in sexual behavior at specific ages is relevant to expectations concerning cohort trends in the age-specific risk of a premarital conception, as well as how such trends will, in turn, affect trends in premarital first births. Increased sexual activity would be particularly likely to lead to increases in premarital conceptions when use of effective birth control was uncommon. Before the 1960s, oral contraceptives (“birth control pills”) were not available, and before the 1970s, abortion was not legal in many states. Prior to these developments, birth control was typically limited to less-effective methods, such as condoms, diaphragms, withdrawal, and illegal abortion.

For women born during the baby boom, it is less obvious that increases in premarital sex would lead to increases in premarital conceptions or births. These women came of age in the 1960s or later, when oral contraceptives and legal abortion became available (Goldin and Katz 2002).4 Thus, on the one hand, these more-effective methods of birth control could have offset any increases in sexual activity across these cohorts of women, loosening the link between sexual activity and premarital conceptions in force for pre–baby boom cohorts. On the other hand, many couples are inconsistent in using birth control, and a majority of mothers refer to their nonmarital pregnancies as “unintended” (Chandra et al. 2005; Edin et al. 2007). Thus, increases in premarital sex may increase premarital conceptions and births somewhat, even in the era of highly effective methods of birth control.

What do we know about trends in premarital sex? Most of what we know relies on studies using retrospective self-report data from surveys that asked respondents their age at first intercourse. Laumann et al. (1994:325), analyzing data on white and black women from the 1992 National Health and Social Life Survey, found no trend in mean age at first intercourse for women born in 1933–1942 and 1943–1952, but declines in mean age for the 1943–1952 and 1953–1962 birth cohorts. Goldin and Katz (2002:753), relying largely on data from the 1982 National Survey of Family Growth, found little net change in whether respondents had had premarital sex by various ages between cohorts born in 1939 and those born in 1945, but found increases in premarital sex thereafter. Hofferth et al. (1987:49, tables 3 and 4), also using the 1982 National Survey of Family Growth, reported little change between those born between 1938–1940 and 1944–1946 but found substantial increases in the proportion of unmarried teens who had experienced intercourse between the cohorts born in 1950–1952 and those born in 1965–1967. All these sources noted increases in the proportion of women having premarital sex by various ages among those born after 1945 or 1950. The limited data in these studies for earlier cohorts do not show a shift to earlier sex between cohorts born between 1933–1942 and 1943–1952 (Laumann et al. 1994) or between 1938 and 1945 (Goldin and Katz 2002; Hofferth et al. 1987). The lack of trend in reports across earlier cohorts could reflect no real change; on the other hand, it is possible that premarital sexual activity was more stigmatized and thus underreported in earlier cohorts. We know of no data extending to cohorts born in the early 1920s. Moreover, past research is silent on trends in the frequency of sexual activity following first intercourse, which would also be relevant to the risk of conception. In sum, it appears that there was an increase in premarital sex for women born after 1945 or 1950, but direct evidence on trends in sexual behavior for earlier cohorts is sparse.

Table 3.

Percentage experiencing a premarital conception by age 25: Observed, predicted, and counter-factual trends for white women and black women, by birth cohort

| Observed | Predicted | Counterfactual

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trend in Premarital Conception? | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Trend in First Marriage | Yes | No | Yes | |

| White Women | ||||

| Birth cohort | ||||

| 1920–1924 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.3 |

| 1925–1929 | 9.7 | 10.1 | 10.4 | 8.1 |

| 1930–1934 | 10.7 | 11.1 | 11.9 | 7.8 |

| 1935–1939 | 13.6 | 13.9 | 14.9 | 7.8 |

| 1940–1944 | 16.5 | 16.2 | 16.8 | 8.0 |

| 1945–1949 | 16.9 | 16.2 | 16.1 | 8.4 |

| 1950–1954 | 16.6 | 16.3 | 15.5 | 8.8 |

| 1955–1959 | 17.0 | 16.9 | 15.3 | 9.2 |

| 1960–1964 | 19.1 | 18.6 | 16.3 | 9.5 |

| Change, born in 1920–1924 to 1945–1949 | 8.9 | 7.9 | 7.8 | 0.0 |

| Change, born in 1945–1949 to 1960–1964 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| Change, overall | 11.1 | 10.3 | 8.0 | 1.2 |

| Black Women | ||||

| Birth cohort | ||||

| 1920–1924 | 32.4 | 34.2 | 34.1 | 34.1 |

| 1925–1929 | 32.0 | 33.6 | 34.6 | 33.1 |

| 1930–1934 | 37.4 | 39.2 | 40.1 | 33.4 |

| 1935–1939 | 43.0 | 44.2 | 43.6 | 34.6 |

| 1940–1944 | 48.2 | 48.4 | 47.0 | 35.3 |

| 1945–1949 | 51.9 | 51.4 | 48.2 | 36.6 |

| 1950–1954 | 52.7 | 52.4 | 47.8 | 37.8 |

| 1955–1959 | 53.8 | 52.9 | 46.3 | 39.5 |

| 1960–1964 | 55.7 | 54.7 | 47.4 | 40.0 |

| Change, born in 1920–1924 to 1945–1949 | 19.5 | 17.2 | 14.1 | 2.5 |

| Change, born in 1945–1949 to 1960–1964 | 3.8 | 3.4 | −0.9 | 3.4 |

| Change, overall | 23.3 | 20.6 | 13.2 | 5.9 |

Notes: Predicted trends are obtained from model estimates for the competing risks of a premarital conception taken to term versus a first marriage not preceded by such a conception. When a counterfactual is labeled “yes” for a factor, the reported estimate lets coefficients for this factor vary with cohort as estimated in our models. When a counterfactual is labeled “no” for a factor, the reported estimate does not let coefficients for this factor vary but instead sets coefficients for this factor to those estimated for women born in 1920–1924.

Table 4.

Percentage experiencing a premarital first birth by age 25: Observed, predicted, and counterfactual trends for white women and black women, by birth cohort

| Observed | Predicted | Counterfactual

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trend in Preconception First Marriage? | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Trend in Premarital Conception? | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Trend in Postconception First Marriage? | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| White Women | ||||||||

| Birth cohort | ||||||||

| 1920–1924 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| 1925–1929 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 3.1 | 4.0 |

| 1930–1934 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 3.2 | 4.9 | 3.3 | 4.6 | 3.1 | 4.8 |

| 1935–1939 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 3.2 | 6.2 | 2.9 | 5.8 | 2.7 | 5.2 |

| 1940–1944 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 3.3 | 6.9 | 2.9 | 6.7 | 2.8 | 5.9 |

| 1945–1949 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 3.5 | 6.7 | 3.0 | 6.7 | 3.0 | 5.8 |

| 1950–1954 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 3.6 | 6.4 | 3.5 | 6.8 | 3.7 | 6.5 |

| 1955–1959 | 8.2 | 8.1 | 3.8 | 6.3 | 4.0 | 7.0 | 4.4 | 7.4 |

| 1960–1964 | 11.0 | 10.7 | 3.9 | 6.7 | 4.8 | 7.7 | 5.5 | 9.4 |

| Change, born in 1920–1924 to 1945–1949 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 3.2 | −0.5 | 3.3 | −0.5 | 2.3 |

| Change, born in 1945–1949 to 1960–1964 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 3.6 |

