Abstract

Introduction

Prevalence of mental health problems are frequently higher within the prison populations than the general population. Previous studies of prison mental health had focused on convict populations whereas, the awaiting trial segment of the prison population in Nigeria has gradually become the majority of the total lock-up. This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence and correlates of mental health problems among the awaiting trial inmates in a prison facility in Ibadan.

Methods

A cross sectional study design was employed to interview 725 awaiting trial inmates of Agodi Prison, Ibadan, Nigeria. A two phase procedure was utilized with initial screening using a socio-demographic questionnaire and the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ −12); followed by a second phase with all high scorers on the GHQ −12 and 10% of the low scorers using the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Inventory (MINI).

Results

A total of 394 respondents participated in the second phase of the study with a mean age of 31.1 years (SD = 8.7), with ages ranging from 18 – 70 years. The mean duration of incarceration at Agodi was 1.1 years (SD = 1.47), with a range of 1 week to 10 years. The prevalence of mental illness was 56.6% with the commonest conditions being depression (20.8%), alcohol dependence (20.6%), substance dependence (20.1%), suicidality (19.8%) and antisocial personality disorder (18%).

Conclusion

There is a high prevalence of neuropsychiatric disorders among awaiting trial inmates but this does not appear to be significantly different from that of convict populations.

Keywords: Awaiting trial inmates, prison, neuropsychiatric disorders, Nigeria

Introduction

The prevalence of mental disorders among prison inmates is significantly higher than the general population globally [1,2] and in Nigeria [3,4], with prevalence rates ranging from 34% to 57%, as compared to a prevalence of 5.8% in the general Nigerian population [5]. Commonly reported mental disorders within prison populations include substance use, depression, and anxiety disorder [3,4].

It is the expected norm that the majority of prison inmates will be convicted offenders while the minority may be remanded inmates awaiting disposal of their cases. However, the past three decades in Nigeria has witnessed an inverted trend in the ratio of convicted prisoners to awaiting trial prisoners. Whereas in 1982, the total lock-up figure for Nigeria was 41,034, with 65% being convicted prisoners [6]; by 2011, this ratio consisted of 71% (36,217) awaiting trial prisoners, out of 50,692 total lock-up figures [7]. In the study site of Agodi Prisons in Ibadan, this ratio was 91.6%, with 764 awaiting trial inmates out of a total lock-up of 834 inmates as at January 2013. Some of these individuals may spend upwards of 10 years awaiting trial; due to their inability to afford lawyers, non-appearance of witnesses and the slow pace of court hearings [8].

The few available studies reporting on the mental health problems within prison populations in Nigeria, had focused almost exclusively on the prevalence and types of mental disorders among convicted prison inmates [3,4]. Currently, there is no evidence that any study has been carried out to evaluate the mental health problems of awaiting trial prison inmates in Nigeria, despite clear evidence that they currently constitute the majority of prison inmates. This study therefore aimed to determine the prevalence, pattern and correlates of mental illness among awaiting trial inmates in Agodi Prisons of Ibadan, Nigeria.