| Change, overall | 7.7 | 7.3 | 0.5 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 4.3 | 2.0 | 5.9 |

| Black Women | ||||||||

| Birth cohort | ||||||||

| 1920–1924 | 21.3 | 22.3 | 22.3 | 22.3 | 22.3 | 22.3 | 22.3 | 22.3 |

| 1925–1929 | 21.0 | 22.0 | 21.6 | 22.6 | 22.3 | 21.9 | 21.7 | 22.7 |

| 1930–1934 | 26.3 | 27.3 | 21.8 | 26.2 | 23.8 | 25.6 | 23.2 | 27.9 |

| 1935–1939 | 29.2 | 30.1 | 22.6 | 28.5 | 23.3 | 28.9 | 23.6 | 29.7 |

| 1940–1944 | 34.8 | 34.8 | 23.0 | 30.7 | 24.6 | 31.6 | 25.4 | 33.8 |

| 1945–1949 | 37.8 | 37.6 | 23.9 | 31.5 | 25.0 | 33.5 | 26.8 | 35.3 |

| 1950–1954 | 43.6 | 43.5 | 24.7 | 31.2 | 28.4 | 34.2 | 31.4 | 39.8 |

| 1955–1959 | 46.8 | 46.3 | 25.8 | 30.2 | 29.9 | 34.6 | 34.5 | 40.5 |

| 1960–1964 | 51.0 | 50.3 | 26.1 | 30.9 | 31.4 | 35.7 | 36.8 | 43.5 |

| Change, born in 1920–1924 to 1945–1949 | 16.5 | 15.3 | 1.6 | 9.2 | 2.7 | 11.2 | 4.5 | 13.0 |

| Change, born in 1945–1949 to 1960–1964 | 13.2 | 12.7 | 2.2 | −0.6 | 6.4 | 2.2 | 10.0 | 8.2 |

| Change, overall | 29.7 | 28.0 | 3.8 | 8.6 | 9.1 | 13.4 | 14.5 | 21.2 |

Notes: Predicted trends are obtained by combining model estimates from the competing-risk and logistic regression models. When a counterfactual is labeled “yes” for a factor, the reported estimate lets coefficients for this factor vary with cohort as estimated in our models. When a counterfactual is labeled “no” for a factor, the reported estimate does not let coefficients for this factor vary but instead sets coefficients for this factor to those estimated for women born in 1920–1924.

The Retreat From Marriage Leading to Increases in Premarital First Births

The “retreat from marriage” refers to (1) increases in the typical age at first marriage since the 1960s, a trend that holds across race and class groups (Ellwood and Jencks 2004a); and (2) increases in the proportion who never marry, a trend that primarily affects recent cohorts of black women (Goldstein and Kenney 2001). Either form of marriage retreat would imply increases in the proportion of women experiencing a premarital conception because of increases in the years of exposure to the risk of a premarital pregnancy (Bachrach 1998; Espenshade 1985:211–212; Seltzer 2000). Note that the increases in premarital conceptions as a result of increased years of exposure to risk would occur even if there were no change in premarital sexual or contraceptive behaviors, and thus would hold even if there were no change across cohorts in the age-specific risk of a premarital conception.

An important paper by Smith et al. (1996) suggested that the retreat from marriage was pivotal in the rise of nonmarital births. To understand the relevance of their paper to the retreat from marriage, consider that absent a trend in divorce, the retreat from marriage reduces the proportion of the population that is married. Using the decomposition method developed by Das Gupta (1993), they decomposed period trends in the nonmarital fertility ratio—that is, the proportion of all births that are nonmarital—into several components, including the proportion of women who are unmarried at each age, the age-specific birth rates of unmarried women, and the age-specific birth rates of married women. For blacks, they found that period increases in the proportion of women who were unmarried accounted for nearly the entire increase between 1960 and 1992 in the proportion of black births that were outside marriage. For whites, declining marriage was also a large factor after 1975, but the rise in birth rates of unmarried women was even more important.5 (For comparison, in our analysis of premarital first births to women born in 1920–1964, most births were between approximately 1940 and 1985, whereas their analysis dealt with births between 1960 and 1992.)6 Their finding of a strong role for the proportion married in determining the nonmarital birth ratio could be driven at least in part by trends toward later age at first preconception marriage. But because they included all nonmarital births, the “proportion unmarried” component of their decomposition could also reflect increases in divorce or decreases in remarriage. Moreover, because they did not distinguish between marital births conceived before marriage and those conceived within marriage, their decompositions do not disentangle the role of these two types of first marriage, and the proportion of the trend in the nonmarital birth ratio that they attribute to change in the proportion of women married may reflect changes in resolving premarital pregnancies with postconception marriages.

Social scientists have offered many explanations for the retreat from marriage, but these explanations typically do not distinguish between preconception and postconception marriage. Economists, following Gary Becker’s specialization model, have argued that marriage declines when women are more economically independent of men, owing to increased availability or generosity of welfare or to women’s increased relative earnings (e.g., Moffitt 2000), but available evidence does not strongly support this claim.7 Consistent with either economic motives for specialization or social norms dictating that men are to be breadwinners is the hypothesis that declines in men’s employment or earnings will render them less “marriageable” (Wilson and Neckerman 1987). However, a large literature has found very uneven evidence for the importance of this factor in the retreat from marriage.8 A recent qualitative literature in sociology describes changes in cultural conceptions of marriage that set a higher relational and economic bar for marriage than previously, and speculates that these changes explain the retreat from marriage, making it a desired but unapproachable status, especially for those with low income (Cherlin 2004; Edin and Kefalas 2005; England and Edin 2007:13–14; Furstenberg 1976, 2007).

It is beyond the scope of this article to determine the cause of the well-documented retreat from marriage. Instead, our contribution is to assess the relative importance for explaining increases in premarital births of increases in the age-specific risk of conceptions, and the two distinct types of marriage retreat: (1) the retreat from early preconception first marriage, which led to increases in the typical age at first marriage and hence to increases in the years women remain exposed to the risk of a premarital conception; and (2) the retreat from the custom of responding to premarital pregnancies with a postconception first marriage. The retreat from the two distinct types of marriage—preconception and postconception—affects trends in premarital first births in distinct ways. Although the retreat from preconception marriage increases the odds that women have premarital births by lengthening their period of exposure to the risk of premarital conceptions, the retreat from postconception marriage increases the odds that women have premarital births by reducing the proportion of premaritally pregnant women who marry before the birth. One reason that the distinction between the two types of marriage is important is its relevance to the plausibility of the claim that the rise in premarital births reflects the deteriorating economic status and thus marriageability of men. If successive cohorts of women encountered fewer marriageable males, we would expect a reduction in both preconception and postconception first marriage—or, if there were a difference, to reduce preconception first marriage more than postconception first marriage, because postconception marriage is more likely to be a response to stigma. Thus, if we were to find that the increase in premarital first births across some range of cohorts is driven mostly by declines in the propensity to resolve premarital pregnancies with postconception marriages, this would cast doubt on trends in men’s employment and earnings as an explanation for trends in premarital births.

Since the 1960s, postconception marriage has declined steeply among both whites and blacks, as evidenced by declines in the proportion of premarital pregnancies that are resolved by the couple marrying before the birth (Akerlof et al. 1996; Bachu 1999; Parnell et al. 1994). Bachu (1999) found that among those taking a premarital first pregnancy to term before age 30, there was little or no trend in postconception marriage between the 1930s and the 1960s but sharp declines thereafter. Among white women with a premaritally conceived first birth, 68 % married before the birth in the early 1960s, but only 29 % did by the early 1990s. The analogous drop for blacks was from 26 % to 10 %.

The analysis by Akerlof et al. (1996) of declines in the proportion of nonmarital conceptions prompting a marriage before the birth is of particular interest because it attempted to estimate the number of nonmarital conceptions in a way that corrected for the known underreporting of abortions in surveys (Fu et al. 1998; Jones and Kost 2007). The authors added estimates of numbers of abortions to unmarried women from surveys of abortion providers to nonmarital births reported in the National Survey of Family Growth to estimate of the number of nonmarital conceptions in each year. The analysis of Akerlof et al. (1996), which used a period framework classifying events by the year of the conception, showed large declines in the percentage of nonmarital pregnancies in which the couple married before the birth. Further, the authors calculated that this decline accounts for about three-fifths of blacks’ increase and three-fourths of whites’ increase in nonmarital births between the mid-1960s and the late 1980s.

Akerlof et al. argued that it was the advent of oral contraceptives in the 1960s and the legalization of abortion in 1973 that undermined the norms that upheld the custom of marrying in response to a conception. In their view, once women could contracept effectively or abort a pregnancy, men felt less obligated to marry a pregnant partner. Most other authors, though, have stressed that women as well as men have come to doubt that an impending birth is sufficient reason to marry (Edin and Kefalas 2005; Furstenberg 1976). This change by both women and men in their view of the appropriateness of marrying because of a pregnancy may reflect the aforementioned cultural change toward a higher relational and economic bar to marriage that may well affect both preconception and postconception marriages (Cherlin 2004), women’s higher employment, or the declining marriageability of men (Edin and Kefalas 2005; Wilson and Neckerman 1987). It is also possible that much of the stigma associated with a premarital birth was that it revealed that the woman was sexually active while unmarried. If so, then the greater prevalence of premarital sex would presumably weaken the stigma associated with premarital sex, giving couples encountering a pregnancy one less reason to marry.

Data

We analyze data from the retrospective marital and fertility histories from the June 1980, 1985, 1990, and 1995 Current Population Survey (CPS). The CPS sample universe consists of the U.S. noninstitutional civilian population aged 15 and older and hence provides a nationally representative sample of U.S. women (and of their births) spanning a long historical period. The June 1980, 1985, 1990, and 1995 CPS contain additional questions on fertility and marriage asked of married women aged 15 or older and never-married women aged 18 or older.9 The June supplements began by asking respondents about their marital history, including the calendar month and year of first marriage. After providing retrospective marital histories, respondents were then queried about their childbearing histories. Women were prompted for the dates of birth (in calendar month and year) for their first four and most recent child, from which we construct the date (calendar month and year) of a first birth.

These questions about the dates of women’s first marriage and first births allow us to identify premaritally conceived births. To identify such births, we invoke the strong assumption that the conception occurred nine months prior to the birth for all such births. As is common in the literature, we then employ a definition of a premaritally conceived, but postmarital, first birth as a first birth occurring less than seven months after a first marriage. We assume that all first births occurring at seven or more months following a first marriage were conceived within rather than before the marriage. This in effect assumes that births seven or eight months after a first marriage are premature, rather than conceived before the marriage.

Our approach also assumes that women truthfully provide the dates of their first births and marriages. The interview questions provided no lead-in instructions that would alert respondents to the substantive content on marriage and fertility in the June supplement. The standard CPS items (e.g., labor force participation, hours worked) were followed immediately by the marital and fertility supplement, with a woman’s marital history obtained before her fertility history. Thus, because respondents had no knowledge while responding to the marital history items that these items would be followed by a fertility history, this ordering plausibly reduces the possibility that women underrepresented premaritally conceived births by altering their reported month and year of marriage.10

Another clear limitation of these data is that we have information on births but not on pregnancies ending in a miscarriage or abortion. These data limitations mean that we, like many others, can examine only those conceptions that are taken to term. (For brevity, we sometimes omit the qualifier “taken to term” when discussing conceptions.)

Our data also lack information on cohabitation, so we cannot determine, for example, whether women experiencing a premarital conception were cohabiting at the time of conception—or, in cases where they did not marry during the pregnancy, whether they were cohabiting at birth. This limits our analyses to whether conceptions and births were within or outside formal marriage.11

The CPS employs no oversampling of racial or ethnic minorities; however, the very large sample sizes provide sufficient sample sizes in analyses even when stratifying by race and cohort. Unweighted estimates are presented throughout.

Models and Methods

We limit our analysis to first marriages and first births for analytical tractability, because this approach yields a straightforward competing-risk hazard model and allows us to compare successive cohorts of women at a similar stage in their life cycle. For the birth cohorts we examine, approximately 75 % of all premarital conceptions taken to term involved first births, and approximately 90 % of all marriages occurring between a nonmarital conception and a birth were first marriages.12

Our analyses proceed in two stages. In the first stage, we model cohort change in women’s age-specific risk of a premarital conception versus a preconception first marriage using a standard continuous-time competing-risk proportional hazard model. Because our focus is on age-specific risks, we analyze a woman’s age (rather than calendar date) at the relevant event using a highly flexible specification (for details, see Online Resource 1). The only covariates in the model are cohort dummy variables (1920–1924–1925–1929 … through 1960–1964); our focus is on cohort change as opposed to distinguishing between cohort and period effects. Our first-stage model can thus be viewed as a simple main effects model, with main effects of age (via two competing-risk baseline hazards) and birth cohort affecting the age-specific hazard rate for each competing risk. As we discuss shortly, this “main effects” specification provides a good fit to observed cohort trends, and fit was not notably improved by adding interactions between age and cohort (results not shown). We perform separate analyses for black and white women.

Our competing-risk model makes the usual conditional independence assumption that the two risks are independent, conditional on the covariates in the model. Particularly strong is the assumption that for a given cohort, the likelihood of a first (preconception) marriage does not influence how assiduously couples seek to avoid a premarital conception (via abstinence or contraception). We recognize that this may be a problematic assumption, but we are unaware of a viable alternative strategy for these birth cohorts and outcomes that would avoid this assumption.13

Our second-stage analyses are performed only on those women who experienced a premarital conception subsequently taken to term. We use logistic regression to model whether those women marry before the birth or have a premarital first birth. Again, we use separate models for black and white women. Because there is only limited variation in women’s ages at first birth and first marriage in this second stage, and because the distinction between marrying in an earlier or later month during the pregnancy is of little interest to us, we use a simpler logistic regression approach—as opposed to a continuous-time hazard framework—to model whether the premarital conception leads to a postconception marriage before the birth or to a premarital first birth. We again model cohort change by specifying the same series of dummy variables for respondent’s year of birth. We enter age simply as two dummy variables indicating whether the woman is less than 18 years of age (the reference), 18–20, or older than 20 at conception, given that her age may influence her tendency to marry before the birth.14

In both stages of our analysis, the key independent variable is cohort; our goal is to assess cohort trends in age-specific risks of preconception marriage; premarital conception; and, for those with a premarital conception, the likelihood of marrying between conception and birth. Our estimates of cohort trends may reflect a combination of period and cohort effects; we do not attempt to distinguish between them.15