Methodology

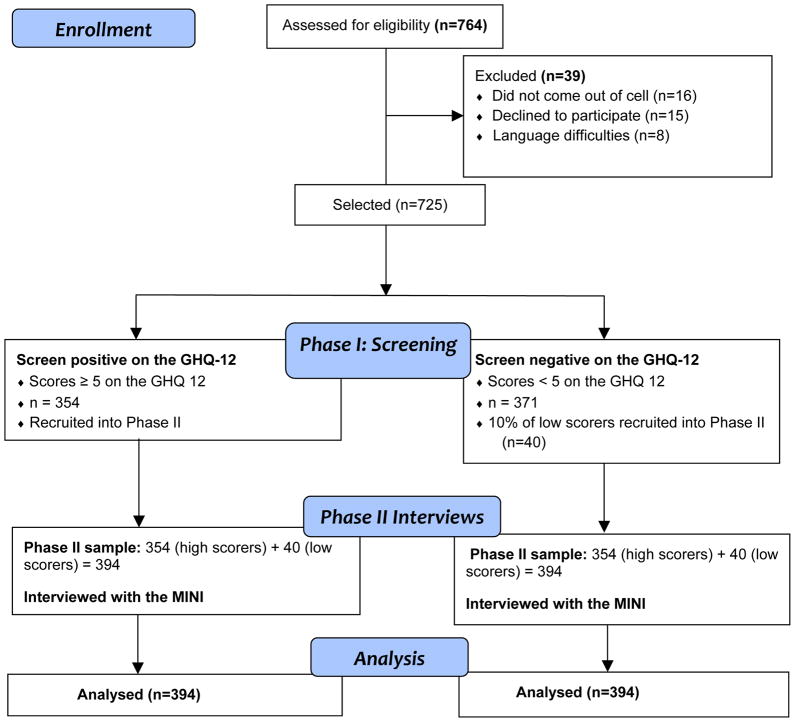

A cross-sectional multi-phase study was conducted at the Agodi Prisons, Ibadan between December 2012 and February 2013. Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Ibadan and the University College Hospital’s Ethics and Research Board, and official permission was granted by the Controller of Prisons, Oyo State Command. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after discussions about the research aims and objectives, with explanations about the voluntary nature of participation and the confidentiality of their responses. They were additionally notified that the researchers could not be of any assistance whatsoever in securing any privileges within the prison or judicial systems. Conversely, they were also reassured that no one could put them into any trouble or difficulties, if they were to decline participation. The inclusion criteria were a). inmates awaiting trial and remanded at the Prisons b). aged 18 years or older and c). provided informed consent. Those who were acutely ill and those who could not speak passable English or Yoruba languages were excluded (See Figure 1). This was a subset of a larger prison mental health survey in Agodi Prisons, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Figure 1.

Consort flow chart summary of study participants

Study Procedure

In the first phase, a socio-demographic questionnaire and the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) - a short screening instrument for assessing probable psychological distress, were administered to all consenting awaiting trial inmates by trained research interviewers. The GHQ-12 had been previously validated [9] and extensively used in Nigeria, including among prison populations [3,4]. A total of 725 respondents were interviewed, out of an available figure of 764 awaiting trial inmates, representing a response rate of 95%. The interviews were conducted within the open yard but out of earshot of the prison officials, who had to keep an eye on proceedings for security reasons.

All the respondents with GHQ-12 scores ≥ 5 were recruited into the second phase, which consisted of an interview by mental health professionals (2 psychiatrists and a clinical psychologist), using a semi-structured diagnostic instrument, the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), version 6.0, which had also been previously adapted and used in this setting [10,11]. About 10% of low scorers on the GHQ – 12 were also recruited into the second phase (See Figure 1). The interviewers were blind to the initial screen scores on the GHQ-12, and they generated diagnosis about the presence or absence of a mental disorder in the respondents, using the MINI.

Analysis

The data generated was entered using Microsoft Excel version 7.0 and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16 (Illinois USA). Frequencies and proportions were reported as summary statistics for all variables. Additionally the age of respondents was summarized using the mean and standard deviation. A diagnosis of current neuropsychiatric disorder was determined based on responses to items on different sections of the MINI excluding suicidality. Association between the diagnosis of a neuropsychiatric disorder and variables (selected socio-demographic and prison-related) were tested using Chi square tests. The associations on Chi square tests which were significant at 20% level were entered into a multiple logistic regression model. The ENTER option of SPSS was used for variable selection where all variables are entered in one block. Adjusted odds ratios and 95% Confidence intervals were reported. The level of significance was set at 0.05, two-tailed.

Results

A total of 394 respondents participated in the study with a mean age of 31.1 years (SD = 8.7), with ages ranging from 18 – 70 years. The study population was predominantly male, with only 1.3% of the sample being female. There was an equal proportion (45%) of Christians and Muslims, while nearly half of the respondents (49.3%) had a minimum of secondary education. The mean duration of incarceration at Agodi was 1.1 years (SD = 1.47), with a range of 1 week to 10 years. Nearly half (48.3%) had no legal representation, while about 60.4% were convinced that their legal case was not making any progress in court. The commonest reasons adduced for the perceived lack of progress in court included lack of legal representation, frequent adjournments, no shows from the Investigating Police Officer (IPO), and witnesses not coming forward to testify. The majority of the awaiting trial inmates (63.3%) had only one set of clothes which they wore every day. Other demographic details along with prison related variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics and prison-related variables (n =394)