When interpreting cohort trends, it is helpful to know the typical age at which women had a first premarital birth because it reveals the approximate calendar year in which the births occurred. For whites, the average age was age 20 for the first three cohorts and age 19 for all later cohorts. For blacks, it was age 19 for all except the last (1960–1964) cohort, when it was age 18 (results not shown). Given that average age at first premarital birth is approximately 19–20, women in what we term the “pre–baby boom cohorts” (born in 1920–1924 to 1945–1949) experienced their premarital first births largely in the 1940s through 1960s, whereas those in the “baby boom cohorts” (born in 1945–1949 to 1960–1964) had their premarital first births roughly between 1965 and 1985.16

Although our model is conceptually straightforward, it is not straightforward to interpret coefficients from and across the resulting competing-risk hazard and logistic regressions. To aid interpretability, we use estimated coefficients from our first stage to derive the percentage of women in a given birth cohort who, by age 25, are predicted to experience (1) a premarital conception subsequently taken to term, (2) a first marriage not preceded by such a conception, or (3) neither of these outcomes. We chose to examine probabilities by age 25 because the vast majority of the premarital first births occur by this age.17 We then turn to our second-stage logistic regression analysis, which includes only those women whose first births resulted from a premarital conception taken to term. We use estimated coefficients from this second stage to obtain the percentage of women in a given birth cohort who are predicted to resolve a premarital conception within or outside a first marriage. We then use these first-and second-stage probabilities to estimate the percentage of women with a premarital first birth.18 For additional details, see Online Resource 2.

A further advantage of deriving predicted percentages from our estimated model coefficients is that it allows us to examine counterfactual trends: for example, what trends in premarital first births would have been if there had been no retreat from preconception marriage. This allows us to examine counterfactuals positing trends in some factors but no trends in other factors. For example, we operationalize a counterfactual of no retreat from (preconception) first marriage by constraining age-specific first-marriage risks for all cohorts to equal the age-specific first-marriage risks estimated for one particular cohort—namely, the cohort born in 1920–1924—while letting other factors trend as estimated. Under the assumptions that we note earlier, this allows us to decompose cohort trends in premarital conceptions and premarital first births into components attributable to (1) cohort trends in premarital conceptions; (2) the retreat from marriage as it is usually postulated (i.e., cohort trends in preconception first marriage, which will affect the years that women are exposed to the risk of a premarital conception); and (3) cohort trends in whether a premarital conception is resolved by a postconception marriage or by a premarital first birth.

Results

Cohort Trends in Premarital Conceptions

Table 1 reports the observed percentage of women in each birth cohort who, by age 25, had experienced one of the following mutually exclusive alternatives: (1) a first marriage not preceded by a conception taken to term, (2) a premarital conception taken to term and resolved by a postconception first marriage before the first birth, (3) a premarital conception leading to a premarital first birth, or (4) none of the preceding.

Table 1.

Observed trends for white women and black women, by birth cohort, in the percentage by age 25 experiencing (1) a premarital conception resulting in a first birth within or outside of a first marriage, (2) a first marriage not preceded by such a conception, or (3) neither

| Neither | Preconception First Marriage | First Births From Premarital Conceptions Taken to Term

|

Total | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postmarital Birth | Premarital Birth | |||||

| White Women | ||||||

| 1920–1924 | 21.0 | 71.0 | 4.7 | 3.3 | 100.0 | 7,539 |

| 58.4 | 41.6 | 100.0 | 606 | |||

| 1925–1929 | 17.3 | 73.0 | 6.0 | 3.7 | 100.0 | 10,337 |

| 62.0 | 38.0 | 100.0 | 1,002 | |||

| 1930–1934 | 14.6 | 74.8 | 6.4 | 4.3 | 100.1 | 11,706 |

| 59.8 | 40.2 | 100.0 | 1,244 | |||

| 1935–1939 | 13.5 | 72.8 | 8.8 | 4.8 | 99.9 | 12,150 |

| 64.6 | 35.4 | 100.0 | 1,662 | |||

| 1940–1944 | 14.5 | 69.0 | 10.7 | 5.8 | 100.0 | 14,674 |

| 64.8 | 35.2 | 100.0 | 2,423 | |||

| 1945–1949 | 16.8 | 66.3 | 10.9 | 6.0 | 100.0 | 18,077 |

| 64.4 | 35.6 | 100.0 | 3,065 | |||

| 1950–1954 | 22.8 | 60.6 | 9.7 | 6.9 | 100.0 | 20,139 |

| 58.3 | 41.7 | 100.0 | 3,344 | |||

| 1955–1959 | 28.0 | 55.0 | 8.8 | 8.2 | 100.0 | 15,689 |

| 51.7 | 48.3 | 100.0 | 2,664 | |||

| 1960–1964 | 31.6 | 49.2 | 8.1 | 11.0 | 99.9 | 9,766 |

| 42.4 | 57.6 | 100.0 | 1,871 | |||

| Black Women | ||||||

| 1920–1924 | 21.4 | 46.1 | 11.1 | 21.3 | 99.9 | 709 |

| 34.3 | 65.7 | 100.0 | 230 | |||

| 1925–1929 | 17.1 | 51.0 | 11.0 | 21.0 | 100.1 | 1,101 |

| 34.4 | 65.6 | 100.0 | 352 | |||

| 1930–1934 | 16.1 | 46.5 | 11.1 | 26.3 | 100.0 | 1,469 |

| 29.7 | 70.3 | 100.0 | 549 | |||

| 1935–1939 | 16.3 | 40.6 | 13.8 | 29.2 | 99.9 | 1,533 |

| 32.1 | 67.9 | 100.0 | 660 | |||

| 1940–1944 | 16.1 | 35.7 | 13.4 | 34.8 | 100.0 | 1,767 |

| 27.8 | 72.2 | 100.0 | 852 | |||

| 1945–1949 | 16.3 | 31.8 | 14.1 | 37.8 | 100.0 | 2,353 |

| 27.2 | 72.8 | 100.0 | 1,221 | |||

| 1950–1954 | 20.4 | 27.0 | 9.1 | 43.6 | 100.1 | 2,769 |

| 17.3 | 82.7 | 100.0 | 1,458 | |||

| 1955–1959 | 25.6 | 20.5 | 7.0 | 46.8 | 99.9 | 2,363 |

| 13.0 | 87.0 | 100.0 | 1,273 | |||

| 1960–1964 | 26.6 | 17.7 | 4.7 | 51.0 | 100.0 | 1,528 |

| 8.5 | 91.5 | 100.0 | 852 | |||

Table 2 collapses the categories in Table 1, showing the percentage of women in each cohort experiencing preconception first marriage, premarital conception (whether taken to term as a premarital first birth or within a postconception first marriage), or neither; it also compares predictions from our first-stage analyses with their observed counterparts in Table 1. Observed and predicted percentages are very similar for both white and black women, showing that our first-stage additive specification of age and cohort adequately mirrors observed cohort trends.

Table 2.

Percentage by age 25 experiencing (1) a premarital conception taken to term, (2) a first marriage not preceded by such a conception, or (3) neither: Observed and predicted percentages for white women and black women, by birth cohort

| Neither

|

Preconception First Marriage

|

Premarital Conception

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Predicted | Observed | Predicted | Observed | Predicted | |

| White Women | ||||||

| 1920–1924 | 21.0 | 20.9 | 71.0 | 70.7 | 8.0 | 8.3 |

| 1925–1929 | 17.3 | 17.7 | 73.0 | 72.2 | 9.7 | 10.1 |

| 1930–1934 | 14.6 | 14.9 | 74.8 | 74.0 | 10.7 | 11.1 |

| 1935–1939 | 13.5 | 13.9 | 72.8 | 72.2 | 13.6 | 13.9 |

| 1940–1944 | 14.5 | 15.5 | 69.0 | 68.3 | 16.5 | 16.2 |

| 1945–1949 | 16.8 | 18.6 | 66.3 | 65.2 | 16.9 | 16.2 |

| 1950–1954 | 22.8 | 22.6 | 60.6 | 61.1 | 16.6 | 16.3 |

| 1955–1959 | 28.0 | 26.9 | 55.0 | 56.2 | 17.0 | 16.9 |

| 1960–1964 | 31.6 | 30.3 | 49.2 | 51.1 | 19.1 | 18.6 |

| Black Women | ||||||

| 1920–1924 | 21.4 | 19.5 | 46.1 | 46.4 | 32.4 | 34.2 |

| 1925–1929 | 17.1 | 17.0 | 51.0 | 49.4 | 32.0 | 33.6 |

| 1930–1934 | 16.1 | 15.3 | 46.5 | 45.5 | 37.4 | 39.2 |

| 1935–1939 | 16.3 | 16.2 | 40.6 | 39.6 | 43.0 | 44.2 |

| 1940–1944 | 16.1 | 15.9 | 35.7 | 35.8 | 48.2 | 48.4 |

| 1945–1949 | 16.3 | 17.8 | 31.8 | 30.9 | 51.9 | 51.4 |

| 1950–1954 | 20.4 | 20.2 | 27.0 | 27.4 | 52.7 | 52.4 |

| 1955–1959 | 25.6 | 24.4 | 20.5 | 22.7 | 53.8 | 52.9 |

| 1960–1964 | 26.6 | 23.6 | 17.7 | 21.7 | 55.7 | 54.7 |

Notes: Predicted trends are obtained from model estimates for the competing risks of a premarital conception taken to term versus a first marriage not preceded by such a conception. See the text and Online Resources 1 and 2 for additional details.

We begin our discussion of results with premarital conceptions. Table 2 shows that for white women, the observed percentage experiencing a premarital conception was 8.0 % for the 1920–1924 cohort, more than doubling to 16.9 % for the 1945–1949 cohort, and then rising slightly to 19.1 % for the 1960–1964 cohort; the analogous increase for black women was from 32.4 % to 51.9 % before the baby boom and to 55.7 % during the baby boom.

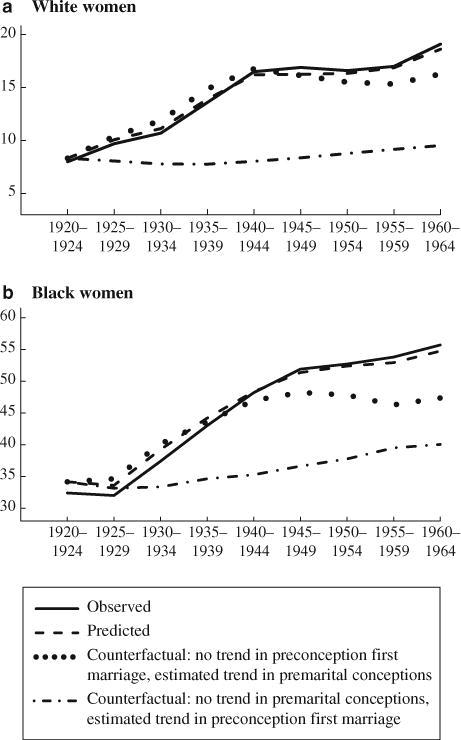

These trends are seen more easily in Fig. 2, which presents observed, predicted, and counterfactual trends in premarital conceptions. The results show that trends for both white and black women are best understood by dividing the cohorts into two groups: (1) the pre–baby boom cohorts (born in 1920–1924 to 1945–1949), most of whom came of age before 1970, and (2) the baby boom cohorts (born in 1945–1949 to 1960–1964), who came of age roughly in 1965–1984. Figure 2a shows that for white women, premarital conceptions taken to term rose sharply for pre–baby boom cohorts but flattened out and then rose much more slowly for the baby boom cohorts. Figure 2b presents results for black women and shows that although levels differ dramatically, trends are strikingly similar for whites and blacks, with dramatic increases in premarital conceptions for pre–baby boom cohorts and much smaller increases for the baby boom cohorts. In interpreting the small increases for the baby boom cohorts, we emphasize that our data reflect only those premarital conceptions that were taken to term. Because we do not observe abortions, it is likely that among both blacks and whites, premarital conceptions actually rose for baby boom cohorts given likely increases in premarital sex.19

Fig. 2.

Observed, predicted, and counterfactual trends in the percentage of women by age 25 experiencing a premarital conception taken to term and resulting in a first birth for white women (panel a) and black women (panel b), by birth cohort. Predicted trends are obtained from model estimates for the competing risks of a premarital conception taken to term versus a first marriage not preceded by conception, as reported in Table 3. The line labeled “Counterfactual: no trend in preconception first marriage, estimated trend in premarital conceptions” refers to a counterfactual trend obtained from estimated cohort trends in premarital conceptions taken to term but imposing a counterfactual of no trend in preconception first marriage (i.e., first marriages not preceded by conceptions). The line labeled “Counterfactual: no trend in premarital conceptions, estimated trend in preconception first marriage” refers to a counterfactual trend obtained from estimated cohort trends in preconception first marriage but imposing a counterfactual of no trend in premarital conceptions taken to term. See the text, Table 3, and Online Resource 2 for additional details

Trends in Premarital Conceptions: Pre–Baby Boom Cohorts

How much of the rise in premarital conceptions for pre–baby boom cohorts is accounted for by the retreat from preconception marriage—that is, by delayed entry into first marriage—which, all else being equal, increases exposure to the risk of a premarital conception? We examine this hypothesis under a counterfactual that allows premarital conceptions to trend as estimated but that posits no trend in preconception first marriage by holding it constant at the level estimated for the 1920–1924 cohort. Figures 2a and 2b show that the resulting counterfactual trend (dotted line) resembles both the observed and predicted trend for premarital conceptions very closely for pre– baby boom cohorts of both white and black women. (There is greater divergence between observed and counterfactual trends for the later baby boom cohorts for black but not white women, a point we will return to.) By contrast, we find little trend in premarital conceptions under a counterfactual that holds such conceptions at their level estimated for the 1920–1924 cohort but that allows preconception marriage to trend as estimated.