| Variable | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | ||

| 18–24 | 83 | 21.1 |

| 25–29 | 109 | 27.7 |

| 30–34 | 91 | 23.1 |

| 35+ | 111 | 28.2 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 389 | 98.7 |

| Female | 5 | 1.3 |

| Level of education | ||

| None | 39 | 9.9 |

| Primary | 161 | 40.9 |

| Secondary | 148 | 37.6 |

| Tertiary | 46 | 11.7 |

| Religion | ||

| Islam | 179 | 45.4 |

| Christianity | 214 | 45.2 |

| Traditional | 1 | 9.4 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 353 | 89.6 |

| Unemployed | 40 | 10.4 |

| Average monthly income | ||

| None | 58 | 14.7 |

| Less than 20000 | 132 | 33.5 |

| 20000 – 50000 | 118 | 29.9 |

| 50000+ | 86 | 21.8 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 163 | 41.4 |

| Married | 215 | 54.6 |

| Separated/divorced/late | 16 | 4.1 |

| Time spent in Agodi prison | ||

| Less than 6 months | 164 | 41.6 |

| 6–12ths | 73 | 18.5 |

| More than 1year | 157 | 39.8 |

| Position in cell | ||

| Yes | 65 | 16.5 |

| No | 329 | 83.5 |

| Number of previous arrests | ||

| None | 330 | 83.8 |

| 1 | 42 | 10.7 |

| 2+ | 22 | 5.6 |

| Frequency of visitors from outside prison | ||

| Daily/Weekly | 102 | 25.9 |

| Less frequent than weekly | 169 | 42.9 |

| Never | 123 | 31.2 |

The overall prevalence of mental illness was 56.6% with the commonest conditions being depression (20.8%), alcohol dependence (20.6%), substance dependence (20.1%), suicidality (19.8%) and antisocial personality disorder (18%). The comprehensive list of disorders and their frequencies is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Prevalence of neuropsychiatric disorders among the awaiting trial inmates

| Diagnosis | Frequency | % (n=394) |

|---|---|---|

| Depression | 82 | 20.8 |

| Alcohol dependence | 81 | 20.6 |

| Substance dependence | 79 | 20.1 |

| Suicidality | 78 | 19.8 |

| Antisocial PD | 71 | 18.0 |

| Alcohol abuse | 41 | 10.4 |

| Panic (total) | 33 | 8.3 |

| Current with agoraphobia | 21 | 5.3 |

| Panic without agoraphobia | 6 | 1.5 |

| Agoraphobia without panic | 6 | 1.5 |

| Social phobia (total) | 31 | 7.9 |

| Current, generalized | 22 | 5.6 |

| Current, not generalized | 9 | 2.3 |

| OCD | 22 | 5.6 |

| Medical/Organic | 19 | 4.8 |

| PTSD | 13 | 3.3 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 11 | 2.8 |

| Psychosis | 4 | 1.1 |

| Anorexia | 0 | 0.0 |

| Bulimia | 0 | 0.0 |

| Overall prevalence of mental illness | 223 | 56.6 |

The association between diagnosis of any neuropsychiatric condition and selected socio-demographic and prison-related variables are shown in Table 3. Only frequency of visits from outside the prison was significantly associated with diagnosis of a neuropsychiatric condition. About 43% of those reporting daily or weekly visits compared to over 60% of those visited less frequently had a neuropsychiatric condition. After adjusting for position in cell and number of previous arrests, there was a significantly higher odds of a neuropsychiatric diagnosis among those visited less often (Table 4).

Table 3.