Table 3 presents these first-stage counterfactuals in greater detail. For the pre–baby boom cohorts of whites, the percentage experiencing a premarital conception (taken to term) rose from 8.3 % for the 1920–1924 cohort to 16.2 % for the 1945–1949 cohort, as estimated in the model that lets both risks vary with cohort (column labeled “Yes, Yes”). Estimates from the counterfactual that holds preconception first marriage risks at their 1920–1924 level while allowing premarital conceptions to trend as estimated (column labeled “Yes, No”) yields an almost identical increase, from 8.3 % to 16.1 %. By contrast, estimates from the counterfactual of no trend in premarital conceptions but the estimated trend in marriage (column labeled “No, Yes”) produce virtually no trend in premarital conceptions (from 8.3 % to 8.4 %) for pre–baby boom cohorts of white women.

Trends in premarital conceptions as well as the counterfactual that best accounts for them are similar for blacks, despite much higher levels. Estimates of premarital conceptions for pre–baby boom cohorts of black women rose from 34.2 % for women born in 1920–1924 to 51.4 % for the 1945–1949 cohort (column labeled “Yes, Yes”). Most of this increase is accounted for by the counterfactual positing no trend in preconception first marriage but allowing premarital conceptions to trend as estimated (column labeled “Yes, No,” estimated change from 34.1 % to 48.2 %). By contrast, positing no trend in premarital conceptions but allowing preconception first marriage to trend as estimated yields a counterfactual trend that barely rises, from 34.1 % to only 36.6 % between the 1920–1924 and 1945–1949 cohorts of black women.

Thus, for both white and black women, most of the observed trend in premarital conceptions for pre–baby boom cohorts is achieved under a counterfactual of no retreat from marriage—that is, when preconception first marriage is held at its 1920–1924 level while the age-specific risk of premarital conception is allowed to trend as estimated. Conversely, little of the observed trend is achieved under a counterfactual of no trend in age-specific risks of premarital conceptions, while allowing the observed retreat from marriage to trend as estimated. These results thus suggest that the pre–baby boom increase in premarital conceptions is not primarily due to an increase in the number of years women spent never-married and thus exposed to the risk of a premarital conception. Rather, it suggests that increased premarital conceptions resulted from changes in behavior leading to higher conception risks during the ages when women were single and never-married. These results lead us to speculate that premarital sex increased steadily across successive pre–baby boom birth cohorts of both white women and black women, although we also caution that this conclusion is speculative given that our data lack information on premarital sexual behavior.

In the case of whites, one reason why preconception marriage trends cannot account for pre–baby boom cohort trends in premarital conceptions is that, as Table 1 shows, the percentage having a preconception marriage by age 25 was almost as high on the eve of the baby boom as in the earliest cohort (71.0 for those born in 1920–1924, rising to 74.8 for the 1930–1934 cohort, and then steadily falling to 66.3 for the 1945–1949 cohort). For pre–baby boom blacks, we do observe a marked and earlier retreat from marriage. Table 1 shows that for blacks, the percentage having a preconception first marriage by age 25 was 46.1 in the 1920–1924 cohort, increasing to 51.0 in the 1925–1929 cohort, and then dropping steadily to 31.8 in the 1945–1959 cohort. Despite this, our results show that marriage retreat accounts for only a minor share of the upward trend in premarital conceptions for pre–baby boom cohorts of black women (see Fig. 2 and Table 3).

Trends in Premarital Conceptions: Baby Boom Cohorts

We now turn to premarital conceptions for the baby boom cohorts of women. As noted earlier, Figs. 2a and 2b show that premarital conceptions taken to term increased much less rapidly for the baby boom cohorts of women, with Table 3 showing that estimated increases were 2.4 and 3.4 percentage points for whites and blacks, respectively. At the same time, the retreat from marriage was in full force for the baby boom cohorts of women, with Table 2 showing that the estimated percentage of white women having a preconception first marriage by age 25 declined from 65.2 in the 1945–1949 cohort to 51.1 in the 1960–1964 cohort, and from 30.9 to 21.7 among black women.

These underlying trends are mirrored in our counterfactual results. Table 3 shows that for the baby boom cohorts of white women, a counterfactual positing cohort change in the age-specific risk of a premarital conception but no retreat from preconception marriage (row labeled “Change, born in 1945–1949 to 1960–1964,” column labeled “Yes, No”) accounts for only 0.1 of the 2.4 percentage point change from 1945–1949 to 1960–1964 in premarital conceptions, while the counterfactual of marriage retreat but no change in premarital conceptions (column labeled “No, Yes”) accounts for 1.2 of the 2.4 percentage point change. Similarly, for blacks, the counterfactuals involving preconception marriage and conception, respectively, explain none (−0.9) and the entire 3.4 points of the increase in premarital conceptions. Thus, a high proportion of the increase in premarital conceptions for baby boom cohorts of both white and black women is accounted for by the retreat from preconception marriage, which created more exposure to the risk of a premarital conception, but the baby boom increase in conceptions to be explained was very small. Moreover, as we will show, the retreat by baby boom cohorts from preconception marriage does not account for the substantial increase in premarital first births in these cohorts because increases in premarital conceptions (taken to term) are so small.

Trends in Premarital Conceptions: All Cohorts

Trends in premarital conceptions across all cohorts can be summarized as follows. First, cohort trends in premarital conceptions taken to term, as well as their underlying components, are strikingly similar for white and black women, despite equally striking differences in levels. Second, the bulk of the increase in premarital conceptions taken to term occurred for pre–baby boom cohorts of women. Third, this pre–baby boom increase was due primarily to increases in the underlying age-specific premarital conception risks, and not to a retreat from preconception marriage—that is, not to cohort change in the number of years women spent never-married and thus exposed to risk. Fourth, premarital conceptions increased only negligibly for the baby boom cohorts of women; for these cohorts, much of the small increase was due to a retreat from marriage. Taken together, these results lead us to conclude that for both white and black women and across all cohorts considered, the retreat from preconception marriage played a very small role in the overall increase in premarital conceptions taken to term and resulting in a first birth.

Cohort Trends in How Premarital Conceptions Are Resolved

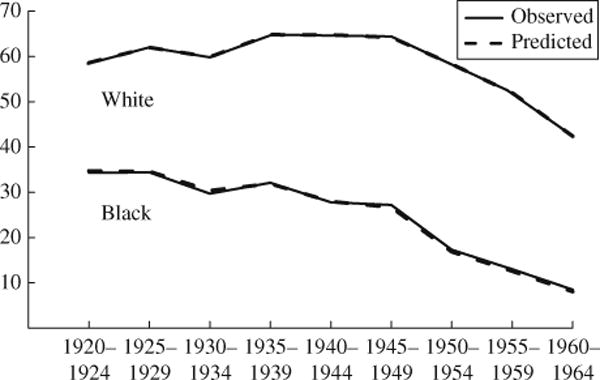

To analyze how premarital conceptions taken to term are resolved, we report cohort trends as estimated from our second-stage logistic regressions for whether premarital conceptions taken to term led to a postconception first marriage or to a premarital first birth. Figure 3 shows cohort trends in the percentage of women with a premarital conception taken to term and resulting in a first birth who entered a first marriage during the first six months of the pregnancy. Observed and predicted percentages are virtually identical, but to avoid any confusion, our discussion refers to the observed percentages.

Fig. 3.