Association between diagnosis of mental illness and variables

| Variable | % with depression | N | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | |||

| 18–24 | 56.6 | 83 | 0.722 |

| 25–29 | 58.7 | 109 | |

| 30–34 | 59.3 | 91 | |

| 35+ | 52.3 | 111 | |

| Level of education | |||

| None | 61.5 | 39 | 0.818 |

| Primary | 55.3 | 161 | |

| Secondary | 55.4 | 148 | |

| Tertiary | 60.9 | 46 | |

| Religion | |||

| Islam | 54.7 | 179 | 0.465 |

| Christianity | 58.4 | 214 | |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 57.2 | 353 | 0.463 |

| Unemployed | 51.2 | 41 | |

| Average monthly income | |||

| None | 53.4 | 58 | 0.421 |

| Less than 20000 | 53.0 | 132 | |

| 20000 – 50000 | 56.8 | 118 | |

| 50000+ | 64.0 | 86 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 58.3 | 163 | 0.769 |

| Married | 55.8 | 215 | |

| Separated/divorce/late | 50.0 | 16 | |

| Time spent in Agodi prison | |||

| Less than 6 months | 54.9 | 164 | 0.331 |

| 6–12ths | 64.4 | 73 | |

| More than 1 year | 54.8 | 157 | |

| Position in cell | |||

| Yes | 64.6 | 65 | 0.154 |

| No | 55.0 | 329 | |

| Number of previous arrests | |||

| None | 54.8 | 330 | 0.112 |

| 1 | 59.5 | 42 | |

| 2+ | 77.3 | 22 | |

| Frequency of visits from outside the prison | |||

| Daily/Weekly | 43.1 | 102 | 0.006 |

| Less frequent than weekly | 60.9 | 169 | |

| Never | 61.8 | 123 | |

Table 4.

Odds ratios and confidence intervals of the regression analysis

| Variable | Odds ratio (OR) | 95% CI OR | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Position in cell | |||

| Yes | |||

| No(ref) | 1.38 | 0.78 – 2.43 | 0.264 |

| Previous arrests | |||

| Yes, once | 1.21 | 0.62 – 2.35 | 0.582 |

| Yes twice or more | 2.50 | 0.89 – 7.01 | 0.081 |

| No (ref) | 1 | ||

| Frequency of visits from outside the prison | |||

| Daily/Weekly (ref) | 1 | ||

| Less frequent than weekly | 1.93 | 1.16 – 3.20 | 0.011 |

| Never | 2.05 | 1.20 – 3.52 | 0.009 |

Discussion

The composition of the prison population as at the time of the study, was such that awaiting trial inmates constituted nine in every ten (91.6%) of the total inmate lock-up. This further underlined the salience of this study to shed light on their mental health problems and to compare with previous results obtained from convict populations.

The demographic details of the respondents in this study presented some expected and some unexpected results. While it was not surprising that they were predominantly male and young, with a mean age of 31.1 (SD = 8.7), it was not anticipated that they will have reasonably high levels of education, with only about 10% not having had any formal schooling. Furthermore, nearly nine out of every ten respondents were engaged in some sort of employment or the other prior to their incarceration; while slightly more than half of the respondents earned a reasonable monthly income (greater than N20,000) prior to their arrest.

About four in ten of the respondents had spent greater than one year in prison awaiting trial, and nearly half of them (48.3%) had no legal representation. This finding is supported by previous reports on the Nigerian Prison system and the slow wheels of the Justice system, which is often compounded by a lack of means to retain legal services for adequate representation [8]. Furthermore, the inmates were generally pessimistic about the legal processes as 6 out of 10 respondents were convinced that they were not making any progress in court.

The living conditions of the awaiting trial inmates was far from ideal as six out of ten respondents possessed only one set of clothes, which was mostly torn and in various forms of disrepair. Most of the inmates depended on the goodwill and donations of clothes by visitors to allow them enjoy a change of clothes, since they were not entitled to the formal prison uniforms reserved for convicted inmates.

The prevalence of neuropsychiatric disorders in this population was 56.6%, which was quite close to the 57% prevalence found among the convict population of the Agodi prisons in the larger survey of mental health conditions and wellbeing. While this prevalence rate is higher than the 34% reported by Agbahowe et al., from Benin City [3], it however agrees with the more recent findings from Jos prisons where Armiyau et al., reported a prevalence rate of 57% among the convict population [4]. Thus the findings from this study may suggest that there is no significant difference in the prevalence of mental health problems among the awaiting trial inmates as compared to the convict population.

The commonest disorders among the awaiting trial inmates in this study agrees with previous reports of prison studies in Nigeria [3,4]. The similarities include the observation that depression and substance use disorders were the most common disorders in all three studies. Psychosis (1.1%) and mania (1.1%) were both low in this study but were similarly low, at 2% for psychosis in Benin [3] and 1.2% and 0.6% for psychosis and mania respectively, from the Jos study [4].