Observed and predicted percentages of white women and black women experiencing a premarital conception by age 25 who marry before the birth, by birth cohort. Predicted trends are obtained from logistic regression model estimates conditional on a premarital conception taken to term. See the text for additional details

For white women, we observe a slight upward trend in resolving a premarital conception by marrying before the first birth, rising from 58.4 % for those born in 1920–1924 to 64.8 % for those born in 1940–1945, and then declining steadily to 42.4 % for the 1960–1964 cohort (Table 1). For black women who took a premarital conception to term, marriages between conception and first birth were always less common than for whites. Among blacks, 34.3 % of premarital conceptions taken to term led to a first marriage before the first birth for those born in 1920–1924, with the ratio declining steadily from a peak of 34.4 % for the 1925–1929 cohort to only 8.5% for the cohort born in 1960–1964 (Table 1). Thus, for both whites and blacks, there was a large retreat from postconception first marriage, particularly among the baby boom cohorts of women. The retreat from postconception first marriage began earlier for blacks than whites, mirroring the earlier black retreat from preconception first marriage.

Cohort Trends in Premarital First Births

We now combine results from our first- and second-stage analyses to examine trends in premarital first births. Figure 4 provides the observed and predicted trends in premarital first births, with the latter combining first- and second-stage estimates; observed and predicted trends match closely. These results are also shown in Table 4, which shows that estimated premarital first births increased nearly monotonically for both white and black women, from 3.4 % by age 25 for white women in the 1920–1925 cohort to 5.8 % of those born in 1945–1949 to 10.7 % of those in the 1960–1964 cohort; the analogous percentages for black women are 22.3 %, 37.6 %, and 50.3 %.

Fig. 4.

Observed and predicted percentages of white women and black women experiencing a premarital first birth by age 25, by birth cohort. Predicted trends are obtained by combining model estimates from the competing-risk and logistic regression models, as reported in Table 4. See the text and Online Resources 1–3 for additional details

We turn next to various counterfactuals in Table 4 to examine the role of three factors in accounting for increases in premarital first births: (1) increases in the age-specific risk of a premarital conception taken to term; (2) the retreat from preconception first marriage, which increased years of exposure to the risk of a premarital conception; and (3) the retreat from postconception first marriage. Our counterfactuals again proceed by holding constant some of these factors at their 1920–1924 levels while allowing others to vary as estimated. We first discuss results for pre–baby boom cohorts and then turn to results for baby boom cohorts.

Trends in Premarital First Births: Pre–Baby Boom Cohorts

The preceding results show that premarital conceptions for pre–baby boom cohorts increased substantially, but that these increases were not due to increased exposure to risk of a premarital conception resulting from the retreat from preconception marriage. The same pattern holds for premarital first births, with increased exposure to the risk of a premarital conception resulting from the retreat from preconception marriage having little effect on trends in premarital first births for pre–baby boom cohorts. The column in Table 4 labeled “No, Yes, No” reports trends for the counterfactual holding preconception and postconception first marriage at their 1920–1924 cohort levels but allowing premarital conceptions taken to term to vary as estimated. Under this counterfactual, we obtain all, and even slightly more than, the predicted trend (column labeled “Yes, Yes, Yes”) in premarital first births for white women; premarital first births increase from 3.4 % to 6.7 % under this counterfactual, with the latter somewhat higher than the predicted 5.8 %. For blacks, this same one-factor counterfactual replicates a majority of the pre–baby boom trend, generating a counterfactual trend of 22.3 % to 31.5 % (an increase of 9.2 percentage points) compared with the predicted trend of 22.3 % to 37.6 % (a 15.3 percentage point increase). By contrast, the other one-factor counterfactuals, which allow either preconception or postconception marriage to trend as estimated, generate counterfactual trends yielding increases of only 1.6 % and 2.7 %, respectively.20

Thus, for pre–baby boom cohorts of both white women and black women, increases in premarital first births arose primarily from increases in the underlying age-specific premarital conception risks, with neither increased exposure spent never-married nor a decline in the propensity of couples to resolve a premarital conception with a postconception first marriage greatly influencing observed trends. The lack of a role for marriage retreat for pre–baby boom whites is perhaps not surprising given that Table 1 shows little net retreat from either preconception or postconception marriage for them. For pre–baby boom blacks, a substantial retreat from preconception marriage did occur; yet, it was not more years of exposure spent never-married that elevated premarital conceptions and premarital first births, but rather increases in the underlying risk of a premarital conception during the ages women in these cohorts spent never-married that account for increases in premarital first births. Thus, perhaps changes in underlying behaviors, such as increases in premarital sexual activity, lie behind pre–baby boom increases in premarital first births for both whites and blacks—a speculation we cannot confirm because we have no direct measures of premarital sexual activity or their trends, nor are such data available for these early cohorts.

Trends in Premarital First Births: Baby Boom Cohorts

For the baby boom cohorts of white women, cohort trends in premarital conceptions do not account for observed increases in premarital first births, contrary to our findings for pre–baby boom whites. This is most easily seen in the one-factor counterfactual (Table 4, column labeled “No, Yes, No”) in which we allow premarital conceptions to vary as estimated but hold preconception and postconception first marriage at their 1920–1925 levels. This counterfactual generates almost no change (0.1 of a percentage point) in premarital first births for baby boom whites, despite a predicted increase of 4.9 %. This is largely because premarital conceptions taken to term increased only slightly in the baby boom cohorts while premarital first births continued climbing. The one-factor counterfactual that most successfully replicates trends allows the resolution of premarital conceptions via postconception marriage to vary as estimated but holds constant the other two factors. This counterfactual (Table 4, column labeled “No, No, Yes”) implies an increase of 1.8 % versus the predicted increase of 4.9 %.21

Results for the baby boom cohorts of black women are similar. Trends in premarital first births for baby boom cohorts of black women were not influenced by increases in premarital conceptions taken to term. Table 4 shows that the counterfactual allowing this one factor to vary across successive baby boom cohorts of black women (column labeled “No, Yes, No”) tracks baby boom trends poorly, implying a 0.6 % decrease in premarital first births, opposite in sign to the predicted increase of 12.7 %. The one-factor counterfactual that most successfully replicates observed trends lets the tendency for couples to resolve a conception by marrying before the first birth vary (column labeled “No, No, Yes”); it implies an increase from 25.0 % to 31.4 %, thus accounting for slightly less than one-half of the predicted increase for baby boom black women.22

Taken together, these results suggest that for both black women and white women born during the baby boom, observed increases in premarital births were driven primarily by a retreat from marriage in response to a premarital conception. The retreat from first marriage not preceded by a conception played almost no role for whites and a nontrivial but, at best, a secondary role for blacks born during the baby boom in the rise in premarital births.

Discussion and Conclusion

The proportion of women experiencing a premarital first birth by age 25 increased steadily for successive cohorts of both white women and black women born between 1920–1924 and 1960–1964. We explored the role of three factors in accounting for this increase: (1) cohort trends in the age-specific risk of a premarital conception taken to term and yielding a first birth; (2) cohort trends in postconception first marriage (i.e., whether a first marriage took place after a premarital conception but before the first birth); and (3) cohort trends in the age-specific risk of a preconception first marriage (i.e., a first marriage not preceded by such a conception), which increases the time successive cohorts of women were exposed to the risk of a premarital conception. Recall that our models make the strong assumption that the risks of premarital conception and preconception marriage are conditionally independent; thus, our conclusions may be sensitive to violations of this assumption. With this caution in mind, we review our findings and conclusions.

For pre–baby boom cohorts of both whites and blacks, who came of age in the 1940s and 1950s, increases across cohorts in the age-specific risk of a premarital conception accounted for virtually all the steady increases in premarital first births. Trends in preconception marriage contributed very little; thus, cohort change in exposure during the ages women were never-married did not account for observed increases premarital first births. Although a retreat from preconception marriage had begun for blacks by the cohort born in 1930–1934 and for whites by the cohort born in 1935–1959, this was not the main force elevating premarital first births for the pre–baby boom cohorts of white women and black women. Rather, virtually all the observed trends in premarital first births can be accounted for by increases across cohorts in risk of a premarital conception experienced during the ages women were single and never-married. Put differently, the increase in premarital first births was not because more women remained never-married at ages like 19 and 20, and thus were at risk of a premarital conception, but rather because among women who had never married at such ages, there were steady increases by cohort in premarital conceptions, which in turn led to increases in premarital first births.

Our finding that increases in premarital births before the baby boom were driven largely by increases in premarital conceptions suggests that there was cohort change in the behaviors leading to a premarital first birth. Absent a decrease in subfecundity, contraceptive use or efficacy, or measurement error, the most likely reason for increases in premarital conceptions and premarital first births that we observe in the pre–baby boom cohorts of both white women and black women is an increase in premarital sexual activity. This conclusion is speculative: our data provide no direct measure of age at first intercourse or the frequency of sexual activity following onset. Still, our conjecture, if correct, implies that at least some aspects of the so-called sexual revolution of the 1960s may instead have been part of a slow evolution of sexual behavior that began much earlier. This is consistent with arguments by historians of sexuality that locate important change in sexual norms and practices as early as the 1920s (D’Emilio and Freedman 1988:239–274). This pre–baby boom sexual evolution may have reflected cultural change regarding the permissibility of premarital sex or changes that weakened the control by parents and other social agents over the sexual behavior of unmarried couples, such as increased urbanization, the rise of the automobile, or earlier exits by youth from the parental home.23

Trends for baby boom cohorts of women—those born in 1945–1959 to 1960–1964, and coming of age in the 1960s to 1980s—show a strikingly different pattern. For these cohorts of both white women and black women, premarital first births increased steadily, yet premarital conceptions taken to term increased only modestly. We speculate that it was the diffusion of effective contraceptive methods (such as oral contraceptives and the legalization of abortion) that allowed declines in women’s age at first intercourse to occur with little simultaneous increase in premarital conceptions. These speculations also highlight a previously discussed limitation of our findings: our lack of data on abortion. Thus, although we found little increase in premarital conceptions taken to term in the baby boom cohorts, we suspect that if we were able to observe all premarital conceptions, including those terminated by abortion, our results would likely show a substantial upward trend in premarital conceptions for white women and black women.

Why, given only small increases in premarital conceptions, did premarital first births rise so markedly for baby boomers? Our results show that a key factor was the decline in the proportion of premaritally pregnant women who married before the birth—in colloquial terms, a decline in “shotgun marriages.”24 Although it is beyond the scope of our analysis to say why this decline occurred, one possibility is that the liberalization of sexual norms removed that part of the stigma of having a premarital birth that came from its revealing that a woman was sexually active before marriage.

Among sociologists, a common view, articulated by Wilson and Neckerman (1987), who were studying African Americans, is that the rising tide of nonmarital births resulted from the declining marriageability of men. This thesis holds that when men are less marriageable because of nonemployment, low wages, or poor job prospects, marriage is delayed or forgone, putting women at risk of a premarital conception for longer, and making marriage a less viable option when a premarital conception does occur. Our data do not contain measures of the employment or earnings of the male partners of the females with premarital conceptions, first births, or first marriages, so our results cannot speak directly to this hypothesis. Nevertheless, our findings cast serious doubt on this account. First, our results suggest a large role for the retreat from postconception marriage but only a small role for the retreat from preconception marriage for baby boom cohorts of both white women and black women. However, if lack of marriageable men was the key driver of premarital births, it is difficult to argue that this factor would affect only postconception, but not preconception, marriage; if anything, we would expect it to affect preconception marriage more because such marriages are not a response to a pregnancy. Second, our results show that neither the retreat from preconception marriage nor the retreat from postconception marriage accounts for the steady increase in premarital first births that occurred for women born before the baby boom. Finally, although levels of premarital first births have long differed dramatically by race, the similarity in the trends for black and white women is hard to square with a male marriageability hypothesis. It is implausible to argue that white men’s marriageability has declined steadily for the cohorts we analyze, which include men coming of age in the 1950s and 1960s, when the economy was booming, wages were rising, and unemployment was generally low.25 These factors lead us to speculate that changes in sexual norms and premarital sexual behavior were more important than economic trends affecting marriage in explaining the long-term rise of premarital first births.

Future research could usefully extend some variant of our approach to more recent cohorts. We know that period trends in the proportion of all births that are outside marriage (Hamilton et al. 2010; Ventura and Bachrach 2000) and in the proportion of women experiencing a premarital first birth (Wu et al. 2001) have continued upward. Yet, much has changed that makes it unclear whether the proximate demographic causes that we identified are still in play. Although we speculated that a rise in premarital sex is the likely explanation for the rise in premarital conceptions for pre– baby boom cohorts of women, it is far less clear whether subsequent trends in premarital sex would be a key factor for more recent cohorts of U.S. women. Indeed, our own findings suggest only a minor role for trends in premarital sex in explaining increased premarital conceptions or premarital births for baby boom cohorts of women. On the one hand, premarital sex among teens and young adults may have become sufficiently ubiquitous as to be irrelevant to trends in premarital first births. On the other hand, others have documented that premarital sex among teen women reversed and trended downward starting in the late 1980s (Abma et al. 2010), with this downward trend argued by some to be an important factor in recent decreases in teen births (Kearney and Levine 2012a). It is also unclear how trends in available methods of contraception and contraceptive behavior have affected conceptions and premarital first births. For example, trends toward increased condom use (Abma et al. 2010; Chandra et al. 2005) will, all else being equal, imply fewer conceptions and births; however, very substantial numbers of nonmarital births continue to be reported as unintended, and many unmarried couples contracept inconsistently (England et al. 2011; Musick et al. 2009). Further, an increasing proportion of nonmarital births are second or higher-parity births, and the proximate determinants of these may be different than for premarital first births. Finally, an increasing proportion of nonmarital births are to cohabiting couples (Bumpass and Lu 2000),26 with some of these cohabitations beginning after the conception (Rackin and Gibson-Davis 2012). Postconception marriage may have become less compelling when postconception cohabitation is an option or when preconception cohabitation itself has become so widespread; thus, its decline may explain some of recent increases in premarital births. On the other hand, the proportion of couples marrying in response to a premarital conception may have already reached levels so low that this factor is now irrelevant for trends in premarital births.27 Consideration of these and other changes will be important to understanding trends in nonmarital childbearing for recent and future cohorts of U.S. women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The first two authors made equal contributions; the order of their names is alphabetical. We gratefully acknowledge funding from National Institute of Child Health and Development to Lawrence Wu (R01 HD29550). We thank Rob Mare, Herb Smith, Phil Morgan, Chris Winship, and the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13524-013-0241-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

A more complete term would be “pre-birth, post-conception marriage,” denoting the order of the three events—conception, marriage, and birth.