Salient observations from this study includes the relatively high rate of suicidality [19.8%] reported by the respondents. While the majority of these respondents had scores indicative of only a low risk for suicidality, its presence in itself, is perhaps a reflection of the feelings of desperation and a bleak outlook towards life in their current circumstances.

Furthermore, the prevalence of antisocial personality disorder was quite high at 18%, but this is not altogether surprising. Previous studies have documented that antisocial personality disorder is one of the commonest personality disorder within prison populations [12,13]. It was also not surprising to note that none of the respondents were diagnosed with an eating disorder, specifically anorexia and bulimia.

The frequency of visitors from outside the prison was the only significantly associated variable with the presence of a neuropsychiatric disorder. Those inmates who were visited less frequently were twice more likely to have a neuropsychiatric disorder as compared to their peers who were visited more frequently (daily or weekly). This finding may be related to the fact that frequent visits from outside the prison system is not only a reflection of care and concern but it also possibly offers a beacon of hope to cling unto, that there will be light at the end of the tunnel.

Conclusion

This study revealed a high prevalence of neuropsychiatric disorders which does not however appear to be significantly different from that of convict populations. However, the awaiting trial inmates had high levels of suicidality, and receiving fewer visitors appear to increase the risk of developing neuropsychiatric conditions. Additional research is required to provide more insight into the factors that may be protective against development of neuropsychiatric disorders within this target population, such as retaining hope and levels of self-esteem.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Prison authorities and all the inmates who participated in this study. We are also grateful to Dr Adeyemi and all the Prison Medical Personnel at Agodi Prisons and Dr Olabamiji Badru, Dr Odunleye, Dr Oladele and Mr Dotun for their co-operation and support.

This study was supported by the Medical Education Partnership Initiative in Nigeria (MEPIN) project funded by Fogarty International Center, the Office of AIDS Research, and the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institute of Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and the Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator under Award Number R24TW008878.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding organizations.

References

- 1.Hassan L, Birmingham L, Harty MA, et al. Prospective cohort study of mental health during imprisonment. BJP. 2011;198:37–42. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naidoo S, Mkize DL. Prevalence of mental disorders in a prison population in Durban, South Africa. Afr J Psychiatry. 2012;15:30–35. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v15i1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agbahowe SA, Ohaeri JU, Ogunlesi AO, Osahon R. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among convicted inmates in a Nigerian prison community. East Afr Med J. 1998;75:19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armiya’u A, Obembe A, Audu M, Afolaranmi T. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among inmates in Jos maximum security prison. Open Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;3:12–17. doi: 10.4236/ojpsych.2013.31003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gureje O, Lasebikan VO, Kola L, Makanjuola VA. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of mental disorders in the Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:465–71. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.5.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orakwe IW. Comparative study of prisoners feeding in selected countries of the world; Nigeria and Britain in focus. 2008 Retrieved online from the Nigerian Prisons Service website: www.Prisons.gov.ng.

- 7.Nigerian Prisons Service. Prison Statistics. 2011 Available from the Nigerian Prisons Service website: www.Prisons.gov.ng.

- 8.Amnesty International. Nigeria: Human Rights Agenda 2011–2015 Report. AFR 44/014/2011. 2011:6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gureje O, Obikoya B. The GHQ-12 as a screening tool in a primary care setting. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1990;25:276–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00788650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Aloba OO, Mapayi BM, Ibigbami OI, Adewumi TA. Alcohol use disorders among Nigerian University students: Prevalence and Sociodemographic correlates. Nigerian Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;5(1):5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogebe O, Abdulmalik J, Bello-Mojeed MA, Holder N, Jones HA, Ogun OO, Omigbodun O. A comparison of the prevalence of premenstrual dysphoric disorder and comorbidities among adolescents in the United States of America and Nigeria. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24(6):397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slade K, Forrester A. Measuring IPDE-SQ personality disorder prevalence in presentence and early-stage prison populations, with sub-type estimates. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2013;36(3–4):207–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayirolimeethal A, Ragesh G, Ramanujam JM, George B. Psychiatric morbidity among prisoners. Indian J Psychiatry. 2014;56(2):150–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.130495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]